It starts with the dragging off of a lamb. It ends with bearmadillos.

Introducing ‘Unexpected Isle of Wight Air-Filled Hunter’, a New English Theropod Dinosaur

As a regular reader here, you might be familiar with the idea that we’re currently in a Golden Age of dinosaur discovery. More fossil dinosaurs are being discovered, monthly and annually, than at any other point in history, and numerous locations worldwide – even those considered well explored and well understood scientifically – continue to yield new species. Yes, new dinosaurs are found in countries like Malawi, Ecuador and Tanzania, and in Antarctica, but new dinosaurs are also found in the USA, France, Spain and the UK. This week sees the publication of yet another new dinosaur from England. I’m writing about it because I’m one of its describers.

RIP Brian Franczak (1955-2020)

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos

If you’re a long-time reader of TetZoo, you’ll know that I’ve often examined and discussed the backstories to famous monster photos. And if you follow me on Twitter (I’m @TetZoo), you’ll know that I’ve lately been posting extremely long threads wherein I do likewise. It’s fun and results in lots of interaction. Today, I’m going to conduct an experiment and publish a monster-themed article here at the blog AND a threaded version of the same text at Twitter.

A Love Letter to the Common Frog

Why the World Has to Ignore David Peters and ReptileEvolution.com

The Dodo in Life

You’re already highly familiar with the Dodo Raphus cucullatus, and images of what this animal looked like in life are present in a vast number of books, popular sources and museum displays. What might not be so familiar to you is that the Dodo’s life appearance has been the subject of long-standing debate, that many familiar ideas about its appearance are very likely wrong, and that – even today – we’re uncertain about several details.

Dougal Dixon’s After Man, the Initial Pitch Document

There can’t be many visitors here who are unaware of Dougal Dixon and his 1981 book After Man (Dixon 1981), the work which effectively started the entire Speculative Zoology (or SpecZoo) movement.

The Shrews of the World

Cloudrunners and Other Cloud Rats of the Philippines

I’ve surely said on several occasions over the years that I’ve never written enough about rodents here at TetZoo. But, then, you could write about nothing BUT rodents and still not write about them enough… there are just so many of them, both in terms of numbers of species and individuals. Whatever, I’ve opted today to write about cloudrunners and other cloud rats, a group of luxuriantly furred, large, striking members of Muridae – the rat and mouse family – endemic to the Philippines.

Did Mesozoic Mammals Give Birth to Live Babies or Did They Lay Eggs?

If you know anything about mammals, you’ll know that crown-mammals – modern mammals – fall into three main groups: the viviparous marsupials and viviparous placentals (united together as therians), and the egg-laying monotremes. The fact that monotremes lay eggs is familiar to us today, but of course it was a huge surprise when first discovered. There’s a whole story there which I won’t be recounting here.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 8 (THE LAST PART)

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 7

Welcome to part – oh my god – seven in this seemingly eternal series.

Like me, I’m sure you want it to end so I can get back to writing about the innumerable other things on the list. Yes, we’re here, once again, for another instalment in the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series. If you’re new to the whole thing, go back to Part 1 and see what this is all about; if you want to see all previous parts in the series go to the bottom of the article for the links (or use the sidebar). In the most recent articles, we looked at two assumptions inherent to the TMDD contention: that sauropod populations were similar in structure to modern megamammal populations, and that sauropods and other big dinosaurs were similar to Holocene megamammals in ecology and distribution. Here, we look at a third assumption, and it’s one that just won’t die.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 6

Oh wow, we’re at Part 6 in the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series already. You’ll need to have seen at least some of the previous articles to make sense of this one: you can either follow the links below, or click through the links in the sidebar. In Part 5 we looked at the first of a series of assumptions made by those who’ve advocated the TMMD contention; namely, that Late Jurassic sauropods had a population structure similar to that of megamammals. In this article, we look at a second assumption…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 5

If you’ve been visiting TetZoo over recent weeks, you’ll know why we’re here. Yes, we’re here to continue with the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series, in which I argue that it’s wrong to argue – that is, on principle, rather on detailed evaluation of the evidence – that the world famous Late Jurassic Morrison Formation contains too many sauropods. In the previous four parts of this series we introduced the DMDD contention, we looked at the fact that Paleogene mammals are not especially relevant to the TMDD contention, and then at the fact that modern giraffes are not especially relevant to the TMDD contention either.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 4

In the previous articles in this series (see part 1 here, part 2 here and part 3 here) we looked at the ‘too many damn dinosaurs’ (TMDD) contention, this being the claim that the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation simply has too many sauropod dinosaurs. You’ll need to check those previous articles out before reading this one. The previous parts of the series introduce the TMDD contention and then discuss whether arguments made about Paleogene fossil mammals and modern giraffes are relevant. Here, we move on to something else.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 3

Welcome to the third part in this lengthy series of articles, all of which are devoted to the argument that those Mesozoic faunas inhabited by multiple sauropod taxa – in particular those of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation – have too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!). You need to have read parts 1 and 2 for this to make sense. Those articles set up the TMDD contention, and then showed why arguments relating sauropod diversity to Paleogene mammal diversity are erroneous. In this article, we look at another mammal-based argument.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 2

A few authors would have it that there are too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!): that the rich sauropod assemblage of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the continental western interior of the USA simply contains too many species, and that we need to wield the synonymy hammer and whack them down to some lower number. In this article and those that follow it, I’m going to argue that this view is naïve and misguided. You’ll need to have read Part 1 – the introduction – to make sense of what follows here. Ok, to business…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 1

Professor Jenny Clack, 1947-2020

Within recent decades, four specific areas of palaeontological discovery and reinterpretation have succeeding in capturing mainstream attention: the feathering of dinosaurs, the evolution of hominins, the early history of whales, and the early evolution, anatomy and biology of the earliest tetrapods. And it’s the last of those subjects we’re focusing on here. It’s a subject which has seen regular airing in top-tier journals, science magazines and TV documentaries, and one which has undergone a major and exciting revolution since the 1980s.

Caption: at left, Professor Jenny Clack, in the field at Burnmouth in the Scottish Borders. At right: in 2017, Jenny and her husband Rob got to fly in a Spitfire. Images: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

One person above all others has been responsible for leading research in this field and has made numerous ground-breaking discoveries herself, both in the field and laboratory. I am of course referring to Professor Jenny Clack of the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge, an excellent and highly respected scientist whose technical papers are authoritative, ground-breaking and of the highest standard. Her publication list is formidable. Alas, I regret to write that I’m here for sad reasons, since Jenny died on the morning of 26th March 2020 following a five-year struggle with cancer. While – for my shame – I haven’t written about early tetrapod evolution here at TetZoo before, nor about Jenny’s research specifically, both are areas I’ve avidly followed, and I want to share some brief thoughts here.

Caption: a selection of Clack publications in the TetZoo library. Image: Darren Naish.

Prior to Jenny’s work, the consensus view on the oldest tetrapods – in particular Ichthyostega from the Devonian of Greenland – is that these were ‘terrestrialised’, vaguely salamander-like quadrupeds, well able to walk on land by planting all four feet on the substrate. This view, entrenched in textbooks and the popular literature, mostly owed itself to the work of Swedish palaeontologist Erik Jarvik whose work on Ichthyostega, while initiated in the 1950s, took some decades to appear, finally being published in 1996. Jarvik’s work has its own long and curious backstory (Ries 2007) – which I can’t cover here – and it certainly wasn’t missed by some of us that the conclusions of his supposedly definitive monograph were being called into doubt just weeks after its appearance (Norman 1996).

Caption: Jenny Clack (and Professor Robert Insall) at the Ballagan Formation type locality, near Glasgow. Image: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

Tantalising remains of an Ichthyostega contemporary – the smaller Acanthostega – were discovered in East Greenland on a Cambridge University expedition of 1970 (and were languishing, unrecognised, in the drawers of the university’s earth sciences department prior to Jenny’s interest). These indicated that, with luck, more early tetrapod finds might be discovered in the same region. After making special arrangements with Danish scientists – and with Jarvik, who the Danes wanted to remain on good terms with – Jenny visited Greenland in 1987; she was accompanied by colleagues from Copenhagen, her husband Rob and her then PhD student Per Ahlberg (Clack 1988). They were remarkably successful, retrieving multiple good specimens, and continued to be so on later trips to the same region.

Caption: in more recent years, it’s become obvious that Ichthyostega - the classic ‘early tetrapod’ - was not just a formidable, toothy predator, but an unusual, specialised animal with paddle-like hindlimbs, a proportionally short tail and a regionalised vertebral column. Image: Ahlberg et al. (2005).

Was Jarvik right about these animals? Not really, no. The discovery of numerous aquatic specialisations in Ichthyostega and the smaller Acanthostega – published by Mike Coates and Jenny during the early 1990s (Coates & Clack 1990, 1991) – was a huge surprise. Tetrapods didn’t start their history as land-walking animals with pentadactyl hands and feet, as Jarvik (and just about everyone else) had thought, but were aquatic and polydactyl, with 8 fingers and 7 toes (or thereabouts)! Later work showed that Ichthyostega had an unusual ear perhaps specialised for aquatic hearing (Clack et al. 2003) and a remarkable regionalised vertebral column and other peculiarities (Ahlberg et al. 2005) suggesting that, when on land, it might have moved in mudskipper-like fashion (Ahlberg et al. 2005, Pierce et al. 2012, 2013).

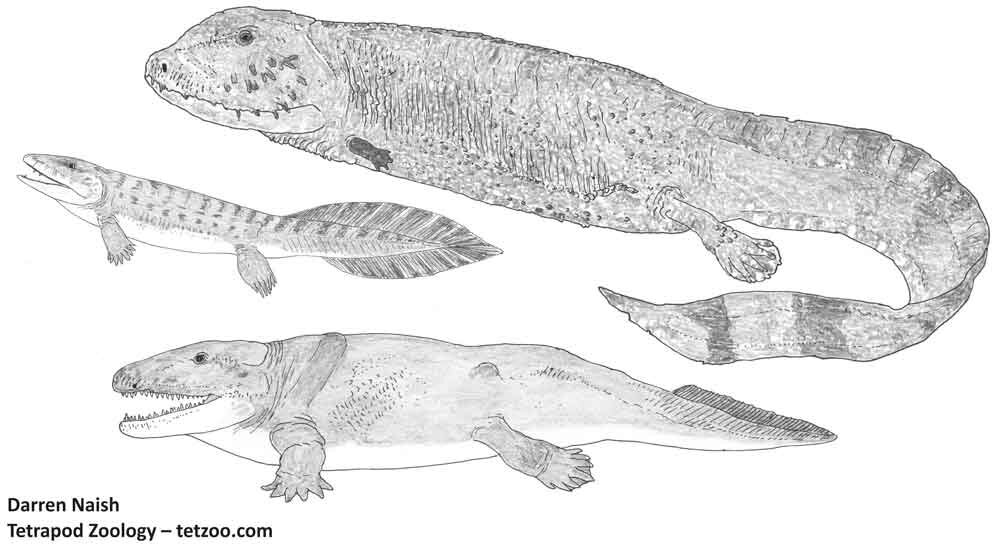

Caption: life reconstructions of three early tetrapods worked on by Clack: the big Crassigyrinus, the small, aquatic Acanthostega, and the big (c 1 m long) Ichthyostega. These images are among tens of archaic tetrapods reconstructed for my in-prep textbook. I’ve learnt recently that the Crassigyrinus will soon need revising. Image: Darren Naish.

Jenny’s work wasn’t limited to this fundamental reinterpretation of the earliest tetrapods, but also involved taxa from throughout the Devonian and Carboniferous. She revised knowledge of the remarkable aquatic Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus (Clack 1998a), described the new species Eucritta melanolimnetes (Clack 1998b), Pederpes finneyae (Clack 2002a, Clack & Finney 2005), Kyrinion martilli (Clack 2003) and others, reported entire new faunal assemblages (Clack et al. 2016) and published key interpretations of such groups as embolomeres (Clack 1987, Clack & Holmes 1988), chroniosuchians (Clack & Klembara 2009, Klembara et al. 2010) and microsaurs (Clack 2011). This extensive, substantial experience made her the right person to publish an authoritative and comprehensive book on Devonian and Carboniferous tetrapods: Gaining Ground: The Origin and Evolution of Tetrapods appeared in 2002 (Clack 2002). It went to second edition in 2012. It’s the best guide to early tetrapod evolution and fills a much-needed gap in the semi-technical literature, and I strongly recommend it to those interested in the subject.

Caption: covers of the first and second editions of Clack’s Gaining Ground. The cover images are, respectively, by Jenny Clack and Julia Molnar. The Clack image shows two individuals engaging in courtship: the green hump at the back left is the body of a second animal.

I never had the privilege of working with Jenny or of accompanying her in the field, but I did have reason to speak to her on several occasions, and to correspond with her. She was friendly and generous with her time and went to trouble to provide me with information and illustrations on an occasion when email wasn’t doing its job. It’s also obvious that she had a sense of humour. Of those new species listed above, Eucritta melanolimnetes translates roughly as ‘creature from the black lagoon’. Some – probably all – of the Ichthyostega and Acanthostega specimens she discovered in Greenland had nicknames: I’m pretty sure I recall seeing that one of them was called Grace Jones. Those who knew her so much better confirm that she was excellent fun, a great leader in the field, and a brilliant mentor.

Caption: several of the archaic Devonian tetrapods study by Clack and her colleagues are excellent, 3D and with very detailed preservation. This image shows an Acanthostega gunnari cast at Musee De L'Histoire Naturelle, Brussels. Image: Ghedoghedo. CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Jenny began her scientific career during the early 1970s and received her PhD at the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne in 1984 under Alec Panchen. Panchen initially offered her a PhD following anatomical discoveries she made while preparing the notoriously difficult holotype specimen of the Carboniferous embolomere Pholiderpeton, initially described by Thomas Huxley in 1869. She joined the University of Cambridge in 1981 and for more than ten years was Assistant Curator at the University’s Museum of Zoology, later being promoted to Senior Assistant Curator and then Curator. She supervised a number of people who went on to become well known in vertebrate palaeontology and evolutionary biology, among them Mike Lee (whose PhD was specifically on pareiasaurs), sauropod expert Paul Upchurch, and actinopterygian fish worker Matt Friedman.

Caption: life-sized models of Ichthyostega and Acanthostega have been made a few times. Here’s the Acanthostega on show at the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge. I’ve photographed this model several times but none of my photos are that good - I stole this image from Christian Kammerer (source).

Jenny retired in 2015. As you might expect give her scientific achievements, she was highly decorated, holding several palaeontological medals, additional, honorary doctorates and other awards too. Such was mainstream interest in her work and ideas that a 2012 episode of the BBC series Beautiful Minds was devoted to her (it’s viewable here on youtube); among other interesting things, it reveals that she was inspired during her childhood years by newts and freshwater fishes, and that it was learning about Mary Anning which encouraged her to pursue palaeontology. She liked motorbikes and cats, and some of the documentaries that focus on her work show her riding around on her motorbike.

Caption: the Tournaisian rocks of Burnmouth, north of Berwick-upon-Tweed, have, within recent decades, proved an important new locality for tetrapods. As a consequence, Jenny and colleagues set up the TW:eed Project, the acronym standing for Tetrapod World: Early Evolution and Diversity. Jenny (in the green top) stands close to the middle. Image: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

My text here only touches on a few aspects of her achievements, life and technical contributions, and I know that much else could be said. I’m very saddened to hear of her passing, very much regarded her as an excellent scientist who published exciting research, and I’ll miss her as a regular attendee of palaeontological meetings. My sincere condolences to her husband Rob, and to those others who knew and loved her.

Some of the text here is adapted from my in-prep giant textbook on the vertebrate fossil record.

The University of Cambridge website on Professor Clack is here

An excellent website on Professor Clack’s research and expeditions is here

Refs - -

Ahlberg, P. E., Clack, J. A. & Blom, H. 2005. The axial skeleton of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 437, 137-140.

Clack, J. A. 1987. Two new specimens of Anthracosaurus (Amphibia: Anthracosauria) from the Northumberland coal measure. Palaeontology 30, 15-26.

Clack, J. A. 1988. Pioneers of the land in East Greenland. Geology Today 4 (6), 192-194.

Clack, J. A. 1998a. The Scottish Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus scoticus (Lydekker) – cranial anatomy and relationships. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences 88, 127-142.

Clack, J. A. 1998b. A new Early Carboniferous tetrapod with a mélange of crown-group characters. Nature 394, 66-69.

Clack, J. A. 2002a. An early tetrapod from 'Romer's Gap'. Nature 418, 72-76.

Clack, J. A. 2003. A new baphetid (stem tetrapod) from the Upper Carbinoferous of Tyne and Wear, U.K., and the evolution of the tetrapod occiput. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40, 483-498.

Clack, J. A. 2011. A new microsaur from the Early Carboniferous (Viséan) of East Kirkton, Scotland, showing soft tissue evidence. Special Papers in Palaeontology 86, 45-55.

Clack, J. A., Ahlberg, P. E., Finney, S. M., Dominguez Alonso, P., Robinson, J. & Ketcham, R. A. 2003. A uniquely specialized ear in a very early tetrapod. Nature 425, 65-69.

Clack, J. A., Bennett, C. E., Carpenter, D. K., Davies, S. J., Fraser, N. C., Kearsey, T. I., Marshall, J. E. A., Millward, D., Otoo, B. K. A., Reeves, E. J., Ross, A. J., Ruta, M., Smithson, K. Z., Smithson, T. R. & Walsh, S. A. 2016. Phylogenetic and environmental context of a Tournaisian tetrapod fauna. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1: 0002.

Clack, J. A. & Finney, S. M. 2005. Pederpes finneyae, an articulated tetrapod from the Tournaisian of western Scotland. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 2, 311-346.

Clack, J. A. & Holmes, R. 1988. The braincase of the anthracosaur Archeria crassidisca with comments on the interrelationships of primitive tetrapods. Palaeontology 31, 85-107.

Clack, J. A. & Klembara, J. 2009. An articulated specimen of Chroniosaurus dongusensis and the morphology and relationships of the chroniosuchids. Special Papers in Palaeontology 81, 15-42.

Coates, M. I. & Clack, J. A. 1990. Polydactyly in the earliest known tetrapod limbs. Nature 347, 66-69.

Coates, M. I. & Clack, J. A. 1991. Fish-like gills and breathing in the earliest known tetrapod. Nature 352, 234-236.

Klembara, J., Clack, J. A. & Čerňanský, A. 2010. The anatomy of palate of Chroniosuchus dongusensis (Chroniosuchia, Chroniosuchidae) from the Upper Permian of Russia. Palaeontology 53, 1147-1153.

Norman, D. 1996. [Review of] The Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Palaeontological Newsletter 31, 13-15.

Pierce, S. E., Ahlberg, P. E., Hutchinson, J. R., Molnar, J. L., Sanchez, S., Tafforeau, P. & Clack, J. A. 2013. Vertebral architecture in the earliest stem tetrapods. Nature 494, 226-229.

Pierce, S. E., Clack, J. A. & Hutchinson, J. R. 2012. Three-dimensional limb joint mobility in the early tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 486, 523-526.

Ries, C. J. 2007. Inventing ‘the four-legged fish’. The palaeontology, politics and popular interest of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega, 1931-1955. Ideas in History 2, 37-78.