Another belated book review! Yes, let’s look at…

I think it’s fair to say that virtually everyone interested in animals (tetrapods, anyway) has a heavy interest in Pleistocene megafauna. We grow up with some sort of familiarity with these creatures – sabretooth cats, mammoths, giant sloths, ‘Irish elk’, Neanderthals – and, worldwide, are mostly aware of the fact that they, and their ecological impact, have only recently disappeared.

With this in mind, Dr Ross Barnett’s 2019 The Missing Lynx: the Past and Future of Britain’s Lost Mammals is a book for us all. Don’t be put off at all by the fact that it’s written very much from a British perspective (indeed, a north-of-Britain perspective, given Barnett’s Scottishness); Barnett is an unashamed and proud Pleistocene advocate, and his advocacy is relevant to Pleistocene studies worldwide, not the British Isles alone. If we avoid as much as we can the now hideous political and socioeconomic leanings of the UK, the British Isles are – I contend – really interesting and important from a phylogeographic and zoological perspective: these islands are, after all, a large, maritime archipelago sited on the north-western fringes of three great, connected continents that stretch far to the east and south. This ‘fringe’ position does make the region dangerously irrelevant to the main narrative for many things (insert appropriate Brexit metaphor here), yet inherently and powerfully relevant to others: fringes are where living things are first to disappear, or last to disappear; where the most specialised variants live, or where the most generalised variants live; and where the most sedentary populations are, or where the most mobile populations sometimes occur. It’s complicated, evidently.

Caption: evidence of the former presence of Brown bear Ursus arctos is widespead across the UK, including in place names and also fossil and zooarchaeological remains (O’Regan 2018). This is the skull of the Badger Hole bear: Badger Hole is a cave close to the famous Wookey Hole in Somerset. Another cave called the Hyena Den is nearby. Image: Darren Naish.

And given that the British Isles were home to Cave hyenas, the sabretooth Homotherium, Cave lions (yes, Barnett uses this term with preference to Steppe lion), Woolly mammoths, Woolly rhinos, bison and aurochs, bears, lynxes and wolves, the stories of these British populations are very much part of a larger, Eurasian or Eurasian-African whole.

Caption: semi-captive European bison or Wisent Bison bonasus, observed in Romania. You’ll note that they have a rather more cow-ish look than American bison. There are reasons for this (a long history of hybridisation). Image: Darren Naish.

Ross Barnett is a qualified palaeogenomicist who earned his PhD at the University of Oxford. He’s well known for his work on cat genetics and phylogeny, and for studies on bears, voles, chickens, yetis (Edwards & Barnett 2014) and more. His crowning achievement, no doubt, was his 2019 talk at TetZooCon.

Barnett goes through each of the animals listed above in turn, chapter by chapter, working his way toward the present and ending with Eurasian beaver. There’s something inevitably melancholy about the fact that the book charts the domino-like disappearance of the biggest and most charismatic animals one after another, until only beavers are left. Ok, the very last chapter covers rewilding, ideas about genetic resurrection and the return to Europe of wolves, lynxes, beavers and others, so there is at least a bit of an emotional uptick at the end.

Caption: seriously, what a good looking book.

One thing I want to note is that the book is a tremendously satisfying physical object: perfect in terms of size, weight, colour balance, design and even feel. The text is beautifully arranged and spaced on the page and the semi-abstract depictions of the animals – featured at the start of each chapter as well as on the cover – are a joy to look at. People don’t talk about the physical characteristics of books often enough, despite the fact that they’re crucially important and involve a lot of work, thought and planning. I’m in love with books as physical objects (an obsession detrimental to my welfare: we’re all aware of the space and costs involved in storing and moving books), and feel that physical books are approximately seventy million time more memorable, more tangible than – ugh – ebooks.

Caption: the surprisingly recent disappearance of the Northern or Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx from the UK requires that we really should be - and are - discussing its potential reintroduction. Image: Darren Naish.

On the text, Barnett is a sound writer, his prose flowing and being marked throughout by his voice and cheeky sense of humour. I laughed quite a lot while reading. Extra points for the Star Wars references, Ross. Each chapter starts with a literary quote or (in a few cases) a poem. I dislike poetry, I think mostly because poems are, not merely pretentious and bilious, but often written as if you’re supposed to perceive, instantly and instinctively, the tempo and arrangement of the nonsense scatter of the words. Thankfully, Barnett doesn’t feature too much of it.

As someone obsessively interested in animals, I don’t find the mechanics or mechanisms of extinction especially interesting, and I can’t be the only one who’s gleefully obtained a ‘Pleistocene megafauna’ book only to find that it’s all about extinction and not animals at all. Don’t get me wrong; you can’t talk about the Pleistocene megafauna without covering extinction at some point, I know. But with this in mind, I like that Barnett gets the extinction discussion out of the way at the start of the book (Chapter 1). Extinction is the least interesting thing about extinct animals; there, I said it.

On contentious or disputed areas (like the cause of the Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions), I universally found Barnett’s position to be one I find maximally palatable, or one I was relieved to see aired since it explains my own confusion. An example of the first of those areas is that he’s a supporter of the idea that human action was (and still is) the primary cause of megafaunal extinction. I’m not a Pleistocene specialist, but I’ve essentially always been an advocate of this view too and am troubled by suggestions that non-human causes might have been to blame. Barnett’s discussions of shifting baseline syndrome, of our understanding and definition of ‘natural’ habitats (a subject painfully important for the UK) and of the debate over use of the term ‘Anthropocene’ were also proverbial music to my ears.

Caption: the Wolf Canis lupus is another animal whose metaphorical footprint is firmly stamped into the fabric of British culture and geography. It’s tragic but oh so telling that we extirpated this quintessential symbol of wild places. The object at right is the famous Ardross wolf stone, a stunning piece of 6th or 7th century Pictish art discovered in 1890 in Ardross, Ross-shire (northern Scotland), and on show today at Inverness Museum. Images: Darren Naish; Canmore (original here).

An example of the second of the aforementioned areas (where I was relieved to see his position aired) concerns his comments on dog domestication. I’ve never written much about dog domestication (and what I have written is confused and sometimes contradictory), partly because I struggle to recall or discover anything approaching a consistent or tidy narrative emerging from the vast number of works on this very complex subject (e.g., Savolainen et al. 2002, Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005, vonHoldt et al. 2010, Larson et al. 2012, Freedman et al. 2014). It turns out that it’s not just me: “Despite all the research … I’m not convinced that anything more than tentative conclusions have been reached” (Barnett 2019, p. 250). Phew.

The book is so on-the-ball in terms of technical accuracy that you might struggle to find technical problems or mistakes, should you go looking for them. In his discussion of the great deer Megaloceros, I felt that the text was – just once or twice – a little provincial in making out that everything we know about Megaloceros relates specifically to the famous ‘Irish elk’ M. giganteus. Unless I missed it (apologies if so), there’s no reference to the fact that M. giganteus is actually only one of a list of megacerine* species and genera. And is the term ‘Shelk’ really a neologism devised by Finnish palaeontologist Björn Kurtén (p. 139)? I don’t think so. As discussed here at TetZoo before (a few times, albeit always in the comments), Shelk is an old term – famous for its appearance in the 12th century poem the Nibelungenlied – co-opted by palaeontologists (perhaps incorrectly) for Megaloceros.

* Yeah – the lineage that includes Megaloceros is termed Megacerini, not Megalocerini as it ‘should’ be. It’s tied to the fact that Megaloceros was, for a time, known as Megaceros.

Caption: Megaloceros giganteus is but one of a reasonable number of megacerine taxa (here shown - probably correctly, I think - to include Dama). This montage is from Geist (1999). At right: my slightly controversial effort to reconstruct M. giganteus in life, as discussed in this TetZoo article of 2018.

I have to comment on the fact that Barnett literally never wastes an opportunity to cast Victorian anatomist, zoologist and palaeontologist Richard Owen in a negative light. He does so in the Homotherium discussion on pages 63-64, again in the Megaloceros section (Owen is described as “ghastly” on p. 154), and again in the wolf section (p. 244). Look, there’s no way anyone could doubt that Owen was often a total shit when it came to his workplace politicking; this is well attested by his peers and demonstrated by more than one paper trail. What I’m uncomfortable with is the implication that we have to denounce him every single time he’s mentioned. Not only were some of the people whose opinions we’ve been swayed by (like dear, gentle, lovely, Christ-like Gideon Mantell) essentially no better if not worse (yes, be careful where you get your history from, it might be horridly biased and/or inaccurate), Owen was, actually, human, was not a total shit all of the time, and was in fact so absurdly accomplished, brilliant and experienced that we really should – on occasion – frame him as a scientist, not so much as a villain. I’m slightly echoing Kevin Padian here (Padian 1997).

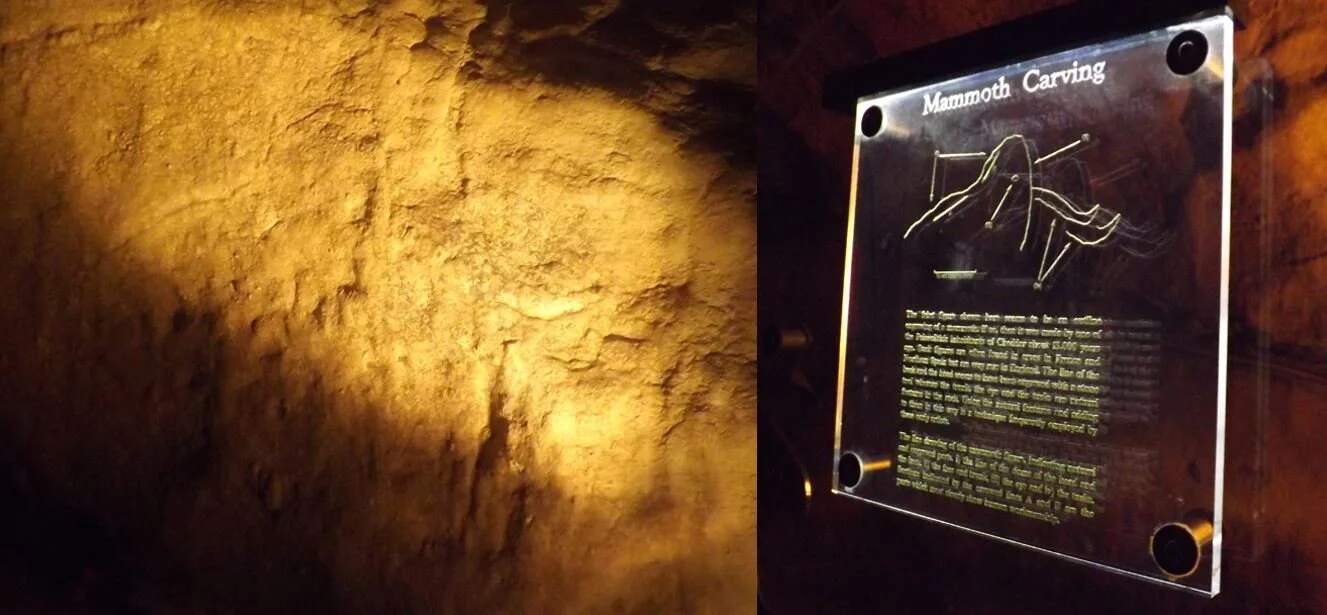

What might be a technical error is mention of the Creswell Crags bison (and an accompanying deer and other marks; p. 186) as the UK’s only piece of prehistoric rock art. That might not be true because there’s what’s supposed to be a depiction of a mammoth in Cheddar Cave (though I have to admit that it’s a dodgy-looking image). And I noticed but a single typo (‘husbrandry’; p. 173… despite appearances, I don’t think it’s a pun).

Caption: the somewhat underwhelming Cheddar Cave mammoth carving, just about visible at left if your imagination is good. The accompanying information board is at right. Images: Darren Naish.

In case it isn’t obvious by now, I really do like this book, and I recommend it very strongly. The Missing Lynx: the Past and Future of Britain’s Lost Mammals is fun to read and packed full of great stories, recountings, anecdotes and descriptions of Europe’s mostly lost megafauna and how we came to know of it; it’s ferociously up-to-date and provides great insight on recent discoveries and ongoing areas of research, all of which is wrapped up in a logically arranged narrative that has lessons about the present and future; and it’s compact, brilliantly designed and great to look at. Oh, and it’s very affordable too. If you’re at all interested in Pleistocene animals you should totally buy it. This has been a TetZoo endorsement :)

Barnett, R. 2019. The Missing Lynx: the Past and Future of Britain’s Lost Mammals. Bloomsbury Wildlife, London. pp. 352. ISBN 978-1-4729-5734-4. Hardback/paperback. Here from the publishers, here at amazon, here at amazon.co.uk

For previous TetZoo articles on Pleistocene and extinct Holocene megafauna, see…

The late survival of Homotherium confirmed, and the Piltdown cats, March 2006

The remarkable life appearance of the Woolly rhino, November 2013

Spots, Stripes and Spreading Hooves in the Horses of the Ice Age, February 2015

Five Famous Palaeolithic Rock Art Enigmas, July 2019

The Life Appearance of the Giant Deer Megaloceros, September 2019

Refs - -

Barnett, R. 2019. The Missing Lynx: the Past and Future of Britain’s Lost Mammals. Bloomsbury Wildlife, London.

Edwards, C. J. & Barnett, R. 2014. Himalayan 'yeti' DNA: polar bear or DNA degradation? A comment on 'Genetic analysis of hair samples attributed to yeti' by Sykes et al. (2014). Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 282, 20141712.

Freedman, A. H., Gronau, I., Schweizer, R. M., Ortega-Del Vecchyo, D., Han E., Silva, P. M., Galaverni, M., Fan, Z., Marx, P., Lorente-Galdos, B., Beale, H., Ramirez, O., Homozdiari, F., Alkan,C., Vil?, C., Squire, K., Geffen, E., Kusak, J., Boyko, A. R., Parker, H. G., Lee, C., Tadigotla, V., Siepel, A., Bustamante, C. D., Harkins,T. T., Nelson, S. F., Ostrander, E. A., Marques-Bonet,T., Wayne, R. K. & Novembre, J. 2014. Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs. PLoS Genetics 10 (1): e1004016.

Geist, V. 1999. Deer of the World. Swan Hill Press, Shrewsbury.

Larson, G., Karlsson, E. K., Perri, A., Webster, M. T., Ho, S. Y. W., Peters, J., Stahl, P. W., Piper, P. J., Lingaas, F., Fredholm, M., Comstock, K. E., Modiano, J. F., Schelling, C., Agoulnik, A. I., Leegwater, P. A., Dobney, K., Vigne, J.-D., Vilà, C., Andersson, L. & Lindblad-Toh, K. 2012. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109, 8878-8883.

Lindblad-Toh, K., Wade, C. M., Mikkelsen, T. S., Karlsson, E. K., Jaffe, D. B., Kamal, M, Clamp, M., Chang, J. L., Kulbokas, E. J., Zody, M. C., Mauceli, E., Xie, X., Breen, M., Wayne, R. K., Ostrander, E. A., Ponting, C. P., Galibert, F., Smith, D. R., deJong, P. J., Kirkness, E., Alvarez, P., Biagi, T., Brockman, W., Butler, J., Chin, J.-W., Cook, A., Cuff, J., Daly, M. J., Decaprio, D., Gnerre, S., Grabherr, M., Kellis, M., Kleber, M., Bardeleben, C., Goodstadt, L., Heger, A., Hitte, C., Kim, L., Koepfli, K.-P., Parker, H. G., Pollinger, J. P., Searle, S. M. J., Sutter, N. B., Thomas, R., Webber, C., Broad Institute Genome Sequencing Platform, Baldwin, J., Abebe, A., Abouelleil, A., Aftuck, L., Ait-Zahra, M., Aldredge, T., Allen, N., An, P., Anderson, S., Antoine, C., Arachchi, H., Aslam, A., Ayotte, L., Bachantsang, P., Barry, A., Bayul, T., Benamara, M., Berlin, A., Bessette, D., Blitshteyn, B., Bloom, T., Blye, J., Boguslavskiy, L., Bonnet, C., Boukhgalter, B., Brown, A., Cahill, P., Calixte, N., Camarata, J., Cheshatsang, Y., Chu, J., Citroen, M., Collymore, A., Cooke, P., Dawoe, T., Daza, R., Decktor, K., Degray, S., Dhargay, N., Dooley, K., Dooley, K., Dorje, P., Dorjee, K., Dorris, L., Duffey, N., Dupes, A., Egbiremolen, O., Elong, R., Falk, J., Farina, A., Faro, S., Ferguson, D., Ferreira, P., Fisher, S., Fitzgerald, M., Foley, K., Foley, C., Franke, A., Friedrich, D., Gage, D., Garber, M., Gearin, G., Giannoukos, G., Goode, T., Goyette, A., Graham, J., Grandbois, E., Gyaltsen, K., Hafez, N., Hagopian, D., Hagos, B., Hall, J., Healy, C., Hegarty, R., Honan, T., Horn, A., Houde, N., Hughes. L., Hunnicutt, L., Husby. M., Jester, B., Jones, C., Kamat, A., Kanga, B., Kells, C., Khazanovich, D., Kieu, A. C., Kisner, P., Kumar, M., Lance, K., Landers, T., Lara, M., Lee, W., Leger, J.-P., Lennon, N., Leuper, L., Levine, S., Liu, J., Liu, X., Lokyitsang, Y., Lokyitsang, T., Lui, A., Macdonald, J., Major, J., Marabella, R., Maru, K., Matthews, C., McDonough, S., Mehta, T., Meldrim, J., Melnikov, A., Meneus, L., Mihalev, A., Mihova, T., Miller, K., Mittelman, R., Mlenga, V., Mulrain, L., Munson, G., Navidi, A., Naylor, J., Nguyen, T., Nguyen, N., Nguyen, C., Nguyen, T., Nicol, R., Norbu, N., Norbu, C., Novod, N., Nyima, T., Olandt, P., O’Neill, B., O’Neill, K., Osman, S., Oyono, L., Patti, C., Perrin, C., Phunkhang, P., Pierre, F., Priest, M., Rachupka, A., Raghuraman, S., Rameau. R., Ray, V., Raymond, C., Rege, F., Rise, C., Rogers, J., Rogov, P., Sahalie, J., Settipalli, S., Sharpe, T., Shea, T., Sheehan, M., Sherpa, N., Shi, J., Shih, D., Sloan, J., Smith, C., Sparrow, T., Stalker, J., Stange-Thomann, N., Stavropoulos, S., Stone, C., Stone, S., Sykes, S., Tchuinga, P., Tenzing, P., Tesfaye, S., Thoulutsang, D., Thoulutsang, Y., Topham, K., Topping, I., Tsamla, T., Vassiliev, H., Venkataraman, V., Vo, A., Wangchuk, T., Wangdi, T., Weiand, M., Wilkinson, J., Wilson, A., Yadav, S., Yang, S., Yang, X., Young, G., Yu, Q., Zainoun, J., Zembek. L., Zimmer, A. & Lander, E. S. 2005. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature 438, 803-819.

O’Regan, H. J. 2018. The presence of the brown bear Ursus arctos in Holocene Britain: a review of the evidence. Mammal Review 48, 229-244.

Padian, K. 1997. The rehabilitation of Sir Richard Owen. BioScience 47446-453.

Savolainen, P., Zhang, Y. P., Luo, J., Lundeberg, J. & Leitner, T. 2002. Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs. Science 298, 1610-1613.

vonHoldt, B. M., Pollinger, J. P., Lohmueller, K. E., Han, E. J., Parker, H. G., Quignon, P., Degenhardt, J. D., Boyko, A. R., Earl, D. A., Auton, A., Reynolds, A., Bryc, K., Brisbin, A., Knowles, J. C., Mosher, D. S., Spady, T. C., Elkahloun, A. Geffen, E., Pilot, M., Jedrzejewski, W. Greco, C., Randi, E., Bannasch, D. Wilton, A., Shearman, J. Musiani, M. Cargill, M. Jones, P. G., Qian, Z., Huang, W., Ding, Z.-L., Zhang, Y.-p., Bustamante, C. D., Ostrander, E. A., Novembre, J. & Wayne, R. K. 2010. Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature 464, 898-902.