Plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, mosasaurs and the other sea-going reptiles of the Mesozoic seas are among the most fascinating and awesome animals of all time. But if you want a comprehensive, well-illustrated book that reviews them all… well, you’re out of luck, since no such volume exists*. UNTIL NOW.

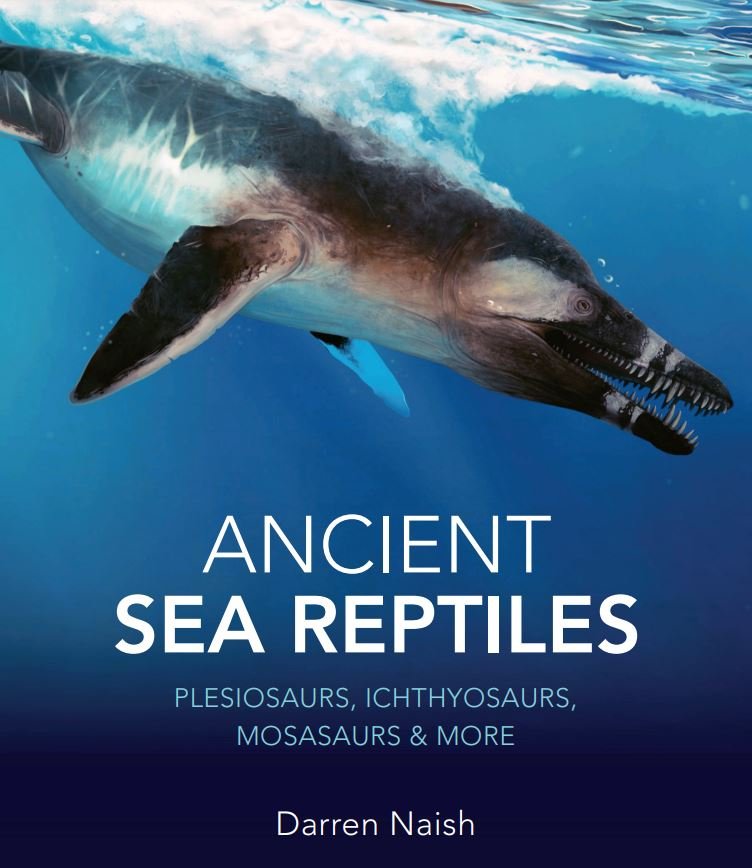

Yes, today see the publication of my new book Ancient Sea Reptiles (Natural History Museum in the UK; Smithsonian Books in the USA), and getting it published marks a major personal achievement. I’ve been trying for years to get such a book off the ground, but it’s the success of Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved (Naish & Barrett 2016) that’s allowed things to go forward. I can’t express how pleased I am that things have finally worked out.

* A French language book – La Mer au Temps des Dinosaures, by Nathalie Bardet, Alexandra Houssaye, Stéphane Jouve and Peggy Vincent – appeared while I was writing Ancient Sea Reptiles. I haven’t yet seen a copy and am unaware of how comprehensive it is.

Ancient Sea Reptiles is approximately similar in style and format to Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved but is substantially more focused on a ‘group-by-group’ arrangement of the animals it covers. The main chapters cover ‘lesser known’ marine reptile groups (including the Triassic hupehsuchians, thalattosaurs, placodonts, and nothosaurs, the Jurassic pleurosaurs, and the marine snakes of the Cretaceous), then the geologically longer-lived, physically more imposing ichthyosaurs, the diverse and often long-necked plesiosaurs, those phenomenal giant lizards the mosasaurs and, finally, the sea turtles.

Caption: if you want to know about a relatively obscure group like the thalattosaurs, where do you go? That’s a problem, since such animals are generally not covered in the available non-specialist literature. Ancient Sea Reptiles discusses this group and so many others. These illustrations show (at left, top to bottom) the skulls of an unnamed Chinese taxon, Nectosaurus and Hescheleria and (at right) Hescheleria as it might have looked in life. Images: Tosha Hollman, from Naish (2022).

Introductory chapters cover Mesozoic marine reptiles more generally. Chapter 1 reviews our understanding of Mesozoic marine palaeogeography and climate as well as the scientific discovery of Mesozoic marine reptiles. Chapter 2 covers extinction events and broad evolutionary relationships. And chapter 3 covers anatomy, functional morphology and biomechanics, the focus being on swimming, feeding biology, the plesiosaur neck, and skin anatomy and life appearance.

Caption: our view of what Mesozoic marine reptiles were like in life have changed substantially the more we’ve learnt. The Crystal Palace models from the 1850s represent interpretations that - in cases - persisted until surprisingly recently. Clockwise from upper left: the thalattosuchian Steneosaurus, the mosasaur Mosasaurus, the ichthyosaur Ichthyosaurus, the plesiosaur Plesiosaurus. Images: Darren Naish.

An inevitable personal perspective. I began my academic career as someone hoping to go into Mesozoic marine reptile studies. Ultimately, it wasn’t to be (I got side-tracked into dinosaurs), but I very much remember the 1990s-era realisation that things were changing fast. The stereotypical view mostly conveyed beforehand – at least, so far as I understood it from books – was that these animals were static in evolutionary terms, that they weren’t remarkable with respect to biomechanics, and that they’d spent their history in stable, constantly warm conditions.

Clear signs of change came from a 1993 article by Robert Bakker in which he argued for a complex, dynamic view of Mesozoic marine reptile evolution that turned the then ‘traditional’ view of plesiosaur phylogeny on its head (Bakker 1993). Meanwhile, a series of studies published by Arthur Cruickshank, Mike A. Taylor and their colleagues in the UK showed that plesiosaurian skulls were sophisticated and specialised with respect to biting, stress dissipation and perhaps sensory abilities too (e.g., Cruickshank et al. 1991, Cruickshank 1994, Storrs & Taylor 1996, Taylor 1992).

Caption: a montage depicting various of the publications and proposals that made it clear (speaking from a personal perspective) that things in the world of Mesozoic marine reptiles were becoming more interesting during the late 1980s and early-and-mid 1990s. Clockwise from upper left: one of Mike Taylor’s diagrams of plesiosaurian jaw musculature, from his 1992 paper on Rhomaleosaurus; one of Riess & Frey‘s 1991 depictions of the alternating downstroke model of plesiosaur locomotion; my redrawing of the (still controversial) hydrodynamically driven underwater olfaction model of Cruickshank et al. (1991); and one of Taylor’s diagrams of ichthyosaur buoyancy and propulsion, from a 1987 paper in Palaeontology.

Renewed interest in the swimming biology of plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs – something that kicked off in the mid-1970s (Robinson 1975) – was present by the early 1990s and had even snuck into popular venues like New Scientist. And new specimens and species from Antarctica, Niger, Nigeria, Angola, Mexico, Cuba, Chile and Argentina were making it clear that Mesozoic marine reptile research was very much a global event: the traditional Eurocentric view of marine reptile diversity and evolution (on which more in a moment) was very likely highly misleading.

A Mesozoic Marine Reptile Renaissance. While not fronted by a bombastic individual or a specific pop-sci piece – there’s no ‘Dinosaur Renaissance’ article in Scientific American for Mesozoic marine reptiles – it was obvious by the mid-1990s that a quiet revolution was happening, and that more and more people were being attracted to the study of plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs and the others. This wasn’t due to a specific claim or contention made about the animals, but instead to the realisation that a substantial number of interesting questions about them had essentially never been asked. I see the publication of the 1997 book Ancient Marine Reptiles, edited by Jack Callaway and Elizabeth Nicholls, as proof that a Mesozoic Marine Reptile Renaissance was underway and obvious by the mid-1990s, even to non-specialists.

Caption: Callaway & Nicholls’s 1997 Ancient Marine Reptiles, the first substantial 20th century book devoted to Mesozoic marine reptiles since Samuel Williston’s 1902 Water Reptiles of the Past and Present. It’s multi-authored and includes 17 separate contributions. Like so many academic books, it’s prohibitively expensive should you wish to obtain it for yourself today.

In my writings on the history of dinosaur research (Naish & Barrett 2016, Naish 2021), I’ve been accused of talking about the ‘Dinosaur Renaissance’ too much (this being the sociocultural event, mostly led by Bakker and other vociferous scientists in the USA, in which it was argued that the biology, diversity and evolution of dinosaurs was substantially more interesting than the ‘conventional’ narrative). But, alas, I’m unable to ignore the fact that I’ve seen a major scientific and cultural paradigm change occur in real time. It’s such a big deal.

I feel the same way about Mesozoic marine reptiles. It might not be obvious to young researchers and enthusiasts today – they’re living in the Shiny Future of the 2020s where everything is different – but things really have changed a lot over the past several decades, and this is a story that mostly hasn’t been conveyed.

Caption: among the many interesting phylogenetic hypotheses pertinent to Ancient Sea Reptiles are (as shown at left) those positing how thalattosaurs, hupehsuchians, ichthyosaurs, saurosphargids and sauropterygians might all be close kin, and (at right) the alliance of cryptoclidids and xenopsarians within Plesiosauria. The book includes numerous cladograms that I designed and illustrated myself. Images: Darren Naish.

Ancient Sea Reptiles aims to make this point obvious. The evolution of Mesozoic marine reptiles wasn’t static and about long stretches of conservatism, but dynamic and complex, with major overturns and innovations happening right to the end. Plesiosaur phylogeny, it turns out, is hilariously complicated, the several fully pelagic mosasaur groups might have evolved their pelagic specialisations independently from less specialised ancestors, and pelagic sea turtles – similarly – might have evolved twice, from different ancestors.

Mesozoic marine reptiles didn’t live in a stable hothouse world, but a changeable one affected by major tectonic and volcanic events, and they had to deal with significant environmental changes and even ice ages.

Caption: the idea that Mesozoic climates were eternally equable and stable hasn’t been valid or defensible for decades now. This graph shows isotopic data recovered from Early and Middle Jurassic shelly fossils from Europe. The data reveal very high sea surface temperatures in parts of the Toarcian (that big red ‘low point’) but cool and even cold temperatures in the Aalenian in particular. Image: Korte et al. (2015).

And far from being uninteresting from the point of view of anatomy and functional morphology, there are reasons for thinking that Mesozoic marine reptiles include some of the most extreme animals that have ever evolved, with incredible innovations in jaw and tooth morphology, neck anatomy, propulsion and more. For elaboration on that fairly nebulous point, I’ll have to direct you to the book!

On Eurocentricism and going beyond it. For all this talk of newness and paradigm shifts, one aspect of Mesozoic marine reptile research that makes the subject both eternally frustrating and fascinating is the historical 17th to 19th century angle that ties the topic to the geological locations of western Europe. Will we ever stop talking about the Dorset coast and Mary Anning, the Solnhofen Limestone, Monte San Giorgio in Switzerland, the German Posidonia Shale, Holzmaden and the Oxford Clay of the English midlands?

It seems not. The fossils of Mesozoic marine reptiles might, by now, have been found worldwide but it remains the case that western Europe remains important. A great paradox of the Mesozoic marine reptile fossil record is that a good number of groups remain almost unique to this region, this creating the impression that they scarcely occurred elsewhere. Were these animals really provincial (something that seems unlikely given their adaptation for pelagic life)? Or is it that our knowledge is still very much in its infancy?

Caption: if an animal like Temnodontosaurus is known only from western Europe and western Chile, what should we infer about its actual distribution when it was alive? Images: (c) Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London; (c) Deep Time Maps.

In the book, I present reasons for thinking that the latter is the case. My favourite example is provided by the long-bodied temnodontosaurian ichthyosaurs of the Early Jurassic. These large to stupendously large, wholly pelagic predatory ichthyosaurs are exclusive to western Europe… bar a single chunk of jaw from Chile. If we look at an Early Jurassic palaeomap, an occurrence in western Europe and western South America implies a near-global geographical range. Oh, for a better understanding.

Having mentioned Mary Anning: I do, of course, provide a dedicated section on the most famous fossilist of all time, a woman considered by many a patron saint of palaeontology. Anning’s impact on our understanding of Jurassic marine life was revolutionary. If only she had some way of knowing, when alive, how important she would be in future decades. A few aspects of the Anning story, however, have very often been mis-framed, among them the claim that she’s been “overlooked” or “forgotten”.

Caption: just how many palaeontologists get immortalised as action figures? Yes, I own a small plastic Mary Anning, and you should get your own too. It was made by splendidhand toys but it looks like they’re not selling that specific figure right now.

Art and imagery. As should be obvious from this blog, and from the look of my various books and other publications, I really care about pictures. I’m pleased to say that Ancient Sea Reptiles is extremely well illustrated, featuring numerous specimen photos, life reconstructions, skeletal diagrams, cladograms and so on throughout. It goes without saying that we used what photos we could of specimens that are on show at the Natural History Museum, or in its collections.

Caption: huge thanks to Brian Choo for allowing use of these excellent Triassic marine scenes, depicting life in the Guizhou (left) and Guanling faunas of the Middle and Late Triassic, respectively. Tanystropheus, nothosaurs, pachypleurosaurs and thalattosaurs are visible in the image at left; archaic ichthyosaurs, thalattosaurs, placodonts and turtles are visible in the one at right. Oh, also fishes. Images: Brian Choo, used with permission.

But we also went to some trouble to feature reconstructions produced by some very skilled artists, among them Davide Bonnadonna, Brian Choo, Julius Csotonyi, Tosha Hollmann, Joschua Knüppe, Julia Lacerda, Robert Nicholls, Júlia d’Oliveria, Scott Reid, Gabriel Ugueto and Esther van Hulsen. Huge thanks to everyone who submitted work to the book, and I hope you’re happy with the way in which it’s presented. The UK and US issues have different covers, but both are spectacular. The UK cover is by Haider Jaffri and the US one by Robert Nicholls.

While I could say a lot more, that’s where I’ll end. Already several publications have appeared that outdate a few of the contentions made in the book, but such is the nature of writing about a fast-moving, dynamic field of research. Hopefully they can be incorporated into the second edition.

Ancient Sea Reptiles is available from the Natural History Museum (at £20) if you’re in the UK, and from Smithsonian Books (at $29.95) if you’re in North America. And I’ll say again that finally seeing this book in print is a dream come true. I hope those of you that buy it enjoy it.

For previous articles on Mesozoic marine reptiles, see…

The skin of ichthyosaurs, September 2008

Sea Dragons of Avalon, an Arthurian adventure (part I), August 2009

Who made the giant Jurassic sea-floor gutters?, December 2009

Prediction confirmed: plesiosaurs were viviparous, August 2011

Rigid Swimmer and the Cretaceous Ichthyosaur Revolution (part I), January 2012

Plesiosaurs and the repeated invasion of freshwater habitats: late-surviving relicts or evolutionary novelties?, January 2013

Malawania from Iraq and the Cretaceous Ichthyosaur Revolution (part II), May 2013

Can’t get me enough of that sweet, sweet Temnodontosaurus, January 2014

Plesiosaur Peril — the lifestyles and behaviours of ancient marine reptiles, March 2014

Ancient Marine Reptiles Had Absurd, Complex Nostrils, July 2014

The Unique and Efficient 4-Flipper Locomotion of Plesiosaurs, August 2017

The Fall and Rise of Protoichthyosaurus, October 2017

Up Close and Personal With the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, December 2018

The Ichthyosaurs of the Kimmeridge Clay, March 2021

History of the Iraqi Ichthyosaur, April 2021

Refs - -

Bakker, R. T. 1993. Plesiosaur extinction cycles - events that mark the beginning, middle and end of the Cretaceous. In Caldwell, W. G. E. & Kauffman, E. G. (eds) Evolution of the Western Interior Basin. Geological Association of Canada, Special Paper 39, 641-664.

Cruickshank, A. R. I. 1994. Cranial anatomy of the Lower Jurassic pliosaur Rhomaleosaurus megacephalus (Stutchbury) (Reptilia: Plesiosauria). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 343, 247-260.

Cruickshank, A. R. I., Small, P. G. & Taylor, M. A. 1991. Dorsal nostrils and hydrodynamically driven underwater olfaction in plesiosaurs. Nature 352, 62-64.

Naish, D. 2022. Ancient Sea Reptiles. Natural History Museum, London.

Naish, D. & Barrett, P. M. 2016. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. The Natural History Museum, London.

Robinson, J. A. 1975. The locomotion of plesiosaurs. Neues Jahrbuch fur Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen 149, 286-332.

Storrs, G. W. & Taylor, M. A. 1996. Cranial anatomy of a new plesiosaur genus from the lowermost Lias (Rhaetian/Hettangian) of Street, Somerset, England. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16, 403-420.

Taylor, M. A. 1992. Functional anatomy of the head of the large aquatic predator Rhomaleosaurus zetlandicus (Plesiosauria, Reptilia) from the Toarcian (Lower Jurassic) of Yorkshire, England. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 335, 247-280.