If you read the previous article – recapping the events of TetZooCon 2024 – you’ll know that things went well. But what was that cryptic mention toward the end of a tour?

Caption: basic ingredients for a TetZooTour… (1) a snazzy coach, (2) stops at hotels, (3) dinosaurs in museums (here, a cast of the T. rex specimen AMNH 5027), (4) perplexing taxidermy (here, a koalabat at the Horniman Museum). Images: Darren Naish.

Yes: for the first time ever, I decided to run an official TetZooTour of southern England, the aim being to take a number of guests to such attractions as museums, zoological parks and palaeontological sites. On the morning of Monday September 30th – yeah, the next morning after TetZooCon, what was I thinking? – I and around 25 other people boarded a beautiful, brand-spanking-new tour coach at our designated pick-up in central London, and off we went. I’ve worked as a tour guide in the past and am aware of how much information has to be compiled in advance. Working in co-operation with Marc Bacon of South East Coaches, a tour was devised that would involve three days of travel, two overnight stays at hotels, and stops at a number of TetZoo-relevant locations.

Caption: we board and prepare to leave London. Our pick-up and drop-off points were essentially right next to the TetZooCon venue (Bush House, Kings College), and you can’t get more convenient than that. Images: Darren Naish.

Dinosaur rEvolution at the Horniman. I’m pleased to say that everyone arrived on time, and off we went to the first of our stops: the Horniman Museum and Gardens in Forest Hill, London, specifically to see the exhibition Dinosaur rEvolution. This is one of those separately ticketed exhibitions that’s not part of the museum’s main galleries, and its time at the Horniman is due to come to an end within the next few weeks. It’s based around the work and art of palaeoartist Luis Rey and I’m very pleased to report that Luis was able to accompany us and give us what was effectively a guided tour. The roaring dinosaur sounds sure made it hard to speak to a group, but we managed.

Caption: the outside of the Horniman Museum, as seen from the South Circular Road looking north. The museum opened to the public in 1901 and is named for its founder, Frederick John Horniman (1835-1906), who collected numerous items as a consequence of lifetime ownership of the Horniman Tea Company. The history of British tea companies is something else and in part involves Britain’s exploitation of Victorian China and its opium production. Image: Darren Naish.

I hadn’t seen the exhibition before and was impressed. While broadly functioning as a showcase of Luis’s art (and with his famous ‘chicken’ Deinonychus – not my term! – at centre stage), it’s designed to show how two of the main dinosaurian lineages (Theropoda and Ornithischia) evolved and existed in parallel, only one persisting beyond a certain mass extinction you might have heard of.

Caption: a (roughly) life-sized model of the Early Cretaceous North American dromaeosaurid Deinonychus, in the red-wattled, vibrantly feathered guise invented by Luis and used in his books. Incidentally, the dappled lighting across the model isn’t a random effect: I might be wrong, but I think we’re seeing light being projected through an image of a thin section of sauropod bone. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: at left, Luis Rey talks therizinosaurs to our tour group while standing alongside a replica skeleton of the large, North American Nothronychus mckinleyi. The large hand claws, small teeth, long and slender neck and large overall size of this animal are among the key distinctive features of this theropod group. At right, a closer view of the skeleton with some of Luis’s artwork making an appearance at edge of frame. Images: Darren Naish.

The exhibition features a large number of cast or replica fossils, including of archaic birds and other maniraptorans, a posed and mounted Velociraptor, Avimimus, the therizinosaurs Falcarius and Nothronychus, a T. rex skull, the David Sole scelidosaur, the famous tail-bristled Psittacosaurus, and several ceratopsid skulls. There are also several life-sized (or half life-sized) models, some animatronic, plus there are copious panels and art. That’s a lot of stuff.

Caption: ceratopsid ceratopsian skulls on show at Dinosaur rEvolution. In the image at left, we see (l to r) Diabloceratops, Kosmoceratops and Coahuilaceratops. The photo at right shows Coahuilaceratops on its own. This animal is supposed to have especially massive horns relative to the rest of its skull but, as you can see, it’s not entirely obvious that this is true. Images: Darren Naish.

It was a great opportunity to hear Luis recount his personal journey of discovery with respect to feathery and filamentous dinosaur fossils. As I’ve said before, he’s one of several artists who feels vindicated by 21st century discoveries: the decision to put feathers and spiny quills on Mesozoic dinosaurs always was a good one, and those scientists who – back in the 1990s – made Luis remove feathers from his illustrations don’t look prescient today. It’s difficult to say because it often sounds targeted at individual scientists and authors, and thus rude, but the conservatism so prevalent in the popular British dinosaur-themed literature and exhibitions of the 1980s, 90s and 2000s didn’t do us any favours. We’re stuck with work from that age that was decidedly lacklustre and uninspiring when new, let alone today. I predict that history will be kind to Luis Rey for promoting an avant-garde radicalism that proved broadly correct in the end.

The Horniman has other exhibits that are worth looking at, but their natural history gallery is currently closed, meaning that we couldn’t get to see the famous walrus or the various vintage palaeontology-themed displays. The walrus is famous because the taxidermist who prepared it incorrectly made it monstrously rotund in order to smooth out the wrinkles.

Caption: the Horniman Museum has a connection with mermaids thanks to study of this specimen, obtained by London’s Wellcome Trust in 1919, transferred to the Horniman Museum in 1982, and studied recently by Paolo Viscardi and colleagues. Coincidentally, Paolo spoke about this specimen and his work on it (Viscardi et al. 2014) at the very first TetZooCon of 2014. This work showed that the old story about mermaids like this being fish and monkey parts stitched together is not at all correct. Image: Darren Naish.

To the south and the west! And that was that for London; we bade farewell to the capital and headed out west, our destination for the evening being Bournemouth on the south coast of Dorset. To get there, we travelled through the New Forest – a fascinating area of the British countryside that I know well – and the Great Heath that surrounds Bournemouth town. How is it that Britain includes these large and not especially young, relatively open areas given the traditional view that prehistoric Britain was thickly forested north to south, east to west? We now think that ancient Britain was more of a habitat mosaic, with parkland-like areas existing between more wooded ones. This concept will be familiar to you if you’ve read Isabella Tree’s book Rewilding (Tree 2018) or – good for you – kept up to speed with publications on Britain’s prehistoric pollen record (Fyfe et al. 2013).

Caption: this image – showing Acres Down near the centre of the New Forest – wasn’t taken on the tour, but it depicts the sort of mosaic, partly open habitat that characterizes this famous area of south-west England. Is this a new thing, historically speaking, or do spaces like this have a long history in the British countryside? Image: Darren Naish.

In Bournemouth, we stayed in Boscombe, an attractive, tree-lined part of the city, and at a hotel just a couple of minutes away from the headquarters of the Bournemouth Natural Science Society (or BNSS). This has a natural history museum of its own that includes a palaeontological collection with numerous Jurassic marine reptile fossils. I tried and failed to get us special out-of-hours access, oh well.

Palaeo-Mecca, the fabled town of Lyme Regis. Why stay in Bournemouth? To be within easy reach of one of the world’s most famous palaeontological and geological locations, the south Dorset, seaside town of Lyme Regis. I’m lucky enough to have visited Lyme Regis many times, but many interested people – and not just those from abroad – have never had this privilege. The town is not exactly built for coaches (it has steep hills, narrow roads and very tight corners) but we got there and disembarked in perfect weather, only a day or two after moderately heavy winds and waves had swept along the coast. That was good, since it meant that fresh erosion had occurred across the cliffs and beaches, and that’s ideal when looking for fossils.

Caption: the Lyme Regis coast looking east, with East Cliff Beach (where we did our fossil hunting) visible in about the middle of the shot. The tide is out, exposing the wavecut platform along the shore. The vegetated strip inshore is home to numerous insects, and I recorded several interesting species on the day. Image: Darren Naish.

Literally on stepping off the coach we were met by palaeontologist and Lyme Regis Museum engagement and collections officer Dr Natalia Jagielska who had prepared a bespoke itinerary based on the things I wanted us to see. After a tour of Lyme Regis Museum and a talk on fossils and fossil-finding, we trekked to the amazing East Cliff Beach for an hour or so of fossil finding. This was timed to match low tide, of course. A good number of fossils were found, including attractive ammonites and bivalves, and partial belemnites and crinoids. Alas, no vertebrates of any sort (that’s not a ridiculous idea. I’ve found isolated ichthyosaur vertebrae on two previous occasions).

Caption: Lyme Regis Museum is a small but excellent museum, a must-visit if you’re interested in the history of the town or in its geology or palaeontology. Several key Jurassic marine reptiles, fishes and other animals are on show, as is associated art and sculpture. Images: Darren Naish.

We then visited the Mary Anning statue (where obligatory group photos and such were taken) before visiting the Anning family grave, another famous photo stop for people interested in palaeontology and its history.

The Lyme Regis dinosauroid. Then it was time for Dinosaurland, properly Dinosaurland Fossil Museum. I haven’t visited Dinosaurland for many years and was surprised by how different it looked relative to my previous visit (which probably happened more than 15 years ago). Dinosaurland is a converted former congregational church (Mary Anning was baptised there in 1799, and worshipped there until her conversion to Anglicanism during the 1830s) and features room after room of fossils of all sorts: over 20,000 in all. A mezzanine is home to a series of prehistoric dioramas that depict ancient life from the Silurian (or thereabouts) to the end of the Cretaceous. As you can see, the dioramas are of that special home-made quality that somehow combines impressive craftsmanship with pure distilled nightmare fuel.

Caption: the front of Dinosaurland Fossil Museum in Coomb Street, Lyme Regis. The museum’s ground-floor section has a one way system that is not great if you suffer from claustrophobia, but the building is fun overall. The tree fern on the right adds a Mesozoic vibe to the exterior. Image: Darren Naish.

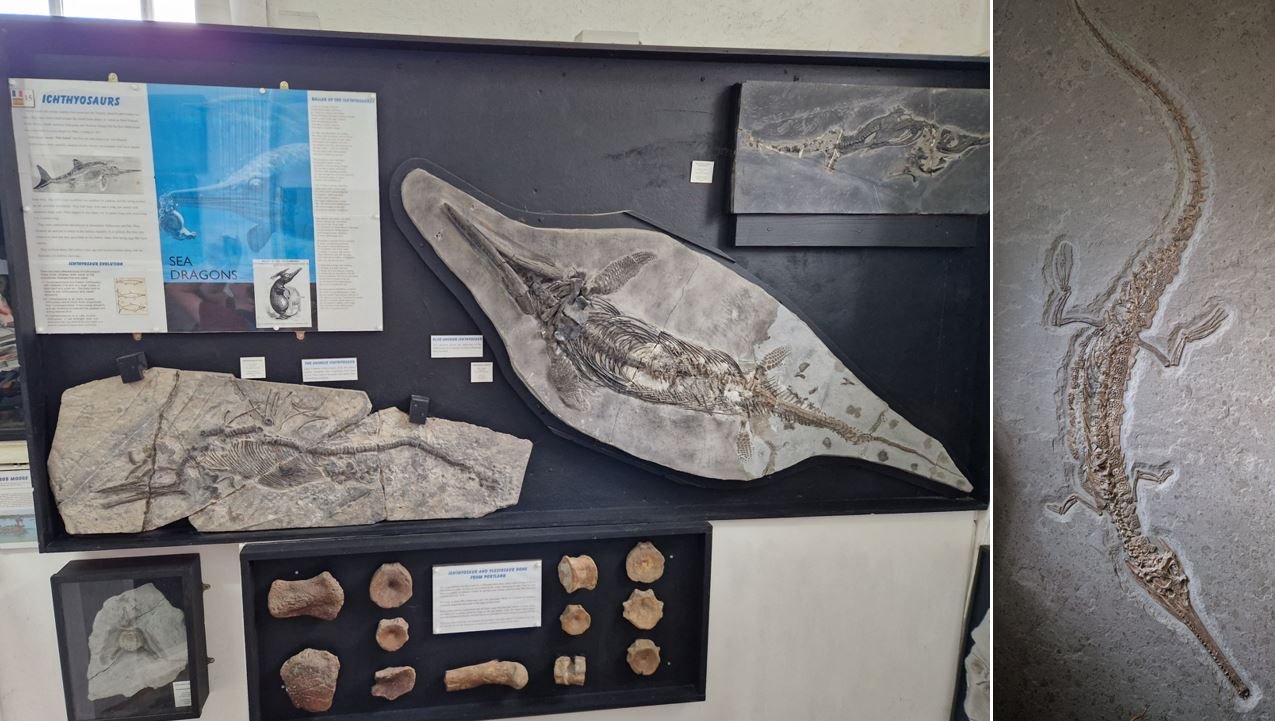

Caption: a fossil Mesozoic marine reptile montage from Dinosaurland, showing ichthyosaurs at left and a teleosauroid thalattosuchian at right. Hey, did I mention that I wrote a book on Mesozoic sea reptiles? I understand that it’s sold out in a lot of places now. Images: Darren Naish.

Caption: a model like this (it’s big: somewhere round about 6 m long) has various technical, anatomical inaccuracies. But imagine building a big model like this yourself, with affordable materials. I think it’s actually pretty good. It depicts the British spinosaurid Baryonyx walkeri. Image: Darren Naish.

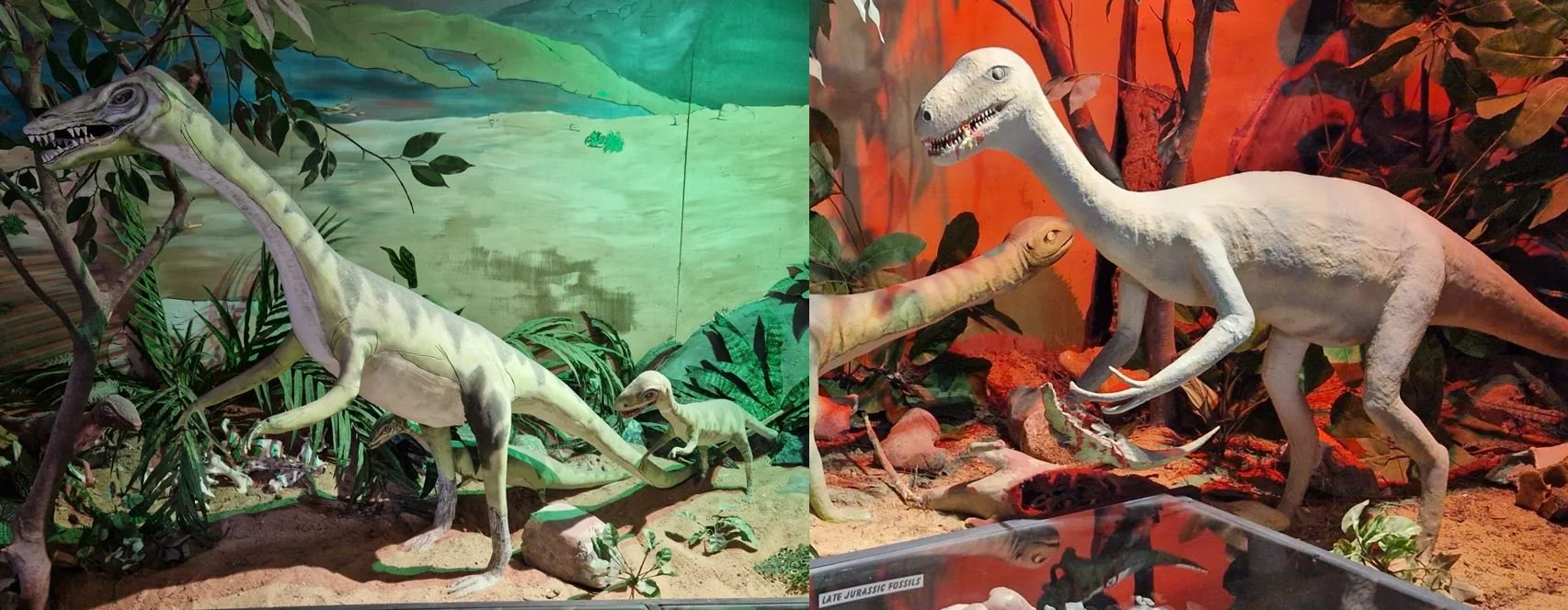

Caption: dinosaur-themed dioramas from the mezzanine section of Dinosaurland. At left, an Early Jurassic scene depicting what I think is a Coelophysis adult and juvenile. At right, a Late Jurassic scene that shows (perhaps) Ornitholestes (holding a lepidosaur of some sort in its right hand), with a geologically older sauropodomorph peeking in at left. The look of these models remind me of illustrations from Michael Tweedie’s 1977 book The World of Dinosaurs, and might be based on them. Images: Darren Naish.

I was there for one model in particular. Tucked away at the end of the dioramas and in its own glass case is ‘Saurian’, a very English version of Dale Russell and Ron Séguin’s dinosauroid model of the early 1980s. Dinosaurland’s ‘Saurian’ isn’t, technically or artistically, quite on par with the Canadian original, and an accompanying information sheet doesn’t really explain its backstory: it notes that the model depicts what “dinosaurs could have looked like if they had survived to the present day” (what… all of them?) but it doesn’t make reference to Russell and Séguin’s project nor explain how its appearance is based on that of their very excellent model.

Caption: Dinosaurland’s infamous ‘saurian’ model, one of several similar models present worldwide. As might be obvious from the image at right, we had fun having our photo taken nearby. Thanks to the anonymous museum-goer who kindly took this photo for me. Images: Darren Naish; anonymous museum-going woman.

It does, however, have a valid connection to the real dinosauroid in Canada because the reaction of naïve visitors to its presence is tellingly similar. As Will Tattersdill and I recounted in our 2021 article on the dinosauroid (Naish & Tattersdill 2021), people encountering the model for the first time (and unaware of its backstory) assume that it’s a misplaced alien. The similarity of the dinosauroid with certain fictional aliens is not coincidental given that Dale Russell was interested in, and very much aware of, humanoid alien stories: one of the ideas he was driving at is that humanoids were inevitable and – potentially – a widespread part of evolutionary history across the cosmos (Naish & Tattersdill 2021).

And that was that for Lyme Regis. A few members of our group took time to visit various of the shops and eateries about the town, but it would have been good to spend more time there. Alas, we only really had a few hours in Lyme Regis since arriving late and leaving early is all part of the coach tour experience (it has to be because of leaving, and getting to, hotels). I’ll keep that in mind for the future though.

Caption: our group at one of several Mary Anning-themed stops in the town, namely the family grave. It has become traditional to leave both flowers and fossils at the grave. Its location at the very front of the graveyard is not coincidental, and is related to the fact that she is its most famous resident. Image: Darren Naish.

I owe massive thanks to the Lyme Regis Museum staff – Natalia in particular – for doing such a phenomenal job in hosting us and enabling us to see everything I hoped we would. We left on time, and struck out east, heading this time to England’s south-east, and specifically Folkestone on the coast of Kent.

At the coast of Kent. Our second hotel stay was at the large, coast-side Grand Burstin Hotel in Folkestone. One of the concerns when leading a tour is that hotels can take a long time – more than an hour – to register all members of a large group, something that can be tedious and problematic when you’re arriving late, or behind schedule. I’m very pleased to say that we had none of that, and that our hotels were fully prepared for our arrival. A number of us stayed up too late in the bar. I don’t remember why, but I think that mekosuchines and books on sauropods were mentioned at one point or another.

Caption: the morning view from my room at Folkestone. For reasons, I got upgraded to an executive suite but don’t tell the others. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: Folkestone Harbour on the morning of our departure, showing the swing bridge and some attractively textured sediment. Looks great in nice weather. Image: Darren Naish.

The reason for our stay in Folkestone is that our final excursion was to Howletts Wild Animal Park – often called Howletts Zoo or just Howletts – for a day of zoo-going. There’s a lot to say about Howletts, in part because the zoo is synonymous with the late John Aspinall and a fairly notorious former safety record. I was careful on our approach to emphasize that this is nothing for a visiting tour party to worry about, since the relevant incidents have all involved keepers. Anyway, the drive from Folkestone to Howletts is not a long one and we arrived before the zoo was even open, giving us time to obtain the group photo you see here.

Caption: our group outside Howletts. I’m in this photo so obviously didn’t take it. The mammoth with the massive dome on its head is very distinctive and various models of this likeness are scattered about the outdoor attractions of the UK. This is the second image here that features a photobomb from a dinosaur. Image: Marc Bacon.

Animals at Howletts. Due to a technical fault that was absolutely not due to me forgetting to charge the battery, my camera was inoperative during my time at Howletts, so no good photos… oh, how that hurts. Howletts is a reasonably large zoo and I built our itinerary on the assumption that we might get to see about half of what the zoo has on show. But no, in the end we had time to do it all, despite the inconvenience of a brief, heavy rain shower.

The zoo is wholly mammal-focused (ostriches are present in one enclosure but that seems to be it for non-mammals) and is especially strong on primates, big hoofed mammals, cats and wild dogs. Beginning with African lion Panthera leo, Giant anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla, Lowland tapir Tapirus terrestris, bongos (specifically the rare Keynan Mountain bongo Tragelaphus eurycerus isaaci), Sumatran tiger P. tigris sumatrae, Amur leopard P. pardus orientalis, Snow leopard P. uncia and more, we walked west to have lunch at the Pavilion Restaurant before heading north and back east to complete the circuit.

Caption: the lack of a functioning camera means that I had to rely on my phone, but the photos it takes aren’t all that bad. Left to right: Servals Leptailurus serval (one of which is carrying a deceased rodent in its mouth), juvenile lions (one of which had a deformed hindfoot), and East Javan langur or Javan lutung Trachypithecus auratus. Images: Darren Naish.

Animals seen on the second half include European wolf Canis lupus, Mainland clouded leopard Neofelis nebulosa and Caracal Caracal caracal, and we finished at the large, field-like enclosures that are home to African savannah elephant Loxodonta africana and Black rhino Diceros bicornis.

Caption: my photos might not be at all great, but at least a few other people on the visit did have good cameras with them. At left, a Sumatran tiger. At right, a male Western lowland gorilla Gorilla gorilla gorilla with an especially impressive head dome. I think that this is Djanhou, born at Howletts in 1993 and father to eight offspring. Images: Zach Wait.

Life-sized fossil mammals. An interesting feature we just had to look at was the outdoor Ice Age Mammals exhibit where a number of life-sized models of fossil mammals – and not all of them from the ‘Ice Age’ (meaning the Pleistocene) – are arranged in a wooded area in the north of the zoo. As you can see, some of the models are not that bad. Others are bad indeed. A concern I have is that many are equipped with full coats of simulated fur. While I’m not sure, I’m reasonably confident that this is fake and plastic, and I wonder if we have to worry about such material being shed into the environment and thereby contributing to plastic pollution.

Caption: models from near the end section of the outdoor fossil mammal exhibit, depicting a Woolly mammoth and the giant Asian rhino Elasmotherium sibiricum. I agree with arguments that Elasmotherium didn’t have an immense keratinous horn like this, but instead possessed a rounded, more dome-like, keratinous structure. It’s important to recognise how big Elasmotherium is: its skull is about 75 cm long. Images: Darren Naish.

Anyway… the exhibit included not only stalwarts like Woolly mammoth Mammuthus primigenius, Smilodon and a mega-horned version of Elasmotherium, but a dinoceratan (I think Eobasileus), the twin-horned Arsinotherium and an especially terrifying rendition of the stem-whale Ambulocetus. It turned out that we moved through the exhibit the wrong way round, since we started in the Pleistocene and ended up in the Late Cretaceous, rather than vice versa. The sole Cretaceous feature, if you’re wondering, is a Triceratops skull covered in clambering little Purgatorius.

Caption: models from near the middle section of the fossil mammal exhibit. The dinoceratan at left is just about the only model you can approach closely, as I’m doing here. The top of its head and shoulders had a smattering of small bloody chunks and feather tufts about them, showing that the model had recently been used as a plucking perch by a raptor (likely a sparrowhawk). At right: a scary Ambulocetus. I don’t think that this is a good look for the animal. I’ve reconstructed it several times myself and both the head shape and tooth configuration shown here aren’t right. Images: Zach Wait; Darren Naish.

And that was that. We had time to visit the shop and were fully boarded and ready to head back to our London drop-off point precisely on time. Traffic in London is notoriously difficult, but we made good and reached the drop-off just before 5pm, as planned. We then had a bit of trouble with our otherwise dependable wheelchair lift, but this was fixed after a little while and wasn’t disruptive in the end.

And that was the first TetZooTour. What a win! Everything ran to time, nobody got lost or injured, and we got to all of our stops and venues as planned with no disruptions or diversions. Each and every one of the tour-goers did us proud in terms of keeping to time and functioning as part of a group. I had a great time and the feedback I’ve received so far is positive.

Setting up and running this tour was a total gamble and I had no idea whether enough people would pay up and want to come along, but in the end they did, and costs were covered. It should also be obvious that the whole thing was a lot of fun and that I found it rewarding. It’s too early at this stage to be sure that a repeat performance will be happening next year (and beyond) but – right now – I consider it likely that it will, with different stops and different TetZoo-relevant attractions. Remember that, whatever happens, it’ll be part of DinoCon from 2025.

Caption: our shiny new coach. It served us well. Image: Darren Naish.

It only leaves me to say thanks once more to Marc (our driver and co-organizer) and South East Coaches, to Luis Rey and staff at Horniman Museum and Gardens, to Natalia and other staff at Lyme Regis Museum, and to those fine people who opted to join me. And that was the very first TetZooTour.

For previous articles on TetZooCon, see…

The events of TetZooCon 2014, July 2014

TetZooCon 2015 Is On, July 2015

The Events of TetZooCon 2015, November 2015

Coming Soon: TetZooCon 2016, September 2016

The Day After TetZooCon, October 2016

The Fourth TetZooCon, September 2017

The TetZooCon of 2017, October 2017

Reasons to Attend TetZooCon 2018, September 2018

TetZooCon 2018: Best TetZooCon So Far, October 2018

Announcing TetZooCon 2019 – the Biggest Yet, August 2019

Final Call For TetZooCon 2019, October 2019

The Sixth TetZooCon, October 2019

TetZooCon 2020 + Zoom = TETZOOMCON 2020, December 2020

TetZooMCon 2020 an Unbridled Success, December 2020

Cronch Cats, Beasts of Gévaudan, Dinosauroids, Mesozoic Art and Much More: TetZooMCon 2021 in Review, September 2021

The Ninth and Largest of the Tetrapod Zoology Conventions, December 2022

Announcing the 10th Tetrapod Zoology Convention, October 2023

At TetZooCon 2023, November 2023

TetZooCon 2023 the report, December 2023

The Last TetZooCon, October 2024

Refs - -

Fyfe, R. M., Twiddle, C., Sugita, S., Gaillard, M.-J., Barratt, P., Caseldine, C. J., Dodson, J., Edwards, K. J., Farrell, M., Froyd, C., Grant, M. J., Huckerby, E., Innes, J. B., Shaw, H. & Waller, M. 2013. The Holocene vegetation cover of Britain and Ireland: overcoming problems of scale and discerning patterns of openness. Quaternary Science Reviews 73, 132-148.

Tree, I. 2018. Rewilding: The Return of Nature to a British Farm. Pan Macmillan, London.

Viscardi, P., Hollinshead, A., MacFarlane, R. & Moffatt, J. 2014. Mermaids uncovered. Journal of Museum Ethnography 27, 98-116.