In 1999, the BBC TV series Walking With Dinosaurs aired on British TV. In the previous article, I discussed some of my recollections as a ‘witness’ of unfolding events. In this second article, we continue…

Caption: I am - as I hope is clear from these articles - an advocate of WWD’s aims and achievements. It was a force for good. But it remains the fact that some of its models were, alas, not good at portraying the life appearance of the animals concerned. The T. rex in particular is problematic. Image: (c) WWD/BBC.

WWD on TV, late 1999. And so we move on to the later months of 1999. WWD premiered on prime-time BBC TV on October 4th 1999 and won instant acclaim. It also won an incredible audience of over 19 million viewers, which put it in the top-spot above the soap-operas and other… stuff that people watch.

Dave had been given the entire series on VHS tape (one tape per episode, how 20th century). I stole them from his office without his permission, took them home, and watched them all in one go. I then did a really evil and stupid thing that I totally wouldn’t do today: early in October 1999, I posted a lengthy review of the entire series (albeit with a few fair spoiler warnings) online, specifically at the dinosaur mailing list (my primary internet stomping ground at the time). I was mostly really positive, describing it in conclusion as “a must see, with some excellent content”.

Caption: important sources for the WWD backstory. At left, Vol 3, Number 4 of the Dinosaur Society (UK) Quarterly; at right, Martill & Naish (2000). I’m not sure that enough has been written about the impact of WWD on public opinion and education (… or has it?); both publications should be good places to start if such a project were to occur.

And indeed, WWD would later win a slew of awards and – despite complaints from palaeontologists and others about the boldness of its claims and speculative nature of its storylines – become a ridiculous success. Everyone involved benefitted from their association with it, and such was its value as what we’d today term a science outreach project that the more public-facing of its consultants used it, understandably, to promote themselves and their host institutions. Dave somehow managed to get a few glossy photos showing himself next to the sorry lifeless corpse of the immense male ‘Ornithocheirus’* while holding a University of Portsmouth promotional placard. I don’t recall seeing this photo used in print anywhere, but maybe it was.

Caption: a sorry end to a noble life. The WWD ‘Ornithocheirus’, folded up in a crate at the University of Portsmouth. Its busted limbs and broken teeth are evidence of a tough few final months…. Image: Darren Naish.

* I put Ornithocheirus in quotes because the animal featuring in the series is not based on Ornithocheirus proper, but on the Brazilian animal Tropeognathus. WWD followed the view of one of its consultants (Dr David Unwin) that these pterosaurs are synonymous, their variation in crest presence being due to sexual dimorphism. We discussed this matter in the book Walking With Dinosaurs: the Evidence (Martill & Naish 2000).

On consultants. My emphasis throughout these two articles (part 1 here) has very much obviously been on Dave Martill’s role, and – as we’ve seen – Dave was the first expert to be involved and thus arguably the most influential of them all. But Dave was only one of a list of consultants. As noted in the ‘making of’ documentary and in the book that Dave and I published (Martill & Naish 2000), the others included palaeobiologist and sauropod expert Professor Kent Stevens, theropod expert Dr Thomas R. Holtz, ornithischian expert Dr David Norman, pterosaur expert Dr David Unwin and dinosaur and marine reptile expert Dr Ken Carpenter. Professor Michael Benton – whose published work has spanned fossils pertaining to what seems like the entire history of life – also had a role. I emphasise that I’m not fairly describing the input of any of these workers, only because I don’t know the story from their side of things.

Caption: it’s well known among dinosaur experts that WWD’s diplodocids owe their mostly horizontal necks to then new research published by Stevens & Parrish (1999), later challenged by Taylor et al. (2009). Image: (c) WWD/BBC.

While WWD – like many palaeodocumentaries – was able to state that it had worked extensively with its experts throughout its development, I heard more than once that what actually happened was that said experts were only wheeled in late in the day, by which time it was mostly too late to change anything that needed it.

I have no idea what really happened, but I will say that this is unlikely to be entirely accurate. When I worked at Impossible in 2007, it was standard practise to have a technical expert on hand permanently throughout the development and production of a project, and I believe also that at least one such expert – palaeoichnologist Dr Jo Wright – played exactly this role during WWD’s production. I will also add here my opinion that palaeodocumentaries simply must – if they want to be at all good – have technically qualified staff on hand throughout the entirety of their production, since that seems to be only way in which film-makers get the steer… or series of kicks… they need every step of the way.

Props and their fate. Having perhaps vacillated slightly over Dave’s ‘importance’ in the hierarchy of consultants, I need to backtrack a bit, since one thing that Dave excelled at was getting hold of the (apparently now unwanted) physical props constructed for the series. Tim Haines basically let Dave have a whole bunch of them for use in teaching. Thus the University of Portsmouth was briefly home to the adult Ophthalmosaurus, the giant ‘Ornithocheirus’ and the comically enormous head of the temnospondyl Koolasuchus. As you can see from my photos here, we had all of these models kicking around in our department at one time or another.

Caption: my only photo of the Koolasuchus head, here stowed in a corner of Dave’s office. Wear and tear is obvious around its edges. Image: Darren Naish.

The Ophthalmosaurus had literally been towed around in seawater and was in a sorry state, its foam and latex exterior swollen and torn and the absorbed water making it heavier than it originally was (it contained a ton of wiring and was heavy anyway). Dave collected it in one of the university minibuses (with official permission, I’m sure), and a bunch of us then pulled it onto a wooden crate and fought and struggled with the bastard thing to get it up the ramp, into the departmental lift and to our base on the fourth floor. The good news is that a deal was made with Dinosaur Isle Museum on the Isle of Wight. They had space for it and the museum’s Dr Lorna Steel (like me, a graduate of the University of Portsmouth and one of my former office-mates) repaired, renovated and repainted it, and today it’s on show to the public.

Caption: the WWD Ophthalmosaurus in our department, a carefully placed curtain disguising the opening on its belly which revealed its umbilical wiring. Image: Stig Walsh.

Caption: the WWD Ophthalmosaurus model, today on display at Dinosaur Isle, Sandown, Isle of Wight. The heteromorph ammonites that accompany it in the display were made specially from plastic piping and look great. Image: Darren Naish.

I’m not quite so sure on what happened to the other models. The Koolasuchus appears to have been sold off cheap; the ‘Ornithocheirus’ was on display at Dinosaur Isle for a time (I remember it being stood in a quadrupedal pose, though I don’t seem to have any photos of it, for shame) but it also ended up being sold. At least some of the models are today on show at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and ended up there due to an association between the museum and Crawley Creatures, the company that made them.

WWD the Exhibition at York. The success of WWD resulted not just in follow-up TV shows but also in exhibits and travelling exhibitions. By the summer of 2000 – only a few months after WWD had shown on TV – a ‘Walking With Dinosaurs: the Exhibition’ was up and ready for viewing at the Yorkshire Museum in York. Dave was invited to attend the official opening in the July of 2000, and I cheekily tagged along. We were hosted by the exhibition’s organiser, Dr Phil Manning, who I believe was keeper of geology there at the time.

Caption: Dave Martill (at left) and Phil Manning at the WWD exhibition at the Yorkshire Museum. In the background, we can see the cynodont model at extreme left (effectively just as a silhouette) and a dromaeosaur maquette (Utahraptor?) at right. Image: Darren Naish.

The exhibition featured a very nice assortment of dinosaur exhibits, most or all having some direct connection to WWD. I only recall (thanks to the photos I took and still have) a Plateosaurus skeleton, a cast of the skull of ‘Stan’ the T. rex, an over-sized Coelophysis model (made by the very excellent Peter Minister and very competently painted with the WWD livery) and various props. I don’t remember looking at them, but one of my photos shows a cynodont model and what looks like a dromaeosaur maquette. An article reviewing the exhibition (Maddra 2001) notes that WWD’s ‘Ornithocheirus’ and Eustreptospondylus were on display too, as were replica fossils of Liopleurodon, Compsognathus, Archaeopteryx and Ankylosaurus.

Caption: large Coelophysis model on display in the WWD exhibition, photographed at the Yorkshire Museum in 2000. Image: Darren Naish.

A video and TV monitor played a ‘making of’ documentary that you could watch if you wanted. The voiceover was provided by Stephen Fry who had been able to insert a few home-made quips of his own (I remember in particular a reference to the Plasticine Era when describing the noble art of real-world model making). I also remember that the text for the exhibition’s information panels included a few indications here and there that it had been based on material included in Martill & Naish (2000), which is perhaps to be expected.

The day prior to our visit was the official opening, and the guest of honour had been Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Phil (Manning!) told us that the Duke had – when in front of a part of the exhibition mentioning plesiosaurs – told him at one point that “they’re still alive, you know”, this presumably being a reference to the Loch Ness Monster. It’s well known among those interested in this sort of thing that the royal family had a connection of sorts with the Loch Ness Monster, in part due to Peter Scott’s efforts to get HRH Queen Elizabeth II made the patron of a serious effort to scientifically recognise and conserve the monster. For more on that story see my articles here, here and here.

Caption: Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, was - at some level - involved in the (ultimately doomed and unsuccessful) attempt of the 1970s to have the Loch Ness Monster recognised as a real animal. See my article here for more, as well as Williams (2015).

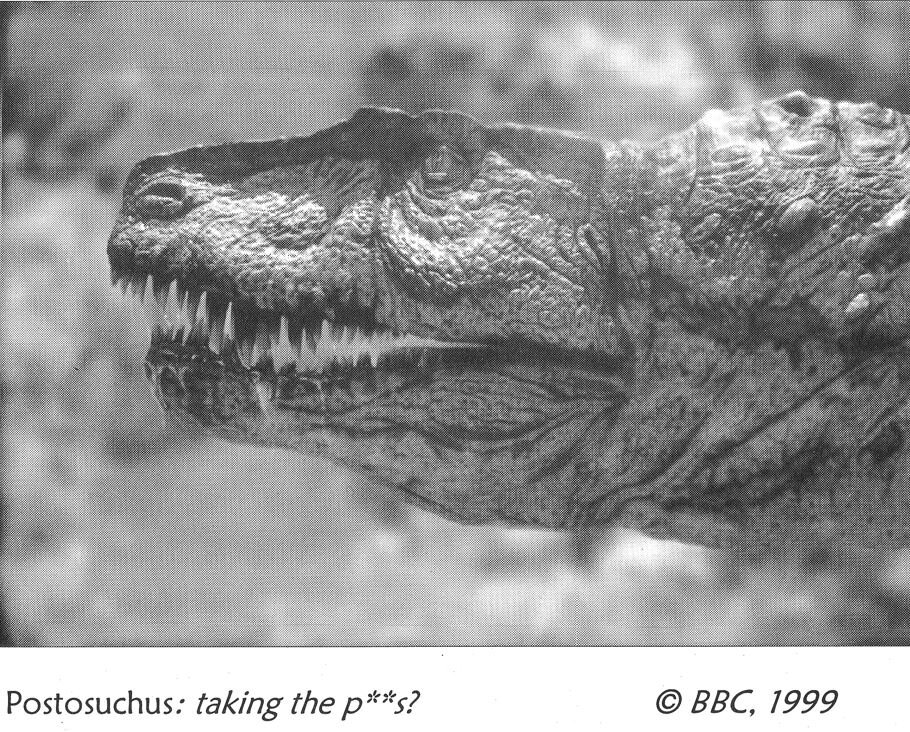

WWD the aftermath. Most of us who remember WWD’s screening in 1999 recall the protestations of certain palaeontologists, some of whom pointed to supposed technical errors (the Natural History Museum’s Angela Milner very much disliked the urinating Postosuchus), others of whom objected to the idea that speculations about the behaviour of Mesozoic animals should be presented amid a ‘factual’ narrative where the audience were led to believe that the relevant things were definitively established.

Caption: a textbook caption. From Haines (2000).

One of the broadsheet newspapers (perhaps The Sunday Telegraph… UPDATE: no, The Guardian) featured a double-page spread in which criticisms from dinosaur specialist Dr Paul Barrett were pitted ‘against’ a pro-WWD stance given by series consultant Mike Benton. A… nameless person* had described the scientific consultants of such TV shows as prostitutes: here was Mike’s chance to note that, indeed, he could be found most evenings in an alluring red dress while leaning against a lamp-post and that his rates were reasonable. We had this two-piece article on the departmental wall for a while, and I know other universities – cough Bristol – did too.

* My apologies for previously attributing this statement to the wrong person.

Caption: any article that includes the term ‘J’accuse’ in the title is – ordinarily – a good read. This is the introduction from Haines (2000).

It should be noted, however, that sceptical or dismissive voices were essentially in the minority in the months and years following WWD’s screening. Of the numerous articles and other publications that appeared in 1999 and beyond, most were of the wide-eyed “I walked with a dinosaur!” type (Gates 1999, Helton 1999, Helton & Haines 1999, Haines 2000, Horley 2001, Stevens 2000) and cynicism was absent. Extremely spirited responses to nay-sayers were provided by Liston (2000) and Haines (2000); both are really interesting reading in view of what’s happened since. And despite complaints about various of the creative decisions and technical inaccuracies (read on…), the series is mostly remembered as a force for good: it showed that CG animals could be brought to life for the small screen after all, and it also portrayed its animals as animals. It owed more to the natural history genre than to the fantasy or sci-fi schema which otherwise dominates popular depictions of ancient life.

Caption: BBC Wildlife vol. 17, no 10 (the October 1999 issue), a rich source of behind-the-scenes WWD material. Try as I might, I’ve been unable to get a good reproduction of the cover that isn’t skewed in some way.

I was ultimately to benefit from my association with Dave Martill and the success of WWD, firstly because I got to co-author the 2000 book Walking With Dinosaurs: the Evidence (Martill & Naish 2000) and thus make inroads into the world of publishing, and secondly because I ended up landing a job at Impossible Pictures and ultimately with Dinosaurs in the Wild in 2017.

Various specifics of the series – the neck posture of the diplodocids shown in episode 2, the massively over-sized Liopleurodon of episode 3, the specific name and inferred sexual dimorphism given to the pterosaur of episode 4 and so on – have been the source of extensive post-1999 discussion and debate. I have often seen palaeontologists frame these issues as liberties or fictions made by the film-makers. But it’s crucial to note that Tim Haines and his colleagues weren’t to blame for these decisions. They had, on the contrary, followed the advice they’d been given by their consultants. And much as I’d like to elaborate on that point, I can’t do so now as it would involve adding thousands of words to this already over-long two-part article.

Caption: WWD and its makers have received some modicum of flak for ‘super-sizing’ the Jurassic pliosaur Liopleurodon. Fact is though, they didn’t super-size it: rather, one of their consultants pushed the extreme size as a scientifically supported, justifiable extrapolation (Naish et al. 2001), and they followed it. Image: (c) WWD/BBC.

To return to a point made right at the start of part 1, I think it’s fair to say that a good number of young and youngish people interested in prehistoric animals today partly owe their interest in palaeontology and the history of life to WWD and remember the series in a very positive way. Such was very much evident to me personally when I arranged to have Tim Haines speak at TetZooCon in 2019 (more on that here): the audience reaction was phenomenal!

And that about wraps things up. I hope you enjoyed this nostalgic look back at events of the distant past, and I hope that my recollections weren’t too tenuous or uninteresting. Thanks for reading.

For other TetZoo articles on some of the topics mentioned here, see…

Sauropod dinosaurs held their necks in high, raised postures, May 2009

The changing life appearance of dinosaurs, September 2014

The Unique and Efficient 4-Flipper Locomotion of Plesiosaurs, August 2017

Dinosaurs in the Wild: An Inside View, July 2018

The Last Day of Dinosaurs in the Wild, September 2018

The Life Appearance of Sauropod Dinosaurs, January 2019

The Sixth TetZooCon, October 2019

The Netflix Series Alien Worlds, January 2021

Help support this blog and my other projects at patreon: go here!

Refs - -

Gates, P. 1999. Uprooting the past. BBC Wildlife 17 (10), 38-44.

Haines, T. 2000. J’accuse: Tim Haines. The Dinosaur Society UK Quarterly Magazine 3 (4), 8-9.

Helton, D. 1999. The giant resurrection. BBC Wildlife 17 (10), 16-24.

Helton, D. & Haines, T. 1999. Stars from the past. BBC Wildlife 17 (10), 26-36.

Horley, D. 2001. Making of ‘Walking With Dinosaurs’. DinoPress 5, 4-17.

Liston, J. 1999. Tiptoeing amongst the egos. The Dinosaur Society UK Quarterly Magazine 3 (4), 3.

Maddra. R. 2001. ‘Walking With Dinosaurs – the Exhibition’ at the Yorkshire Museum, York. The Quarterly Journal of the Dinosaur Society 4 (2), 21.

Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. 2000. Walking With Dinosaurs: The Evidence. BBC Worldwide, London.

Naish, D., Noe, L. F. & Martill, D. M. 2001. Giant pliosaurs and the mysterious ‘Megapleurodon’. Dino Press 4, 98-103.

Stevens, K. 2000. I walked with a dinosaur! The Dinosaur Society UK Quarterly Magazine 3 (4), 10-11.

Stevens, K. A. & Parrish, J. M. 1999. Neck posture and feeding habits of two Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs. Science 284, 798-800.

Williams, G. 2015. A Monstrous Commotion: the Mysteries of Loch Ness. Orion Books, London.