Regular readers of Tet Zoo – and that group includes, by definition, people whose interests are similar to mine, hello! – will be aware of my affinity for what we now term Speculative Zoology, or Spec Zoo. That’s a topic that’s been covered here (and in previous incarnations of the blog) quite a few times, as you can see from the links below. And within that field, one person above all others has been foundational and worthy of repeated visitation.

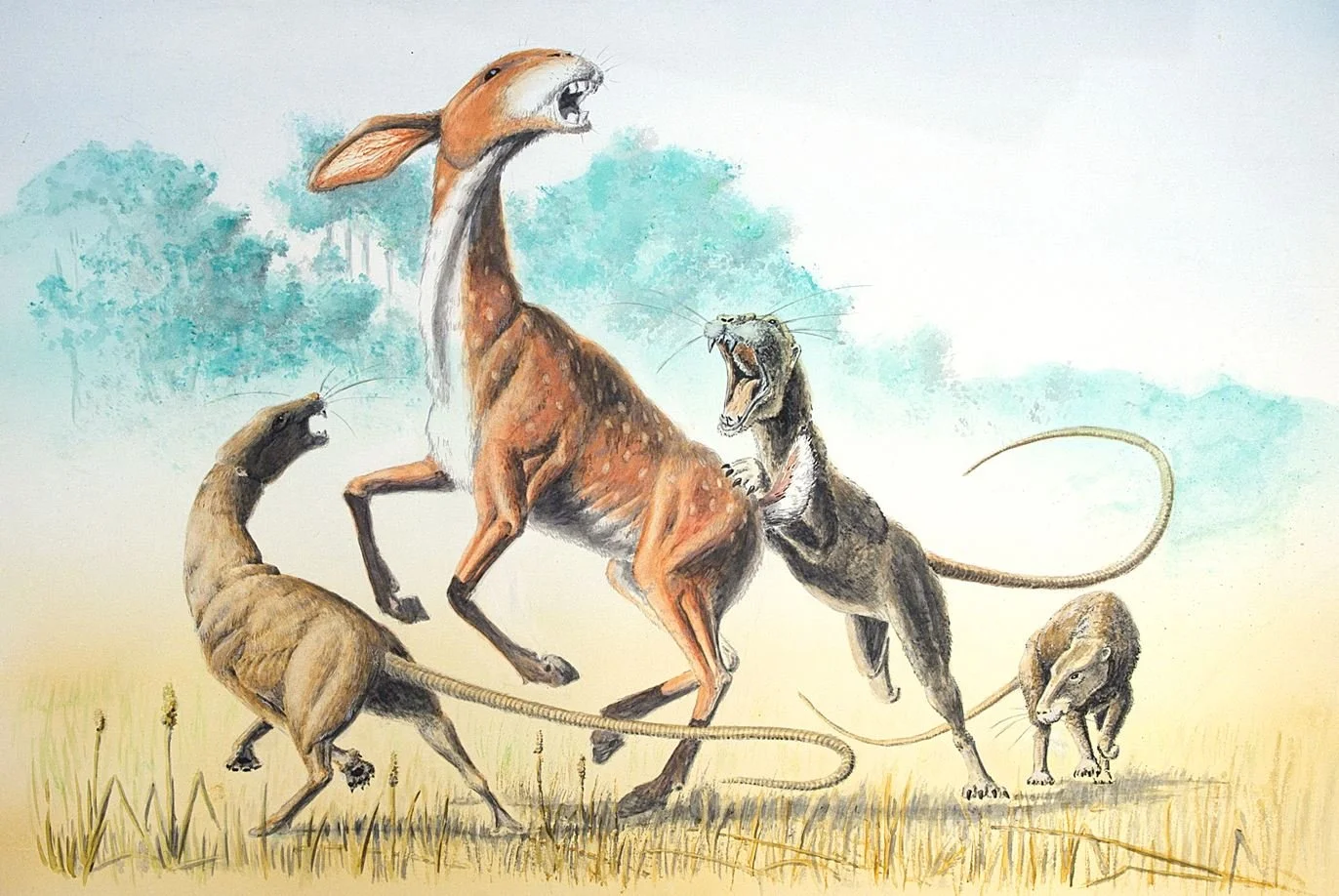

Caption: in a scene from the future world of After Man, giant predatory rats harry a rabbuck. If you know the look of the animals in the final book, note how different these versions are… Dougal Dixon’s original concepts were, in cases, not exactly like the final animals ultimately illustrated by other artists. Image: (c) Dougal Dixon, used with permission.

I refer, of course, to British writer, author, visionary, artist and designer Dougal Dixon, generally and correctly regarded as the ‘father’ of modern speculative zoology… even though he denies this accolade in his own writings (Dixon 2021). Exactly where speculative zoology (and its more inclusive parent, speculative biology) fits in terms of genre has been relatively under-analysed but the fact that it involves an intersection of natural history writing, palaeontological knowledge, evolutionary theorising, imagination and artistry, and might also require the trappings of science fiction (Naish 2014, Thomann 2024) requires that relatively few have indulged in it.

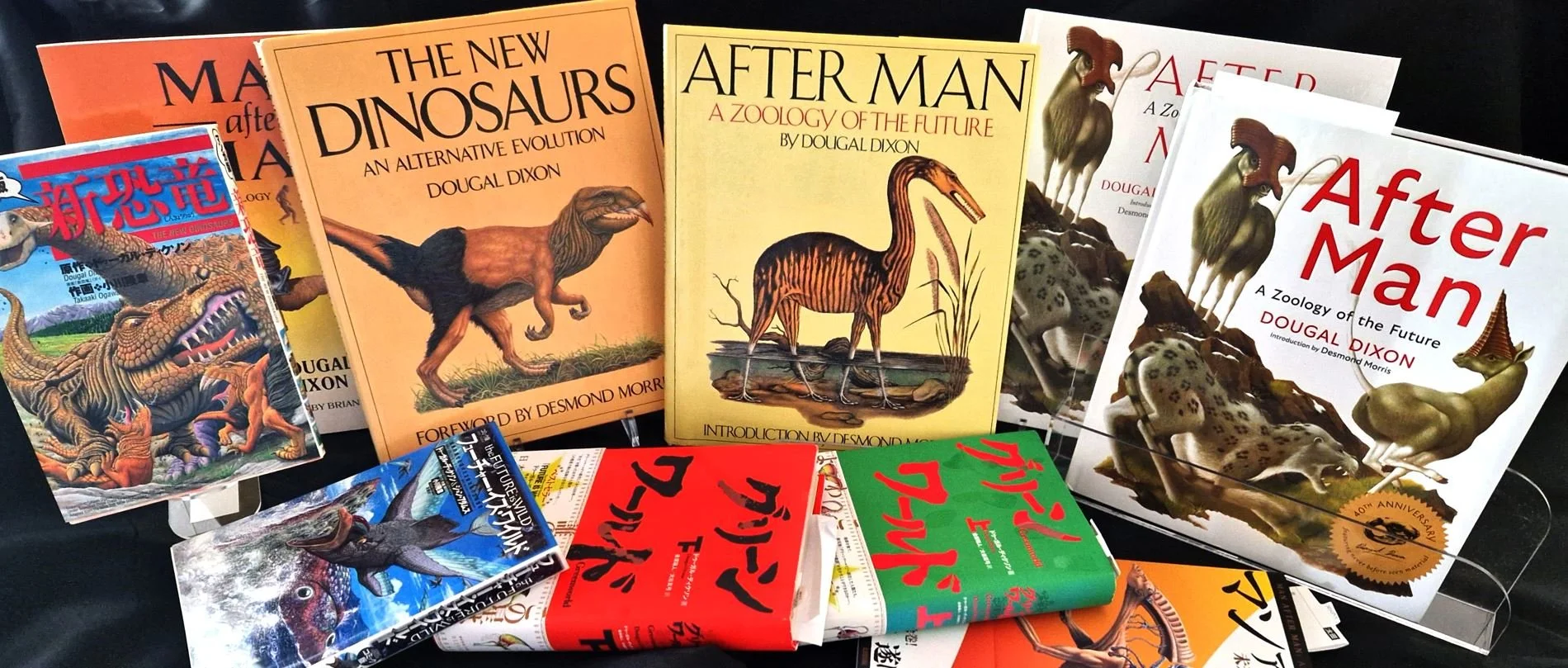

Caption: a selection of Dougal Dixon Spec Zoo books in the Tet Zoo Towers library. The manga The New Dinosaurs and The Future is Wild volumes visible at left are especially hard to get here in the UK. Image: Darren Naish.

Dougal has been the go-to person on speculative zoology ever since the 1981 publication of his famous, beautifully illustrated and extraordinarily successful book After Man (Dixon 1981). Therein, we explore the biogeographical realms of our planet 50 million years in the future: an Earth where the continents have moved, many modern animal groups have disappeared, where large flightless bats inhabit islands, and where rabbits, rats, corvids and mongooses have given rise to a new assemblage of megafauna that also includes novel pigs, antelopes and marsupials. Giant swimming rodents, flightless auks and cetacean-like descendants of penguins inhabit the oceans (Dixon 1981).

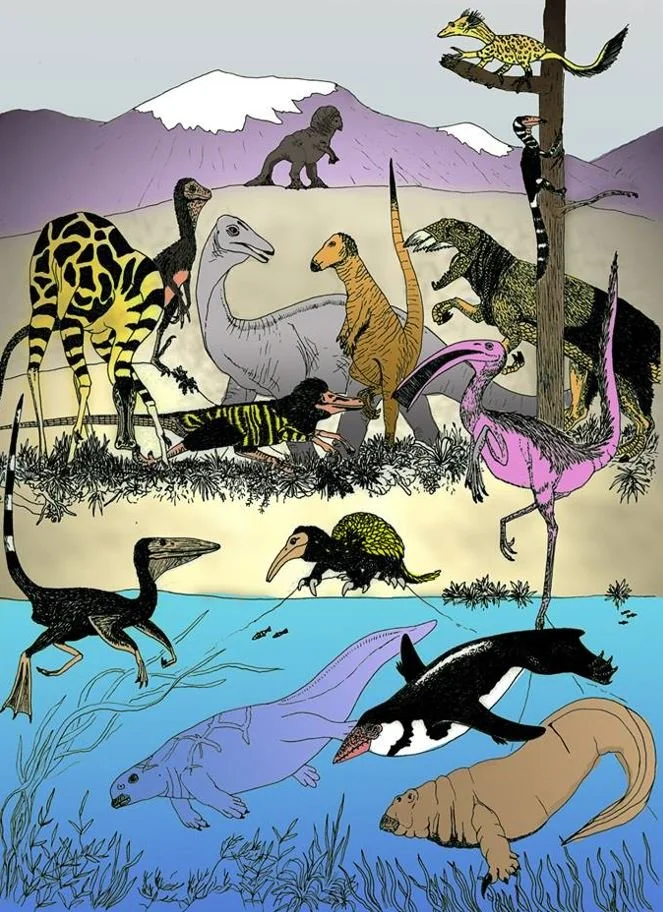

Caption: there’s a lot of After Man fan-art out there, and I’ve created a bit of it myself over the years. This image (created for a Fortean Times article on speculative zoology) shows a Giantala (spotted animal at left), Zarander (tusked and trunked, lower left), a giant raboon (the maned biped), Gigantelope (far right) and (in the tree) a Slobber. I misunderstood the relative sizes of certain of these animals when creating this image and they’re not to scale. Image: Darren Naish, colouring by Rebecca Groom.

Published in multiple languages and countries worldwide, After Man was – and in ways still is – nothing short of a sensation, resulting in more than one dedicated TV show, a travelling exhibition featuring life-sized animatronics, and a worldwide following of fans and aficionados. After Man didn’t merely showcase Dougal’s ideas: the animals – all of them – originated via his own copious drawings and paintings, a fact not as well known as it should be given that the final art featured throughout the book is by others, among them Diz Wallis and Philip Hood.

After Man needed a follow-up and this was provided later in the decade by The New Dinosaurs (Dixon 1988), a book that told the story of a parallel Earth where the end-Cretaceous extinction event never occurred. Again, Dougal designed (and drew) the initial versions of the creatures, while the final art is by Amanda Barlow, Andy Farmer, Philip Hood, Denys Ovenden and several others. If you know British natural history books of the relevant era, some of these names will be familiar. A third volume – Man After Man (Dixon 1990) – appeared soon after, this one being a fantastic look at a speculative future for the descendants of humanity.

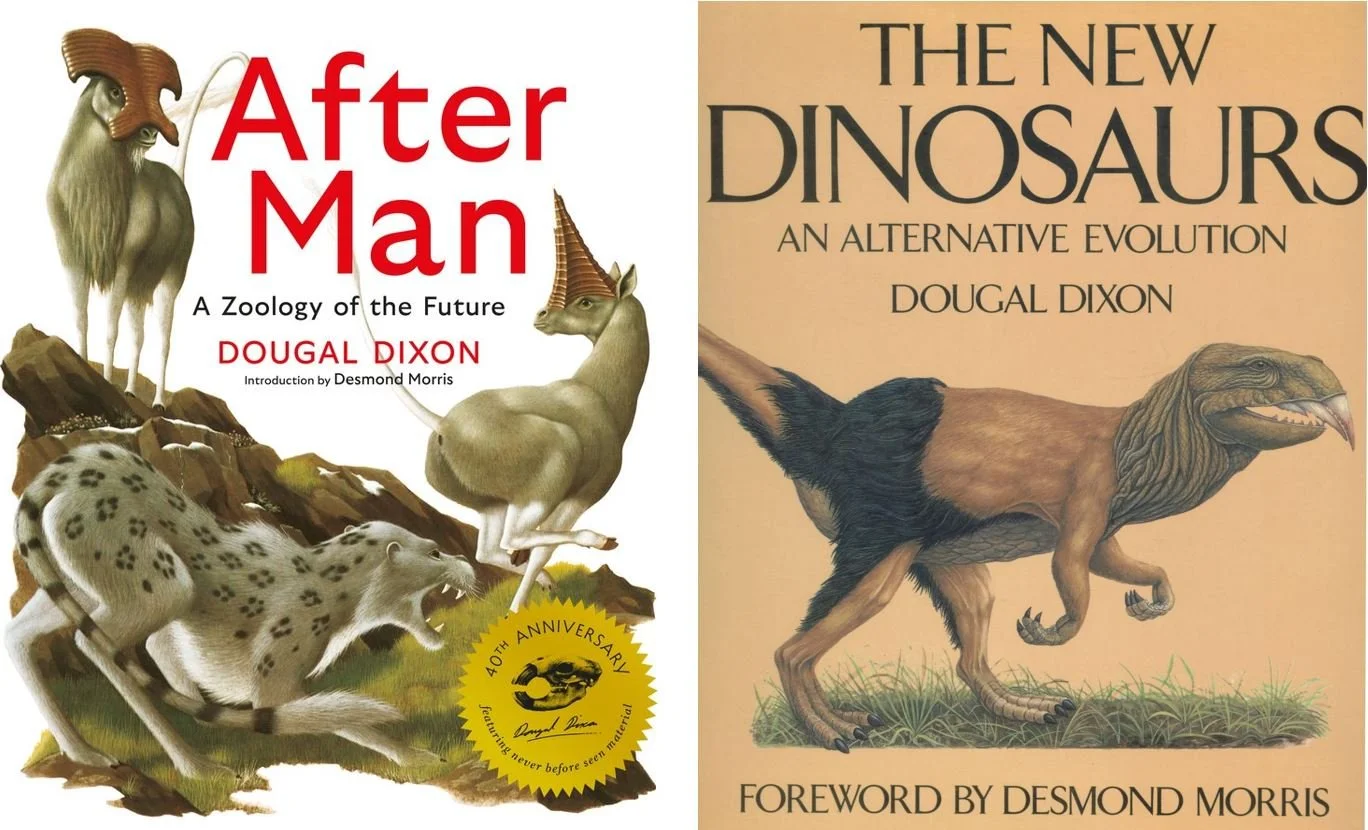

Caption: After Man has had several different covers over the years, and here’s what the 2021 40th Anniversary version looks like. Buy it here from Breakdown Press. After Man might be back in print… what about 1988’s The New Dinosaurs? Well…

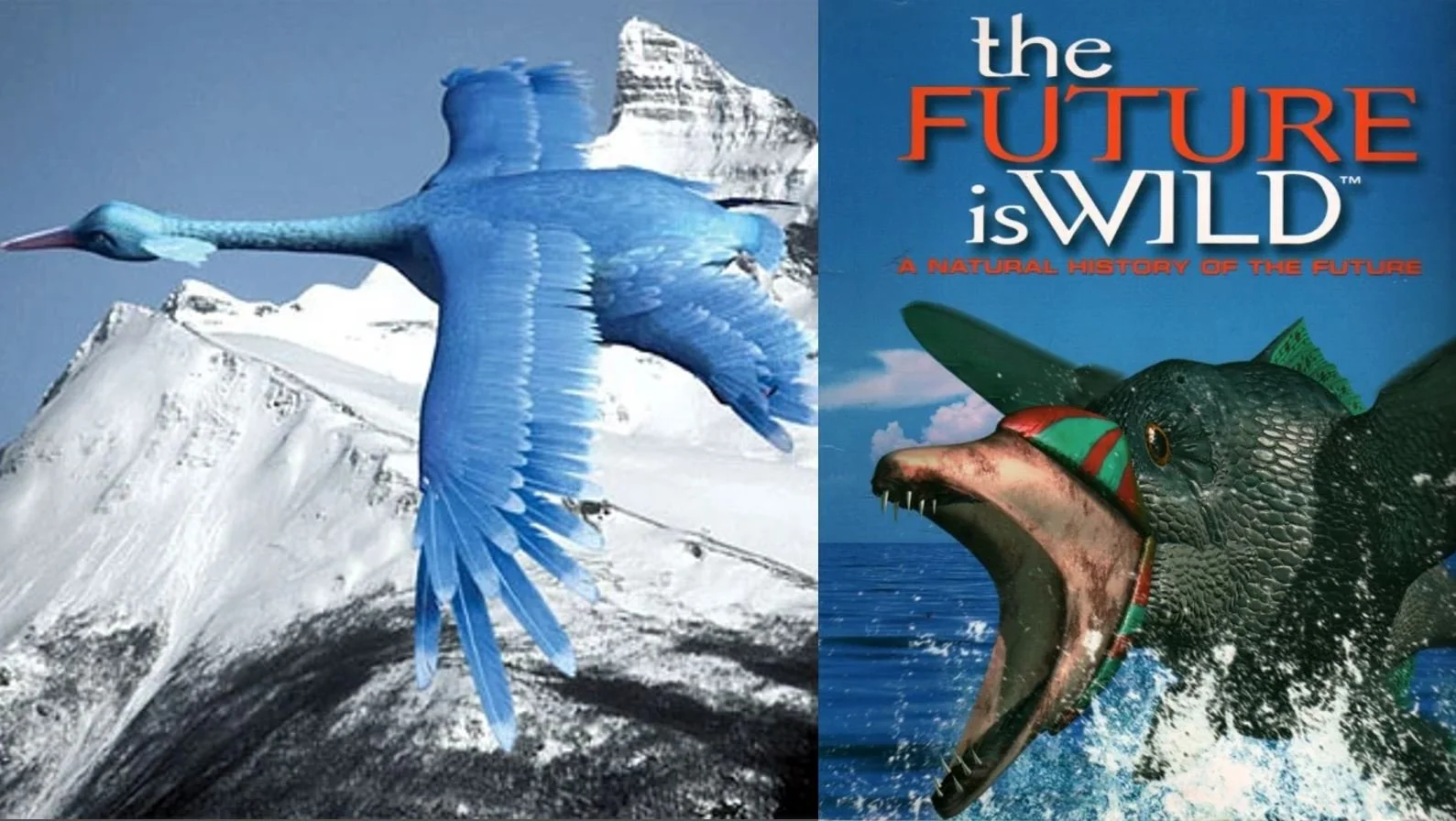

Moving to the 21st century, Dougal was also involved in the TV series The Future Is Wild and coauthored the accompanying book (Dixon & Adams 2004). And while the After trilogy might be… well, a trilogy… was this ever the intention? Evidently not, because a project connected to After Man – Greenworld – came to fruition in the 2000s, though has (so far) only seen publication in Japan (Dixon 2010). More on that matter below (and see the relevant section on Dougal’s website here).

Dougal was born in Scotland but lives in Dorset in southern England, and thus in close proximity to me. We’ve met on numerous occasions (in recent years Dougal has been a regular attendee of TetZooCon), and I’ve rarely failed to pester him with questions about After Man and his various other projects. Back in August 2013, I opted to take advantage of this situation, and Dougal very kindly agreed to be interviewed exclusively for Tet Zoo. As you’ll see below, we covered the back-story to After Man, discussed the inspirations behind certain of his creatures and the way the accompanying artwork came to be, and also spoke about projects that were, at the time, not well known in Europe or the Americas. That interview was published in 2014 (the original can be seen here at wayback machine)… a lot has happened since.

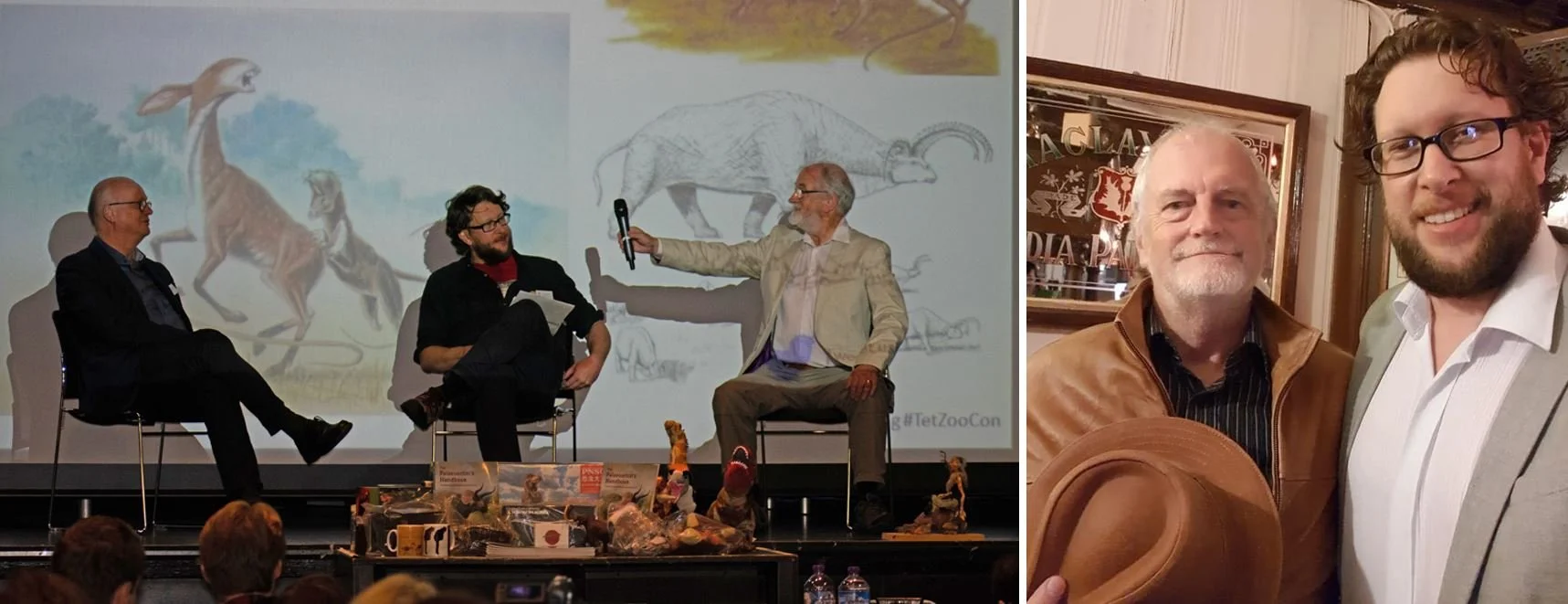

Caption: I’ve met Dougal Dixon many times now and he’s spoken and presented at my TetZooCon events a few times. At left, here’s (left to right) Gert van Dijk (of Furahan Biology and Allied Matters), Darren Naish, Dougal Dixon. At right, Dougal and myself in London for the 2018 After Man event.

After Man in the 21st century. After Man saw republication via Breakdown Press in 2018 (Dixon 2018) and here’s where it became clear just how much ‘backstory’ material Dougal still owned. At a launch event hosted at London’s Conway Hall in the September of 2018, Dougal brought with him the initial pitch document, a huge number of his own initial sketches, a number of 3D models, and much else besides. I was blown away by this and wrote about it here at Tetrapod Zoology; I then cheekily borrowed the aforementioned pitch document and wrote about that too. It was obvious that there was massive public and fan interest in this ‘backstory’ material… would we ever see any of it in print?

Well, 2021 was the 40th anniversary of After Man’s initial publication, so here was the opportunity to republish After Man again. The result (again, from Breakdown Press) was a special, expanded version of the book, with a new Introduction and a substantial ’40 Years of After Man’ section (Dixon 2021). This includes copious ‘backstory’ matter, much in the way of previously unpublished art and imagery, and reproduced press material that publicised the book back in the 80s. The 2014 publication of my interview with Dougal and 2018 article on the initial pitch document played, I think I can say, some minor role in the release of this new version but, whatever, it’s a real treat for fans of Dougal’s work and you must be sure to get a copy for yourself even if you own the 1981 original.

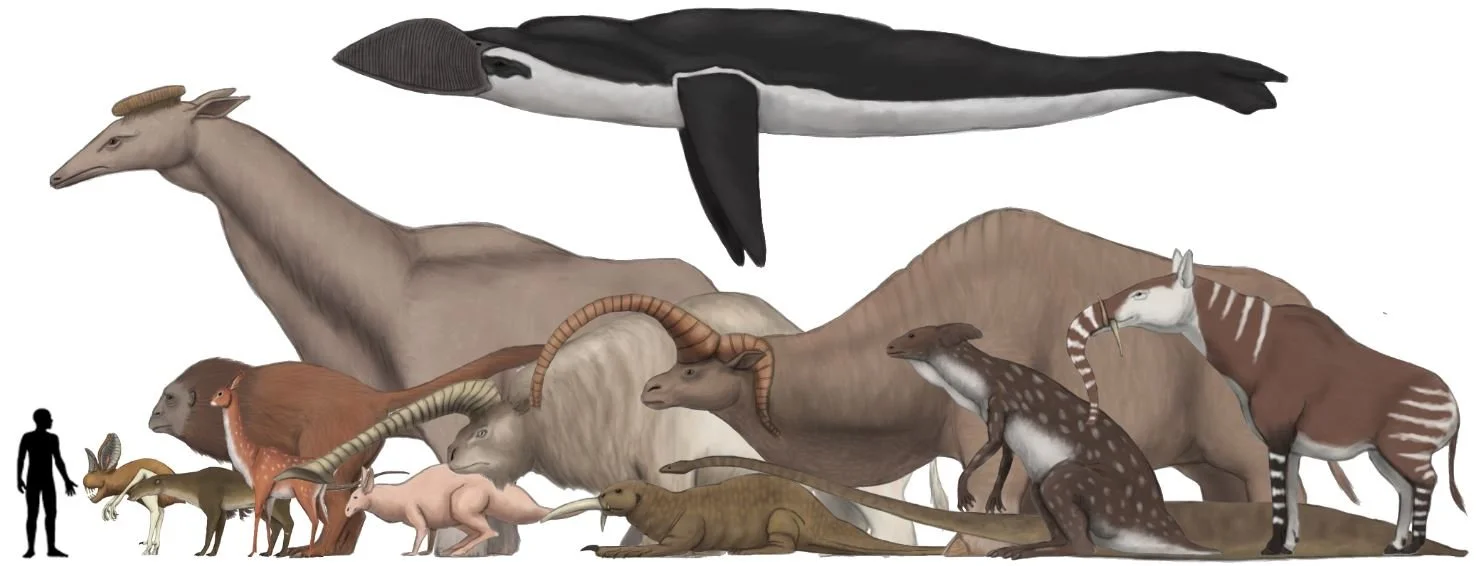

Caption: more After Man fan-art, this time a very nice montage showing some of the book’s larger animals correctly scaled. It’s easy to forget how large some of them are meant to be. Image: Dragonthunders, from here (several other montage images showing scaled Dixonian creatures feature on the same page).

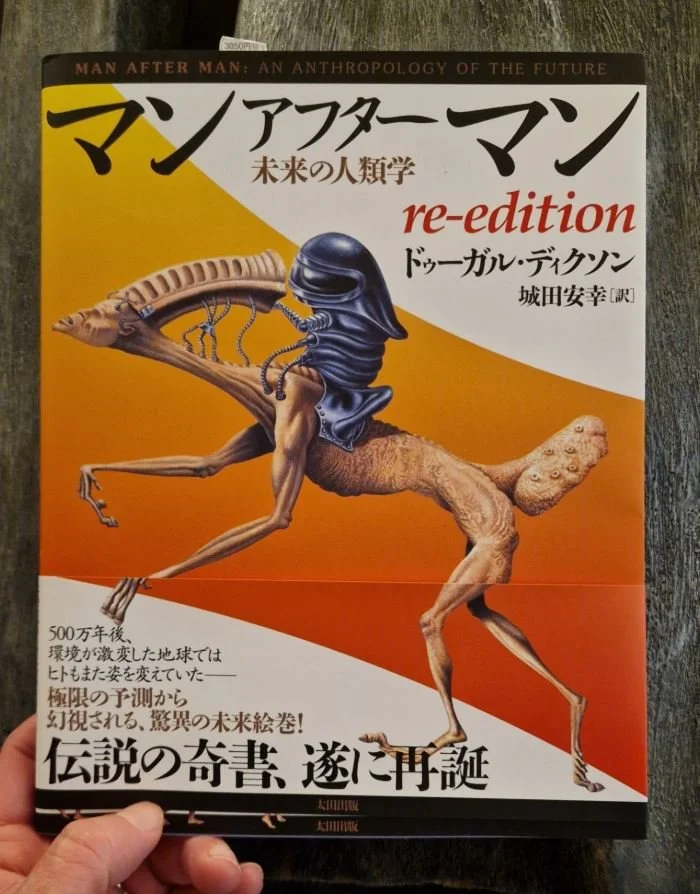

Greenworld still needs an English publisher. At the time of writing, rumours are afoot that new editions of certain others of Dougal’s Spec Zoo works will soon see publication as well. A modified version of Man After Man just saw print in Japanese. Dougal’s two-volume work on an alien world impacted by its human visitors – Greenworld – still needs publication in English and only parts of its complex story have been released outside of Japan so far. Inevitably, the tale of Greenworld – one where a lush, teeming biological paradise is filled with exotic alien organisms of numerous sort – recalls James Cameron’s Pandora of the Avatar franchise (first outed in December 2009), but that’s a coincidence and perhaps shows how alluring we find this vision to be. Greenworld and Avatar both function, of course, as parables of our impact on the natural world, an issue more pressing today than ever.

Caption: front cover of the 2024 Japanese edition of Man After Man. It is much modified relative to the original. Image: Darren Naish.

Anyway, the primary justification for the existence of the article you’re reading now is that I – perpetually frustrated that my old ScienceBlogs and Sci Am material is now unavailable, vandalized or even paywalled – recently decided to revamp and republish the 2014 interview text discussed above. There are a few statements of my own, made in the 2014 version, that I disliked or which are now wrong, so they’ve been modified or now have addenda. Without further ado...

Darren: First of all, do you realise how important and inspirational, how loved and cherished, the ‘After’ trilogy has been?

Dougal: Certainly. I get emails from established, professional people in the world of biology and palaeontology who say that my work inspired them 30 years ago. Some of these people were amateurs or beginners when they read the books.

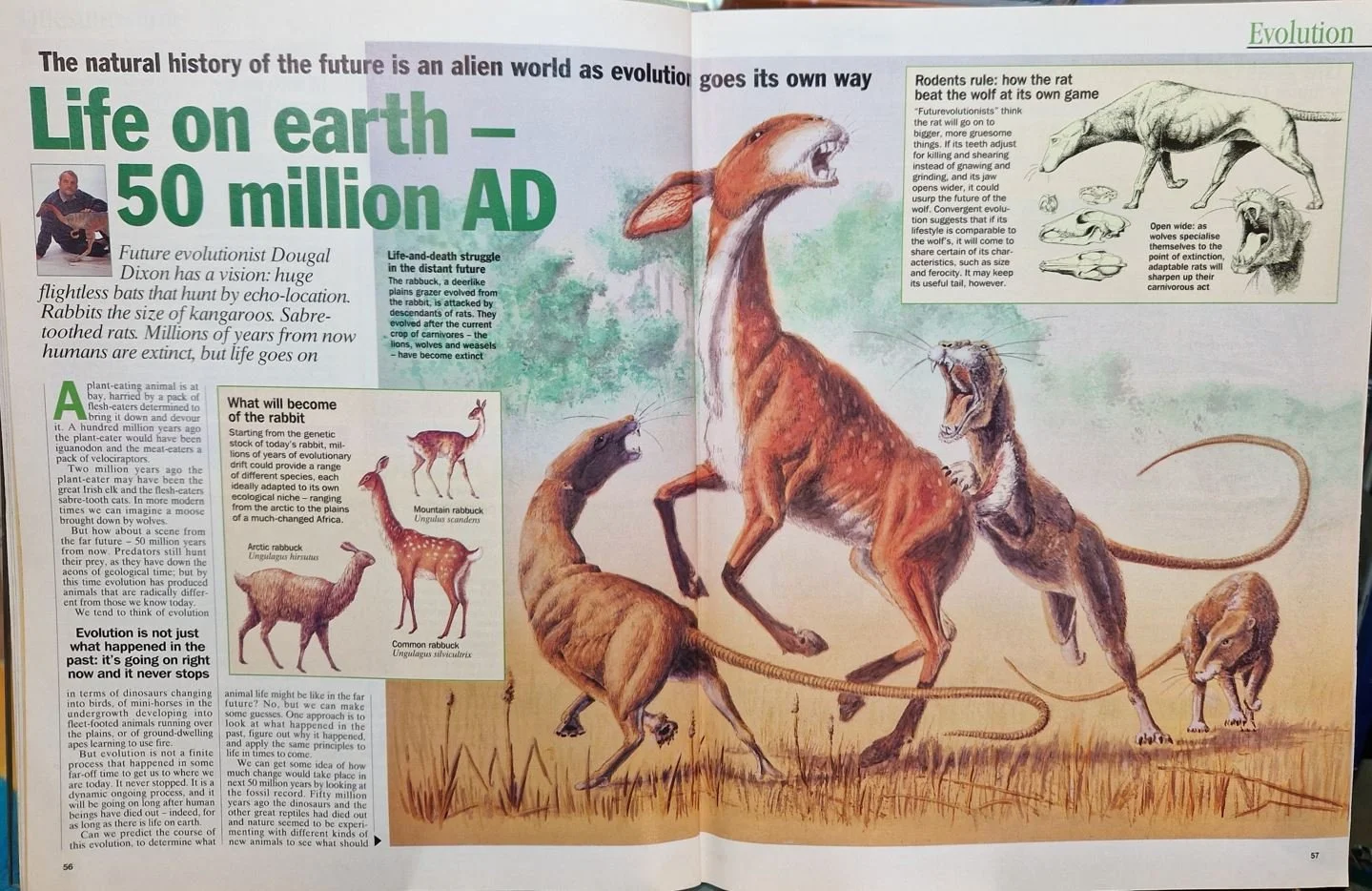

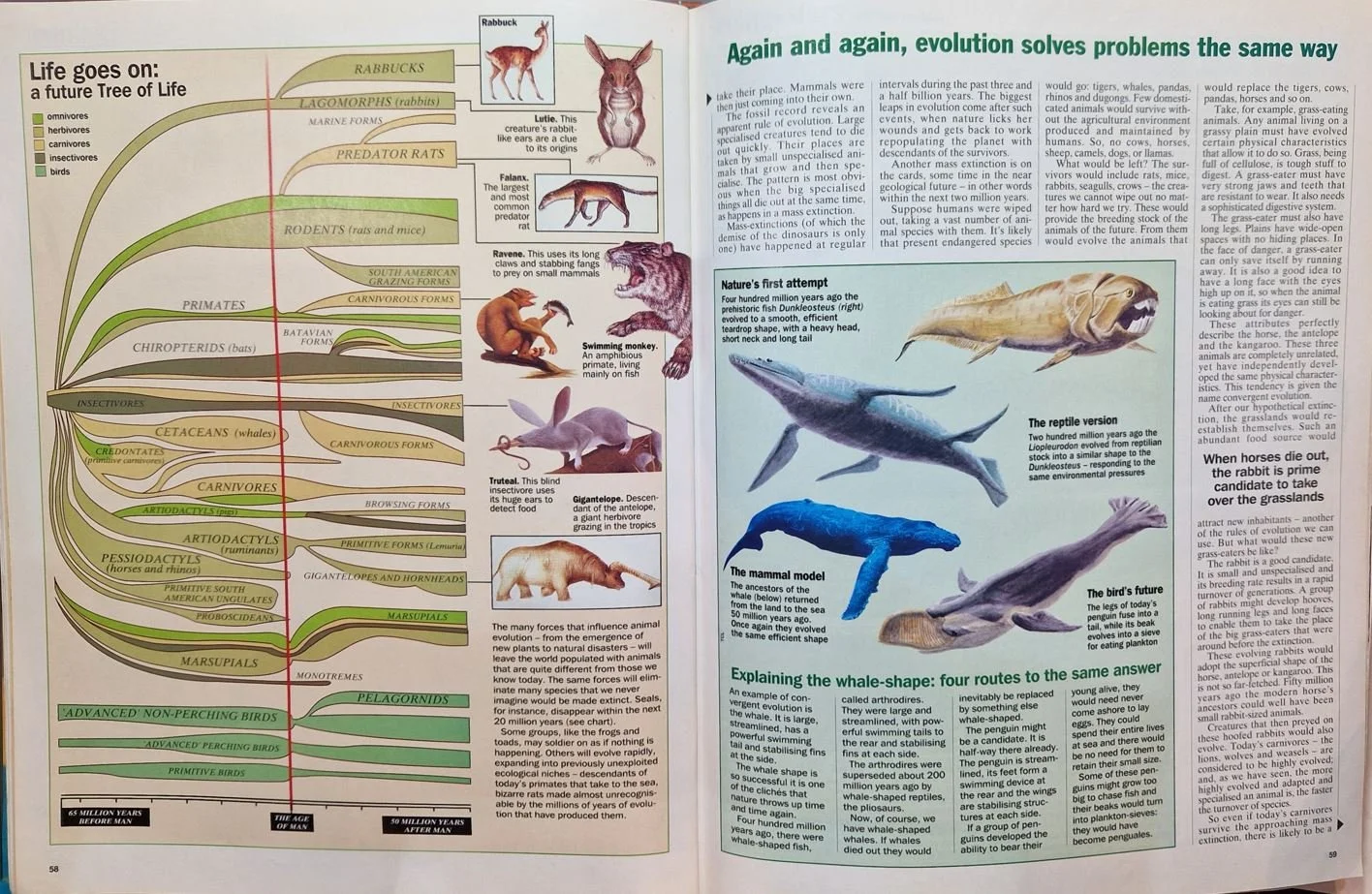

Caption: over the years, numerous magazine articles have rehashed and summarised the main story points of After Man. The 1995 special issue of Focus include this feature on After Man (Anon. 1995), and it was surprising by showing illustrations novel to me at the time, like the predator rat bs rabbuck image.

Caption: the 1995 Focus article also features various images based on those of After Man (like the family tree) or taken from it. That Vortex at right was novel and I haven’t seen it elsewhere. No author is credited for this piece so I have to cite it as ‘Anon. 1995’.

Darren: Do you follow the speculative zoology movement – are you aware of such things as SpecWorld (the Speculative Dinosaur Project) or the future creatures in Primeval?

Dougal: I have of course seen Primeval.

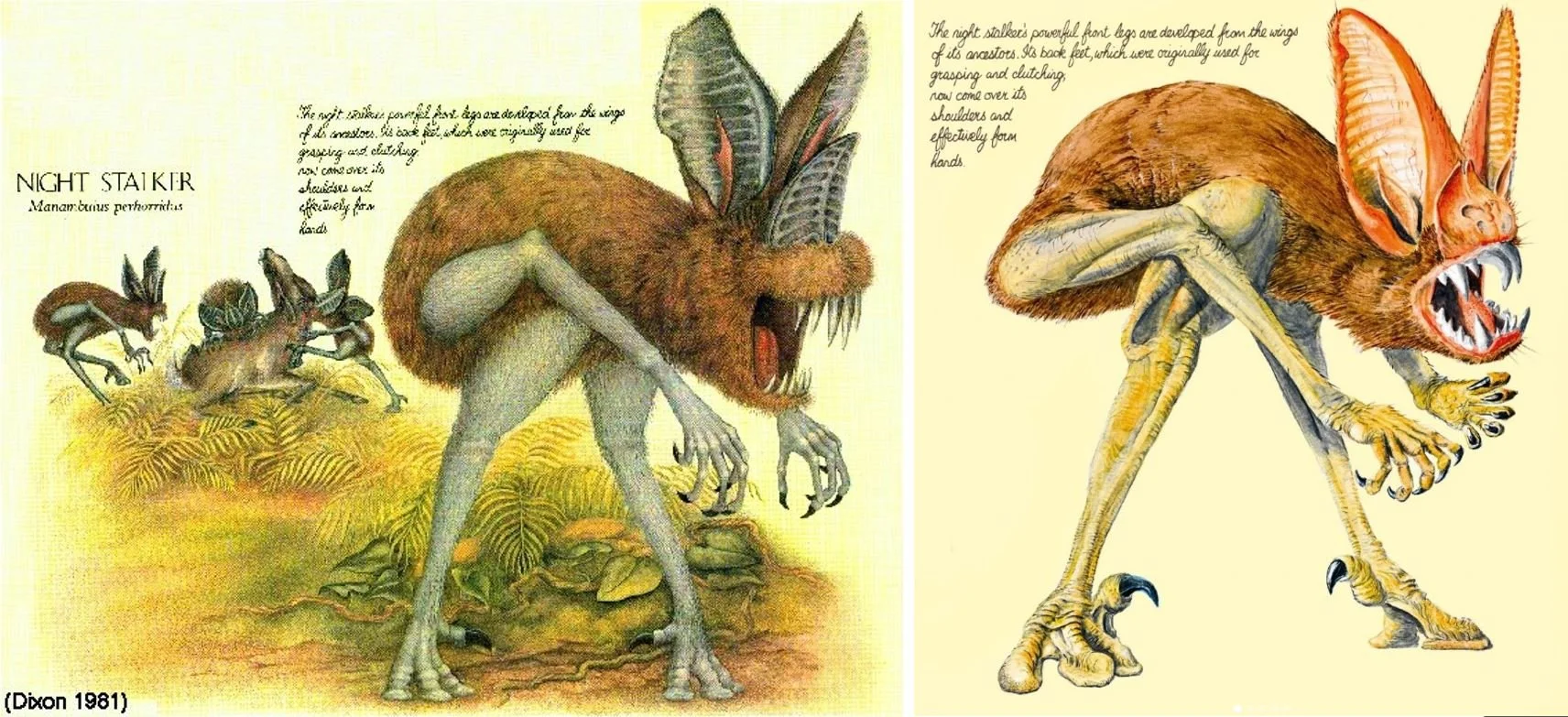

Darren: I always thought the Future Predator was inspired by your flightless bats (especially by the Night stalker of After Man).

Dougal: Oh yes, I’m sure that’s not a coincidence. I’ve been told that Tim Haines has a copy of After Man on his bookshelf.

Darren: Right. I asked him quite a few times about that (I worked at Impossible Pictures for a while a few years back) and he always cleverly evaded me. [UPDATE: while the Future Predator is canonically a bat today, the initial concept art and communications from the Impossible Pictures team show that it wasn’t initially any such thing. Instead, it started life as a vaguer, more reptilian predator. It’s not accurate to claim that it originated as an After Man homage or copy]. Moving on... can you remember (this is going back a long way!) what the original inspiration was for After Man?

Caption: the different editions of After Man now depict more than one version of the Night stalker. At left, the 1981 version; at right, the improved vision from Dixon (2018, 2021). It’s true that views differ on how ‘plausible’ it might be that bats would ever, or could ever, evolve in this direction, but I put it that the Night stalker remains an iconic vision in discussions about speculative bat evolution. Images: Diz Wallis, from Dixon (1981); Dougal Dixon, from Dixon (2018, 2021).

Caption: photo – from the dustkjacket of After Man (Dixon 1981) – showing Dougal with his model of a Night stalker. Image: Duncan McNicol.

Dougal: As a child I was always struck by The Time Machine, by H. G. Wells, in particular by the part at the end where he goes to the far future and everything has changed: there are the giant crabs and so on. I was always artistic as a kid. I remember at the age of 8 or 10 years old, drawing comic strips, and one of them was actually my own retelling of The Time Machine. I had fun creating my own future creatures that had evolved from those of the modern day, featured there in the background. [UPDATE: for a more detailed retelling of these events, with relevant illustrations, see Dixon (2021).]

Darren: [incredulously] You came up with that stuff as a kid?

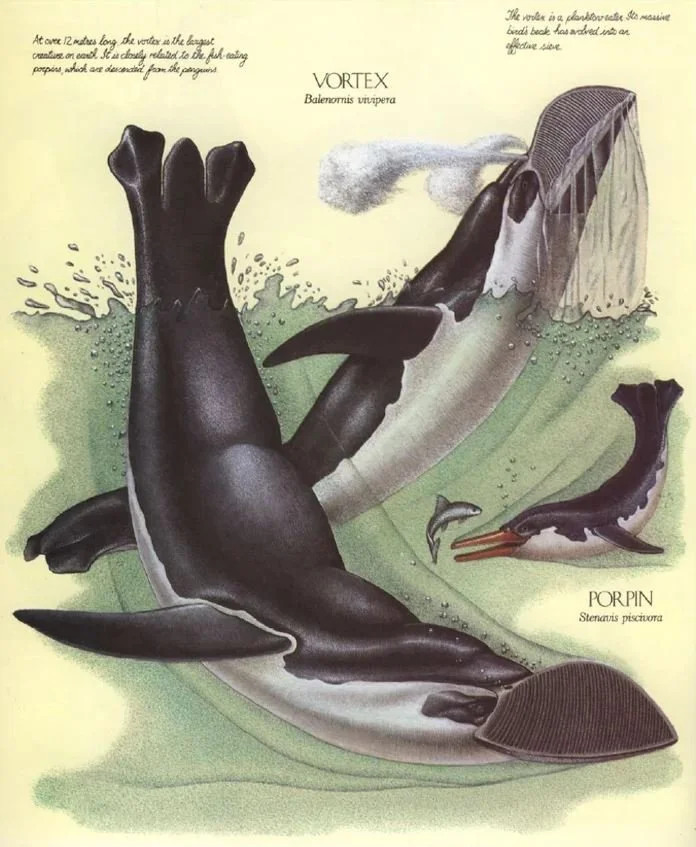

Caption: the giant, flightless, fully aquatic penguins of After Man, namely the mysticete-like Vortex Balenornis vivipera, and dolphin-like Porpin Stenavis piscivora. Image: Diz Wallis, from Dixon (1981).

Dougal: Well, yeah, not that there was any scientific point to it: it was just the background to the story. The next stage really – I was a teenager, so we’re in the 1960s now – would be when I was influenced by the conservationist movement that became important at the time. I remember in particular the ‘Save the tiger’ campaign. I was watching a TV programme about tiger conservation with my Dad, he turned to me and said “Why save the tiger? The tiger will become extinct. Everything becomes extinct, other things evolve”. And I thought – that’s a very unhelpful attitude, but it basically started me on a learning curve about evolution, and I essentially realised that he was right: everything does become extinct, other organisms develop to take their place. And I began to think to myself – just as idle musings – if things do become extinct, what evolves to take their place? Move on now to the late 1970s, I met a friend of mine I hadn’t seen from a long time and he was wearing a ‘Save the Whale’ badge. Well, that sparked off the whole idea again. I thought to myself: suppose the whale does become extinct, what might evolve to take its place? That, of course, is where the whole idea of the giant, whale-like penguins of After Man came from.

A couple of weeks later, I thought… I could use this. I could devise a popular-level book on evolution, but a book that did something quite different. Other popular-level books used evolution to tell the story of the past, but nobody had taken the whole process – the observable trends – and projected them into the future. I thought: I could do this. At this time, I was working in publishing – I was involved in encyclopedias – and I knew how to present a crazy idea to a publisher with a likelihood of being taken seriously. So I decided to create illustrated spreads, dummy text and so on… I took the idea to publishers the next time I was in London, and the rest is history.

Caption: one of several pages from the original BOOK PLAN for After Man, featured here at Tet Zoo but also featured in Dixon (2021). Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Darren: Obviously the concept of After Man was a great idea that you’d had for a long time, but they (= the publishers) got it straight away? They understand the concept of the book you were aiming to create?

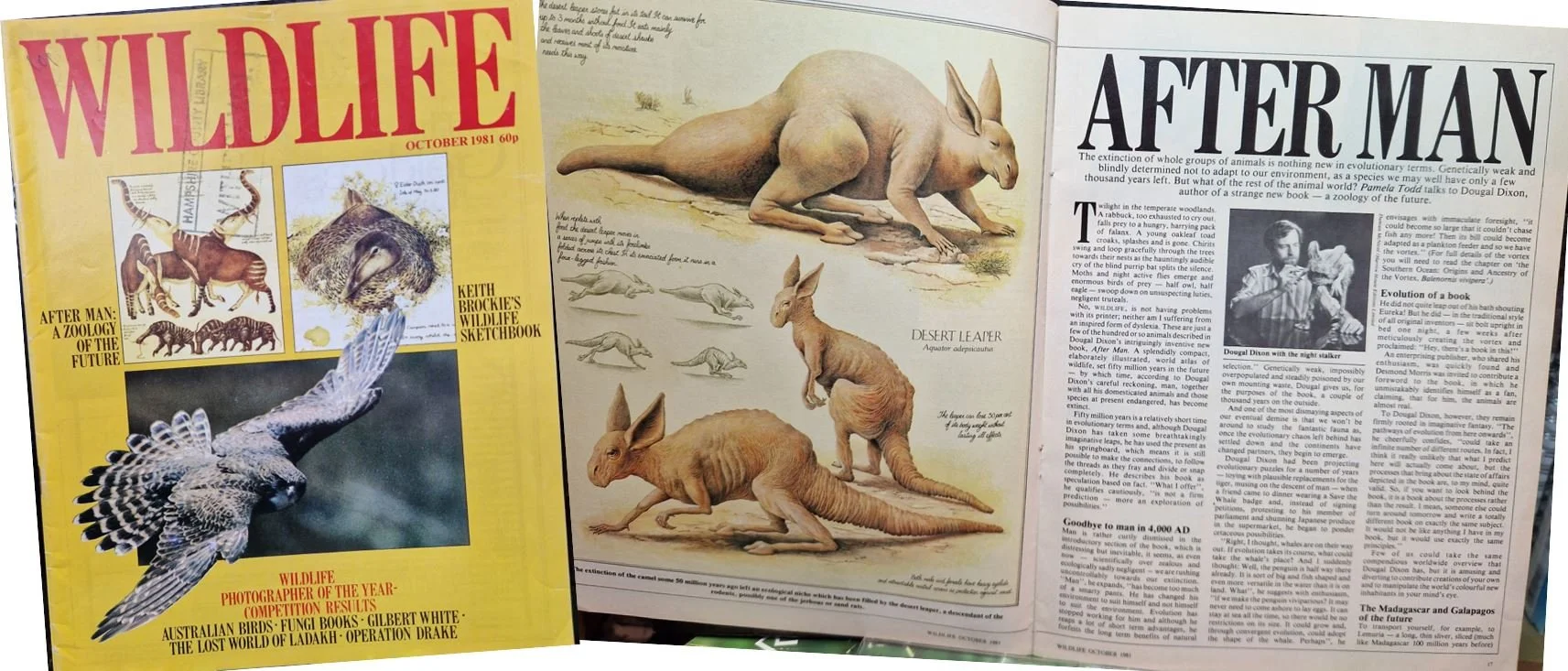

Dougal: Yes, I was very excited about the project, and there were lots of ideas about how it could be tied in to broader efforts concerning publicity. I was told by the publisher that a science-based radio programme on Radio 4 would be interested in covering the story behind the book, and that it would be Barry Cox reviewing it [Prof. C. B. Cox, then of King’s College London]. Well, when the review happened, let’s just say that it was a total demolition job. Cox hated it. And I thought… well, that’s it, I gave it my best shot. However, as other reviews began to roll in, things changed – certainly, the review in New Scientist changed the very low opinion I had of myself. BBC Wildlife and the Smithsonian’s magazine, they also did much to enhance the book’s credibility, and I also had publicity tours both in the UK and the USA.

Caption: After Man is one of so many books that I heard about, and read about, long before I ever saw a copy. The October 1981 issue of Wildlife magazine (the ancestor of BBC Wildlife) included an article devoted to the book, basically a long-form interview between Pamela Todd and Dougal Dixon (Todd 1981), and my secondhand copy of that included my first look at Dixonian future creatures. From Dougal’s point of view, publicity like this would have been golden.

Darren: It must have been very exciting. So far as I know, this was your first ‘big thing’.

Dougal: Yes. It made me think… there’s a future in this. That is, in popular-level books that use fictitious examples of factual processes, there’s definitely room for a few more. And that’s why I came up with the idea for The New Dinosaurs. Again, I wanted to do the same sort of thing but, this time, I was aiming to create a popular-level book on zoogeography, using fictitious examples to show what the dinosaurs might perhaps be like if they hadn’t become extinct.

Darren: That raises a question I have about that book. Were you coming up with the speculative animals first, or were you led by the zoogeography angle?

Dougal: It would have been a bit of both, I think (hard to remember all the details after all this time, of course). On balance, it was the pushing of the zoogeography – a fairly unfamiliar aspect to so many people – that was the main impetus here. I often wonder, however, with these books whether the people that look at them simply see them as picture books of funny animals.

Darren: I think that’s definitely true, to a degree, for some people... but not for the ones that matter! Quite a few people have said that some of the ideas that feature in The New Dinosaurs presaged modern discoveries. You’ve got small, tree-climbing theropods, fuzzy integument on dinosaurs, striding, terrestrial pterosaurs…

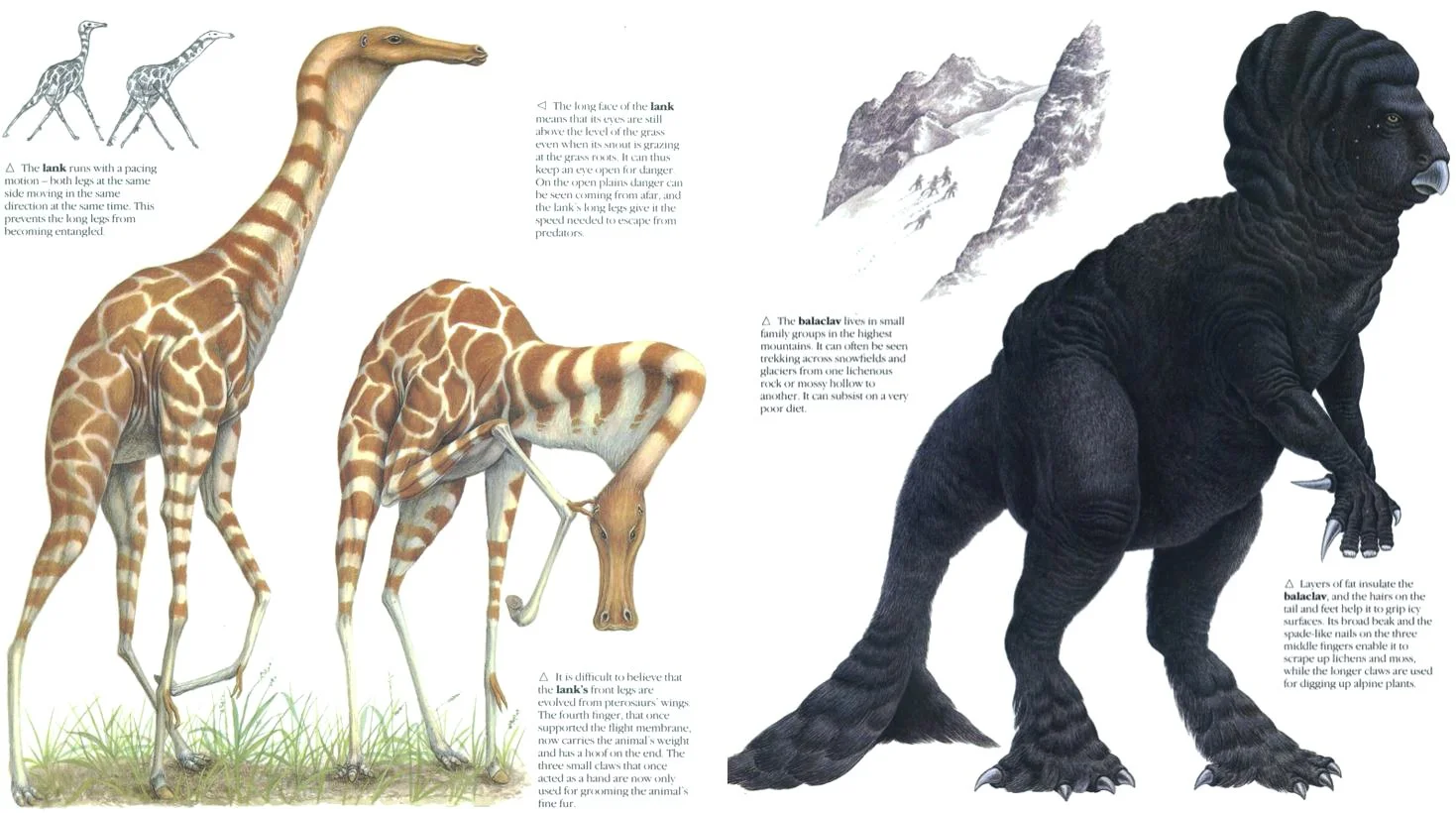

Caption: two of my favourite animals from The New Dinosaurs (Dixon 1988), the Lank (at left) and Balaclav. A couple of decades ago, I never much liked the animals of The New Dinosaurs, my thinking being that they mostly fail as realistic extrapolations of Mesozoic animal evolution. Other people who work on Mesozoic animals have said likewise, most notably Greg Paul. But more recently I’ve slowly come around to the idea that they might be better imagined as animals that deliberately mirror those of our own timeline, just re-imagined as the members of ‘Mesozoic’ groups. In other words: if we have to have a world with pandas, mountain goats, monkeys and rorquals, but have to have those animals represented by ‘Mesozoic’ groups, what might we get? Images: Steve Holden; Philip Hood, both from Dixon (1988).

Dougal: I remember at the time thinking that – to make this work, I’m going to have to embrace the extreme left-wing of vertebrate palaeontology, so that’s when I started reading work by Bakker and people like that, even though I was very much a traditionalist (in terms of dinosaurs) when I needed to be.

Darren: So you were definitely inspired by the controversial ideas of the Dinosaur Revolution during this project?

Dougal: Oh yes, very much.

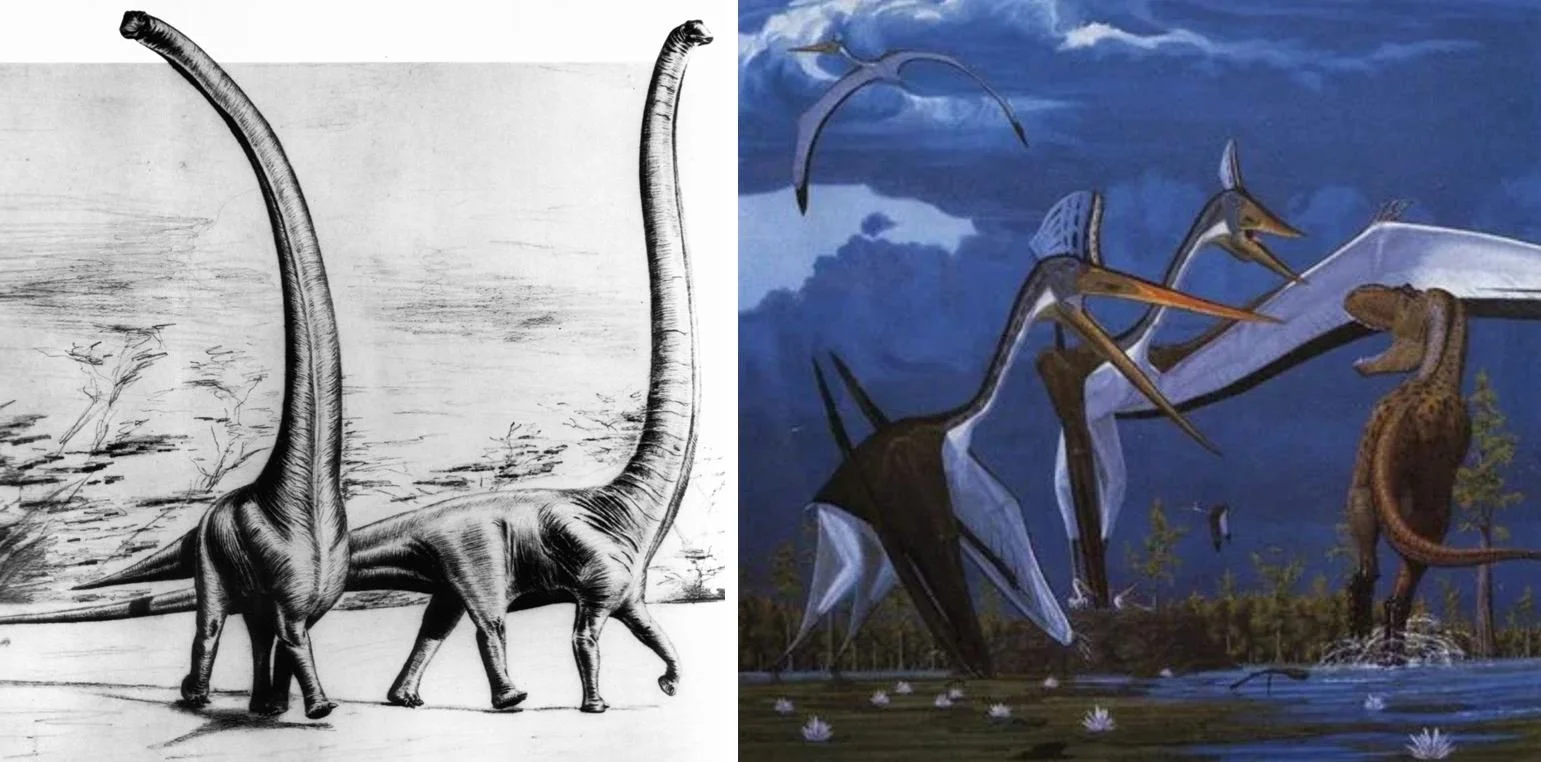

Caption: we’re going through a phase right now of better appreciating the incremental nature of how our ‘modern view’ of Mesozoic archosaurs was compiled (see my comments on the Dinosaur Renaissance in 2021’s Dinopedia). Nevertheless, Robert Bakker’s and Greg Paul’s sleek, dynamic dinosaurs and pterosaurs ushered in a new age of how these animals might be visualised. Illustrations like (at left) Bakker’s fast-moving Barosaurus pair from the 1960s and (at right) Paul’s svelte, narrow azhdarchid pterosaurs and tyrannosaurs influenced the animals of Dougal's The New Dinosaurs. Images: (c) Robert T. Bakker; (c) Gregory Paul.

Darren: There have been a couple of recent articles that have drawn attention to this. There’s an online article by Riley Black highlighting the fact that things considered pretty radical in The New Dinosaurs now appear on the ball, or at least pretty reasonable, in view of recent discoveries [that article is here].

Dougal: Well, I’ve got pterosaurs running around like giraffes!

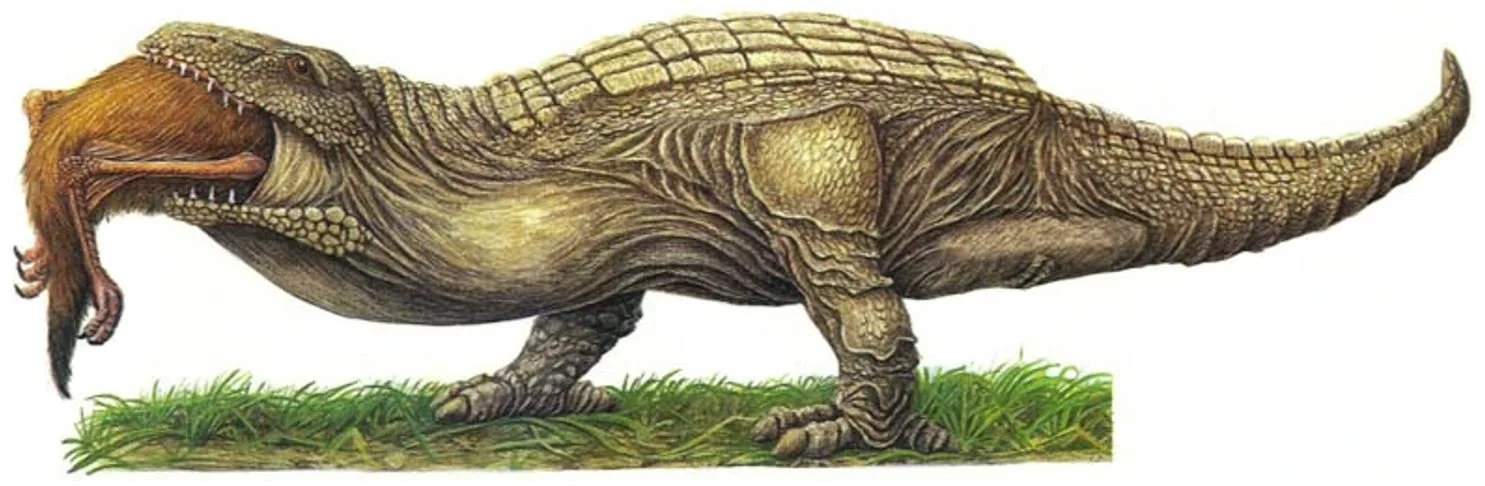

Darren: Exactly, yes. So the animals of The New Dinosaurs weren’t coincidental inventions: they were extrapolations based on what Bakker and Paul had said. Having said that, there are creatures in The New Dinosaurs that don’t look modern in terms of their anatomy and/or behaviour. There’s a specialised scavenging tyrannosaur – the Gourmand – for example. That’s not a Bakkerian dinosaur, it’s a Beverly Halstead dinosaur: it’s a giant, sluggish, carrion-eating tyrannosaur.

Caption: the Gourmand Ganeosaurus tardus, a giant, scavenging tyrannosaur from The New Dinosaurs. Image: Steve Holden, from Dixon (1988).

Dougal: Remember that the whole of The New Dinosaurs was very much a cognitive exercise in the same vein as After Man. I was interested in patterns, and pushing the patterns to an extreme. So, in the lineage leading up to the Gourmand, the idea is that we’re seeing a pattern in which the forelimbs become smaller and smaller and smaller, eventually disappearing.

Darren: If you were to do The New Dinosaurs today, would you do it any different?

Dougal: Yes I would. If you’re asking for specific examples – it’s difficult to know where to start...

Darren: Absolutely. Obviously we have so many feathery theropods now they’ve even been described as mundane, plus now there are even filamentous structures on ornithischians. One of the things I like about the book is that it doesn’t just depict a ‘dinosaurs only’ world. There are mammals in there, there are big pterosaurs, some plesiosaurs. One of the things I think we’ve learnt about the Mesozoic that makes it more interesting is that it’s not just a ‘dinosaurs only theme park’: you’ve got these other groups, and since the book was published, since the 1990s, we’ve learnt that, for example, in Late Cretaceous South America we’ve got an enormous radiation of terrestrial or semi-terrestrial crocodyliforms living alongside theropods. Obviously crocs went on to have their own, rich Cenozoic history, but if you have more complex animal communities at the end of the Cretaceous, and then don’t have the end-Cretaceous event, you end up with a completely different Cenozoic and modern day biota, perhaps with these groups doing things that we don’t see in our timeline.

Caption: ugh, yet more Dougal Dixon fan-art made by myself. This fanciful montage shows various smaller and ‘mid-sized’ creatures from The New Dinosaurs, including Lank, Springe, Northclaw, Treepounce, Nauger, Cutlasstooth, Cribbum, Pangaloon and (in the water) Watergulp, Pouch, Plunger and Glub. The animals are not scaled at all correctly. Colouring by Ethan Kocak. Image: Darren Naish and Ethan Kocak.

Dougal: Indeed. Imagine then, that, with the formation of the South American landbridge, we’d see migration and diversification involving these animals as they moved north.

Darren: Greg Paul did a review of The New Dinosaurs. It’s kind of critical, but it does basically say at the end “Well done, it takes guts to do something like this and I respect that”. It gives him an excuse to invent his own ‘modern’ non-bird dinosaurs, including weird new horned dinosaurs, cursorial tyrannosaurids...

Dougal: Yes, I’ve seen that illustration.

Caption: Dougal has made several large-scale models of theropods and other animals. This photo, taken in August 2013, shows Dougal talking with palaeoartist Bob Nicholls; Dougal’s feathered oviraptorid model is at left. Image: Darren Naish.

Darren: Going back to the subject of pitching these books to publishers in the first place, this would mean that it was your artwork, your illustrations, that led to these projects being a success. What I’m getting at here is that... thinking of, say, the future animals of After Man, we know that you invented these creatures as extrapolations based on extant animals. And I’ve seen your illustrations, the models you’ve made; I know you’re a very talented artist. So why, in these books, don’t we see your artwork, your illustrations? Instead, we see depictions of these animals re-imagined by other artists (usually wildlife artists): people like Denys Ovenden, Philip Hood. Is the decision to use art by these people made by the publishers?

Dougal: It is a publisher decision, yes. At the beginning of the production of After Man, I did produce detailed illustrations for the artists to follow... and the artists would ignore them, and draw any old science fiction-based creature. So I really did have to bring them to heel. I ended up producing draft line illustrations that were so detailed, they just needed to ink them in to produce the final products. It’s a shame. In reality, my stuff should have been in there, yes.

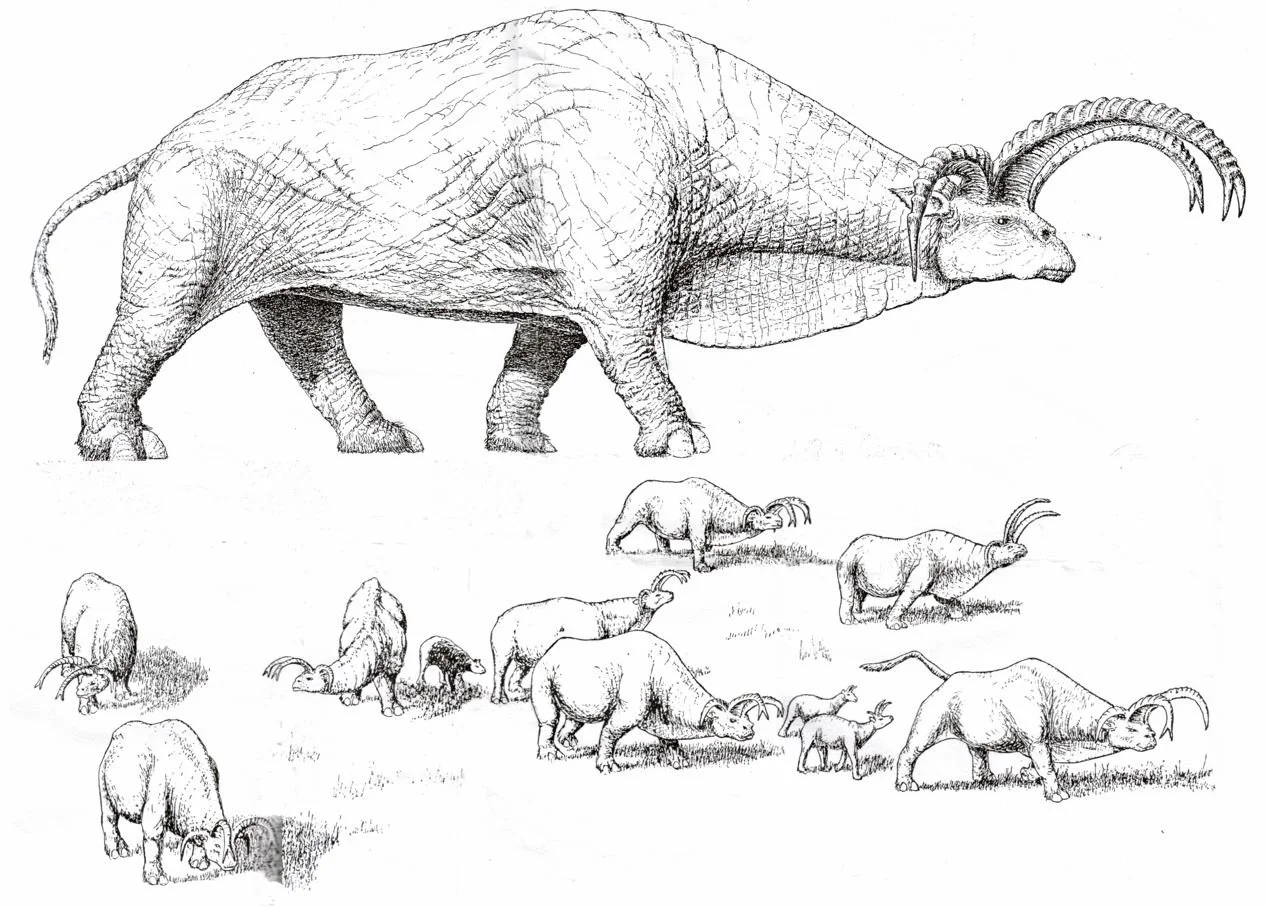

Caption: a set of original Dougal Dixon illustrations, showing a foraging gigantelope herd, and detailed profile drawing. Numerous such sketches exist and were unpublished and mostly unseen when I first published this interview text in 2014. They and many others are now at Dougal Dixon’s website. Image: (c) Dougal Dixon, used with permission.

Darren: Where are all those illustrations of yours now? Do you still have them? Keeping in mind that the world of publishing is very different now thanks to self-publishing, ebooks and online pdfs and so on, I just wonder whether you’ve ever thought of getting them published?

Dougal: I do still have them. As for getting them published... I hadn’t thought of that, actually. [UPDATE: see Dixon (2021), since some large amount of this original art has now been published.]

Dougal: So, we’ve spoken now about After Man, which is about future evolution, and The New Dinosaurs, which is about zoogeography. Then there’s Man After Man – a project I was never keen to be involved in, the title of which was originally being kept for a project of my own. And that project again involved fictitious examples of factual processes. I thought: right, let’s have the current world collapsing through overpopulation, famine and so on, and the idea that mankind needs to escape destruction. What does mankind do? Invents time travel and moves 50 million years into the future and sets up civilization then. Then what we’ll have is that all the man-made catastrophes, all the ecological disasters... they happen all over again. So I’ve got this world already created in After Man, and I’m now going to destroy it... this was going to be Man After Man. But the name Man After Man was taken for that other disaster of a project.

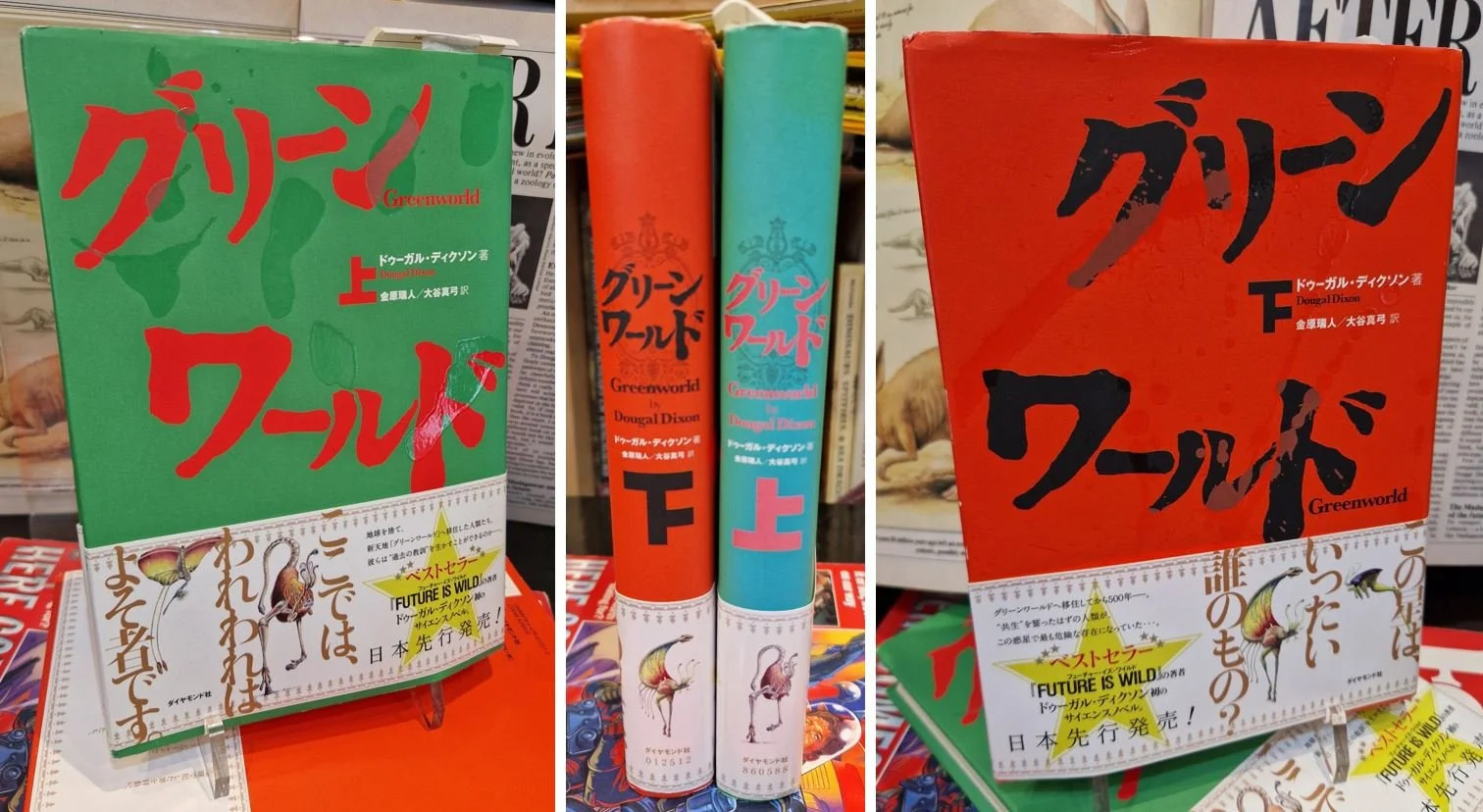

Caption: proof that the Greenworld volumes exist, and that I own them (thanks to Dougal). As Japanese books, they operate ‘backwards’ relative to what English speakers are used to. Both volumes are substantial, containing way over 300 pages each. It would be great if they existed in English! Images: Darren Naish.

Darren: So, Man After Man would originally have been near-future humanity’s impact on the far-future creatures of After Man?

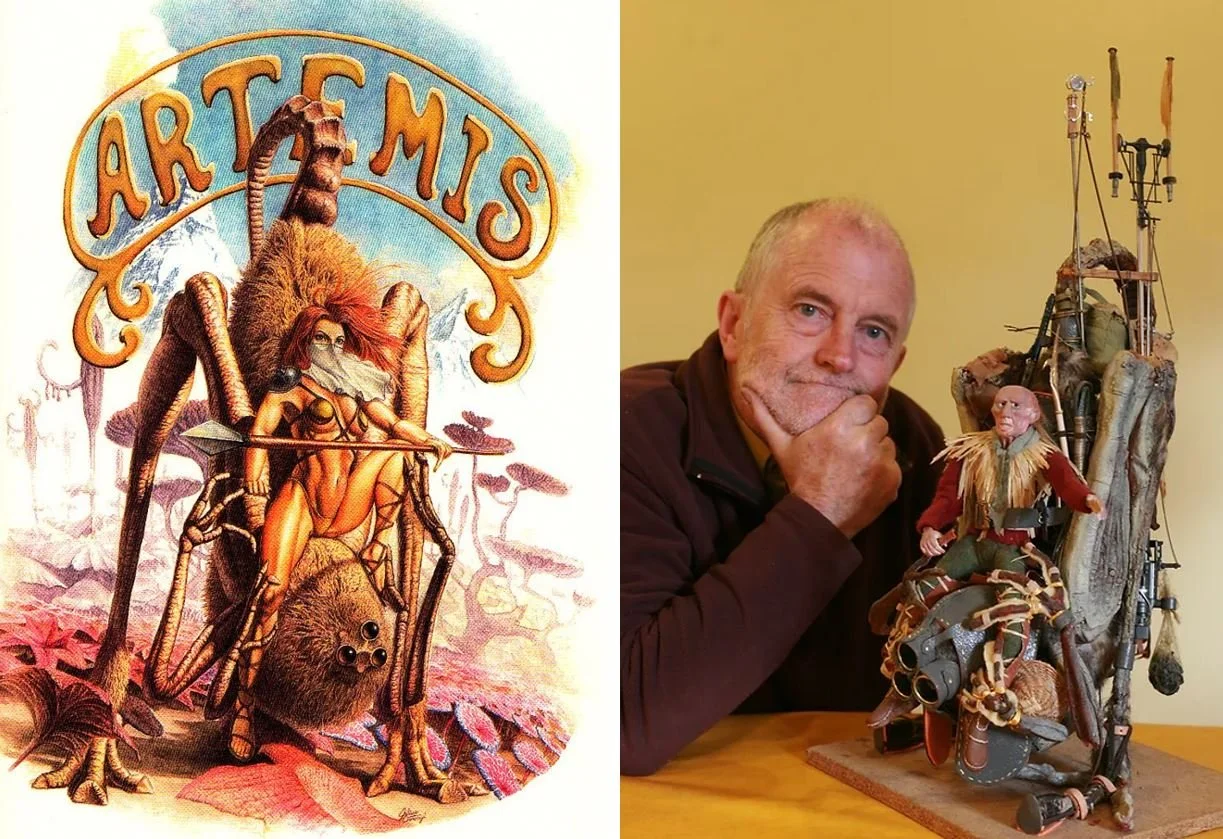

Dougal: Yes. What I did with that concept, quite a few years previously, is create an alien biota for an Earth-type planet in a far solar system, but based on the same biochemical processes that created life today. It was actually done as a design exercise to show to the local science fiction group. I had the whole ecosystem worked out. I thought: I’m going to use the Man After Man scenario on that. I’m going to have colony ships going to this planet. This became a book, called Greenworld.

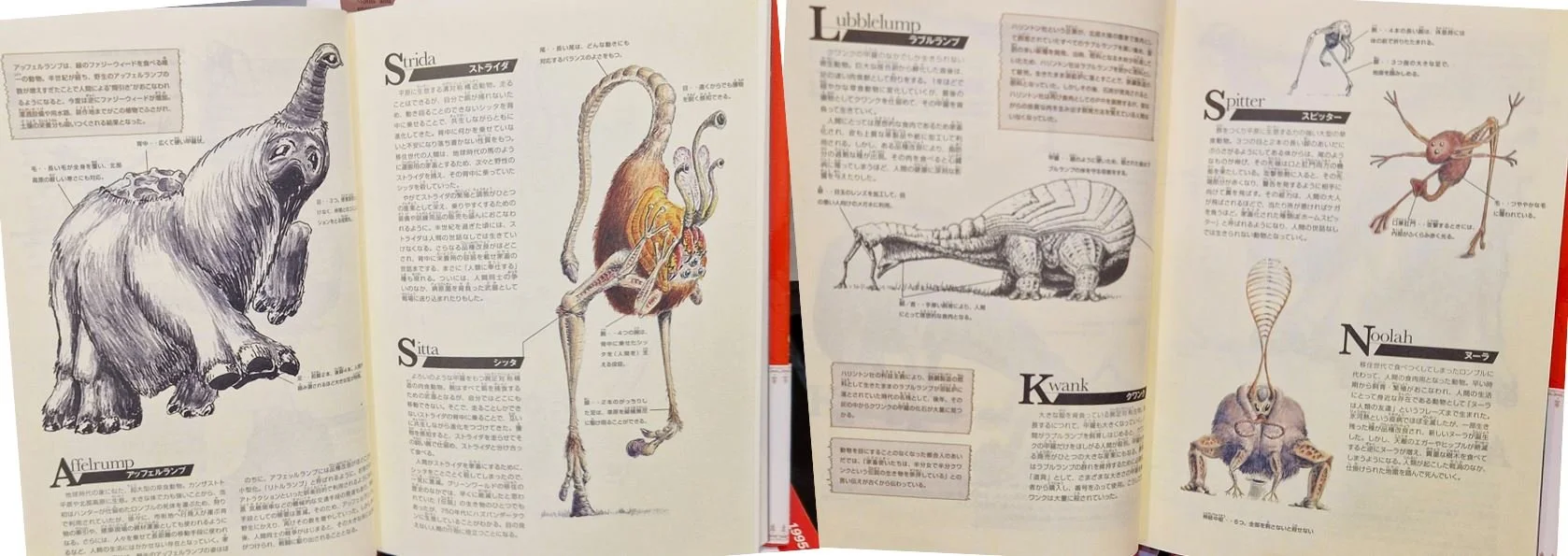

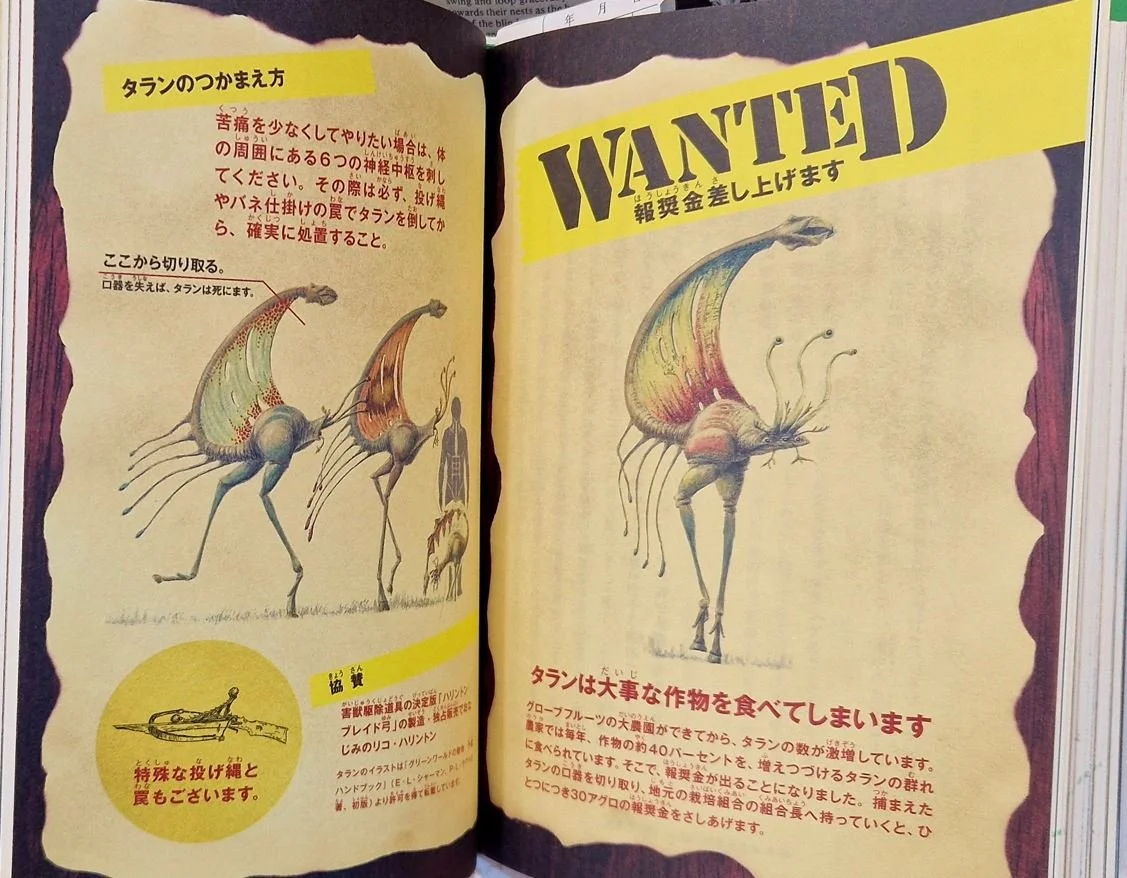

The concept is that human colonists arrive in a pristine natural environment and immediately set about screwing it all up. The way it’s arranged is as a series of short stories that follow different generations of the same few families, thereby building up into a sort of dynastic epic, covering a thousand years of colonisation on this planet. The planet ends up as a smoking ruin, echoing the planet that was left behind at the start of the story. All of the illustrations are done by me, for a change (except for a couple of things that involved techniques that I’m unfamiliar with). The illustrations reflect the idea that the reader is basically eavesdropping on the lives of the characters of the book. We get to see excerpts from field guides, from herbals, and recipes, warning signs, bounty notices, advertisements, and all sorts of stuff like this – the idea being that, if you look at this combination of images, you build up an idea of what the biota is like.

Caption: pages from within both of the two Greenworld volumes, showing just a few of the many alien species encountered on the planet. Body plans very different from the ones we’re more familiar with are the norm, but the starting point was a pentameral pattern like that of echinoderms. There are no native humanoids, blue-skinned or otherwise. Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Caption: the human colonists of Greenworld cause extinctions that occur in a staged, sequential pattern (among the earliest to go are large ‘pest’ species, like the Tallun shown here) and are described on a generational, long-term basis. What unfolds on the planet is of course a mirror of events that have occurred, and are still occurring, here on our homeworld. Images: (c) Dougal Dixon.

Darren: This is great. And has this material been collated? I mean, are there plans to get it published?

Dougal: It has been published, as a book, but only in Japan. My stuff is extremely popular in Japan. In fact my name has a hell of a lot more clout in America and Japan than it does here in the UK.

Darren: I do recall seeing some of the images from Greenworld on TV. I remember in particular the Strida creatures.

Dougal: That’s right – this was before I put it together, so parts of the project appeared here and there. There was the BBC programme Natural History of an Alien...

Caption: a The Future is Wild banner, from the (still active!) website, showing several star creatures of the series, including Carakiller, Gannetwhale, Megasquid and Toraton. Image: (c) The Future is Wild.

Darren: Yes. This featured the tripodal leaping creature and the giant conch-like animal. Let’s talk about The Future is Wild. The book is co-authored with Joanna Adams, is that right?

Dougal: Yes, Adams is a producer of television documentaries with a very good track record, who had always wanted to do a project based around the concept of evolution projected into the future. So, when this started crystallising about 15 years ago, she brought together a few consultants who might have ideas along these lines, like R. McNeill Alexander and Jack Cohen. And Jack said “Have you read After Man, by Dougal Dixon?”. So that’s where my name was mentioned, and hence I became part of the project. I was brought in as a consultant but, what with all these other consultants, my role evolved to become that of a designer, inventing the animals that had been suggested by this suite of consultants. I ended up designing all the animals to their briefs and passing along the designs to the animation studio. Since I’m an established writer, I also got to write the tie-in book. So I didn’t start any of this and was a mere hired hand in it.

Caption:The Future is Wild features a far-future scenario that’s been entertained several times in speculative fiction…. Squid World! Here are two terasquids from the Northern Forest of 200 million years hence, the arboreal and intelligent Squibbon (at left) and the giant, graviportal Megasquid. Image: (c) The Future is Wild.

Darren: Ah. My imagining was always that they’d seen After Man, thought “this would make a great TV series”, but then found that – due to copyright or some other reason – they were unable to use the original creatures and hence had to invent new ones, similar but slightly different.

Dougal: Well, there is a constraint of that sort. By that time, DreamWorks SKG had bought the rights to After Man and optioned it, so we could do nothing with the original animals meaning, indeed, that a whole new suite of beasts had to be invented.

Darren: So we have giant flightless gannets instead of giant penguins.

Dougal: Exactly. They came up with giant penguins, but then the lawyers were --- no no, you can’t!

Caption: I think we can question the idea that gannets – which are plunge-divers, and wing-propelled when underwater – would give rise to long-jawed animals of such seal-like form, but giant, flightless, marine seabirds were needed for The Future Is Wild, so gannetwhales it was. Image: (c) The Future is Wild.

Darren: Did anything ever come of the DreamWorks project?

Dougal: No. DreamWorks finally abandoned it and it was then picked up by Paramount. It’s still getting optioned; in fact the option’s up for renewal this month, I need to find out what’s going on there. [UPDATE: according to Dixon (2021, p. 136), “No film ever resulted from this option so the scenario is now available again”.]

Darren: In the Earth of The Future is Wild, Amazonia is now a grassland, what’s currently Bangladesh is now flooded, forming the great Bengal Swamp...

Dougal: Yes, and this is completely a different tack from what I did in After Man. The geography had changed in After Man because of plate tectonics, but the various vegetation zones and biomes – I thought I’d keep them as close as possible to those of today, since the reader – being faced with all these new and terrible animals – will at least recognise the background.

Darren: There are four-winged birds in The Future is Wild called windrunners, specialised for flight over the Himalayan Plateau.

Dougal: They were created by Phil Currie, the consultant providing ornithological expertise on the project. I was amazed: a palaeontologist coming up with speculative evolution, with something as radical as four-winged birds. I thought: let’s go for it, this is going to be spectacular.

Darren: I always wondered if it was a coincidence that the windrunner was invented at about the same time as Microraptor was announced.

Caption: at left, the four-winged Great blue windrunner of The Future is Wild, a crane built for a lifestyle that involves migration across a vast, elevated plateau (formed when Australasia collided with Asia). At right, a The Future is Wild promo image, showing a flish of the far future. Flish are air-breathing actinopterygians (ray-finned fishes) capable of true flight and among the last surviving actinopterygians, most of which died out in an extinction event 100 million years hence. Images: (c) The Future is Wild.

Dougal: No, it [= the invention of the windrunner] was before that... unless Phil knew about Microraptor before that.

Darren: my thinking was that windrunners were so weird, so revelatory – why would anyone create a four-winged bird? – that a coincidence here would be remarkable, but I’ve since remembered that there was this early 20th century concept of the Tetrapteryx. In other words, there were ideas about four-winged fliers long prior to the discovery of Microraptor.

Dougal: I should finish here by saying that Jo Adams and team were all fired up to work on a big screen version of The Future is Wild with Warner Bros (I think) and had raised the funding for the television series The Future is Wild 2. However, on the big screen side, Avatar had raised the bar so high that Warner Bros (I think) pulled out. And on the small screen side, Discovery Channel announced that they were going to stop doing documentaries; instead, they were going over to dancing chefs and celebrity idiots and so the funding for that collapsed. Not a good year!

Darren: Any future ideas? What’s next? You’ve spoken about Greenworld.

Dougal: Yes, an English language edition of that needs to appear. [UPDATE: see Dougal’s website section here.]

Caption: we experience the flora and fauna of Greenworld through the literature, images and advertisements created by the people who live there. This poster – advertising an Artemis product – features a Strida... and I think a human as well. But it turns out that this image is not exactly representative of how things unfold on the planet, and a real Strida rider ends up more like the model shown at right (model by Dougal Dixon). Images: at left, Julius Csotonyi, from Dixon (2010); at right, (c) Dougal Dixon.

Darren: After Man has been repackaged a few times – there are several different designs with different covers. I saw one recently with a Night stalker on the cover. Oh – any thoughts on the 2013 movie After Earth? [UPDATE: After Earth is irrelevant and forgotten today but was new enough when I did the interview in 2014. Its inclusion of future animals, including a novel big cat, a giant, condor-like raptor and North American baboons, led to suggestions that it was inspired by After Man.]

Dougal: I haven’t even seen it, but I’m told by people who have seen it that it has no connection whatsoever with After Man. In any case, it more or less sank without a trace.

And that’s where we end things. I hope you enjoyed this updated version of a transcribed 2014 interview, and I hope that it provided interesting – and new – background to Dougal’s several projects, all of which have been a major inspiration to so many of us. This interview wouldn’t have happened without Dougal’s co-operation, and I sincerely thank him for his patience, kindness, time and assistance. Thanks also to the team at Breakdown Press for providing books.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on Dixoniana and other aspects of speculative zoology, see…

Oh no, not another giant predatory flightless bat from the future, March 2007

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Giant flightless bats from the future, November 2012

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

The LonCon3 Speculative Biology event, August 2014

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, July 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

Dougal Dixon’s After Man, the Initial Pitch Document, June 2020

Refs - -

Anon. 1995. Life on earth – 50 million AD. Focus January 1995, 56-60.

Dixon, D. 1981. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Granada, London.

Dixon, D. 1988. The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution. Salem House, Topsfield (MA).

Dixon, D. 1990. Man After Man: An Anthropology of the Future. Blandford, London.

Dixon, D. 2010. Greenworld (two volumes). Diamond, Tokyo.

Dixon, D. 2018. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Breakdown Press, London.

Dixon, D. 2021. After Man: A Zoology of the Future (40th Anniversary edition). Breakdown Press, London.

Dixon, D. & Adams, J. 2004. The Future Is Wild: A Natural History of the Future. Dorling Kindersley, London.

Naish, D. 2014. Speculative zoology. Fortean Times 316, 52-53.

Thomann, V. 2024. A “speculation built on fact”: on Dougal Dixon’s zoology of the future. In Castle, N. & Champion, G. (eds) Animals and Science Fiction. Springer Nature, pp. 345-362.

Todd, P. 1981. After man. Wildlife 23 (10), 16-18.