It’s World Turtle Day, and what kind of person doesn’t love and admire turtles?!

Caption: I sometimes consider it kinda odd that a group of reptiles built the way they are have been so strongly associated with amphibious and aquatic habits across their history, but here we are. At left, an unusual close-up view of a captive Green turtle Chelonia mydas. At right, a Pseudemys turtle (maybe a Florida red-bellied P. nelsoni?) observed in the wild in Florida, in a swimming pool of all places. Images: Dave Hone, used with permission; Darren Naish.

Caption: aquatic turtles at very different ends of the size spectrum. At left, a pleurodire, specifically a Roti Island snake-necked turtle Chelodina mccordi observed at Brighton Aquarium (sorry the snout is cut off: these animals move far too much to enable nice, clear photos). At right, a reconstruction of the gigantic Late Cretaceous North African sea turtle Ocepechelon. Images: Darren Naish; Joschua Knüppe.

Because I’m drowning in work, I have nothing ready to go, so here are random turtle-themed thoughts relating either to material published in the past here at Tet Zoo, or connected to content that’s been amassed for my in-prep textbook… which, yes, is still a thing and due to be finished one day. Oh, this isn’t the first time that World Turtle Day has snuck up on me by surprise – ha, the irony – since I see from Tet Zoo articles of the dim and distant past that exactly the same thing has happened before, as evidenced by…

Turtles I Have Recently Seen, June 2015

Pleurodires or side-necked turtles occur today in South America, Africa, Madagascar and Australasia and are less diverse and less widespread than their sister-group, the cryptodires. There’s sometimes the implication that pleurodires are ‘more archaic’ than cryptodires (possibly due to Northern Hemisphere chauvinism) but there’s no reason to adopt this given that both lineages are of equal age: it’s true that pleurodires are less diverse than cryptodires (in ecology, morphology, size and habitat choice) but this is less of an issue when extinct taxa are accounted for.

Caption: the matamata(s) is taken for granted as an odd pleurodire turtle, but it’s something very, very special. Just peer into the eyes of this surreal, highly aquatic, flanged, cryptic predator with a proboscis and remind yourself that it’s a turtle. The suggested use of plural there is a reference to the fact that there might be more than one matamata species. The photos of the captive individual appear here courtesy of Mark Hollowell; the drawing is by me. Images: Mark Hollowell (used with permission); Darren Naish.

The fossil record reveals that pleurodires were once far more widespread, exhibited more anatomical disparity, and occurred in a greater variety of habitats than they do today, especially during the Cretaceous and Paleogene. I haven’t written about pleurodire diversity in much detail, to my shame, but I did publish a whole series of articles on matamatas at Tet Zoo ver 2 back in 2010…

Matamata: turtle-y awesome to the extreme, June 2010

The familiar Matamata, known to us all since the 1700s, and its long, fat neck (matamatas part II), July 2010

“Adaptation perfected” (possibly) in a turtle’s head (matamatas part III), July 2010

Turtles that suck, turtles that blow (matamatas part IV), August 2010

Giant fossil matamata turtles (matamatas part V), April 2011

Caption: another matamata montage, showing a familiar photo of a captive one ‘snorkeling’, and captive individuals observed in various UK collections. Images: Francis Miller, from the Time-Life International 1963 volume The Reptiles; Darren Naish.

Softshell turtles or softshells (Trionychidae) are one of my favourite turtle groups and are a widely distributed lot of aquatic cryptodires. They possess a flexible proboscis (a feature we might not predict based on their osteology alone) and a soft dermal covering to the carapace that extends well beyond the shell’s bony margins. Key features include the presence of a wrinkled shell bone texture and the loss of virtually all carapacial scales and scutes.

Caption: at left, a surprisingly big African softshell Trionyx triunguis photographed at the mouth of the Congo River; this is one of a series of photos shared in 2009 at the SA Reptiles discussion board. At right, skull of an Indian narrow-headed softshell Chitra indica, another large member of the group. Note how elongate and (yes) narrow that skull is, and how the orbits are aaaaaalll the way at the front. Images: © Herphabitat (originals here); Darren Naish.

Softshells are typically associated with tropical and subtropical swamps, lakes and pools in North America, Africa and Asia but also occur in estuarine and marine environments. I’ve found them especially exciting over the years due to their ecological flexibility, the relatively large sizes reached by individuals within some species, and their sometimes ferocious predatory prowess. Plus they often look very, very weird.

In combination, these factors help explain why they’re one of the few turtle groups that I’ve covered here at Tet Zoo on repeat occasion, though I haven’t given them due credit because boy do they need more coverage. Check out…

The goat-eating hot water bottle turtles, November 2007

Giant African softshells – wow!, January 2010

In case you forget, softshell turtles are insanely weird, December 2011

Caption: a Florida softshell Apalone ferox that I photographed in captivity in 2011. The red hue is partly caused by the colour of its basking lamp. Either way, the turtle still looks very, very strange. Image: Darren Naish.

Leatherbacks or leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelyidae) are named for the extant Dermochelys coriacea, a remarkable marine turtle well known for its substantially reduced carapace encased in leathery skin, enormous front flippers, deep head, prominent pseudoteeth, and size (the carapace can be 1.8 m long and the flipper span can be 2.7 m).

Dermochelys is a predator of cnidarians (jellies, siphonophores) that dives as deep as 1.5 km. It used to be considered a specialist predator of these animals but there are some indications that it might be better characterized as a generalist, since we now know that it also eats algae. It’s fast growing (reaching maturity in less than a decade) and near-globally distributed. There’s tons to say about it. I have covered the fossil history of leatherbacks in my 2023 book Ancient Sea Reptiles but still need to write about the behaviour, anatomy and ecology of the extant species.

Ancient Sea Reptiles Is Out Now, February 2023

Caption: at left, this blog’s author with a life-sized model of the Harlech leatherback at Anglesey Sea Zoo. At right, one of the original photos of the actual animal, which stranded on the Welsh coast (after drowning in fishing gear) in 1989. It was huge, weighing 916kg. Images: Toni Naish; © Western Mail & Echo, Wales.

Snapping turtles (Chelydridae) are excusively American today and are represented by two genera: the common snappers (Chelydra) and alligator snappers (Macrochelys; it is termed Macroclemys in some of the older literature). These are strongly aquatic, omnivorous turtles with large heads, renowned for their powerful, hooked beaks and extremely rapid strikes. Molecular studies indicate that chelydrids are close relatives of mud and musk turtles. I love snapping turtles and have had reason to write about them a few times at Tet Zoo…

They bite, they grow to huge sizes, they locate human corpses: the snapping turtles, part I, February 2006

Snapping turtles, part II: hyperexcitability, supercooling, and the inevitable recolonisation of Europe in the Anthropocene, February 2006

Snapping turtles, part III: bite, lunge, lure and snap, May 2006

Caption: an unusually pale Common snapping turtle on show at Bluereef Aquarium, Portsmouth, UK. Images: Darren Naish.

Tortoises (Testudinidae) are the most terrestrial of testudines, their terrestrial features including a strongly domed carapace, large (even gigantic) size, compact hands and feet and hoof-like or nail-like unguals. An external dermal covering of large, sometimes plate-like or spiny, scales often covers the limbs and the snout is typically deep, broad and short. This is another group that I’ve covered here quite a few times. Check out…

Gilbert White’s pet tortoise, and what is ‘grey literature’ anyway?, October 2008

Turtles that eat bone, rocks and soil, and turtles that mine, April 2014

Tortoises as Consumers of Carrion, March 2021

Tortoises as Consumers of Carrion, Part 2, June 2021

Leopard Tortoises, January 2022

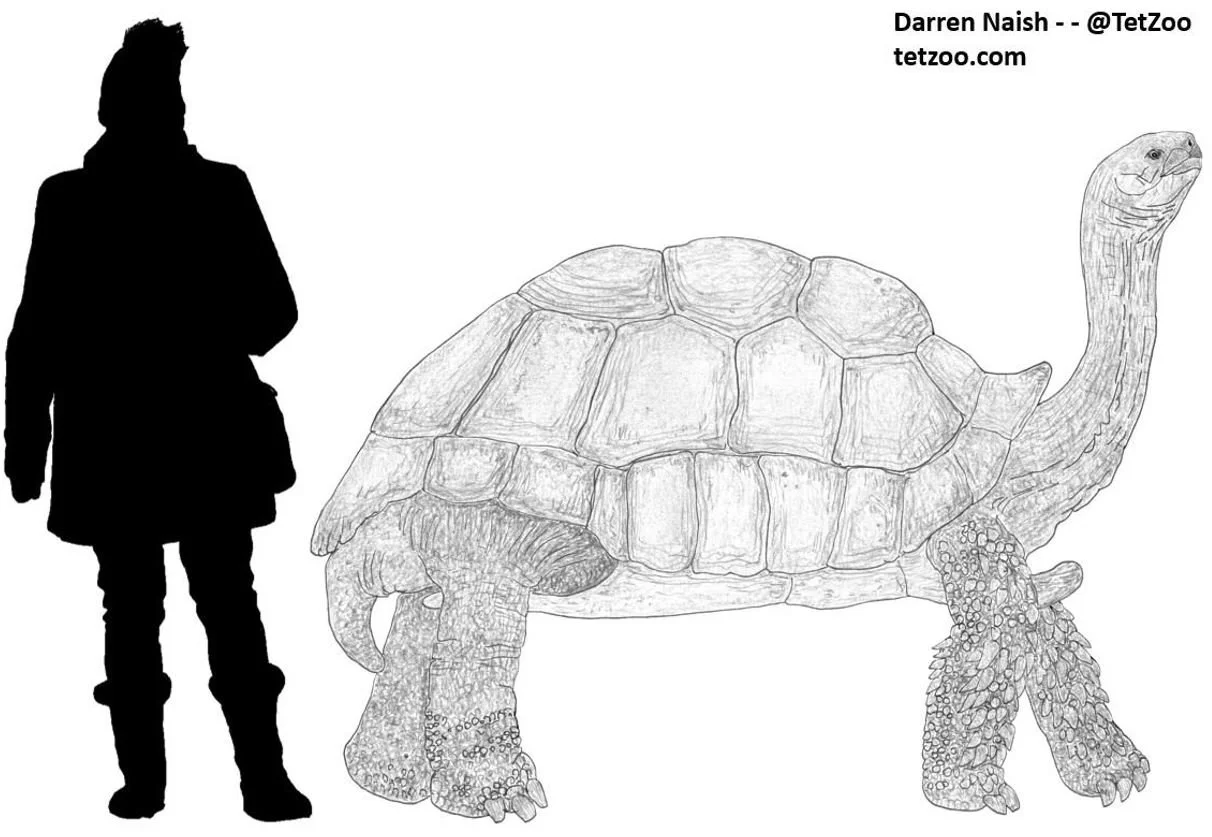

Megalochelys, Truly a Giant Tortoise, January 2024

Caption: Megalochelys, a giant tortoise of prehistoric Eurasia, included giant specimens where the CCL (curved carapace length) was 2 m long. Here, I’ve followed the long tradition of showing this animal to scale with a modern human: the one used here has a standing height (without hat) of 1.6 m. Image: Darren Naish.

That will have to do for now. How I’ve love to write about turtles at length. But I have to stop there. Thanks to LOLAMARINA – if that is her real name – for reminding me that it’s World Turtle Day once again, and let us all remember that so many turtle species worldwide require conservation and compassion if they are to persist. That means helping to maintain the existence of wetlands, woodlands, natural deserts and coasts, preventing pollution, and objecting to their exploitation in the pet and restaurant trade. We love turtles; the world will be so much poorer without them.