There was once a time when horned dinosaurs were given a very, very odd look….

Regular readers will know that a vast amount of content – produced for this blog over the space of more than ten years – is out there, but now mostly ruined, corrupted and hard to find. I tend not to like recycling this older material for the blog (mostly because there’s so much new content I want to publish)… but, when times are tough (as they are right now), I’m figuring that recycling is better than nothing. And thus we find today’s article: a recycled piece from the archives. It originally appeared at TetZoo ver 2 (the ScienceBlogs years) in April 2009 (the original is here), and here it is again…

Caption: no, I do not take seriously the suggestion that the ceratopsian frill (and its associated bony and keratinous structures) evolved within the context of it being an anti-predator structure, as depicted here. Abundant evidence shows instead that it was an extravagant signalling structure that predominantly functioned in sociosexual behaviour. These models are on show at the National Showcaves Centre for Wales, Brecon Beacons National Park, Wales. Image: Darren Naish.

One of the most distinctive features of ceratopsian dinosaurs is the conspicuous bony frill, formed from the parietal and squamosal bones, that projected backwards (and sometimes upwards too) from the rear margin of the skull.

Caption: ceratopsian frills are among the most extravagant structures of any dinosaur group. They can contain massive bony ‘windows’ (as in the Chasmosaurus belli skull ROM 843 shown at left), or be solid (as in the Triceratops shown at right, photographed at Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart). Images: Darren Naish.

The ceratopsian frill was thus a fundamental part of the skull, this meaning that it was moved (up or down, or to the side) whenever the animal moved its head. The fact that the ceratopsian occipital condyle is damn-near spherical shows that the head-neck joint was particularly mobile, and that these dinosaurs were well able to dip the snout right down to the ground, to throw the head from side to side, and to point the snout upwards until the frill rested on the shoulders. The frills are typically decorated around their edges by semi-circular bones called epoccipitals, and sometimes possess horns, spikes or mid-line keels.

Caption: ceratopsian jaw musculature as reconstructed in Chasmosaurus and Styracosaurus by Dodson (1996).

Because the supratemporal fenestrae (the openings at the back of the skull that, at their edges, anchor various jaw muscles*) open on the surface of the frill, at least some of the jaw musculature must have extended on to the frill. In normal tetrapods, these muscles are restricted to the areas just around the fenestrae… but ceratopsians aren’t normal tetrapods: the bones at the rear of the skull are horrendously modified. Could, therefore, the massive frill be a specialisation allowing hypertrophied jaw musculature? A number of authors have proposed exactly this, and have imagined ceratopsian jaw musculature extending right across the frill, all the way to the rear margin. As Dodson (1996) explained in his excellent and very accessible book The Horned Dinosaurs, the logic behind this super-muscled frill was flawed: animals do not need gigantic, super-long jaw-closing muscles to have a powerful bite, and the surface texture of the frill is not consistent with a covering of musculature. It seems that the musculature was, most likely, restricted to the areas just around the supratemporal fenestrae.

* Note that the ‘windows’ on the frills of most ceratopsians are not the same thing as the supratemporal fenestrae.

Caption: John McLoughlin proposed that ceratopsian jaw musculature covered the entire frill, and extended over the back. These would - just about - be the biggest muscles ever! Image: McLoughlin (1979).

However, back when the hypothesis of extensive frill musculature was considered reasonable, a truly extreme version was proposed by John McLoughlin in his 1979 book Archosauria: A New Look at the Old Dinosaur. I could actually say an awful lot about this book, since it was one of the first volumes to take the implications of the Dinosaur Renaissance and really run with it. This isn’t the place for that, but McLoughlin did deliberately produce avant garde, perhaps risky, artistic reconstructions. Feathery and furry theropods, slender-framed sauropods and sprightly, prancing ornithopods are all in there…. as are remarkably odd ceratopsians.

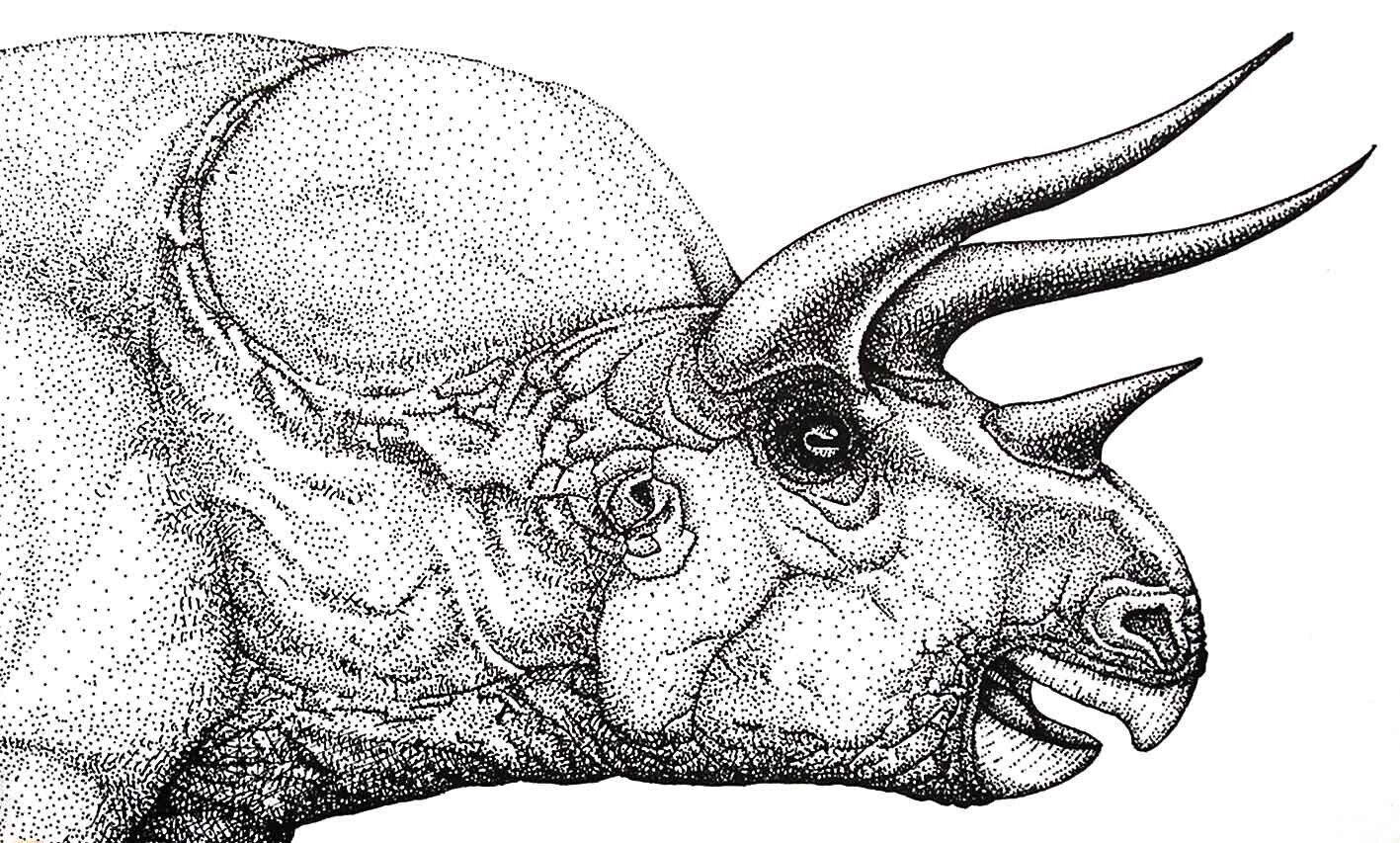

Caption: John McLoughlin’s Triceratops reconstruction from 1979 book. Image: McLoughlin (1979).

McLoughlin (1979) proposed that the ceratopsian frill didn’t just anchor musculature: it was essentially buried by a massive amount of muscle that extended around the back of the skull, and across the shoulders too. I never saw John’s book until I was in my 20s, and only knew of his ‘alternative’ look for ceratopsians thanks to a picture in David Lambert’s 1983 Collins Guide to Dinosaurs.

Caption: McLoughlin (1979) reconstructed several ceratopsians in additional to Triceratops, including non-ceratopsids like Psittacosaurus and Protoceratops, and ceratopsids like Chasmosaurus (at left) and Styracosaurus (at right). Image: McLoughlin (1979).

While these reconstructions are improbable for the reasons mentioned above, they can also be considered illogical because they would mean that the frill – and hence the entire head – was virtually immobile, and held firmly in place against the shoulders. The projecting epoccipitals, knobs and other structures on the frill surfaces and edges also show that the frill cannot have been submerged in soft tissue. Furthermore, the frills of some ceratopsid ceratopsians – notable examples include Pentaceratops and Agujaceratops – are so long, and so strongly inclined upwards relative to the long axis of the skull, that there can be no doubt that they stood well up above the shoulders in life, and cannot have been ‘tied’ to the thorax by soft tissues. While some modern lizards sport bony frills that are connected to the thorax by skin webs, the frills in these animals are narrow, sheet like structures. Certain chameleons do have wider, more ceratopsian-like frills, and these are not connected by soft tissue to the animal’s back.

Caption: A McLoughlinesque Triceratops as redrawn from 1983 Collins Guide to Dinosaurs.

I don’t know that McLoughlin’s 1979 idea was ever considered interesting enough that it resulted in anyone copying it, let alone running with it: I think it was immediately realised that it was a non-starter and not worthy of detailed critique or analysis. Here we hark back to my comments – made in the recent dicynodont article – on how people opt to respond to heterodox claims in the literature; they mostly just ignore them. But, whatever, it was an interesting, unusual take on what these dinosaurs were like. And that’s where we’ll end.

UPDATE (added 23rd November 2020): as mentioned in the article, the frills of some ceratopsians are so long and so big, that draping them in huge amounts of jaw musculature would surely result in a highly impractical appearance, to say the least. Inspired, Henry Peihong Tsai did exactly this - his aim being to reconstruct a McLoughlinian Titanoceratops. World, I give you….

Caption: courtesy of Henry Peihong Tsai, used with permission. Henry adds: “I’ve thrown in the Japanese characters for “menacing” sound effect (“go go go go”), as well as some inaccurate elephantine feet for good measure”.

For previous TetZoo articles on ceratopsians, see…

Zuniceratops and the early acquisition and alleged dimorphism of ceratopsian brow horns, April 2009

Ceratopsian dinosaurs: cheeky or beaky?, April 2009

Greek-nosed first-horned face and the ‘bagaceratopids’, April 2009

Ryan et al.'s New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: a review, April 2012

Dinosaurs and their exaggerated structures : species recognition aids, or sexual display devices?, April 2013

Hot News From Planet Archosaur, October 2015

The Ridiculous Nasal Anatomy of Giant Horned Dinosaurs, November 2016

The Supracranial Sinus of the Horned Dinosaur Skull, July 2017

Refs – -

Dodson, P. 1996. The Horned Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

McLoughlin, J. C. 1979. Archosauria: A New Look at the Old Dinosaur. Penguin Books, London.