Among my several recently published books is Ancient Sea Reptiles: Plesiosaurs, Ichthyosaurs, Mosasaurs & More, first released by the Natural History Museum in 2022…

Caption: a third edition at left, published 2025, and a first edition, published 2022, at right. I appreciate that it might be hard to tell them apart from these photos. Images: Darren Naish.

A slightly modified second edition appeared in 2023, this one including tweaks to the section on pachyophiid (or simoliophiid) snakes and thalattosuchian sea crocs. But the big news is that a third edition – the first softback – came out in 2025, and that’s why we’re here today.

Yes, a third edition! This one includes a substantial number of changes, because oh boy does the field of Mesozoic marine reptiles move fast and often. I was extremely happy to have the opportunity to make these numerous updates, and here we’re going to look at some of the more interesting of them in brief, cursory fashion. I’ll note to start with that the third edition includes minor grammatical tweaks that both correct typos and just make for easier reading overall. I never fail to be amazed by my ability to overlook typots and somehow overlook poorly contruicted prose, but what writer doesn’t thing this way or at least I assume so anyway and it’s amazing how much in the popular literature exists bad writing.

Caption: the UK is a provincial little archipelago nation, located on the maritime fringes of a vast continental landmass. But it has a surprisingly complex and interesting Mesozoic sedimentary record, and an extremely rich marine reptile fossil record. Here are just a few Mesozoic marine reptile fossils I’ve seen in person. Clockwise from upper left: a cryptoclidid plesiosaur at Oxford University Museum of Natural History, the partial rostrum of what’s probably a new taxon of geosaurine thalattosuchian in a private collection, a temnodontosaur at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, and a thalassophonean pliosaurid at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery. Images: Darren Naish.

A tweak I made to the anatomy section, and specifically to the text concerning dorsal fins, concerns the Japanese mosasaur Megapterygius. As was widely reported when this animal was first published, the form of its dorsal vertebrae led to the suggestion that it might have had a dorsal fin. That’s interesting if you’ve paid attention to artistic reconstructions of mosasaurs, since there’s a history of people making speculations about the presence of such structures, not because specific evidence exists but more because it feels about right in view of how aquatically adapted these animals were. I’m not saying that this is a good argument (in fact, it’s an especially bad one) but we can’t pretend that it doesn’t exist.

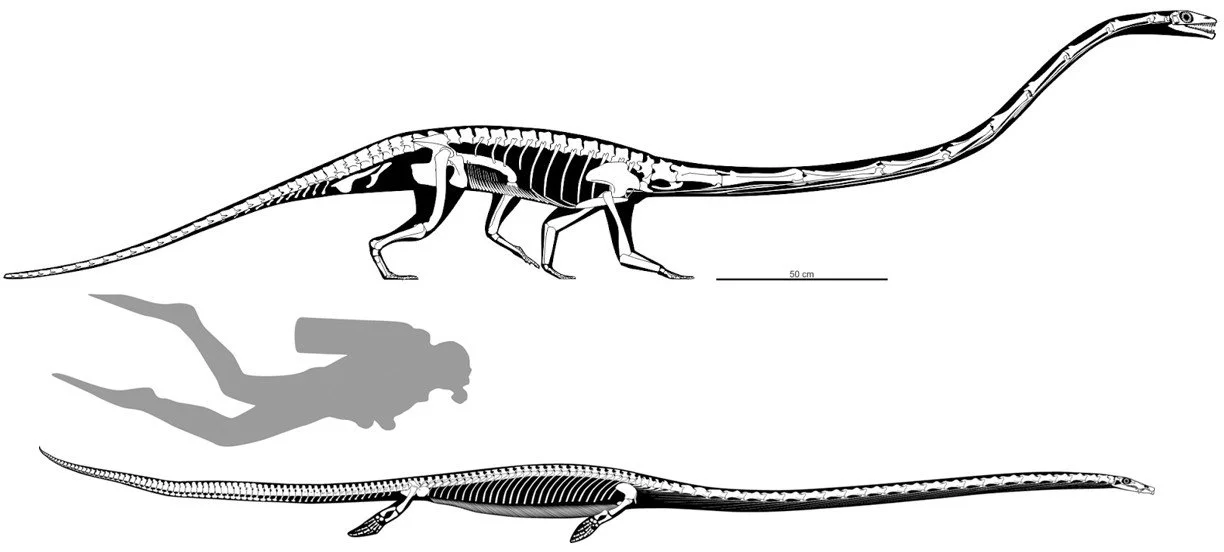

Tanysaurians united. Moving to the section on (mostly) Triassic marine reptiles, some good quantity of new work has appeared on Tanystropheus and its relatives. When I wrote the first edition back in 2021/2022, the two relevant groups – one anchored on Tanystropheus and one on Dinocephalosaurus – were regarded as close but not as a clade that excluded other protorosaur-type archosauromorphs.

Caption: the two most famous tanysaurians. Tanystropheus is above, here shown as a digitigrade animal well adapted for terrestrial walking; Dinocephalosaurus is below, reconstructed as a highly aquatic swimmer with flipper-like limbs. The radically different ways in which members of both lineages evolved their incredibly long necks are obvious. Images: (c) Mark Witton; Spiekman et al. (2024a).

A 2024 study found that both groups should be united within a clade, named Tanysauria. In addition, the recovery of the German tanysaurian Trachelosaurus as a close relative of Dinocephalosaurus requires Dinocephalosauridae to be subsumed into Trachelosauridae (Spiekman et al. 2024b). Several newly recognised tanysaurians have been published since the first edition of the book appeared.

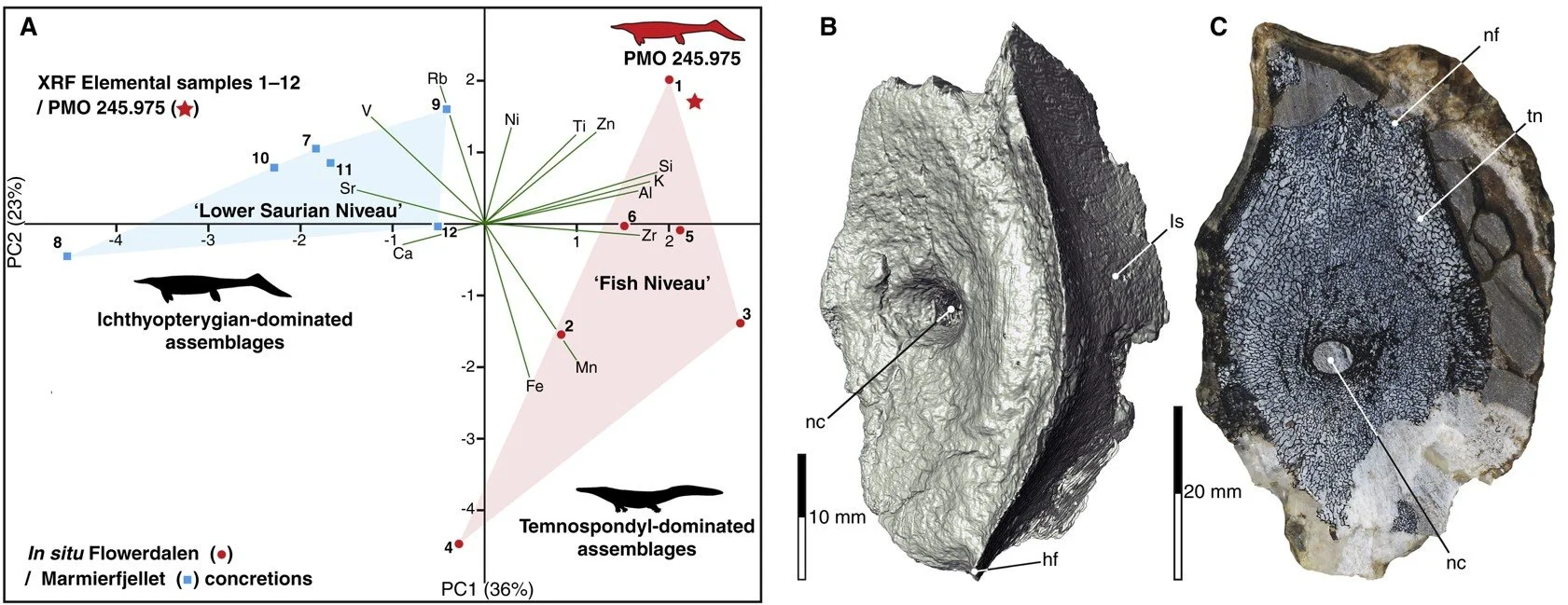

Triassic ichthyosaurs and goodbye Nasorostra. Among the biggest area of change concerns Triassic ichthyosaurs, both because notable discoveries have been made and because new ideas have been put forward on phylogeny and taxonomy. To start with, I had to work in Kear et al.’s 2023 publication on a caudal vertebra from a reasonably large, Early Triassic ichthyosaur from Spitsbergen. This comes from sediments deposited just a few million years after the end of the Permian and perhaps indicates extremely rapid evolution within the group during the very earliest years of the Triassic, or an origin in the Permian, or both (Kear et al. 2023).

Caption: the surprisingly old Early Triassic ichthyosaur caudal vertebra PMO 245.975 from Spitsgerben, shown at right, demonstrates the presence of these animals very shortly after the giant end-Permian extinction. The plot at left shows how the specimen was demonstrated via geochemistry to belong to the ‘Fish Niveau’ and thus to have originated in-situ from this stratigraphically old unit, and not to have eroded out of a younger unit higher in the sequence. Image: Kear et al. (2023).

Then there are the nasorostrans. Back in 2016, Jiang et al. proposed that two Triassic members of the ichthyosaur lineage from China – Cartorhynchus and Sclerocormus – belonged to a distinct lineage that they named Nasorostra. They regarded nasorostrans as close to, but outside of, Ichthyosauria… or Ichthyopterygia. Both names are in use and regarded as synonymous by some, but as pertaining to different clades by others, sigh (Jiang et al. 2016). It’s since been argued that nasorostrans are not a distinct group but actually belong within Omphalosauridae (Qiao et al. 2022), an Early and Middle Triassic group generally (albeit not universally) regarded as ichthyosaurs… or ichthyopterygians… and best known from Spitsbergen, central Europe and the USA.

Omphalosaurids are very weird animals. Their super-numerous button-like teeth indicate a shellfish diet while bone histology is strongly suggestive of a pelagic lifestyle, not a coastal one as was originally suggested for Cartorhynchus. Given that these animals look to be extremely early-diverging within Ichthyosauria/Ichthyopterygia, this apparent pelagic specialisation again has implications for ichthyosaur… or ichthyopterygian… early evolution and specialisation. If this is right, it also means that reconstructions showing Cartorhynchus as amphibious (like the one by Mark Witton included within the book) are possibly in error. None of this, of course, is the last word on the animals concerned. I published on Cartorhynchus back when it was brand new: go here if you want a refresher.

The stupendously huge Ichthyotitan, named in 2024, is now discussed in the shastasaur section. And text on other new ichthyosaur taxa – like Magnipterygius from the Early Jurassic of Germany and Argovisaurus from the Middle Jurassic of Switzerland – has also been added.

Caption: at left, life reconstruction of the gargantuan shastasaurian ichthyosaur Ichthyotitan. At right, images of the holotype surangular (A and C) and a referred specimen (B and D) of Ichthyotitan, from Lomax et al. (2024). This is a single bone that formed the rear part of the mandible yet that scale bar is 50 cm. Images: (c) Gabriel Ugueto; Lomax et al. (2024), CC BY 4.0.

Sauropterygians and thalattosuchians. The world of sauropterygians – that’s the giant group that includes plesiosaurs and their relatives – is extremely active right now, both in terms of new animals from the Triassic and new plesiosaurs from the Jurassic and Cretaceous. I didn’t change the relevant sections on those animals that much… but I’m definitely going to need to modify some things for the next one. A lot has happened in Early and Middle Jurassic plesiosaurs in particular. I also really want to work in a discussion of the fantastic long-necked polycotylid Serpentisuchops, named in 2022 (Persons et al. 2022).

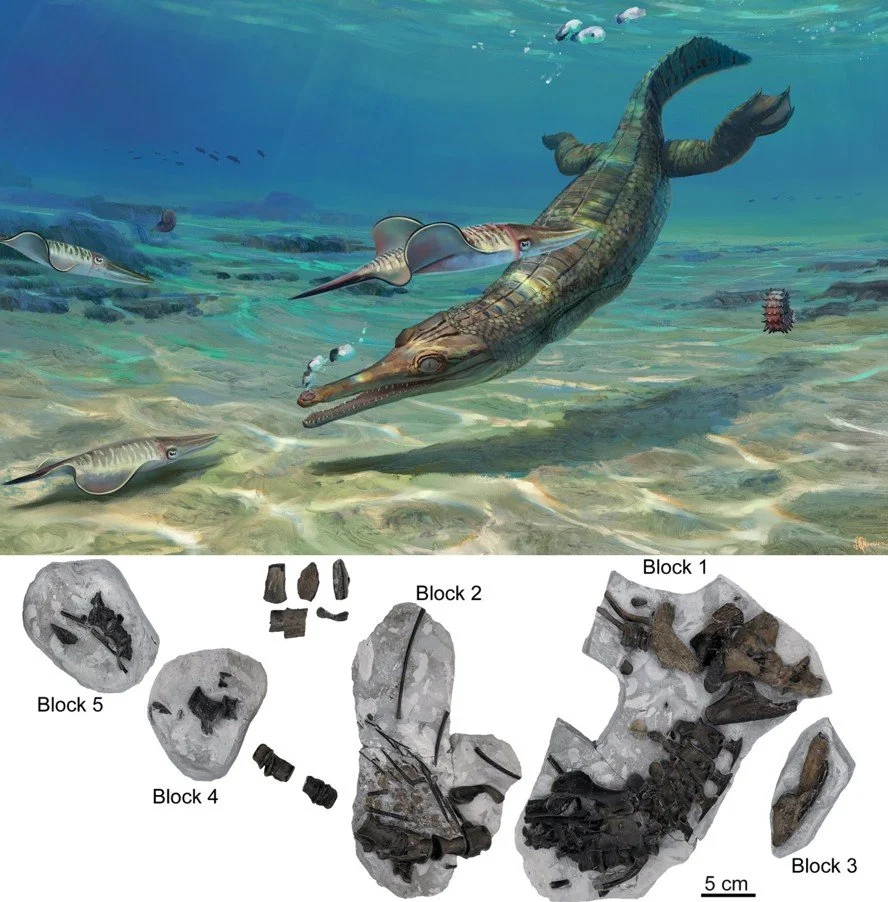

Of thalattosuchians – sea crocs – an area that’s seen activity since the publication of the first and second editions concerns newly published very early members of the group. Among these is Turnersuchus from the English Lower Jurassic, named in 2023 (Wilberg et al. 2023), a Moroccan animal reported in 2023 (Benani et al. 2023), and assorted possibly even older remains from the Dorset coast and Lincolnshire in England described in 2024 (Young et al. 2024).

Caption: the Early Jurassic thalattosuchian Turnersuchus, an archaic member of the group outside the teleosauroid + metriorhynchoid clade. The specimen is on show at Lyme Regis Museum. Note from the scale bar that it’s not a large animal. Images: Júlia d'Oliveira; Wilberg et al. (2023).

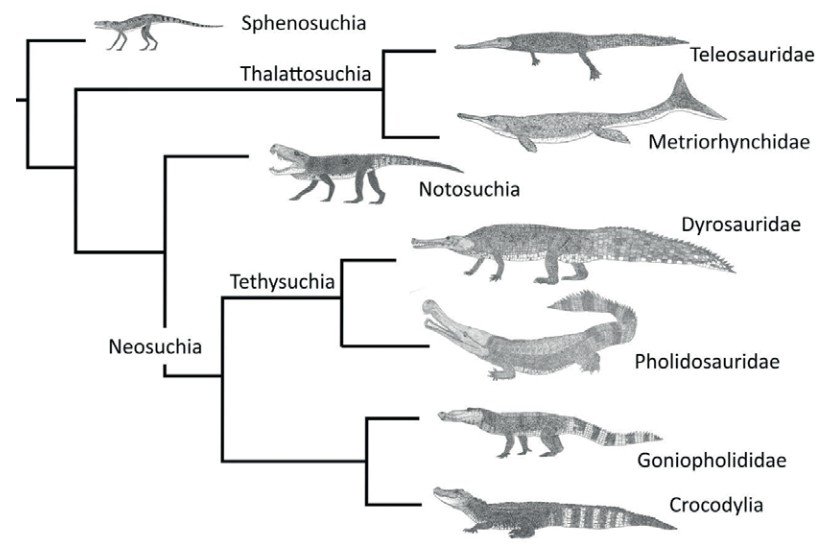

The great age of these various specimens is in keeping with views that thalattosuchians are not part of the great clade Neosuchia and that they originated comparatively early within crocodylomorph history, maybe during the latest Triassic (Young et al. 2024). I did my best to emphasize this point within Ancient Sea Reptiles but a complication I always butt into is that the crocodylomorph groups surrounding thalattosuchians in phylogeny are all but unknown outside the specialist community and I haven’t yet done any popular-level writing that covers these groups. Oh to do a similar book that covers the full diversity of fossil crocodylomorphs…

Caption: views on where thalattosuchians belong within Crocodylomorpha have undergone a major change over the past few decades. Recent studies have mostly found them to be well away from Neosuchia – the mostly Cretaceous and Cenozoic group that has extant representatives – and to instead be placed among various archaic lineages that are both obscure and poorly known in terms of their early history. Image: Darren Naish.

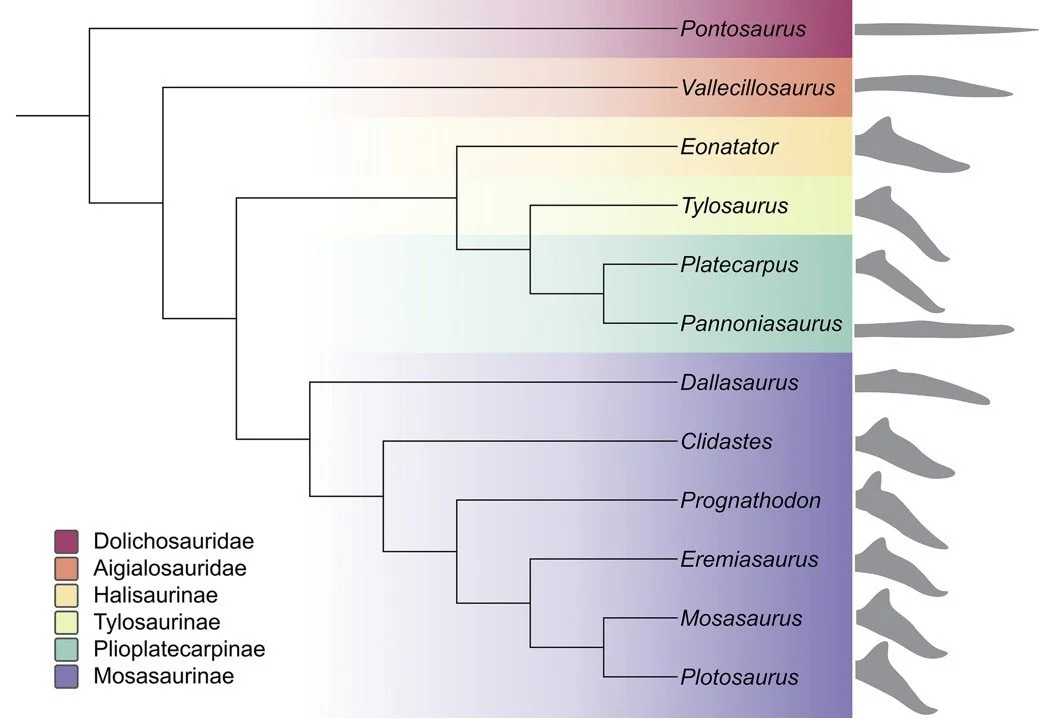

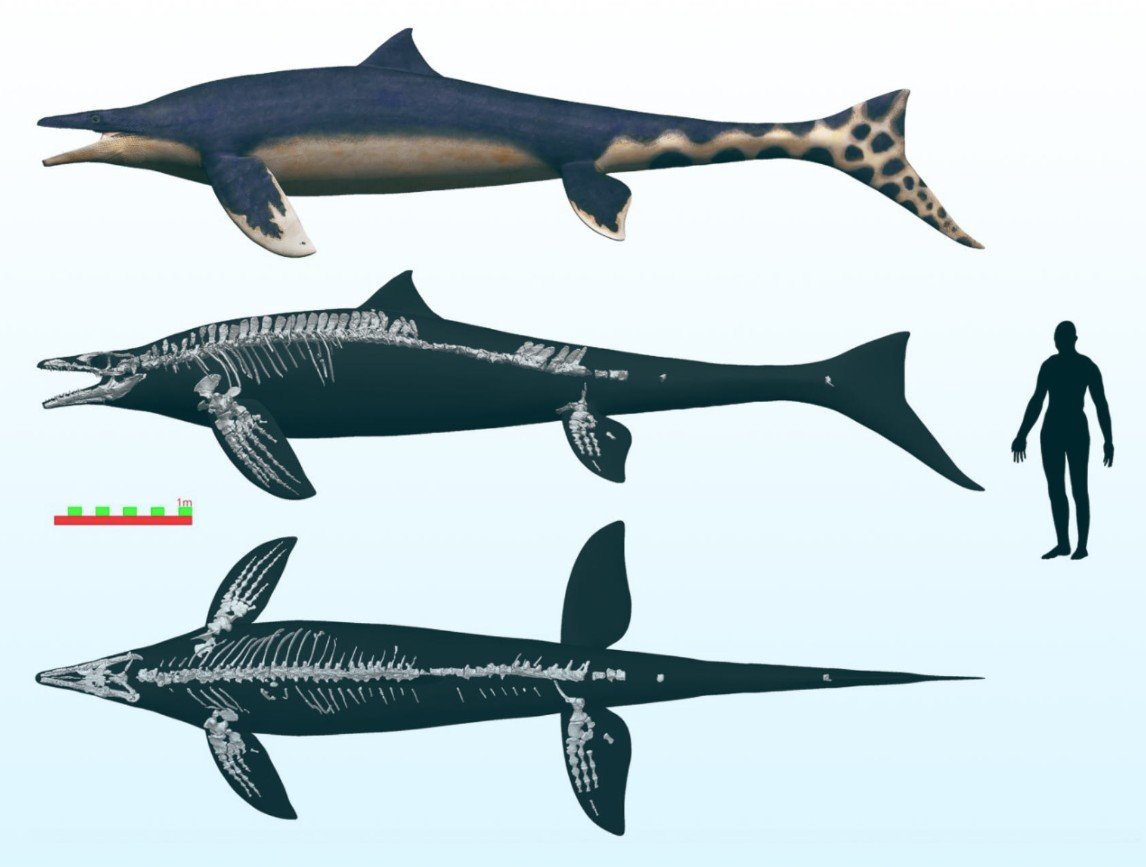

Mosasaurs in the 2020s. It’s well known that mosasaur research is currently highly active, so much so that updates and changes are certainly going to be required between editions of Ancient Sea Reptiles. Despite over the phylogenetic position of mosasaurs within squamates continues and the view that the different mosasaur lineages might have evolved their pelagic specialisations independently of one another – a view I endorsed in the book – has recently been bolstered by work on circulation patterns in the braincase (Polcyn et al. 2023) and variation in tail fluke anatomy (Song & Lindgren 2025). These studies (and others) differ in how they reconstruct the relationships between the main mosasaur clades (tylosaurines might be outside the Russellosaurina + Mosasaurinae clade, halisaurines might be closer to Russellosaurina than to Mosasaurinae), so the cladogram I featured in Ancient Sea Reptiles might need an update in future.

Caption: mosasauroid tail fluke anatomy plotted on a cladogram, from Song & Lindgren (2025). The distribution of these flukes (or fins) on the cladogram indicates two or more independent evolutions of the highly modified, heterocercal tail tip most obvious in tylosaurines and mosasaurines. Image: Song & Lindgren (2025).

The several new taxa named from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco, and disputes over their validity and where they fit within mosasaur evolution, of course required changes here and there in the mosasaur section. Megapterygius from Japan, a mosasaurine, gets a new discussion here as well (and a new illustration).

Caption: the mosasaurine Megapterygius (which I perpetually confuse with the ichthyosaur Magnipterygius), reconstructed with a dorsal fin that may or may be evidenced by the anatomy of the dorsal vertebrae. Image: Takumi, from here.

Ancient Sea Reptiles includes a chapter on sea turtles as well, the main change for the third edition involving what I wanted to say about the geographically widespread, superficially leatherback-like Allopleuron. This was a remarkably successful turtle that persisted from the Cretaceous until the end of the Oligocene. One change I’ll make for the next edition concerns a fossil sea turtle nest from Upper Cretaceous sediments of the USA, but more on that in future.

To see the changes be sure to get the new edition yourself: you can buy it from the publisher here, or directly from me here (and I’ll sign it if you tell me what to write). Needless to say, the fact that we’ve gone to third edition already is great news and demonstrates the popularity of the book, and of the whole subject in general. There are – finally! – a couple of other books now that also cover Mesozoic marine reptiles (like Bardet et al.’s Ocean Life in the Time of Dinosaurs, published in English in 2023) but Ancient Sea Reptiles very clearly remains the best on the market. Ok, I might be biased.

One more thing: Ancient Sea Reptiles might be very relevant to an event happening in 2026. More on that in due time.

Caption: buy Ancient Sea Reptiles from the publishers here, and directly from me here.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on Ancient Sea Reptiles and the animals it covers, see…

The skin of ichthyosaurs, September 2008

Who made the giant Jurassic sea-floor gutters?, December 2009

Prediction confirmed: plesiosaurs were viviparous, August 2011

Can’t get me enough of that sweet, sweet Temnodontosaurus, January 2014

Plesiosaur Peril — the lifestyles and behaviours of ancient marine reptiles, March 2014

Ancient Marine Reptiles Had Absurd, Complex Nostrils, July 2014

‘Proto-Ichthyosaur' Sheds Light on Fish-Lizard Beginnings, November 2014

The Unique and Efficient 4-Flipper Locomotion of Plesiosaurs, August 2017

The Fall and Rise of Protoichthyosaurus, October 2017

The Ichthyosaurs of the Kimmeridge Clay, March 2021

History of the Iraqi Ichthyosaur, April 2021

Ancient Sea Reptiles Is Out Now, February 2023

Refs - -

Benani, H., Nehili, A., Ouzzaouit, L. A., Jouve, S., Boudad, L., Masrour, M., Jalil, N. & Arrad, T. Y. 2023. Discovery of the teleosauroid crocodylomorph from the early Jurassic of Chaara cave, Middle Atlas of Morocco. Journal of African Earth Sciences 198, 104804.

Jiang, D.-Y., Motani, R., Huang, J.-D., Tintori, A., Hu, Y.-C., Rieppel, O., Fraser, N. C., Ji, C., Kelley, N., P., Fu, W.-L. & Zhang, R. 2016. A large aberrant stem ichthyosauriform indicating early rise and demise of ichthyosauromorphs in the wake of the end-Permian extinction. Scientific Reports 6, 26232.

Spiekman, S. N. F., Ezcurra, M. D., Rytel, A., Wang, W., Mujal, E., Buchwitz, M. & Schoch, R. R. 2024b. A redescription of Trachelosaurus fischeri from the Buntsandstein (Middle Triassic) of Bernburg, Germany: the first European Dinocephalosaurus-like marine reptile and its systematic implications for long-necked early archosauromorphs. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology 143, article 10.

Wilberg, E. W., Godoy, P. L., Griffiths, E. F., Turner, A. H. & Benson, R. B. J. 2023. A new early diverging thalattosuchian (Crocodylomorpha) from the Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian) of Dorset, U.K. and implications for the origin and evolution of the group. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 42, e2161909.