Yes, more unusual takes on ceratopsians; let’s see where this goes…

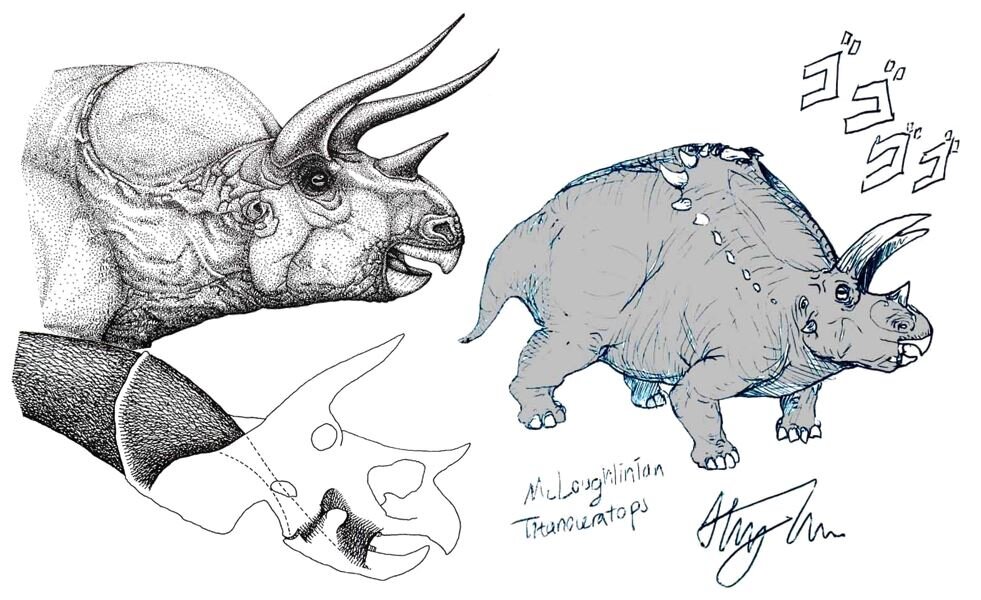

Caption: ‘alternative’ ceratopsians from last time. Images: John McLoughlin; Henry Peihong Tsai.

The idea that the bony frills of ceratopsian dinosaurs – Triceratops and its many kin – might have been deeply submerged in a mass of hyperthickened, hypertrophied, hyperelongate jaw, neck and back musculature was put out there in John McLoughlin’s 1979 book Archosauria: A New Look at the Old Dinosaur. The idea is a non-starter, no-one ever really took it seriously, and it doesn’t work for a list of reasons. And you’ve heard all this before; it was the topic of the previous article.

Curious, counter-intuitive and novel takes on the life appearance of extinct animals alway incite interest, and I especially like it (I can’t help but like it) when they result in the creation of curious and new artwork. You should have seen Henry Peihong Tsai’s McLoughlian Titanoceratops in the previous article (oh, and there is again, above). I like it a lot, but I put it that an even more McLoughlian Titanoceratops would actually look like my version here… (though I’m happy to admit that this reconstruction leans too heavily on the idea that Titanoceratops was similar to Pentaceratops in frill structure, a position based on the initial identification of the relevant specimen as an extra-big Pentaceratops. I actually wrote about the specimen back in 2007).

Caption: another McLoughlian ceratopsian. I feel ashamed. Image: Darren Naish.

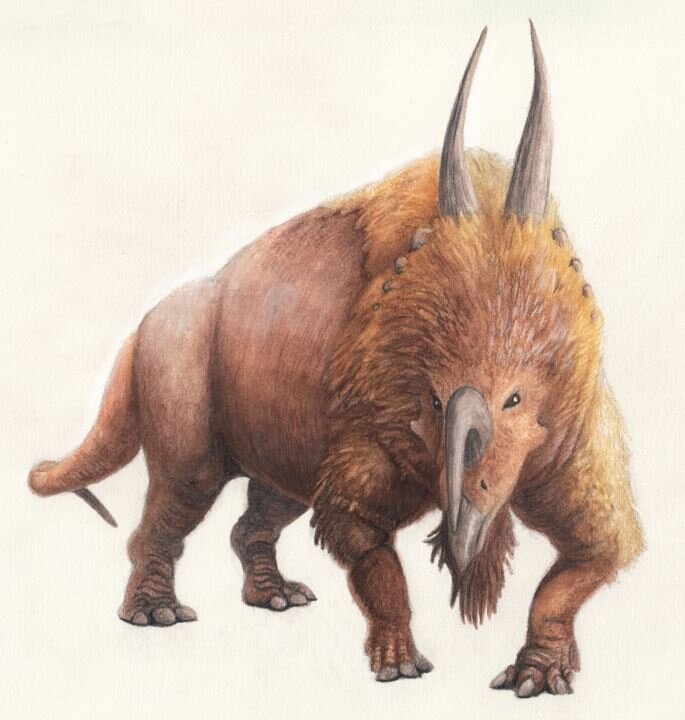

Emily Willoughby was also inspired and produced this (… below) amazing reconstruction, it being a deliberate, whimsical effort to produce a hypothetical ‘buffalo ceratopsian’…

Just to be clear: this is not meant to be a scientific or rigorous effort to portray a ceratopsian in life, it is instead a deliberate effort to play along and portray a McLoughlian ceratopsian from an alternative universe. It’s a fun concept.

Caption: a hypothetical ‘buffalo lizard’ by Emily Willoughby, used with permission.

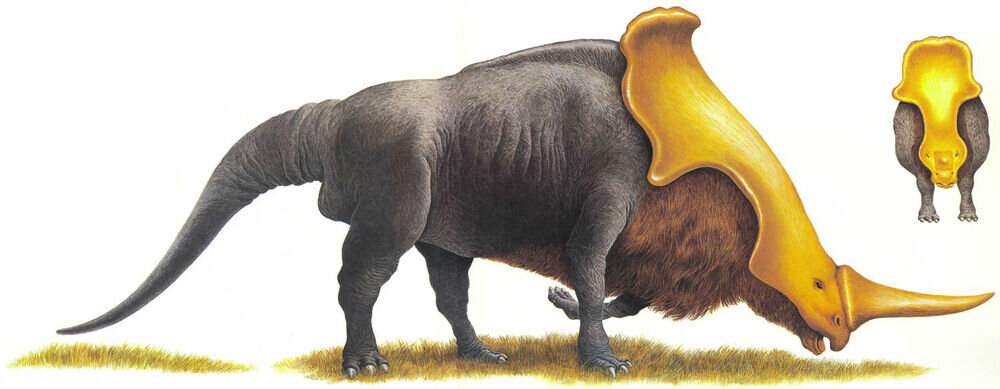

But it’s also a very interesting one, since I immediately see it as being connected to a few other things worth mentioning. I think, you see, that there’s a tendency, an expectation, to imagine ceratopsians – and other quadrupedal dinosaurs too – as having some sort of latent capacity to evolve in a ‘buffalo-backed’, hump-shouldered direction. Exhibit A is one of the most spectacular beasts of Dougal Dixon’s alternative timeline SpecZoo work of 1988, The New Dinosaurs: the Monocorn Monocornus occidentalis, a herd-dwelling grazer that has a massive, keratin-covered face and frill, a shaggy mane and tall, immensely muscular shoulders that give it a great hump over the front of the chest (Dixon 1988).

Caption: Dougal Dixon’s Monocorn, as illustrated by Philip Hood in Dixon (1988).

Among ‘real timeline’ dinosaurs, it would be remiss not to mention Jack Bailey’s study of 1997 in which those dinosaurs with extra-long neural spines (Spinosaurus and Ouranosaurus in particular) were suggested to have humps rather than sails. Bailey’s (1997) argument was that the neural spines of these dinosaurs are thick and chunky relative to those of the tall-spined synapsids Dimetrodon and Edaphosaurus (which he accepted as sail-backed), and that the dinosaur neural spines – expressed as a percentage of total trunk depth – weren’t as tall as those of the synapsids, but instead similar to those of tall-spined mammals, like bison. The argument was, essentially, that the tall neural spines of these dinosaurs look more like “attachment sites, not for a sail, but for large muscles and ligaments that formed a broad hump” (Bailey 1997, p. 1129).

Caption: (1) Spinosaurus and (2) Ouranosaurus as reconstructed (by R. E. Johnson) for Bailey’s 1997 paper. It was argued that these humps might function as thermal shields or as fat storage sites. Image: R. E. Johnson/Bailey (1997).

A few accompanying life reconstructions (produced by R. E. Johnson) depicted Spinosaurus and Ouranosaurus as ‘buffalo-backed’ dinosaurs in Bailey’s paper. The record shows that at least a few palaeontologists thought that Bailey’s idea wasn’t a bad one, or at least one worthy of consideration, as demonstrated by this 2011 article by Riley Black and a few commentary pieces here and there (e.g., Anon 1998). I, personally, didn’t think it correct, for reasons we’ll get to in a moment.

Of Crystal Palace and Altispinax. It’s also appropriate here to mention the Crystal Palace Megalosaurus of the early 1850s, another dinosaur very plainly given a ‘buffalo back’, even though its early appearance in the public sphere means that it didn’t feed into the modern zeitgeist. Those with good memories might recall my argument (Naish 2010) that the megalosaur was given a shoulder hump because Benjamin Hawkins – and his supposed advisor, Richard Owen – identified the tall-spined vertebrae of the British Wealden theropod Altispinax as pertaining to the anterior thoracic region of Megalosaurus (Naish 2010).

Caption: the Crystal Palace Megalosaurus, photographed to emphasise its massive shoulder hump, as it looked when I took this photo in 2018. Since then, the model has of course been severely damaged by a person who hung from the lower jaw and then managed to rip most of the face off. Image: Darren Naish.

It is true that Owen (1855) regarded the Altispinax vertebrae – Megalosaurus vertebrae to him – as being from the shoulder region (he stated “The extraordinary size and strength of the spines of these anterior dorsal vertebrae, indicate the great force with which the head and jaws of the Megalosaurus must have been used” (Owen 1855, Tab. XIX caption)). But is it true that this identification influenced the look of the Crystal Palace Megalosaurus? It seemed to me like a reasonable guess, but it’s a guess I made before reading Owen’s guidebook to the Crystal Palace models (a piece of literature unavailable to me when I wrote that 2010 article). Therein, we find no mention whatsoever of any contribution made from Cretaceous fossils, no hint that the Altispinax vertebrae had any role. Mark Witton – who’s been doing a lot of research on the prehistoric animals of Crystal Palace for a current project – confirms that this speculation is likely not correct, and that the decision to add a shoulder hump to the Megalosaurus was not inspired by Altispinax. Ok, fair enough. Funny coincidence though.

Caption: at left, NHMUK R1818, the holotype dorsal vertebrae of Altispinax dunkeri… formerly Becklespinax altispinax (yes, I’m following Michael Maisch’s 2016 argument that A. dunkeri is the right name). At right, Owen’s 1855 depiction of the same specimen: you’ll note that there are various differences between the specimen and the illustration. Images: Natural History Museum; Owen (1855).

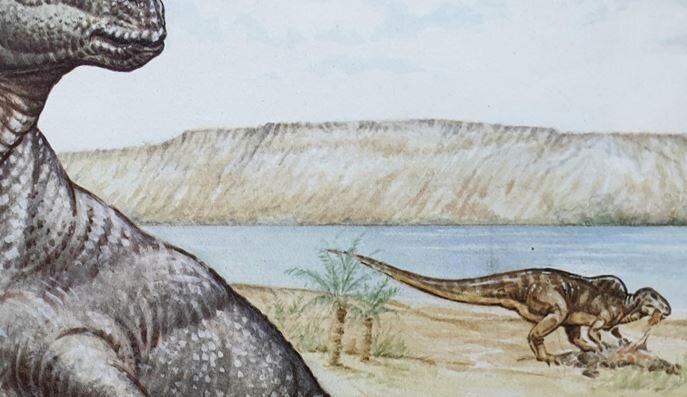

As it happens, this exact idea (that the Altispinax vertebrae are anterior dorsals and would indeed have resulted in a tall shoulder region) did, however, influence at least one reconstruction: a 1979 painting by Peter Snowball of a Wealden scene (it features most prominently in Alan Charig’s book A New Look at the Dinosaurs). Therein, we see an Altispinax with a shoulder hump (Charig 1979). Though, actually, the animal is distant enough that we can’t tell whether it’s been given a narrow sail or a wide hump. The interplay of light and shadow makes me think it’s meant to be more of a sail. Whatever, it’s not especially relevant to the buffalo-backed themed.

Caption: a detail from Peter Snowball’s 1979 Wealden scene (featured in Charig 1979), showing the theropod Altispinax with a shoulder hump or sail. I think that the original of this painting is in the Natural History Museum, London. Image: (c) Peter Snowball/Natural History Museum.

Altispinax aside, these various artistic and scientific renderings show that people have – on occasion (albeit not that many) – imagined dinosaurs as having the capacity to be, or become, ‘buffalo-backed’. But is this really so?

‘Buffalo backs’ are not for dinosaurs… probably. Being or becoming ‘buffalo-backed’ seems a very ‘mammalian’ way of doing things. Unlike mammals, dinosaurs tend to be heavy and muscular in the hips, hindlimbs and tail. Based on birds, crocodylians and lizards, we can speculate with some degree of certainty that these regions (above the hips and around the base of the tail in particular) would also have served as their main sites of fat storage (abdominal fat storage would also have been present, and areas with masses of fat could also include the sides of the neck, as is the case in some lizards and crocodylians). What this means overall is that a muscular, plump dinosaur should be expected to be ‘hip heavy’, not ‘shoulder heavy’. If you were to imagine a dinosaur evolving a big fat storage sites – big enough to form a hump – it would most likely be over the hips or tail base.

Having said all that, some quadrupedal dinosaurs had – so it’s been claimed – sufficiently elevated shoulder regions and anterior thoracic vertebrae to indicate that they had a low muscular ‘peak’ over the shoulder region. Palaeoartist Greg Paul has referred to these as withers, specifically for brachiosaurid sauropods and chasmosaurine ceratopsians (Paul 1987). If chasmosaurines have ‘withers’, could it be that we do really have an evolutionary potential here for a ‘buffalo back’? Well… the feature is incredibly subtle in those chasmosaurines suggested to have it (Chasmosaurus russelli is the main contender), and careful inspection shows that the tallest-spined vertebrae are actually at about the mid-point of the thorax, not over the shoulder region as they are in bison. In a speculative scenario where these spines became enlarged, you’d end up with a chasmosaurine that has an elevated back, not an elevated, buffalo-like shoulder region.

Image: mounted skeleton of Chasmosaurus russelli on display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Alberta. Even if some of the vertebrae here have neural spines a bit higher than we might expect, I don’t think there’s any indication that we might get a hypothetical ‘buffalo-backed’ descendant of this animal. Image: Sebastian Bergmann, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

Chameleon backs, not buffalo backs. And if this did happen, would it result in a ‘buffalo back’? The main problem here – again – is that people have been thinking of dinosaurs as too ‘mammalian’, not as sufficient ‘reptilian’. Tall neural spines in reptiles tend to be more to do with narrow sails, not thick, wide humps. This is why I never bought Bailey’s argument of 1997: for all his argument that the tall neural spines of Spinosaurus, Ouranosaurus and so on look like bison neural spines, the fact is that they also look superficially like the neural spines of certain chameleons, basilisks and water dragons.

Long-term readers might recall me saying way back in 2010 (and probably earlier) that the tall neural spines of various theropods and other dinosaurs were more likely analogues of the tall spines present in various living lizards, and – like those of the relevant lizards – were more to do with supporting sails than humps. I actually managed to get hold of a sail-backed chameleon skeleton at one point and began work on a paper comparing chameleon neural spines to those of dinosaurs… but then Ibrahim et al. (2014) appeared, which specifically compared spinosaurid neural spines with those of chameleons and hence effectively made the point well enough.

Caption: some chameleons - like this Jackson’s chameleon Trioceros jacksonii - have elongate dorsal neural spines that are similar to those of tall-spined dinosaurs, and they support sails. Not humps. Jackson’s chameleon is not an especially tall-spined species, some Trioceros species are more sail-backed. Images: Darren Naish.

If we look across dinosaurs in general, we see that they’re prone to the evolution of tall, mid-line ridges and crests formed of elevated neural spines. This can be readily observed in ceratosaurid, spinosaurid and allosauroid theropods, in Deinocheirus, diplodocoids, some iguanodontians like Ouranosaurus and seemingly therizinosaurs like Nothronychus, in some stegosaurs, and in some lambeosaurine hadrosaurs. Sure, there were muscles and ligaments (and doubtless fat as well as skin) attached to these spines which would have meant that – in cross section – the ridges were broad at their bases, but we should be thinking of reptile-like ridges and sails as the default, not humps. A non-trivial point worth mentioning is that those mammalian humps supported by tall neural spines (like those of bison) are an open-country grazing adaptation probably linked to an efficient ‘rocking’ gait (Guthrie 1990). In other words, they evolved in a context that isn’t applicable to any of the dinosaurs that have been suggested to be buffalo-backed.

Caption: Guthrie (1990) argued that the shoulder humps of living mammals mostly correlate with adaptation to a grazing life in open habitats, and function in increasing efficiency by allowing greater stride length.

And that’s where we’ll end things. This was meant to be a brief take of a few hundred words – basically saying “look, new art!” – but I guess it took on a life of its own.

For previous TetZoo articles relevant to the issues mentioned here, see…

Pentaceratops: that’s quite the skull, September 2007

Of Becklespinax and Valdoraptor, October 2007

Concavenator: an incredible allosauroid with a weird sail (or hump)... and proto-feathers?, September 2010

By the Horns of Trioceros, the Casque of Calumma, the Brood of Bradypodion--Chameleons, Part 2, February 2016

Up Close and Personal With the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, December 2018

A Very Alternative View of Horned Dinosaur Anatomy, Revisited, November 2020

Refs - -

Anonymous 1998. Dino fins more like humps? Science 279, 1139.

Bailey, J. B. 1997. Neural spine elongation in dinosaurs: sailbacks or buffalo-backs? Journal of Paleontology 71, 1124-1146.

Dixon, D. 1988. The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution. Salem House Publishers, Topsfield, MA.

Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P. C., Dal Sasso, C., Maganuco, S., Fabri, M., Martill, D. M., Zouhri, S., Myhrvold, N. & Lurino, D. A. 2014. Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur. Science 345, 1613-1616.

Naish, D. 2010. Pneumaticity, the early years: Wealden Supergroup dinosaurs and the hypothesis of saurischian pneumaticity. In Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343, pp. 229-236.

Owen, R. 1855. Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck formations. Part II. Dinosauria (Iguanodon). (Wealden). Palaeontographical Society Monographs 8, 1-54.

Paul, G. S. 1987. The science and art of restoring the life appearance of dinosaurs and their relatives - a rigorous how-to guide. In Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present Vol. II. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and London), pp. 4-49.