Regular readers of this blog will almost certainly be aware of what are most sensibly termed sea monster accounts. Throughout recorded history, and throughout the seas and oceans of the world, people claim to have observed gigantic, anatomically remarkable creatures that did not, at first sight, match any animal species known to science.

Caption: sea monsters real and imagined, an old illustration done as a prototype for a mural. Image: Darren Naish.

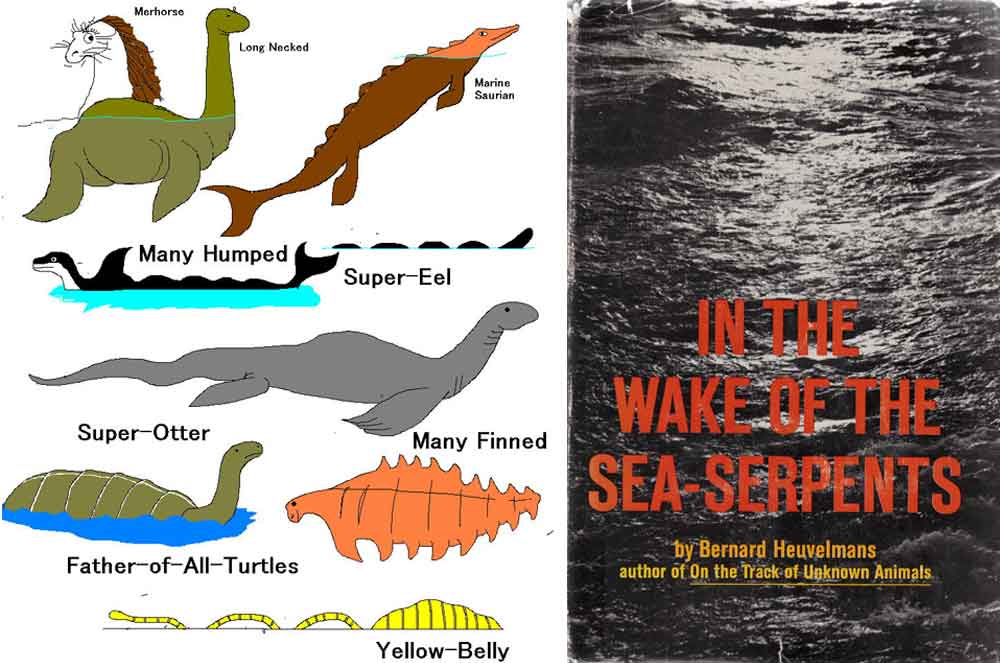

The view favoured by cryptozoologists (people who investigate ‘mystery animal’ reports) has mostly been that these accounts describe real encounters with real animals, and animals that are scientifically new, exciting and surely worthy of recognition. I’ve written before about the work of Bernard Heuvelmans and his followers and colleagues (see the links below), most recently in my 2017 book Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017). Heuvelmans (1968) argued that sea monster reports could be sorted into nine categories, and thus that (at least) nine new species of gigantic, sea-going vertebrate species were out there and awaiting discovery.

Caption: in the most influential book ever written on sea monsters, Bernard Heuvelmans argued for the existence of nine distinct sea monster types, illustrated at left by Cameron McCormick. It was thought for a while that Heuvelmans (1968) had done a good job in discovering a valid biological signal in sea monster reports. But… no. Images: Cameron McCormick, Heuvelmans (1968).

Alas, this view is mostly regarded as naïve by the majority of biologists and other scientists. Isn’t it more likely that ‘sea monster reports’ are confused or embellished descriptions of encounters with known animals or objects, like surface-feeding whales, unfamiliar giant fishes, swimming deer, or masses of weed, floating wood or fishing gear? In recent years, several classic reports have been re-evaluated and argued to variously be confused accounts of skim-feeding sei whales (Galbreath 2015), sea lions and other pinnipeds behaving in unpredictable ways (Naish 2017), whales and turtles tangled in rope (France 2016a, b), whales in a state of sexual arousal (Paxton et al. 2004), and even misidentified pipefishes (Woodley et al. 2011).

Caption: classic sea monsters like this one - the Daedalus encounter from 1848, involving a creature seen off the coast of Namibia in the south-east Atlantic - have often been regarded as inexplicable, and as evidence for the reality of sea monsters. But they might be explainable after all. Image: Illustrated London News, in public domain.

Among those who’ve regarded sea monsters as real and novel animals, there’s a long-running tradition whereby they’re regarded as ‘prehistoric survivors’: as the modern descendants of animals otherwise known only as fossils. This view has been endorsed by cryptozoological authors, but it’s also reflected in sea monster accounts themselves, since eyewitnesses have sometimes likened the creatures they saw to fossil animals they ‘know’ from the popular literature and museum displays. For obvious reasons, such comparisons post-date the scientific discovery of such fossil animals… which raises the question: have descriptions of sea monsters been inspired by people’s knowledge of, or familiarity with, ancient animals known from fossils?

Caption: the cryptozoological literature includes many volumes that discuss sea monster reports, and often interpret them within the ‘prehistoric survivor paradigm’ (or PSP). Image: Darren Naish.

The idea that sightings of sea monsters might have been inspired by people’s knowledge of, or familiarity with, fossils animals is not new but has been made several times over the years. In 1968, American science fiction author and science writer L. Sprague de Camp (1907-2000) proposed that an increasing awareness of plesiosaurs and mosasaurs led to a change in the sorts of sea monsters people claimed to see (de Camp 1968). Rather than seeing ‘sea serpents’, people were instead now seeing (read: claiming to see) animals of non-serpentine form, sometimes described as having large paddles or an elongate neck. So far as we know, de Camp was the first to propose this idea in print. I propose that we call it the ‘plesiosaur effect’.

Caption: long-necked plesiosaurs - this is Mary Anning’s famous Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus of 1824, as described by William Conybeare - became increasingly familiar to the public from the 1820s onwards. Image: in public domain.

For several years now, my colleague Charles Paxton has been compiling a database of sea monster reports. Already, it’s been used to report historic trends and to analyse such things as how far sea monsters were said to be from their witnesses (Paxton 2009). You don’t have to think of sea monsters as real animals awaiting scientific recognition to see the value in this database. For, if sea monsters are hoaxes, quirks of human perception, or misidentifications of known objects, we might still learn a lot by studying where and when they were seen, how far away they were, how long they were observed for, and precisely what witnesses described. A detailed interest in anomalous phenomena does not mean that you endorse the fringe ideas often associated with said anomalous phenomena – an important point all too often missed!

Caption: quite a few sea monsters were likened by their observers to plesiosaurs and other ancient marine reptiles. This rendition shows the monster seen from the Umfuli in December 1893, south of the Canary Islands. Image: in public domain.

By cross-referencing sea monster eyewitness data with information on key dates in the scientific discovery of fossil marine reptiles and the dissemination of knowledge on them, we aimed to test de Camp’s idea. Our study was published this week in Earth Sciences History (Paxton & Naish 2019).

Caption: has an increasing familiarity with Mesozoic marine reptiles - like the various sauropterygians, ichthyosaurs and kin shown here - influenced people’s ideas on their sightings of modern sea monsters? These illustrations are among the many I’ve done for my in-prep textbook, on which go here. Image: Darren Naish.

Incidentally, I had no strong feeling which way the data would go. I like the idea that sea monster reports have a genuine biological signal – in part because I’ve always thought that at least some sea monster accounts surely describe encounters with real unknown animals* – and hence don’t have any important correlation with scientific and cultural events. But… my increasing scepticism about the reality of sea monsters as new species means that I’m also keen on the idea that the monsters we claim to see are very much products of our cultural backgrounds, of our ‘expectant attention’ (that is, we ‘see’ those phenomena we expect to see due to our prior knowledge), and on those stories, scientific discoveries and artistic and literary works that we consider relevant to our lives. Indeed, this premise forms the core to my Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017).

* Those familiar with my publications will know that I’ve published many articles endorsing this viewpoint; take that, true believers who hate me for being a vile, biased, ivory tower sceptic.

Caption: have I ever mentioned the book Hunting Monsters, available from all good digital retailers and in most book stores? Maybe I have. Image: Naish (2017).

So – what did we find? That sea monster accounts do indeed correlate with the scientific discovery of long-necked marine reptiles (as in: plesiosaurs), since necks are explicitly mentioned or described from the 1850s onwards, and sea monsters were specifically likened to ‘plesiosaurs’ by eyewitnesses. Across the same time frame, those sea monsters accounts that describe the animals as serpent-like decline (Paxton & Naish 2019). In other words: yes, there is a ‘plesiosaur effect’.

Caption: some of our graphs (Paxton & Naish 2019). Eyewitnesses increasingly mentioned ‘plesiosaurs’ and the presence of necks throughout the 1800s. Across the same time frame, references to serpent-like features were in decline. Image: Paxton & Naish (2019).

A valid question that might arise at this point concerns public familiarity with the relevant fossil reptiles. The fact that a given fossil animal is ‘known to science’ doesn’t require that it also be ‘known to the public’. We kept this in mind and deliberately paid attention to the appearance of Mesozoic marine reptile fossils in public museum displays, in newspaper articles reporting on those displays, and in popular literature (Paxton & Naish 2019). And we found good indications that the public were aware of, perhaps even comparatively well informed on, animals like plesiosaurs from the 1820s onwards (Paxton & Naish 2019). Numerous specific cases demonstrate our point here, but among those we found especially interesting are a Punch cartoon of 1848 (which shows two inebriated naturalists talking about ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs), and the Crystal Palace models of 1854 (whoops: we say that the Crystal Palace models are at Sydenham, whereas they’re actually in Penge. Sorry).

Caption: this 1848 cartoon, from Punch magazine, indicates some familiarity among the public of the time with fossil animals like ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs. Image: Paxton & Naish (2019).

Does a link between familiarity with fossil marine reptiles and accounts of sea monsters mean that claimed sea monster sightings were not monster sightings at all, but fabrications or hoaxes inspired by this familiarity? Well, maybe. But not necessarily. In supporting the ‘plesiosaur effect’, we’re saying that people were influenced by fossil marine reptiles when interpreting sea monsters, and this remains true whether they saw unusual waves or floating bits of wood or scientifically new giant vertebrate species. Our conclusion is not ‘sea monster accounts were fake all along’.

Caption: Fox News coverage of our research. “Loch Ness”? “Dinosaurs”? “Delusion”? Sigh.

Finally, it’s not surprising that this paper has succeeded in winning broad coverage across news outlets, at least online. A few pieces are responsible and accurately report our findings. But a number do not, stating instead that the discovery of dinosaurs – which emphatically are not the same thing as marine reptiles like plesiosaurs – can be linked to sightings of the Loch Ness Monster. Nessie, it could be argued, is relevant to our research given that ideas about sea monsters have indeed been instrumental to some ideas on what Nessie was like (some authors regarded Nessie as a sea monster that became trapped in Loch Ness). However, it is fundamentally missing the point to state or imply that we were analysing Loch Ness reports, since we absolutely were not. I remain dismayed that journalists of some outlets see terms like ‘sea monster’ and maintain that it can only be translated to the public by changing it to ‘Loch Ness Monster’. NO. Resist the urge to dumb down. We can make the world a slightly better place by seeking to educate, and doing so doesn’t mean making a thing super-complicated, boring or off-putting.

Here are media articles covering our research, if you’re interested…

Loch Ness monster was mass delusion triggered by discovery of dinosaurs, study suggests, The Telegraph

Sightings of sea monsters by sailors directly influenced by discovery of fossils in 19th century, The London Economic

Nineteenth-Century Fossil Discoveries Influence Sea Serpent Reports, Forbes

Loch Ness monster mystery solved? Study claims ancient dinosaur discovery influenced delusion, Fox News

Study claims ancient dinosaur discovery influenced delusion, news.com.au

Study Theorizes That Ancient Dinosaur Discovery Fueled Loch Ness Sightings, The Epoch Times

So there we have it. This work forms part of a minor ‘scientific cryptozoology’ movement whereby those of us involved aim to critically analyse cryptozoological data in objective fashion. There aren’t many people doing this, but what’s always obvious is that public interest in such projects is high.

Caption: at least some of us have published technical research, in the peer-reviewed literature, where we aim to evaluate and test cryptozoological claims and hypotheses. In 2011, a re-evaluation of the Hagelund ‘baby Cadborosaurus’ showed that it was most like a misidentified pipefish (Woodley et al. 2011). Image: Woodley et al. (2011).

For previous TetZoo articles on sea monsters and related matters (concentrating on those articles that haven’t been destroyed due to formatting issues at ScienceBlogs and SciAm), see…

Up Close and Personal With the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, December 2018

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Refs - -

de Camp, L. S. 1968. Dinosaurs in today's world. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction 34 (3), 68-80.

France, R. L. 2016a. Reinterpreting nineteenth-century accounts of whales battling ‘sea serpents’ as an illation of early entanglement in pre-plastic fishing gear or maritime debris. International Journal of Maritime History 28 686-714.

France, R. 2016b. Historicity of sea turtles misidentified as sea monsters: a case for the early entanglement of marine chelonians in pre-plastic fishing nets and maritime debris. Coriolis: Interdisciplinary Journal of Maritime Studies 6. 1-24.

Galbreath, G. J. 2015. The 1848 ‘enormous serpent’ of the Daedalus identified. Skeptical Inquirer 35 (5), 42-46.

Heuvelmans, B. 1968. In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang, New York.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters. Arcturus, London.

Paxton, C. G. M. 2009. The plural of "anecdote" can be "data": statistical analysis of viewing distances in reports of unidentified giant marine animals 1758-2000. Journal of Zoology 279, 381-387.

Paxton, C., Knatterud, E. & Hedley, S. L. 2004. Cetaceans, sex and sea serpents: an analysis of the Egede accounts of a “most dreadful monster” seen off the coast of Greenland in 1734. Archives of Natural History 32, 1-9.