Oh wow, we’re at Part 6 in the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series already. You’ll need to have seen at least some of the previous articles to make sense of this one: you can either follow the links below, or click through the links in the sidebar. In Part 5 we looked at the first of a series of assumptions made by those who’ve advocated the TMMD contention; namely, that Late Jurassic sauropods had a population structure similar to that of megamammals. In this article, we look at a second assumption…

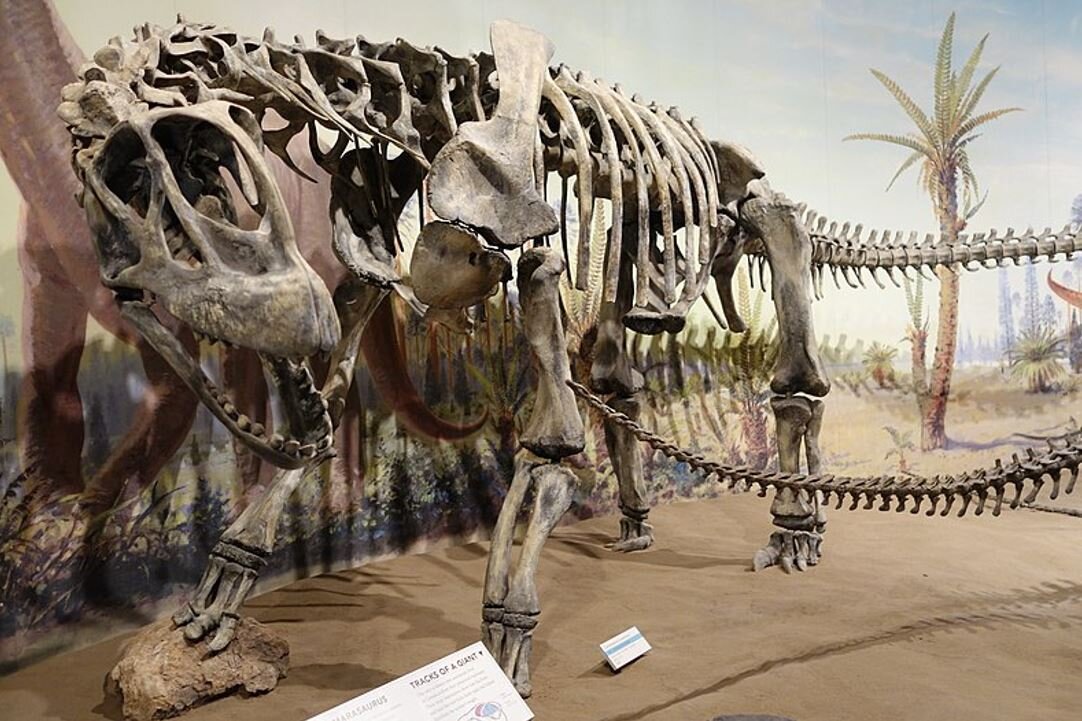

Caption: we know that the Morrison Formation sauropod Camarasaurus ranged from New Mexico in the south to Montana in the north. However, this applies to the whole genus, and no one Camarasaurus species has a range that encompasses this whole region. How widespread were those species when they were alive? Image: Etemenanki3, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Assumption 2: sauropods and other big dinosaurs were similar to Holocene megamammals in ecology and distribution. An assumption inherent to the TMDD position is that big dinosaur species should have had geographic ranges similar to those of Holocene megamammal species. Holocene megamammals often have – or had, prior to human intervention – continent-wide distributions, and exist at low species- and genus-level diversity. Ergo, sauropods and other big dinosaurs should be assumed likewise. A species like, say, Diplodocus carnegii should have a bison-like range that encompasses essentially the whole of North America, and such is its ecological impact across this vast area that the claimed existence of similar species should be viewed with scepticism.

Caption: there’s an assumption that modern faunas - where megaherbivore diversity is low - are representative of the way things ‘should’ be. But prehistoric faunas show that we live in an impoverished world where diversity is lower than the standard for the Cenozoic. Image: (c) Jay Matternes.

Well…. no, perhaps. For starters, the idea that megamammals ‘should’ or ‘must’ exist at low diversity – while true to an extent (there are always going to be less proboscideans that antelopes, less antelopes than rodents) – is skewed by unusual modern conditions. The modern age has a depauperate fauna relative to that of the Pleistocene, Pliocene or Miocene, and the fact that modern Africa is only home to one or two proboscideans doesn’t mean that this is the ‘typical’ condition for the continent. Indeed, you don’t have to look very hard to see Cenozoic mammal faunas where multiple megamammal species – including rhinos and even proboscideans of several lineages – lived contemporaneously (those paying special attention to this series of articles will have seen this issue discussed in the comments already).

Caption: extant megamammals very often have historic ranges that involve the better part of a continent. This map shows the estimated range of the North American bison, though a caveat is that it includes data from a Holocene population sometimes regarded as a distinct, extinct species (Bison occidentalis). Image: Cephas, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

What about the assumption that sauropods and other big dinosaurs should have megamammal-like, continent-wide ranges? For reasons we still don’t fully understand, this seemingly wasn’t the case. In fact big dinosaurs of some or many groups were perhaps less geographically widespread than we might predict based on the ranges occupied by megamammals. Diplodocus carnegii, for example, didn’t range across the entire available landmass of North America*. Rather, we only know of it from Wyoming, Utah and New Mexico (Upchurch et al. 2004, Weishampel et al. 2004). And this wasn’t a one off chosen because D. carnegii is unusual or special: this sort of thing is typical for Mesozoic dinosaurs, and in fact it’s unusual to find evidence pointing to a broad, megamammal-like distribution for a Mesozoic dinosaur genus, let alone a species.

* Sea levels were especially high when it was alive, so continental North America in its modern form wasn’t available to it anyway. UPDATE: be sure to see the comments on this, it’s by no means clear that we have a good handle on the data required to say anything confident about the geographic ranges of Jurassic sauropods. Much work remains to be done.

Caption: large ornithischians during at least part of the Late Cretaceous may have been provincial - that is, endemic to areas smaller than those we might expect based on the ranges of modern megamammals. Note that this diagram is now quite misleading in that the animals shown were not contemporaneous as Lehman (2001) thought, plus some of the locations pinpointed as discovery sites for the respective taxa are erroneous. Image: Lehman (2001).

This is weird. One possibility is that we’ve been duped by an incomplete fossil record, and that the species concerned actually did have megamammal-like distributions, we just don’t know it yet. But it may also be that the relevant dinosaurs were endemic to latitudinal and altitudinal zones smaller than those occupied by megamammals. Lehman (2001) made a strong case for dinosaur provinciality – it’s been called intracontinental faunal endemism – in the Late Cretaceous. He argued that Late Cretaceous ornithischians were limited to regions corresponding to two or three big US states, or one or two Canadian provinces (see also Lehman 1997). Similar arguments for provinciality in Late Cretaceous ornithischians have made more recently by other authors (Sampson et al. 2010, 2013), though it should be noted that some of the ‘provinciality’ reported for the species concerned might be bogus (Fowler 2017). Regardless, my take from the fossil record as a whole is that large dinosaurs of many groups were relatively provincial and did not have megamammal-like ranges. In part, perhaps this is because they seemingly lived in a mosaic or patchwork world where habitats were more complex, more broken up, less monotonous over distance than those which support megamammals today (Whitlock et al. 2018; and see Part 4). Perhaps factors of dinosaur physiology, foraging style, feeding ecology and social behaviour also meant that they were better at living provincial lives than megamammals.

Caption: Sampson et al. (2010) argued that high provinciality was present in the North American ceratopsids of the Campanian, though some of their conclusions have since been challenged. Image: Sampson et al. (2010).

To bring this back to the TMDD contention, it means that a given area – a continent, country, county or other territory – should be expected to have more big-bodied dinosaur taxa than the same area would have Holocene megamammals. In other words, saying “we can’t possibly have 10 sauropods in this area because the same area only supports one Holocene megamammal” is inconsistent with the whole of the Mesozoic fossil record.

I’ve been criticising arguments put forward by Don Prothero (mostly those made in Prothero 2019) in this series of articles. But, somewhat ironically, I think that Don got things right – this being that sauropods and megamammals are not necessarily playing by the same ecological and habitat-use rules – in his 2013 book on indricotheres. When comparing the ecosystems that includes indricotheres with those inhabited by sauropods, he said “Here, the comparison is more problematic, since large sauropods are unlike any large land mammals that has ever lived (in size as well as many anatomical as well as physiological features), and so it is hard to analogize the Late Jurassic forests of the Morrison with the Oligocene scrublands and deserts of central Asia” (Prothero 2013, p. 85). Yup.

Caption: there’s a mostly unspoken assumption in discussing sauropod biology that they were somehow similar to proboscideans. In reality, extinct proboscideans (like the Woolly mammoth shown here) were living in a very different world from modern elephants, likewise for other extinct giant mammals (like Paraceratherium), likewise for sauropods (like the apatosaurine shown here). Image: Darren Naish.

In the next article, we’ll look at a third assumption, and this time it’s the assumption that just won’t die when it comes to Mesozoic ecosystems: namely, the assumption that Mesozoic plants were low in nutritional value, so low that the Mesozoic flora was incapable of supporting the numerous, fast-growing megaherbivores it so obviously did. Come back soon. Oh, and thanks as always to those contributing to the comments section. As you’ll know if you’re a regular, a lot of valuable and interesting additional data and commentary appears in the TetZoo comments. They help keep the blog alive, as they should for any blog.

For the previous article in this series, see…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 1, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 2, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 3, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 4, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 5, April 2020

For previous TetZoo articles on sauropods, brontotheres, giraffes and related issues (linking where possible to wayback machine versions), see…

Giraffes: set for change, January 2006

Biggest…. sauropod…. ever (part…. I), January 2007

Biggest sauropod ever (part…. II), January 2007

The hands of sauropods: horseshoes, spiky columns, stumps and banana shapes, October 2008

Thunder beasts in pictures, March 2009

Thunder beasts of New York, March 2009

Sauropod dinosaurs held their necks in high, raised postures, May 2009

Inside Nature’s Giants part IV: the incredible anatomy of the giraffe, July 2009

Testing the flotation dynamics and swimming abilities of giraffes by way of computational analysis, June 2010

Paul Brinkman’s The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush, March 2011

The sauropod viviparity meme, May 2011

Necks for sex? No thank you, we’re sauropod dinosaurs, May 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part I), December 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part II), January 2012

Greg Paul’s Dinosaurs: A Field Guide, February 2012

Junk in the trunk: why sauropod dinosaurs did not possess trunks (redux, 2012), November 2012

That Brontosaurus Thing, April 2015

Unusual Giraffe Deaths, November 2015

Burning Question for World Giraffe Day: Can They Swim?, June 2016

10 Long, Happy Years of Xenoposeidon, November 2017

The Life Appearance of Sauropod Dinosaurs, January 2019

Refs - -

Lehman, T. M. 1997. Late Campanian dinosaur biogeography in the western interior of North America. In Wolberg, D. L., Stump, E. & Rosenberg, G. D. (eds) Dinofest International: Proceedings of a Symposium Sponsored by Arizona State University. Academy of Natural Sciences (Philadelphia), pp. 223-240.

Lehman, T. M. 2001. Late Cretaceous dinosaur provinciality. In Tanke, D. H. & Carpenter, K. (eds) Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press (Bloomington & Indianapolis), pp. 310-328.

Sampson, S. D., Loewen, M. A., Roberts, E. M. & Getty, M. A. 2013. A new macrovertebrate assemblage from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian) of southern Utah. In Titus, A. L. & Loewen, M. A. (eds) At the Top of the Grand Staircase: the Late Cretaceous of Southern Utah. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana, pp. 599-620.

Upchuch, P., Barrett, P. M. & Dodson, P. 2004. Sauropoda. In Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H. (eds) The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press (Berkeley), pp. 259-322.

Weishampel, D. B., Barrett, P. M., Coria, R. A., Le Loeuff, J., Xu, X., Zhao, X., Sahni, A., Gomani, E. M. P. & Noto, C. R. 2004. Dinosaur distribution. In Weishampel, D. B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H. (eds) The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press (Berkeley), pp. 517-606.

Whitlock, J. A., Trujillo, K. C. & Hanik, G. M. 2018, Assemblage-level structure in Morrison Formation dinosaurs, Western Interior, USA. Geology of the Intermountain West 5, 9-22.