If you were following the hominin-themed discoveries of that long-ago era known as the 1990s, you may well remember the hot news, published in Science in 1994 and 1996, on Homo erectus…

As announced in those papers (Swisher et al. 1994, 1996), these archaic, Asian hominins seemingly had an extremely long tenure in the continent. They were there from a surprisingly early point in hominin evolutionary history and persisted there until extremely recently. That latter fact means that they overlapped in time with modern humans like us and also – far to the west in Iberia – with the last of the Neanderthals. This was (and still is) a big deal because it was one of several discoveries which proved that hominin evolutionary history didn’t follow a ‘one species at a time’ model but instead involved a bush-like pattern of lineages where several species were contemporary.

The main story told in the book I want to discuss today – Garniss Curtis, Carl Swisher and Roger Lewin’s 2000 Java Man: How Two Geologists Changed the Course of Human Evolution* – concerns efforts to pin down the ages of some famous Javan hominid fossils via the application of argon-40/argon-39 dating. These specimens are, most prominently, the Mojokerto child skull, discovered in 1936, and the Sangiran cranium, found the following year. These were conventionally assumed to be somewhere round about 700,000 years ago, and thus from close to the end of the Middle Pleistocene (or Chibanian), but the radiometric dating was shocking: the Mojokerto child proved to be about 1.81 million years old, and the Sangiran specimen 1.66 million years old. That’s close to the end of the Early Pleistocene (or Galesian).

* I’m working from the 2001 UK edition, so am citing it as ‘2001’ throughout.

Caption: Ngandong on the map; it’s in the northern part of East Java, the nearest city being Surabaya to the east. The term ‘Ngandong’ today is synonymous with the archaeological site that yields the H. erectus specimens discussed here. Stegodonts, extinct cattle, rhinos, tapirs and a large tiger (Panthera tigris soloensis) are also known from the site. Image: Google maps.

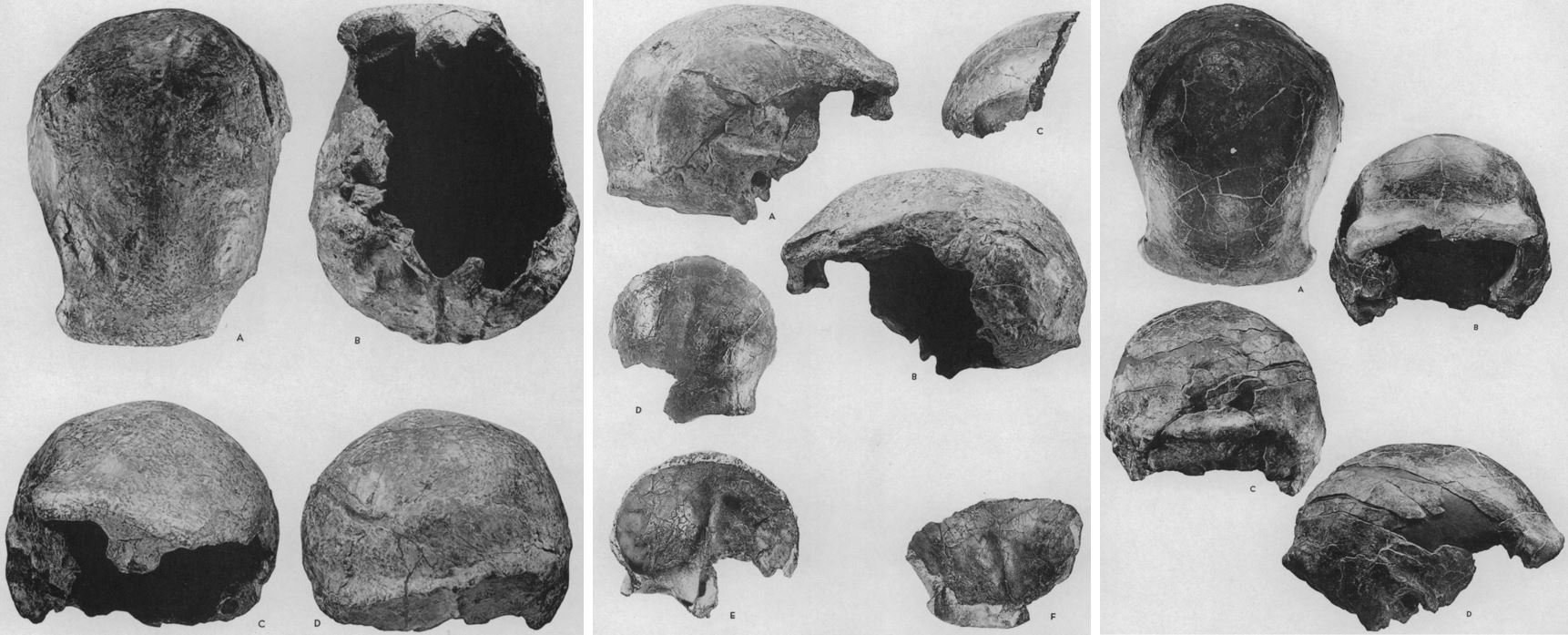

A separate set of fossils – the 12 partial skulls of Ngandong in Java that came to characterise a form of hominin known as Solo man (after the area’s Solo River) – form the focus of the book’s final chapters. The Solo hominin has been regarded as a distinct species (Homo soloensis), as a form of Neanderthal, as part of Homo erectus, and as part of Homo sapiens. Most workers today do regard it as part of Homo erectus. Curtis et al. (2001, pp. 223-229) regarded the fossils as being between 53,000 and 27,000 years old and thus from near the end of the Late Pleistocene, this being the radically surprising result they published in 1996 (Swisher et al. 1996). More recent dating work has pushed the age of the specimens back in time to somewhere around 100,000 years ago (Indriati et al. 2011), which is still Late Pleistocene but puts them tens of thousands of years prior to the time when H. sapiens moved through Asia, or migrated to Australasia.

Caption: a montage of various of the Solo H. erectus fossils, showing skullcaps in various stages of completeness. Those shown here mostly come from adult individuals. By extrapolating complete skull size, we can see that these were large animals, with skulls generally larger than those of H. sapiens. How so many crania came to be preserved in the same area has been the subject of some speculation: was this a product of taphonomy or transport by water, or had these remains been deliberately collected or assembled before discovery? Images: from Weidenreich’s 1951 monograph on Solo man, in public domain.

This book is effectively the backstory to the team’s research on these fossils, and it does a good job of telling the tale engagingly and in a way that connects it with the various debates occurring within palaeoanthropology at the time. The title is a bit superlative and also misleading given that I honestly doubt that the two geologists referred to in the title – Garniss Curtis and Carl Swisher – really did all that much in terms of contributing to the human gene-pool. But you can see what the title is getting at.

One of the reasons that we like reading about palaeoanthropology – part of the reason for it being the perennial subject of a massive number of first-person narratives about work on specific fossils and the controversies surrounding them – is the politics; the internecine turf wars, fall-outs and squabbles; the human drama. I didn’t pull Java Man off the shelf in order to win titillation from my reading of such skirmishes, but the book does deliver on this front, and it’s interesting stuff.

Caption: at left, the Mojokerto child skull photographed at Sangiran Museum, Sragen, Indonesia. At right, Dutch palaeontologist G. H. Ralph von Koenigswald with the skull, other specimens nearby. von Koenigswald is discussed throughout the book and is an important figure in the discovery, history and interpretation of these fossils. Images: Midori, CC BY 3.0 (original here); Tropenmuseum / National Museum of World Culture collection, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

The Mojokerto child incident. The book stats with a cold open whereby Swisher and Curtis are examining the fabled skull of the Mojokerto child while at Gadjah Mada University in Java in the September of 1992. They want to pin down its age using geochronology, but that can only be done if a sample of the adhering matrix is collected. So Swisher opts to use a knife to scrape away a small amount of material. That might not sound like a big deal, but in the world of fossils and other rare objects it's what’s known as destructive analysis. You can’t just do destructive analysis on a whim: you need special permission, something that might involve the consultation of any number of high-ups, and – sometimes – controlled conditions and written agreement. Clear from the text is that the fossil’s caretaker – Indonesian archaeologist Teuku Jacob – was unprepared for and surprised by the application of a tool, and he takes Swisher aside and aims to politely but obliquely explain why his actions were absolutely not acceptable (Curtis et al. 2001, p. 14).

Caption: at left, Garniss Curtis, the geologist who’s essentially the primary character of the book. Curtis died in December 2012; this photo shows him in Wyoming in 2001. At right, a c 1960 photo showing Curtis with (at left) Jack Evernden and a mass spectrometer. Images: Gilbert WG, CC BY 2.5 (original here); J. Hampel / UC Berkeley (taken from this obituary at UC Berkeley News).

There’s the implication from the book’s early chapters that this incident resulted in all sorts of fallout, and I had high hopes for an exciting tale of cross words, banishment from Indonesia for the book’s authors, and even a court case or two. But… no, we don’t really return to this saga and I felt a bit cheated. The book’s implication on Swisher’s actions is that the ends justify the means, since the data that Swisher and colleagues obtained did pin down the Mojokerto child’s age, and ultimately were important in improving our knowledge of Homo erectus’s evolutionary history on the Asian continent. However, Swisher’s actions were wrong and disrespectful and the book certainly doesn’t convey this. It would be a pretty dangerous precedent if people examining fossils – no matter how credentialed and senior those people are – thought it within their rights to remove fragments, no matter how small, for their own pet projects.

On Louis Leakey and Don Johanson. A minor part of the background story to Curtis’s innovations in geochronology concern his disagreements with Louis Leakey. Working with Jack Evernden in 1961, Curtis used potassium/argon dating to establish that Leakey’s famous ‘nutcracker man’ Zinjanthropus (now Paranthropus) boisei was a surprising 1.75 million years old, much older than Leakey thought. However, “Louis repeatedly refused to believe dates that Garniss and Evernden produced for other fossils, when the dates did not jibe with what Louis wanted or believed” (Curtis et al. 2001, p. 19) and they ended up falling out.

Caption: replica of the famous 1959 ‘Zinj’ skull at the Natural History Museum, London. It is today classified as Paranthropus boisei and surely deserves the massive amount of publicity achieved at the time of its publication. The taxonomic history of Australopithecus, Zinjanthropus and Paranthropus is complex. Image: Emőke Dénes, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Another famous palaeoanthropologist – Don Johanson; Curtis et al. (2001, p. 106) quote Tim White’s description of him as “a nail-polish salesman in Yves St. Laurent pants and Gucci sneakers” – is also initially a colleague but later becomes an enemy. Early in the book, Curtis and colleagues have as their academic base the Berkeley Geochronology Center (BGC), which since 1985 was allied with the Institute of Human Origins (IHO). But this was not a happy marriage. The BGC view was that the IHO – and in particular its president, Johanson – were “spending far too much time on public relations activities – such as television appearances and writing popular books – to the detriment of fund-raising for the institution as a whole” (Curtis et al. 2001, p. 110). In turn, the BGC was accused by the IHO as being a bunch of “fucking nerds” (p. 110). There’s then more discussion of belittlement, jealousy, personality clashes, mischaracterisations of the BGC’s work and accomplishments, and descriptions of outbursts (from Johanson) that involved shouting and the throwing of objects.

Things in the book come to a head when, in April 1994, members of the BGC meet up with philanthropist Phyllis Wattis for lunch at the Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse, the aim being to discuss their new Javan discoveries. Johanson, apparently by coincidence, unexpectedly turned up at the same restaurant and gave some hard stares on arriving and leaving. From there, things went rapidly downhill. It turned out that Johanson had been speaking to Wattis with funding in mind, and his interpretation – and that of other people on the IHO board – was that the BGC team were fishing for cash. The Chez Panisse incident, as it became known, then precipitated a series of events that resulted in the IHO tearing itself apart and ejecting the BGC from its premises, locking the BGC out of their lab, and ultimately in a June 1994 court case. My treatment here is a highly condensed summary of a long-running and complex series of events.

Caption: I became curious about the appearance of Chez Panisse and discovered that it has its own Wikipedia page. Apparently, it’s famous in the farm-to-table movement. Images: Calton, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); stu_spivack, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

Multiregionalism and regional continuity. A good section of the book – maybe a third of it – isn’t about the specific specimens that Curtis, Swisher and co worked on, nor about the politics that surrounded the study of these remains, but instead covers ‘big picture’ issues in Asian hominin evolution, and in particular the conflict over the multiregional hypothesis (this is where modern humans are posited as having evolved from a network of interbreeding pre-sapiens populations distributed across the modern range of our species). I admit to feeling some degree of frustration on seeing how much of the book was devoted to this topic. I get this a lot (I mean: frustration while reading books due to the apparent familiarity of the content) and it’s definitely a me problem, not a problem with the book.

Caption: a cast of Sangiran 17 on show at Beijing Museum of Natural History, one of the best Javan H. erectus fossils and a key specimen used in linking the Javan hominins to those of Zhoukoudian in China. Image: Bjoertvedt, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

The bottomline is that the substantial geological age discovered for Javan erectus fossils like the Mojokerto and Sangiran specimens was and is important to the multiregional hypothesis, essentially because it’s at odds with the regional continuity required if erectus fossils in eastern Asia are posited as having evolved into the sapiens of the same area. What of the younger age that Curtis et al. (2001) thought correct for the Solo specimens? They argue that the anatomically archaic nature of these fossils is fully at odds with the idea that these are part of a population that could be considered continuous with H. sapiens. When they were writing, they thought that the Solo specimens were contemporaneous with Asian H. sapiens populations and thus needed to emphasize the anatomical disparity (Curtis et al. 2001, pp. 229-230). The anatomical argument remains valid, of course, but today we’re back to thinking of the Solo people as rather older than Asian (and Australasian) H. sapiens populations in any case (Rizal et al. 2020).

Towards the latter part of the book, Curtis et al. (2001, pp. 185-200) describe how proponents of multiregionalism (Milford Wolpoff in particular) responded to their new data. Primarily, this response was inconsistent and contradictory with previous multiregional arguments; in addition, Curtis et al. (2001) argue throughout that their work is consistent with the Out of Africa, single origin hypothesis for H. sapiens, and at odds with multiregionalism.

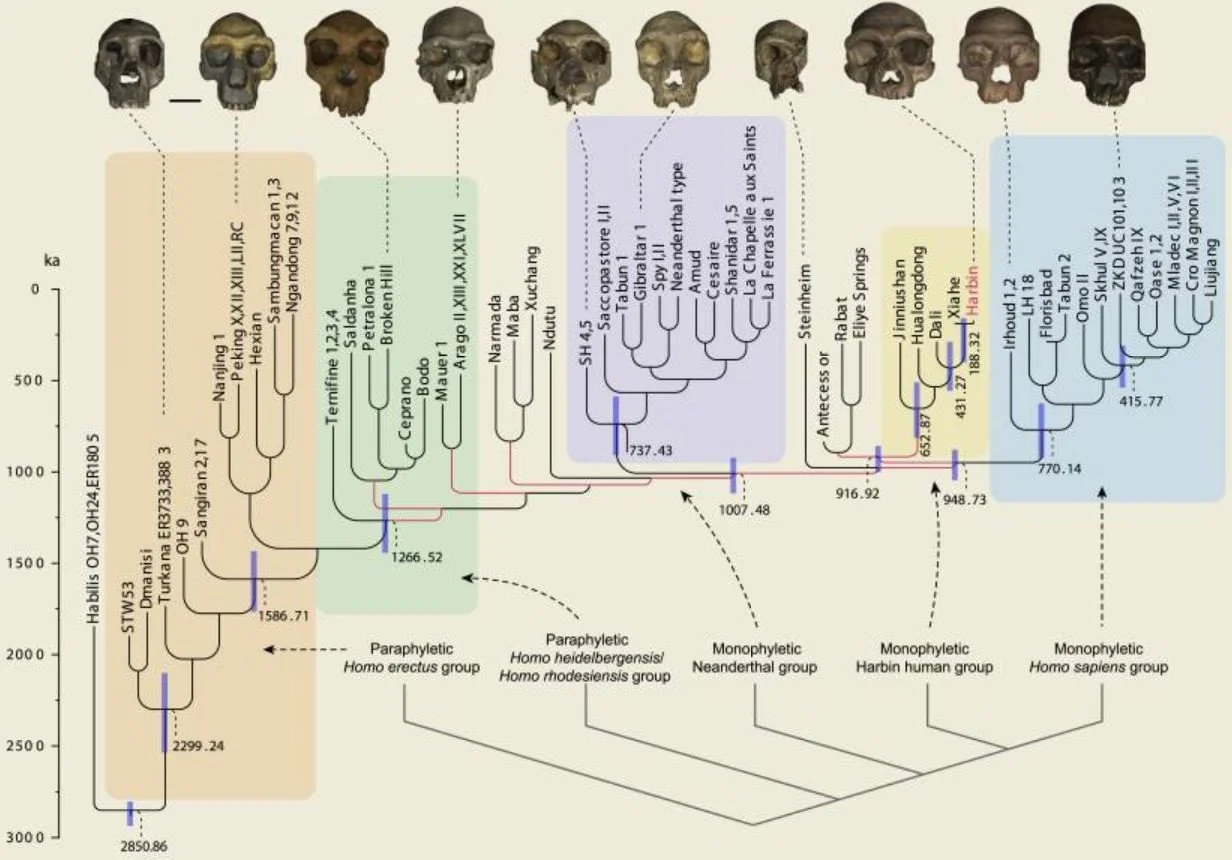

Caption: palaeoanthropologists are famously resistant to the use of computer-assisted phylogenetics… nevertheless, there are at least few published cladograms within the field. This tree (from Ni et al. (2021), on the Harbin hominin lineage) shows how H. erectus is outside the clade that includes heidelbergensis, Neanderthals and moderns. What’s also notable here is that the lineages conventionally included within H. erectus form a paraphyletic group. We can agree that that group is a species if we want (and most researchers do want to maintain that view), but it means that some erectines, if you will, are phylogenetically closer to the heidelbergensis + Neanderthal + modern clade than are others. Image: Ni et al. (2021).

Wrap-up. If you’re interested in the history of studies on Homo erectus in Asia, in the politics and personalities involved in hominin research, and in debates about hominin evolution, taxonomy and phylogeny, I recommend this book and really enjoyed reading it. It is, however, concerned almost entirely with specific discussions and discoveries pertaining to a particular set of Javan fossils, so shouldn’t be imagined as covering the whole history of Homo erectus in Java, in east Asia more broadly, and certainly not in Eurasia in entirety. How does Curtis et al. (2001) complement other popular books devoted to Homo erectus? I’ll come back to that at some point in the near future.

Caption: there are a massive number of hominin-themed books. Here are just a few. Image: Darren Naish.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on hominins and other hominids, see…

Zihlman’s ‘pygmy chimpanzee hypothesis’, October 2012

Why Humans Are Important to Studies of Primate Diversity, July 2014

The Cautious Climber Hypothesis, March 2019

Piltdown Man and the Dualist Contention, March 2023

Refs - -

Curtis, G., Swisher, C. & Lewin, R. 2001. Java Man: How Two Geologists Changed the History of Human Evolution. Little, Brown and Company, London.

Rizal, Y., Westaway, K. E., Zaim, Y., van den Bergh, G. D., Bettis, E. A., Morwood, M. J., Huffman, O. F., Grün, R. Joannes-Boyau, R., Bailey, R. M., Sidarto, Westaway, M. C., Kurniawan, I., Moore, M. W., Storey, M., Aziz, F., Suminto, Zhao, J.-x., Aswan, Sipola, M. E., Larick, R., Zonneveld, J.-P., Scott, R., Putt, S. & Ciochon, R. L. 2020. Last appearance of Homo erectus at Ngandong, Java, 117,000–108,000 years ago. Nature 577, 381-385.

Swisher, C. C., Curtis, G. H., Jacob, T., Getty, A. G., Suprijo, A. & Widiasmoro. 1994. Age of the earliest known hominids in Java, Indonesia. Science 263, 1118-1121.

Swisher, C. C., Rink, W. J., Antón, S. C., Schwarcz, H. P., Curtis, G. H. & Widiasmoro, A. S. 1996. Latest Homo erectus of Java: potential contemporaneity with Homo sapiens in Southeast Asia. Science 274, 1870-1874.