Chickens are remarkable animals, and I’ve written about them a few times at TetZoo before, albeit always too briefly (see links below). I really need to write about them at length at some point; I actually worked for a few years as a specialist chicken researcher and gathered a lot of interesting information on these birds. Anyway… here, I want to talk about one chicken in particular: a famous individual that has been mentioned several times in the recent literature (e.g., Kaiser 2007). Namely: Aldrovandi’s monstrous rooster.

Caption: original image of Aldrovandi’s monstrous rooster, from volume 2 of his Ornithologia. Credit: scan archived by University of Oregon (original here).

Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605) was an Italian philosopher, physician and naturalist who’s most frequently mentioned for his three-volume Ornithologia of 1600. Therein, he wrote a lot about chickens, and part of his text covers mutants and monsters, predominantly conjoined chickens and chickens with extra limbs. My Latin is not that hot (err… Caecilius est pater), so it’s fortunate that Fernando Civardi transcribed, and Elio Corti translated, the chicken section of this work such that it’s today available to English readers. The resulting volume, published in 2009, is titled The Chicken of Ulisse Aldrovandi (Corti & Civardi 2009). It’s a great read if you like chickens.

For completeness I should note that Aldrovandi’s chicken text was actually translated beforehand (in 1963) by another worker (L. R. Lind) (Aldrovandi 1963). This version is said to be plagued with translation errors (hey, not my opinion) and hence is not preferred by specialists.

Caption: the cover of Lind’s 1963 translation of Aldrovandi’s chicken text. What’s that thing on the cover? Well… that’s a whole ‘nother story. Credit: amazon.

To return to the monstrous rooster, the book includes a fine depiction of it as well as a good paragraph of description and interpretation. Aldrovandi himself observed this remarkable bird, alive, in the collection of Francesco Medici – the Grand Duke of Tuscany – and described it as so shocking in appearance that “it struck fear into brave men with its terrifying aspect”. It was blackish overall with white bases to its feathers, and its feathers are said to have looked scale-like. Given that clean-edged, metallic feathers in many gallinaceous birds can look superficially scale-like (one of the best examples being the feathering of male Green peacock Pavo muticus, sometimes called the dragonbird), this is perhaps not as surprising as it might sound.

Caption: there are a great many amazing gallinaceous birds, and here’s one of my favourites: the Green peacock. This is a captive individual at Tierpark Berlin. There’s an entire TetZoo article on this species: see links below. Credit: Markus Bühler, used with permission .

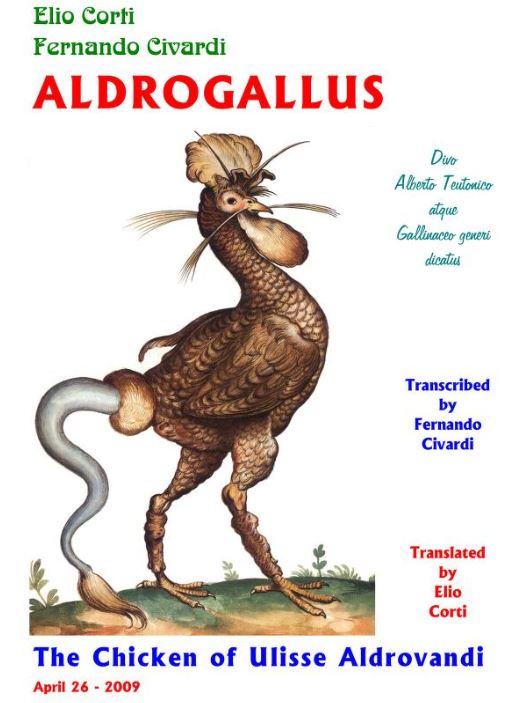

The monstrous rooster did not possess a conventional fleshy comb and paired wattles but had feathers in their place: a large feathery crest projected from the top of the head and two spines – interpreted by Aldrovandi as feather quills lacking barbs – pointed upwards and outwards from the forehead, “as if they were two horns”. Tufts of long, bristle-like structures emerged from either side of the bill (close to the nostrils) and from the back of the neck as well. The legs were feathered down to the ankles and the feet appear not to have been remarkable. The bird appears to have been tall and large, based on the illustration (though no scale was provided). A colourised interpretation of the animal was produced by Corti & Civardi (2009).

Caption: cover of Corti & Civardi (2009), showing a colourised version of Aldrovandi’s monstrous rooster. Oh to see such a bird in life. Credit: Corti & Civardi (2009).

Finally, the most remarkable feature was the tail. It emerged from a whitish, rounded mass of feathers, and was long, slender, fleshy and pale blue. A mass of feathers formed a tuft (Aldrovandi called it a “flock”) at the tip. This tail reminded Aldrovandi of that of “quadrupeds”, predumably meaning lizards or mammals like rats or cats. Here I would remind you that a maniraptoran with a long tail ‘should not’ – so we think based on fossils – have a tail superficially recalling that of a lizard, but instead have a resplendently feathered one. The weirdness here perhaps indicates that the embryological development of this animal’s tail was likely different from that of extinct long-tailed birds and other Mesozoic maniraptorans.

Indeed, this bird sounds so weird overall that I sometimes even wonder whether it really was a domestic chicken, and not a member of some other (presumably now extinct) gallinaceous bird. But I don’t think that this is really up there as a possibility: it really was a member of Gallus gallus.

So… wow. What are we to make of all this?

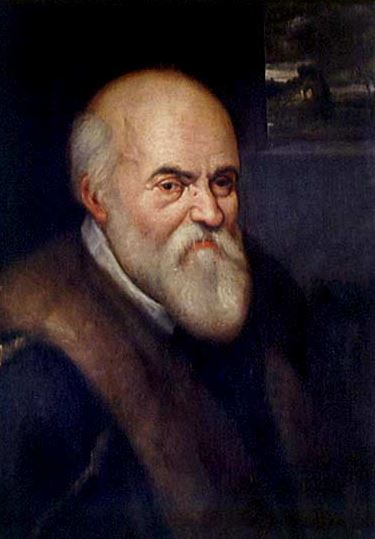

Caption: Agostino Carracci’s portrait of Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), physician, philosopher and naturalist. Credit: image in public domain, from wikipedia (original here).

For starters, what do we know about Aldrovandi? Well, quite a lot. He was a credible, well trained individual who had studied law, philosophy, mathematics and logic at university; he published on insects and other invertebrates and was even credited by Linnaeus as the ‘father of natural history’. He also wrote extensively about anomalous cases in zoology and medicine and collected enough of them that they were (posthumously) published in the 1640 volume Historiae Serpentum et Draconum and the 1642 Monstrorum Historia. His serpents and dragons book also includes a brief discussion of the monstrous rooster, but doesn’t add information relative to that included in his Ornithologia.

Caption: damn, chickens are awesome. These birds belonged to a group living semi-wild on Madeira. Credit: Darren Naish.

What we can glean from Aldrovandi’s writings is that he lived within the ethnographic landscape of Renaissance Italy, by which I mean that he seemingly believed in things (like human-like monsters and mythical beasts of far-off lands) that we today know not to exist. But his writings on direct, specific cases show that he was not credulous or prone to endorsing half-truths. He was critical of stories about basilisks, for example (thought at the time to result from the production or brooding of eggs by roosters)*. Furthermore, his illustrations of known animals are often highly accurate, as you can see from the examples shared here. Indeed, his writings on other anomalous specimens – like the ‘Homuncio’ (a short-statured Indian man whose body was draped with massive fleshy growths) – have been interpreted as biologically accurate (Ruggieri & Polizzi 2003).

* For those curious, I’m not exploring the basilisk angle here; I have to avoid it for now. Constraints of time.

Caption: Aldrovandi was a skilled and accurate artist, and his illustrations of known species - familiar and foreign - are usually highly accurate, as is demonstrated by these chickens. His chicken text also includes several illustrations of curassows, and they’re all essentially accurate. Credit: Corti & Civardi (2009).

The major caveat here is that Aldrovandi’s text and illustration of the monstrous rooster were (so far as we can tell) produced some considerable time after his observation of the bird, in which case all sorts of discrepancies might have crept in. The possibility that it had been modified or fitted with an artificial tail is not out of the question, but can’t be tested and is just an idea I need to mention in passing. We do know of other cases whereby animals have been made to look remarkable to impress or dupe observers, after all.

But, all in all, I’m inclined to think that the case was genuine, and that a long-tailed mutant rooster really was observed at some point in the 1500s by an erudite young man.

Caption: if a ‘dino-chicken’ ever does come to pass, it should be awesome and beautiful — like a real chicken. Err, in which case I don’t think anyone will look at it and think of a connection with the Mesozoic maniraptorans it’s meant to evoke. Whatever. Credit: Rebecca Groom.

I will leave you with one final thought. Jack Horner’s ‘dino-chicken’ project seeks to create a mutant fowl with a long, bony tail and other ‘ancestral’ features, all brought into existence via genetic and embryological modification. And research underpinning such efforts has already been published (Rashid et al. 2018). Was Aldrovandi’s rooster a demonstration that some of these developmental changes can occur without modern, deliberate modification? In other words, could it have been a real, ‘natural’ dino-chicken; one that existed four-hundred years before our time? If only the body, or skeleton, of this amazing bird had been preserved.

For other TetZoo articles linked to things mentioned here, see… (note: TetZoo ver 2 articles - the ScienceBlogs ones - are now appearing without their images, yay!)…

How to prevent cannibalism in pheasants, March 2010

The snood of the turkey, the wires and rackets of the motmot, the face of the rook, February 2011

Chickens, 2012, April 2012

Turkeys vs peafowl, the great debate, January 2013

The other turkey, January 2013

The other peacock, January 2013

Refs - -

Corti, E. & Civardi, F. 2009. The Chicken of Ulisse Aldrovandi. www.summagallicana.it

Kaiser, G. 2007. The Inner Bird: Anatomy and Evolution. University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Ruggieri, M. & Polizzi, A. 2003. From Aldrovandi’s “Homuncio” (1592) to Buffon’s girl (1749) and the “Wart Man” of Tilesius (1793): antique illustrations of mosaicism in neurofibromatosis? Journal of Medical Genetics 40, 227-232.