Long-time readers of Tet Zoo with exceptionally good memories might recall me describing my first encounter with live – albeit captive – fossas…

Caption: my local zoo (Marwell Wildlife, Hampshire, UK) has had fossa on display several times and I was just blown away when I first found this out. I observed this male (photographed in 2015) scent-marking objects in his enclosure. Note how muscular the forelimbs are. Images: Darren Naish.

The Fossa Cryptoprocta ferox is an endemic Madagascan carnivoran, notable for its superficially cat-like form, large size (head and body = to 80 cm, tail = to 70 cm) and proportionally long tail. It forages on the ground and is a swift runner and bounder, but it’s also an excellent climber, able to scale vertical trunks as well as run along horizontal branches and boughs.

Caption: these photos (again from Marwell Wildlife) aren’t the best, but they at least show that fossas are proficient at climbing and walking on branches and such. The especially bad photo at right is from 2006, the very first time I ever saw a fossa (a Tet Zoo ver 1 article celebrating that event is here). Images: Darren Naish.

Fossas are widespread across Madagascar and potentially findable anywhere there except for the central highlands. They are, however, in decline and now restricted to peripheral forests, mostly dry deciduous ones. Habitat loss and fragmentation is a concern, as is persecution due to perceived predation on chickens, hunting for the pot – something that apparently occurs at high rates in some places (Hunter & Barrett 2011) – and, additionally, the possibility of disease transmission from domestic dogs and cats. The wild population is optimistically estimated at somewhere around 2500 individuals.

Fossas are opportunistic predators, capable of predating on just about all of Madagascar’s endemic animals, perhaps including the Indi Indri indri, the largest extant lemur. There are claims of them killing bushpigs and even cows (Nowak 1999); direct evidence for the consumption of bushpigs is on record but might be the result of scavenging rather than predation (Rasoloarison et al. 1995). There are also concerns in some places that they might be dangerous to people, though such claims are generally thought to represent superstitious fear more than any real danger. They’re predominantly solitary but there are reports of co-operative hunting where – respectively – pairs, mothers and their youngsters, and three adult males have been seen hunting together (Garbutt 1999, Lührs & Dammhahn 2010, Hunter & Barrett 2011). The suggestion has been made that co-operative hunting was more useful, and hence perhaps more frequent, in prehistoric times, back when an assortment of larger prey species was available (Lührs & Dammhahn 2010). Juvenile fossas are relatively slow-growing and not independent until about 12 months old.

Caption: yawning captive fossa at left, unfortunately not showing the teeth especially well. The view of the whiskers is good though. The fossa gets appropriate coverage in The Velvet Claw – a BBC Natural History Unit TV show that I’ve discussed here many times now – and the series even features an animated view of its skull and tooth anatomy. Images: Darren Naish; BBC Natural History Unit.

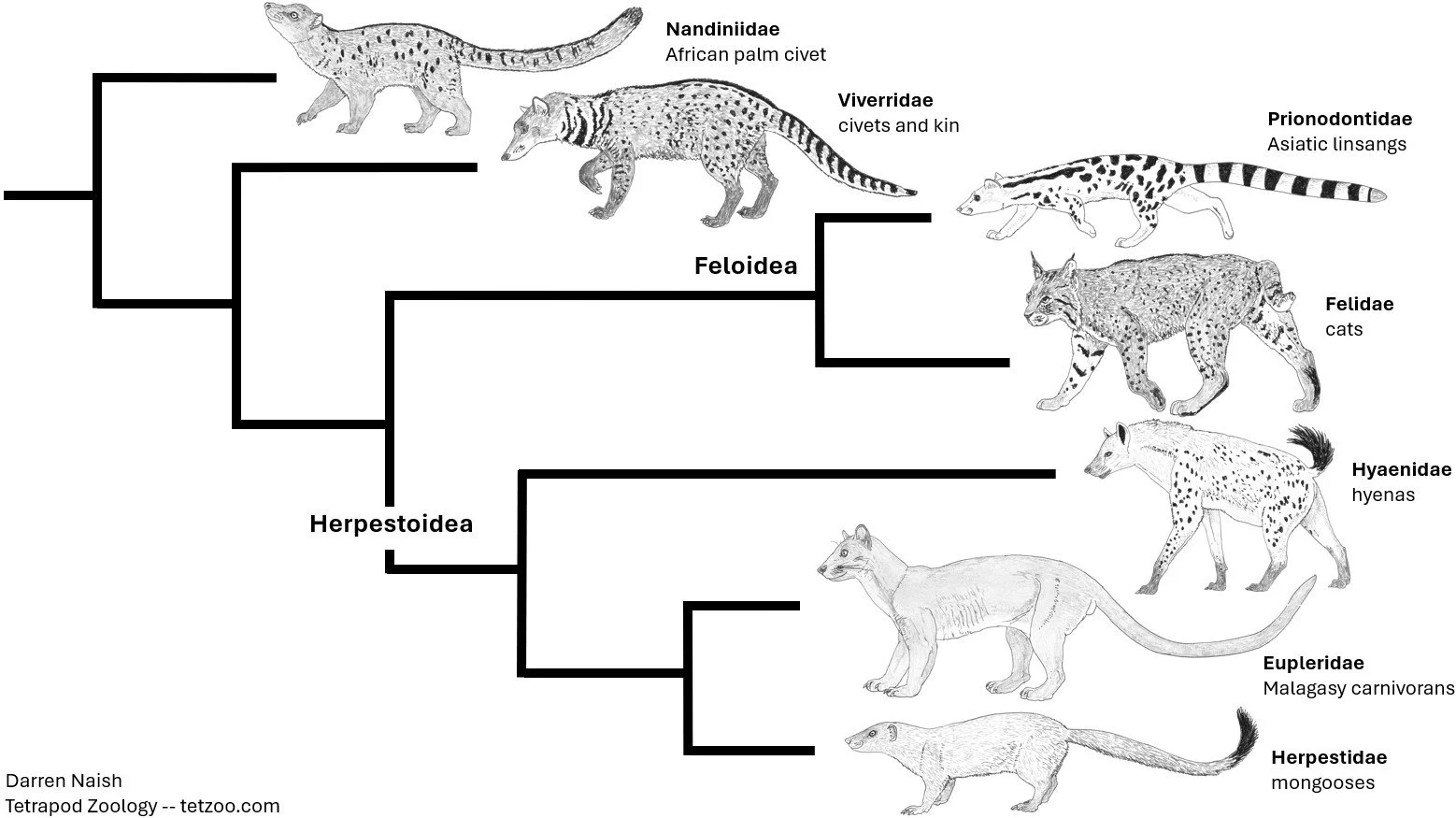

On phylogeny and that name. Fossas and two other endemic Madagascan carnivores (the Falanouc Eupleres goudotii and Fanaloka Fossa fossana) were regarded as aberrant viverrids (representing the subfamilies Euplerinae and Cryptoproctinae) until relatively recently (e.g., Garbutt 1999). Seen as such, they were thought to represent an invasion of Madagascar independent from that involving the galidiines, a second group of endemic carnivorans conventionally regarded as mongooses. Genetics has shown that euplerines, cryptoproctines and galidiines are neither viverrids nor mongooses, but are close kin within a clade (Eupleridae) that’s close to mongooses (Agnarsson et al. 2009, Hassanin et al. 2021).

Caption: simplified cladogram of Feliformia, the ‘cat branch’ of Carnivora. This topology is based on that of Agnarsson et al. (2009) but putting Asiatic linsangs with cats comes from Gaubert & Veron (2003). What phylogeny indicates is that feliforms should basically be imagined as ‘civet-type carnivorans’, with cats and hyenas being stand-out deviations from the baseline ecomorph. The images used here are all from my in-prep textbook project, which can be supported via my patreon. Image: Darren Naish.

The name ‘fossa’, incidentally, has several different pronunciations. Some authors spell it ‘fosa’. Like most English speakers who’ve learnt words from books (rather than from hearing them spoken), I’ve generally assumed that it’s pronounced how it’s spelt: foss-a. So my world was rocked a few decades back when I learnt that the ‘real’ pronunciation is something like “fooosh, with a semi-silent ‘a’ at the end” (I forget now where I first read this but might have learnt it from author and zoologist Chris Lavers). I used this pronunciation for a while. Partly thanks to the 2005 DreamWorks movie Madagascar, there’s also the idea that the word should be pronounced with a long ‘o’, such that it’s ‘fooo-sa’. But these days I feel that we’ve gone full circle, and that even those people who know everything I’ve just summarised above go with the ‘foss-a’ pronunciation I described initially.

The ’Cave fossa’. Here’s where things take a different turn. Ever since 1902, we’ve known of a larger, extinct fossa, named Cryptoprocta spelea by French zoologist and geographer Guillaume Grandidier (1873-1957). Grandidier actually regarded it as a variant of the living species, and it was only ‘up-ranked’ to species status in 1935.

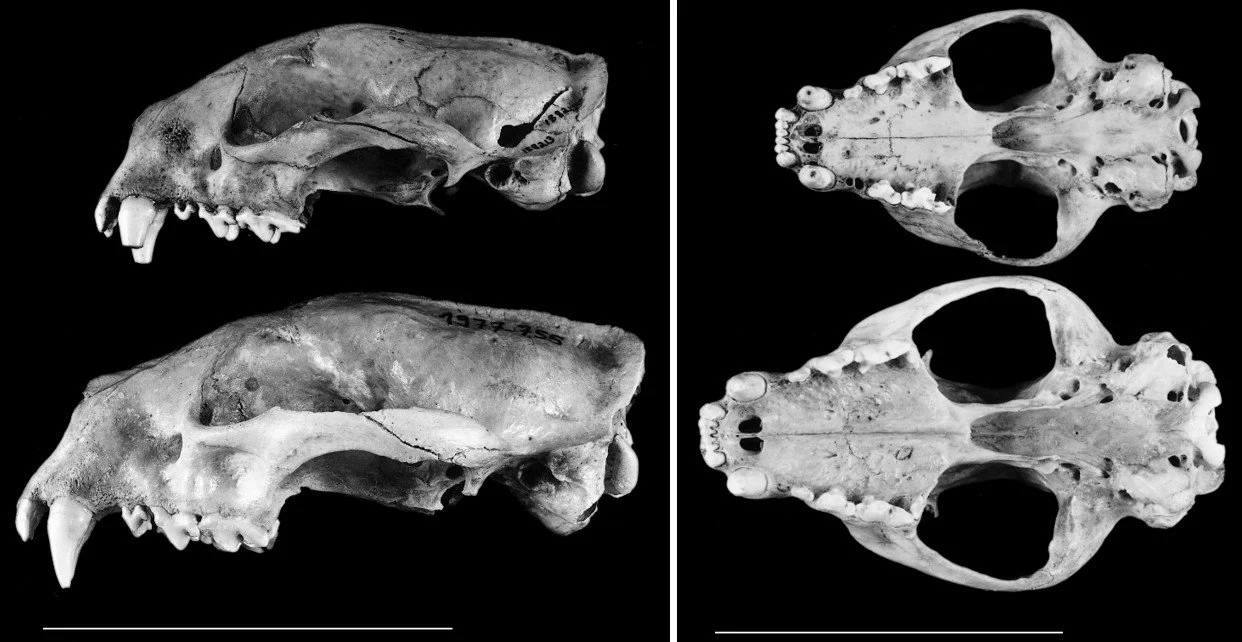

Caption: these photos (from Goodman et al. 2004) show how the skull of C. spelea is substantially larger and bigger-toothed than that of C. ferox. Differences also suggest that the two might have looked more obviously different than we usually imagine: C. spelea has, for example, a straighter zygomatic arch, proportionally longer muzzle and might have had a more upturned nose (based on the form of the nasal bones). Images: Goodman et al. (2004).

Very little is known about this animal, other than that it was larger than the extant species (perhaps being twice as large; Burness et al. (2001) estimated it at 17 kg, compared to 8.6 kg for big males of the extant species). It’s assumed, in the absence of better data, that C. spelea was similar in ecology, behaviour and appearance to C. ferox. Fossils referred to C. spelea are known from right across Madagascar and imply that it was a generalist, able to make a living in diverse habitats (Goodman et al. 2004).

Caption: a montage of Madagascan cryptids (several others exist, of course). At left, the Vorompatra, generally thought to represent recollections of aepyornithids. At upper right, the Antamba, generally associated with the cave fossa. At lower right, a superficially ape-like rendition of Tratratratra, a creature usually linked with various of the recently extinct large lemurs. Images: Pagodroma721, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here); Daniel Burch Caballé, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Philippe Coudray (from here).

A Mad ‘black panther’. If you’ve ever heard anything about C. spelea, the odds are high that you’ve also heard the idea that it might not be a prehistoric animal but one that persisted to modern times. A few radiocarbon dates have been obtained for its remains, these variously suggesting ages of 3000-1700 years before present (Crowley 2010). Similar things have been said about several other elements of the prehistoric Malagasy megafauna – endemic hippos, giant lemurs and elephant birds among them – and there’s been some effort to link local words to various of these animals and to collect possible eyewitness accounts (e.g., Burney & Ramilisonina 1999). Said accounts are predominantly of the ‘my grandfather told me that his grandfather saw this when he was a boy’-type, though there are exceptions. A fossa said to weigh 30 kg was reported by a forestry ranger in 1954, for example (Goodman et al. 2004, p. 141). And then we come to Ben Freed’s account.

Freed is an assistant professor at Eastern Kentucky University, USA, whose published research involves lemur ecology and behaviour, conservation, anthropology and the history of extinctions in Madagascar. While conducting field research in Ampamelonabe in Montagne d’Ambre National Park (in the far north of Madagascar) in 1989, Freed had the most extraordinary and exciting encounter. This was reported in a 2021 technical paper (Nomenjanahary et al. 2021), and I here quote the relevant section in full…

In December 1989, at Ampamelonabe main camp, I awoke at about 0600h to a strange noise coming from the supply tent that was 6 meters away. All tents were on wooden platforms. I descended slowly from my tent to see a long black tail extending from the supply tent, while a clanging and pushing sound came from inside the tent. The animal had partially destroyed it. As I took a step closer to the tent, the animal turned around, first bumping its head against the tent fly, and then it repositioned itself with its head looking directly at me, staring out from the tent entrance.

It looked like a fosa. But this was no reddish-brown Cryptoprocta ferox; I had seen plenty of those in daylight at the site. Its head was solid black, as were its body and tail. Its head, body, and tail were much larger than those of C. ferox. The head was big, and the animal didn’t have the rounded ears that characterize C. ferox. I estimated its body mass at maybe 20-25 kg. Only a few seconds later, it ran off very fast away from me.

My initial reaction was disbelief. After a few seconds, I tried to follow the animal, but it was already long gone. What had I seen? The size and color just were so different from C. ferox. It was SO big, and it was very black. No C. ferox ever looked like that.

Its head and body (without the tail) must have been over one meter in length. The tent’s floor length was 152 cm, and given its position in the tent when it bumped its head against the fly, I could estimate its length from the tip of its nose to the base of tail at between 102-115 cm. Plus, it had a very long tail, just as does C. ferox (almost as long as its head and body).

At that time, in 1989, I knew nothing about Cryptoprocta spelea, a relative of C. ferox believed to be long extinct. I was perplexed by what I had seen. I packed up my backpack and headed to Joffreville. On the way, I was convinced that I had seen one of two things. My first explanation was that I had seen a black panther. But a large felid of this sort had never been reported on the island! As I started doubting that possibility, and while attempting to describe it to the forestry agents at the park barrier, I remembered my guide’s description of TWO different kinds of fosa in the forest. I asked him about their coat colors. One was reddish-brown, he said, and it preyed on lemurs or crested ibis. This was clearly C. ferox. The other one was much larger, black, and it could take down cattle. To confirm, I asked him if this second one was ‘noir.’ Yes, he stated, but he also said that he had never personally seen it. So I was inclined to dismiss the idea that there were indeed two species of Cryptoprocta in the forest, and embrace the notion that someone had introduced a large black felid to Madagascar.

After that morning, however, I realized that the second was the better of my two explanations. What I had seen matched my guide’s description of the larger fosa. I could not imagine this black fosa preying on lemurs; it was so much longer, bigger, and stronger than C. ferox. I didn’t think about the fact that, in the late Holocene, there were also much bigger lemurs living in the forest. I also did not recall that large predators that lose their habitual prey will turn to smaller prey species to survive.

When later I visited the World Wildlife Fund technical consultant in Diego, he asked why I hadn’t photographed the animal. Honestly, the camera was in the supply tent which the fosa had severely damaged.

When in 1992 I told my dissertation advisor about this incident, he suggested that maybe it was a melanistic form of something. But it was so much bigger than C. ferox. I had previously been within 0.5 meters of a C. ferox on a couple of occasions, so I knew its size.

In 2004, after Goodman et al. (2004) published their article on the specific identification of subfossil Cryptoprocta, one of my fellow former graduate students sent me a copy of that article and suggested that maybe C. spelea was what I had seen. But most of my colleagues remained skeptical. After all, everybody knew that Cryptoprocta spelea was long extinct.

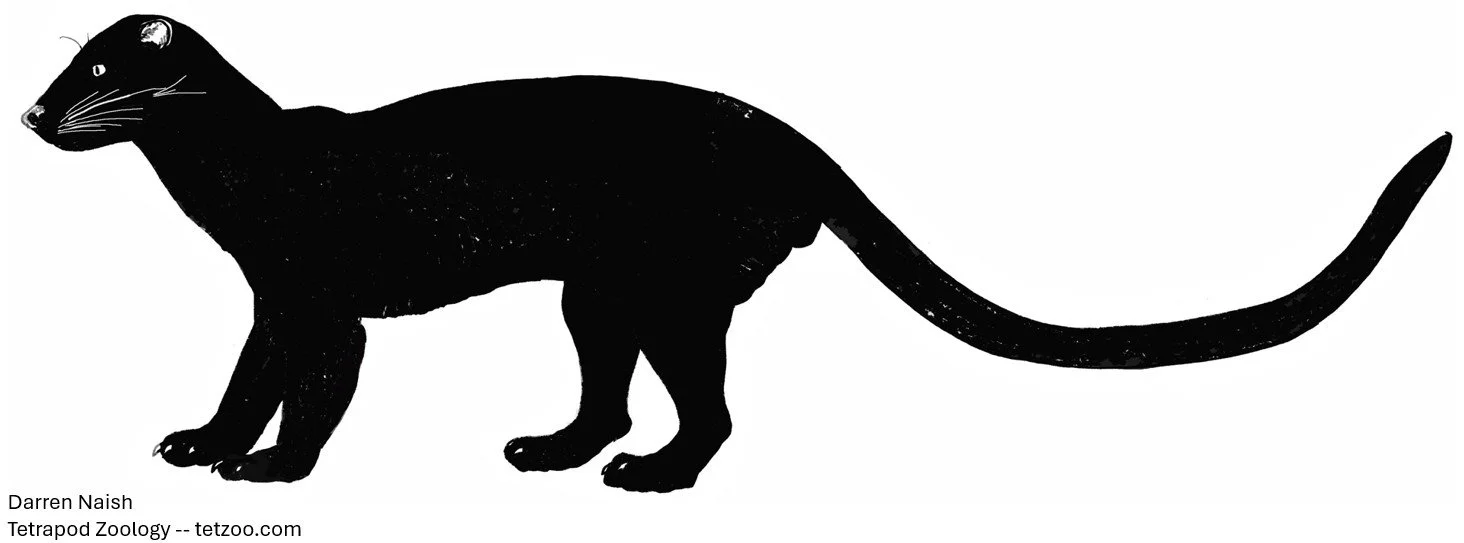

This is such a great, and clear, account that it’s difficult to explain away (I really wish someone would create an artistic depiction of Freed’s observation…. hint hint). I mean… this just has to be a valid encounter with a giant, black fossa, and a fossa anatomically quite different from C. ferox. Inspired, Freed, Eva Stela Nomenjanahary and colleagues interviewed local people in the Montagne d’Ambre area and (among 90 interviews) collected 42 cases where people shared knowledge of a big, predatory mammal that sounded like a giant fossa (Nomenjanahary et al. 2021). These big fossas were much darker than C. ferox, some being described as dark red but others as greyish, blackish or wholly black. The oldest accounts dated to 1980 and the most recent to 2020 (Nomenjanahary et al. 2021). The animals were often said to be similar in size to, or larger than, male dogs, and were also regarded by witnesses as potentially dangerous, and as showing no fear of dogs.

Caption: a speculative reconstruction of a giant black fossa, an obvious difference from C. ferox being the size and shape of its ears. Image: Darren Naish.

I was struck by Freed’s concern that he might have seen a black panther (meaning, surely, a melanistic leopard Panthera pardus). Over the years, claims have been made that Madagascar might be home to cats of diverse sort. In Mystery Cats of the World (first published 1989 and released in much updated form in 2020), Karl Shuker drew attention to Paul Cazard’s 1939 mention of stories about “giant lions” from various caves on the island, this being linked to suggestions that Madagascar might be home to large cats (Shuker 2020). Could these be opaque references to especially big fossas?

The fitoaty. It's become well known in recent years that Madagascar is home to a wholly black, gracile cat that appears to be a recently evolved form of feral domestic cat Felis catus. Associated with the forests of the Masoala Peninsula in the north-east, it’s known as the fitoaty and it remains to be determined whether it represents a population of ancient or modern origin (Borgerson 2013, Farris et al. 2016). Given the fact that the term ‘fossa/fosa’ is used across Madagascar for carnivorans other than Cryptoprocta, the possibility exists that ‘fossa sightings’ – sometimes concerning ‘black fossas’ – might sometimes refer to black cats of this sort, not black euplerids.

Caption: at left, a topographical depiction of Madagascar emphasizing the location of the Masoala Peninsula in the north-east. Never forget, incidentally, how large Madagascar is: at around 590,000 km sq it’s similar in area to Texas, and thus bigger than Spain, Germany or Thailand. At right, a fitoaty photographed by camera trap, from Farris et al. (2016). Images: Sisyphos23, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Farris et al. (2016).

But that’s not the case with Freed’s 1989 animal, nor the other Montagne d’Ambre animals, which were as big as or bigger than dogs, noting as having much shorter forelimbs than hindlimbs, and were not identified as being cat-like (Nomenjanahary et al. 2021). In other words… I think we can eliminate the idea that the giant black fossas being discussed here are anything to do with cats of any sort.

The idea that C. spelea, or an animal very much like it, might persist into modern times seems radical, and arguably unlikely. But maybe Madagascar – parts of it, anyway – is the sort of place where such animals might persist, or… might have persisted until recently. Any animal of this sort must – if still alive – be critically endangered given the state of things. Should we be looking for cryptic giant fossas in Madagascar’s north? Might investigation – perhaps involving eDNA or camera traps – take things further? Stay tuned, more news is coming…

Caption: speculative depiction of giant black fossa (based on Freed’s 1989 encounter) compared to C. ferox. Scale bar = 1 m. Image: Darren Naish.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on carnivorans, often of cryptozoologically relevant sort, see…

Suburban Camera Trapping, Week 1, May 2025

Otaria, the Southern Sea Lion, May 2025

Legend of the Black Dog, August 2022

Meeting the Hayling Island Jungle cat, March 2022

The Incredible South American Maned Wolf, March 2022

Conservation Concerns for South America's Remarkable Endemic Dogs, Revisited for 2022, January 2022

Ross Barnett’s 2019 The Missing Lynx: the Past and Future of Britain’s Lost Mammals, May 2021

Refs - -

Agnarsson, I., Kuntner, M. & May-Collado, L. J. 2009. Dogs, cats, and kin: a molecular species-level phylogeny of Carnivora. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 54, 726-745.

Borgerson C. 2013. The fitoaty: an unidentified carnivoran species from the Masoala peninsula of Madagascar. Madagascar Conservation & Development 8, 81-85.

Burness, G. P., Diamond, J. & Flannery, T. 2001. Dinosaurs, dragons, and dwarfs: the evolution of maximal body size. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 14518-14523.

Burney, D. A. & Ramilisonina 1999. The kilopilopitsofy, kidoky, and bokyboky: accounts of strange animals from Belo-sur-mer, Madagascar, and the megafaunal "extinction window". American Anthropologist 100, 957-966.

Crowley, B. E. 2010. A refined chronology of prehistoric Madagascar and the demise of the megafauna. Quaternary Science Reviews 29, 2591-2603.

Farris, Z. J., Boone, H. M., Karpanty, S., Murphy, A., Ratelolahy, F., Andrianjakarivelo, V. & Kelly, M. J. 2016. Feral cats and the fitoaty: first population assessment of the black forest cat in Madagascar’s rainforests. Journal of Mammology 97, 518-525.

Garbutt, N. 1999. Mammals of Madagascar. Pica Press, Mountfield.

Gaubert, P. & Veron, G. 2003. Exhaustive sample set among Viverridae reveals the sister-group of felids: the linsangs as a case of extreme morphological convergence within Feliformia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B 270, 2523-2530.

Goodman, S. M., Rasoloarison, R. M. & Ganzhorn, J. U. 2004. On the specific identification of subfossil Cryptoprocta (Mammalia, Carnivora) from Madagascar. Zoosystema 26, 129-143.

Hunter, L. & Barrett, P. 2011. Carnivores of the World. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Lührs, M.-L. & Dammhahn, M. 2010. An unusual case of cooperative hunting in a solitary carnivore. Journal of Ethology 28, 379-383.

Nomenjanahary, E. S., Freed, B. Z., Dollar, L. J., Randrianasy, J. & Godfrey, L. R. 2021. The stories people tell, and how they can contribute to our understanding of megafaunal decline and extinction in Madagascar. Malagasy Nature 15, 159-179.

Nowak, R. M. 1999. Walker’s Mammals of the World, Sixth Edition (two volumes). The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London.

Rasoloarison, R. M., Rasolonandrasana, B. P. N., Ganzhorn, J. U. & Goodman, S. M. 1995. Predation on vertebrates in the Kirindy Forest, western Madagascar. Ecotropica 1, 59-65.

Shuker, K. P. N. 2020. Mystery Cats of the Word Revisited. Anomalist Books, San Antonio, Charlottesville.