As a regular reader of Tetrapod Zoology, you will know I’m sure that I made some effort in 2024 to rescue ruined squamate-themed articles from vers 2 and 3 of the blog…

Caption: I photograph all the slow-worms I see, and here are a few encountered here in southern England during the 2010s and 20s. The deceased individual at left, found in a churchyard while I was on a bat survey, was a big, robust male, and when complete would have been quite large. How large? I can’t reliably say seeing as its posterior half was missing. Images: Darren Naish.

For 2025, events have not allowed much progress, and I’m way behind on my plans, as I am at all times. Here’s your regular reminder that you can help me spend more time generating content for the blog by supporting me at patreon. But today I want to rescue another old squamate-themed Tet Zoo article, this time on one of my favourite animals: Anguis fragilis. The article first appeared here in 2007 and has been updated where appropriate.

The slow-worms. I’ve returned several times on Tetrapod Zoology to the European common slow-worm Anguis fragilis, a legless anguid lizard traditionally thought (read on!) to occur across Europe and Asia as far east as western Siberia. I find slow-worms very charismatic animals. Part of the appeal might be that they are easy to find in the places where I’ve lived; part of it might be that we Brits have such a poor reptile fauna that we hold those few species we do have in special regard; and part of it might be that they’re really cute and cool to look at.

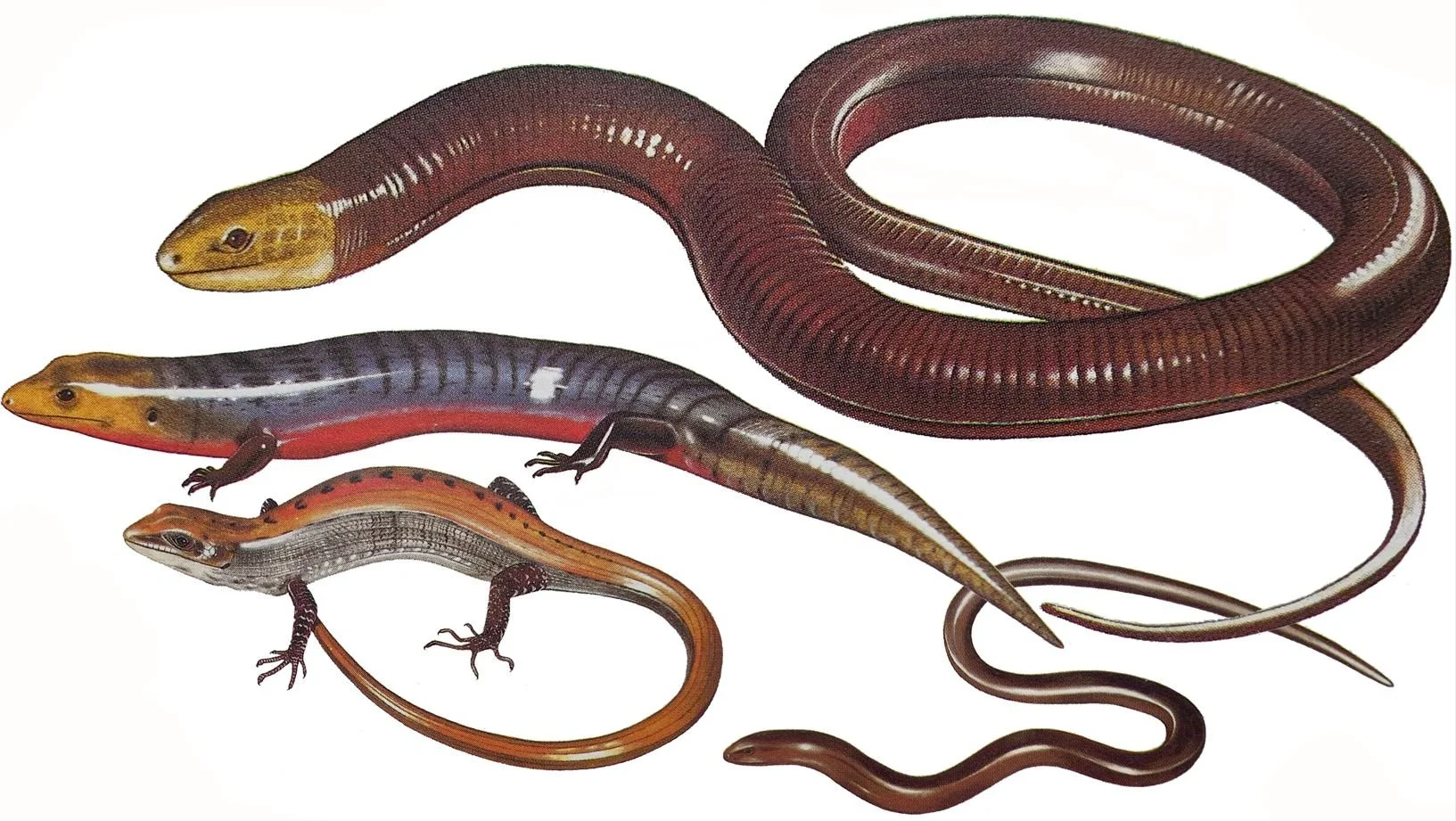

Caption: slow-worms are part of the anguimorph lizard group Anguidae, and indeed are the ‘type’ genus for this group. Here’s a montage of extant anguids, using the brilliant 1983 paintings of Alan Male (I’ve used this same montage in previous Tet Zoo anguid articles). The animals shown here are Sheltopusik Pseudopus apodus (at top), then the brightly coloured galliwasp Diploglossus, the alligator lizard Gerrhonotus at lower left, and Anguis itself at lower right. Images: Alan Male, from Whitfield (1983).

Slow-worms, and their close relatives within Anguidae, are relatively intelligent by lizard standards and captive individuals exhibit behaviours suggesting that they learn to recognise their keepers. They’re long-lived: a captive slow-worm at Copenhagen lived for 54 years. Until recently, experts recognised just two slow-worm species: A. fragilis and A. cephallonica of the Peloponnese and Ionian islands.

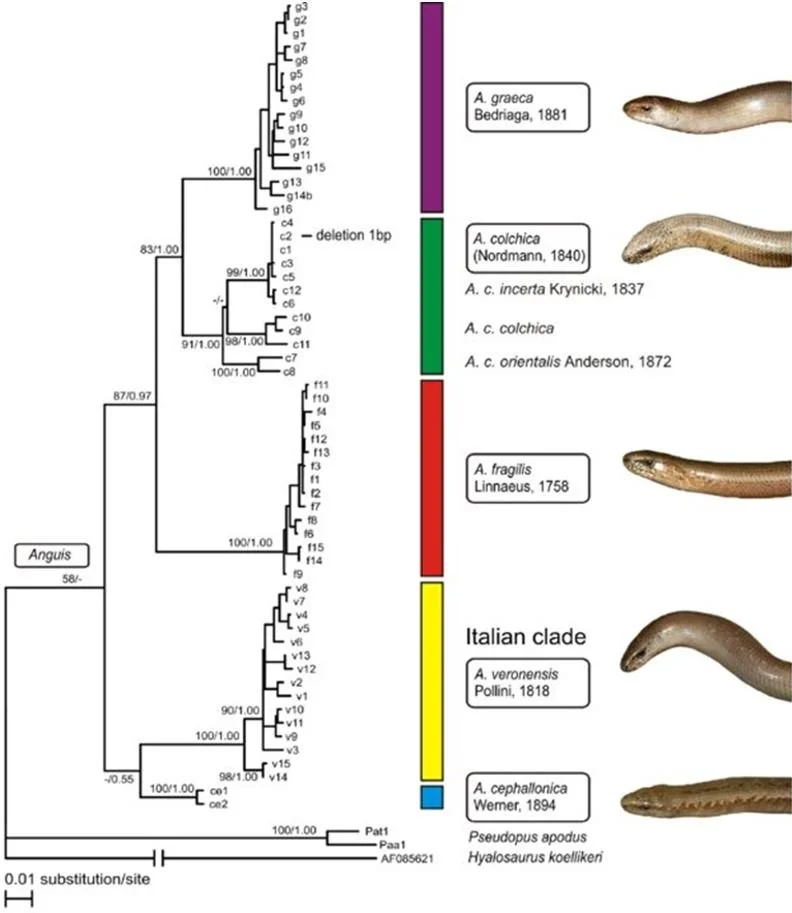

However, 21st century molecular studies have led to the recognition of divergences within this group that occurred way back… as in, during the Miocene (so, around 25 million years ago or more). Lineages that old, in tetrapods, are surely separate species, and these discoveries are mostly responsible for the view that multiple species are present, hence the recent recognition of the Eastern slow-worm A. colchica of Russia and Georgia, Greek slow-worm A. graeca and Italian slow-worm A. veronensis (Gvoždík et al. 2010, 2013). Thus, we now have five extant slow-worm species. Populations from the more eastern part of slow-worm range are relatively understudied, so it’s possible that east Eurasian animals currently labelled as A. fragilis might turn out to be something else, but let’s just see.

Caption: slow-worm phylogeny, from Gvoždík et al. (2013), showing the revised taxonomy they suggest based on this phylogenetic structure. Peloponnese and Italian slow-worms form a clade that’s the sister-group to the remaining taxa. The divergences between the main lineages here appear to have occurred 25 million years ago or more. Image: Gvoždík et al. (2013).

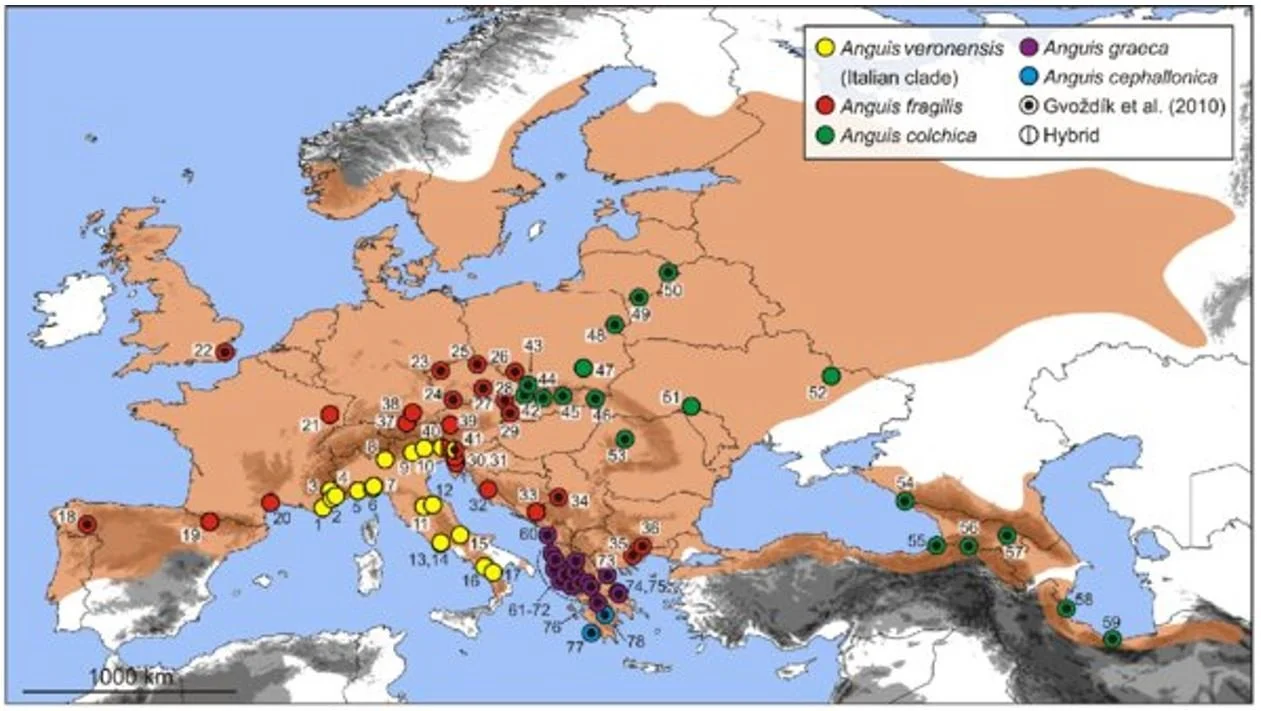

Caption: map showing the geographic origins of the slow-worms analysed by Gvoždík et al. (2013) for their phylogenetic study. The assumption until recently was that slow-worms from throughout the range of these animals (the brown area) belong to Anguis fragilis, but there’s now doubt about this: A. fragilis is widespread in the west, but what about all unsampled regions from the east? The Scandinavian animals should be A. fragilis, and some authors have shown all the animals in the east to be A. colchica (Speybroeck et al. 2016), albeit sharing a fuzzy boundary (running north-south through Poland, and also through Czechia, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) with A. fragilis. Ireland is shown here as devoid of slow-worms but we now know that that’s not right: they’re present, and seem to owe their presence to introduction by people. Image: Gvoždík et al. (2013).

An aside worth mentioning here is that these multiple species are very hard (albeit not impossible, based on scale counts and so on) to distinguish morphologically, and you basically need to know their geographic origins in order to work out which species they might be (e.g., Renet et al. 2018). Some people think that this is fine and that morphology isn’t destiny (especially so in a cryptozoic group of lizards where olfaction is more important than what you look like).

And some other people think that we’ve gone too far in splitting lineages like this and that we don’t need to be giving different species names to each new genetic lineage we document. This is, as you likely know, one of the biggest areas of dispute within 21st century biology and is usually framed as a debate about taxonomy. It’s not about taxonomy (the naming of things) alone though, since it also concerns how we interpret phylogeny, and how we interpret molecular data.

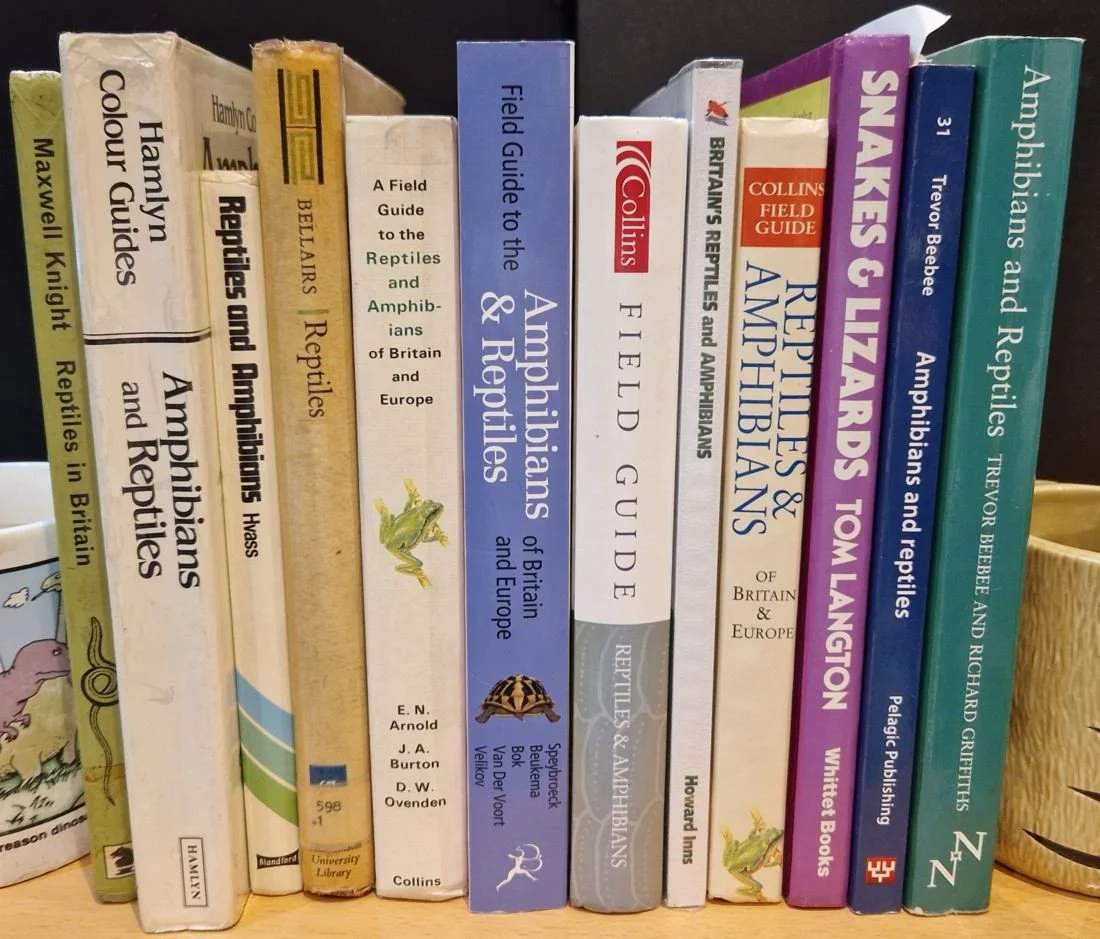

Another aside: as is so often the case with vernacular names, there’s considerable ambiguity on how the common name of this group of lizards should be written. Is it ‘slow worm’, ‘slow-worm’ or ‘slowworm’? Given that these animals aren’t, actually, worms, my thinking is that ‘slow worm’ is wrong. Of the other two options, I dislike both; the hyphen is ugly, but so is the ‘double w’ in ‘slowworm’. Herpetologists who’ve written about these animals have preferred ‘slow worm’ (e.g., Arnold et al. 1978, Inns 2009, Speybroeck et al. 2016) or ‘slow-worm’ (e.g., Knight 1965, Laňka & Vít 1986, Langton 1989, Beebee & Griffiths 2000, Beebee 2013), with the latter winning out by number (I’ve only seen one published use of ‘slowworm’: Hvass 1972). For that reason, slow-worm is the term I’m using here (and will do so in future, when I remember).

Caption: many parts of the world are home to reptile species that are but covered perhaps once, maybe twice, in the literature. Western Europe’s reptile species have been written about on numerous occasions; here are a selection of books that cover slow-worms, albeit often relatively fleetingly. Image: Darren Naish.

Some slow-worms are big. One thing that I find particularly interesting about slow-worms is the question of how big they get. I find this subject interesting because – of all the slow-worms I’ve seen (and I’m now talking only of A. fragilis) – none have ever been longer than 25 cm. Other British people with experience of A. fragilis talk of individuals of 25-30 cm as exceptionally big, so I’m not alone. Despite this, some slow-worms well exceed these lengths: most texts on these lizards list the world record as a male 48.9 cm, discovered in Portsmouth, southern England (Fairfax 1965) but it now seems that the true record-holders are from continental Europe. In 2012, Wolfgang Böhme reported a monstrous German specimen 57.5 cm long (Böhme 2012), but even this was exceeded by a Croatian giant 60.7 cm long (Zadravec & Golub 2018).

Particularly big slow-worms have been reported from Flat Holm and Steep Holm, two small islands in the Bristol Channel. In 1975, British herpetologist Tony Phelps discovered a Steep Holm slow-worm that was 45 cm long, estimated by him to be between 60 and 70 years old. In 1984, an individual 39 cm long was photographed on Steep Holm by slow-worm expert Nick Smith but, because it had a regenerated tail, its original length (i.e., with its intact original tail) would have been about 53 cm.

Caption: it might be obvious how Steep Holm got its name. Muntjac deer used to live on it (maybe they still do) and some died by falling off the sides. I’ve never visited, but I’ve viewed it from afar on several occasions. This photo was taken from Weston-super-Mare in August 2020. Image: Darren Naish.

Back when the biggest slow-worms on record were English, it seemed that an ‘island effect’ was at play in the development of large individuals (Portsmouth is technically an island, albeit one only weakly differentiated from the English mainland). But now that we have very large individuals from widely separated places in continental Europe, it seems that these animals have the potential to become large wherever they occur.

Giant slow-worms are Sheltopusik-like. As documented more than once at his blog – Bestiarium – my friend Markus Bühler discovered a particularly big male slow-worm in Germany. It was dead, perhaps as a result of ingesting poisoned prey, and measured 48 cm.

Caption: extremely large, and sadly deceased, male slow-worm found in Germany by Markus Bühler in 2006. This specimen was preserved and properly measured, and found to be 48 cm in total length. Unlike snakes, legless anguids have long tails: with a bit of imagination you can work out where the body-tail junction is, and note how slender the tail is relative to the thicker part of the body. Image: Markus Bühler, used with permission.

What’s weird is that some of these especially big slow-worms look quite different from the smaller animals I’m used to. Superficially, what with their bulkier proportions and more clearly demarcated scales*, they look rather more like the European glass lizard or Sheltopusik Pseudopus apodus than do typical British slow-worms. The Sheltopusik sometimes gets described as looking like a particularly big slow-worm, the biggest individuals reaching 1.4 m. It occurs in shrubland and steppe habitats in south-east Europe, part of the Middle East and western Asia as far east as Kazakhstan. In the past, it was often included in Ophisaurus, a genus whose numerous species occur across Asia as well as North America (though… there are competing views on the taxonomy of these animals. I’ll come back to this matter in time).

* Slow-worms and glass lizards don’t just possess scales: they’re encased in subrectangular osteoderms. These are highly distinctive as fossils and help explain why the group has such a good fossil record.

Caption: the Sheltopusik does look somewhat like a gigantic slow-worm, but it has a pluck and charm all its own too. Their eyes in particular are striking and make them look very different from snakes (something we’ve discussed here at Tet Zoo before). A consequence of large size is that the skin has more of a ‘plated’ look than it does in slow-worms, the osteoderms appearing more defined and obvious. These photos were taken in Corfu. Images: Markus Bühler, used with permission.

What makes the similarity between big slow-worms and the Sheltopusik especially interesting – in my mind – is that some phylogenetic studies find the Sheltopusik to be the sister-taxon to Anguis (Macey et al. 1999). This makes me wonder if (a) slow-worms (maybe of all species) have the potential to become big and gnarly in appearance like the Sheltopusik, but that this opportunity ordinarily doesn’t allow, or (b) that the relatively small, relatively smooth-scaled and dainty slow-worms of places like the UK represent an unusual, presumably geologically young, clade, with the big, Sheltopusik-like ones being more typical, or phylogenetically ‘basal’, within the slow-worm clade. But that can’t be right in view of the slow-worm phylogeny shown above, where small, dainty British slow-worms are not obviously geologically younger or ‘more derived’ (whatever that means these days…) than other Anguis lineages.

I’ll finish by saying that we still know surprisingly little about slow-worms, despite their familiarity in a scientifically well-studied region. Questions remain about their diet and ecology (they seem to have a tight association with ants. Are they predators of ants or their larvae, or is something else going on here?), and what, exactly, is going on with their distribution (they seem widely distributed in suburban and urban environments across their range – are they good at dispersing? If so, how?).

Caption: I had the impression that slow-worms have been covered on an unusually high number of occasions here, but it turns out that I’ve only written about them three times or so. Given that Tet Zoo is approaching its 20th year of operation, it shouldn’t be surprising that certain familiar species have been covered more than once. These two articles are from ver 1 (2006) and 2 (2007), respectively.

We will return to them in time, I’m sure. Plus, I still have a great many other anguid lizards to write about. My thanks to Markus Bühler and Tobias Möser for their kind assistance with this article.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on squamates, see…

In Quest of Anguids, May 2006

Pompey and Steepo, the World-Record-Holding Champion Slow-Worms, May 2007

Cambodia: now with dibamids!, May 2011

The Tet Zoo Guide to Mastigures, August 2018

The Remarkable Basilisks, May 2023

Do Lizards Really Have ‘Mite Pockets’?, March 2024

Meeting Lake Zacapu’s Garter Snake, March 2024

Ray Hoser, Number 1 Taxonomic Vandal, May 2024

The Mysterious Dibamids, May 2024

The Rehabilitation of Günther’s Black Cameroonian Snake, May 2024

Ikaheka and Other ‘Palatine Draggers’, Cryptozoic Elapid Snakes of Melanesia, June 2024

Arboreal Alligator Lizards of Mesoamerica... and Beyond!, July 2024

Grayiids: Africa Has Water Snakes Too, July 2024

Smaug, Ouroborus, Flat Lizards and More, August 2024

Leiosaurid Lizards: South America, Land of Iguanians, November 2024

What's With All These New Chameleon Names? Chameleons, Part 1, November 2024

Racerunner Lizards of the World Unite, New for 2025!, April 2025

Refs – -

Arnold, E. N. A., Burton, J. A. & Ovenden, D. W. 1992. Reptiles and Amphibians of Britain and Europe. Collins, London.

Beebee, T. J. C. 2013. Amphibians and Reptiles. Pelagic Publishing, Exeter.

Beebee, T. & Griffiths, R. 2000. Amphibians and Reptiles. HarperCollins, London.

Böhme, W. 2012. A record-sized specimen of the western slow worm (Anguis fragilis). Zeitschrift für Feldherpetologie 19, 117-118.

Fairfax, R. A. 1965. Very large English slow-worm. British Journal of Herpetology 2, 229.

Gvoždík, V., Benkovský, N., Crottini, A., Bellati, A., Moravec, J. Romano, A., Sacchi, R. & Jandzik, D. 2013. An ancient lineage of slow worms, genus Anguis (Squamata: Anguidae), survived in the Italian Peninsula. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69, 1077-1092.

Gvoždík, V., Jandzik, D., Lymberakis, P., Jablonski, D. & Moravec, J. 2010. Slow worm, Anguis fragilis (Reptilia: Anguidae) as a species complex: genetic structure reveals deep divergences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55, 460-472.

Hvass, H. 1972. Reptiles and Amphibians in Colour. Blandford Press, London.

Inns, H. 2009. Britain’s Reptiles and Amphibians. WILDGuides Ltd, Old Basing, Hampshire.

Knight, M. 1965. Reptiles in Britain. Brockhampton Press, Leicester.

Langton, T. 1989. Snakes & Lizards. Whittet Books, London.

Laňka, V. & Vít, Z. 1986. Amphibians and Reptiles. Hamlyn, Twickenham.

Macey, J. R., Schulte, J. A., Larson, A., Tuniyev, B. S., Orlov, N. & Papenfuss, T. J. 1999. Molecular phylogenetics, tRNA evolution and historical biogeography in anguid lizards and related taxonomic families. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 12, 250-272.

Renet, J., Lucente, D., Delaugerre, M., Gerriet, O., Grégory, D., Abbat-Tista, C. & Cimmaruta, R. 2018. Discovery of an Italian slow worm (Anguis veronensis Pollini, 1818) population on a Western Mediterranean Island confirmed by genetic analysis. Acta Herpetologica 13, 165-169.

Speybroeck, J., Beukema, W., Bok, B. & Van Der Voort, J. 2016. Field Guide to the Amphibians & Reptiles of Britain and Europe. Bloomsbury, London.

Whitfield, P. 1983. Reptiles and Amphibians: An Authoritative and Illustrated Guide. Longman Group Ltd, Harlow, UK.

Zadravec, M. & Golub, A. 2018. Longer than the longest - two record-breaking specimens of Anguis fragilis from north-western Croatia. Zeitschrift Für Feldherpetologie 25, 105-107.