For reasons, I still have no time at all for blogging, alas. And thus I once again give you an article from the archives. This time, one of my favourite BAT articles. I’ve covered bats a fair bit at TetZoo (see below for links), but this remains one of the most memorable (it has received some minor updates relative to its initial outing, which occurred here in 2006 at ver 1)…

Caption: there aren’t many good photos of Greater noctules (or, at least, available ones online), but this is one of the best. It’s from Popa-Lisseanu et al. (2007) and is used here via CC BY 2.5.

It’s moderately well known among people familiar with bats that the members of several groups – most famously the megadermatids, aka the false vampires or yellow-winged bats – predate on birds. Here, we’re going to look at the bird predation recently documented in another bat group, the vespertilionids or vesper bats. To those of us living in the Northern Hemisphere, vesper bats are the commonest and most familiar of bats, and because they’re generally small, inoffensive, insectivorous bats, the idea that some of them might be bird predators may seem pretty radical.

Noctules (Nyctalus) are a group of Eurasian vesper bats closely related to little yellow bats (Rhogeesa), big-eared brown bats (Histiotus) and little brown bats (Myotis) (Jones et al. 2002). Between six and eight species are currently recognized, with views differing among specialists (Nowak 1999). Noctules are mostly forest-dwelling bats and are large (body lengths 50-100 mm, forearm lengths 40-70 mm) compared to pipistrelles and other typical vesper bats. They have sleek fur that ranges in colour from golden to dark brown. Some species are migratory and make journeys of over 2300 km. They eat relatively large prey, being particularly fond of beetles, and Nowak (1999) mentions a remarkable case where a Eurasian noctule (N. noctula) was observed to catch and eat mice. The species we’re interested in here, the Greater noctule N. lasiopterus, is mostly western European but also occurs as far east as the Urals, and as far south as Libya and Morocco. It isn’t well known, and is also rare.

Caption: an old illustration depicting noctules (albeit not Greater noctules) from one of E. O. Schmidt’s works. Image in public domain.

To better understand the ecology and behaviour of this species, Ibáñez et al. (2001) netted individuals and recorded their wing morphology, and also recorded echolocation calls from the field. Greater noctule wing morphology indicates fast flight in open areas, as they have high wing loading and high aspect ratios. This is quite different from what’s seen in megadermatids and other groups known to be vertebrate predators. These bats are mostly ground- and foliage-gleaning that often hunt from perches. They have low wing loadings and low aspect ratios and use slow, manoeuvrable flight as they glean for mostly terrestrial prey in cluttered habitats.

The echolocation calls of the Greater noctule are long in terms of pulse duration with a low frequency and narrow bandwidth. They are therefore suited for long-range target detection in open air. This technique is quite different from that usually employed by vesper bats, this being suited for short-range prey that are detected in cluttered habitats.

Caption: substantially simplified vesper bat cladogram, as compiled for my vesper bat series of 2011 (see below for links).

Both wing morphology and echolocation style therefore indicate that Greater noctules chase and catch flying prey in the open. But what are they chasing and catching? Ibáñez et al. (2001) found that feathers made up a significant component of the bat’s droppings during March-May and again during August-November. These are the parts of the year when migrating birds pass through their Spanish study area. Both the proportion of feathers in the droppings, and the proportion of captured Greater noctules that produced feather-filled droppings, showed that Greater noctules must capture and eat large numbers of migrating passerines. Bird predation was first documented in this species by Dondini & Vergari (2000), and judging from later comments in the literature it doesn’t seem that they got the credit they deserve for this discovery.

Caption: an imaginative depiction showing a noctule pursuing a robin with predatory intent. Image: Darren Naish.

In contrast to those of bird-eating megadermatids (see this ver 1 article from 2006), Greater noctule roosts are never littered with bird remains (which partly explains why this behaviour was overlooked for so long). Ibáñez et al. (2001) did find fresh, recently cut passerine wings (of a Robin Erithacus rubecula and Wood warbler Phylloscopus sibilatrix) underneath the bats they were netting, and they also found Robin feathers adhering to the claws of one of the captured bats. It seems that Greater noctules catch, overpower and eat the passerines during flight, just as other vesper bats do with flying insects. Greater noctules are clearly large enough and powerful enough to do this: they weigh in at about 50 g and have a wingspan of 45 cm (making them the largest of Europe’s bats). For comparison, a European robin weighs c 20 g (though this goes down to c 15 g after migration) and has a wingspan of 20-22 cm.

Caption: I might not have any photos of noctules catching robins, but I do at least have a lot of photos of European robins. Here are specimens photographed in southern England (left) and Wales. Images: Darren Naish.

Unsurprisingly, this idea has been regarded as controversial and doubtful by some. Bontadina & Arlettaz (2003) argued that the passerine-catching idea was so unlikely that it couldn’t be regarded as correct (excellent use of logic there). They also noted that other noctule species prey on insects and not birds, and that, suspiciously, Greater noctule droppings lack bird bone fragments. None of these arguments count for much. Bird bone fragments in fact are present in Greater noctule droppings, as was reported by Dondini & Vergari (2000), who even subjected the bone fragments to SEM observation to determine conclusively their avian origin (strangely, Ibáñez et al. (2001) did not report the discovery of bone fragments, and Bontadina & Arlettaz (2003) didn’t cite Dondini & Vergari’s (2000) discovery of them). The fact that other noctules don’t hunt passerines means nothing.

Anyway, how did Bontadina & Arlettaz (2003) account for the presence of all those feathers in the Greater noctule droppings? They proposed that the bats regularly eat falling feathers, mistaking them for flying insects! That’s pretty incredible, and arguably more amazing than the idea of predation on passerines. Two responses to Bontadina & Arlettaz’s article were published (Ibáñez et al. 2003, Dondini & Vergari 2004), and both showed that the scepticism was unfounded. The case for passerine predation in Greater noctules is pretty compelling. Note to wildlife camera-people reading this: someone should try and film this behaviour, though for obvious reasons no-one’s even observed it yet (to my knowledge).

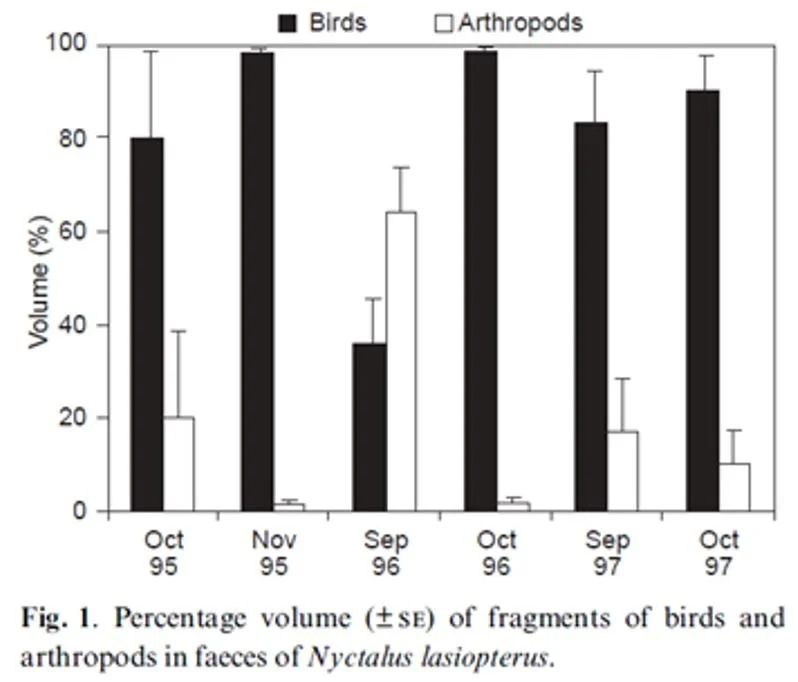

Caption: graph from Dondini & Vergari (2004) with self-explanatory caption.

So Greater noctules are specialist predators that exploit nocturnally migrating passerines, and to date they are the only animals known to do so. There are diurnal raptors (notably Eleonora’s falcon Falco eleonorae and Sooty falcons F. concolor) that specialize on migrating passerines, but nothing else that makes a point of catching those passerines that migrate at night. Dondini & Vergari’s paper ‘Carnivory in the greater noctule bat (Nyctalus lasiopterus) in Italy’ and Ibáñez et al.’s paper ‘Bat predation on nocturnally migrating birds’ therefore have to be two of the most remarkable recent publications in the annals of bat science, and this is a field where lactation in males (Francis et al. 1994), ultraviolet vision (Winter et al. 2003) and the re-evolution of running (Riskin & Hermanson 2005) have recently been reported [UPDATE: remember that the text you’re reading was published in 2006].

Caption: the Greater noctule isn’t the only vesper bat known to capture and eat passerines. This behaviour has also been demonstrated for the Great evening bat Ia io. In the scene depicted here, a Great evening bat is about to capture a Sedge warbler Acrocephalus schoenobaenus. Image: Darren Naish.

Of course, bats don’t have it all their own way against birds. Raptors and owls are important predators of bats and some studies suggest that owls may account for as much as 10% of annual bat mortality (Altringham 2003). Some raptors are bat-killing specialists, like the Bat kite (or Bat hawk) Machaerhamphus alcinus of tropical Africa, SE Asia and New Guinea, and the South American Bat falcon Falco rufigularis. In fact raptor predation seems to be so important to bats that it appears to explain why bats don’t fly more during the daytime (Speakman 1991) and it may also explain why bats became nocturnal in the first place (Rydell & Speakman 1995).

That’ll do for now. The end of 2021 is in sight — it’s been an unusual year for sure, look for my review of events early in 2022…

Vesper bats have been covered at reasonable length on TetZoo before. See…

Introducing the second largest mammalian 'family': vesper bats, or vespertilionids, March 2011

Bent-winged bats: wide ranges, very weird wings (vesper bats part III), March 2011

Of southern African wing-gland bats, woolly bats, and the ones with tubular nostrils (vesper bats part IV), March 2011

The many, many mouse-eared bats, aka little brown bats, aka Myotis bats (vesper bats part V), March 2011

Long-eared bats proper: Plecotus and other plecotins (vesper bats part VI), March 2011

Robust jaws and a (sometimes) 'greenish' pelt: house bats (vesper bats part IX), April 2011

Antrozoins: pallid bats, Van Gelder's bat, Rhogeessa... Baeodon!! (vesper bats part XI), April 2011

Putting the 'perimyotines' well away from pips proper (vesper bats part XII), April 2011

Eptesicini: the serotines and their relatives (vesper bats part XIV), April 2011

Hypsugines: an assemblage of 'pipistrelle-like non-pipistrelles' (vesper bats part XV), April 2011

A list of enigmas: bamboo bats, frogs-head flyers, Rohu's bat and the false serotines (vesper bats part XVI), April 2011

Pipistrelles proper: little bats that glide, sing, swarm and lek (vesper bats part XVIII), April 2011

Bird predation, sexual segregation and fission-fusion societies: the amazing noctules (vesper bats part XIX), April 2011

A future for vesper bats? (vesper bats part XX - last in series), April 2011

This blog benefits from your support. Thank you to those who help via patreon!

Refs - -

Altringham, J. D. 2003. British Bats. HarperCollins, London.

Bontadina F. and Arlettaz R. 2003. A heap of feathers does not make a bat’s diet. Functional Ecology 17, 141-142.

Dondini, G. & Vergari, S. 2000. Carnivory in the greater noctule bat (Nyctalus lasiopterus) in Italy. Journal of Zoology 251, 233-236.

Dondini, G. & Vergari, S. 2004. Bats: bird-eaters or feather-eaters? A contribution to debate on Great noctule carnivory. Hystix 15, 86-88.

Francis, C. M., Anthony, E. L. P., Brunton, J. A. & Kunz, T. H. 1994. Lactation in male fruit bats. Nature 367, 691-692.

Ibáñez, C., Juste, J., García-Mudarra, J. L. & Agirre-Mendi, P. T. 2001. Bat predation on nocturnally migrating birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98, 9700-9702.

Ibáñez, C., Juste J., García-Mudarra J.L. & Agirre-Mendi P.T. 2003. Feathers as indicator of a bat’s diet: a reply to Bontadina & Arlettaz. Functional Ecology 17, 143-145.

Jones, K. E., Purvis, A., MacLarnon, A., Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P. & Simmons, N. B. 2002. A phylogenetic supertree of the bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera). Biological Reviews 77, 223-259.

Riskin, D. K. & Hermanson, J. W. 2005. Independent evolution of running in vampire bats. Nature 434, 292.

Rydell, J. & Speakman, J. R. 1995. Evolution of nocturnality in bats: potential competitors and predators during their early history. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 54, 183-191.

Speakman, J. R. 1991. Why do insectivorous bats in Britain not fly in daylight more frequently? Functional Ecology 5, 518-525.

Winter, Y., López, J. & von Helversen, O. 2003. Ultraviolet vision in a bat. Nature 425, 612-614.