For some years now, a prolific amateur herpetologist has published an absolutely extraordinary number of new taxonomic names for snakes, lizards and other reptiles…

Caption: lest we forget, the world is full of amazing snakes. Top row, left to right: Prairie or Western rattlesnake Crotalus viridis, Bornean keeled green pitviper Tropidolaemus subannulatus and Mole snake Pseudaspis cana. Lower row, left to right: Rock rattlesnake Crotalus lepidus, Rhinoceros viper Bitis nasicornis and Smooth-scaled death adder Acanthophis laevis. All photos by Wolfgang Wüster and used with permission.

In addition to naming well over 100 supposedly new snake and lizard genera, this individual has also produced taxonomic revisions of the world’s cobras, burrowing asps, vipers, rattlesnakes, water snakes, blindsnakes, pythons, crocodiles and so on. But, alas, his work is not of the careful, methodical, conservative and respected sort that you might associate with a specialized, dedicated amateur. Instead, his articles appear in his own, in-house, un-reviewed, decidedly non-technical publications. These are notoriously unscientific in style and content, and his taxonomic recommendations have been demonstrated to be problematic, frequently erroneous and often ridiculous. He has, for example, named many new taxa after his pet dogs.

In short, the new (and really terribly formulated) taxonomic names that this individual throws out at the global herpetological community represent what’s known as TAXONOMIC VANDALISM. We’re expected to use these names, and – indeed – they’re supposedly officially valid according to the letter of the law, yet they besmirch the field, litter the taxonomic registry with monstrosities, and cause working herpetologists to waste valuable time clearing up unnecessary messes.

Caption: Egyptian cobra Naja haje: included within the Naja subgenus Uraeus by Wallach et al. (2009) but given the new genus ‘Wellsus’ by Hoser. Hoser’s proposed name honours Richard Wells (on which, read on). Image: (c) Wolfgang Wüster, used with permission.

I am of course talking about Australian researcher and snake hobbyist Raymond Hoser. The charges against him are many. I’ve mentioned Hoser on a few previous occasions at Tet Zoo, most notably in the article on Australian freshwater crocodiles. It’s time to explore the issue in more depth. UPDATE: the article you’re reading here was originally published at Tetrapod Zoology ver 3 (the Scientific American years) in 2013 and includes several post-2013 updates.

A bit of required background: on taxonomic freedom and the Principle of Priority. One of the key principles of zoological taxonomy – the practice and science of naming animals – is what’s known as taxonomic freedom. It’s acknowledged that not all experts agree on how animals should be classified when it comes to where the boundaries are. Are a group of individuals all part of the same species, or do some actually represent a distinct, second species? Debates over species boundaries and how taxonomy should reflect those boundaries are commonplace and it can take a lot of work to sort them out, typically via statistical analyses of large numbers of individuals, molecular phylogenetics and so on.

But, whatever, if one or more authors do regard individuals within a group as a distinct taxon – here, we’re mostly interested in debates at the species level – they’re within their rights to act on this within the literature. ‘Taxonomic freedom’ allows this.

Caption: the African crocodile Crocodylus suchus, placed in the new genus ‘Oxycrocodylus’ by Hoser. What’s the etymology? The names honours Hoser’s dog, Oxyuranus (itself named after the Australian snake). Image: stuart Burns [sic], CC BY 2.0 (original here).

A well-established rule of the taxonomic naming system is the so-called Principle of Priority. Because people sometimes name the same organism more than once (sometimes because they don’t know about the work of their predecessors, sometimes because they think they’re dealing with a new taxon when they actually aren’t, and sometimes because they’re deliberately trying to beat other authors into print), it’s agreed that the very first name given to an organism is the one we have to stick with, even if that first name is deemed poorly chosen in some way.

There are special cases where a name can be overturned but, by and large, the Principle of Priority is pretty important and more or less guarantees a namer’s ‘place in history’. Remember that the full scientific name of an organism includes more than the organism’s name alone: Homo sapiens, for example, is properly Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758.

Caption: the Principle of Priority makes sense, but it’s not always our friend. We’re stuck, for example, with the name Basilosaurus for this extinct whale. Image: Tim, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

So, if you encounter an animal that you, personally, regard as worthy of distinct taxonomic recognition, you are – thanks to taxonomic freedom – within your rights to name it as such, and – thanks to the Principle of Priority – you’ve earned a place in history if you’re the first person to name the taxon in question. It’s assumed that you’ve correctly followed the rules set out in the ICZN (= International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) by the ICZN (= International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature). Yeah, same acronym. Once your new name is published, it’s essentially forever burned into history.

Caption: Hugh, what have you done? Hugh Edwin Strickland (1811-1853), as a young man of 26 at left (illustration by Francis William Wilkin, dating to 1858), and as an… older man at some later date. However, he died at age 42, so never got to be ‘old’ at all. In 1842, Strickland worked with others in the British Association to establish the Principle of Priority. Images in public domain.

What are these “rules set out in the ICZN”? As you can see for yourself at the ICZN site, a new name has to be published in a permanent, duplicable form that’s available to others, it has to be clearly stated as a new name, it has to be published within the context of the binomial (or binominal) system, and it must be established on a type specimen (a key reference specimen). Notably, many of the key ideas that we typically associate with the publication of scientific research – like standards of practice, an appropriate level of scholarship, and peer review – are, actually, not required by the ICZN. Perhaps surprisingly, the ICZN is actually quite lax about those venues that past muster when it comes to the publishing of new taxonomic names.

In other words, individuals can work within the mandates of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature even if their conclusions, proposals and work in general is problematic and unsatisfactory. They can still name new species that, technically speaking, are valid, available and (in theory) fixed due to the Principle of Priority.

Mega-prolific Raymond Hoser: one of the greatest herpetologists of all time! Back to Hoser. I don’t necessarily mean to denigrate Hoser’s research abilities, experience with snakes and other reptiles, or intelligence. As others before me have said, it’s obvious that he does have extensive, impressive, detailed knowledge of reptile diversity, anatomy and biology. But the fact is that he is very obviously ‘cheating’ his way through zoological nomenclature. Yes, he’s naming, and publishing umpteen new herpetological names. If you want some figures: between 2000 and September 2012 alone he named 89 tribes and subtribes, 113 genera, 64 subgenera, 25 species and 53 subspecies. That’s 76% of all new genera and subgenera named worldwide during that period (Kaiser et al. 2013). If these taxonomic recommendations and proposals were valid, they would make Hoser a more significant taxonomic force than most of the great explorer-herpetologists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Unlike the respected work produced by the experts of the past, however, Hoser’s is amazingly slapdash.

Caption: George Boulenger (1858-1937), Belgian-British zoologist and prolific describer of new amphibians, reptiles and other organisms. In all, he named over 2000 new species (556 of which are amphibians and 872 of which are reptiles). His impact on our knowledge has been enormous. Just a few of the species he named are featured here. Top row, left to right: African dwarf frog Hymenochirus boettgeri; New Caledonian gecko Rhacodactylus trachycephalus. Middle row, left to right: Stripe-tailed goanna Varanus caudolineatus; Sierra Leone water frog or Sabre-toothed frog Odontobatrachus natator; Blanford’s flying lizard Draco blanfordii. Lower right: Java grass lizard Takydromus khasiensis. Images: Boulenger image in public domain; James Gathany, public domain (original here); Lennart Hudel (CC BY 4.0, original here); Barej et al. (2015) (CC BY 4.0, original here); Haplochromis (CC BY-SA 3.0, original here); Rushenb (CC BY-SA 4.0, original here); Rohit Naniwadekar (CC BY-SA 4.0, original here).

In fact, the impression you get from Hoser’s articles – all appearing in his self-published Australasian Journal of Herpetology, and before that in several amateur* publications including Litteratura Serpentium and The Monitor – is that they’re written as much to piss off working herpetologists and to vent his own spleen as anything else. They are shockingly and hilariously unscientific. Many include long rants directed at officials and employees of local government as well as at qualified researchers. There are in fact so many cases of this non-scientific – in fact, truly amateurish, if not childish – practice in his articles that there are too many to recount.

* amateur here is intended to mean ‘not from a big publishing house’, nothing more.

Over the years, Hoser has had at least a bit of appropriate criticism (e.g., Aplin 1999, Wüster et al. 2001, Williams et al. 2006, Borrell 2007). He refers to those qualified herpetologists who criticize him and his work as “the truth haters”: the obvious implication being that he’s on the side of ‘The Truth’. Jeez, what is it with people on the fringes and their adherence to the notion that only they are seeing The Truth? Incidentally, Hoser frequently charges those of us who criticize him as ‘plagiarists’. He directed that specific charge at me after I wrote (unfavourably) about his crocodile article. I can only conclude that he doesn’t know what that word really means.

Caption: Australia sure has some amazing elapids. Given that Hoser claims to have the interests of the animals at heart, it’s bizarre that he defaces their taxonomy with horrible names that never honour the animals themselves (read on for examples). This is Oxyuranus microlepidotus, the Fierce snake or Inland taipan. Image: XLerate, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

If you’re curious about the technical shortcomings of Hoser’s taxonomic proposals, let’s look at a few of them. In order to make a claim for the distinctive nature of an alleged new taxon, you need to state those features that make it distinctive. In other words, you need to diagnose it. Hoser’s diagnoses are typically inadequate, contradictory, vague, or erroneous, sometimes referring to features that aren’t unique (example: the black labial markings in the proposed death adder species 'Acanthophis crotalusei'), and sometimes referring vaguely to work on scale counts, overall appearance or DNA that hasn’t been documented or published anywhere (Wüster et al. 2001, Kaiser et al. 2013).

Caption: death adders are incredible snakes. This is the Smooth-scaled death adder Acanthophis laevis of New Guinea and several islands to its west, including Ceram. In articles of 1998 and 2002, Hoser claimed the recognition of several additional taxa for populations otherwise considered part of this species. Their recognition was mostly rejected by Kaiser et al. (2013). Additional work is required to resolve the taxonomy of these snakes. Image: Petra Karstedt, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

Alleged new taxa have also been based on specimens where the ‘diagnostic’ characters clearly represent post-mortem distortion (see examples discussed in Kaiser et al. 2013). To add insult to injury, Hoser has sometimes named the same alleged new taxa on more than one occasion. 'Leiopython albertisi barkeri' Hoser, 2000 is the same as 'L. a. barkerorum' Hoser, 2009 which was then redescribed as if it were new in 2012. Similarly, 'Oxyuranus scutellatus barringeri' Hoser, 2002 is the same as 'O. s. andrewwilsoni' Hoser, 2009 (Kaiser et al. 2013). Many of the new names Hoser creates are incorrectly formulated: see Wüster et al. (2001) for a list and their amendments.

Slapping names on cladograms: it’s quick, it’s cheap, it’s dirty. Another thing that Hoser does is look at published cladograms, note cases where genera or species are shown as being non-monophyletic, and then name (in cursory, name-grabbing fashion) those lineages that don’t group with the type species of the given genus. This is known as nomenclatural harvesting (Denzer & Kaiser 2023).

Caption: Keeled slug snake Pareas carinatus. Close relatives of this species – conventionally included within Pareas – were put into the new genus 'Katrinahoserserpenea' by Hoser. Pareas is one of several genera within Pareidae, a poorly known and mostly tropical Asian colubroid snake group specialized for eating snails. Image: W. A. Djatmiko, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

There are numerous examples of this; they explain why Hoser has published such names as 'Katrinahoserserpenea' for certain Oriental slug-eating snakes (Hoser 2012a), 'Katrinahoserea' for the Green ratsnake (Hoser 2012b), 'Swileserpens' for the Pale-headed forest snake (Hoser 2012c), 'Michaelnicholsus' for members of the Madagascan hognosed snake group (Hoser 2012c), 'Lukefabaserpens' and 'Ginafabaserpenae' for some of the cat-eyed snakes (Hoser 2012d), 'Gregwedoshus' and 'Neilsonnemanus' for certain garter snakes (Hoser 2012e), 'Jackyhosernatrix' for certain natricine water snakes (Hoser 2012f), 'Sharonhoserea' for the Southern smooth snake (Hoser 2012f), and so on and on and on.

Note the terrible, terrible names that Hoser comes up with. Other notable word-monsters of his include 'Adelynhoserserpenae', 'Charlespiersonserpens', 'Euanedwardsserpens', 'Moseselfakharikukri', 'Trioanotyphlops' and 'Martinwellstyphlops'. If this doesn’t qualify as taxonomic vandalism, it’s difficult to know what does. Most (maybe all?) of Hoser’s taxonomic names are patronyms: names that honour people. That’s fine, but there has to be a limit to this sort of behaviour, especially when the namer is repeatedly naming things after the members of their own family and after their pets. As I said earlier, Hoser has named several taxa after his pet dogs, explaining at length how these noble canines have contributed more to herpetology than have the majority of the world’s researching academics (e.g., Hoser 2012g). Again, this is transparently taxonomic vandalism. A deliberate mockery of the field and the work of other researchers.

Caption: Hoser frequently points to cladograms (such as this one: this is the natricine section of Pyron et al.’s (2011) giant colubrid phylogeny) to support the taxonomic splits and renamings that he proposes. Yes, non-monophyly abounds in studies like this. But is it right to jump all over the cladogram and get to work slapping names all over the place? These things take time and a lot of work to sort out and do properly.

We do, of course, all know of cases where long-standing genera and/or species do indeed warrant revision. However, how are researchers meant to act when they spot these sorts of problems? My suggestion: once such a problem has been identified, good practice is to compile and run your own analysis, not to rush out a brief, non-illustrated article, the only purpose of which is to slap a name on a given lineage. If a researcher played the name-bagging name once in their career they might be forgiven (as I said, we all know of cases where new names are needed and people are just waiting for someone to come along and publish an update). But if they did this as a matter of course, again and again and again, typically naming new taxa after their family members and such, it would be pretty clear that they were deliberately and desperately ‘name-bagging’ in the hope for taxonomic immortality.

Incidentally, if, at this stage, you’re thinking that the taxonomic names we apply to snakes and other reptiles don’t really matter, think again. The whole reason we give names to things is so that we can talk about those things with other people. Confusion and disagreement are the opposite of useful when we’re dealing with conservation and summoning up the political and social will to protect animals and their environments. Furthermore, venomous snakes are a special case since a stable nomenclature known to people in the healthcare profession is a must; or it is, at least, if you want people to get the right antivenom after they get bitten.

Caption: the extremely variable Timber, Canebrake or Banded rattlesnake Crotalus horridus of eastern North America. This species can be regarded as ‘the original’ rattlesnake, the first one that European colonizers got to know and name scientifically. In Hoser’s proposed taxonomy, this is the only species retained within the subgenus Crotalus of his restricted version of the genus Crotalus. Images (clockwise from left): Tad Arensmeier, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here); Tanner Smida, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here); Glenn Bartolotti, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Has anybody, actually, yet become confused by the fact that spurious and problematic name changes have been suggested for any of these animals? After all, most working herpetologists have deliberately ignored and not used Hoser names. However, the Brazilian Society of Herpetologists adopted Hoser’s (2009) taxonomic arrangement for rattlesnakes, and this had a knock-on effect in the Brazilian literature. As argued by Wüster & Bérnils (2011), Hoser’s suggestions for rattlesnakes were redundant in the first place (they mostly involve subjectively sub-dividing an already monophyletic entity, namely Crotalus), are inconsistent with some published phylogenetic work, and are based on the assumption that certain parts of the phylogeny are resolved and ‘fixed’ for the foreseeable future. These are the technical problems; there are the additional ones related to the standing of Hoser’s articles in the first place (Wüster & Bérnils 2011).

Caption: the awesome Western diamondback rattlesnake Crotalus atrox, a species endemic to the southwestern USA and Mexico and among the largest rattlesnakes of them all (giant specimens can exceed 1.8 m). Hoser wants C. atrox to be recognized as the type species for his new genus ‘Hoserea’ (named for his wife). Image: Gary Stolz, United States Fish and Wildlife Service in public domain (original here).

What to do? Quality control should be integral to taxonomic publications. What can we actually do about taxonomic vandalism of this scale? Even the most lenient of liberal libertarians will agree that there’s a problem here: we clearly have an individual who isn’t using the same standards – or anything close to them – when publishing new names, and is insanely prolific to boot. Given what I said above about taxonomic freedom and the Principle of Priority, it’s essentially impossible to use the ICZN to discount or dismiss or ignore or strike off names that have been published and which meet the basic criteria discussed above. Or is it?

In 2013, a group of working herpetologists published a concise and very readable point-of-view piece on the subject in Herpetological Review (Kaiser et al. 2013). Note that the article is open access. Just to prove what a professional, ethical individual he is, Hoser somehow got hold of a version of this article before it was published and published it himself, in full (Hoser 2012h).

Caption: as we’ve seen, the ICZN is surprisingly lax about what is and what is not permissible when it comes to the acceptability of taxonomic names. That would be fine and good if all people publishing taxonomic names were doing work of a high, respectable standard. But they’re not. Communities of workers must therefore take a stand and state that there has to be a limit to what we can and will accept. Such is stated here in the title of Kaiser et al. (2013).

Predictably enough, Hoser (2013) later published another article in which, over more than 60 pages, he responded in characteristic fashion to Kaiser et al. (2013), referring to them as “alleged scientists” and “serial liars” throughout; he even (for reasons best known to himself) kept calling their article a “blog” (a blog is an updated, diary-style website: the word is not synonymous with ‘article’). Hoser’s 2013 article included a full reprinting of the final formatted version of Kaiser et al. (2013) from Herpetological Review. Hm, something tells me you’re not allowed to do that. You’ll be pleased to hear that I get a brief mention: I’m referred to as a “serial spammer”, as “a close friend of [Mark] O’Shea” and also as someone guilty of promoting the Kaiser et al. article on Twitter (Hoser 2013). Yup, guilty as charged, and proud of it (bar the erroneous “spammer” claim... again, does he know what that word actually means?).

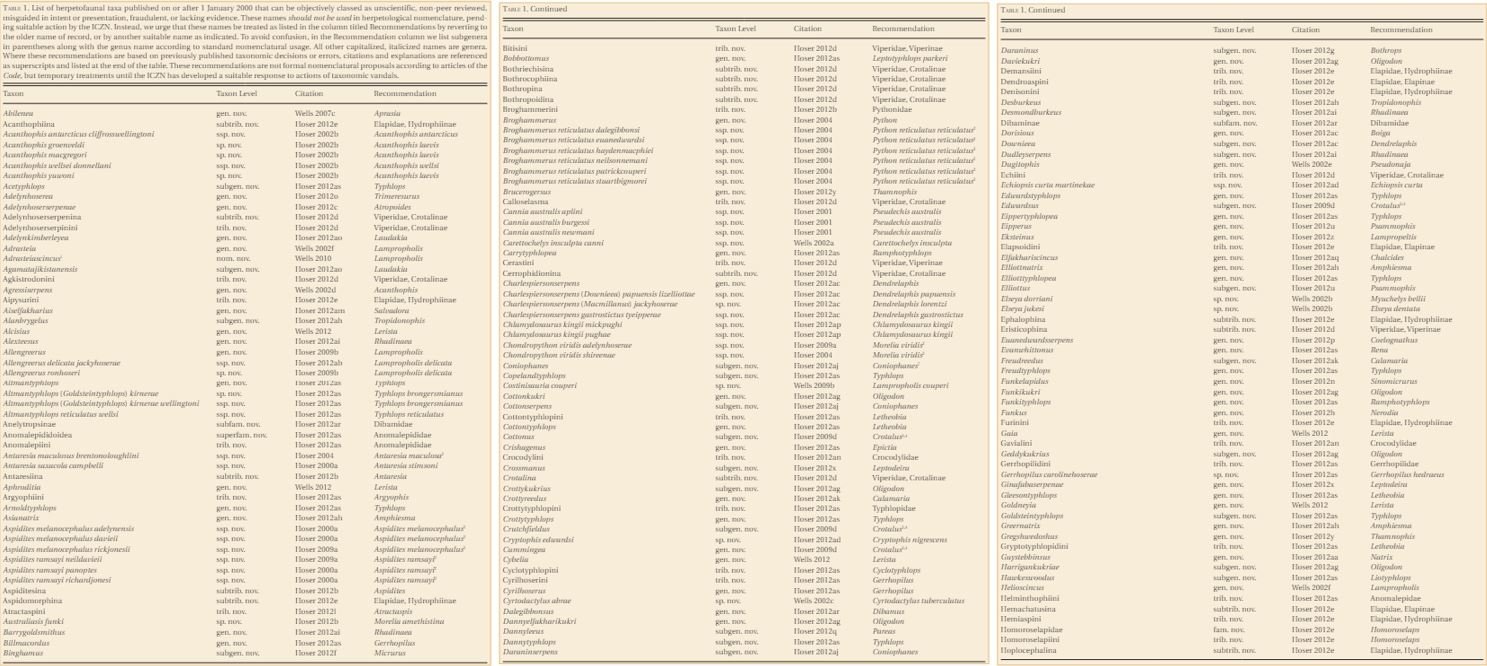

Caption: here are the first three pages of the six-page-long table of Hoser names compiled by Kaiser et al. (2013). See the paper for yourself: it’s open access. Kaiser et al. (2013) was – obviously – published more than ten years ago, and Hoser has since published numerous additional names. All should be ignored.

Kaiser et al. (2013) was not specifically about Hoser, since there have been (and are) several other authors who also self-publish taxonomic revisions where there’s little to no evidence of appropriate scholarship. Kaiser et al. (2013) also covered Richard Wells who, since 2000, has named over 25 new genera and numerous taxa in another self-published publication called Australian Biodiversity Record. Wells is notorious in the world of Australian herpetology for publishing two lengthy catalogues (co-authored with Ross Wellington) that made an enormous number of taxonomic recommendations for Australian reptiles and amphibians, few if any justified or supported in the way that’s normal for new systematic decisions (Wells & Wellington 1983, 1985).

An attempt by a group of over 150 Australian herpetologists to get the ICZN to suppress the names published by Wells and Wellington was unsuccessful: to repeat a point I made earlier, the ICZN more or less says that groups of researchers, not the Commission itself, have to police such problem areas themselves. The Wells and Wellington case is fairly well known and has been summarized and discussed numerous times in the literature (Grigg & Shine 1985, King & Miller 1985, Tyler 1985, 1988, Thulborn 1986, Ingram & Covacevich 1988, Hutchinson 1988, Iverson et al. 2001, Williams et al. 2006).

Caption: it might not surprise you to learn that Hoser behaves in a decidedly unhinged fashion on social media. He has numerous different accounts on Twitter/X (or, did last time I bothered to check) and is in the habit of reposting the same comment numerous times. He also makes a habit of smearing those who’ve criticized him in libellous fashion. For the record, I have no association with “fake science and fraud”, have no association with any “cohort found guilty of various criminal offences”, do not “control plenty of dodgy twitter accounts” and so on. These claims look an awful lot like projection.

With all of this in mind, Kaiser et al. (2013) argued that a measure of quality control is required if we’re to stop the literature being flooded with problem names appearing in unsatisfactory publications. The good news is that we already have such a system: namely, peer review. It makes perfect sense that new taxa should only be named in those published works that make it through the normal scientific channels and Kaiser et al. (2013) recommended that we introduce such a way of assessing the merits, or otherwise, of publications that include new taxonomic names. All published recommendations, as we’ve seen, are not created equal.

What about the Principle of Priority we looked at earlier? It’s well known that, in special cases, the ICZN will indeed rule against the use of certain names; the ICZN likes stability and the use of its rules, but it doesn’t like frivolity nor does it approve of new names that appear in non-technical publications. Kaiser et al. (2013) provided a long table that listed all the names that Hoser had published as of 2013, together with the recommended names that working herpetologists should use for the taxa in question.

Caption: the Black-necked spitting cobra Naja nigricollis, a species that’s partly served as the flashpoint for a call for action from the ICZN. N. nigricollis and its kin – the African spitting cobras – were given the subgeneric name Afronaja by Wallach et al. (2009), and ‘Spracklandus’ by Hoser in 2009. According to some interpretations, ‘Spracklandus’ was published first (Kaiser 2014), and thus should win out if the Principle of Priority were all that mattered. The point that’s now been made many times is that it isn’t all that should matter. It’s also not clear that ‘Spracklandus’ was published first anyway (Wüster et al. 2014). Image: Warren Klein, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Boycotting Hoser names. In short, it’s advised that herpetologists boycott Hoser’s names, and it’s hoped that the ICZN will eventually rule against their use entirely. In a 2015 appeal made to the ICZN, Rhodin et al. (2015) emphasized that none of Hoser’s works follow best practice, that his works basically do everything they can to undermine stability in herpetological taxonomy, and that numerous workers and organizations already boycott Hoser names. Ergo, the ICZN was asked to use its “plenary power to declare the Australasian Journal of Herpetology (AJH) Volumes 1-24 unavailable for nomenclatural purposes” (p. 77), and to make a statement asking that authors should adhere to the ICZN’s Code of Ethics (Rhodin et al. 2015).

The good news is that the ICZN did eventually publish an opinion on this (ICZN 2021). The bad news it that, par for the course, they declined to act, stating that “the Commission has declined to use its powers to confirm what is obvious” (ICZN 2021, p. 42). Again, this means that they bowed out of making a decision… though, that sure is some weird wording (“to confirm what is obvious”?).

Caption: a newspaper article from May 2013 that discusses some of the response to Hoser taxonomy, and notes some of the other charges against him. Full size version here.

Hoser’s other adventures. Elsewhere in his life, Hoser’s constant battles with local law enforcement – a subject I’m not interested in here – have led to his being found guilty of (and fined for) “scandalising the court”.

Then there’s the fact that he’s developed a technique of pinning down unanaesthetised venomous snakes on a table and cutting out their venom ducts (Hoser 2004). These snakes have been extensively handled (often in front of crowds) and Hoser is more than happy to let the snakes bite his daughters in order to demonstrate how safe they are. As you’ll find out if you check the wikipedia page on Hoser, he’s been convicted and fined for demonstrating with venomous snakes in close proximity to the public and had his commercial wildlife demonstrator license suspended. Hoser has also put himself forward as a candidate for local and state government on several occasions, including as recently as 2023, and has sued Australian companies for using the term ‘snake man’, which Hoser thinks he owns.

Caption: Hoser has appeared in the popular press a lot, for various reasons. This article from July 2012 discusses Hoser’s naming of the alleged new crocodile species ’Oopholis jackyhoserae’. It includes a few choice quotes from crocodile expert Professor Grahame Webb, including "The guy's a f*****g idiot". You can see the full article here.

Hard-working amateurs should be encouraged to contribute to science, not shunned or admonished, and it’s been stated on every occasion that unaffiliated researchers have frequently done, and do, sterling work. Fortunately, individuals like Hoser are rare and their research efforts are mostly recognized as the unsatisfactory, non-technical and bizarrely idiosyncratic contributions that they are. Nevertheless, the issue of taxonomic vandalism needs to be appreciated as widely as possible, and hopefully curtailed altogether.

UPDATE 1: this article was edited in March 2014 such that Hoser's names were taken out of italics and put in quote marks. This was done since otherwise it looked as if the Hoser names were proper scientific names on par with those used by others.

UPDATE 2: this article was originally published at Tetrapod Zoology ver 3 (the Scientific American years), but the current version of the article there is stripped of its images and paywalled. In order to make the article as widely accessible as possible, I’ve republished it here, with updates. An archived version of the 2013 article can be viewed here.

Hoser Taxonomy has been mentioned or discussed on a few previous occasions on Tet Zoo. See…

The Freshie: Australian crocodile, seemingly from the north (crocodiles part V), July 2012

Tetrapod Zoology enters its 8th year of operation, January 2013

Refs - -

Aplin, K. P. 1999. “Amateur” taxonomy in Australian herpetology – help or hindrance? Monitor 10 (2/3), 104-109.

Borrell, B. 2007. Linnaeus at 300: the big name hunters. Nature 446, 253-255.

Grigg, G. C. & Shine, R. 1985. An open letter to all herpetologists. Herpetological Review 16, 96-97.

Hoser, R. 2004. Surgical removal of venom glands in Australian elapid snakes: the creation of venomoids. The Herptile 29, 36-52.

Hoser, R. 2009. A reclassification of the rattlesnakes; species formerly exclusively referred to the genera Crotalus and Sistrurus. Australasian Journal of Herpetology 6, 1-21.

Hoser, R.. 2012a. A new genus of Asian snail-eating snake (Serpentes: Pareatidae). Australasian Journal of Herpetology 12, 12-14.

Hoser, R. 2012b. The dissolution of the genus Rhadinophis Vogt, 1922 (Serpentes: Colubrinae). Australasian Journal of Herpetology 12, 16-17.

Hoser, R. 2012c. A new genus and new subgenus of snakes from the South African region (Serpentes: Colubridae). Australasian Journal of Herpetology 12, 23-25.

Hoser, R. 2012d. A review of the South American snake genera Leptodeira and Imantodes including three new genera and two new subgenera (Serpentes: Dipsadidae: Imantodini). Australasian Journal of Herpetology 12, 40-47.

Hoser, R. 2012e. A review of the North American garter snakes genus Thamnophis Fitzinger, 1843 (Serpentes: Colubridae). Australasian Journal of Herpetology 12, 48-53.

Hoser, R. 2012f. A review of the taxonomy of the European colubrid snake genera Natrix and Coronella, with the creation of three new monotypic genera (Serpentes: Colubridae). Australasian Journal of Herpetology 12, 58-62.

Hoser, R. 2012g. A review of the taxonomy of the living crocodiles including the description of three new tribes, a new genus, and two new species. Australasian Journal of Herpetology 14, 9-16.

Hoser, R.. 2012h. Robust taxonomy and nomenclature based on good science escapes harsh fact-based criticism, but remains unable to escape an attack of lies and deception. Australasian Journal of Herpetology 14, 37-64.

Hoser, R.. 2013. The science of herpetology is built on evidence, ethics, quality publications and strict compliance with the rules of nomenclature. Australasian Journal of Herpetology 18, 2-79.

Hutchinson, M. N. 1988. Comments on the proposed suppression for nomenclature of three works by R. W. Wells and C. R. Wellington. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 45, 145.

Ingram, G. J. & Covacevich, J. 1988. Comments on the proposed suppression for nomenclature of three works by R. W. Wells and C. R. Wellington. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 45, 52.

International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. 2021. Opinion 2468 (Case 3601) – Spracklandus Hoser, 2009 (Reptilia, Serpentes, Elapidae) and Australasian Journal of Herpetology issues 1–24: confirmation of availability declined; Appendix A (Code of Ethics): not adopted as a formal criterion for ruling on Cases. The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 78, 42-45.

Iverson, J. B., Thomson, S. A. & Georges, A. 2001. Validity of taxonomic changes for turtles proposed by Wells and Wellington. Journal of Herpetology 35, 361-368.

King, M. & Miller, J. 1985. Letter to the editor. Herpetological Review 16, 4-5.

Pyron, R. A., Burbrink, F. T., Colli, G. R., Montes de Oca, A. N., Vitt, L. J., Kuczynski, C. A. & Wiens, J. J. 2011. The phylogeny of advanced snakes (Colubroidea), with discovery of a new subfamily and comparison of support methods for likelihood trees. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 58, 329-342.

Thulborn, T. 1986. Taxonomic tangles from Australia. Nature 321, 13-14.

Tyler, M. J. 1985. Nomenclature of the Australian herpetofauna: anarchy rules OK. Herpetological Review 16, 69.

Tyler, M. J. 1988. Comments on the proposed suppression for nomenclature of three works by R. W. Wells and C. R. Wellington. Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 45, 152.

Wells, R. W. & Wellington, C. R. 1983. A synopsis of the Class Reptilia in Australia. Australian Journal of Herpetology 1, 73-129.

Wells, R. W. & Wellington, C. R. 1985. A classification of the Amphibia and Reptilia of Australia. Australian Journal of Herpetology, Suppl. Ser. 1, 1-61.

Williams, D., Wüster, W. & Fry, B. G. 2006. The good, the bad and the ugly: Australian snake taxonomists and a history of the taxonomy of Australia’s venomous snakes. Toxicon 48, 919-930.

Wüster, W. & Bérnils, R. S. 2011. On the generic classification of the rattlesnakes, with special reference to the Neotropical Crotalus durissus complex (Squamata: Viperidae). Zoologia 28, 417-419.

Wüster, W., Broadley, D. G. & Wallach, V. 2014. Comments on Spracklandus Hoser, 2009 (Reptilia, Serpentes, ELAPIDAE): request for confirmation of the availability of the generic name and for the nomenclatural validation of the journal in which it was published (Case 3601; see BZN 70: 234–237). Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 71, 37-38.

Wüster, W., Bush, B., Keogh, J. S., O’Shea, M. & Shine, R. 2001. Taxonomic contributions in the “amateur” literature: comments on recent descriptions of new genera and species by Raymond Hoser. Litteratura Serpentium 21, 67-79, 86-91.