It’s time once again to look at a very interesting bunch of snakes….

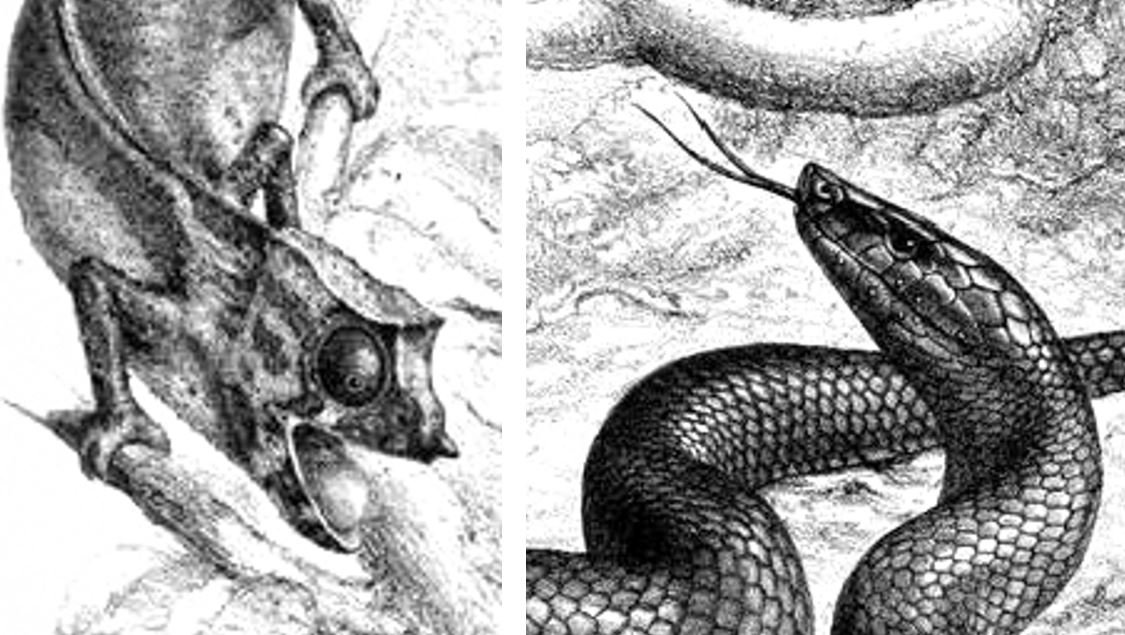

Caption: we’ll be seeing this illustration again… I really like it. Image: G. H. Ford, in the public domain.

In my continuing efforts to rescue and rehabilitate material now essentially lost due to the destruction of Tetrapod Zoology versions 2 and 3*, here’s another article on obscure snakes. And it has some degree of connection to the other snake-themed articles published here recently, which is good. The article here was originally published at ver 2 back in September 2010 and covers Bothrolycus ater, a relatively obscure African snake (go here for a wayback version of the original). At that time, I was super excited to learn that herpetologist and African snake expert Kate Jackson of Whitman College, Washington, had photographed this snake in living state, something that possibly hadn’t been done before. Dr Jackson very kindly gave permission for my use of these photos, and here we are. Below, please find an updated and tidied version of that 2010 article, and if you read it first time around... well, 2010 is a long time ago so you may as well read it again.

* Your reminder that the dead internet problem is a real and present danger, and yet another item on the list of bad things we need to worry about, sorry.

Caption: Bothrolycus in the flesh, photographed in the Republic of the Congo in 2010. Note the slightly reddish tint to the head, the shiny, smooth-scaled look, and the white spots around the jaws. Image: © K. Jackson.

Yes, this is Bothrolycus ater, one of so many snakes conventionally treated as a sort of ‘miscellaneous colubrid’. Colubridae, you’ll recall, is the snake group name mostly associated with racers and (rightly or not…) garter snakes, water snakes and kin. One of the first books I check when wanting to know more about obscure snakes is Chris Mattison’s The Encyclopedia of Snakes (Mattison 1998). Of this animal, Mattison lists it in his unsorted colubrid section, and states that it’s “A small snake about which almost nothing appears to be known” (p. 211). That’s it. Not encouraging. Incidentally, 2010 was the year during which I discovered – by complete coincidence – that Chris Mattison used to live about five minutes away from my house. Anyway… after a bit of research I discovered that – despite its obscure status – Bothrolycus isn’t that poorly known, and in fact should certainly be more familiar than it is.

Caption: at left, screengrab of the 2010 ancestor of the article you’re reading now. Yeah, the original article title was way wordier than the one I’ve gone for this time around. At right, Mattison (1998). It has served me well over the years.

Caption: this image of B. ater, by George Henry Ford, is from Günther’s original description. The chameleons are Spectral pygmy chameleons Rhampholeon spectrum, also known as the Western pygmy chameleon or Cameroon stumptail chameleon. I really like this entire illustration and wish that a clean white copy was available. I only have access to the very shady scan provided by the Biodiversity Heritage Library, which I’ve lightened as much as I can. Image in public domain.

The name Günther’s black snake is sometimes used for this species. Named by hyper-prolific German-born British zoologist Albert Günther in 1874, it’s from central Africa, its range including Cameroon, Gabon, Equatorial Guinea and the Republic of the Congo (Trape 1985, Lasso et al. 2002, Pauwels et al. 2006); Günther (1874) originally described it from Cameroon. The individual you see in the photos here was encountered by Kate in the Republic of the Congo in 2010, sadly in an area about to be strip-mined for iron ore.

In terms of habitat preference, Bothrolycus is an inhabitant of montane and sub-montane forest, and some studies indicate that it may be moderately common in some places. An interesting statement made by Georges Boulenger is that it’s semi-aquatic, which would be unusual for snakes of its sort. I haven’t seen this confirmed by other sources. It’s smooth-scaled (Moore & Jackson 2010) and can reach just over 41 cm. In adults, the blackish head is flecked with white, but in juveniles the top of the head and nape is cream-coloured (Loveridge 1936).

Caption: check out some of the great details in the George Ford illustration from above. The chameleon is totally not happy about seeing the snake, and the snake is beautifully depicted, with an excellently portrayed amount of sheen across its scales. Ford (1808-1876) joined the British Museum in 1837 and illustrated works on human anatomy, fishes, amphibians and reptiles. Images in the public domain.

Notable sexual dimorphism. I was surprised to learn that Bothrolycus has sometimes been cited as one of the only snakes where sexual dimorphism is obvious. Schmidt (1923) regarded the difference in size between the sexes as being “unusually pronounced” and “quite exceptional” while Davis (1936) noted that it was (to his knowledge) the only snake where males and females consistently exhibit different scale counts: the former exhibiting 17 and the latter 19 on the “anterior part of the body”. Boulenger (1919) was the first author to bring attention to this presence of obvious dimorphism.

A snake now regarded as a junior synonym of B. ater – that’s Pseudoboodon albopunctatus Anderson, 1901 – might owe its initial mis-description as a distinct taxon due to this sexual dimorphism, since I think (but am not 100% sure) that its holotype represents the opposite sex from the B. ater holotype. It’s moderately well known that the males and females of various animal species were initially described as different species… well, here’s an apparent case among snakes.

Caption: image of the Pseudoboodon albopunctatus holotype, from Anderson (1901). Compare it with the images of B. ater: note the pale spots on the labial scales and the pit in front of the eye. P. albopunctatus, by the way, was only one of several Pseudoboodon species. The genus (named by Mario Giacinto Peracca in 1897) is still a valid boaedontin taxon (four species are currently recognized). Image in public domain.

Anyway, since the above comments of the early 1900s were published, sexual dimorphism in snakes has become better known and is now understood to be quite widespread, including in size, mass and relative head size (Shine 1991). Nevertheless, given the apparently distinct – and historically significant (if you like) – sexual dimorphism of Bothrolycus, I’m surprised that the species is as little-mentioned as it is.

By the way, it’s obvious how virtually everything published about this snake comes to us from European scientists, often writing about museum specimens brought to European institutions by colonial explorers. What I’m getting at is that we essentially never hear what local people knew or know, or thought about or think about this snake. A striking animal such as this surely had some reputation to the people who lived and live alongside it. If such information is recorded in the literature, I’d love to know more.

What sort of snake is Bothrolycus? When I first wrote about this snake in 2010, the idea most familiar thanks to then-current literature was that Bothrolycus was part of the colubrid group Boodontinae (spelt Boaedontinae by some authors) (Dowling 1969, McDowell 1987, Zaher 1999, Lawson et al. 2005). This inclusion was historically based on hemipenial morphology: like other members of the group, each hemipenis in Bothrolycus is slightly bilobed and has centrolineal, bifurcating sulci spermatici and longitudinal rows of medium-sized spines that are connected by wavy, spinulate ridges (Zaher 1999). Yes, to be an expert on snake phylogeny and diversity, you have to be very familiar with male genitalia.

Caption: an Olive house snake Boaedon olivaceus, standing in as an exemplar for the lamprophiine genus Boaedon. Boaedon was mostly regarded as synonymous with Lamprophis – though the members of the two genera sure have a complex taxonomic history – until it was resurrected as valid by Kelly et al. (2009). Image: Erik Paterson, CC BY 2.0 (original here).

Since about 2010, Boodontinae/Boaeodontinae has undergone a name change: its type genus – Boaedon (the Cape house snake B. capensis and kin) – is almost definitely closely related to Lamprophis, meaning that the correct name for this group is Lamprophiinae. A version of this name (though written Lamprophes) was first published by Austrian zoologist Leopard Fitzinger in 1843, whereas Boodontinae wasn’t published until 1893 (by E. D. Cope) (Kelly et al. 2009).

Caption: this illustration, by Joseph Smit and published in 1887, depicts Fisk’s house snake Lamprophis fiskii and accompanied Boulenger’s original description of this species. Under the current, restricted use of the name, Lamprophis only includes three extant species. Image in public domain.

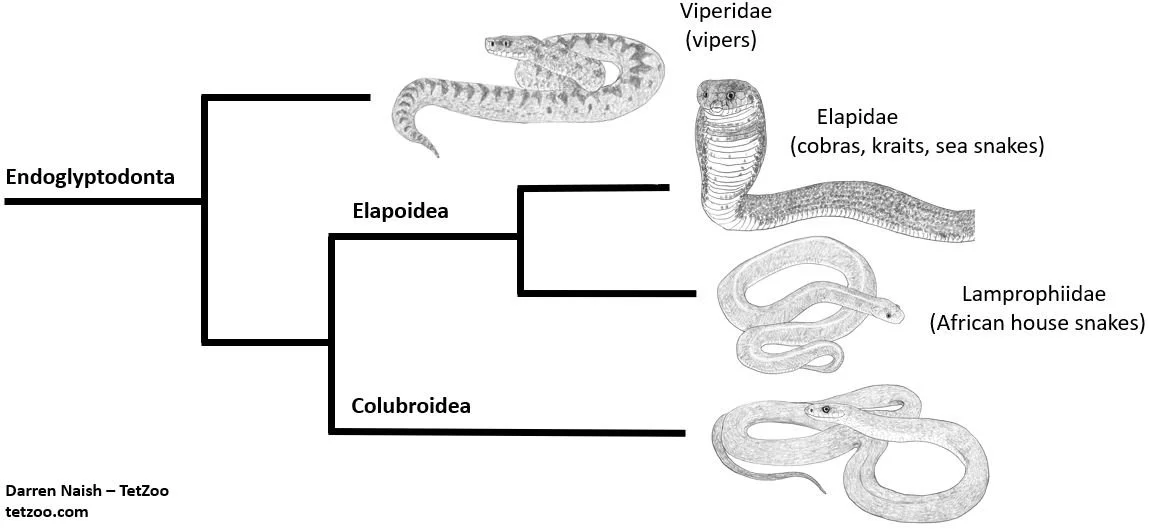

And as you’ll know if you read the other recent snake articles here, both Lamprophiinae and Lamprophiidae are now in general use in the snake literature, recent studies agreeing that this is an important clade within Elapoidea: it is not close to Colubridae, but instead to Elapidae (the cobras, kraits, sea snakes and so on) (Pinou et al. 2004, Lawson et al. 2005, Kelly et al. 2009, Pyron et al. 2011, 2013, Zaher et al. 2009, 2019, Figueroa et al. 2016, Das et al. 2023). If Bothrolycus is a lamprophiine… well, that puts an end to our need to refer to it as a ‘colubrid’. By the way, lamprophiines/lamprophiids have sometimes been vernacularly termed ‘house snakes’ (since that name is attached to the Boaedon and Lamprophis species that form the ‘core’ of the group) but ‘African nocturnal snakes’ was suggested by Kelly et al. (2009).

Caption: here’s that very simplified cladogram again, showing relationships among the main endoglyptodont groups. Elapoidea includes numerous lineages and views differ on which should and should not be included within Lamprophiidae. The topology shown here is consistent with several recent studies, but the taxonomy specifically follows that of Zaher et al. (2009). Image: this uses images created for the textbook I’m putting together. More on that on patreon.

And… is Bothrolycus a lamprophiine? Zaher et al. (2009) supported this on the basis of hemipenial morphology, and it’s since been supported in molecular studies. Specifically, Kelly et al. (2011), Pyron et al. (2011, 2013), Figueroa et al. (2016), Portillo et al. (2019), Zaher et al. (2019) and Tiutenko et al. (2022) all found Bothrolycus to be close to Lamprophis and Boaedon, and thus unambiguously within Lamprophiinae even in the very strictest sense of that name. All of these studies found a Bothrolycus + Bothrophthalmus clade as the sister-group to a Lamprophis + Boaedon clade, this whole lot corresponding to Boaedontini as used by Dowling (1969).

Bothrophthalmus, if you’re wondering, includes the Red-striped black snake Bo. lineatus of tropical Africa, its range extending from Guinea in the west to Uganda in the east and Angola in the south. Conventionally, there’s only one Bothrophthalmus species. But that might be wrong. I should also mention that Tiutenko et al. (2022) recognized the so-called Ethiopian house snake – conventionally Boodon erlangeri – as a boaedontin close to the Bothrolycus + Bothrophthalmus clade and gave it the new generic name Bofa. I tell you, caenophidian snake phylogenetics really is where it’s at.

The big deal about Bothrolycus. One thing makes Bothrolycus a particularly special snake, and it’s not its sexual dimorphism or its position within phylogeny. It’s the presence of unusual openings on the side of the face, located just in front of the eyes and referred to by Anderson (1901) as elongate deep loreal pits. You should be able to make them out in Kate’s photos.

Caption: that live Bothrolycus individual again, photographed in the Republic of the Congo in 2010. An interesting anatomical detail here is that the maxillary tooth tips are partly visible, perhaps because the snake has exposed these as a threat display. I owe thanks to snake expert John Scanlon for the following observation: “And those tips form two distinct groups: long fang-like teeth at the front, and shorter ones more closely spaced posteriorly. All those teeth are on the maxilla; this pattern is rather like elapid dentition, and probably not by coincidence. And the ‘wolf’ reference in the name is presumably due to the large canine-like anterior teeth, as in several other snake genera with ‘lyco’ names”. Image: © K. Jackson.

If you know snakes, you’ll no doubt be thinking of the facial pits present in vipers, pythons and boas. These house thermoreceptors and allow the snakes to detect heat sources, these typically being warm-bodied prey animals. So… do the pits in Bothrolycus also contain thermoreceptors? Does this African elapoid also use heat-detection to find prey? I don’t know the answers to these questions and, so far as I can tell, nor does anyone. In fact, I haven’t seen any information on the diet or feeding behaviour of this snake. If Bothrolycus does possess heat-detecting pits, then these remarkable structures must have evolved in yet another snake group.

Caption: closeup of the snake’s right side, this time showing the loreal pit and also the white facial spots in detail. The latter are restricted to the labial scales and are arranged approximately symmetrically on both upper and lower jaws. Image: © K. Jackson.

I started this article by noting how obscure Bothrolycus is, and you might recall that I quoted certain sources as stating that nothing, essentially, is known about this snake. But now that we’re at the end of an article that includes over 1620 words, we may ask: does the fact that it’s obscure mean that there’s nothing to say about it? I think not.

I need to finish by expressing massive thanks to Dr Kate Jackson for supplying the Bothrolycus images in the first place (visit Kate’s webpage). For previous articles on squamates, see…

Cambodia: now with dibamids!, May 2011

The Tet Zoo Guide to Mastigures, August 2018

The Remarkable Basilisks, May 2023

Do Lizards Really Have ‘Mite Pockets’?, March 2024

Meeting Lake Zacapu’s Garter Snake, March 2024

Ray Hoser, Number 1 Taxonomic Vandal, May 2024

The Mysterious Dibamids, May 2024

Refs – -

Anderson, L. G. 1901. Some new species of snakes from Cameroon and South America, belonging to the collections of the Royal Museum in Stockholm. Bihang Till Köngl. Svenska Vetenskäps-Akadeillens Handlingar 4, 3-26.

Boulenger, G. A. 1919. Un cas interessant de dimorphisme sexuel chez un serpent africain (Bothrolycus ater Günther). Comptes Rendu de l’Academie des Sciences, Paris168, 666-669.

Das, S., Greenbaum, E., Meiri, S., Bauer, A. M., Burbrink, F. T., Raxworthy, C. J., Weinell, J. L., Brown, R. M., Brecko, J., Pauwels, O. S. G., Rabibisoa, N., Raselimanana, A. P. & Merilä, J. 2023. Ultraconserved elements-based phylogenomic systematics of the snake superfamily Elapoidea, with the description of a new Afro-Asian family. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 180, doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2022.107700

Davis, D. D. 1936. Courtship and mating behaviour in snakes. Zoological Series of Field Museum of Natural History 22, 257-290.

Dowling, H. G. 1969. Relations of some African colubrid snakes. Copeia 1969, 234-242.

Günther, A. 1874. Descriptions of some new or imperfectly known species of reptiles from the Camaroon [sic] Mountains. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 42, 442-445.

Kelly, C. M. R., Barker, N. P., Villet, M. H. & Broadley, D. G. 2009. Phylogeny, biogeography and classification of the snake Superfamily Elapoidea: a rapid radiation in the late Eocene. Cladistics 25, 38-63.

Kelly, C. M. R., Branch, W. R., Broadley, D. G., Barker, N. P. & Villet, M. H. 2011. Molecular systematics of the African snake family Lamprophiidae Fitzinger, 1843 (Serpentes: Elapoidea), with particular focus on the genera Lamprophis Fitzinger 1843 and Mehelya Csiki 1903. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 58, 415-426.

Lasso, C. A., Rial, A. I., Castroviejo, J. & De la Riva, I. 2002. Herpetofauna del Parque Nacional de Monte Alén (Río Muni, Guinea Ecuatorial). Graellsia 58, 21-34.

Lawson, R., Slowinski, J. B., Crother, B. I. & Burbrink, F. T. 2005. Phylogeny of the Colubroidea (Serpentes): new evidence from mitochondrial and nuclear genes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 37, 581-601.

Loveridge, A. 1936. African Reptiles and amphibians in field museum of natural history. Field Museum of Natural History – Zoology 22, 1-111.

Mattison, C. 1998. The Encyclopedia of Snakes. Blandford, London.

McDowell, S. B. 1987. Systematics. In Seigel, R. A., Collins, J. T. & Novak, S. S. (eds) Snakes: Ecology & Evolutionary Biology. Macmillan (New York), pp. 3-49.

Moore, K. & Jackson, K. 2010. A quantitative analysis of two scale characters in snakes. Amphibia-Reptilia 31, 175-182.

Pauwels, O. S. G. Burger, M., Branch, W. R., Tobi, E., Yoga, J.-A., & Mikolo, E.-N. 2006. Reptiles of the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas, Southwestern Gabon. Bulletin of the Biological Society of Washington 12, 309-318.

Pinou, T., Vicario, S., Marschner, M. & Caccone, A. 2004. Relict snakes of North America and their relationships within Caenophidia, using likelihood-based Bayesian methods on mitochondrial sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 32, 563-574.

Pyron, R. A., Burbrink, F. T., Colli, G. R., Montes de Oca, A. N., Vitt, L. J., Kuczynski, C. A. & Wiens, J. J. 2011. The phylogeny of advanced snakes (Colubroidea), with discovery of a new subfamily and comparison of support methods for likelihood trees. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 58, 329-342.

Schmidt, K. P. 1923. Contributions to the herpetology of the Belgian Congo based on the collection of the American Museum Congo Expedition, 1909-1915. Part II. Snakes. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 49, 1-146.

Shine, R. 1991. Intersexual dietary divergence and the evolution of sexual dimorphism in snakes. The American Naturalist 138 103-122.

Tiutenko, A., Koch, C., Pabijan, M. & Zinenko, O. 2022. Generic affinities of African house snakes revised: a new genus for Boodon erlangeri (Serpentes: Elapoidea: Lamprophiidae: Lamprophiinae). Salamandra 58, 235-262.

Trape, J. F. 1985. Les serpents de la région de Dimonika (Mayombe, République Populaire du Congo). Revue De Zoologie Africaine 99, 135-140.

Zaher, H. 1999. Hemipenial morphology of the South American xenodontine snakes, with a proposal for a monophyletic Xenodontinae and a reappraisal of colubroid hemipenes. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 240, 1-168.