Once more I must resort to plundering stuff from the archives, this time an article from TetZoo ver 2, originally published in July 2008 (and available here at wayback machine). Today: the kogiid sperm whales!

Caption: reconstruction of a hunting Pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps about to capture a mysid crustacean. Image: Markus Bühler, original here.

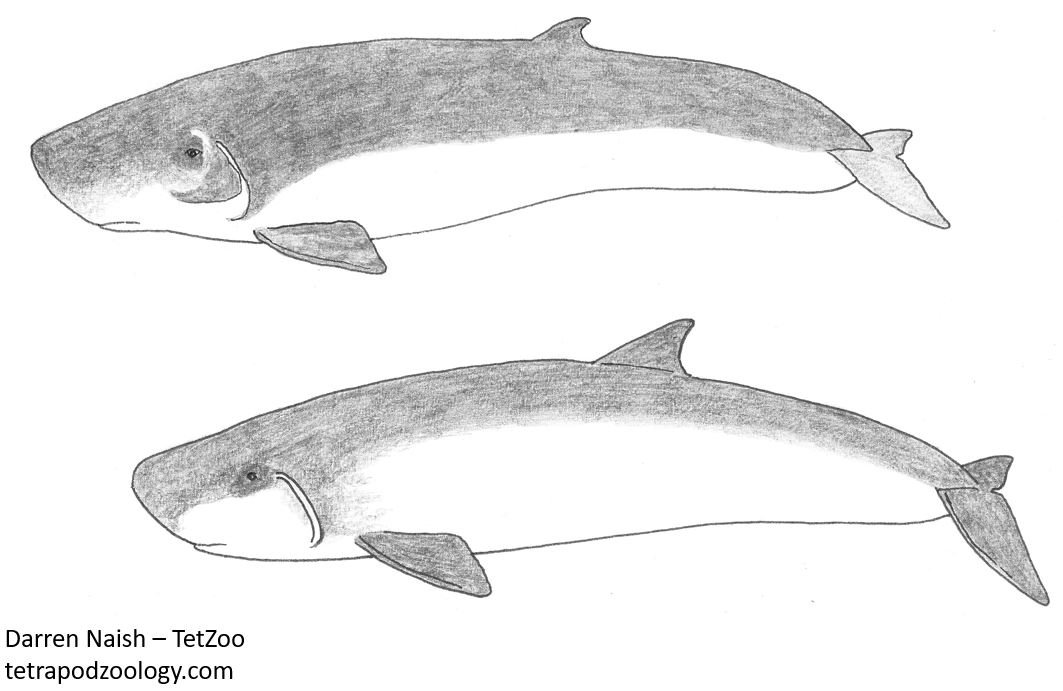

There are two currently recognised (extant) Kogia species: the Pygmy sperm whale K. breviceps and Dwarf sperm whale K. sima, though genetic evidence suggests that K. sima might actually be two species (Chivers et al. 2005). K. sima was known as K. simus until recently. K. breviceps and K. sima differ in that K. sima has a shorter snout, and a much larger, more anteriorly located dorsal fin. K. breviceps lacks functional upper jaw teeth, but K. sima can sometimes have up to three pairs of small maxillary teeth (though I’ve seen pictures – there’s one in Berta & Sumich (1999) – that show K. breviceps with maxillary teeth too). At 3–4 m long, the Pygmy sperm whale is also bigger than the Dwarf sperm whale, which ranges from 2.1–2.7 m.

Caption: K. breviceps skull in left lateral view. Note short rostrum, apparent change between long axes of rostrum and cranium, lack of teeth and shortness of cranium overall. Image: (c) Natural History Museum, London/Colin McHenry.

The rostrum of Kogia is proportionally the shortest of any cetacean, with some of the bones that usually form the skull roof (the nasals and supraoccipital) being either squashed up and fused, or absent. It seems that, as the rostrum shortened, the bones forming the anterolateral margins of the orbits (the lacrimals, the posterolateral parts of the maxillae, and the anterior parts of the frontals) came to overlap the base of the rostrum, thereby closing up the antorbital notches such that they now remain only as long slits (in the fossil kogiid Scaphokogia from the Miocene, the antorbital notches form very long slits, with that on the left side being about equivalent in length to the width of the base of the rostrum). The bones of the mandibles are apparently paper-thin and the thin, sharply pointed teeth (which lack enamel) were regarded by Handley (1966) as being “strongly reminiscent of the teeth of pythons”.

My long-standing friend and associate Markus Bühler has written a good article about kogiid teeth and jaws and their functions: go here.

Caption: lower jaw of K. breviceps in right lateral view. Image: (c) Natural History Museum, London/Colin McHenry.

The most obviously weird thing about the skull, however, is the presence of a large, rounded, supracranial basin on the skull roof. The presence of a wide, rounded supracranial basin, a condition termed scaphidiomorphy, is common to all physeteroids and is a synapomorphy of the clade (Muizon 1991). The basin houses a unique structure called the spermaceti organ, and while I’d like to discuss ideas on its function I’m not going to as that would easily add 1000 words to what was meant to be a short article.

Caption: at left, the skull of K. breviceps in dorsal view (note the highly asymmetrical cranial basin). At right: skull of the extinct Scaphokogia in dorsal view, from Muizon (1988). Images: (c) Natural History Museum, London/Colin McHenry; Muizon (1988).

The supracranial basin of Kogia is strongly asymmetrical and divided along the midline by a septum formed from the asymmetrical premaxillae: the left premaxilla only extends as far as the left naris, while the right premaxilla extends all the way to the vertex, surrounding the right naris entirely and sporting a mid-line crest in the nasal region that then leans over to the left (Schulte 1917, Nagorsen 1985). The right naris is small and sub-rounded while the left one is large and oval. Cranial asymmetry is actually the norm in crown-odontocetes, only being absent in Pontoporia (the franciscana), though a few other taxa (like Orcinus) are relatively symmetrical compared to their relatives (Ness 1967).

Caption: K. breviceps (above) and K. sima. Note the similar ‘false gill’ markings but the bigger dorsal fin and smaller size of K. sima. Image: Darren Naish.

Kogia doesn’t just have a weird skull; it’s one of the weirdest cetaceans all round. Its head is small for the size of the animal, being only 14-16% of total length, and its flippers are proportionally small as well, with unossified phalanges and carpals. Its under-slung mouth has been described by some as shark-like, and it has peculiar ‘false gill’ markings on the side of the head. I have a vague recollection of reading a proposal that it may even try to mimic sharks, but I can’t find this in the literature and wouldn’t take it too seriously anyway. Its neck vertebrae are all fused together and its tail flukes are apparently a lot floppier than those of other cetaceans. I also think it looks pretty scary: the picture below shows the head of a stranded K. sima, reported from Italy by Bortolotto et al. (2003).

Caption: the head of a stranded K. sima, reported from Italy by Bortolotto et al. (2003). The version included in the original publication is small and low-res, and thus so is the version used here.

Behaviour and biology, briefly. Kogia does some weird behavioural stuff. K. sima has been reported to release a reddish anal fluid (presumably faeces) which then spreads out in the water to form a cloud of about 100 m sq, and to then hide in the middle of the cloud (Scott & Cordaro 1987). This is of course irresistibly comparable to what cephalopods do, which is all the more ironic given that kogiids are cephalopod predators. Again, Markus Bühler has written an especially good and comprehensive article on this subject: The weird little whales that hide within a cloud of their gut fluid.

They’ve also been reported to be surprisingly aggressive, ramming boats and leaping towards them when trapped in seine nets. This is somewhat reminiscent of what Physeter – the big sperm whale – does, though its size of course means that its boat-ramming activities are better documented. Incidentally, it may not be a coincidence that sperm whales big and small (1) have a spermaceti organ and (2) indulge in head-ramming. More on this another time [UPDATE: well, that worked out well. Only 14 years have passed].

As for feeding, Kogia species use rapid jaw-opening, powerful retraction of the tongue and expansion of the throat to generate negative pressures when suction-feeding (Bloodworth & Marshall 2005). I’ve been mentioning suction-feeding on and off at TetZoo for ages now and, again, will elaborate on it at some other time [UPDATE… err, yeah].

Caption: K. sima individuals photographed close to the Comoros. That profile looks a bit like that of a globicephaline dolphin, but the behaviour is very different. Oh to see Kogia in life. Images: Marco Bonato (originals here), CC BY-SA 4.0.

That name. Incidentally, I personally quite like the name Kogia. It seems that our predecessors did not share this opinion however. Writing in 1854, W. S. Wall “regretted that a barbarous and unmeaning name like Kogia should have been admitted into the nomenclature of so classical a group as the cetacea”. Richard Owen agreed with Wall and used the name that Wall proposed, Euphysetes Wall, 1851, over Kogia Gray, 1846, writing of Kogia in 1870 that “I have that confidence in the common-sense and good judgment of my fellow countrymen and labourers in philosophical zoology which leads me to anticipate a tacit burial and oblivion of the barbarous and undefined generic names with which the fair edifice begun by Linnaeus has been defined”. This was all recounted by Gill (1871) who, while using the name Kogia because of its nomenclatural priority, recognised “the justness of the criticisms upon it” (p. 740). Oh, come on, the name ‘Kogia‘ is really not that bad.

Caption: Kogia can breach! This is a K. sima. Image: Robert Pitman, in public domain (original here).

Cetaceans have been covered at length on TetZoo before – mostly at ver 2 and ver 3 – but these articles are now all but useless since all of their images have been removed, hence the links here to versions at wayback machine. Over time, I aim to build up a large number of cetacean-themed articles here at ver 4 [UPDATE: hmm, that’s not going so well….].

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008

Scaphokogia!, July 2008

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015

Whale Watching in the Bay of Biscay, August 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 1, September 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 2, September 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 3, December 2019

Refs – -

Berta, A. & Sumich, J. L. 1999. Marine Mammals: Evolutionary Biology. Academic Press, San Diego.

Bloodworth, B. & Marshall, C. D. 2005. Feeding kinematics of Kogia and Tursiops (Odontoceti: Cetacea): characterization of suction and ram feeding. The Journal of Experimental Biology 208, 3721-3730.

Bortolotto, A., Papini, L., Insacco, G., Gili, C., Tumino, G., Mazzariol, S., Pavan, G. & Cozzi, B. 2003. First record of a dwarf sperm whale, Kogia sima (Owen, 1866) stranded alive along the coasts [sic] of Italy. In 31st Symposium of the European Association for Aquatic Mammals. Tenerife.

Chivers, S. J., LeDuc, R. G., Robertson, K. M., Barros, N. B. & Dizon, A. E. 2005. Genetic variation of Kogia spp. with preliminary evidence for two species of Kogia sima. Marine Mammal Science 21, 619-634.

Gill, T. 1871. The sperm whales, giant and pygmy. The American Naturalist 4, 725-743.

Handley, C. O. 1966. A synopsis of the genus Kogia (pygmy sperm whales). In Norris, K. S. (ed) Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. University of California Press (Berkeley & Los Angeles), pp. 62-69.

Muizon, C. de 1988. Les vertebras de la Formation Pisco (Pérou). Troisième partie: des Odontocètes (Cetacea, Mammalia) du Miocène. Travaux de l’Institut Francais d’Études Andines 17, 1-244.

Muizon, C. de 1991. A new Ziphiidae (Cetacea) from the Early Miocene of Washington State (USA) and phylogenetic analysis of the major groups of odontocetes. Bulletin du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (4e sér.) 12, 279-326.

Nagorsen, D. 1985. Kogia simus. Mammalian Species 239, 1-6.

Ness, A. R. 1967. A measure of asymmetry of the skulls of odontocete whales. Journal of Zoology 153, 209-221.

Schulte, H. von W. 1917. The skull of Kogia breviceps Blainv. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 37, 361-404.

Scott, M. D. & Cordaro, J. G. 1987. Behavioral observations of the dwarf sperm whale, Kogia simus. Marine Mammal Science 3, 353-354.