Do you know this book? If the answer is yes, you might enjoy the following…

Over the past several months it’s become clear to me that a book I co-authored in 2001 – Dorling Kindersley’s Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Life, sold in some regions as Dinosaur Encyclopedia: From Dinosaurs to the Dawn of Man (Lambert et al. 2001) – is today considered something of a classic; as a book that was influential and inspirational to many people who are now adult and are sometimes even involved in palaeontology or the life or earth sciences more broadly. It might be correct to imagine the book as my most important publication so far.

Caption: the two most familiar covers of Lambert et al. (2001). There’s also a version with a Triceratops skull on the cover.

In view of this, I thought it would be interesting to share my recollections on the construction of the book, to discuss how it came together, and to review the trials and tribulations and ups and downs of this massive, complex project.

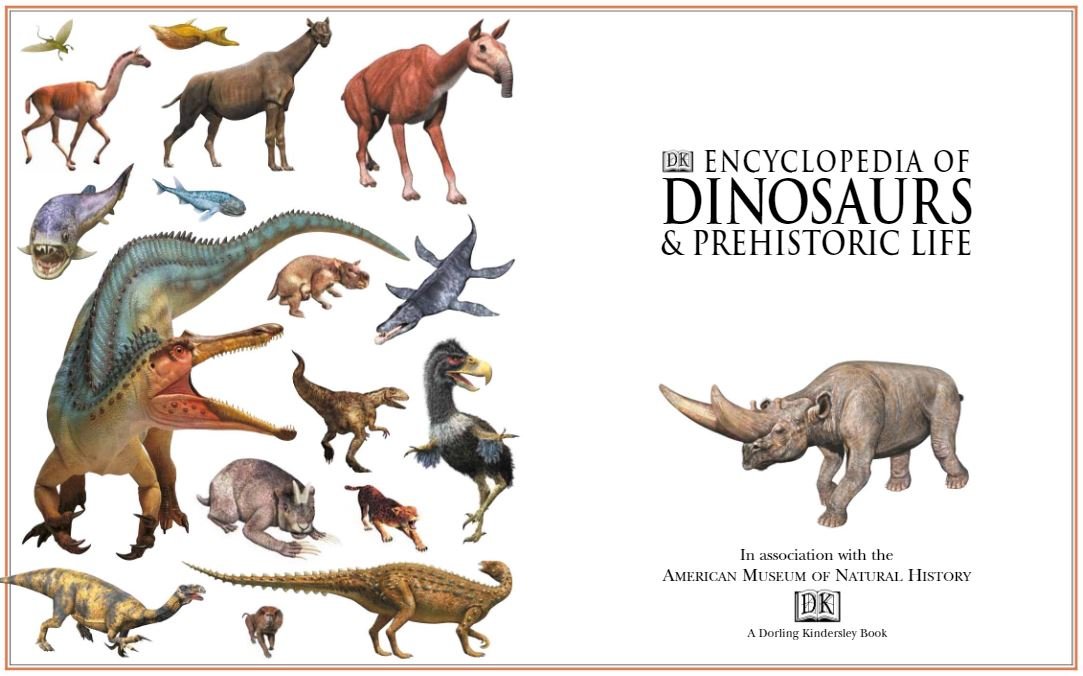

Caption: intro pages to the book, showing certain images that appear later in the book. A lot of work went into advising and helping the artists on these reconstructions and some are more of a success than others. I was quite pleased with how the pliosaur turned out (the blue animal with flippers): a real contrast to the original version, and the Paraceratherium (at upper middle) is not bad either. More on the art below…

The Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Life was mostly written in late 2000 and early 2001. At this point in my career, my other books* had been won via my connection with my Phd supervisor (Dr David Martill). The Dorling Kindersley Encyclopedia arrived via an entirely different connection, this being my long-standing correspondence with author David Lambert, who I’d been writing to since 1995. David had been working with the DK team for a few months already, felt that an additional author was needed and, I’m pleased to say, put my name forward as a potential collaborator. Ever desperate for paying work (and in a bad financial position at the time), I said yes. I had the required meetings in London at Dorling Kindersley’s former Covent Garden office, contracts were signed in September and October 2000, and to work I went. I have, incidentally, lost touch with David in recent years and know nothing of his current status.

* At the time, they were the BBC’s Walking With Dinosaurs: the Evidence (Martill & Naish 2000) and Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight (Martill & Naish 2001). The first of those was completed during the summer of 2000, and the second in the September of 2000.

Caption: at left, the only photo I think I’ve seen of author David Lambert (it features on the dustjacket of his 1993 The Ultimate Dinosaur Book, also from Dorling Kindersley). At right. David’s Collins Guide to Dinosaurs of 1983, one of my favourite childhood books.

Here we come to the practicalities of working on a project as grand as this. In 2000 and 2001, I was a PhD student at the University of Portsmouth. I was self-funded, this meaning that I had to earn money via a normal job (one in retail) at the same time as doing my studies; this, in turn, meant that I could only spend time on academic and authoring pursuits every other day, here and there. My wife and I (we were living in a tiny flat at the time) didn’t have internet at home, so I was isolated and unable to deal with jobs and queries when there. I had to get to the university in order for things to happen. I’d arrive (always later than planned due to constant thwarting by British public transport) and then immediately have to run around like an idiot as I aimed to catch up with correspondence and keep up with all the work. Looking back at it now, I don’t know how I did it, let alone manage to complete my PhD studies at the same time.

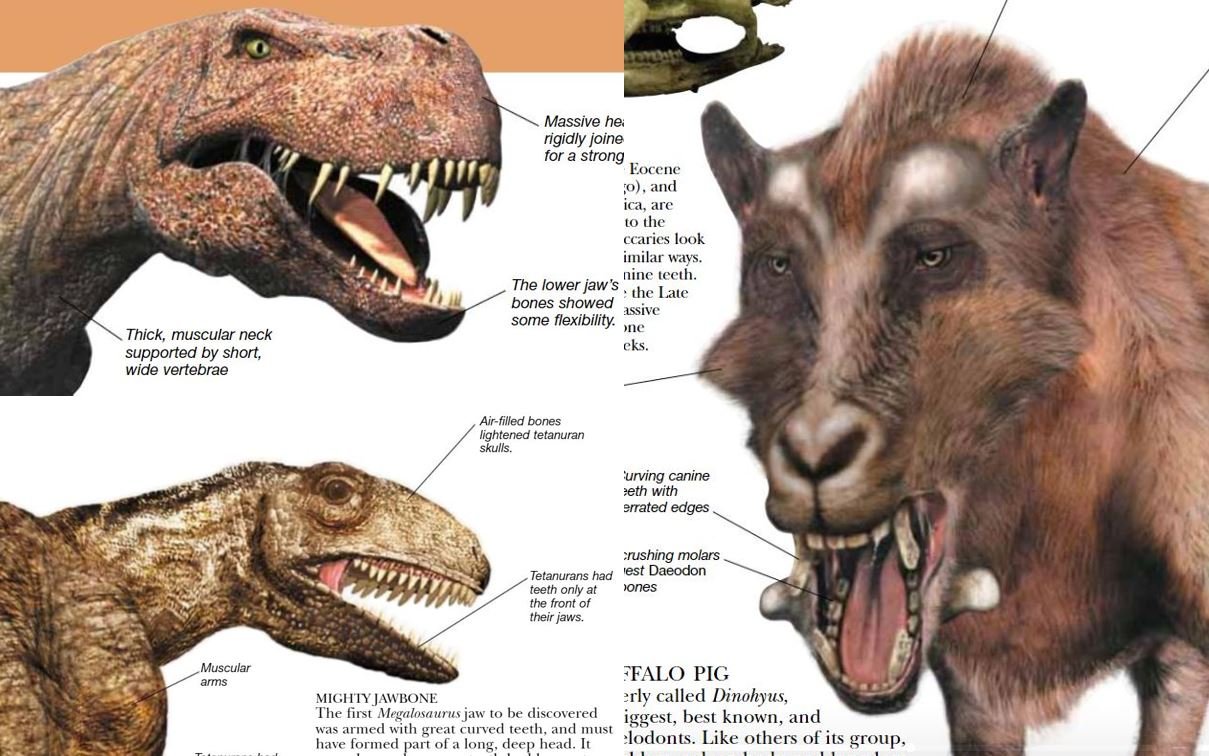

Caption: two spreads as they appear in the final product. There’s a lot of good content here.

The project being so huge, the aim was to complete a batch of related sections before moving to the next. This means that you find yourself ‘living’ in the world of one particular collection of animals – say, Paleozoic tetrapods or hoofed mammals – before saying goodbye and moving to the next. I was in charge of Paleozoic vertebrates, marine reptiles, mammals and other synapsids, much of the introductory material (on evolution and fossils in general), the end matter (on fieldwork, the history of the fossil record and so on) and on the cladograms that introduced each major section. Perhaps surprisingly, I mostly didn’t do the dinosaurs. They were David’s remit. I am not entirely sure which sections Liz Wyse was in charge of but there’s an extensive biographical section on palaeontologists and I think she might have written that.

Caption: I have mostly fond memories of putting the various spreads together. I had all kinds of ideas on which specific animals and pieces of information should be covered, but we were often constrained based on the images we could get.

Dorling Kindersley are a great company to work with and I’ve always enjoyed my projects with them, but this job was intense, there being several teams working concurrently on the different batches. I was soon swamped and drowning in requests and deadlines. Whatever, I developed excellent working relationships with the senior editors (Kitty Blount and Maggie Crowley), the various other editors (Kathleen Bada, Rosalyn Thiro, Giles Sparrow and others), art editor Tim Brown, and others. Giles and I still speak and have worked together on various more recent projects, most recently on my 2017 book Evolution In Minutes.

The visuals. Oh, the visuals. Dorling Kindersley’s books are of course built around the visuals. The dummy spreads (meaning: spreads where the layout has been arranged but the final text remains to be added) began to come in, featuring the artwork that had been commissioned. I’m not, today, going to badmouth the company responsible for that work, but all I’ll say is that it wasn’t of a standard I was expecting.

Caption: I think it’s fair to say that a fair bit of the CG artwork in this book fails to hit the mark. It is not just technically inaccurate but also tremendously ugly.

The initial offerings – the first I saw featured computer generated renditions of the dinosaurs Pachycephalosaurus, Camptosaurus and Dryosaurus – had a very Barney-like quality. More specifically, they’d been based very heavily – too heavily – on John Sibbick’s illustrations from David Norman’s 1986 The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Those illustrations were extremely dated even when produced in 1986, so seeing them serve as inspiration in 2000 was… concerning. I asked what was going on and made it clear that we had a problem. A noted senior palaeontologist who will remain nameless here had, so I was told, given a big thumbs-up on these, and we were stuck with them. A major part of the project then became my working as advisor on the art as I constantly sent notes, sketches and references in order that the images might be corrected as much as possible. I wasn’t paid extra for this, but I should have been.

Caption: a few of the explanatory sketches I produced to help guide our CG artists. The end results do mostly take account of these suggestions.

When passing on reference material, I began sharing images done by Luis Rey (a regular correspondent of mine at the time). At some point the decision was made to actually bring him on and use his illustrations within the book, and in the final version he’s credited as ‘Palaeontological Artist’. Luis’s concept sketches were so good that they feature on the intro pages of the book’s main sections.

Caption: Luis Rey’s sketches - produced to help guide the CG artists - were so good that we ended up using them throughout the book.

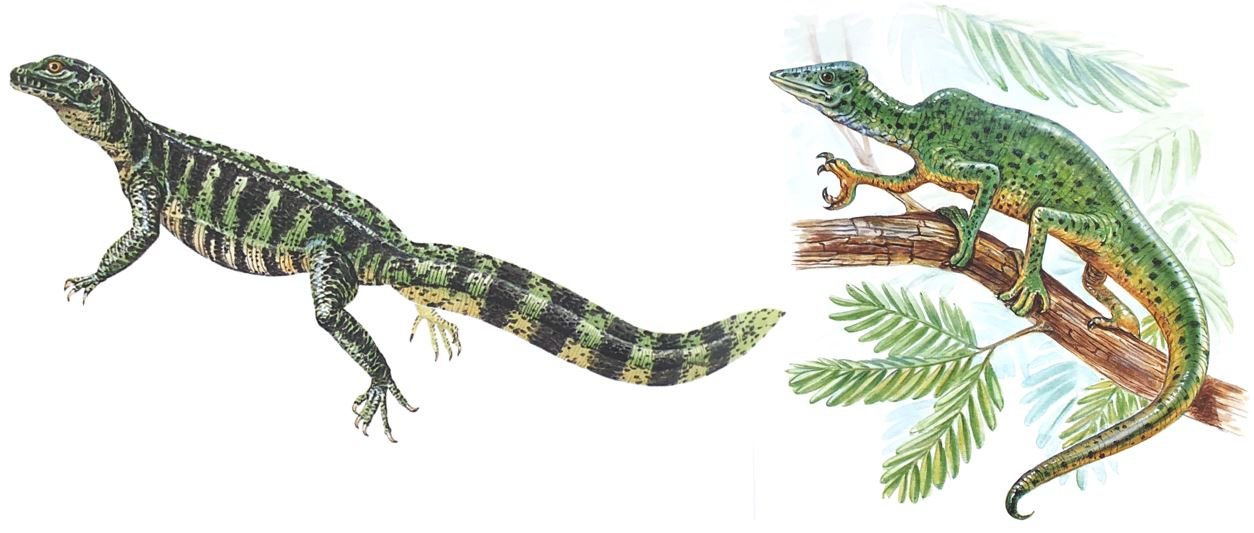

It proved impossible to obtain images for certain obscure animals, among them drepanosaurs, assorted ‘condylarths’ and fossil metatherians. The good news is that we got the people at Wildlife Art (like Robin Carter), Malcolm McGreggor and a few others to produce novel art in conventional media. They’re among my favourite images in the book.

Caption: a selection of art (produced using traditional media rather than via CG) that also features in the book. Clockwise from top left: the metatherian Argyrolagus, the giraffid Giraffokeryx, and the diapsid reptiles Megalancosaurus and Hovasaurus.

Those iconic dinosaur models. I had no involvement whatsoever with the construction of the several dinosaur models that feature in the book, the most famous of which is the green Giganotosaurus that graces the cover. I think it was constructed by Jonathan Hateley and was (I think) specially commissioned. A close-up of the model’s face appears on the cover of the UK edition (and on some other editions too) and a direct result of its familiarity is that it’s partly been the go-to look for Giganotosaurus ever since: green, with assorted nodules and dorsal spikes. I’m not the first to note that it may well be directly responsible for the look of the Giganotosaurus that features in the Jurassic World: Dominion prologue.

Also memorable is the excellent Suchomimus that appears in the book too. A thing of beauty, even if it is doubtful that baryonychines had ‘beaky’ jaws as depicted. The model is also a Jonathan Hateley construction. And then there’s the very blue and very red Caudipteryx.

Caption: the DK Giganotosaurus model in its current home on the Isle of Wight. It’s often in direct sunlight which is not good when it comes to longevity. Image: Darren Naish.

What has become of these models today? The Giganotosaurus used to be on display in Dorling Kindersley’s reception but is today held by Dinosaur Isle Museum on the Isle of Wight, as is the Caudipteryx (which is on display in the main visitor area; the Giganotosaurus is stored in a room used for teaching). Meanwhile, the Suchomimus is currently for sale on ebay! It’s slightly out of my budget (speaking as a pathological collector of model dinosaurs and other animals) but I’ll humbly accept it as a gift should anyone wish to obtain it on my behalf.

Caption: yes, you can obtain the original DK Suchomimus model. Buuut… it ain’t exactly cheap.

I don’t know as much about these models as I’d like but what I do know is that they’re transparently based on images produced by Luis Rey. They’re closely modelled on his paintings and use colour schemes and integumentary details he devised.

Caption: at left, images courtesy of Luis Rey, and showing the very nice Caudipteryx model as it looked back in 2000. At far right.. here it is today at the Isle of Wight’s Dinosaur Isle Museum, looking a bit shabby and faded but still doing its part in advocating feathered non-bird dinosaurs. Images: DK/Luis Rey; Darren Naish.

AMNH tie-in. Another thing established early on is that the book lent, in part, on its being authenticated by experts at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. I’ve now been involved in several projects where US-based museum experts act as consultants or advisors. Their input tends to be minimal but it’s my experience that they do help in preventing errors and helping things remain on-message. John Maisey provided feedback on the planned breakdown of the book and Jin Meng provided some interesting observations on fossil carnivorans.

Caption: compiling simplified cladograms – where you depict key taxa and traits and explain why those traits are ‘important’ – is not easy, and it sometimes took several drafts to produce versions that we were happy with.

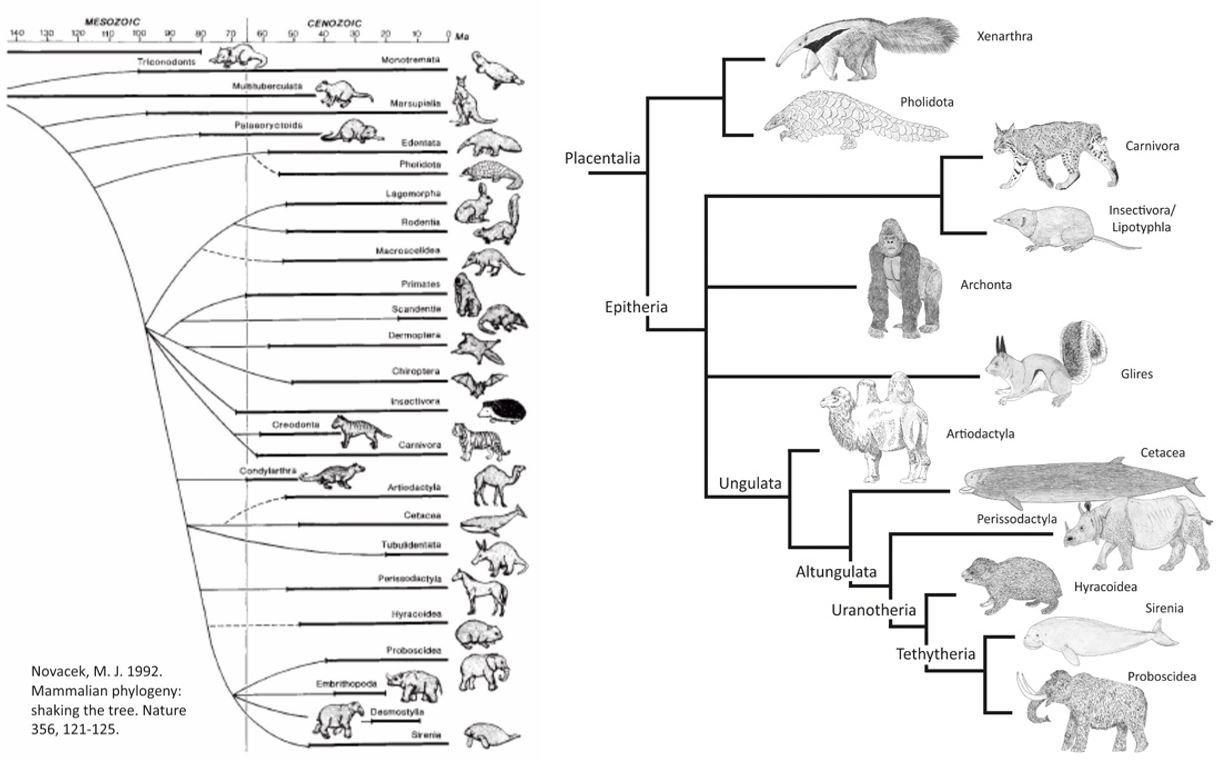

I also found the AMNH connection useful because it meant that I didn’t have to worry about which of the several competing phylogenetic hypotheses I should favour when compiling the cladogram spreads: I could be lazy and simply use whatever was preferred by AMNH-based researchers. Indeed, I’d been sent copies of the AMNH guidebooks penned by Lowell Dingus, Gene Gaffney, John Maisey and others (Dingus et al. 1994, 1995). It explains why the phylogenetic arrangement of the mammals follows the ‘Novacek tree’ (referring to the hypothesis of placental mammal evolution proposed by Mike Novacek; Novacek 1992). DNA-based phylogenies – appearing in the literature at about the same time as I was compiling things – of course meant that the morphology-based Novacek tree was looking increasingly shaky in 2000/2001.

Caption: in devising a cladogram for mammals, it seemed only right to follow Novacek’s (1992) tree, even though new contradictory studies were coming in thick and fast. At right, a very simplified version of the tree, as used previously at TetZoo (see links below).

The final product. Blood, sweat and tears were shed, but we got there in the end. On completion of everything (early April 2001), we had a party somewhere close to the DK office (possibly in a DK office, I no longer remember), something that’s not at all typical. I also recall going for a meal with David Lambert and certain of the editors. A big deal for me, since David’s books had a big influence on me when I was a kid, and I was pleased to tell him this in person.

And so Dorling Kindersley’s Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Life – authored by David Lambert, Darren Naish and Liz Wyse – went to print, my several contractually obliged hardcopies arriving in September 2001. A large, weighty, gorgeously printed book. Translated editions produced for other countries appeared soon after, and yes I did receive them as they appeared (publishers are supposed to send translated versions of a work to the author, but they ordinarily mostly do not). Over the years I’ve mostly sold these, in part because of the space they were taking up. Most translated editions retain the cover design of the UK original but the US version has an inferior ‘encyclopedia-looking’ one featuring a montage of images arranged around horizontal bars. The largest object on that version of the cover is another excellent DK model, namely the Styracosaurus. I’ve just discovered – to my surprise – that a US edition isn’t in my library here, but the Italian edition is, and it features the same cover.

Caption: I don’t own all translated versions of Lambert et al. (2001), but here’s what I have today. For whatever reason, this book’s cover is hard to photograph. The Italian one is titled Enciclopedia dei Dinosauri e Altri Animali Preistorici.

Events afterwards. The book itself won several awards, and reviews that I recall seeing when it was new were overwhelmingly positive. Plus points for a more specialised audience include coverage of quite a few obscure animal groups and the well-designed cladograms. As I said at the start of this article, it’s become obvious to me in recent months that many people who are young or youngish adults today were inspired by this book during their younger years, and it’s generally remembered fondly.

Caption: various of the Dorling Kindersley books I’ve been involved in since 2001, arranged in chronological order (newest at right). I think it’s fair to say that my getting involved with the Encyclopedia in 2000/2001 really paid off in terms of future work. Image: Darren Naish.

The book is also familiar enough and was sufficiently widely distributed that it has virtually been considered ‘the’ standard popular encyclopedia of prehistoric life for a good swathe of people. This fact was brought home to me recently when I learnt (thanks to my friend C. M. Kösemen) about its appearance in season 6 of The Sopranos. I watched The Sopranos when it was on first time round but don’t recall this. I would surely have made a big deal about it at the time had I known about this special appearance.

Caption: Lambert et al. (2001) appears in season 6, ep 4 (‘The Fleshy Part of the Thigh’) of The Sopranos, broadcast in April 2006.

That about wraps up everything I wanted to say. I went on to work with Dorling Kindersley on numerous subsequent occasions, both on similar grand encyclopedia-type works and on smaller, dinosaur-focused books. I don’t have much reason to use the book today – its problematic visuals mean that I’ve never showcased it to publishers or artists when discussing prehistoric life – but I do look back on its creation as formative to my experience as a writer and consultant. The good news on the problematic visuals is that I later worked with Dorling Kindersley in phasing them out and getting them replaced by superior alternatives. This was a years-long process and anyone familiar with Dorling Kindersley’s prehistoric life books can – should they wish – chart things as they happened. The images in their newer books have a very different look, and you have me to thank for that.

Caption: it should be extremely obvious that Dorling Kindersley has really upped its game on the quality of its imagery in recent years. The reconstructions here are from Dinosaurs: A Children’s Encyclopedia of 2011 (and republished several times since) and Knowledge Encyclopedia Dinosaur! of 2014, and I was consultant for both.

The book can still be purchased, at a very reasonable price.

For previous articles relevant to the issues covered or touched on here, see…

It would appear that my other new book is out: Dorling Kindersley's Prehistoric, October 2009

The Refined, Fine-Tuned Placental Mammal Family Tree, July 2015

Books That Influenced Me The Most, April 2017

Tetrapod Zoology Is A Teenager Now, January 2019

Refs - -

Dingus, L., Gaffney, E. S., Norell, M. A. & Sampson, S. D. 1995. The Halls of Dinosaurs. A Guide to Saurischians and Ornithischians. American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Dingus, L., Tedford, R., Gaffney, E., McKenna, M., Novacek, M. & Delson, E. 1994. Mammals and Their Extinct Relatives. A Guide to the Lila Acheson Wallace Wing. American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. 2000. Walking With Dinosaurs: The Evidence. BBC Worldwide, London.

Novacek, M. J. 1992. Mammalian phylogeny: shaking the tree. Nature 356, 121-125.