Ever keen to cover more of squamate diversity – Squamata = snakes and lizards – we here look at a really interesting group of mostly Mexican lizards. They’ve led us on a merry chase with respect to their diversity, taxonomy, phylogeny and historical biogeography…

Caption: some Abronia species are strikingly coloured, as is obvious from these images. Both show Green, Mexican, Sierra de Tehuacan, or Terrestrial arboreal alligator lizards – yes, a name that’s internally contradictory – A. graminea. This species occurs in Veracruz, Puebla and Oaxaca in eastern and southern Mexico. Images: María Eugenia Mendiola González, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here); Ismael EPM, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

One of the several major branches on the lizard family tree is Anguimorpha, the big group that includes the fantastic monitor lizards and the spectacular gila monsters and kin. The ‘core’ group of Anguimorpha is Anguidae, the family that includes slow-worms, glass lizards and alligator lizards (and, maybe, no longer galliwasps… more on that point later).

Caption: I’ve mentioned in previous squamate-themed articles that the art of Alan Male was highly influential to my nascent interest in squamates and herpetology in general. Here are Male’s anguid illustrations, as featured in Philip Whitfield’s Reptiles and Amphibians: An Authoritative and Illustrated Guide of 1983. Galliwasps (diploglossines) have conventionally been included within Anguidae but this is now controversial, since several recent phylogenetic studies have excluded them from this group. Ophisaurus and Anguis are conventionally regarded as close relatives within the anguid clade Anguinae, but some studies find Ophisaurus to be paraphyletic with respect to Anguis. UPDATE: I’d missed that this is no longer an issue given that the sheltopusik is now Pseudopus. See comments! Images: Alan Male, from Whitfield (1983).

And, in turn, the ‘core’ anguid is Anguis, the slow worms. These are superficially snake-like, limbless anguids of Eurasia and north Africa (the Western Palaearctic), and my familiarity with the European slow worm Anguis fragilis in particular means that I’ve written about them a fair bit at Tet Zoo over the years. Slow worms and their close relatives are sorta typical of Western Palaearctic reptiles in that they’re not colourful or striking in appearance, and their biology and natural history is (comparatively) well known and substantially recorded in the literature.

Caption: in recent years, I’ve photographed every Anguis I’ve encountered. Here are a few. This is the only anguid I’ve seen in the wild, and indeed the only one we have here on the Atlantic fringes of western Europe, a place of such depauperate herpetofauna. See the links below for more on this animal. Images: Darren Naish.

But anguids aren’t just animals of the Palaearctic. They occur throughout the subtropics and tropics too, and in fact this is where the bulk of species occur… as ever, our reliance on Palaearctic forms as anchors in nomenclature and natural history knowledge is a quirk of our Eurocentrically-biased scientific history, sorry rest of humanity. Tropical anguids often are colourful and striking, and – in contrast to northerners like Anguis – their natural history and biology is typically poorly known and poorly documented.

In this article (another one rescued from the archives, and now updated and modified), we look at a very beautiful, sometimes bright green, group of mostly arboreal, mostly high-altitude anguids from Mexico and Central America: the Abronia species, sometimes dubbed arboreal alligator lizards. They’re pretty special animals, and – as ever – we don’t know as much about them as we might like.

Caption: Monte Cristo arboreal alligator lizard Abronia montecristoi, a poorly known, endangered cloud forest species from El Salvador and Honduras. It’s mostly brownish; parts of its body were described as ‘cinnamon’ by its describers. Image: Josiah Townsend, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

A brief scientific history. Abronia has been known to science since 1828 when Deppe’s arboreal alligator lizard A. deppii (also called the Guerreran arboreal alligator lizard) was reported from Mexico by German zoologist Arend F. A. Wiegmann (1802-1841), though Wiegmann misidentified this species as part of the alligator lizard genus Gerrhonotus. ‘Deppe’ is German explorer, artist and naturalist Ferdinand Deppe (1795-1861) who collected the specimen on one of his several Mexican expeditions of the late 1820s. In 1838, British zoologist John Edward Gray (1800-1875) realized that Deppe’s species was unusual enough for its own genus and hence the name Abronia was published. Gray coined innumerable generic names across his long career but tended not to explain the etymologies behind them, and even today many have mysterious or unresolved origins. In the case of Abronia, it’s thought that he was commemorating the ‘delicate’ nature of the tail, since that’s what ‘abros’ means in Greek. ‘Delicate’ in this context was presumably a reference to its length and slenderness.

Caption: Abronia deppii photographed in the wild in 2018. These images were uploaded to iNaturalist and an important point worth making here is that records of endangered species – especially of attractive reptiles that are popular in the exotic animal trade – need to have their locality data protected, since there’s a history of unethical collectors visiting specific places to collect live animals. Image: (c) Eusebio Roldán Félix, CC BY-NC (originals here).

During the 1860s, 70s and 80s, new Abronia species were described from additional locations in southern Mexico in addition to Guatemala, Costa Rica and Panama. These showed both that these lizards were moderately speciose – ten had been named by the end of the 19th century – and present across essentially the whole length of Central America. Since then, additional species have come in on a fairly regular basis (the species count right now is 41) and they’ve turned out to include more than half of all species within Gerrhonotinae, the alligator lizard clade. This fact seemingly establishes Mexico and Central America as the pulsating hub of gerrhonotine evolution and diversity, with the USA being a ‘fringe’ area inhabited by immigrants that have moved north. But read on…

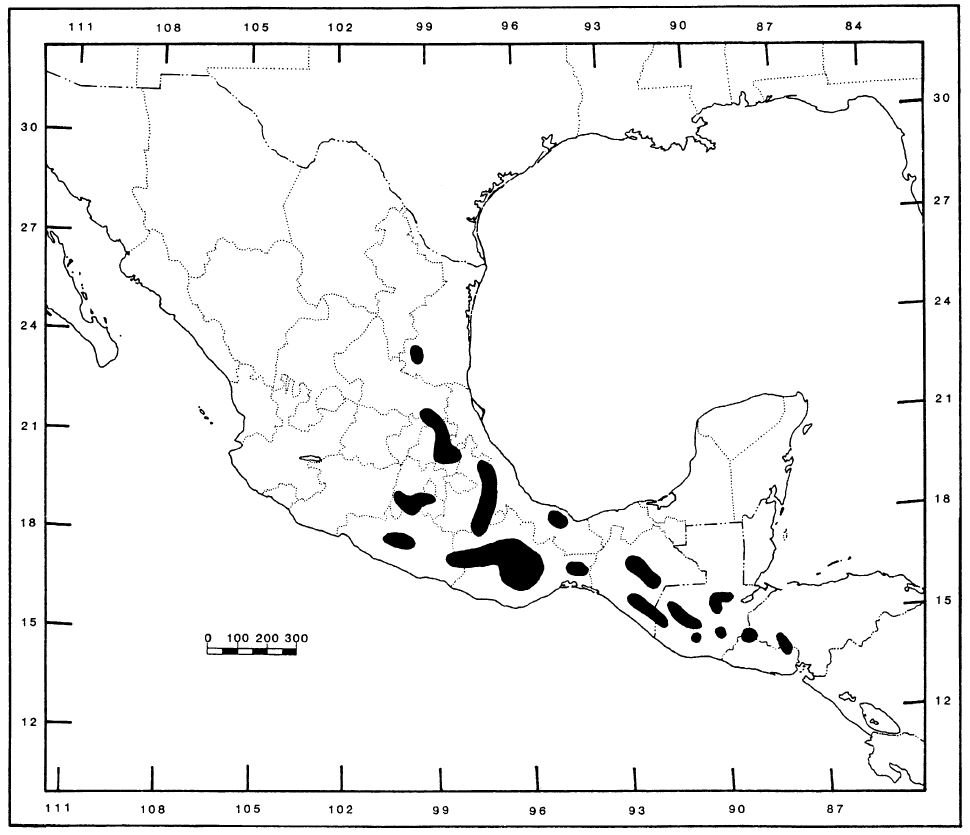

Caption: the distribution of Abronia as depicted by Campbell & Smith (1993). Since 1993, additional records demonstrate the presence of Abronia in additional locations in the far west of Honduras. In addition, the inclusion of Mesaspis within Abronia (see main text) means that the group is also present in northern Nicaragua, through part of inland Costa Rica, and in northern Panama.

Goodbye Mesaspis! During the 1990s, an effort to better understand the evolutionary history of these lizards resulted in a taxonomy whereby the more than 20 species known at the time were grouped into six subgenera, namely Abaculabronia, Abronia, Aenigmabronia, Auriculabronia, Lissabronia and Scopaeabronia (Campbell & Frost 1993). The Central American alligator lizards (Mesaspis), which are smaller, browner, more terrestrial and generally less impressive in appearance than typical Abronia species, were mostly regarded as the Abronia sister-group.

Caption: Morelet’s alligator lizard Abronia moreletii, but formerly Mesaspis moreletii, photographed in Guatemala. Obviously, the species formerly included in Mesaspis look quite distinct from the most familiar members of Abronia (like bright green, rugose A. graminea), so it’s not surprising that they were previously considered generically distinct. Image: Todd Pierson, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

However, molecular results published in 2013 and more recently have shown – a bit surprisingly – that Mesaspis and Abronia are both non-monophyletic (Pyron et al. 2013), and that taxa previously grouped in Mesaspis are scattered about the Abronia tree, grouping specifically with clades of locally occurring Abronia species (Gutiérrez-Rodríguez et al. 2020). A full discussion of what this means and what its implications are is beyond the scope of this article (as ever, I started compiling this intending it to be a very brief review), but the outcome is that the former Mesaspis species are currently subsumed into Abronia, and Mesaspis is no longer in use. Additionally, certain of those supposed Abronia subgenera are not clades (Gutiérrez-Rodríguez et al. 2020).

Caption: the Green, Mexican or Terrestrial arboreal alligator lizard A. graminea is now quite frequently encountered in the pet trade. Its popularity is not surprising in view of how amazing it looks: a local pet reptile establishment near me even has a giant photo of one on their front door. However, it’s endangered and on the IUCN Red List, and collecting for the trade has been one of the contributory factors. Seems pretty wild that you can own an endangered species as a pet…. Image: Ethan Kocak, used with permission.

Appearance and anatomy. Abronia species are often striking in appearance. Like other gerrhonotines, they usually have prominent, rugose dorsal scales on top of similarly rugose osteoderms (the osteoderms are the bony plates beneath the skin; some species have a strongly reduced osteoderm compliment), and a broad and flattened head. Some (like A. aurita and A. anzuetoi, both from Guatemala) possess short spikes around the ears. The limbs of Abronia species are ‘normal’ in proportion, as expected for animals that regularly climb, and not proportionally small as they are in other gerrhonotines. The tail is prehensile, but like other anguids they’re still able to autotomize it if necessary, with regenerated tails being shorter and less functionally effective.

Caption: anatomical illustrations of the heads of various Abronia species, in dorsal and left lateral views, from Campbell & Smith (1993). Note how variable they are with respect to depth of the head, the rear part in particular, and in the distribution, size and number of spike-like scales dorsal to the ear opening. Three of the species here were described and named by Campbell & Smith (1993).

They’re mostly green. Some are bluish or turquoise, some are brown or red, and some have areas of yellow, orange or black on their bodies. Adding further difficulty to efforts to generalize, captive individuals of some species have been observed to change colour over a period of a few months. In some species the pigmentation forms patterns recalling patches of lichen or moss. All Abronia species are viviparous, with some giving birth to a single young, while others produce litters of up to 12 babies. Some authors describe Abronia as ovoviviparous, this being a kind of viviparity where the babies don’t emerge from shelled eggs but aren’t nourished by a placenta. Authors are still frustratingly lazy on the terminological distinction here, and I’m not sure which way we should go (I disagree with the idea that ‘viviparity’ requires the presence of a placenta).

Caption: captive A. graminea providing good views of the rugose dorsal scales and vivid green colour. Abronia is like many anguids in possessing a distinct ‘lateral fold’ that runs along the lower part of the body and separates the scales of the flank from those of the belly. The fold in Abronia is weakly developed compared to that of some other anguids, and its extent on the neck varies across species. Image: Ethan Kocak, used with permission.

Natural history notes. Field data shows that many Abronia species spend most of their lives among epiphytes, and they take shelter in bromeliads and tree holes. Some species live in tree-tops 40 m above the ground, whereas others are encountered beneath logs and rocks on the forest floor. Bogert & Porter (1967) noted that, where arboreal Abronia species occur in Oaxaca, Mexico, the sympatric Barisia and Gerrhonotus are strictly terrestrial while, in Arizona and California (where there are no Abronia species), Gerrhonotus can be found in trees. That might suggest competitive exclusion and maybe ecological competition between these taxa. Unexpectedly, an individual of A. fimbriata in Guatemala was reported swimming in a stream and repeatedly diving to the bottom. This is a reminder of the adage that animals do what they damn well please… or, anatomy is not destiny, take your pick.

Caption: representatives of two other gerrhonotine anguid genera that live in sympatry with Abronia in some places. At top: Barisia, specifically Chihuahuan alligator lizard B. levicollis photographed in Chihuahua, Mexico. At bottom: Gerrhonotus, specifically Pygmy alligator lizard G. parvus photographed in Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, Mexico. Images: Marisa Ishimatsu, from Lemos-Espinal et al. (2017), CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here); Michael Price, CC BY-NC-ND (original here).

As ever with unusual tropical squamates, it’s hard to recommend a single go-to literary source on this group. The most useful and comprehensive review is a 1993 paper by Campbell & Frost (1993). 23 species were known to them at the time of their review, and they grouped these into six subgenera, namely Abaculabronia, Abronia, Aenigmabronia, Auriculabronia, Lissabronia and Scopaeabronia. They noted their awareness of several additional species that were awaiting publication, and it was clear that diversity within the group was set to increase a fair bit over coming decades. As noted earlier, the number of recognized species right now is 41, recently named species including such Mexican endemics as the Sierra Morena arboreal alligator lizard A. morenica Clause et al., 2020, A. zongolica García-Vázquez et al., 2022 from Veracruz, and the Coapilla arboreal alligator lizard A. cunemica Clause et al., 2024 from Chiapas.

Caption: at left, portrait of Sierra Morena alligator lizard Abronia morenica, a species endemic to southern Mexico’s Sierra Madre de Chiapas, named in 2020. At right, depiction of A. zongolica from the Sierra de Zongolica in Mexico’s south-east, named in 2022. These illustrations do a good job of showing the sculpted surface texture of the scales present across the head, plus much of the body as well. Images: AMANTEDESAURIOS CC BY-SA 4.0 (originals here and here).

Sympatry among Abronia species is unusual and rare, and reported cases have proved controversial and either erroneous, or just about impossible to verify (Campbell & Frost 1993, Townsend Peterson & Nieto-Montes 1996, Pianka & Vitt 2003).

The bad news is that the very localized distribution of many Abronia species makes them vulnerable to extinction, and Campbell & Frost (1993) estimated that perhaps 13 species will become extinct in the next few decades. Indeed, some species are known from just a single specimen, or have gone undocumented for several decades (e.g., A. montecristoi from El Salvador, named in 1983), meaning that we have no information on their current status.

Incidentally, when I published the previous version of this article back in 2007, I listed A. mitchelli from Oaxaca (named in 1982) as among those species known from a single specimen. Since then, a claim has been made that at least one additional individual has been encountered in the wild, leading some authors to list it as ‘rediscovered’ (Lindken et al. 2024). A. ochoterenai from Chiapas, a bright red species named by Rafael Martín del Campo in 1939 but then considered lost, has also recently been rediscovered alive in the wild (Lindken et al. 2024).

Caption: Abronia ochoterenai was named in 1939 by Mexican herpetologist Rafael Martín del Campo y Sánchez, initially as a subspecies of an anguid regarded at the time as a Gerrhonotus alligator lizard (this was G. vasconcelosii, which was itself transferred to Abronia later on). Unfortunately, del Campo only gave the type locality as "Santa Rosa, Comitan", Chiapas, Mexico and at least 16 villages in the region have this name. Substantial discussion has surrounded where additional specimens might be found, and things were confused and unresolved until recently. As reported by the HERP.MX team in 2019, additional specimens have now been discovered, specifically at an unnamed sierra on the Atlantic slopes of southeastern Chiapas. As you can see, it’s a spectacular animal. Image: HERP.MX.

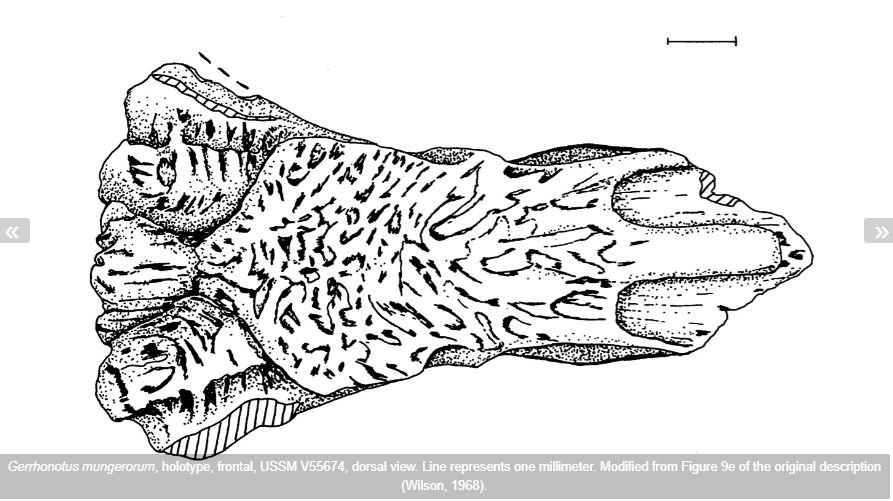

Complications provided by fossils. Back when I first wrote about Abronia (the aforementioned 2007), the genus didn’t have a fossil record. It was appropriate, however, to note that a few fossils appeared close to it and might ultimately prove relevant to its ancestry. Gauthier (1982) and Estes (1983) noted that Gerrhonotus mungerorum from the Miocene and Pliocene of Nebraska and Kansas – known only from its frontal bone and sometimes called Munger’s alligator lizard – resembles Abronia and might be close to it (though they also noted that it resembles the Mexican gerrhonotine Barisia). And then there’s Paragerrhonotus ricardensis, supposedly the closest relative of Abronia, from California (with some questionable specimens from Nebraska).

Caption: the Gerrhonotus mungerorum holotype frontal (anterior to the right; scale bar = 1 mm) as figured by J. Alan Holman in 1975, but here taken from the Kansas Herpetofaunal Atlas. What herpetologists have conventionally called ‘the frontal’ in squamates is actually the two frontal bones fused into a single unit, but people are nothing if not inconsistent across research groups.

If these fossils are indeed close to Abronia, maybe they demonstrate that it originated in the USA before moving southwards during the Pliocene, perhaps as a result of cooling conditions. Relevant here is that old cautionary tale about neglecting fossil species when looking at problems of this sort. Macey et al. (1999) produced a biogeographical analysis of gerrhonotines based on extant taxa and – because ‘Mesaspis’, Abronia, Gerrhonotus and Barisia all have distributions centred around Mexico, Texas and Central America – their area cladogram makes it look as if Mexico (or thereabouts) was the place of origin for this clade. Throw in the fossils though, and doubt arises.

Post-2007, we have a definitive fossil Abronia, a very nice skull from the Miocene Caliente Formation of California (and thus about 11 or 12 million years old), named A. cuyama by Scarpetta & Ledesma (2023). The specimen was collected in the Cuyama Valley Badlands in southern California back in the 1950s but misidentified as a Gerrhonotus. It’s part of an assemblage of small animal fossils that appear to represent an accumulation of owl pellets. Owls, we’ve learnt, are the friends of the vertebrate palaeontologist, species worldwide having contributed massively to our knowledge of small animals. Subjected to CT-scanning and described in detail, the A. cuyama skull has the wide frontal and heavily sculpted osteoderms, with a ‘vermiculate’ ornamentation, unique to Abronia, and it has osteoderm characters unique to itself and not present in any other Abronia species.

Caption: at left, the Abronia cuyama fossil (in both colour and black and white; in right lateral, left lateral, and dorsal views), a partial skull with intact cranial osteoderms. At right, map from Scarpetta & Ledesma (2023) showing how distant the collection locality of A. cuyama is from the modern range of Abronia. Does this mean that Abronia previously occurred right across the south-western USA and northern and western parts of Mexico? Images: Scarpetta & Ledesma (2023).

What does its presence in California mean for the prehistoric distribution and origin of this group? That’s not entirely clear, mostly because – surprisingly – the specimen was found to be deeply nested within Abronia when included within a phylogenetic analysis. It’s not an outgroup to the rest of Abronia, and thus can’t be used as evidence for more northerly origins. Instead, maybe it shows that Abronia was ancestrally present throughout southern California and, presumably, across the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico’s north before becoming extinct in both regions. If that’s true, habitats like those inhabited by Abronia today were presumably more widespread during the later parts of the Miocene. Another possibility is that A. cuyama represents a singular expansion of the group northwards. We can’t really say in the absence of additional fossils. The fact that an owl transported the specimen could mean that the animal wasn’t local when alive, but this appears contradicted by the idea that the sort of owl responsible for the pellets was most likely a ground-hunting, relatively sedentary species (Scarpetta & Ledesma 2023).

Caption: so that’s another squamate-themed article from the Tet Zoo archives updated and rescued. This one originally appeared at Tet Zoo ver 2 (the ScienceBlogs years) in 2007. As you can see from these screengrabs, the illustrations originally included were very different and I previously included a short diversion on phylogeneticist Jacques Gauthier, his squamate-themed research, and the books visible in the background of the photo I’d featured. I couldn’t do that this time around as I couldn’t find a version of the photo that’s of sufficient resolution.

Goodbye, Abronia. And that about sums up everything I wanted to say. Anguids, and anguimorphs as a whole, are among the most charismatic and popular of lizards and there’s lots more about them I need to publish… my galliwasp writings, promised since about 2007, are now waaay overdue. Abronia specifically is now a bit of a superstar and also, increasingly, a flagship genus in terms of conservation interest, so I’m pleased to have covered it again. These lizards are beautiful and fascinating, still so mysterious and enigmatic, and perpetually at risk from the destruction and deterioration of their habitat.

For previous Tet Zoo posts on other squamates see…

In Quest of Anguids, May 2006

Pompey and Steepo, the World-Record-Holding Champion Slow-Worms, May 2007

Cambodia: now with dibamids!, May 2011

The Tet Zoo Guide to Mastigures, August 2018

The Remarkable Basilisks, May 2023

Do Lizards Really Have ‘Mite Pockets’?, March 2024

Meeting Lake Zacapu’s Garter Snake, March 2024

Ray Hoser, Number 1 Taxonomic Vandal, May 2024

The Mysterious Dibamids, May 2024

The Rehabilitation of Günther’s Black Cameroonian Snake, May 2024

Ikaheka and Other ‘Palatine Draggers’, Cryptozoic Elapid Snakes of Melanesia, June 2024

Refs - -

Bogert, C. M., & Porter, A. P. 1967. A new species of Abronia (Sauria, Anguidae) from the Sierra Madre del Sur of Oaxaca, Mexico. American Museum Novitates 2279, 1-21.

Campbell, J. A. & Frost, D. R. 1993. Anguid lizards of the genus Abronia: revisionary notes, descriptions of four new species, a phylogenetic analysis, and key. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 216, 1-121.

Estes, R. 1983. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie. Part 10A. Sauria Terrestria, Amphisbaenia. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart, New York.

Gauthier, J. A. 1982. Fossil xenosaurid and anguid lizards from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation, southeast Wyoming, and a revision of the Anguioidea. Contribution to Geology of the University of Wyoming 21, 7-54.

Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, J., Zaldívar-Riverón, A., Solano-Zavaleta, I., Campbell, J. A., Nelsi Meza-Lázaro, R., Flores-Villela, O., Nieto-Montes de Oca, A. 2021. Phylogenomics of the Mesoamerican alligator-lizard genera Abronia and Mesaspis (Anguidae: Gerrhonotinae) reveals multiple independent clades of arboreal and terrestrial species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 154, 106973.

Lindken T., Anderson, C. V., Ariano-Sánchez, D., Barki, G., Biggs, C., Bowles, P., Chaitanya, R., Cronin, D. T., Jähnig, S. C., Jeschke, J. M., Kennerley, R. J., Lacher, T. E., Luedtke, J. A., Liu, C., Long, B., Mallon, D., Martin, G. M., Meiri, S., Pasachnik, S. A., Reynoso, V. H., Stanford, C. B., Stephenson, P. J., Tolley, K. A., Torres-Carvajal, O., Waldien, D. L., Woinarski, J. C. Z. & Evans, T. 2024. What factors influence the rediscovery of lost tetrapod species? Global Change Biology 30, 1-18.

Macey, J. R., Schulte, J. A., Larson, A. Tuniyev, B. S., Orlov, N. & Papenfuss, T. J. 1999. Molecular phylogenetics, tRNA evolution, and historical biogeography in anguid lizards and related taxonomic families. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 12, 250-272.

Pianka, E. R. & Vitt, L. J. 2003. Lizards: Windows to the Evolution of Diversity. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Scarpetta, S. G. & Ledesma, D. T. 2023. A strikingly ornamented fossil alligator lizard (Squamata: Abronia) from the Miocene of California. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 197, 752-767.

Townsend Peterson, A. & Nieto-Montes, A. 1996. Sympatry in Abronia (Squamata: Anguidae) and the problem of Mario del Toro Aviles’ specimens. Journal of Herpetology 30, 260-262.

Whitfield, P. 1983. Reptiles and Amphibians: An Authoritative and Illustrated Guide. Longman Group Ltd, Harlow, UK.