Listeners of the Tetrapod Zoology podcast will know that I have – for no specific reason – been going through a bit of a Loch Ness Monster phase recently, my stated aim being to review three recently-ish published books on the subject. Here’s the first of those reviews, devoted to Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. I provided a very brief review of this book at TetZoo ver 3 back in 2017 but always planned to produce a longer version. So here we are.

Caption: Nessie, the beast of many forms. It’s almost as if people are describing all manner of different things. Images: Darren Naish.

Is the Loch Ness Monster (LNM) science? Should I be writing about it, and encouraging an interest in it, on a blog ostensibly devoted to the scientific study of the natural world? Here I’ll say what I’ve said several times before about monsters and cryptozoology in general: even if monsters don’t exist (in the zoological sense), there’s still a phenomenon here that’s worthy of study, and there’s still a body of data that we can subject to scientific analysis. And I’ll add that ideas and writings about monsters like Nessie are definitely relevant to those of us intrigued by speculative zoology (Naish 2014), fringe theories, the history of zoology and other subjects included within the TetZoo remit.

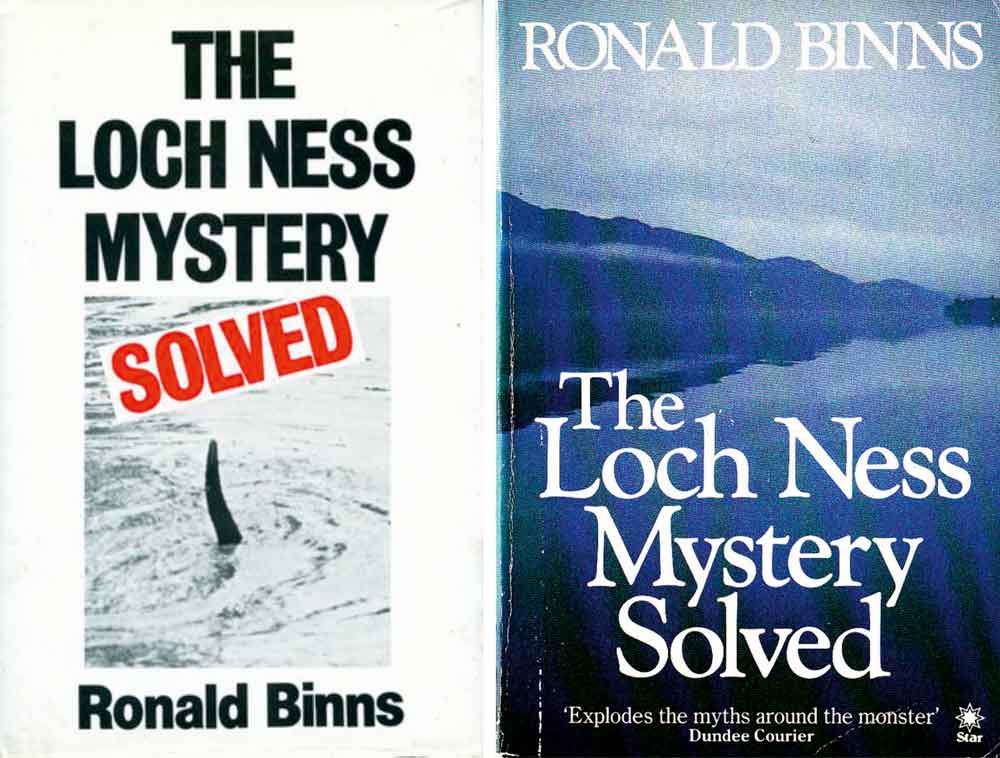

Caption: Binns (1983), hardback (at left) and 1984 softback edition.

Ronald Binns’s 1983 The Loch Ness Mystery Solved – produced with assistance from Rod Bell (though he doesn’t get an authorship credit) – is a classic work of scholarship and scepticism (Binns 1983). It shows how sightings, photos and film purporting to describe or show the monster are less impressive than typically described, are indeterminate or of more prosaic identity than claimed, have been embellished or modified by enthusiastic or biased writers, and can sometimes be explained as encounters with known animals (seals, waterbirds, deer). A sociocultural setting for the monster, an evaluation of the clutching-at-straws ideas on its biology, appearance, phylogenetic affinities and ecology, and a takedown of the ‘historical Nessie’ endorsed elsewhere also feature within the book (Binns 1983).

Caption: it should not be assumed that people - even people who’ve lived their lives in rural places, surrounded by wildlife - can always identify such animals as deer, seals and waterbirds (like grebes and cormorants) when they see them in unusual places, poses or situations. Deer are abundant around Loch Ness. I photographed this male Red deer adjacent to Loch Knockie, which is just a few hundred metres to the east of Loch Ness. Image: Darren Naish.

I’m glad to have encountered it at a relatively early phase in my career as a monster researcher, since virtually everything else I read and was exposed to was extremely pro-monster, so much so that I spent time as a teenager thinking that Nessie was a scientific likelihood. Phew: lucky, then, that I never made a fool of myself by proclaiming a belief in Nessie. Oh, wait.

Of course, much has happened since the publication of Solved in 1983. We have new biographic information on the people integral to the LNM story, and new eyewitness accounts, illustrations and photos have been unearthed or have joined the collective pool. Several of the main characters in the LNM story have died since Solved was published, meaning that their role can be more fully and honestly assessed than when they were alive (Binns 2017). On the sociological angle, Nessie has remained a cultural icon and flashpoint for woo, and its story has been retold, embellished, added to and expanded via the publication of many post-1983 books, so many that there’s what looks like a (mostly British) cottage industry on the subject.

Caption: cover of Binns (2017). Buy it if interested in the Loch Ness Monster, lake monster lore, cryptozoology or scepticism.

In view of all this, the time is right for an addendum to Solved, and thus we find The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded (Binns 2017). Reloaded is, to quote its author, essentially a long-form appendix to The Loch Ness Mystery Solved, but it isn’t at all dry or tedious. It’s well written, entertaining and absorbing if you’re familiar with any aspects of LNM lore, and in fact is probably the LNM-themed book I’ve enjoyed reading the most. Footnotes and references are provided, though there are only a handful of illustrations.

The book begins with a look back at the making of Solved, the responses to it, and a series of updates on the book’s main (human) characters. Binns then retreads two classic sightings – that of Donaldina Mackay and the Spicers – albeit with new information. The Spicer account of 1933 is the great classic ‘land sighting’, recounted in every Nessie-themed book. George Spicer is generally framed as a lucky everyman who saw a remarkable, inexplicable thing and reported it fairly, without fanfare and without any need to see himself – rather than the animal – as the point of interest.

Caption: the Spicer sighting as conventionally portrayed, here by Dinsdale (1976). Image: Dinsdale (1976).

None of this is correct. Details of Spicer’s account make it likely that he and his (still nameless) wife saw bounding deer (an idea, not original to me, discussed in Hunting Monsters); the details of his sighting changed significantly over the years and demonstrate (I say again: demonstrate) both embellishment and a predilection on Spicer’s part to speculate. Furthermore, Spicer wasn’t a quiet, impartial witness, reluctantly discussing his encounter when door-stepped by thirsty journalists, but extraordinarily enthusiastic, garrulous and boastful about it, his own writings making him sound wide-eyed and credulous. There’s a popular idea among cryptozoologists that one should ignore personality traits and biography and just pay attention to the monster sighting. Alas, no; this is wrong. Those things are absolutely relevant.

Caption: probably the best ever depiction of the Loch Ness Monster in action. Surely this is what Mr Spicer actually saw. A beautiful image by the legendary Gino D’Achille. Image: (c) Gino D’Achille.

Famous photos, reloaded. Chapters are also devoted to the more notable LNM photos and the Dinsdale film. Revised and updated takes on the Surgeon’s photo, and on the Gray, Stuart, Cockrell, Macnab and O’Connor photos – and a bunch of less famous ones – are presented, all of which can sensibly be stated to be hoaxes, indeterminate, waves, sticks and other non-animals. Binns remains non-committal on the very unusual Peter O’Connor photo of 1960 but implies that O’Connor’s career as a taxidermist might mean that we’re looking at a dead animal (maybe a seal?). My competing idea (Naish 2017) – it originates with Dick Raynor – is that it’s an inverted kayak and a head-shaped stick in front. I think this explains what looks like planking and the metal rudder support, visible in uncropped versions of the image.

Caption: the O’Connor photo has never made sense as goes lighting. O’Connor’s story is suspiciously odd. And the object he photographed does not appear to be an animal. It looks likely to be an inverted kayak, and looks uncannily similar to the specific kayak that O’Connor owned. The image here - scanned from one of the several LNM books - is a cropped version that doesn’t feature the whole of the object. Image: (c) Peter O’Connor.

Nor does Binns wholly buy my argument in Hunting Monsters than the Hugh Gray photo depicts a swan. He does think it’s a fake though. I remain pretty confident about the swan hypothesis because a Whooper swan (not a Mute swan as implied by the illustration in Hunting Monsters) matches the shape, hue and likely size of the object, the object has what looks like a swan’s ankle sticking out of its flank in the right position, and also has an otherwise inexplicable pale patch (presumably double-exposed on top of the main image, and coming from a moment in time when the bird had its head above the water surface) that exactly matches a Whooper swan’s bill patch. It also has a swan’s tail. And it’s white.

Caption: at top, the Hugh Gray photo of 1933. A ‘mid-sized’ object (look at the ripples), that’s white or near-white, has a sinuous appendage at one end, a short, pointed appendage at the other, and a dark appendage that disappears into the water close to one of its ends. The double-strike areas (featuring pale triangular patches) indicate double-exposure (that is, the film failed to move on and was exposed again). Image: Naish (2017).

On vocal champions. It’s frequently implied or stated by those endorsing the existence of monsters that vocal champions of the cause are sensible, level-headed, scholarly types who come to the conclusions they do after carefully and scientifically evaluating the data. Maybe this is true for some individuals. But it’s generally the opposite of true. Monster proponents – and I’ve now been bold enough to state or imply this in print (Conway et al. 2013, Naish 2017) – are more frequently tremendously naïve, biased, impressionable and unscientific, and attracted to the subject because of its intrinsic appeal and their own tendency to want the world to be occupied by stuff considered beyond current scientific knowledge.

This is emphasised in Binns’s chapters on F. W. ‘Ted’ Holiday, author of 1968’s The Great Orm of Loch Ness (wherein Nessie is posited to be a giant Tullimonstrum) and 1973’s The Dragon and the Disc (the main thesis of which links lake monsters with the ancient alien movement). Similarly, Binns’s treatment of Tim Dinsdale, the well-meaning and likeable champion of the LNM from 1960 until his death in 1987, discusses Dinsdale’s propensity to be all too impressionable, and with ideas that were not in keeping with his claim that he was always objective and basing everything monster-related on sound science. There’s a lot that could be said about both men (I’m avoiding that here; Dinsdale will be discussed in a future article); anyone interested in their legacy and how it fits into the LNM story must see what Binns has to say.

Caption: ahh, classic Holiday. The object in the Hugh Gray photo interpreted as a modern-day, big Tullimonstrum. Image: Holiday (1968).

Both those interested in, and brought to despair by, the literature on the LNM will have noted that there’s a lot of it: an enormous number of published books, booklets and articles, and a vast quantity of correspondence, imagery and art. Yet for all the fame of the LNM, there’s been surprisingly little effort to collate or gather things and several collections are in danger of being lost when their owners are no more and their estates dissolved. Binns terms this the ‘archive problem’, and it’s common to many subject areas that involve ‘paperwork’.

Caption: but a fraction of the books that exist on the Loch Ness Monster. Image: Darren Naish.

As mentioned above, a great many books have been published on the LNM since the early 1980s. Binns provides commentary on the more recent of them (those from the post-Dinsdale era). He's fairly critical of Gareth Williams’s serious and well-drafted A Monstrous Commotion of 2015 (another of the books set to be reviewed here), noting that it fails to credit The Loch Ness Mystery Solved despite drawing substantially upon its contents. Those lines in the acknowledgements of A Monstrous Commotion explaining how eagle-eyed reviewers and editors did a sterling job in preventing numerous mistakes are ironic in view of the fairly enormous number of errors that did make it into print, all of which Binns discusses and corrects (pp. 150-152).

Binns on Hunting Monsters. I am of course especially interested (I hope understandably) in what Binns says about my own Hunting Monsters, a volume he classes as part of the same ‘cultural cryptozoology’ school as Loxton and Prothero’s Abominable Science! (which I had a hand in as technical reviewer and blurb-writer; my review of that book is here at TetZoo ver 3). Hunting Monsters is “fluent, elegant, scholarly”, says Binns (p. 153); he “finds Naish’s approach congenial because he seeks to rescue cryptozoology from the naïve literalists” (p. 154).

Caption: in which I tried to develop a sociological or anthropological view of cryptids - Nessie included - as icons embedded within culture. The softback version was preceded by a 2016 digital one (which has a different cover). Image: Naish (2017).

It isn’t a coincidence that Binns finds my take on monsters concordant with his own position. As has been stated here at TetZoo many times now, I think today that cryptids like Nessie are sociocultural phenomena, that people ‘see’ monsters like Nessie because they fully expect to encounter a thing that’s firmly embedded within their culture (Binns terms this expectant attention), that ideas about the identity, biology, ecology and so on of Nessie are nothing more than speculative house-of-cards-type efforts, and that eyewitness descriptions of Nessie are either so ambiguous as to be useless, are hoaxes, or are explainable or near-explainable by those able to employ critical thinking or sceptical analysis.

Caption: you can be an atheist and still love buildings of worship. Likewise, thinking that Nessie is not real does not stop Loch Ness from being a remarkable place or one with a great amount of allure. Image: Darren Naish.

The Age of the Internet. It’s no secret among those especially interested in the LNM that one of the most visible writers on the subject in the Age of the Internet is not a journalist or scientist but a blogger – Roland Watson – who is unashamed and thoroughly biased in his insistence that Nessie is real and that those questioning the ‘evidence’ are wrong and on ground shakier than the firm footing occupied by himself. Binns notes that Watson has been useful in uncovering new data but more impressive are the substantial number of occasions in which Binns corrects or contests Watson’s interpretations.

Watson’s blog is a fun read if you like being immersed in detailed discussions of LNM-themed sightings, anecdotes, accounts and controversies. I congratulate anyone aiming to put esoteric data like this on the record, and to unearth more information on relevant people and the backgrounds to claimed eyewitness accounts.

But two issues ruin Watson’s entire take on the subject. One is his obvious employment of confirmation bias and insistence that Occam’s Razor has no place in monster hunting: while the record shows that he doesn’t automatically identify any object seen in the waters of Loch Ness as a monster, his primary argument on many occasions is to insist that ‘giant unknown aquatic vertebrate species’ should, as an explanation, be on equal footing with ‘swimming deer’, ‘unidentified fish’ or ‘wave’. No it shouldn’t.

Caption: the surface of Loch Ness, photographed in September 2016. Many people’s monster sightings are of a calibre similar to this. These are waves, made by a boat. Image: Darren Naish.

The second issue is Watson’s obsession with sceptics, who he very much regards as The Bad Guys, The Enemy. He bashes sceptics a lot – as if being sceptical about Nessie is a bad thing or represents poor life choice – and has written at length about the motivations that, he thinks, drive sceptics and their scepticism. These arguments are naïve, way off base and just fucking weird. Example: Watson claimed on his blog and in his review of Hunting Monsters that I have been groomed – his word – by Loch Ness expert Dick Raynor, since sceptics require that the chalice of Loch Ness scepticism be passed down across the generations, and, furthermore, that I have been turned to the cult of scepticism via the nefarious chicanery and allure of an older man. Binns noted all of this as it was happening. “Naish’s assertion that Watson inhabits ‘an idiosyncratic intellectual landscape’ was a generous and measured response”, he says (p. 18). Damn straight.

Those of us sceptical about lake monsters are so, or have become so, because we aren’t convinced by the evidence, such as it is, and we see obvious problems with the ‘data’ deemed integral to the case by believers. I’ve become a sceptic for these reasons, not because I wish to be part of a special club (note to Nessie fans reading this: I am not employed in academia), not because I somehow earn points or money for being a sceptic (I wish), and not because I’m guilty of sloppy thinking, blindness, unfamiliarity with the evidence or an unwillingness to read or engage with the literature or the cryptozoological community. I was a believer once, I remind you, and I’ve said all sorts of silly things supporting the existence of monsters that my critics never seem to be aware of. They only see an enemy: a blinkered ivory-tower elite who lives in a solid gold house, has never had a proper job, and dives every evening into a money pit of Science Dollars provided by the government or something.

Caption: here’s a close-up of the Hugh Gray photo again. I say again: the ripples show that this object is ‘mid-sized’ (as in, 1 m long or so). Weird that an object which I say looks like a swan also has what looks like a swan’s leg and what looks like a swan’s pointed tail.

You should buy this book. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded is required reading for those interested in the Loch Ness phenomenon, in lake monsters, cryptozoology and/or scepticism, and I really enjoyed it. My one complaint is that the lack of an index is a real pain. We all know that indexes are difficult and time consuming to compile, but lacking one entirely is not really excusable – even a short one consisting of keywords is better than nothing.

Anyway… it would be helpful to read Reloaded right after The Loch Ness Mystery Solved if you haven’t read that book already, but I wouldn’t say that this is a requirement. You should definitely buy it. And you should also consider leaving a positive amazon review given a really appalling bias present there at the time of writing. More Nessie book reviews soon.

Binns, R. 2017. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. Zoilus Press. pp. 222. ISBN 978-1-9997359-0-6. Softback, refs. Here at amazon, here at amazon.co.uk.

Nessie and related issues have been covered on TetZoo a fair bit before, though many of the older images now lack ALL of the many images they originated included…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013 (now stripped of all images, so completely useless)

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014 (now stripped of all images)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Refs - -

Binns, R. 1983. The Loch Ness Mystery Solved. Open Books, London.

Binns, R. 2017. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. Zoilus Press.

Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M. & Naish, D. 2013. Cryptozoologicon Volume I. Irregular Books.

Dinsdale, T. 1976. Loch Ness Monster (Revised Edition). Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Holiday, F. W. 1968. The Great Orm of Loch Ness. Faber and Faber, London.

Loxton, D. & Prothero, D. R. 2013. Abominable Science! Columbia University Press, New York.

Naish, D. 2014. Speculative zoology. Fortean Times 316, 52-53.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.