Time for another article from the extensive TetZoo archives, this time a piece from ver 2, 2008 (original here). We begin with this interesting photo provided by my good friend Markus Bühler (of Bestiarium): it shows a bull Asian elephant Elephas maximus at Hagenbeck Zoo, Hamburg…

The picture is neat for a few reasons. For one, it emphasises the agility of elephants: despite their size and ‘graviportal’ specialisations, they can still do some pretty impressive bending and stooping. They’re not bad at climbing slopes, albeit ordinarily ones shallower than the zoo trench shown here. Actually, people have reported (and even illustrated) elephants clambering down precipitous slopes. Tennent (1867) showed an Asian elephant clambering down a slope on its elbows, belly and knees, and quoted a report from 1844 that described this behaviour. The 1844 report even states that this ‘“is done at more than an angle of 45°” (Tennent in Carrington 1958, p. 72).

Caption: James Emerson Tennent’s 1867 depiction of an elephant descending a steep slope, from his book The Wild Elephant.

What also interests me is the shape of the bull’s head. Compare it with this remarkable photo of a bull Asian elephant, taken in Nepal in or around 1994…

Caption: the large elephant Raja Gaj, photographed by Rula Lenska.

You’ll note that he has large twinned domes on the top of his head, and a large bony convexity at the base of his trunk. These aren’t unusual features; they’re typical for big, old males, but they’re unfamiliar to many people because they’re used to seeing females or juveniles of this species. Since 1987, two particularly large bull Asian elephants – Raja Gaj and Kansha – have been observed, photographed and filmed in Bardia National Park, Nepal (Blashford-Snell & Lenska, Lister & Blashford-Snell 1999). Raja Gaj was about 3 m tall at the shoulder. Both animals exhibited particularly massive skull domes and a large nasal convexity, and this unusual appearance led to the speculation that the animals might be living examples of Stegodon. This idea seems to have originated from Clive Coy at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology and was promoted by John Blashford-Snell, who led an expedition to film the Bardia elephants and (with actress Rula Lenska) later wrote a book on them (Blashford-Snell & Lenska 1996).

In fact the Bardia elephants don’t look like Stegodon at all, and when lecturing on the Bardia elephants the picture that Blashford-Snell would show of a Stegodon was not a Stegodon at all, but in fact a reconstruction of the fossil Asian species Elephas hysudricus from Osborn’s 1942 The Proboscidea. Somewhere, things had gotten confused, and the reference to Stegodon isn’t made in Blashford-Snell and Lenska’s 1996 book.

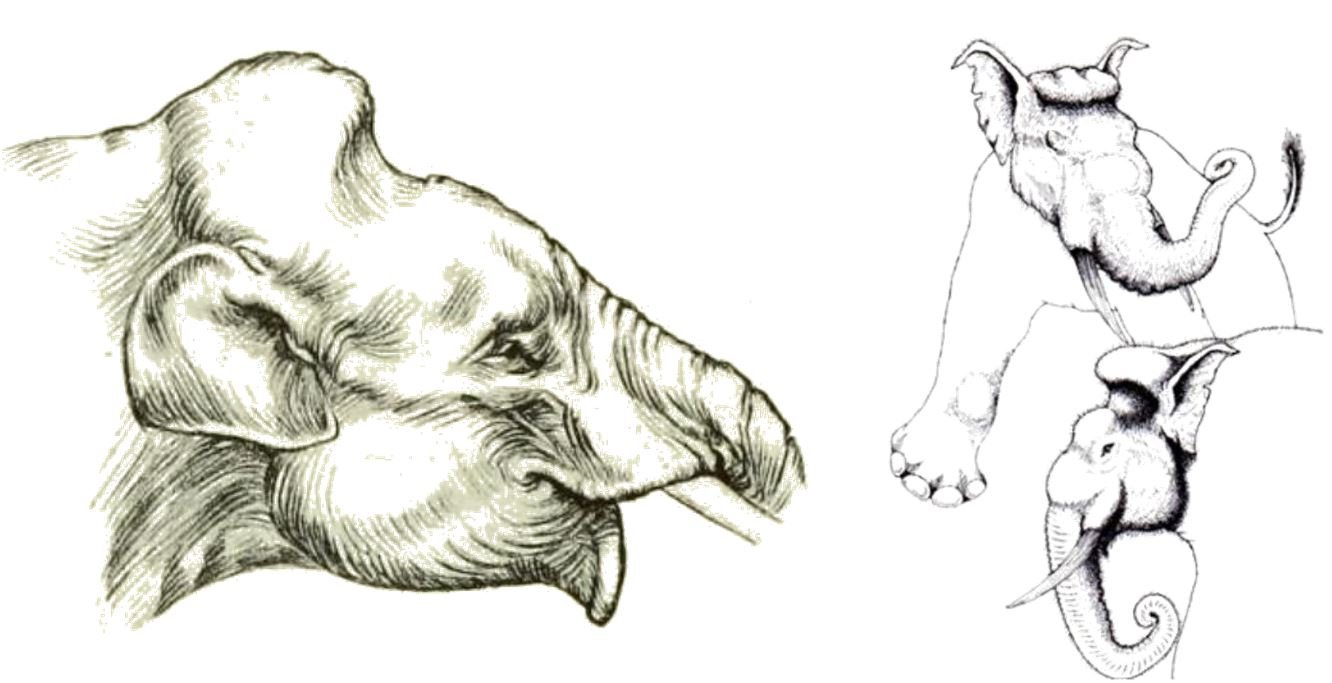

Caption: reconstructions of Elephas hysudricus in life. At left, the image from Osborn (1942), where the animal is labelled Hypselephas hysudricus. The image is by Margaret Flinsch and was based on a skull described by Hugh Falconer in 1845. At right: an even more ‘extreme’ vision of the same species was provided by Deraniyagala (1958).

Lister (1995) noted that the Bardia elephants superficially resembled E. hysudricus, and suggested that bottlenecking had resulted in the emergence of genetic ‘throwbacks’ in the Bardia region. Later DNA results showed that the Bardia elephants were genetically bottlenecked and quite distinct compared to other Asian elephant populations, but they were definitely part of E. maximus (though note that I say all this from stuff I’ve seen on TV: I can’t find it reported in the literature). Indeed, as emphasised by the Hagenbeck Zoo example shown above, the skull morphology of the Bardia elephants wasn’t that unusual anyway, with the Bardia animals falling within the range of variation already known for Asian elephants, albeit at the extreme end of that range. The late Clinton Keeling was to point out that the twinned skull domes of big, old Asian elephant males were termed ‘domes of wisdom’ in Indian folklore.

One last thing: E. hysudricus, the fossil species sometimes compared to the Bardia elephants, is – in being Asian – not necessarily typical of fossil members of its genus, as some of the best known fossil Elephas species were African. In fact Elephas probably originated in Africa (during the early Pliocene) and spent more of its evolutionary history in this continent than in Asia.

For previous TetZoo articles on proboscideans living and extinct, see…

Of dragons, marsupial lions and the sixth digits of elephants: functional anatomy part II, April 2008

RIP Yeheskel Shoshani, May 2008

How do you masturbate an elephant?, June 2008

The tangled mammoths, November 2008

Refs – -

Blashford-Snell, J. & Lenska, R. 1996. Mammoth Hunt: In Search of the Giant Elephants of Nepal. Harper Collins, London.

Carrington, R. 1958. Elephants: A Short Review of Their Natural History, Evolution and Influence on Mankind. Chatto & Windus, London.

Deraniyagala, P. E. P. 1958. The Pleistocene of Ceylon. Ceylon National Museums, Colombo.

Lister, A. M. 1995. Living in isolation. Geographical Magazine 1995 (Jan), 35-37.

Lister, A. M. & Blashford-Snell, J. 1999. Exceptional size and form of Asian elephants in western Nepal. Elephant 2, 33-36.

Osborn, H. F. 1942. Proboscidea: A Monograph of the Discovery, Evolution, Migration and Extinction of the Mastodonts and Elephants of the World. Volume II: Stegodontoidea, Elephantoidea. The American Museum Press, New York.

Tennent, J. E. 1867. The Wild Elephant, and the Method of Capturing and Taming it in Ceylon. Longmans, Green and Co., London.