If you’re a regular reader you might recall me making occasional lamentations about the near-absence of marsupial-themed content here. The recent Thylacoleo article was an unusual blip. But…

Caption: vombatiform diprotodontians alive and extinct at Queensland Museum, Brisbane, in 2019. At left, the giant diprotodontid Diprotodon. At right, a tame Common wombat Vombatus ursinus. Images: Darren Naish.

I have published a fair bit on marsupials in the past, the big problem being that the articles concerned (published during the ScienceBlogs and Scientific American years of Tet Zoo history) have been paywalled, ruined, or made very very hard to find in online archives. In particular, the Thylacoleo article reminded me that I published two articles on the diversity and phylogeny of diprotodontians way back in October 2011. But no matter what I tried, I couldn’t find them. Ultimately, I owe special thanks to David Gioia because they were still out there, just buried due to Scientific American changing its url (sigh). In the interests of recycling this material, here’s the first of these articles again. Now, 2011 is a long time ago and I’ve only made minor efforts to make updates, so this article isn’t exactly up to date. Much has been published on the fossil record of koalas since 2011, but notable new work has appeared on all the groups mentioned here. Please keep that in mind. Following the publication of Beck et al. (2022), I plan to publish a big review here of marsupial history and diversity overall, but hang tight because it’ll be a while before I’m ready to go on that. Anyway, without further ado…

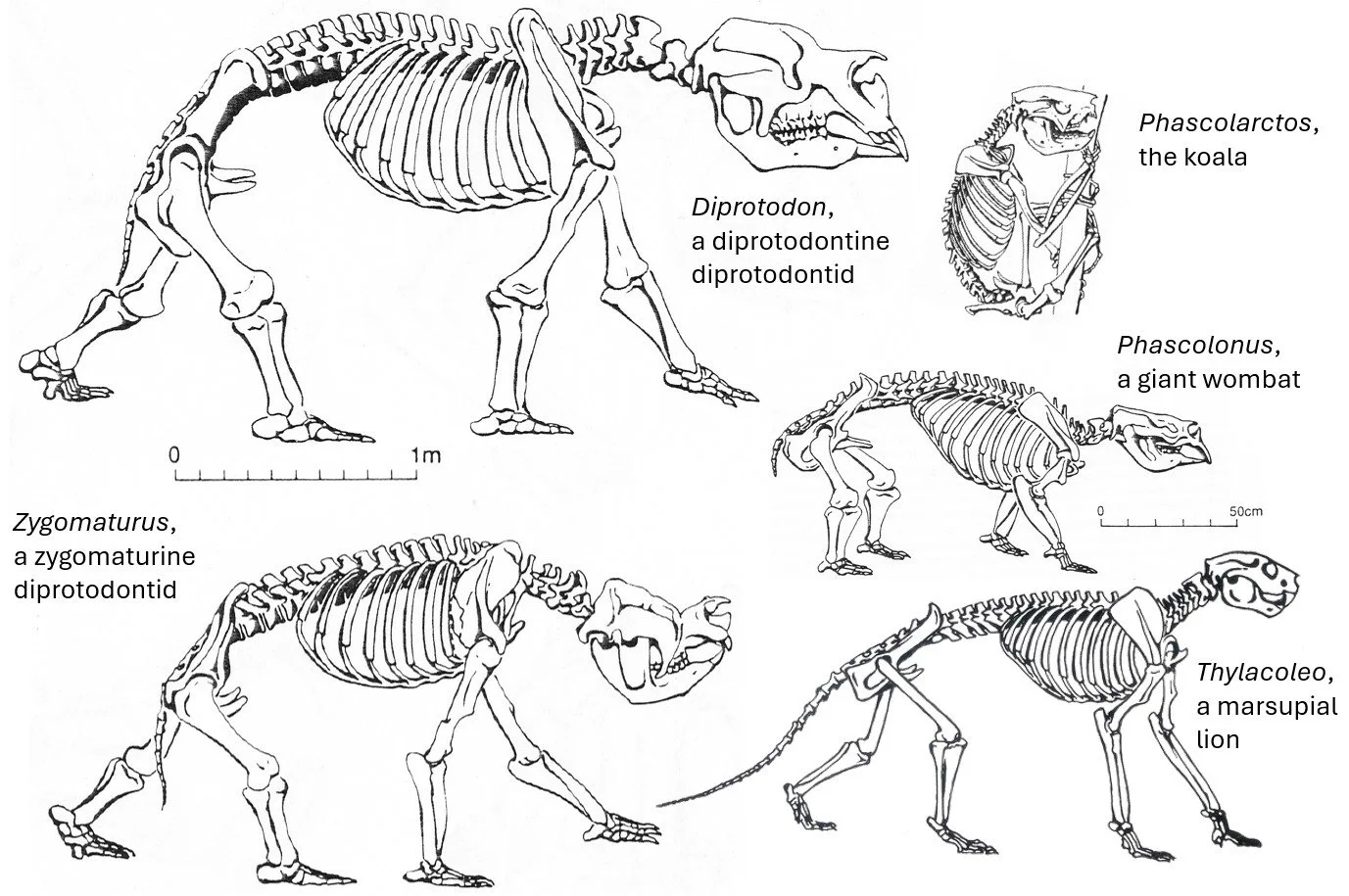

Caption: a montage of skeletal reconstructions of (mostly extinct) vombatiform diprotodontians, all by Peter Murray, from Murray (1991).

You’ve surely heard of kangaroos. What you might not know is that kangaroos (aka macropods) belong to a large, mostly herbivorous Australasian* marsupial clade termed Diprotodontia. Shared characters that unite diprotodontians include diprotodonty (where there are just two lower incisors), a special epitympanic wing of the squamosal bone in the braincase, and the presence of an extra band of fibres (termed the fasciculus aberrans) that connect the two hemispheres of the brain. The monophyly of Diprotodontia is also well supported by molecular characters.

* Some fossils from South America have been identified as diprotodontians but it looks most likely that these identifications are faulty.

In addition to macropods, ‘possums’ (petauroids and phalangeroids) are diprotodontians, as are the members of the koala-wombat clade, collectively termed Vombatiformes. Various different topologies have been suggested for Diprotodontia but most studies find vombatiforms to be the sister-group to a macropod + ‘possum’ clade (e.g., Amrine-Madsen et al. 2003, Horovitz & Sánchez-Villagra 2003, Asher et al. 2004). We’ll deal with macropods and possums some other time: the aim of this article (and the following one) is to review, as briefly and succinctly as possible, the vombatiform radiation. Here we go.

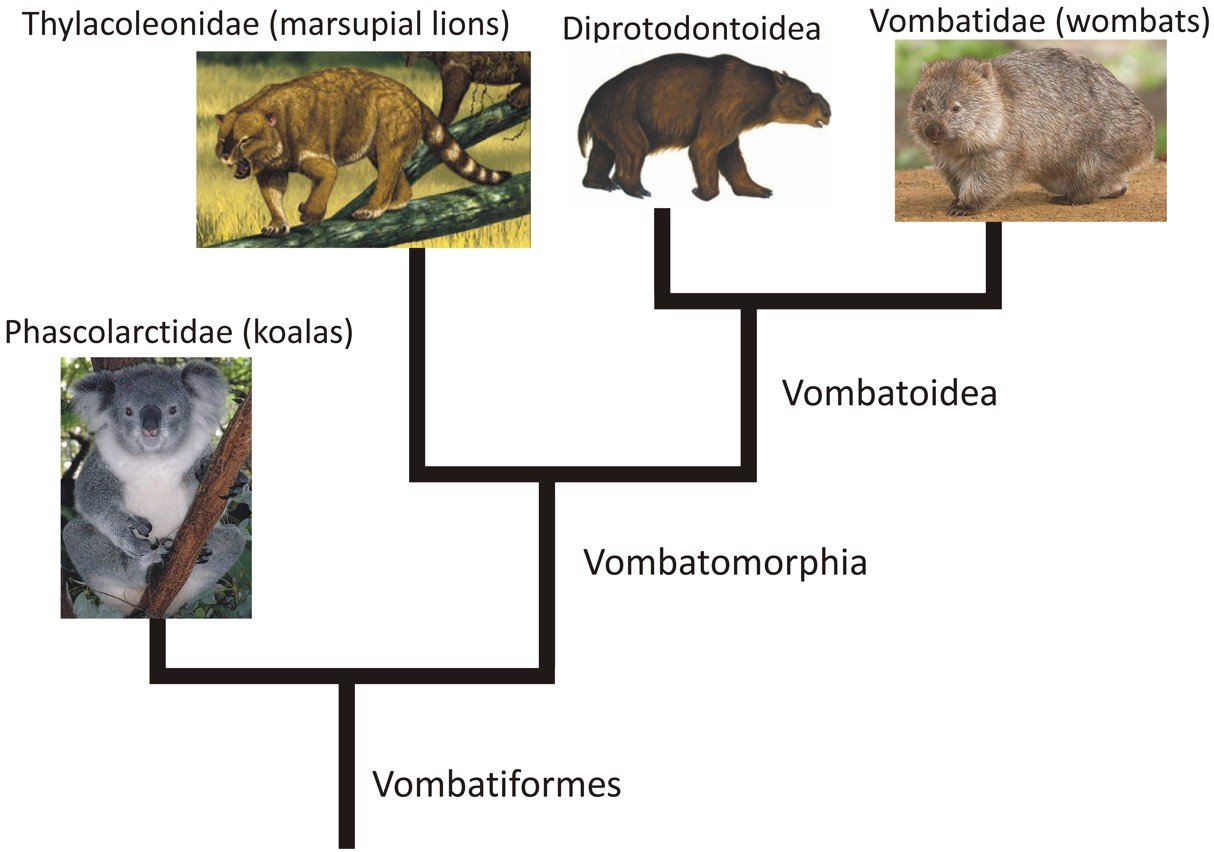

So far, very few published phylogenies incorporate data from fossil diprotodontians. There’s basically Munson (1992), with Archer et al. (1999), Weisbecker & Archer (2008) and some other studies depicting cladograms based on Munson’s work. These trees agree in showing koalas and marsupial lions to be outside Vombatoidea, a clade that includes diprotodontoids (Diprotodon and kin) and wombats. The term Vombatomorphia has been used (e.g., Black 2007) for the group that includes everything except koalas, in which case marsupial lions are non-vombatoid vombatomorphian vombatiforms (the adjacent, highly simplified cladogram should help). Molecular phylogenies dated with a representative sample of fossils indicate that the earliest divergences within Vombatiformes (e.g., that between koalas and vombatoids) occurred in the Eocene (Beck 2008).

Koalas past and present. Phylogenetic studies that sample fossil species have generally found the Koala Phascolarctos cinereus to be the sister-group to the rest of Vombatiformes. If you only sample extant marsupial species, you of course find the Koala to be the sister-taxon to wombats (Vombatidae), and this has created all kinds of amusing and erroneous assumptions about koala and wombat evolution (more on this in another article).

Caption: mother and juvenile Koala. Views differ on whether the juveniles of non-macropod marsupials should be called ‘joeys’ or not. My personal preference is that ‘joey’ should indeed be restricted to macropods, but I’m not doing on-the-ground work with live marsupials and will defer to consensus if that’s the way people want to go. If juvenile koalas aren’t ‘joeys’, what are they? Koalets? Image: Benjamin444, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

The ecomorphological and behavioural peculiarities of the living Koala are well known. Sedentary, solitary, arboreal and tailless, it has a proportionally small brain (0.2% of body mass) and enormous guts (proportionally, the largest of any mammal), is specialised for a diet of eucalyptus, is virtually able to go without drinking, and has an unusual hand where digits I and II oppose III-V* that it uses in hand-over-hand vertical climbing and clinging. It’s quite large for an arboreal folivore, with males exceptionally exceeding 20 kg. Koalas have selenodont molars (meaning that the cusps are lunate when seen in occusal view, with the concave side of the curve facing outwards) and hence are unlike most macropods and diprotodontoids, which are lophodont (that is, with transversely aligned ridges, or lophs). Koalas famously possess human-like fingerprints and I’m sure I’ve heard it said that a Koala fingerprint left at a human crime scene would seriously and unquestionably be assumed to be that of a human.

* This hand has sometimes been described as ‘zygodactyl’ but that’s arguably inaccurate. The term schizodactyl and forcipate have also been used.

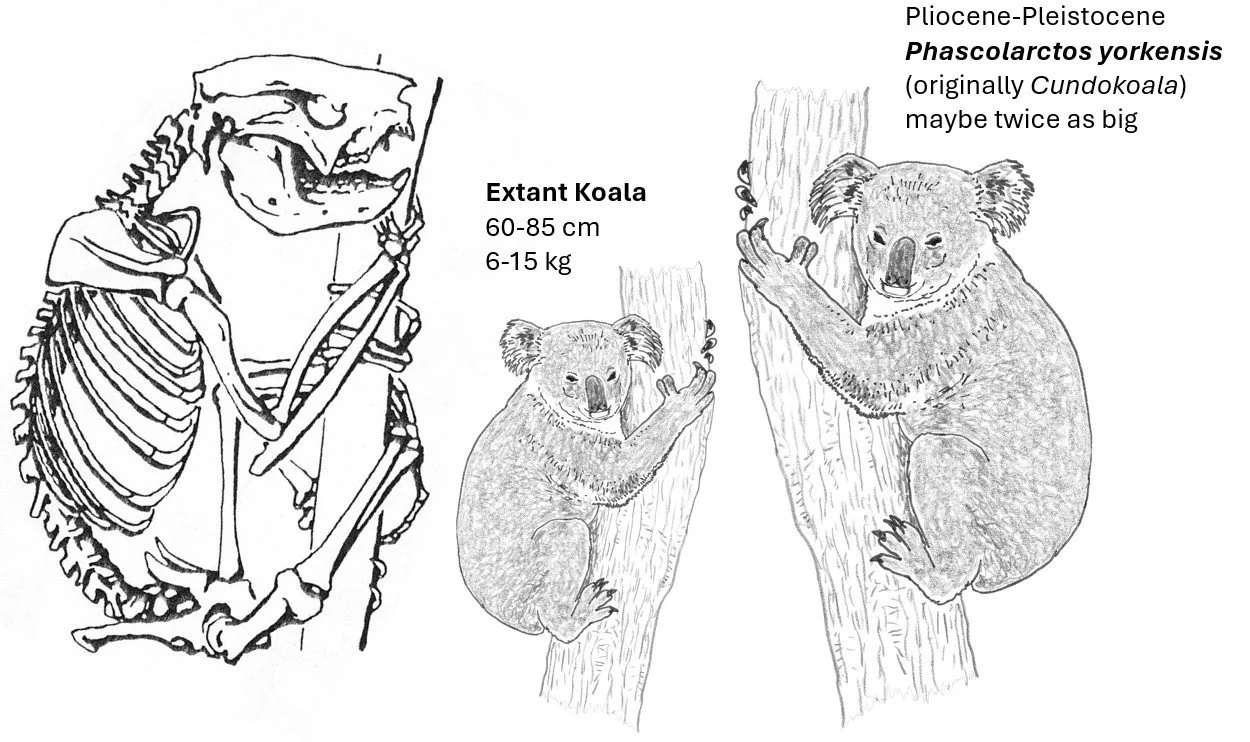

Caption: there are lots of interesting things to note in a Koala skeleton. Note the flat dorsal surface to the skull, the opposable digits in the hand and the short ribcage: with 11 rib pairs, they have the most reduced count of any marsupial. Image: Sklmsta, public domain (original here).

A descended larynx allows male Koalas to make especially loud roaring calls and sexual dimorphism is prominent, males being about 50% heavier than females and with broader faces, proportionally smaller ears, and with a large, odiferous chest gland. Despite common perception, the Koala is not fragile or over-specialised but actually able to tolerate an impressive diversity of wooded habitats. These range from moist, montane forests in the south-east of Australia to tropical vine thickets and rainforests in the far north, and to semi-arid woods in the drier parts of its range.

Koalas were commercially exploited at massive scale during the early decades of the 20th century, with more than 2 million animals killed for their skins in 1924 alone. Extensive local extinction and a range-wide population crash eventually led people to seek conservation measures for the species, though the large populations present historically are definitely a thing of the past. The prevalence of Chlamydia in wild Koala populations is well known and seems to be causing increasing mortality and declines in fertility in wild populations. The Chlamydia strains involved are the same as those found in domestic sheep and cattle, suggesting that Koalas have been infected by cross-species transmission.

Caption: skull of Nimiokoala greystanei from Louys et al. (2009). This differs from the skull of the extant koala in having narrower cheek teeth, more lightly built maxillary bones, and in having a palate that’s not as anteriorly displaced. It’s similar in features associated with hearing and noise-making though. Image: Louys et al. (2009).

Numerous fossil koalas (about 18 species) are known (the named genera are Madakoala, Perikoala, Nimiokoala, Litokoala and Invictokoala). None of these are much different from Phascolarctos and indicate that this group has been rather conservative during its history, apparently persisting since the Oligocene (or Eocene) at low diversity. Some are about half as big as the living species while one (P. yorkensis, originally given its own genus: Cundokoala) was about twice the size of it.

Comparison of these fossil forms to the living species has led authors to propose several interesting ideas about trends in koala evolution. Similar ear regions in fossil and living koalas suggest that a sedentary lifestyle and loud calling habit may have evolved early in the group, but differences in palate and tooth structure between Phascolarctos and other koalas suggest that the former is more strongly adapted for a tough, nutrient-poor diet (Louys et al. 2009). It has also been proposed that P. cinereas is a dwarfed version of giant Pleistocene versions of Phascolarctos, but this isn’t borne out by the fact that P. cinereas actually lived alongside its giant relatives during the Pleistocene (Price 2008).

Caption: at left, diagrammatic depiction of an extant Koala skeleton by Murray (1991). At right, a typical extant Koala shown to approximate scale with the Pliocene-Pleistocene species P. yorkensis. The extant Koala is highly variable in size and appearance (mostly in pelt length), but members of the group would have looked more variable in the geological past. Images: Murray (1991); Darren Naish.

Koalas have traditionally been given their own ‘family’, but some authors have also opted to reflect the distinctive nature of the lineage by erecting a ‘superfamily’ (Phascolarctoidea) and ‘infraorder’ (Phascolarctomorphia).

The incredible marsupial lions. Ok, a lot of this will be familiar reading if you read the article just published here. Thylacoleonids, marsupial lions or ‘thylacolions’ are among the most incredible of marsupials. Superficially possum-like features meant that they were regarded as members of Phalangeroidea for a few decades and I’ll admit that Thylacoleo does look – as many before have said – like a “giant murderous possum” in some artistic reconstructions (look at the photo of Phalanger gymnotis on p. 97 of the 1999 Walker’s Mammals of the Word: Sixth Edition, Volume 1 if you can). Though a few authors continued to hint at phalangeroid affinities for thylacoleonids as recently as the 1990s, cranial and other characters have generally led to their inclusion within vombatiforms, and as stem-members of the wombat lineage. Thylacoleo is thus better imagined as a “giant murderous wombat”, and I’m not the first to say that, either.

Caption: replica Thylacoleo skull on show at the Grant Museum of Zoology, London. The projecting and vaguely beak-like form of the incisors, massive size of the third upper premolar, and great depth of the zygomatic arch are all obvious. This photo was used previously in the Thylacoleo article here. Image: Darren Naish.

The largest and best known marsupial lion is of course the Pleistocene taxon Thylacoleo carnifex (first described by Richard Owen in 1858), but it isn’t the only one. We now know of various additional species, ranging in size from that of a typical tree squirrel to a leopard, from the Oligocene and Miocene, in addition to the additional Thylacoleo species T. crassidentatus and T. hilli from the Pliocene. The debate over the behaviour and feeding habits of Thylacoleo is well known and there’s no longer any substantive doubts over the specialised carnivory of these animals. Enormous shearing premolars give them one of the most specialised mammalian dentitions. Evidence from bite marks even shows that Thylacoleo ate (and preyed on?) the rhino-sized Diprotodon. In the hand, a pseudo-opposable thumb, enlarged thumb claw and slender metacarpals all suggest that Thylacoleo was capable of climbing, and its hindfoot anatomy is also consistent with climbing. By inference, smaller thylacoleonids were likely good climbers as well. Some authors have regarded it as a cursor but this seems odd given its rather stocky limb proportions.

Caption: a charge directed at many life reconstructions of Thylacoleo is that they make it look too much like a cat, and not sufficient marsupial-like, specifically diprotodontian-like. That’s certainly not the case for this very impressive painting, by Frank Knight and best known for its inclusive in the 1985 book Kadimakara: Extinct Vertebrates of Australia. Image: (c) Frank Knight.

The body size of Thylacoleo has been controversial and some authors have regarded it as a leopard- or lynx-sized animal of 40 or even 20 kg. These low estimates are difficult to accept given that its skull can be 26 cm long. Steve Wroe and colleagues concluded that an average mass for T. carnifex was most likely between 101-130 kg, with 164 kg being estimated for one individual (Wroe et al. 1999, Wroe 2000). It was massively robust and powerful, and certainly a capable predator of megafauna.

Caption: marsupials and their cousins (Marsupialia is part of the more inclusive clade Metatheria) have been covered a few times at Tet Zoo and I’m still well behind on the coverage I’d like to give them. Here are screengrabs from older articles; links are below.

We have to stop here, but we’re far from finished. We’ll look at the remaining vombatiform groups in part II, coming soon. For previous Tet Zoo articles on marsupials and other metatherians, see...

Of dragons, marsupial lions and the sixth digits of elephants: functional anatomy part II, April 2008

Invasion of the marsupial weasels, dogs, cats and bears... or is it?, June 2008

Long-snouted marsupial martens and false thylacines, July 2008

Marsupial 'bears' and marsupial sabre-tooths, July 2008

The ‘Tree-Kangaroos Come First’ hypothesis, October 2011

The Hunt for Persisting Thylacines, an Interview, March 2021

Thylacoleo, the Incredible Marsupial Lion, November 2025

Refs - -

Amrine-Madsen, H., Scally, M., Westerman, M., Stanhope, M. J., Krajewski, C. & Springe, M. S. 2003. Nuclear gene sequences provide evidence for the monophyly of australidelphian marsupials. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 28, 186-196.

Archer, M., Arena, R., Bassarova, M., Black, K., Brammall, J., Cooke, B. M., Creaser, P., Crosby, K., Gillespie, A., Godthelp, H., Gott, M., Hand, S. J., Kear, B. P., Krikmann, A., Mackness, B., Muirhead, J., Musser, A., Myers, T., Pledge, N. S., Wang, Y. & Wroe, S. 1999. The evolutionary history and diversity of Australian mammals. Australian Mammalogy 21, 1-45.

Asher, R., Horovitz, I. & Sánchez-Villagra, M. 2004. First combined cladistic analysis of marsupial mammal interrelationships Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 33, 240-250.

Beck, R. M. D., Voss, R. S. & Jansa, S. A. 2022. Craniodental morphology and phylogeny of marsupials. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 457, 1-350.

Black, K. 2007. Maradidae: a new family of vombatomorphian marsupial from the late Oligocene of Riversleigh, northwestern Queensland. Alcheringa 31, 17-32

Beck, R. M. D, 2008. A dated phylogeny of marsupials using a molecular supermatrix and multiple fossil constraints. Journal of Mammalogy 89, 175-189.

Horovitz, I. & Sánchez-Villagra, M. R. 2003. A morphological analysis of marsupial mammal higher-level phylogenetic relationships. Cladistics 19, 181-212.

Louys, J., Aplin, K., Beck, R. M. D. & Archer, M. 2009. Cranial anatomy of Oligo-Miocene koalas (Diprotodontia: Phascolarctidae): stages in the evolution of an extreme leaf-eating specialization. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29, 981-992.

Munson, C. J. 1992. Postcranial description of Ilaria and Ngapakaldia (Vombatiformes, Marsupialia) and the phylogeny of the vombatiforms based on postcranial characters. University of California, Publications in Zoology 125, 1-99.

Murray, P. F. 1991. The Pleistocene megafauna of Australia. In Vickers-Rich, P., Monaghan, J. M., Baird, R. F. & Rich, T. H. (eds) Vertebrate Palaeontology of Australia. Pioneer Design Studio (Lilydale, Victoria), pp. 1071-1164.

Price, G. J. 2008. Is the modern koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) a derived dwarf of a Pleistocene giant? Implications for testing megafauna extinction hypotheses. Quaternary Science Reviews 27, 2516-2521.

Weisbecker, V. & Archer, M. 2008. Parallel evolution of hand anatomy in kangaroos and vombatiform marsupials: functional and evolutionary implications. Palaeontology 51, 321-338.

Wroe, S. 2000. Move over sabre-tooth tiger. Nature Australia 27, 44-51.

Wroe, S., Myers, T. J., Wells, R. T. & Gillespie, A. 1999. Estimating the weight of the Pleistocene marsupial lion, Thylacoleo carnifex (Thylacoleonidae: Marsupialia): implications for the ecomorphology of a marsupial super-predator and hypotheses of impoverishment of Australian marsupial carnivore faunas. Australian Journal of Zoology 47, 489-498.