Once again it’s that time of year, by which I mean… spawnwatch season, of course.

Caption: peak spawning activity, occurring on 10th February. One important behavioural aspect to note is that activity occurs throughout daylight hours… just as it does throughout the night as well. I think that at least some frogs go for weeks without sleep during this period. Image: Darren Naish.

Yes, early February here in far southern England means that it’s once again that time when the lone amphibian species living in the grounds of Tet Zoo Towers – the Common frog Rana temporaria – gathers to breed. As ever, I’ve been keeping close tabs on things, so let’s see what happened this time round. There’s good news and bad news.

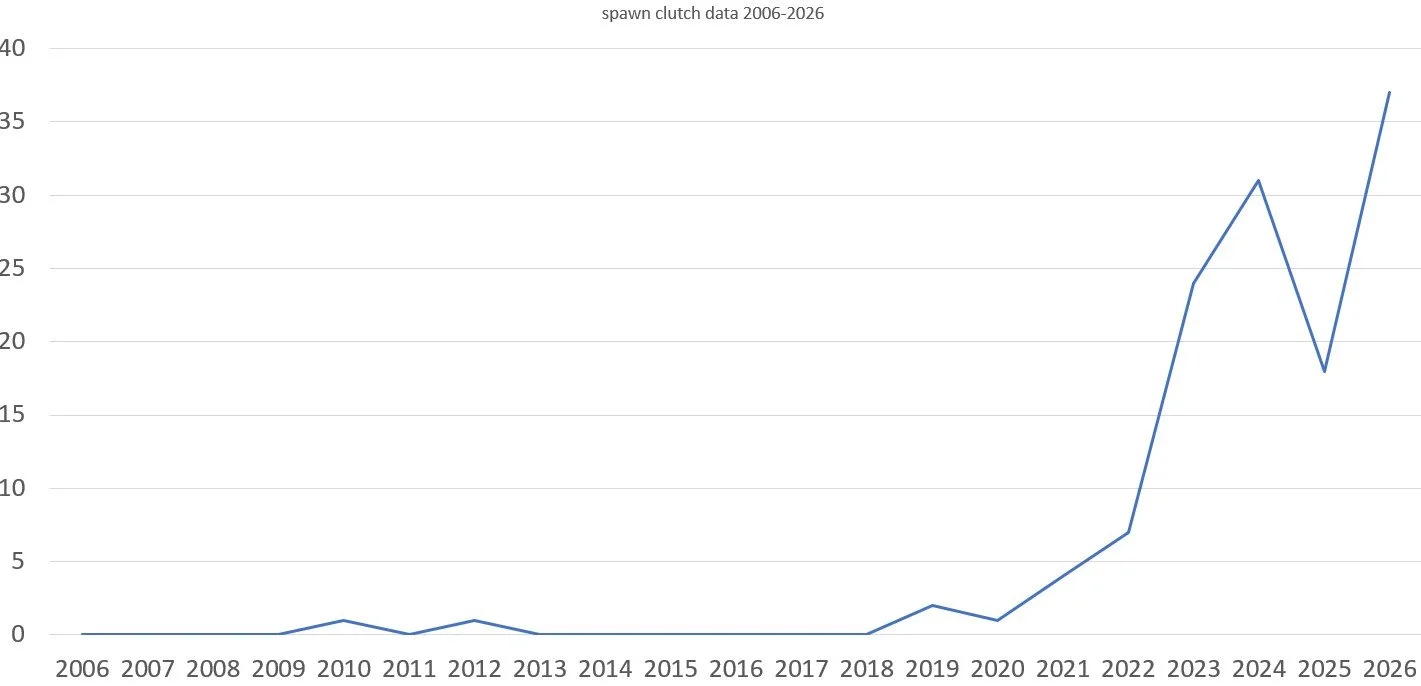

Some background. I’ve been maintaining ponds here at Tet Zoo Towers since 2006, initially with a rigid moulded pond, and more recently a large, pondliner-based one. Over that time, the number of adult frogs appearing in the ponds has increased from one or two to over 50, the number of spawn clutches increasing from one to a maximum of 31 (for 2024). In 2025, a cold weather spell caused an unusual break in breeding activity, and we never got above 18 clutches, which was surprising in view of the previous year’s high. I became worried that breeding females (which are typically the biggest frogs in the population and hence the most vulnerable to predation and maybe other things too) had disproportionally died off, and that the otherwise cumulative increase in our population was at an end, or even in reverse.

Caption: this is Plumpmot, a large and attractive female, here photographed in October 2023 with an earthworm. I didn’t see her during the breeding events of early 2026 and am not sure if she’s still around. Big females like this are especially important members of the population. Image: Darren Naish.

I should also add that the garden in which these ponds are sited is deliberately maintained for frogs and other animals. It’s a total mess and stands out markedly in contrast to the paved driveways and concrete death-yards otherwise so typical of the modern UK. There are tall hedges, piles of sticks, and any grassy areas are deliberately unkempt. In an age when people are, mostly, doing everything they can to obliterate every single scrap of greenery, I strongly believe that those of us who care should do everything we can to help the persistence of wildlife. We are fighting against those who want everything to be featureless concrete.

Caption: the look of pond 2 during early February following a couple weeks of constant, heavy rain. The water level is really high, and frogs are visible in parts of the pond that would be high and dry once the rain stopped. Note the vegetation and dead branches around the pond. These are there to provide refuge for frogs and deter pet cats. Image: Darren Naish.

As per usual, let me remind people in regions and nations that operate under what’s known as a continental climatic regime that, yes, the gathering and breeding of frogs at this time of year (early February) is normal for the mild, high latitude, maritime fringe archipelago in which I reside. A few decades ago, Common frogs here routinely started to gather and breed during the second week of February. Now, the first week is usual. Further to the west, in English counties like Cornwall, Common frogs regularly spawn in January, and late December spawnings are becoming increasingly common. I have a feeling that I’ve said all of this before, forgive me.

For a great overview of frog natural history in the UK you should consult Beebee and Griffiths (2000). More concise volumes include Inns (2009) and Beebee (2013). Cooke’s (2023) Tadpole Hunter is a very heavy and in-depth personal view of amphibian research in the UK that I’ve really enjoyed reading.

Things get underway. Male Common frogs are quite probably in a breeding pond throughout the whole of the winter, and hence ready to intercept arriving females and get things underway as early as possible. This year, a reasonable number of frogs (12) were readily visible on February 3rd, and two spawn clutches appeared on that day: a new earliest-ever record here (the previous was February 4th, for 2025). Constant heavy rain meant that the pond was at an all-time high, a fact that would have consequences once the rain actually died down…

Caption: daytime activity on February 7th, showing multiple spawn clutches in the shallow parts of the pond while frog combat and competition is very much underway. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: Common frogs are basically all recognisable as individuals on the basis of the dark markings on their dorsal surfaces and limbs. I’ve been trying to keep track of individuals but getting the right kind of photos is hard. Silviu Petrovan at the University of Cambridge has been leading a project that does this more properly. Image: Darren Naish.

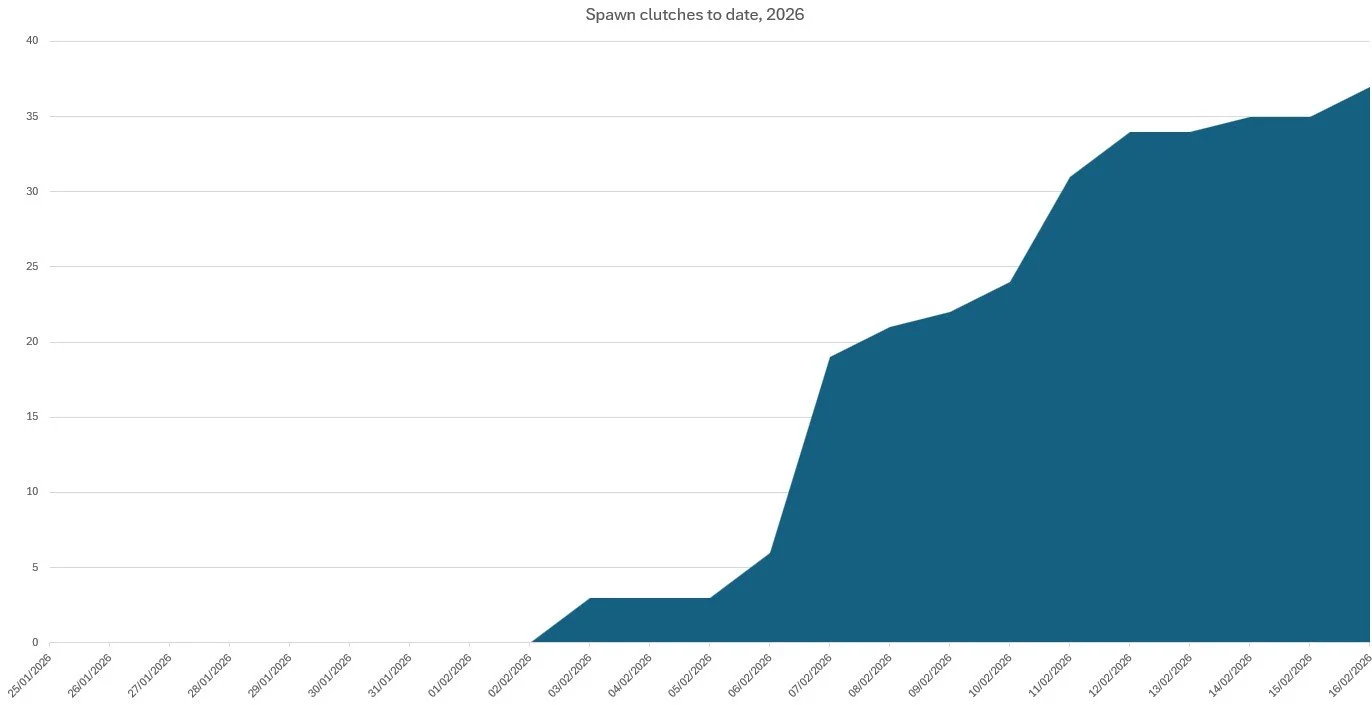

Over 43 frogs were visible by February 5th, and by February 7th a substantial jump to 19 spawn clutches had occurred, putting us above the 2025 total count. A day later, and I counted just over 50 frogs, and over the next several days the clutch count increased to 31 by February 11th, this number being the previous all-time record of 2024. After that, a slow and incremental climb to the current (as of February 17th) total of 37 occurred, a new all-time record. As you can see from the cumulative graph here, we’re now (at the time of writing) at an approximate plateau, activity has mostly stopped and the frogs have mostly dispersed. I won’t be surprised if one or two additional clutches appear, but we’re essentially there, and with a very impressive new clutch record. I hope to see this increase next year!

Caption: cumulative graph for 2026, showing how we quickly increased from two clutches on February 3rd to over 20 by February 8th, peaking with 37 clutches as of right now.

Caption: spawn clutches first appeared in our ponds here in 2010 (initially in an old plastic baby bath), but this graph shows how things improved markedly after 2020.

A rant on pet cats. As I’ve said ad nauseum before – forgive me – free-roaming pet cats are a perpetual, never-ending nuisance when you’re aiming to garden for wildlife. I live in constant dread of them killing various of the animals I cherish the most. Lone cats can and do wipe out entire families of fledgling birds and kill enough lizards, bats, frogs and other small animals to make a real difference to limited, isolated populations where there’s no migration from outside.

And a problem is not just that a lone cat from a neighbour’s garden will visit a wildlife-friendly garden ten, twenty, thirty, forty times a day, often staying there for hours at a time if allowed, it’s that this is often just one of many individuals that do the same. There are that many free-roaming pet cats. I’ve been using camera trapping in the garden for a while (see this article) and it’s disheartening to see how many pet cats – three, four, five – visit our property and hunt there during the day and night. This year, the camera trap let me down and only functioned for a single night (January 25th, days before spawning had started) before giving up, but it recorded three different pet cats on that one night.

Caption: pet cat 1, on the evening of 25th January.

Caption: pet cat 2, photographed a few hours later during the evening of 25th January.

For 2026, I observed one attack on a frog by a pet cat myself, purely by chance when I looked out of a window. It had pulled the frog out of the pond before being chased away, but the frog was lucky and survived. Several of our regular frogs have damaged eyes, bear scars and one (called Three-point-five) is missing a hindfoot, and it’s likely that cat attacks are among the events that have caused these injuries. At one pond I used to monitor, a pet cat killed or mortally injured 12 frogs in a day; it was total carnage and extremely depressing. Seeing as you’re reading this blog, it’s likely that you already care about the plight of beleaguered wildlife and are doing what you can to help it persist. But do what you can to help make others aware of this problem. I wish that things would change.

Caption: Common frogs probably select shallow spawning places since these are warmest and allow for the fastest development of the spawn and tadpoles, but the massing of the spawn that occurs might also afford protection, both thermally and in terms of ‘safety in numbers’. Images: Darren Naish.

To the future. I’ve surely said previously at Tet Zoo that I made extensive modifications to the bigger, newer pond at the end of 2024 such that it was substantially improved as a frog breeding site. Common frogs preferentially spawn in water less than 10 cm deep and large areas of very shallow water are ideal, not just for the act of spawning, but for fast development of the spawn and tadpoles. This in mind, I now create ponds with very large, shallow areas. And such it is with the modified pond here. It has worked to perfection, all the activity and spawning occurring in the very shallow end.

Caption: frog activity at the shallow end of the pond on 7th Feburary. Water level is high and very new spawn clutches are visible left and right. When spawn is fresh, it’s tight, compact and rubbery. As it ages, it soaks up water, expands and flattens out. Common frog spawn is remarkably resilient and extremely good at protecting the embryos from low temperatures, ice, rain, hail and mechanical damage.

Caption: we routinely have over 50 adult frogs massing in the pond during the breeding season now. When you combine this with the substantial number of juveniles that must be living in the same area, our population must be high. An aim of any successful conservation effort must be to have the population spread to appropriate habitat nearby. I hope that’s happening, but it’s not helped by the fact that we’re right next to a large and perpetually busy road. Image: Darren Naish.

But something is wrong. Round about February 8th, the water level started going down, and it did this so much that a few spawn clutches in the very shallowest area were ultimately left almost out of the water. This has undone a fair amount of my cleverly planned landscaping and means that I’ll have to renovate things in the future. I have no idea what’s caused this but it can only be a puncture, though how this came about I have no good idea. This isn’t an immediate disaster, since even the somewhat high-and-dry spawn is ok (Common frog spawn spreads out and there’s still enough water in that part of the pond for the embryos, once free of the jelly, to remain in water), but it is a pain. At the time of writing (February 17th), much of the shallow end is dry and I’ve had to do an emergency rescue of all the spawn. I’m going to have to do a rebuild. Again. The spawn and tadpoles will be ok though, don’t fear.

Caption: February 17th, and the water level has dropped a worrying amount. All the spawn has been (temporarily) placed in a large shallow tray and the pond will need rebuilding. These things happen.

I guess a pondkeeper’s pondwork is never done.

For previous articles on frogs, ponds, and spawning events, see…

A Love Letter to the Common Frog, August 2020

Live Spawnwatch Action From Pond 2 at Tet Zoo Towers, February 2024

News From the Pond's Edge: Spawnwatch 2025, February 2025

Suburban Camera Trapping, Week 1, May 2025

Refs - -

Beebee, T. 2013. Amphibians and Reptiles. Pelagic Publishing, Exeter.

Beebee, T. & Griffiths, R. 2000. Amphibians and Reptiles. HarperCollins, London.

Cooke, A. 2023. Tadpole Hunter: A Personal History of Amphibian Conservation and Research. Pelagic Publishing, London.

Inns, H. 2009. Britain’s Reptiles and Amphibians. WILDGuides, Old Basing, Hampshire.