I’m not sure that I’ve ever written about shrews at TetZoo (except in passing; see links below). It’s time to rectify that...

Caption: shrew skeletons are pretty phenomenal, the long skull and massive teeth in particular are striking. This oft-reproduced illustration (from Allain 1917) depicts Crocidura above and Scutisorex below. Incidentally, I think we’d imagine these animals to look like tiny mustelids if we only knew of them from their skeletons. Image: Allain (1917).

Shrews (united in Soricidae) are small, mostly insectivorous mammals closely related to moles and hedgehogs and united with them in Eulipotyphla*. They’re a large family, containing over 440 species. Shrews are notable for their voracious appetites, frenetically rapid foraging behaviour, short lifespans (typically less than 1.5 years), formidable pointed teeth and flexible snouts. The skull is robust, vaguely cylindrical and with fused sutures. The body is muscular and tubular, and this – combined with the head shape – allows them to burrow and push through leaf litter and soil as they hunt. They don’t all live like this though, since some swim and others climb. Other typical features include tiny eyes, sometimes reduced or even absent pinnae, a velvety pelt, slender hands and feet and a slim, pointed tail.

Captions: lipotyphlans - or eulipotyphlans if you must - are both a familiar and mysterious group of mammals. Various hedgehog, mole and shrew species are familiar to some of us (I’m in western Europe, and have thus encountered such animals many times), but there are other lipotyphlan groups of far more restricted distribution. These images are from my in-prep textbook. Images: Darren Naish.

* Shrews, moles, hedgehogs and solenodons were long grouped together with tenrecs and golden moles in a group termed Lipotyphla, which formed the core of an even more inclusive group previously termed Insectivora. As genetic evidence piled in during the 1990s and 2000s, it became obvious that pre-1999 Lipotyphla was not a natural group (tenrecs and golden moles are afrotherians), and that only shrews, moles, hedgehogs and solenodons actually belong here. The term Eulipotyphla (meaning ‘true lipotyphlans’) was applied to this ‘core Lipotyphla’ in 1999 and is now in widespread use. But there’s no reason at all why we shouldn’t still be using Lipotyphla: it’s available, has priority, isn’t in use for anything else, and the removal of some groups previously included here doesn’t mandate that we now need a new name. See also the similarly pointless ‘Cetartiodactyla’.

Glands on the flanks give off an odour which is said to be repellent to most predators and perhaps to other shrews. Despite this, shrews still get killed and eaten by cats, snakes, raptors, owls and other predators.

Caption: I’ve seen Common shrews Sorex araneus on many occasions, mostly in a deceased state. Shrews die from shock when subjected to loud noises (like thunder), and may even die when they find themselves exposed in the open. The individual shown at left is photographed as discovered, in an open area in the Gloucestershire countryside. Shrews are also predated upon by owls a lot. At right, we see four individual retrieved from the stomach of a single Barn owl Tyto alba (which was itself a roadkill). Images: Darren Naish.

Shrew teeth are remarkable. For starters, shrews are born with their permanent, adult dentitions (the first tooth set is shed while they’re embryos) and at least some individuals of some species die due to starvation as their teeth become too worn to allow prey capture. Shrews can actually be aged on the basis of their tooth wear. The anterior-most incisors are proportionally massive and have a pincer-like function. The tooth cusps of those shrews grouped together in the subfamily Soricinae are reinforced by iron at their tips and are thus reddish, so the whole lot are sometimes called red-toothed shrews. Shrew molars have prominent cusps arranged in a W-shaped pattern and appear built for breaking up insect chitin.

Caption: shrew skulls are remarkable. Note the mostly fused nature of the bones, the lack of a bony bar connecting the maxilla to the rear of the skull, the hypertrophied, pincer-like, serrated incisors, and the iron-enriched, reddish tooth cusps. This is an Ornate shrew Sorex ornatus skull. Image: US National Parks Service Museum Collection, public domain (original here).

Another peculiarity is that some species are truly venomous and conduct venom into the tissues of prey during biting. The venoms concerned are surprisingly potent. Many books mention the fact that American short-tailed shrews (Blarina) can produce enough venom to kill about 200 mice – Blarina venom contains a protease called blarinasin – and it’s also said that shrew venom causes great discomfort in humans. Using this venom, shrews like Blarina and the Neomys water shrews are able to immobilise animals about twice as large as themselves (including rodents, frogs, lizards and fishes; Haberl 2002) and also to store prey alive. A few fossil shrews have grooves on their incisors that have been identified as a specialised envenomation apparatus (Cuenca-Bescós & Rofes 2007), though long-time readers of this blog will know that tooth grooves in mammals are not necessarily anything to do with envenomation.

The majority of shrews are insectivorous and feed on arthropods, ranging from tiny mites all the way up to insects similar in size to themselves. Earthworms, nematodes and other invertebrates are consumed too; as mentioned above, some species eat frogs and even rodents, small birds (yes, they can catch and kill birds like finches), small snakes, and carrion. Seeds, nuts and other plant parts are eaten by a few species.

Several shrew species belonging to the genera Sorex and Blarina are known to echolocate: they emit ultrasonic squeaks and are able to gain a crude understanding of objects nearby. Elsewhere in terrestrial mammals, echolocation is also said to be present in solenodons and tenrecs (and there are humans who use it too).

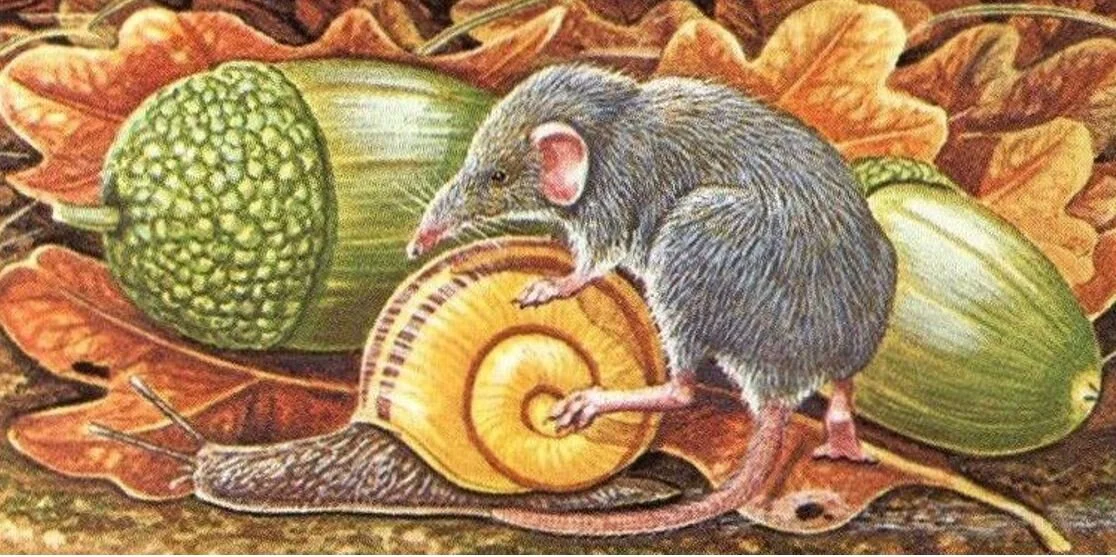

Caption: I’ve always liked this illustration, deliberately composited to show how small the smallest shrews are (snails can be variable but most people have a rough idea how big an acorn is). It’s from the 1985 PG Tips Incredible Animals card set; I think the artist is Richard Orr.

A few shrews are famously small. The Etruscan shrew or Pygmy white-toothed shrew Suncus etruscus of the Mediterranean region can be adult at 1.6 g (but also as heavy as 2.4 g) and be 6.5 cm long, and has often been described as the world’s smallest mammal. Because, however, ‘size’ in animals refers to mass rather than just length, most sources agree that Kitti’s hog-nosed bat Craseonycteris thonglonyai – also known as the Bumblebee bat for obvious reasons – should be regarded as the smallest living mammal instead, though the measurements are close and variation actually means that the two species overlap. Worth noting here is that a fossil mammal from the Eocene of Wyoming – Batodonoides vanhouteni, a member of the extinct family Geolabididae – might have been even smaller than both the tiniest shrew and the tiniest bat, with some estimates suggesting a mass of around 1.3 g (Bloch et al. 1998). Anyway, at the other end of the scale, the largest living shrew – the African forest shrew or Goliath shrew Crocidura goliath (previously Praesorex) – is claimed to be a veritable behemoth, reaching 29 cm according to some sources (Barnard 1984). I’m somewhat disturbed by the concept of a shrew 29 cm long and can’t help but think that this is an error (incidentally, the same source gave this giant shrew a mass of just 35 g, which surely can’t be correct). And indeed this might be wrong, since a later source credits the Asian house shrew Suncus murinus as the biggest shrew, and gives its total length as 15 cm and mass as 106 g (Searle & Barnard 2001).

Shrews are widely distributed, occurring throughout Eurasia, Africa and North America. They’ve colonised South America within geologically recent times such that 11 species, all belonging to the same genus (Cryptotis), presently occur on this continent too, though the species concerned are so far limited to the Andes. The tiny size of shrews and their propensity to hide among masses of vegetation transported by people as livestock food or bedding also means that some species have been able to colonise islands thanks to human transportation.

Caption: a few shrew taxa are chunky and superficially mole-like. This is a Taiwanese mole shrew Anourosorex yamashinai. Image: Pei-Jen Lee Shaner, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

When it comes to body shape and ecology, shrews are generally conservative. But that’s not entirely fair. There are robust, superficially mole-like, semifossorial shrews (like Surdisorex in Africa and Anourosorex in eastern Asia), gracile, long-tailed scansorial shrews (like the Sylvisorex climbing shrews of the African tropics), various amphibious shrews, and the remarkably odd, robust-bodied African hero shrews (Scutisorex). As is well known, Scutisorex has a reinforced, lengthened spine which provides it with ridiculous ability to resist compression. It’s famously said to be able to withstand the weight of an adult person. This configuration also means that its pelvis is displaced far to the posterior and that it has an atypical gait (Kingdon 1997).

Caption: hero shrews (Scutisorex) have a remarkably long, ultra-modified spine and a distinctive hunched posture. At times, they can put on a lot of weight and become quite sausage-like. There are two Scutisorex species, one of which (S. thori) was named in 2013. Image: Peter Spelt, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Shrews also differ a fair bit in the length of the tail, in the size and presence of the pinnae (they’re large in some and entirely absent in others, like the Surdisorex African mole shrews of Kenya), and in the length of the claws and form of the hands and feet. Certain swimming shrews – most famously the Neomys water shrews – have fringes of stiff hairs on the hands and feet while the highly unusual, short-snouted Elegant water shrew Nectogale elegans of southern Asia has webbed digits in addition to hair fringes. We also know of unusual fossil shrews that were equipped with flattened molars and might have been specialised frugivores (Hutchison & Harington 2002).

Caption: several competing phylogenies for shrews are available, and here’s a massively simplified, consensus one. Stay tuned, as we’ll see more complex cladograms in future articles. As usual, the illustrations here are for my in-prep textbook, which I despair of ever finishing. Image: Darren Naish.

Shrews are extremely species-rich as a family: among mammals, only murids (rats and mice), cricetids (New World mice, voles and kin) and vesper bats contain more. Traditional classifications break shrews into three living subfamilies: the mostly African-Asian Crocidurinae (named for the Crocidura white-toothed shrews), the African Myosoricinae (Congo shrews, mouse shrews and mole shrews) and the mostly Eurasian and North American Soricinae (or red-toothed shrews). But does this classification reflect what we now understanding of phylogeny?

And it’s at this point that I need to stop. This was but a brief introduction to shrews as a whole. When we revisit them, we’ll look at their diversity and phylogenetic history in more detail.

For previous TetZoo articles which mention shrews and other lipotyphlans … or eulipotyphans, sigh … see…

The first new European mammal in 100 years? You must be joking, October 2006

My dead mole, June 2008

Refs - -

Allen J. 1917. The skeletal characters of Scutisorex. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 37, 769-784.

Bloch, J. I., Rose, K. D. & Gingerich, P. D. 1998. New species of Batodonoides (Lipotyphla, Geolabididae) from the Early Eocene of Wyoming: smallest known mammal? Journal of Mammalogy 79, 804-827.

Cuenca-Bescós, G. & Rofes, J. 2007. First evidence of poisonous shrews with an envenomation apparatus. Naturwissenschaften 94, 113-116.

Haberl, W. 2002. Food storage, prey remains and notes on occasional vertebrates in the diet of the Eurasian water shrew, Neomys fodiens. Folia Zoologica 51, 93-102.

Hutchinson, J. H. & Harington, C. R. 2002. A peculiar new fossil shrew (Lipotyphla, Soricidae) from the High Arctic of Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 39, 439-443.

Kingdon, J. 1997. The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. Academic Press, San Diego.