In which I once more rescue an article from the broken Tet Zoo archives, this time from ver 3 at Sci Am, and specifically from November 2011…

Adrian Shine's A Natural History of Sea Serpents

Yowies and the Marsupial Hominoid Hypothesis – Neil Frost’s Fatfoot: Encounters With A Dooligahl

Nessie Point and Counterpoint; Who Owns the ‘Facts’ on the Loch Ness Monster?

Regular readers of this blog might be aware of my book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, initially published as an ebook in 2016 (Naish 2016) and appearing in hardcopy in 2017 (Naish 2017)…

Werewolves in America; the Tale of Dogman

The Strange Case of the Minnesota Iceman, Part 2: A Review of Heuvelmans's Neanderthal

Time for the second part in my Minnesota iceman series. The article you’re able to read was originally published at ver 3 (the Sci Am years) in two separate parts. For the first part on the Minnesota iceman, go here…

The Strange Case of the Minnesota Iceman, Part 1

Legend of the Black Dog

Santa Cruz’s Duck-Billed Elephant Monster, Definitively Identified

What Was the Montauk Monster? A Look Back to 2008

eDNA, Footprints and the Biological Bigfoot: Comments on an Interview With Jeff Meldrum

The Hunt for Persisting Thylacines, an Interview

The Lake Dakataua ‘Migo’ Lake Monster Footage of 1994

Morgawr and the Mary F Photos

The Case of the Cadborosaurus Carcass: a Review

Monsters of the Deep, a Ground-Breaking Exhibition at the National Maritime Museum, Cornwall

The 1972 Loch Ness Monster Flipper Photos

If you’re a long-time reader of TetZoo, you’ll know that I’ve often examined and discussed the backstories to famous monster photos. And if you follow me on Twitter (I’m @TetZoo), you’ll know that I’ve lately been posting extremely long threads wherein I do likewise. It’s fun and results in lots of interaction. Today, I’m going to conduct an experiment and publish a monster-themed article here at the blog AND a threaded version of the same text at Twitter.

Lore of the Loveland Frog

At least some of you reading this will know my 2013 book The Cryptozoologicon, produced in collaboration with John Conway and C. M. Kösemen (Conway et al. 2013).

Caption: at left, cover of the 2013 book The Cryptozoologicon. At right, a scene from the book’s interior, depicting yetis in a Himalayan scene; by John Conway. Image: Conway et al. (2013).

The Cryptozoologicon is devoted to cryptids; that is, to mystery animals. After describing a given cryptid and proposing how it might actually be explained (sadly, most cryptids now seem to be sociocultural phenomena or the products of fakery or human error, not valid biological entities; Naish 2017), we go on to indulge in a bit of speculative zoology: that is, a bit of ‘what if’ speculation whereby we imagine ourselves inhabiting a parallel universe where cryptids are real (Conway et al. 2013)…

TetZoo regulars will know that a sequel to The Cryptozoologicon – it’s working title is The Cryptozoologicon Volume 2, duh – has been planned for some time, and we still aim to complete it ‘soon’. Which creatures will be covered in this soon-to-be-published work? I’m not saying, but the article you’re reading now concerns one, just one, of the cryptids we’ve included.

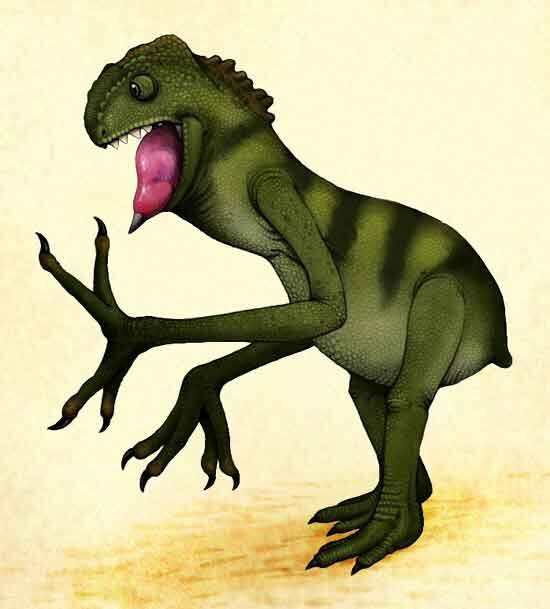

Caption: I really think that some artists have made the Loveland Frog look substantially too frog-like, and this is one of the most extreme examples. But, hey, it’s a nice and technically very competent piece of art. Nice to see Pioneer Dork being used as a scale bar. Image: artist unattributed, Cryptid Wiki (source).

Books on ‘mystery animals’ – cryptids and the like – include a veritable panoply of the weird, unbelievable and ridiculous. Among these, one of my favourites is the Loveland Frog (sometimes called the Loveland Lizard, but that’s just silly): a bipedal, vaguely reptilian animal, similar in size to a child, and supposedly encountered several times in the vicinity of Loveland, Ohio, USA between 1955 and 1972… and there are a few more recent claimed sightings too. The sightings describe greyish, bipedal creatures, said to have a frog-like head, bulging eyes, a leathery, reptile- or amphibian-type skin, and a standing height of between 3 and 4 feet.

The Loveland Frog has been discussed and revisited several times in the mystery animal literature, the tales recounted here having previously been published in Bord & Bord (1989), Newton (2005) and Shuker (2008)*. I especially like Bord & Bord’s (1989) section on the case because it includes the wonderful illustration you see below, produced by Ron Schaffner, and evidently based on a pencil drawing produced by one of the witnesses.

* Confession: I didn’t have Loren Coleman’s Mysterious America to hand while writing, nor W. Haden Blackman’s The Field Guide to North American Monsters. I understand that these works also include coverage of this creature.

Caption: Ron Schaffner’s evocative illustration of the Loveland Frog, very obviously based on the pencil sketch shown below. Note the suggestion of cranial horns, the rows of parasagittal spines and the oval eyes. Image: Ron Schaffner, from Bord & Bord (1989).

Sources that discuss the Loveland Frog most usually recount the observation of police officer Ray Shockey (though spelt Shocke in some sources) who stopped to observe a creature seen crossing the road at 1am on March 3rd 1972, when it was cold enough for the road to be icy. Shockey’s creature was in a crouching position but then stood erect and stared in Shockey’s direction before climbing the guardrail separating the road from the ground that slopes down to the Little Miami River (Newton 2005, Haupt 2015). Other officers later came out to check Shockey’s observations. There’s some talk of them finding scratch marks on the guardrail but efforts to locate photos verifying the presence of said scratches haven’t been successful (Haupt 2015).

Caption: A pencil drawing of the Loveland Frog, I assume that made by Ray Shockey (though I’ve been unable to confirm this; I found it, unattributed, at various sites online and haven’t seen it in print). The artist evidently had quite some skill.

An account similar to Shockey’s was made by another police officer – Mark Matthews – two weeks later, and this again involved the animal being encountered on the road at night and seen from a patrol car. Matthews was concerned as the creature stood up from a crouched stance and fired his gun at it – yee-haw!! ‘Murica!! – and seemingly injured the animal. Again, it climbed out of sight over the guardrail.

Caption: another depiction of Shockey’s frogish encounter, this time showing the creature with a sumptuous butt and disturbingly human-like physique. This image is widely available online but I’ve been unable to find the artist’s name.

But Matthews later claimed that none of this was accurate, that he’d actually seen a big lizard (an escaped pet iguana?), and that he’d augmented the story as a way of making his colleague (Shockey) seem like less of a nut. I really like the deep investigation of this account provided by Ryan Haupt for the Skeptoid Podcast (here; Haupt 2015). It provides lots of additional information and is clearly substantially more reliable than the recountings of events provided in standard cryptozoology- and paranormal-themed websites and publications. Haupt states that there’s what appears to be an email confession from Matthews whereby the account was dismissed as being ‘blown out of proportion’, though its authenticity (it – the ‘confession’ – appears to have originated from this 2001 article from X-Project Paranormal Magazine) is doubtful. An implication that a big lizard might have been seen must also be considered doubtful in view of the icy conditions (and cold temperatures) of the time. A big lizard would be hiding away somewhere, not out and about. Apparently, there’s a sketch that accompanies either Shockey’s or Matthews’s account (Newton 2005; though his text seems to combine both accounts into a single sighting); I assume it’s the pencil one shared above. A local farmer is also said to have seen a Loveland Frog shortly afterwards but details are hazy.

Caption: images showing all three of Hunnicut’s Loveland Frogs together are rare, but at least there’s this fine piece of work by John Meszaros. Image: Cryptids State-by-State, John Meszaros (source).

The oldest Loveland Frog story pre-dates these 70s one and concerns a sighting made on an Ohio roadside during the early morning of May 25th 1955. The story goes that a businessman or travelling salesman – sometimes said to be unknown and sometimes specifically identified as Mr Robert Hunnicut (Newton 2005) – was driving home from work when, at 3.30am, he saw three bipedal, greyish reptilian creatures, each about 3 feet tall. The witness stopped and observed them for a few minutes. In some versions of the story, the creatures were seen ‘conversing’, in some they were observed under a bridge, and in some one of them held a cylindrical or wand-like device above its head. This released sparks and was frightening enough that it inspired the witness to flee.

Post-1972, the Loveland Frog has been rare. There’s a 2016 event in which two teenagers – out playing Pokémon Go, apparently (this isn’t a sexual euphemism) – supposedly saw and even photographed what appears to be the creature. But as you can see for yourself, this event is almost definitely a hoax.

Caption: a still from the 2016 footage taken by Sam Jacobs and his girlfriend. The actual footage is exceedingly dark and this image has been brightened as much as possible (by the people at Fox19 News). Some think that the photo actually shows a lawn decoration with added lightbulbs. Image: Fox19 News (source).

Explaining the Loveland Frog, or trying to. Given the several peculiarities of the 1955 ‘three creatures’ account, it’s not surprising that some authors have sought to identify the Loveland Frog as an alien rather than an unknown denizen of Planet Earth. Assuming that Loveland Frog accounts represent actual observations, an explanation mooted by some authors is that they could be confused descriptions of escaped pet iguanas or monitor lizards (Bord & Bord 1989). This is hard to accept given the bipedal postures that witnesses reported, plus the descriptions don’t recall big lizards at all. At a stretch we might consider that big lizards in fleeting bipedal or erect-standing poses were witnessed, with substantial embellishment and confusion resulting in substantially modified descriptive accounts, but the cold temperatures present during some of the sightings also count against this idea.

Perhaps, some might suppose, these fleeting glimpses of big escaped lizards were inadvertently (or deliberately) combined in the minds of the witnesses with their prior knowledge about the ‘big frog monsters’ already said to inhabit the Miami River region. Such stories go back to the 1950s at least and it should be noted that a similar-sounding entity, the ‘Lizardman’, was reported during the 1970s from South Carolina, New Jersey and Kentucky. In other words, there seems to be lore in the region about such creatures… which might mean that any fleetingly-glimpsed, unidentified weird animal could morph into a monster of this sort in the memories of witnesses.

Caption: this is the very best photo of the South Carolina Lizardman, though sadly I couldn’t find the version with the top hat and cane. Taken by a mysteriously anonymous source.

Also worth noting is that the 1950s were the time when amphibious fish-monster creatures were being depicted on the big screen. The sensational and highly popular Creature from the Black Lagoon premiered in 1954 and could well have inspired people – consciously or not – to think or pretend that they might really encounter ‘frog people’ or ‘lizard people’ of this sort.

Caption: is it really coincidental that the Creature from the Black Lagoon appeared the year prior to the first appearance of the Loveland Frog? Well, probably not. Image: public domain (original here).

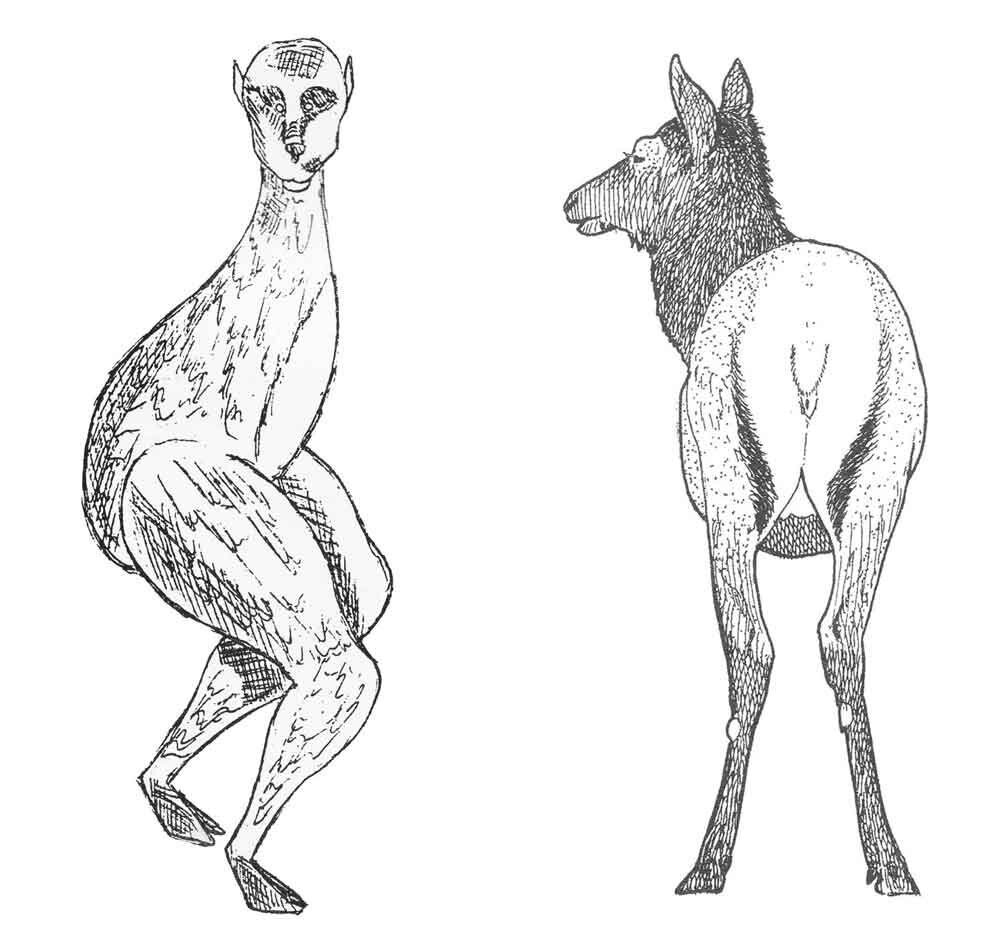

One more thing. If we’re going to take seriously the idea that Hunnicut and the other alleged witnesses saw real animals and misidentified them, the possibility that they saw big reptiles has to be considered quite unlikely, as noted above. Deer, standing at the roadside and seen in front view, sometimes look like humanoid bipeds since their bodies, hindlimbs and snouts merge into invisibility. I came up with this idea myself after seeing a scary roadside ‘biped’ with a round body, wide neck and slender legs morph into a deer as the car I was in approached and passed it, and I think that a few very odd sightings of similar creatures (like John Irwin’s Wharton State Forest monster of December 1993; Coleman 1995) could be explained the same way. Could confused observations of this sort explain creatures like the Loveland Frog? It’s worth considering.

Caption: how do we explain (or attempt to explain) ‘monster’ sightings like the creature reported by John Irwin in 1993? Irwin’s drawing (from Coleman 1995) is shown at left. The ‘monster’ here has several deer-like features. Could it be that Irwin saw a foreshortened deer and misinterpreted it as a biped? The deer image at right (a Wapiti female) is from Geist (1999). Images: Coleman (1995), Geist (1999).

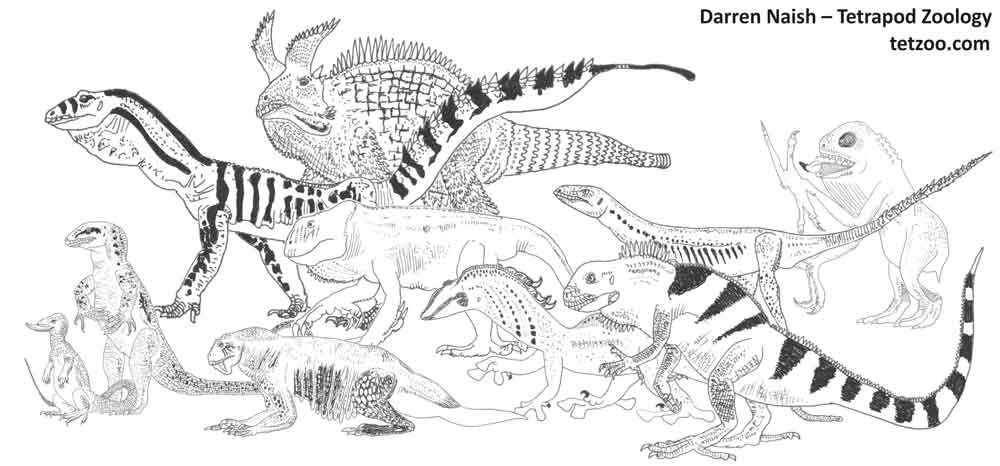

It came from the Squamozoic. The existence of metre-tall, bipedal reptile-like creatures has to be regarded as fairly unlikely, especially when those reptile-like creature are seen carrying mechanical devices that emit sparks. The real identity behind the creature is obvious, but only if we admit the reality of parallel universes, time travel, and the ability of some creatures to somehow move between disparate points in space and time.

The Loveland Frog was no giant, humanoid frog at all, but actually a giant, vaguely humanoid lizard, and specifically one of the short-faced, big-brained iguanians from the parallel Earth of the Squamozoic.

Caption: short-faced, tailless, bipedal body forms evolved on a few occasions among the iguanians of the Squamozoic, most famously in the terrameleons (this is a Terrible terrameleon). It’s not a big step from here to time-travelling, intelligent, tool-using iguanians in 20th century Ohio. Image: electriceel.

On Squamozoic Earth, squamates (lizards, snakes and amphisbaenians) evolved to dominate the large-bodied animal fauna of the planet, and heightened intelligence evolved on several occasions. We conclude that the Loveland Frog is one of the intelligent American iguanians, presumably one that comes from a point in time somewhere in the future relative to our own position in the timeline. Whether these intelligent, parallel-universe iguanians have learnt to master time-travel and hence are deliberately travelling to 20th century Ohio as part of an exploratory or invasive mission, or whether they are merely falling inadvertently through some sort of interdimensional window, we cannot know, but perhaps we will in time.

Caption: a large, intelligent iguanian from the Squamozoic surely explains the Loveland Frog (and likely Lizardman and similar cryptids too). Here are but a few of the Squamozoic’s many denizens. Image: Darren Naish.

Our conclusion that some mystery creatures encountered on Earth are actually travellers from parallel dimensions was unashamedly inspired by promotion of the same idea, presented as a serious possibility in some of the mystery animal literature (Keel 1975, Bord & Bord 1980) and clearly not contradicted by our understanding of the way reality works.

Caption: the Bords were surely right, and John Keel was too.

On that note, The Cryptozoologicon Volume 2 will appear one day, we promise.

For previous TetZoo articles on the Cryptozoologicon project and on cryptozoology and mystery creatures in general, see…

Tales from the Cryptozoologicon: the Yeti, August 2013

Tales from the Cryptozoologicon: Megalodon!, August 2013

The Cryptozoologicon (Volume I): here, at last, December 2013

If Bigfoot Were Real, June 2016

Bigfoot’s Genitals: What Do We Know?, August 2018

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent, November 2019

Refs - -

Bord, J. & Bord, C. 1980. Alien Animals. Granada, London.

Bord, J. & Bord, C. 1989. Modern Mysteries of the World. Guild Publishing, London.

Coleman, L. 1995. Jersey Devil walks again. Fortean Times 83, 49.

Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M. & Naish, D. 2013. Cryptozoologicon Volume I. Irregular Books.

Geist, V. 1999. Deer of the World. Swan Hill Press. Shrewsbury.

Haupt, R. 2015. The Loveland Frog. Skeptoid Podcast. Skeptoid Media, 30 Jun 2015. Web. 11 Jan 2020.

Keel, J. 1975. Strange Creatures from Time & Space. Nevill Spearman, London.

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent

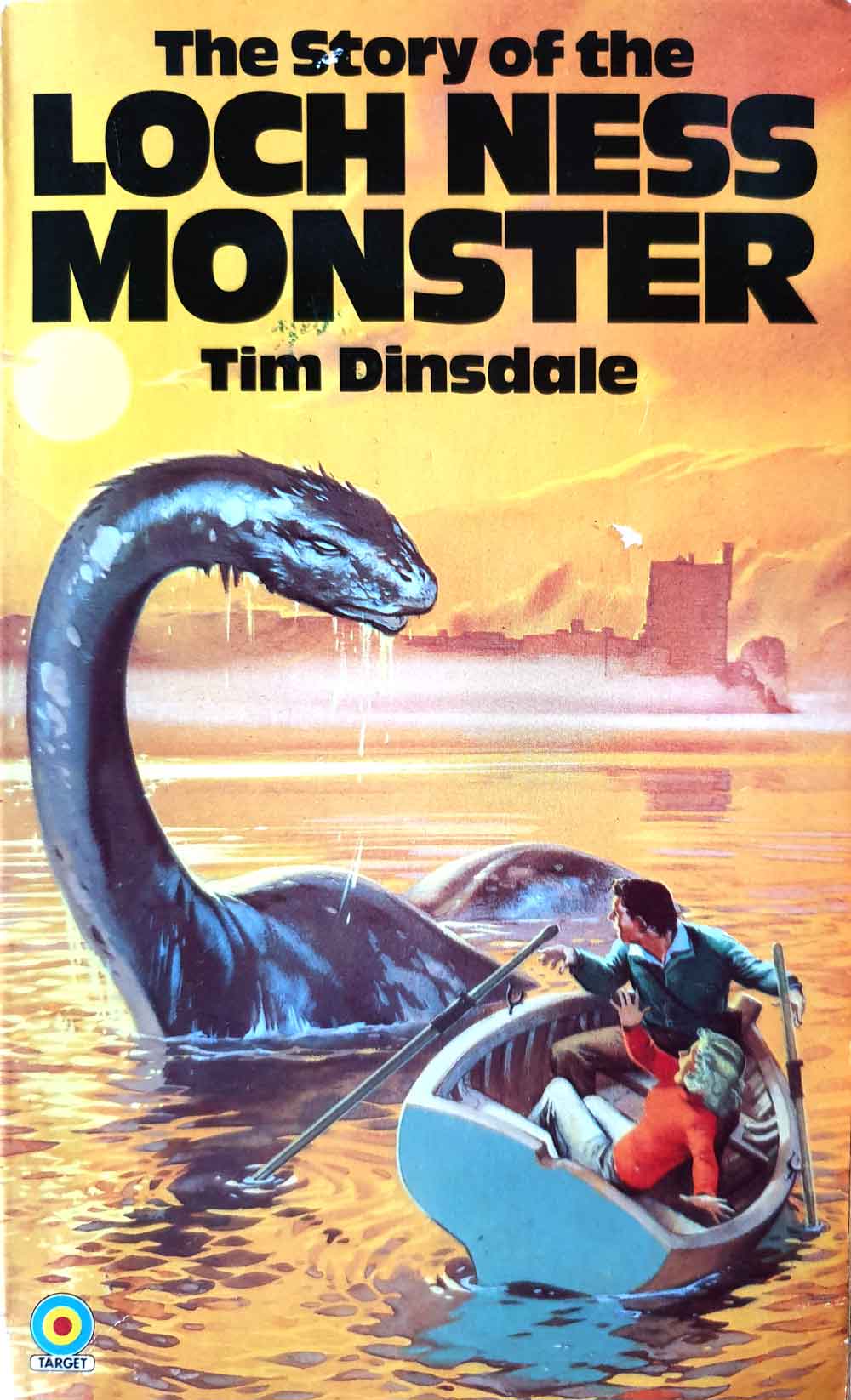

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 3: The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness

The story of the Loch Ness Monster is not a zoological one, no matter how desperately those who support the alleged existence of the monster wish it were. It is, instead, the story of people. Of people who tricked others into thinking that they saw or believed in a monster, of people who really thought they had seen a monster, and of people who wrote about, and theorised about, the thoughts, beliefs and adventures of others who’d thought or claimed they’d seen a monster.

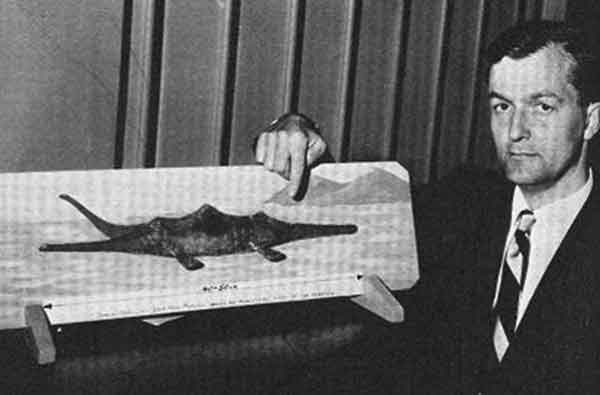

Caption: Tim Dinsdale with his own reconstruction of the Loch Ness Monster (a clay model, held in place on a painted wooden board). I presume this photo was taken on the set of the BBC Panorama studio. Image: (c) Tim Dinsdale.

One of the most important characters as goes popularisation of the monster and promotion of its ostensible reality remains aeronautical engineer Tim Dinsdale (1924-1987). Over the three decades in which he was involved in the Loch Ness Monster story, he wrote four Nessie-themed books (Dinsdale 1961, 1966, 1973, 1975; not counting later editions), produced the text for a map (Dinsdale 1977), procured what remains the most famous piece of Nessie-based camera footage, and was deeply and closely involved in several campaigns and schemes to have the Loch Ness Monster formally recognised as a genuine animal species deserving legal protection.

Caption: covers of Dinsdale’s Loch Ness books - though not depicting all editions. Image: Darren Naish.

Those familiar with Dinsdale’s writings will already know the basics as goes his involvement in the Nessie saga. However, a lengthy work dedicated to his life and adventures was always needed, and I’m pleased to say that this gap in the literature was filled in 2013 by Angus Dinsdale’s The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness (A. Dinsdale 2013). This second Dinsdale is Tim Dinsdale’s son, who has written an affectionate but never overly sentimental review of his father’s life.

Caption: cover of A. Dinsdale’s 2013 book The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness.

My review here is the third and final part of the connected series on recently published books about the Loch Ness Monster (the other parts are here and here), though rest assured that it certainly won’t be the last thing I say on the subject since there are several other recently published works that warrant review as well (Ronald Binn’s 2019 The Decline of the Loch Ness Monster will likely be next). I appreciate that it might seem a bit odd to review a book published more than six years ago, but better late than never.

Caption: Dinsdale’s 1977 map is meant to be about Loch Ness in general. It is, of course, quite heavy on monster promotion (Dinsdale 1977). Image: Darren Naish.

The Man Who Filmed Nessie begins with several biographical chapters on Tim Dinsdale’s family background and early adult life. It is partly autobiographical, discussing the Dinsdale adventure as seen through the eyes of his son, but also includes long quoted sections from Dinsdale’s writings. In the text that follows, any mention of or reference to ‘Dinsdale’ should be assumed to refer to Tim Dinsdale, not Angus.

The story of how Dinsdale became seduced by the allure of the Loch Ness Monster is familiar to those who’ve read his books (Dinsdale 1961, 1975) and those written about him (e.g., Witchell 1975, Binns 1983, 2017, Campbell 1986, Williams 2015). For a level-headed person with a ‘practical’ background as an engineer, it’s remarkable how quickly Dinsdale became essentially convinced by the monster’s reality. This revelation wasn’t achieved after a personal encounter with the beast, nor after he’d spoken to some number of sincere witnesses. No: he read a single article in a popular magazine (Everybody’s magazine), titled ‘The Day I Saw the Loch Ness Monster’ (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 42).

Caption: Dinsdale’s identikit rendition of what the Loch Ness Monster must look like, reconstructed by taking averages from the various eyewitness encounters he’d read. Image: Dinsdale (1960).

Inspired and excited, he decided that he had to go to Scotland to see the beast for himself, so off he went. Aaaand… immediately saw Nessie! Yes, on the very first day of his arrival at Loch Ness (16th April 1960), Dinsdale thought that he’d seen Nessie. It turned out to be a floating tree trunk (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 51). On 21st April 1960 (the fourth day of his scheduled expedition at the loch) – shortly after spending time with water bailiff and Nessie oracle Alex Campbell – he again saw, and this time filmed, Nessie: “a churning ring of rough water, centring about what appeared to be two long black shadows, or shapes, rising and falling in the water!” (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 62). And on the final and sixth day of his expedition (23rd April 1960) he again saw and filmed Nessie, this time procuring the famous Foyers Bay footage, featuring a humped object – Dinsdale likened it to the “back of an African buffalo” – moving across the loch. After obtaining control footage of a boat (albeit at a different time of day, in different lighting conditions, and with a white-hulled boat obviously different from the mahogany ‘monster’), Dinsdale immediately messaged the British Museum, his reasoning being that the leading zoological institution of the country should hear about it first. After having the film developed, he waited, honestly expecting an excited cadre of professional biologists to beat a path to his door. After about seven weeks of silence, he gave up waiting and went to the press, his ultimately successful plan being to have the footage screened on the flagship BBC news programme Panorama.

Caption: a screengrab from the approximately 1 minute long Dinsdale film of April 1960. The dark object was thought by Dinsdale to be the mahogany brown, ‘peaked’ back of a massive aquatic animal. Image: (c) Tim Dinsdale.

He brought along a clay monster model he had made, the fact that it had been kitted out with three humps now appearing inconsistent with the monster shown in the footage. Alex Campbell also featured on the same TV show. To Dinsdale’s eyes, the Panorama experience was not merely crucial as goes the promotion of his case, but valuable in the scientific sense since the “increase in definition and contrast” made to the film by the TV people improved its clarity and shed additional information on the appearance of the Loch Ness animal.

Caption: a key character in the Loch Ness saga is water bailiff and journalist Alex Campbell. While at Fort Augustus, I got to see his waterside home, Inverawe. It’s the building at far right here. Dinsdale spent time with Campbell immediately before seeing and filming his ‘monster’ of April 1960. Image: Darren Naish.

Our view of Dinsdale’s film today is that it isn’t impressive and almost certainly doesn’t depict a monster. There were surely viewers at the time who must have been equally unimpressed and Dinsdale’s view that the scientists and specialists who viewed the film in secrecy displayed nothing but apathy (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 73) is, of course, a biased take since he simply expected them to agree with his interpretation. The object he filmed was no giant unknown aquatic animal, but a boat (Binns 1983, Campbell 1986, Harmsworth 2010, Naish 2017; and see Dick Raynor’s page on the footage here).

Caption: Loch Ness is often a beautiful and serene body of water, but I can’t help feeling that it must seem remote and lonely at times of the year. This photo was taken in the Spring of 2016. Image: Darren Naish.

Prior to reading this book, my feelings about Tim Dinsdale were tempered by the fact that I thought him odd for abandoning his family for long stretches while engaging in the esoteric pursuit of an alleged mystery beast in a part of the country far from home. Furthermore, my idiosyncrasies mean that I’m automatically jealous or resentful of anyone who gets to engage in an expensive hobby at what appears to be infinite leisure.

Caption: few people seriously interested in the Loch Ness Monster can claim to have spent as much time on, or close to, the waters of the loch as Dinsdale did. But many people familiar with Dinsdale’s writings have sought to follow his footsteps, at least in part. Image: Darren Naish.

It turns out that none of these things are true. Dinsdale’s monster-hunting came at great personal expense and involved some degree of hardship. Furthermore, he deliberately included his family in his monster-hunting expeditions. I particularly liked Angus’s description of the childhood tradition in which he would procure the largest available carrot from the supermarket; this was to accompany his father on an expedition, the plan being that it would be fed to Nessie once she and Angus’s dad had made friends (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 86). Whatever Dinsdale’s legacy, the lives of his children were surely enriched by their regular trips to Scotland and their involvement in something as unusual as the pursuit of the Loch Ness Monster, though I have to admit that my personal circumstances while reading this book – I was working in China and missing my family – probably influenced my sentimental feelings on this issue.

Caption: you’ve probably read that the water of Loch Ness is tea-coloured. This is what it looks like when the bottom is less than 1 m away. Get to a depth of 10 m, and there’s essentially no light and nothing but darkness - at least, as far as the human eye is concerned. Image: Darren Naish.

While monster hunting, Dinsdale occasionally checked the shoreline. He was aware of the land sightings of Nessie and kept in mind the possibility that he might see the beast on land himself. I should mention here that refractory Nessie fan and blogger Roland Watson has recently published an entire book on the subject of land sightings, titled When Monsters Come Ashore. It’s written in extremely large font and in the bombastic and childish style characteristic of True Believers and is surely not a fair continuation of the level-headed and restrained, respectful tone of Dinsdale’s writings. In other words, poor Tim would not be happy with the state of Nessie promotion occurring among those few who might consider themselves his modern disciples.

One of the most interesting sections of the Nessie story concerns the arrival of the Americans and the use of assorted high-end bits of mechanical and photographic kit. While it might have seemed that Dinsdale and other British Nessie-hunters could have been gradually edged out of the quest, Robert Rines and his colleagues were on good terms with Dinsdale and even helped win him a lecture tour of the US, and ultimately to appear on big-hitting TV shows like The David Frost Show and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (A. Dinsdale 2013).

Caption: a Loch Ness scene, fortuitously featuring a waterbird (in this case, a Mute swan Cygnus olor) and a boat. Both objects have undoubtedly contributed in no small part to the phenomenon known as the Loch Ness Monster. Image: Darren Naish.

Indeed, Dinsdale’s fame reached its peak during the early and mid 1970s, as did the quest for Nessie in general. The mounting excitement that something was surely there and due to be confirmed – a belief fuelled by all that fancy American technology – inspired the idea that Nessie-like animals might lurk in other, nearby bodies of water. The book recounts Dinsdale’s expedition to Loch Morar, a place very different from Loch Ness but also said to have its own monster, called Morag. The main point of interest here to monster nerds is that the Dinsdales happen to meet a Mrs Parks, sister to one of two men who claimed a close Morag encounter.

Caption: Dinsdale was never explicit about the zoological identity he favoured for the Loch Ness Monster, but he clearly favoured the idea that it was a living plesiosaur, albeit one that had undergone a fair amount of change since the end of the Cretaceous. The legend of the late-surviving plesiosaur - reflected in this model, made for a TV show and photographed at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in 2005 - owes something to Dinsdale’s writing. Image: Darren Naish.

The story – recounted in several monster books – is famous because the two men (Duncan McDonell and William Simpson) apparently had to use an oar to fend Morag away from their boat, and so vigorous was the interaction that the oar snapped. The story usually ends there. Another Nessie-themed book, however, explains how the individuals concerned had been poaching deer and were trying to discard an unwanted skin which, despite being filled with stones, refused to sink. Eventually it had to be whacked with an oar, and here we find what is claimed to be the actual explanation for the oar-breaking event (Harmsworth 2010, p. 218).

Caption: the ‘two people in a lake come so close to a monster that they have to hit it with an oar’ trope has been taken seriously enough to inspire this re-enactment, this time involving the Lake Storsjö monster of Sweden. The man with the oar is Ragner Björks. Image: Bord & Bord (1980).

In places, Dinsdale’s story arc is a melancholy one. He wrote of his realisation, years after his initial forays in boats on Loch Ness, that he had become an experienced and confident boatman, his long, quiet stretches involving grey water, and rain. He never was to experience anything again as thrilling as his 1960 filming of the ‘monster’s hump’, nor did this footage receive the accolade he hoped it would. The decline and demise of the Loch Ness Investigation Bureau during the early 1970s marked “the end of an era” (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 200), and even the 1975 scientific symposium – the high water mark of Nessie’s scientific respectability, convened to discuss the sonar traces and photos obtained by Rines and his colleagues – was regarded as a disappointment (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 217). As scientific interest in Nessie waned during the 1980s, Dinsdale complained in 1987 that scepticism had taken over, that “Nessie in the 80s has, if anything, been going backwards” (Williams 2015, p. 202). A planned sequel to 1975’s Project Water Horse, intriguingly titled Loch Ness and the Water Unicorn, and said in the 1982 edition of Loch Ness Monster to be partly written, never appeared in print (Binns 2019).

Caption: scientific interest in Nessie might have waned during the 1980s, but this was the decade that gave us this fantastic book cover. You might doubt that encounters as close and thrilling as this ever occurred. It belongs to the sixth edition of this book, published in 1982.

Some authors, especially those championing the Loch Ness Monster’s existence, have framed Tim Dinsdale as the most brilliant, wise and relevant authority on the Loch Ness Monster (pro-Nessie author Henry Bauer is an example). It’s easy to be convinced from Dinsdale’s writings, and his son’s, that he was indeed sincere, honest, and trying as best he might to stir scientific and mainstream interest in something that he regarded as unquestionably real. And his underlying methodology was scientific. But he seemed never to grasp why the official response was one of apparent disinterest and apathy. It wasn’t down to “stubbornness … indifference … [and] arrogance” (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 232), but to the fact that the evidence just wasn’t good enough, and that there never was a good reason to believe in a monster. That Dinsdale became almost fixated on the monster’s existence after reading a single popular magazine article does not – I have to say it, forgive me – seem consistent with someone who might be deemed wise, level-headed and of the most sceptical, rational approach.

Caption: the Peter O’Connor photo of 1960 - this is a low-res, cropped version - has appeared several times at TetZoo over the years and is almost certainly a hoax, most likely an overturned kayak and a model head and neck (Naish 2017). Dinsdale included it in early editions of his book Loch Ness Monster but it - and any accompanying prose devoted by Mr O’Connor - is absent from the fourth edition and those that appeared afterwards. Image (c) Peter O’Connor.

On that note, and while it again shames me to say it, I’m impressed – if that’s the right word – by Dinsdale’s naivety when we look at specific parts of his Loch Ness experience. Take his interaction with Tony Shiels, the self-proclaimed Wizard of the Western World. In 1977 Shiels claimed to capture on film the most remarkable colour photos of Nessie ever taken, an object affectionately known today as the Loch Ness Muppet. Any familiarity with Shiels and his adventures quickly reveals that he has, and seemingly always has had, a tongue-in-cheek, jovial take on monsters and how they might be seen. They’re not really meant to be undiscovered animals lurking in remote places, but interactive pieces of quasi-surreal art akin to open-air theatre, the ensuing cultural response in literature and news being as much a part of the event, if not more, as the claimed sighting and photo. While I undoubtedly write with the benefit of hindsight (and, dare I say it, some quantity of insider information), Dinsdale was seemingly unable to perceive this. And thus the muppet photo appears – as a legit image of the Loch Ness animal – on the cover of the fourth edition of Dinsdale’s The Loch Ness Monster, a decision that speaks volumes.

Caption: the infamous 1977 Shiels muppet photo. Exactly what it depicts (a plasticine model superimposed on a scene showing water? A floating model posed in the loch?) remains uncertain. Image: (c) Tony Shiels.

The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness is an essential read for those seriously interested in the history of monster searching and the people who engage in it. The book has very high production values and impressive design and editorial standards, and includes an excellent colour plate section. I enjoyed reading it and think that Angus Dinsdale has produced a book that his late father would have been proud of, and moved by. Many interesting people have contributed to the lore of the Loch Ness Monster, and Dinsdale was without doubt one of the most important and influential. I leave you to judge whether this was time wasted, or a life enriched and made remarkable.

Dinsdale, A. 2013. The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness. Hancock House, Surrey, BC Canada. pp. 256. ISBN 978-0-88839-727-0. Softback, refs, index. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

Nessie and related issues have been covered on TetZoo a fair bit before, though many of the older images now lack ALL of the many images they originally included…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013 (now stripped of all images, so completely useless)

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014 (now stripped of all images)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Refs - -

Binns, R. 1983. The Loch Ness Mystery Solved. Open Books, London.

Binns, R. 2017. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. Zoilus Press.

Binns, R. 2019. Decline and Fall of the Loch Ness Monster. Zoilus Press.

Bord, J. & Bord, C. 1980. Alien Animals. Granada, London.

Campbell, S. 1986. The Loch Ness Monster: the Evidence. The Aquarian Press, Wellingborough, UK.

Dinsdale, T. 1961. Loch Ness Monster. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Dinsdale, T. 1966. The Leviathans. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Dinsdale, T. 1973. The Story of the Loch Ness Monster. Target, London.

Dinsdale, T. 1977. The Facts About Loch Ness and the Monster. John Barthlomew & Sons, Edinburgh.

Harmsworth, T. 2010. Loch Ness, Nessie and Me. Harmsworth.net, Drumnadrochit.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Williams, G. 2015. A Monstrous Commotion: the Mysteries of Loch Ness. Orion Books, London.

Witchell, N. 1975. The Loch Ness Story. Penguins Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.