The fossil record is a cruel and fickle mistress, and there are a vast many fossil animals for which key data on lifestyle and biology is simply not preserved, or – at least – not known. Yet…

Azhdarchid Progress, a Personal View

The Quetz Monograph Lives and Other News on Azhdarchid Pterosaurs

Baby Pterosaurs Were Excellent Fliers and Occupied Different Niches From Their Parents

New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology, the TetZoo Review

Why the World Has to Ignore David Peters and ReptileEvolution.com

Did Dinosaurs and Pterosaurs 'Glow'? Extinct Archosaurs and the Capacity for Photoluminescent Visual Displays

One of many exciting discoveries made in tetrapod biology in recent decades is that UV-sensitive vision is not just a thing that exists, but a thing that’s widespread.

Caption: would a live dinosaur - like this heterodontosaur - look utterly different if its tissues were photoluminescent? Brian Engh explored this possibility in this excellent piece of art, included in Woodruff et al. (2020). Image: Brian Engh.

We’ve known since the early 1980s that at least some birds can detect UV wavelengths, and research published more recently has demonstrated its presence in lizards of disparate lineages, in turtles, rodents and, most recently, amphibians. Some of these animals use their UV-sensitive vision to find food (like pollen-rich flowers) and perhaps even to navigate their environments (UV-sensitive vision in certain forest-dwelling birds might enhance their ability to see certain kinds of leaves, for example).

That’s great, but what’s even more surprising – though maybe it shouldn’t be – is that markings and tissue types in some of these animals are visible to other animals with UV-sensitive vision. Furthermore, some tissue types are able to absorb UV and re-emit it within part of the spectrum visible to we humans. It’s this aspect of the UV story – the possibility that UV is absorbed and emitted as visible light (typically blue light) – that we’re talking about hereon, not UV-sensitive vision. Note that the terms used for this phenomenon are slightly contentious among relevant experts. Most agree that the right term is fluorescence whereas others (including my colleague Jamie Dunning) argue that we should use the more specific photoluminescence. I have no proverbial dog in this fight but am going to stick with photoluminescence here seeing as it’s the one we used in the relevant paper.

Caption: in 2018, Jamie Dunning and colleagues reported the discovery of photoluminescence in puffins. Image: (c) Jamie Dunning.

The discovery of photoluminescence in animals is evidently of broad general interest, and I can make this assertion because several recent studies reporting its occurrence have received an unusual amount of public interest. Dunning et al.’s (2018) report on its occurrence in the brightly coloured bill plates of puffins, for example, proved a really popular discovery (Wikinson et al. (2019) followed up with a subsequent study on the keratinous horns of rhinoceros auklets), as did Prötzel et al.’s (2018) discovery of photoluminescent bones in chameleons. Remarkably, Prötzel et al. (2018) were able to show that the ‘glowing’ bones of these lizards are visible through the skin. At the time of writing, a study reporting widespread photoluminescence in living amphibians has just appeared, and it too has received a fair amount of general interest.

Here it’s worth making a critical point on the popularity of these studies in the popular media. There’s no doubt that this stuff is interesting, and certainly of relevance to biologists at large (for one thing, knowing about the distribution of fluorescence/photoluminescence could have all kinds of implications for surveying and collecting). But there’s concern that the studies are being framed in the wrong way, and that more thorough vetting is needed, in places. Also worth noting is that what role photoluminescence actually has to the animals that emit it is controversial, since some workers argue (a) that its visual signalling role hasn’t been sufficiently tested for, and (b) it may simply be too subtle to be of much use to the animals in which it’s present. Keep this in mind when reading the following!

Caption: Prötzel et al.’s (2018) bone-glow research on chameleons shows that the photoluminescing bones of these lizards were actually visible through the skin. Image: David Prötzel.

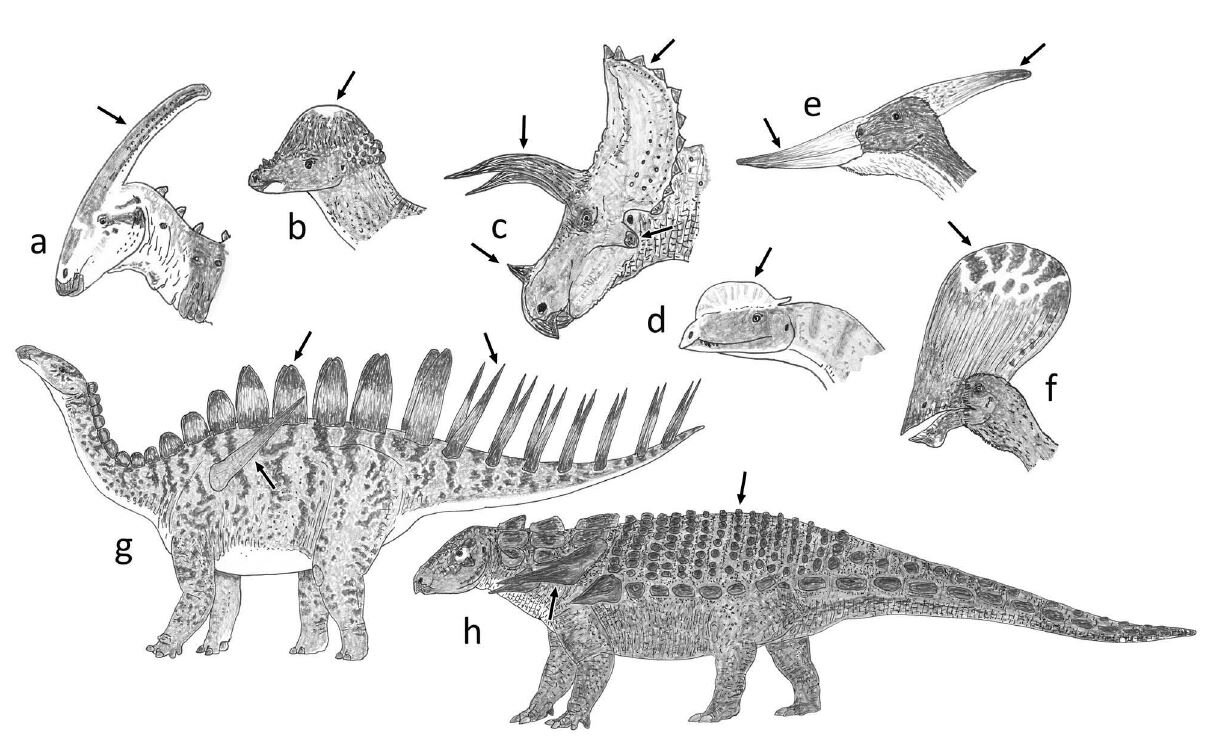

These caveats notwithstanding, if UV-themed visual displays are widespread in tetrapods, those of us interested in fossil animals are presented with an interesting set of possibilities. We already think that the many extravagant structures of non-bird dinosaurs and pterosaurs – they include cranial horns, crests and casques as well as spikes, spines, sails, bony plates and so on – functioned predominantly in visual display. Could they also have been photoluminescent, and could this have then been used to enhance the display function of the structures in question?

Caption: dinosaurs and pterosaurs are of course notable for their remarkable variety of what I term extravagant structures, a selection of which are depicted here. (a) Parasaurolophus, a hadrosaurid ornithopod. (b) Pachycephalosaurus. (c) Triceratops, a ceratopsid ceratopsian. (d) Dilophosaurus, a theropod. (e) Pteranodon and (f) Tupandactylus the pterodactyloid pterosaurs. (g) Miragaia the stegosaur. (h) Edmontonia the nodosaurid ankylosaur. From Woodruff et al. (2020), images by Darren Naish.

In a brand-new paper published this week in Historical Biology (or on its website, anyway), Cary Woodruff, Jamie Dunning and I set out to consider this very question (Woodruff et al. 2020). At the risk of spoiling the surprise I’ll say that we don’t provide a hard or definitive answer; our aim instead is to bring attention to the possibility that photoluminescence might have been present in some of these animals. We encourage the testing of this possibility and suggest some specific ways in which this testing might be performed. Of incidental interest is that our collaboration evolved from a Twitter discussion (which is currently findable here).

Caption: a palaeontologist ponders new papers on photoluminescence, and then gets talking to one of the relevant researchers. And I chimed in as well, sorry. The rest is history…

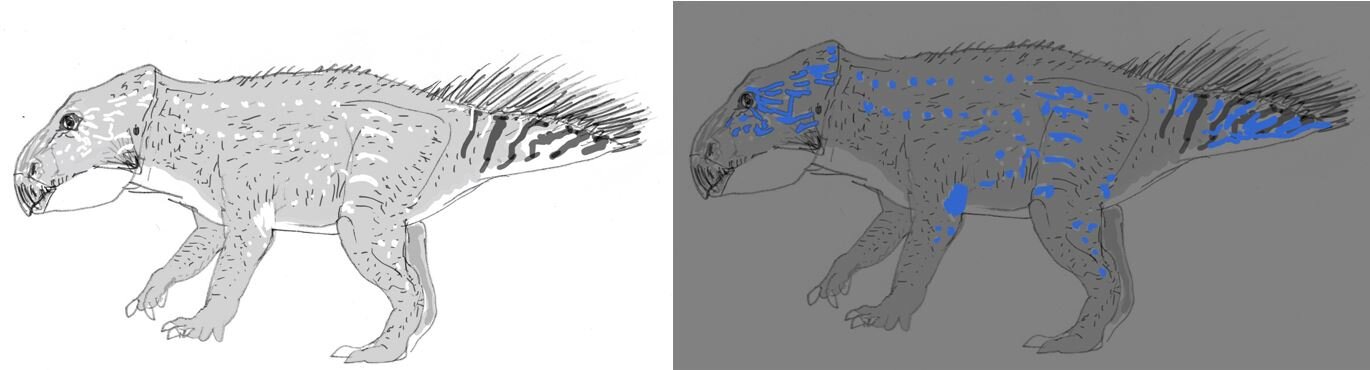

I should also add that our idea isn’t especially new. Ever since UV-sensitive vision was first reported in birds back in the 1980s, the idea that extinct dinosaurs might have made use of photoluminescence has been mooted (though, let me make the point again: you don’t need UV-sensitive vision to see photoluminescence). I’ve incorporated photoluminescence into more than one dinosaur-themed media project, most recently Dinosaurs in the Wild.

Caption: the idea that Mesozoic dinosaurs might have been exploiting photoluminescence isn’t altogether new. Here are rough sketches I produced depicting the concept of a photoluminescent Leptoceratops produced for the travelling visitor experience Dinosaurs in the Wild. Image: Darren Naish.

A few specific points are worthy of attention. Above, I mentioned Prötzel et al.’s (2018) chameleon-themed ‘bone glow’ study. Bone-based photoluminescence has also been reported in frogs, specifically in the Brachycephalus pumpkin toadlets (Gouette et al. 2019). Could those dinosaurs superficially similar to chameleons (namely ceratopsians: like some chameleons, they have bony frills and prominent horns) also possess bone-based photoluminescence and, if so, could they exploit it in chameleon-like fashion? Well, probably not, mostly because the much larger size of these dinosaurs means that their skin was too thick for this to work (Woodruff et al. 2020).

Caption: for fun, let’s use toy ceratopsians rather than the real things. Could these dinosaurs have had ‘glowing’ bones as modern chameleons do? No, almost certainly not. Image: Darren Naish.

One of the most unusual things about non-bird dinosaurs possessing extravagant structures is that males and females are extremely similar (albeit not necessarily identical) with respect to the form and proportional size of said structures. As regular TetZoo readers might recall from several articles published here within recent years (see links below), some workers interpret the extravagant structures of Mesozoic dinosaurs as functioning within a model of species recognition. According to this model, the structures function as banners used to signal membership of whatever the respective species is. I don’t think that this is valid for a bunch of reasons and in fact I don’t think that extravagant structures have an important role in species recognition at all (Hone & Naish 2013, Knell et al. 2013). An alternative model posits that extravagant structures mostly have an intraspecific function, work as sociosexual signals of reproductive quality, and evolved within the context of sexual selection. This is the model that I and my colleagues support (Hone et al. 2011, Knell et al. 2012, 2013, Hone & Naish 2013), and a lengthy debate that’s been thrashed out in the literature over the past decade pits species recognition and sexual selection as opposing schools of thought.

Caption: at left, mutual sexual selection at play in the Great crested grebe, as illustrated by Julian Huxley in 1914. At right, cover of the famous issue of TREE which includes Knell et al.’s (2012) seminal review.

But if this is so, why is it that ostensible males and females in the dinosaur species concerned are monomorphic: that is, they have similar extravagant structures? Back in 2011, Dave Hone, Innes Cuthill and I argued that these animals might have evolved their extravagant structures within the context of mutual sexual selection (Hone et al. 2011), this being the strategy where both males and females use their extravagant structures in sociosexual display. But while we know that extant monomorphic animals really are monomorphic, we’re not sure that this is (or was) the case for extinct ones: it could still be that their structures differed in hue, colour or some other visual property. If we’re speculating about the possible presence of photoluminescence in extinct archosaurs, the possibility exists that “monomorphic elaborate structures in pterosaurs and non-bird dinosaurs were not monomorphic in life” but differed in how they photoluminesced (Woodruff et al. 2020, p. 5). We were inspired by the sexually dimorphic photoluminescence of chameleons and Brachycephalus frogs.

Caption: could the in-situ, fully intact armour of ankylosaurs like that of the amazing holotype of Borealopelta, shown here, give insight into the potential of photoluminescence in these animals? Image: CC SA 4.0, original here.

Finally… speculating about the presence of photoluminescence is all very well and good, but can we test for it? In those cases where part of the integument is preserved, we can, by shining blacklights at the respective specimens. The problem, however, is that we might not be seeing the original light-emitting properties of the animal. Seemingly positive results might be a consequence of the fact that various tissues (bone included), minerals and preservatives fluoresce under UV (Woodruff et al. 2020).

As a preliminary test, we looked at the osteoderms of the spectacularly preserved ankylosaurs Borealopelta and Zuul under UV light… we did get results, but it’s difficult to know what, if anything, these results tell us about any condition present in life (Woodruff et al. 2020). I should add that people have been shining blacklights at fossils for a long time and seeing all kinds of interesting results (hat-tip to the pioneering work of Helmut Tischlinger); in no way are we implying that we’re anything like the first to do this.

Caption: people have been examining fossils with UV light for decades. These images show the Jurassic pterosaur Bellubrunnus roethgaengeri, illuminated via the use of UV. Image: Hone et al. 2012 (original here).

And that about wraps things up for now. As will be clear, our paper is not much more than a preliminary set of speculations and suggestions for further work, and isn’t intended to be an in-depth analysis of the proposal. But – as I see it – that’s ok: the scientific literature really shouldn’t be considered focused on results alone, since review, discussion and valid speculation are valuable and worthy too. I hope you agree.

UPDATE (adding 4th March 2020): this article has been somewhat modified relative to its original version, since a misunderstanding on my part meant that I was previously describing photoluminescence as a phenomenon especially relevant to animals with UV-sensitive vision. Substantial thanks to Michael Bok for his interest and assistance and for sending comments which enabled me to modify the article.

For previous TetZoo articles on the biology and life appearance of Mesozoic dinosaurs and pterosaurs, see (as usual now, linking to wayback machine versions due to vandalism and paywalling of ver 2 and 3)…

Zuniceratops and the early acquisition and alleged dimorphism of ceratopsian brow horns, April 2009

Necks for sex? No thank you, we’re sauropod dinosaurs, May 2011

Did dinosaurs and pterosaurs practise mutual sexual selection?, January 2012

Sexual selection in the fossil record, September 2012

Dinosaurs and their ‘exaggerated structures’: species recognition aids, or sexual display devices?, April 2013

Refs - -

Dunning, J., Diamond, A. W., Christmas, S. E., Cole, E. L., Holberton, R. L., Jackson, H. J., Kelly, K. G., Brown, D., Rojas Rivera, I. & Hanley, D. 2018. Photoluminescence in the bill of the Atlantic Puffin Fratercula arctica. Bird Study 65 (4), 1-4.

Goutte, S., Mason, M.J., Antoniazzi, M.M., Jared, C., Merle, D., Cazes, L., Toledo, L.F., el-Hafci, H., Pallu, S., Portier, H., Schramm, S., Gueriau, P. & Thoury, M. 2019. Intense bone fluorescence reveals hidden patterns in pumpkin toadlets. Scientific Reports 9, 5388.

Prötzel, D., Heß, M., Scherz, M. D., Schwager, M., van’t Padje, A. & Glaw, F. 2018. Widespread bone-based fluorescence in chameleons. Scientific Reports 8, 698.

Wilkinson BP, Johns ME, Warzybok P. 2019. Fluorescent ornamentation in the Rhinoceros auklet Cerorhinca monocerata. Ibis 161, 694-698.

Mark Witton’s The Palaeoartist’s Handbook

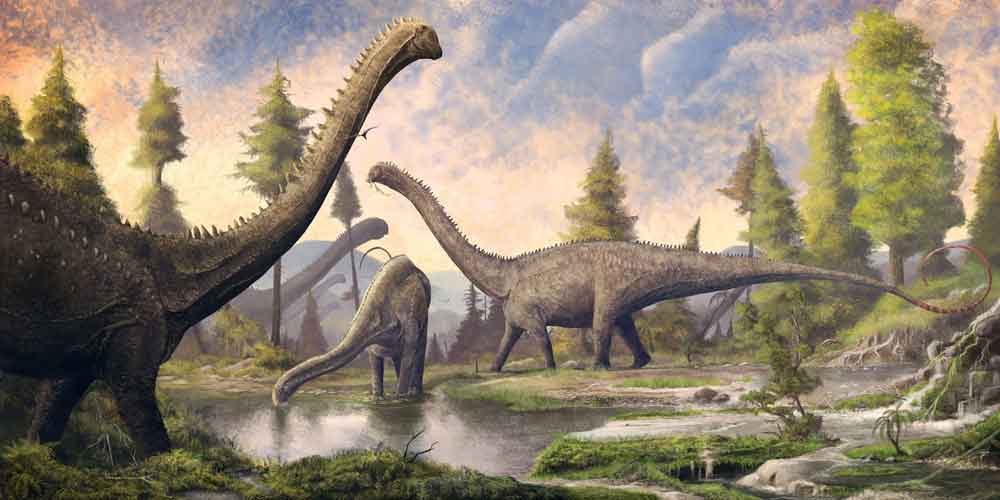

It’s probably – no, surely – true to say that palaeoart (aka paleoart) is more popular right now that it ever has been, a fact due in equal part to a vibrant, active community of people worldwide, to the instant, ubiquitous reach of the internet and the connectedness we feel via social media, to self-publishing and on-demand printing services, and to the excitement and discussion generated by what seems to be a never-ending stream of amazing fossil and anatomical discoveries relevant to ancient animals.

Caption: today, Mark Witton is well known for generating large-scale artworks like this one - depicting the sauropod Diplodocus, and produced to accompanying the NHM’s Dippy specimen as it tours the UK - in addition to work done to accompany press releases. Image: (c) Mark Witton.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Dr Mark P. Witton is, right now, one of the world’s best known and most visible of palaeoartists; his articles and artwork are abundant online, and his work appears in many contemporary published works on prehistoric life, and in various museum installations and other displays. Combine this with the fact that he’s published a long-sought holy grail of the palaeoart canon – a palaeoart handbook – and we surely have one of the most important and worthy palaeoart-themed volumes of all time. Right? Does it deliver?

I refer to 2018’s The Palaeoartist’s Handbook, a slick, extremely affordable softback of 224 pages and extremely high production values. In response to my question above: yes, this book does deliver, and functions extremely well as a ‘handbook’ for those interested in producing palaeoart. Buy it right now if you haven’t done so already. Even those not needing or interested in Dr Witton’s advice should obtain it if they’re interested in palaeoart, since it contains stacks of invaluable review and commentary, does a great job of stating where we are with respect to what we think we know about the appearance of ancient animals, and is really well designed and densely illustrated. It’s probably the most important volume yet published on palaeoart*, and that remains true even if you dislike or disagree with the author’s contentions.

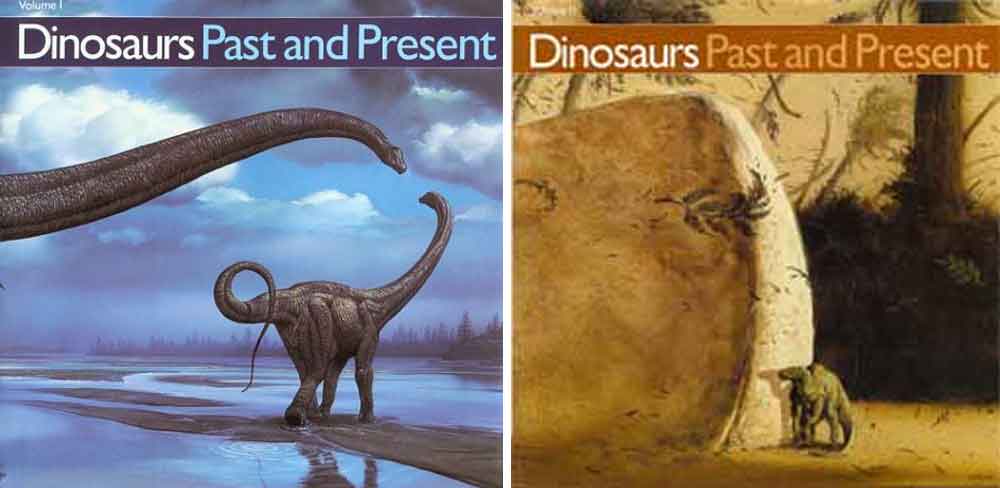

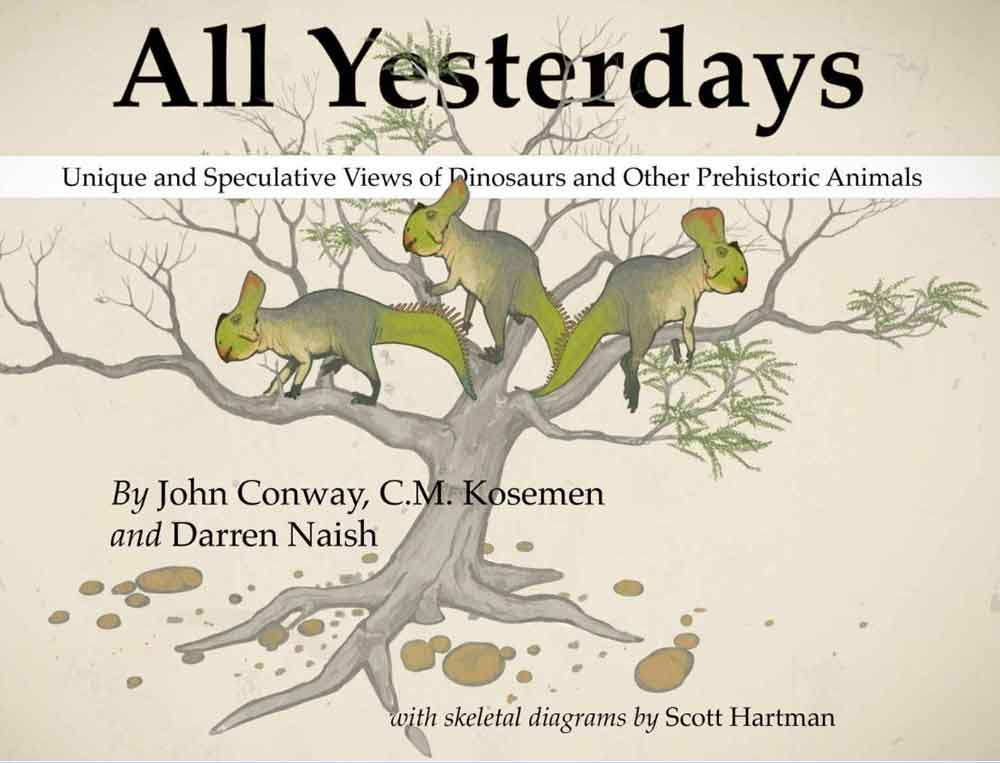

* ‘Importance’ is subjective, but the volume vies – I predict – with 2012’s All Yesterdays and volumes I and II of Dinosaurs Past and Present.

Caption: there aren’t many ‘crucial’/’must have’ volumes on palaeoart, but the Dinosaurs Past and Present volumes are among them, volume II in particular because of Greg Paul’s article (Paul 1987). Images: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press.

A disclaimer I should mention upfront is that Mark and I are long-standing friends and colleagues. I lectured to Mark when he was an undergrad, we’ve been on fieldwork together, and we’ve published several works together on pterosaurs (Witton & Naish 2008, 2015, Dyke et al. 2014, Vremir et al. 2015, Naish & Witton 2017) and palaeoart (Witton et al. 2014). These things might, in theory, mean that I’m positively biased towards his work, but in reality I think they help make me more neutral, since our good relationship means that I can say negative things (where fair and appropriate) and not be worried about being offensive. But let’s see.

Witton (2018) is extremely well designed and very attractive. It’s glossy, full colour throughout, and absolutely packed full of diagrams, photos and art. The art is not just by Mark Witton but also features images by Raven Amos, Rebecca Groom, Johan Egerkrans, Bob Nicholls, John Conway, Emily Willoughby, Julius Csotonyi and Scott Hartman. Holy crap, it’s a virtual who’s who of Early 21st Century palaeoart.

Caption: Witton (2018) includes artwork by several artists, sometimes included to depict diverse styles, compositions and approaches. This is ‘Nemegt Sunrise’ by the amazing Raven Amos (website here), and depicts the oviraptorosaur Conchoraptor with a hermit crab. Image: (c) R. Amos.

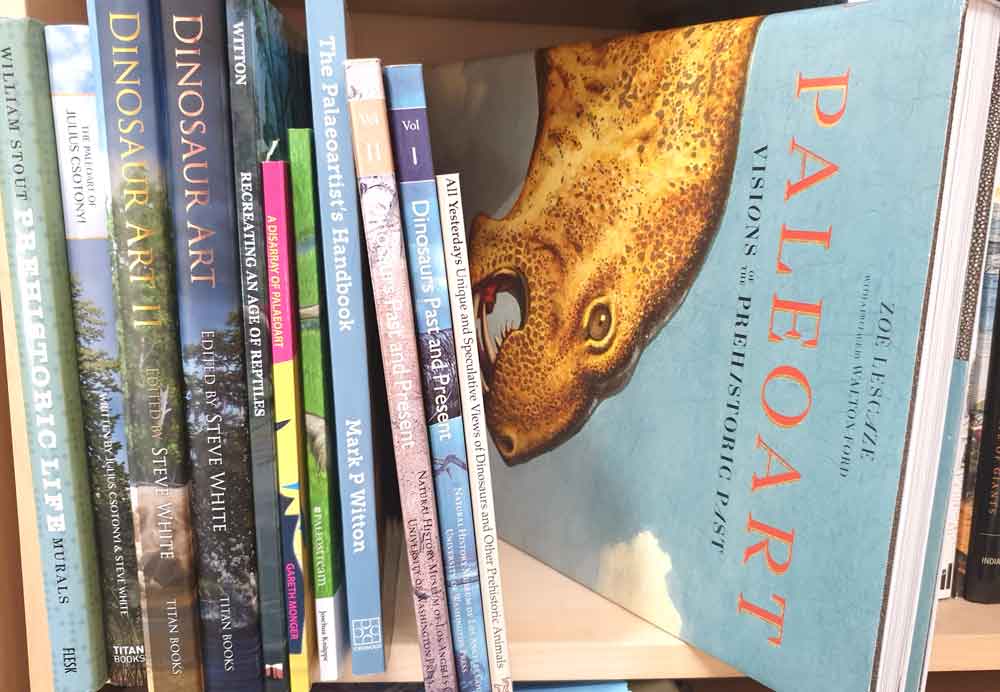

What sort of book is this? A ‘palaeoart book’ can be one of several things. It could be a compendium of historical images (like Zoë Lescaze’s gigantic, deeply idiosyncratic but invaluable 2017 Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past), it could be a bunch of new, daring stuff that makes a point of some sort (cf All Yesterdays), it could be an artist’s porfoilio or a series of portfolios (like the Dinosaur Art volumes, or The Paleoart of Julius Csotonyi), or it could be a technical volume that provides some theoretical or technical background to the field… I’m sure we’re all still waiting for ‘The Grand Handbook to Illustrating Prehistoric Life, a Rigorous How-To Guide’, hint hint.

Caption: the number of books devoted to palaeoart is growing. I think I’ve managed to keep up so far. Image: Darren Naish.

Witton (2018) is partly all of these things: the volume is fundamentally devoted to the techniques, practices and scientific processes and conventions behind the creation of palaeoart, and the case studies and targeted discussions mean that we effectively see much of Witton’s work showcased. But there’s more.

Witton (2018) begins with introductory sections on what palaeoart is and on its history. The historical chapter is quite complete and inclusive, and I’m a big fan of Witton’s take on the work of Cuvier, Hawkins at Crystal Palace and other early efforts. He’s also fair to the artists who produced work during what he terms ‘The Reformation’, some of whom (Greg Paul in particular) have had a major, lasting impact on how we imagine ancient life. The ‘palaeoart meme’ story that I’ve drawn attention to through my own research and the All Yesterdays movement bring a close to this section alongside comments on some of the amazing, exciting new developments being made in the world of soft tissues and palaeo-colour.

Caption: the Crystal Palace animals remain among the most accurate renditions of prehistoric life ever made (like all palaeoartistic reconstructions, they have to be seen as being of their time), and Mark Witton’s take on them is one I absolutely agree with. This photo of the Iguanodon pair was taken in September 2018. Image: Darren Naish.

The meat and potatoes. We then move on to the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the book: a group of chapters that discuss in great detail the process of creating palaeoart. Sections here cover how research is important and how a worker might go about doing it, how knowledge of phylogeny is integral to understanding an organism, and how artists should at least be aware of tropes and stereotypes. This book is fundamentally not a ‘rigorous how-to guide’ to all the prehistoric animals (every time I use this term I’m riffing on the title Greg Paul gave his seminal 1987 article on archosaur reconstruction), but this middle section of the book does include copious discussion of anatomy, the shapes of animals in 3D and cross-section, of musculature and posture, the importance of integument, fat and other external tissue, and so on. I should add that Chapter 9 (‘The Life Appearance of Some Fossil Animal Groups) is devoted to the probable life appearances of key tetrapod groups. Ha, take that fishes.

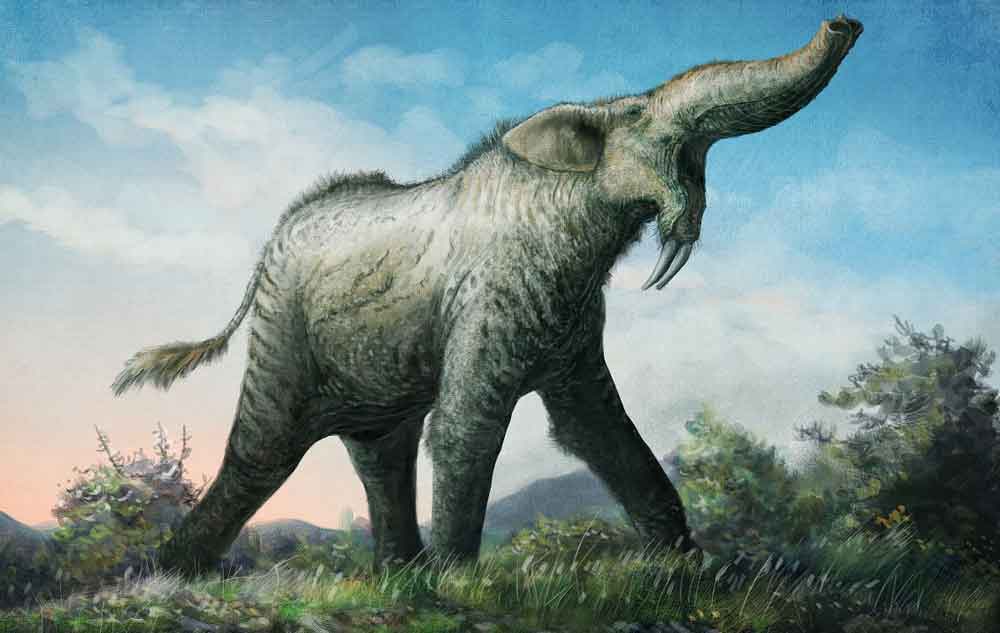

Caption: in many cases, the favoured, traditional look for a given prehistoric animal is not necessarily the one we might favour. Here’s an example: Mark has argued that a new look for the proboscidean Deinotherium - shown here - should be considered. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

These central chapters are probably the most important part of the book and will be those used most by the largest number of people. There’s a ton of information and discussion, and Mark describes in detail how he’s arrived at the conclusions he has. Readers of Mark’s blog will be familiar with some of the arguments here and might also know that much of it has never been properly published (as in, in technical papers or articles). The book is therefore especially significant as a source of primary data, though I know that efforts are underway to get at least some of it into the primary literature.

Caption: extensive sections of Witton (2018) discuss osteological correlates for external texture and other features. In some cases - like ceratopsian dinosaurs - there are many such correlates. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

How confident can we be that Mark is ‘right’ when it comes to his arguments about lips, cornified facial tissue, scalation or fuzziness on the body and so on? I think that a strong response would be that he has at least described, explained and illustrated his reasoning and it’s difficult to think that he’s ‘wrong’, two caveats being that there is – as Mark states quite clearly – still some considerable slop as goes determining the relative size of keratinous coverings (like the pads, scales and sheaths covering horns, claws and so on), and that the vagaries of taphonomy might still be cheating us out of valuable information on which archosaurs had filaments, fuzz or feathers. Yes, I still think that big tyrannosaurs could have been fuzzy and that we aren’t picking this up because the fossils concerned aren’t preserved in the ideal sedimentological regimes.

Speculation and the All Yesterdays Movement. The main message here is that while some speculation always has to be included in palaeoartistic reconstructions, there’s a lot of stuff that’s knowable, or potentially knowable, and informed by actual anatomical data. This is increasingly the case even for colour and pattern (caveat: we still only have data on some infinitesimally tiny percentage of extinct animals). The door is not open for any possibility, and artists who wish to be seen as doing work that’s scientifically credible have to take into account data derived from fossils as well as ‘rules’ (or guidelines) gleaned from living animals. However…

Caption: Conway et al.’s 2012 All Yesterdays has changed the way many people approach palaeoart… but is this for better, or for worse? Image: Conway et al. (2012).

A valid, controversial and timely point concerns just how much speculation is permissible in palaeoart. This is something I feel especially connected to given the impact of my 2012 book – co-authored with John Conway and C. M. Kosemen – All Yesterdays (Conway et al. 2012) and the subsequent ‘All Yesterdays Movement’, which is hated by some but loved by others. Mark’s take on what happened post-AY is that a lot of AY-inspired artwork has failed to appreciate the nuance of the original work, and that AY was (wrongly) taken by some as a green light to go nuts and do whatever, the results being misguided and likely wrong.

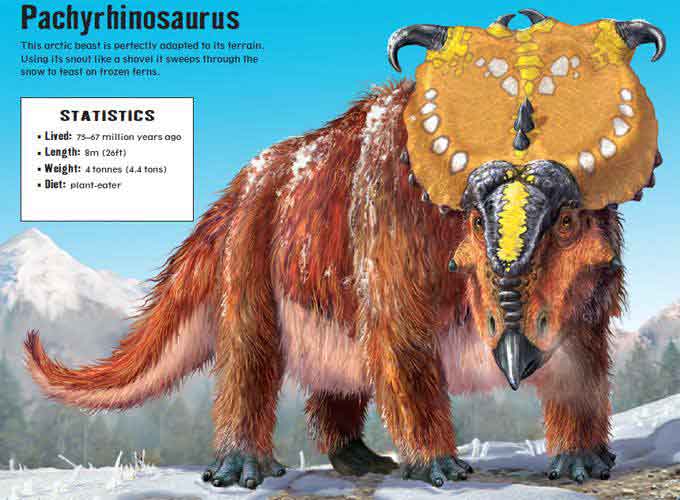

Caption: Mark has indulged in some speculation himself (here: shaggy-coated pachyrhinosaurs), and it’s down to opinion as to whether this is as extreme as anything depicted in All Yesterdays. Image: Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

Caption: it would be wrong to avoid bringing attention to Franco Tempesta’s woolly, cold-adapted pachyrhinosaur, very obviously inspired by Mark Witton’s, and appearing in the 2016 Usborne book Build Your Own DInosaurs Sticker Book. I was consultant, but I’m sure that that’s coincidental. Image: (c) Franco Tempesta/Usborne.

I agree… if we’re talking about artworks that aim to reflect possible realities. A nuance to the nuance of AY is that there exists a small contradiction in the aims of its creators. Yes, we argued that there are many potentially valid, scientifically defensible possibilities that hadn’t or haven’t been sufficiently explored in pre-AY palaeoart, but we did also promote the idea that people might explore other possibilities – even those weird or dumb or wrong – purely for the sake of artistic expression. That this view is canonical in the AYverse is demonstrated by the inclusion in the sequential All Your Yesterdays of retrosaurs that are absolutely contradicted by data but still fun from an artistic take. In other words, not all AY-inspired art is meant to be scientifically defensible. The takehome – post-AY – is that people need to say what they’re aiming to depict: a random fancy or a serious proposal?

Caption: not all AY-inspired art is meant to be scientifically responsible and potentially realistic, some of it is deliberately whimsical and fanciful. Exhibit A: the wonder that is Spinofaaras vulgaris, a creature that now has an internet life of its own. Image: (c) Chris Masna (original here).

Anyway, returning to the contents of Witton (2018), this main section wraps up with some thoughts on how landscapes are created, and how composition and mood can be formed. Discussing environments and landscapes involves science – geology, geomorphology and palaeoclimate, among other things – and this is Witton’s main strength, but I also found his take on composition, stylistic choices and other matters of artistic style compelling…. speaking as someone who lacks artistic training and expertise, that is. The volume ends with a chapter on the professional side of palaeoart.

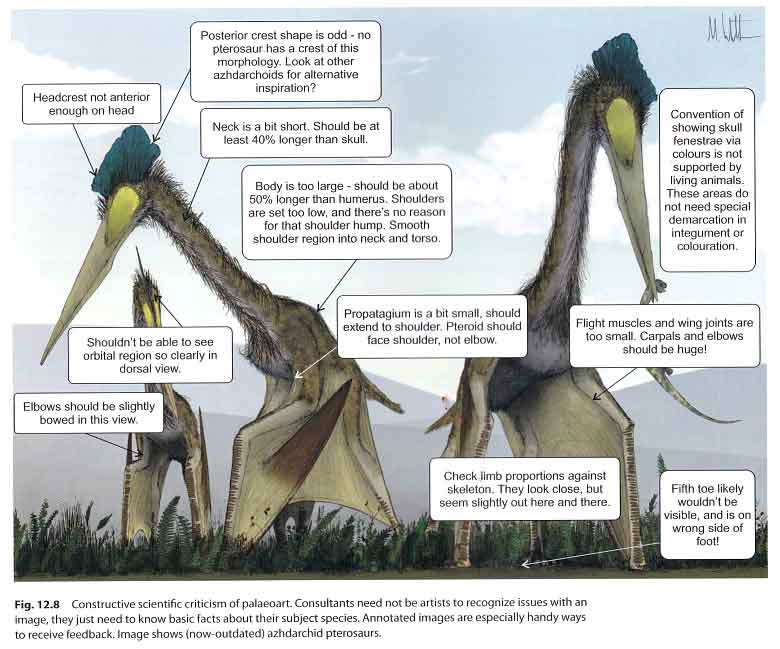

Caption: feedback and criticism is crucial, but it can be difficult to know what to say to artists when you aren’t one yourself. In this section of the book, Mark provides advice, using his 2008 azhdarchid image as a piece that might benefit from constructive criticism. This piece accompanied the Witton & Naish (2008) PLoS paper on azhdarchids. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

On the negative side of things… I find the editing sloppy in places and think that the prose could have been tightened here and there. There are also a few turns of phrase that I found awkward, weird or (sorry) terrible, top of the list being the reference to “palaeontologists with the mightiest beards” (p. 38). On technical aspects, I’m a bit confused by Mark’s use of ‘reptile’ in the old, paraphyletic sense (in a volume otherwise using modern phylogenetic nomenclature, wouldn’t it make sense to use Reptilia for the lizard + turtle + croc clade, and not to use it for a paraphyletic assemblage that excludes birds?). Panoplosaurus is wrongly called an ankylosaurid (p. 125), and isn’t Deinotherium a deinotheriid, not a deinotherid? These are minor, piffling, trivial things that I only state here because I have nowhere else to put them.

Caption: the book is just full of spectacular imagery like this, much of which hasn’t appeared in print before. This image depicts the azhdarchoid pterosaur Thalassodromeus. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

All in all, The Palaeoartist’s Handbook is an excellent, beautifully produced, well crafted book which contains a wealth of information on the life appearance of extinct animals and how we might imagine them as living things, and it’s phenomenally good on the workings of palaeoart more generally. It should have broader appeal than to the palaeoart fraternity alone, and I think that anyone seriously interested in prehistoric animals or even in the history of art or the way people have imagined the past should obtain it too. For now, Witton (2018) is – mission fulfilled – THE palaeoartist’s handbook indeed.

Mark P. Witton. 2018. The Palaeoartist’s Handbook: Recreating Prehistoric Animals in Art. The Crowood Press, Marlborough (UK), 224 pp, softback, index, refs, ISBN 978-1-78500-461-2. Here on amazon. Here on amazon.co.uk.

For previous TetZoo articles on palaeoart and Wittoniana (the ver 2 and ver 3 ones have been ruined by removal of images), see…

The Great Dinosaur Art Event of 2012, November 2012 (but all images now missing)

All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals - the book and the launch event, December 2012 (but all images now missing)

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014 (but all images now missing)

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

The Natural History Museum at South Kensington, November 2016

Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2016

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 1, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 2, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 3, June 2018

Dinosaurs in the Wild: An Inside View, July 2018

Recollections of Dinosaurs Past and Present, the 1980s Exhibition, February 2019

Refs - -

Paul, G. S. 1987. The science and art of restoring the life appearance of dinosaurs and their relatives - a rigorous how-to guide. In Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present Vol. II. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and London), pp. 4-49.

Up Close and Personal With the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

Like many of us, I have long enjoyed looking at the Crystal Palace dinosaurs and other prehistoric animal models, created in 1854, still on show more than 160 years later, and providing a remarkable showcase of ancient life as it was imagined at the time. But I’ve only ever seen them from afar. How fantastic would it be to examine them up close? Well…

Caption: you’ve seen the Crystal Palace dinosaurs before (or images of them, anyway), but you might not have seen them up-close like this. Neither had I prior to this very special visit. Image: Darren Naish.

Way back in September 2018, I was fortunate enough to attend the Crystal Palace Dinosaur Days event, part of the Heritage Open Days weekend occurring across the UK on the weekend concerned. I gave a talk and also led a tour around the prehistoric animal models (focusing on the reptiles and amphibians alone). Adrian Lister (of mammoth and Megaloceros fame) led a tour too, Mark Witton gave a talk on ‘Palaeoart After Crystal Palace’, and much else happened besides. I also have to mention the 3D-printed models of the dinosaurs made by Perri Wheeler. How I would love for these to be commercially available: I’m sure they’d be a success. So, it was a great event; well done Ellinor Michel and everyone else involved in the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs group (follow them on Twitter at @cpdinosaurs) for putting it together.

Caption: Perri Wheeler’s brilliant models of the three Crystal Palace dinosaurs (from back to front: Megalosaurus, Hylaeosaurus, Iguanodon). As a pathological collector of model dinosaurs, I sure would like to own a set, but I also sure would like for these models (or a set very similar to them) to be commercially available. Image: Darren Naish.

The real thrill, however, was not the talks nor the presence of the amazing and sometimes spectacularly good speakers but the fact that we were awarded special, up-close access to the prehistoric animal models. A dream come true. As you’ll know if you’ve visited Crystal Palace or read about it, the models are located on islands surrounded by a snaking waterway. In other words, they aren’t readily accessible. For the duration of Dinosaurs Days, however, a temporary bridge had been erected and – like Lord Roxton striding across a felled tree to Maple White Land – we made the crossing and stepped into a bygone era.

Caption: the amazing, enormous head of the Mosasaurus. Many of the scales on the body were recently repaired as the entire skin across the body was in a poor state. More on the mosasaur below. Image: Darren Naish.

Why erect a bridge to the islands in the first place? Both so that crucial landscaping and gardening can occur, and so that the models can be examined and evaluated for repair. They’re not in the best of shape, you see, and much work needs doing. Indeed, right now there’s a major push to get funding for a permanent bridge that will allow the continual access that’s required. This project only has a few days of fundraising left and there’s some way to go before the target is reached: go here and chip in if you can. You might have heard that the Mayor of London agreed to partly fund the project… as has legendary musician and song-writer Slash, since it turns out that he’s a big fan! I should add that Slash seems to be quite the fan of science in general, his twitter account revealing a definite tendency to use his powers for good.

Caption: the standing Iguanodon was given renovation and a new paint scheme within recent years. Unfortunately, further repair work is already required. Image: Darren Naish.

The reason I’m writing this article is not just to bring attention to this push for funding, but also to discuss and illustrate various of the remarkable details I got to see thanks to this up-close encounter. Before I start, be sure to read (if you haven’t already) the August 2016 TetZoo ver 3 article on the Crystal Palace models. Thanks to the Dinosaur Days event, I should add that I’ve been able to get hold of the guide that Richard Owen wrote to accompany the exhibition, or the 2013 reprinting (Owen 2013) of this 1864 publication (Owen 1854), anyway. It provides at least some background information on why the animals look the way they do.

Caption: head of the reclining Iguanodon. Only a privileged few have seen the head from its left side. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: again, relatively few people will have seen the reclining Iguanodon from this side. It’s striking how natural, realistic and well-proportioned the model looks in this view: very much like a real animal. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: Hylaeosaurus was thought by Owen and Hawkins to be an iguana-like reptile with a “lofty serrated or jagged crest, extended along the middle of the back”, though many aspects of the reconstruction were noted as being “at present conjectural” (Owen 2013, p. 18). Image: Darren Naish.

I’ll avoid repeating here the same points I made in my 2016 article but I will repeat my primary take-homes. Namely, that it’s disingenuous and naïve to criticise the models as outdated or as inaccurate, laughable follies, as is sometimes done. They have to be seen within the context of what was known at the time, there has to some acknowledgement of the fact that scientific knowledge has improved over time, and there should also be recognition of the fact that the models are more up-to-date than, and superior in technical accuracy and craftmanship to, the vast majority of modern efforts to portray prehistoric life. In the interests of correcting a mistake made in my 2016 article I should also point out that Crystal Palace is not in Sydenham as I stated, but in Penge. With that out of the way…

Caption: the pachydermal, vaguely bear-like Megalosaurus is actually a composite of information compiled from both Jurassic and Cretaceous theropods. The tall shoulder hump was included because Owen erroneously regarded the tall-spined Altispinax (previously Becklespinax) vertebrae as belonging to the shoulder region of Megalosaurus (Naish 2010). Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: a lot of detail was added to the megalosaur’s face, some of it is superficially crocodylian-like. Note the ominous cracks at the tip of the nose and along the side of the lower jaw. Image: Darren Naish.

It was a real thrill to see the remarkably detailed appearance of the three Crystal Palace dinosaurs: Iguanodon, Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus. Each has a very different skin texture, the Megalosaurus being the most unusual in that it doesn’t have the tile-like scales of the other two. Instead, it’s decorated with a crazy-paving-like covering. It’s not clear what Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (the designer and model-maker) was trying to achieve here since this is a rather non-reptilian look. Perhaps the aim was to give the animal a fissured skin texture vaguely like that of elephants.

Caption: view of the interior of the standing Iguanodon, with and without flash. The light at the far end of the image is coming in through the Iguanodon’s mouth. Image: Darren Naish.

Holes on the undersides of the Iguanodon and Hylaeosaurus mean that their insides can be inspected. As you can see from my photos, the models look like weird gabled roofs from the inside, numerous metal struts and poles helping to provide support. The hylaeosaur’s original head was removed since its weight was causing the model’s neck to break, and was replaced with a fibreglass copy. So, peer inside the hylaeosaur from beneath and you see the translucent interior of its face.

Caption: a view of the hylaeosaur’s interior! Image: Darren Naish.

Cracks, fissures and damaged sections are visible everywhere, moss invades and covers parts of the hylaeosaur’s flanks (not good if you want the models to persist) and sections of the megalosaur’s nose look like they could fall off at any moment. Similar damage is present on some of the other models, their skin and scales flaking or cracking or looking to be in imminent danger of breaking or falling off. Some substantial (expensive) repair work has been done by the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, but much more is required.

Caption: looking into the mouth of the Mosasaurus. “The large pointed teeth on the jaws are very conspicuous; but, in addition to these, the gigantic reptile had teeth on a bone of the roof of the mouth (the pterygoid), like some of the modern lizards” (Owen 2013, p. 11). Image: Darren Naish.

In my previous Crystal Palace article, I discussed the fact that the models reveal a great many complex anatomical details, some of them involving details only familiar to specialists. When you see the models up close, even more such details become apparent. I’m not sure I knew that the mosasaur is equipped with accurate palatal teeth, for example. Owen specifically referred to this feature in the guidebook (Owen 2013). The temnospondyls (‘labyrinthodonts’) have big palatal teeth as well, as they should.

Caption: anterior view of one of the temnospondyls. Check out the accurate palatal teeth. To Owen and Hawkins, this animal was Labyrinthodon salamandroides, a sort of composite based on temnospondyl bones and teeth, and inferences made from croc-line archosaur footprints, thought by Owen and those who followed his work to be made by Labyrinthodon. Image: Darren Naish.

Like the dinosaurs (except the megalosaur), the surviving pterosaurs are fantastically scaly (today, we think that pterosaurs were covered in a filamentous coat, except on their wings, the distal parts of their hindlimbs and their snouts and faces). Unfortunately, the pterosaur with folded wings has recently been damaged, its smashed snout and lower jaw meaning that you can see right inside its head. This reveals a complex internal ‘anatomy’: another reminder that the models weren’t all built to the same plan or in the same style, but that very different approaches were used for each.

Caption: the two large Crystal Palace pterosaurs represent the species known to Owen and Hawkins as Pterodactylus cuvieri (though the possibility that more than one species is represented is raised by Owen’s remarks in the accompanying guide). Unfortunately, one of the models is now badly broken. The two smaller pterosaur models are not currently on display and have had a really unfortunate history: they’ve been vandalised, broken and stolen several times. Image: Darren Naish.

Both big pterosaurs stand atop a small rocky ’cliff’. Like all the geological structures in the park, this is an installation specially created as part of the display. It looks, at first sight, to be made of nondescript grey rock. While looking at it, I began wondering about its specific composition, since we know that the other chunks of rocks in the park aren’t just random lumps of local geology, but transplanted sections of the specific geological unit the respective animal’s fossils come from.

Caption: as per usual, the model up-close - this is the Pterodactylus cuvieri posed with open wings - is a remarkable bit of craftmanship. Pterodactylus cuvieri was named for bones that have more recently been included within the genera Ornithocheirus and Anhanguera, and have most recently been awarded the new name Cimoliopterus. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: and here’s a close-up of that detail. I absolutely adore the work here; check out all those individual scales. It seems remarkable now to think that Owen and Hawkins really imagined pterosaurs to look like this, but here’s the evidence. Image: Darren Naish.

What, then, are these pterosaurs really standing on? Mark Witton and I examined some freshly broken fragments of the cliff – the rock is chalk! This really shouldn’t have been a surprise given that the fossils these reconstructions are based on come from the English Chalk (Owen 2013), but it was great to see it confirmed. There’s even a line of dark flint nodules, just as there is in real chalk cliffs. These details are surely known to specialist researchers but were news to me.

Caption: broken sections of the ‘pterosaur cliff’ reveal that we’re looking at chalk… which isn’t a surprise, and is exactly what we would expect, but here’s confirmation. You should be able to see a few of the dark, shiny flint nodules too. Image: Darren Naish.

Look – below – at the photo of the teleosaurs. Notice how the arrangement of scales and scutes is highly detailed, and how the animals have been given a scute arrangement that very much resembles that of living crocodylians. As it happens, the arrangement they’ve been given is dead wrong for teleosaurs but it is absolutely accurate for living crocodylians (where dorsal scute arrangement is – mostly – diagnostic to species level). What I’m saying is that I think that Hawkins looked at living Saltwater crocodiles Crocodylus porosus when designing these amazing models, since their dorsal scute pattern specifically matches this species (and, surprisingly, not gharials).

Caption: the two Teleosaurus of Crystal Palace. While compared by Owen with gharials, it’s interesting that the dorsal scute pattern they were given is very clearly based on living crocodiles. As per usual, look at the remarkable amount of well-rendered detail. Image: Darren Naish.

As usual, there’s stacks more I want to say, but time is up. I had such a great time seeing the models up close and I can’t wait to do it again. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the Crystal Palace prehistoric animals are among the most scientifically and historically important renditions of ancient creatures ever created, and they’re amazing pieces of art, construction and craftmanship to boot. A full, thorough discussion of their ‘anatomy’, backstory, construction and history has, even today, never been published – McCarthy & Gilbert (1994) is the closest thing to it – and much remains to be compiled and discovered.

These models must be preserved for the future. On that note, don’t forget to pledge your support for the bridge project. Crystal Palace and its models will be covered here again at some point in the future, and various relevant projects will be discussed here in 2019 – watch this space!

As should be obvious from these photos, the entire area has become somewhat overgrown recently, and much maintenance is needed. The Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs group are doing what they can, but help is needed. Image: Darren Naish.

For other TetZoo articles on the Crystal Palace prehistoric animals and other relevant issues, see…

The Great Dinosaur Art Event of 2012, November 2012

All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals - the book and the launch event, December 2012

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

Refs - -

McCarthy, S. & Gilbert, M. 1994. Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: The Story of the World’s First Prehistoric Sculptures. Crystal Palace Foundation, London.

Naish, D. 2010. Pneumaticity, the early years: Wealden Supergroup dinosaurs and the hypothesis of saurischian pneumaticity. In Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343, pp. 229-236.

Owen, R. 1854. Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Crystal Palace Library and Euston & Evans, London.

Owen, R. 2013. Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World. Euston Grove Press, London.

The Last Day of Dinosaurs in the Wild

On Sunday 2nd September 2018, the immersive, interactive time-travelling visitor attraction known as Dinosaurs in the Wild closed its doors for the last time… Yes, Dinosaurs in the Wild is now officially off-show,

Caption: preparing to embark on a last ever tour of Late Maastrichtian western North America. Chrononaut Jasmine Arden-Brown introduces us to the world of Chronotex. Image: Darren Naish.

and if you didn’t get to see it before that fateful Sunday… where were you? I was determined to embark on one final tour, and of course I also needed to go to the grand send-off party and say those sad final goodbyes…

As discussed at Tet Zoo several times already (all at ver 3, I hasten to add), I was scientific advisor for this grand project and thus very much feel that the look, behaviour and biology of the Late Cretaceous animals brought to life for the experience was and is ‘mine’, the MAJOR disclaimers being (1) that a whole team of people actually did the work that resulted in the vision coming to fruition, and (2) any ideas that I have about extinct animal biology or appearance or whatever involve the proverbial standing on the shoulders of giants, and the work and discoveries of a great many other people.

Caption: as with any project of this size and scale, there's the long process whereby models and other props come together over time, and then there's the concept art, the explanatory diagrams, and so on. I've kept a record of as much of this stuff as I could. Image: Darren Naish.

With its fully – indeed, extensively – feathered dromaeosaurs, fuzzy-coated, muscular tyrannosaurs, terrestrial stalking azhdarchid pterosaurs (cough cough Witton & Naish 2008 cough cough), sleek, chunky mosasaurs, balloon-faced ankylosaurs and more (Conway et al. 2012), Dinosaurs in the Wild has – I really hope and feel – introduced a substantial chunk of the human public to a very up-to-date view of the Mesozoic world, and has thus gone some way towards undoing the damage of Jurassic World. No to the scaly, shit-brown, roaring monsters of the past, and yes to a more interesting, biologically plausible and often more surprising view of what these animals were like. Incidentally, Colin Trevorrow visited Dinosaurs in the Wild within the last few weeks, spoke to our associate live action director Cameron Wenn, and said really positive things (Colin and I spoke briefly over twitter).

Caption: here are two of the (normally nocturnal) Dinosaurs in the Wild animals seen in full illumination. At left, the metatherian mammal Didelphodon; at right, the small dromaeosaur Acheroraptor (it never stays still for long, hence the motion blur). Image: Darren Naish.

And did Dinosaurs in the Wild have an impact on the public? I don’t know if I’m allowed to release all the figures, but I will say that many thousands of people attended the experience during its 13 or so months of operation at Birmingham, Manchester and London. Our amazing actors and other staff all became worthy ambassadors of ‘new look’ Mesozoic animals and their biology, and the substantial amount of scientific content included in the show surely introduced the public to a great deal of information they haven’t seen or heard before. All results indicate that we certainly received the sort of feedback and accolade we hoped for: we scored really well as goes visitor feedback, indeed sufficiently well that Dinosaurs in the Wild can be regarded as a world class attraction. The palaeontologists and other scientists and experts who visited were all extraordinarily positive, and thanks indeed to those colleagues of mine who voiced their thoughts in public (Dean Lomax, Mark Witton, Albert Chen, Dave Hone, among others).

Caption: our final goodbye party was a solemn, quiet affair. Obviously. Thanks, Mike. Image: Darren Naish.

Our venues were all great – Manchester’s Event City was certainly quite the sight to behold – but were perhaps not as centrally placed as might be ideal, though there are all kinds of factors controlling where and how a given exhibit can be located.

Caption: a very dangerous box. Working in the Mesozoic is not all that easy. Image: Darren Naish.

Even now, and even after me writing that fairly substantial ‘behind the scenes’ article I published at Tet Zoo ver 3 in July 2018 (and here’s assuming that SciAm haven’t removed it due to an issue with image rights, ha ha ha), there’s a huge amount that could be said about the ‘making of’ this project. As some of you already know, the backstory to the world of Dinosaurs in the Wild is already written-up in an extensive document that we took to referring to as The Bible, but despite efforts I’ve had to give up on plans to get it published. I will be talking about much of the ‘behind the scenes’ stuff at TetZooCon this year (BUY TICKETS HERE), however, and will be bringing The Bible along for those interested in seeing it.

Caption: there's so much to see through the windows that, even after multiple visits, I still haven't seen it all. In this sequence (seen while looking across the Dakotaraptor nesting colony), two female dromaeosaurs engage in a squabble. Image: Kerry Mulvihill.

Huge thanks to everyone at the event last night, and to everyone who made Dinosaurs in the Wild the success it was. Special thanks to producers Jill Bryant and Bob Deere, creative director Tim Haines, the team at Freeman Ryan, to live action directors Scott Faris and Cameron Wenn, to all the amazing people at Impossible, Milk VFX and Crawley Creatures, to every single one of our amazing actors, to our support staff, our sponsors and everyone else. And thanks also to Sam, Simon, Heather and the others who accompanied me on the same, final tour I took just yesterday.

Caption: the temporal field generator is always on. Image: Darren Naish.

Is this really the very end of Dinosaurs in the Wild? Will it re-appear elsewhere at some future date? As you might guess, there are certainly plans that such a thing might happen. Right now, I can say no more. News will be reported here, and on relevant social media streams (I'm at @TetZoo, and check @DinosInTheWild too).

Refs - -

Postcranial Palaeoneurology and the Lifestyles of Pterosaurs

Regular readers will know that I – with colleagues – publish fairly regularly on azhdarchoid pterosaurs, the very special pterosaur group that includes the short-faced tapejarids, the sometimes gigantic, long-jawed azhdarchids and a few groups seemingly intermediate between these two. Azhdarchoids are quite obviously the best and most interesting of the pterosaurs. And back in 2013, I and colleagues published a description and analysis of a new species from the Early Cretaceous of the Isle of Wight known only from a three-dimensional pelvis and some associated vertebrae. We called it Vectidraco daisymorrisae, its name honouring Daisy Morris, the young woman who discovered it (Naish et al. 2013).

The Vectidraco daisymorrisae holotype (NHMUK PV R36621) in (A) left lateral, (B) right lateral, (C) dorsal and (D) ventral views, and - at right - shown in anatomical position as per the animal's presumed profile in life. Image: figures from Naish et al. (2013).

Enough is known of Vectidraco for us to make some determination as goes what sort of pterosaur it is (it seems to be a tapejarid or tapejarid-like azhdarchoid), and we can also say interesting things as goes its size and degree of skeletal pneumatisation (Naish et al. 2013). It’s well preserved enough that quite a few other things can be done with it as well. Last year Rachel Frigot used it as a model in the determination of pelvic and hindlimb musculature (Frigot 2017). And, as part of her PhD work on pterosaur pneumaticity and anatomy, my colleague Liz Martin-Silverstone sought to do some neat science with it as well. This work has just been published (Martin-Silverstone et al. 2018), and that’s why we’re here today.

My friend and colleague Dr Liz Martin-Silverstone, at work in the field (at left, Liz is finding fossils in a river in Romania) and in a museum exhibition at right (Liz is standing next to an exhibition panel all about her work. Let's not talk about that weird silhouette at upper right...). Images: Darren Naish.

Much of Liz’s work has involved CT-scanning (you can read about her own adventures here on her blog) and the relationship between pneumatisation, mass and flight. Vectidraco is at the other end of the scale from many of the pterosaurs that Liz has worked on (it was a small pterosaur with a wingspan likely less than 1 m as an adult) and was readily available, so it seemed sensible to incorporate it into her work. We scanned the specimen at its home (the Natural History Museum, London), and compared the results with those obtained from other pterosaurs we had to hand: namely, the ornithocheirids* Anhanguera and Coloborhynchus, scanned variously at Stony Brook University Hospital (thanks to Pat O’Connor for that data) and at the µ-VIS (pronounced ‘mu-vis’) X-Ray Imaging Centre at the University of Southampton (Martin-Silverstone et al. 2018). And we got pretty good results.

* Ornithocheirids: the mostly marine, long-jawed, long-winged pterodactyloid pterosaur group named for Ornithocheirus from the 'middle' Cretaceous of the UK. The group names Anhangueria and Anhangueridae refer to the same group... views differ on which taxonomic system we should adopt.

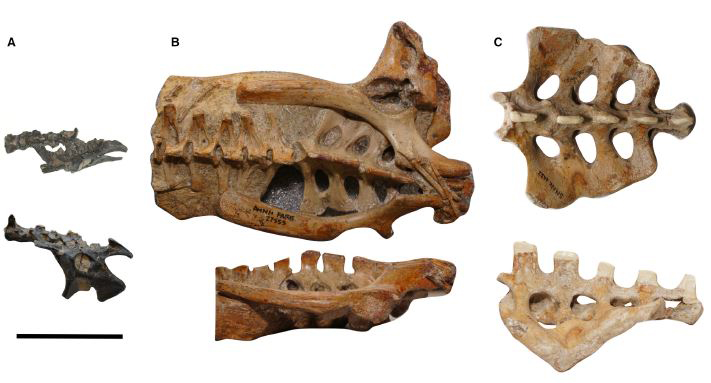

Pelvic regions of the three pterosaurs included in our study, to scale: (A) Vectidraco daisymorrisae holotype NHMUK PV R36621, (B) Anhanguera specimen AMNH FARB 22555, (C) Coloborhynchus robustus specimen SMNK PAL 1133. Scale bar = 50 mm. Image: Martin-Silverstone et al. (2018).

The first interesting thing to note is that the work corrects, updates and augments various anatomical details I reported in the initial description of Vectidraco (Naish et al. 2013). Bony openings that I interpreted as pneumatic foramina turn out to be foramina for spinal nerves (properly termed intervertebral foramina), and convex transverse ridges present on the sides and undersides of some of the vertebrae are misidentified intervertebral junctions. Cool – it’s good to learn more. The identification of intervertebral foramina is not a big deal at all given that these structures are ubiquitous in tetrapods but it's worth bringing attention to them given that they’re virtually unmentioned elsewhere in the pterosaur literature.

The Vectidraco holotype is one of those wonderful specimens that preserves a great many neat little anatomical details - look at these various pneumatic cavities on the T-shaped post-acetabular process on the posterior part of the ilium. Waitaminute.... aren't all the specimens like this? Image: Darren Naish.

And if you’re wondering why I and my colleagues didn’t CT-scan the specimen the first time around and get this stuff correct on our first, 2013 attempt, it’s because CT-scanning requires money and virtually everything I do has been, and is, unfunded.

Anyway… what else could we do with the CT-scan data? Well…

During the late 1980s and 90s, Emily Giffin (later Emily Buchholtz) published several papers in which she used data from the size of the neural canal in the vertebrae of fossil tetrapods to make inferences about nerve size, the size then serving as a proxy for degree of innervation, this then serving as a guide to things like limb function and posture (Giffin 1989, 1990, 1992, 1995a, b). Her studies looked variously at non-bird theropods, extinct crocodylians and fossil pinnipeds, and she reported encouraging results. Non-bird theropods with large hands, to take one example, possessed neural canals in the corresponding part of the spine that were proportionally large, and hence suggestive of the well-developed nervous anatomy we would expect for animals that regularly used their hands in grabbing, piercing and tearing (Giffin 1995a). Her work has inspired other researchers to use the same (or similar) techniques on plesiosaurs and fossil raptors (again, here’s your helpful reminder that I will only ever use this term in the correct fashion. It applies to hawks, eagles and falcons and has done since the 1800s at least).

In a series of really interesting papers, Emily Giffin linked neural canal size with form and function in diverse tetrapods. This graph (from Giffin 1995b) shows how birds flying and flightless differ as goes the position of the largest parts of their spinal cords. The ostrich (Struthio) lacks a large spinal cord section in the anterior (brachial) part of its spinal column. Image: Giffin (1995b).

Several caveats make this technique far from fool-proof (Giffin 1995a). With these things in mind, we wondered if data from pterosaurs might be informative as goes ideas on their ecology and lifestyle. What we found is that Vectidraco has an unusually large neural canal in its sacral region compared to Anhanguera, indicating that it therefore had a proportionally large spinal cord (and lumbosacral plexus) in its lumbosacral region. Anhanguera and Coloborhynchus both had enlarged neural canals in the area corresponding to the brachial plexus, larger than the neural canals in their sacral regions. Vectidraco’s shoulder region is entirely unknown at the moment so we couldn't make any comparison here.

Neural canal cross-sectional area in our three pterosaur taxa: when normalised for centrum size, Vectidraco has a proportionally large neural canal. This composite image incorporates figures from Martin-Silverstone et al. (2018) but was produced by the Palaeontological Association. Image: Martin-Silverstone et al. (2018).

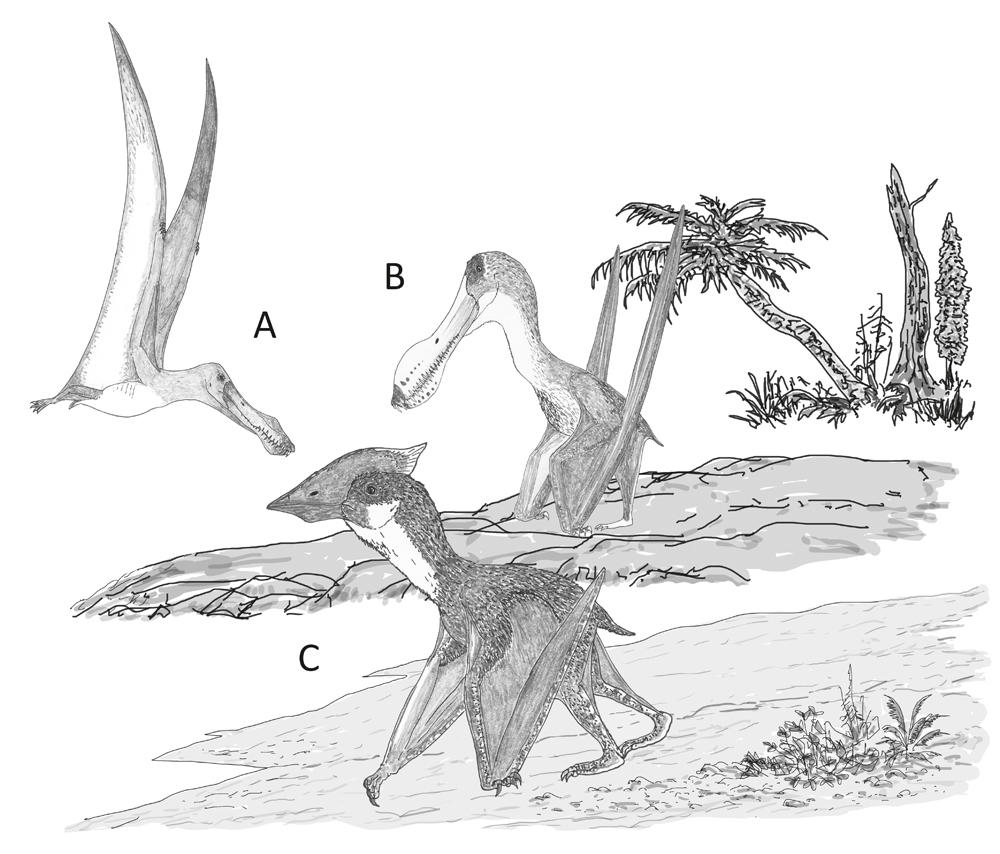

Taken together this suggests the following: evidence for a large brachial enlargement in ornithocheirids is consistent with the idea (based on their long, high-aspect wings and small hindlimbs) that they were highly aerial animals, while the large sacral neural canal in Vectidraco indicates that it was more proficient at terrestrial locomotion than Anhanguera. There are already indications from pelvic morphology, hindlimb size and so on that azhdarchoids and ornithocheirids were doing very different things in terms of ecology and behaviour (Witton & Naish 2008, 2015, Witton 2013, Naish & Witton 2017), so this matches what we might predict.

Vectidraco could almost certainly fly well, as shown at left. But - like many, most or all azhdarchoids - it was likely a proficient and regular terrestrial walker as well, as shown at right. Image: Mark Witton (left), Darren Naish (right).

So far so good. But the complication comes from the second ornithocheirid we looked at: Coloborhynchus. Oh, here I’ll avoid the whole mess concerning the taxonomy of Anhanguera and Coloborhynchus. All I’ll do for now is say that “it’s complicated” and promise that I’ll come back to it in the near future. Anyway… the Coloborhynchus specimen we analysed is not like our Anhanguera specimen as goes the proportional size of the neural canal in its lumbosacral region -- it lacks a distinct lumbosacral enlargement but is superficially Vectidraco-like in having a larger neural canal in the relevant region (Martin-Silverstone et al. 2018). This is an unexpected result. Does it mean that some ornithocheirids were far more terrestrially capable than others, this perhaps reflecting niche differentiation or some other form of variation? Or does it mean that some ornithocheirids were far more aerially specialised than others and that the default condition was to have a larger sacral neural canal? Or does it mean that there’s something else we haven’t accounted for? (example: maybe some of these pterosaurs had enlarged neural canals due to pneumatisation in the neural canal? Yes, air sacs dorsal to the spinal cord. This is a thing). I don’t think it means that Coloborhynchus-type pterosaurs were as terrestrially proficient as Vectidraco, nor that our ideas on said terrestrial proficiency in azhdarchoids like Vectidraco are bogus, given the fact that Vectidraco appears to have a lumbosacral enlargement while the ornithocheirids do not, and that azhdarchoids like Vectidraco possess weird features indicative of terrestrial specialisation (like the giant, T-shaped postacetabular process on the ilium) lacking in ornithocheirids. But it’s clear that more data and more work is needed, as usual with these sorts of things.

Behaviour speculatively inferred for the pterosaurs incorporated in our study. (A) A dedicated aerial lifestyle involving little terrestrial behaviour, as per Anhanguera; (B) reasonable terrestrial abilities in an animal otherwise very similar to its close, highly aerial relatives, as per Coloborhynchus; (C) proficient and regular terrestrial behaviour in an animal that routinely feeds and forages on the ground, as per Vectidraco. Image: Darren Naish.

It’s also important to remember that this data – this work as a whole – is complimentary to other studies. CT scan data on neural canal size provides nothing like a ‘Rosetta Stone’ on behaviour or lifestyle, and the more we learn about anatomy and form-function correlation, the less likely it seems that such things exist. We already have lots of reasons for thinking that azhdarchoids were better adapted for terrestriality and life in cluttered, inland settings than were many other pterosaurs, and likewise there are excellent reasons for thinking that ornithocheirids were aerial specialists and something like frigatebirds as goes ecology and lifestyle (though seemingly capable of swimming and perhaps diving, in contrast to the more piratical frigatebirds). So, this work is part of the dataset, part of the puzzle. And this is effectively an opening foray in this most intriguing area.

That’s where we’ll end for now. More on pterosaurs here soon!

For previous Tet Zoo articles on pterosaurs, see...

Shemhazai and other flightless pterosaurs, September 2008

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Giant pterosaurs invade London, Summer 2010, July 2010

Pterosaurs, err, indoors (the Summer 2010 exhibition), July 2010

The Cretaceous birds and pterosaurs of Cornet: part II, the pterosaurs, September 2010

What does it feel like to get bitten by a ground hornbill, I hear you ask?, June 2011

A new azhdarchid pterosaur: the view from Europe becomes ever more interesting, Jan 2013

Daisy’s Isle of Wight Dragon and why China has what Europe does not, March 2013

In Rio for the 2013 International Symposium on Pterosaurs, May 2013

Quetzalcoatlus: the evil, pin-headed, toothy nightmare monster that wants to eat your soul, August 2013

Were azhdarchid pterosaurs really terrestrial stalkers? The evidence says yes, yes they (probably) were, December 2013

Some Azhdarchid Pterosaurs Were Robust-Necked Top-Tier Predators, February 2017

Refs - -

Frigot, R. 2017. Pelvic musculature of Vectidraco daisymorrisae and consequences for pterosaur locomotion. In Hone, D. W. E., Witton, M. P. & Martill, D. M. (eds) New Perspectives on Pterosaur Palaeobiology. Geological Society, London, Special Publications Special Publications 455, 45-55.

Giffin, E. B. 1989. Gross spinal anatomy and limb function in living and fossil reptiles and birds. American Zoologist 29, 181A.

Giffin, E. B. 1990. Gross spinal anatomy and limb use in living and fossil reptiles. Paleobiology 16, 448-458.

Giffin, E. B. 1992. Functional implications of neural canal anatomy in recent and fossil marine carnivores. Journal of Morphology 214, 357-374.

Giffin, E. B. 1995a. Functional interpretation of spinal anatomy in living and fossil amniotes. In Thomason, J. J. (ed) Functional Morphology in Vertebrate Paleontology. Cambridge University Press, pp. 235-248.

Giffin, E. B. 1995b. Postcranial paleoneurology of the Diapsida. Journal of Zoology 235, 389-410.

Martin-Silverstone, E., Sykes, D. & Naish, D. 2018. Does postcranial palaeoneurology provide insight into pterosaur behaviour and lifestyle? New data from the azhdarchoid Vectidraco and the ornithocheirids Coloborhynchus and Anhanguera. Palaeontology 2018, 1-14. doi: 10.1111/pala/12390

Naish, D., Simpson, M. I. & Dyke, G. J. 2013. A new small-bodied azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of England and its implications for pterosaur anatomy, diversity and phylogeny. PLoS ONE 8 (3): e58451.

Witton, M. P. 2013. Pterosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton & London.