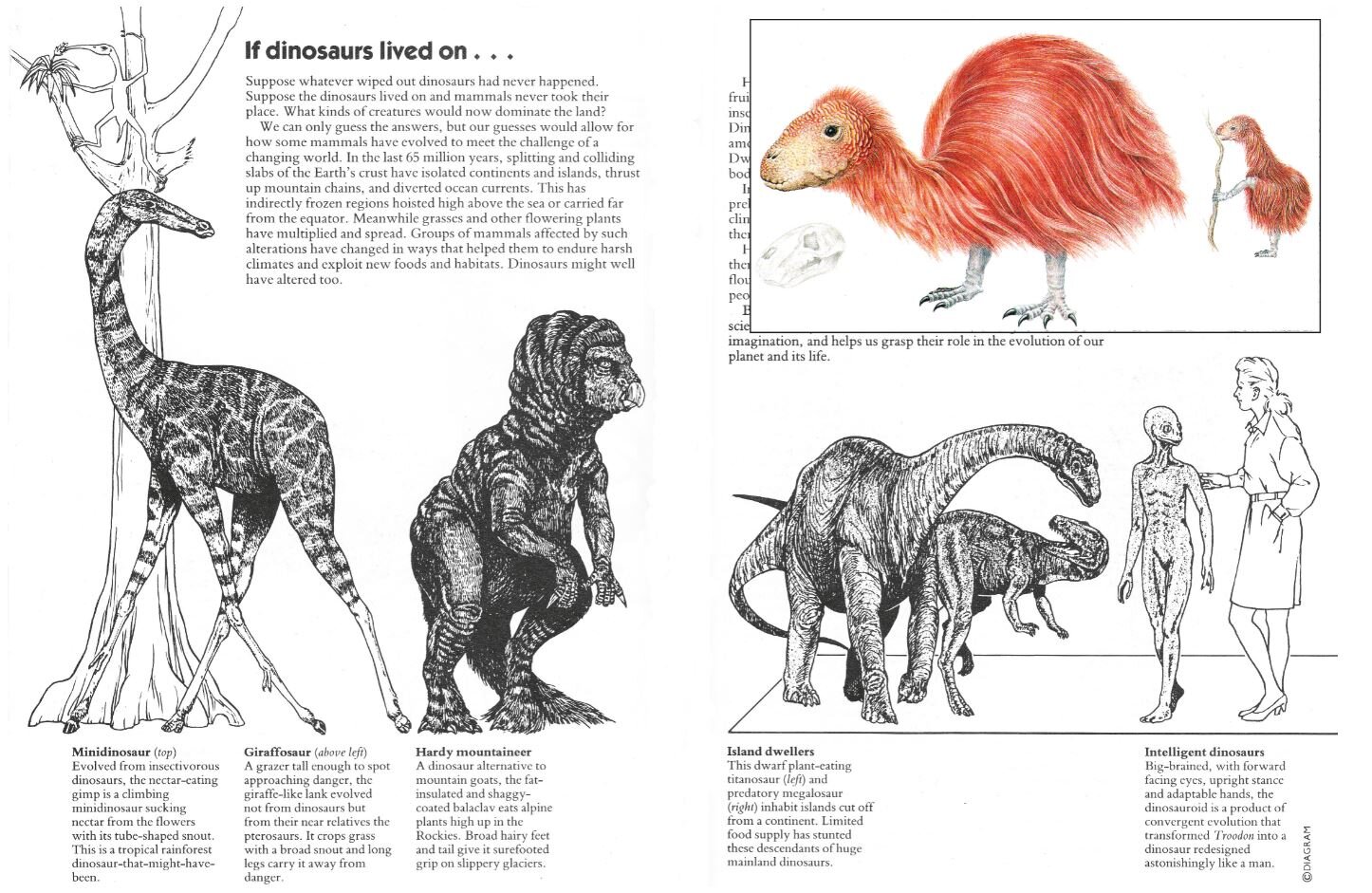

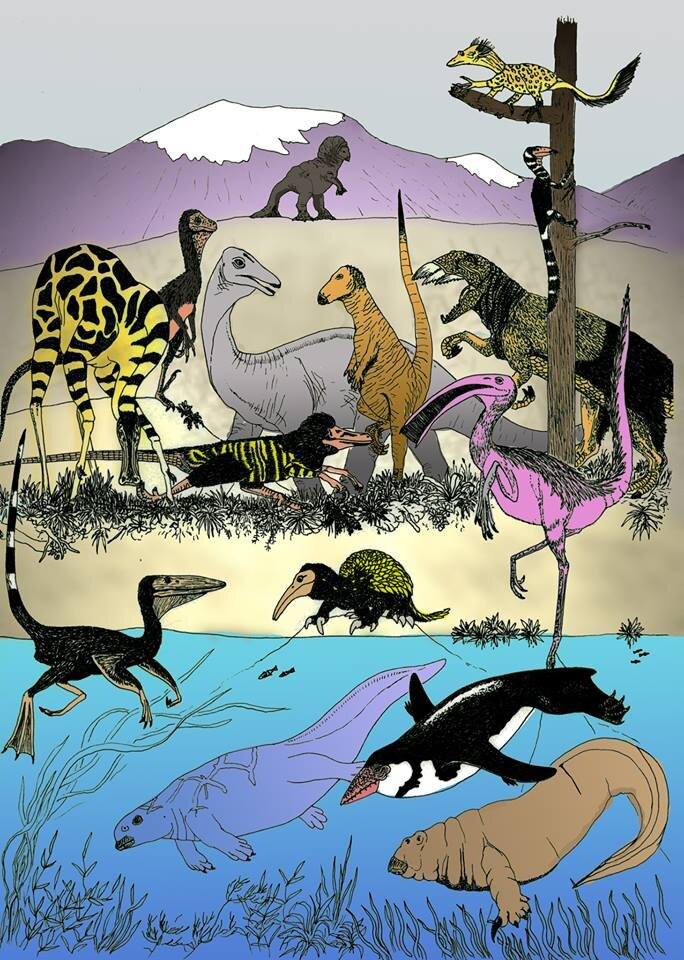

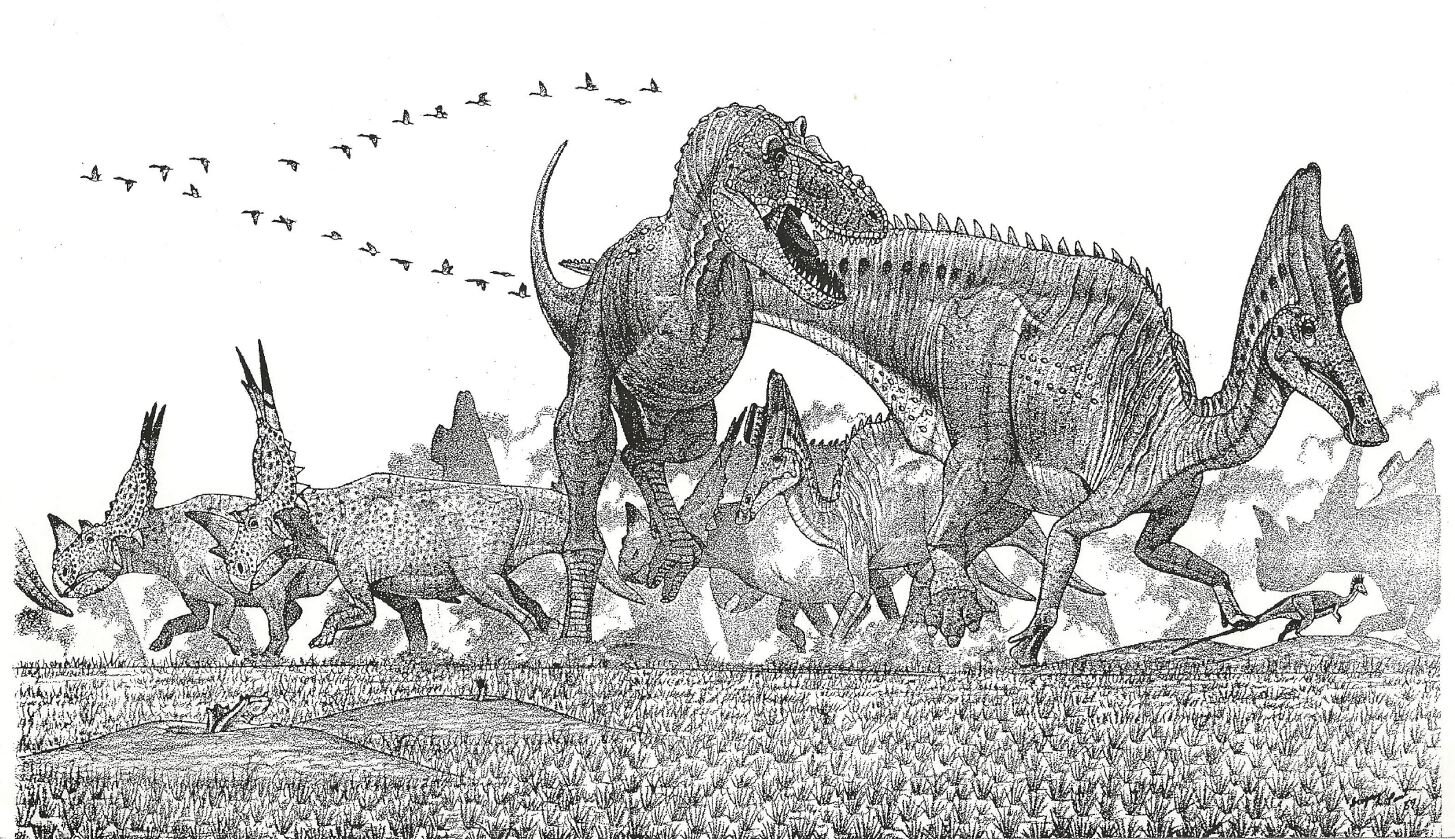

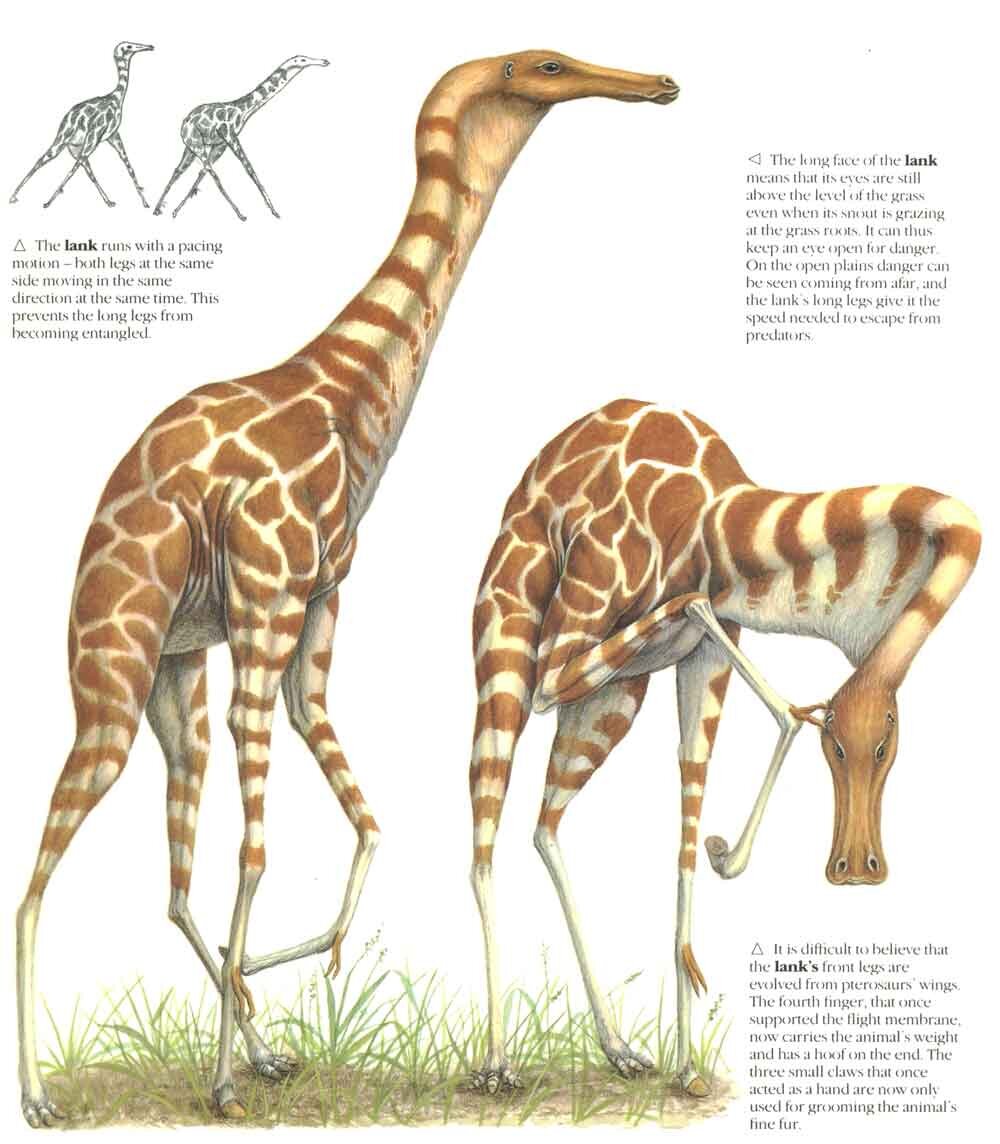

Within recent decades, four specific areas of palaeontological discovery and reinterpretation have succeeding in capturing mainstream attention: the feathering of dinosaurs, the evolution of hominins, the early history of whales, and the early evolution, anatomy and biology of the earliest tetrapods. And it’s the last of those subjects we’re focusing on here. It’s a subject which has seen regular airing in top-tier journals, science magazines and TV documentaries, and one which has undergone a major and exciting revolution since the 1980s.

Caption: at left, Professor Jenny Clack, in the field at Burnmouth in the Scottish Borders. At right: in 2017, Jenny and her husband Rob got to fly in a Spitfire. Images: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

One person above all others has been responsible for leading research in this field and has made numerous ground-breaking discoveries herself, both in the field and laboratory. I am of course referring to Professor Jenny Clack of the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge, an excellent and highly respected scientist whose technical papers are authoritative, ground-breaking and of the highest standard. Her publication list is formidable. Alas, I regret to write that I’m here for sad reasons, since Jenny died on the morning of 26th March 2020 following a five-year struggle with cancer. While – for my shame – I haven’t written about early tetrapod evolution here at TetZoo before, nor about Jenny’s research specifically, both are areas I’ve avidly followed, and I want to share some brief thoughts here.

Caption: a selection of Clack publications in the TetZoo library. Image: Darren Naish.

Prior to Jenny’s work, the consensus view on the oldest tetrapods – in particular Ichthyostega from the Devonian of Greenland – is that these were ‘terrestrialised’, vaguely salamander-like quadrupeds, well able to walk on land by planting all four feet on the substrate. This view, entrenched in textbooks and the popular literature, mostly owed itself to the work of Swedish palaeontologist Erik Jarvik whose work on Ichthyostega, while initiated in the 1950s, took some decades to appear, finally being published in 1996. Jarvik’s work has its own long and curious backstory (Ries 2007) – which I can’t cover here – and it certainly wasn’t missed by some of us that the conclusions of his supposedly definitive monograph were being called into doubt just weeks after its appearance (Norman 1996).

Caption: Jenny Clack (and Professor Robert Insall) at the Ballagan Formation type locality, near Glasgow. Image: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

Tantalising remains of an Ichthyostega contemporary – the smaller Acanthostega – were discovered in East Greenland on a Cambridge University expedition of 1970 (and were languishing, unrecognised, in the drawers of the university’s earth sciences department prior to Jenny’s interest). These indicated that, with luck, more early tetrapod finds might be discovered in the same region. After making special arrangements with Danish scientists – and with Jarvik, who the Danes wanted to remain on good terms with – Jenny visited Greenland in 1987; she was accompanied by colleagues from Copenhagen, her husband Rob and her then PhD student Per Ahlberg (Clack 1988). They were remarkably successful, retrieving multiple good specimens, and continued to be so on later trips to the same region.

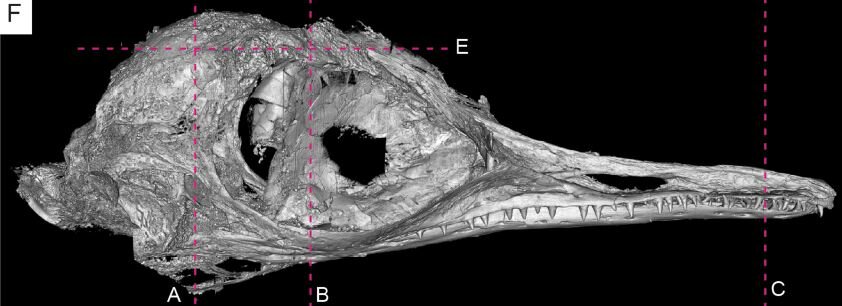

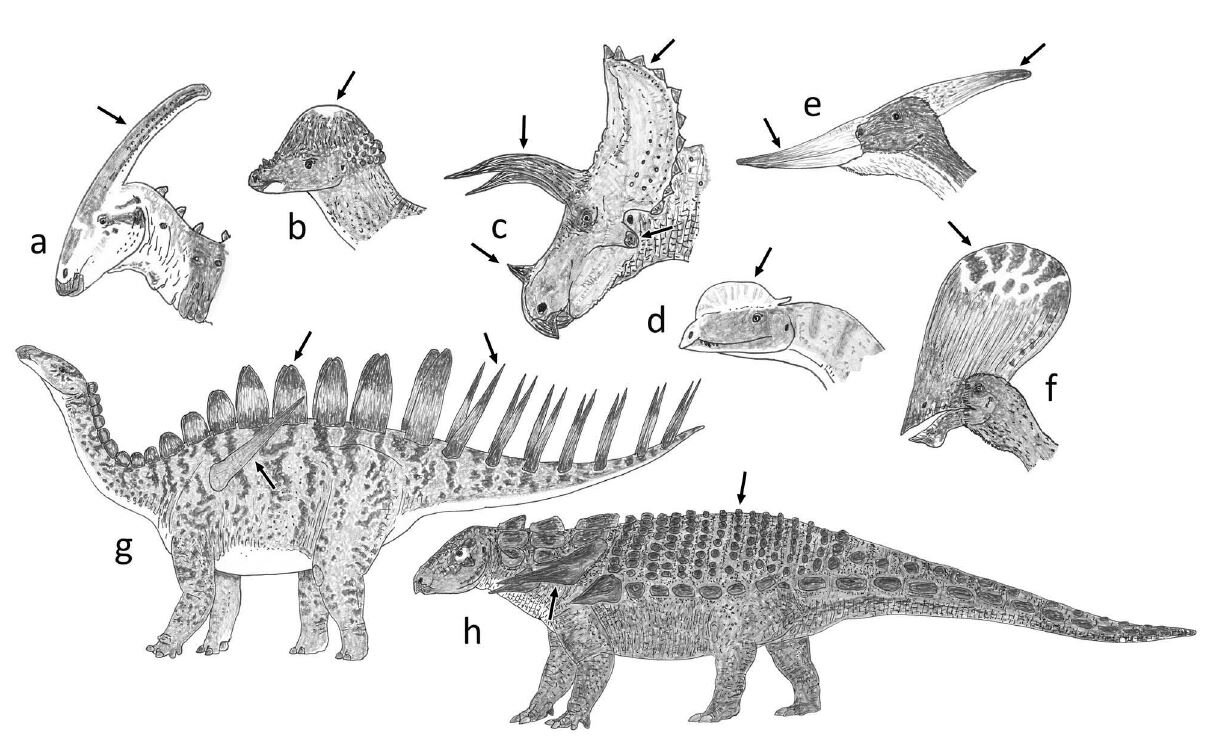

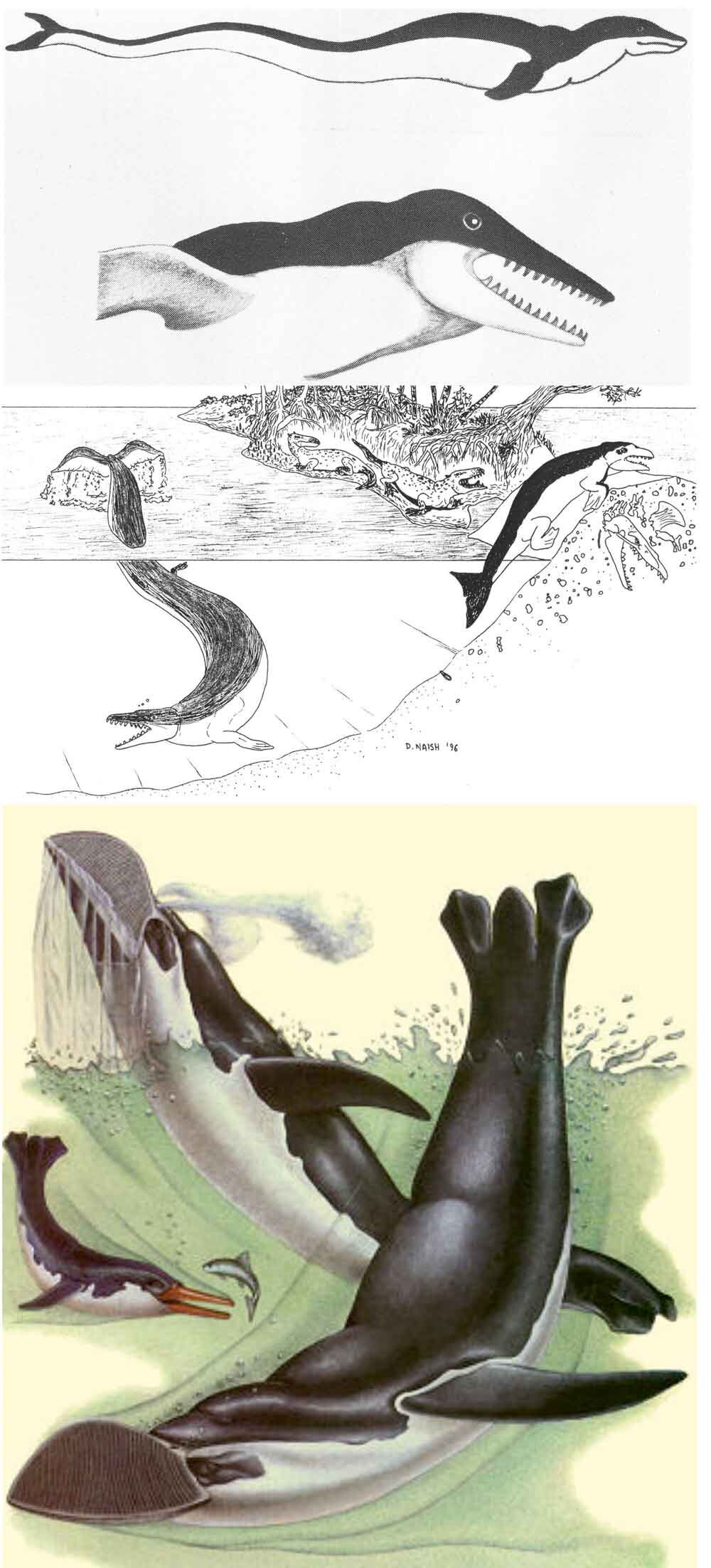

Caption: in more recent years, it’s become obvious that Ichthyostega - the classic ‘early tetrapod’ - was not just a formidable, toothy predator, but an unusual, specialised animal with paddle-like hindlimbs, a proportionally short tail and a regionalised vertebral column. Image: Ahlberg et al. (2005).

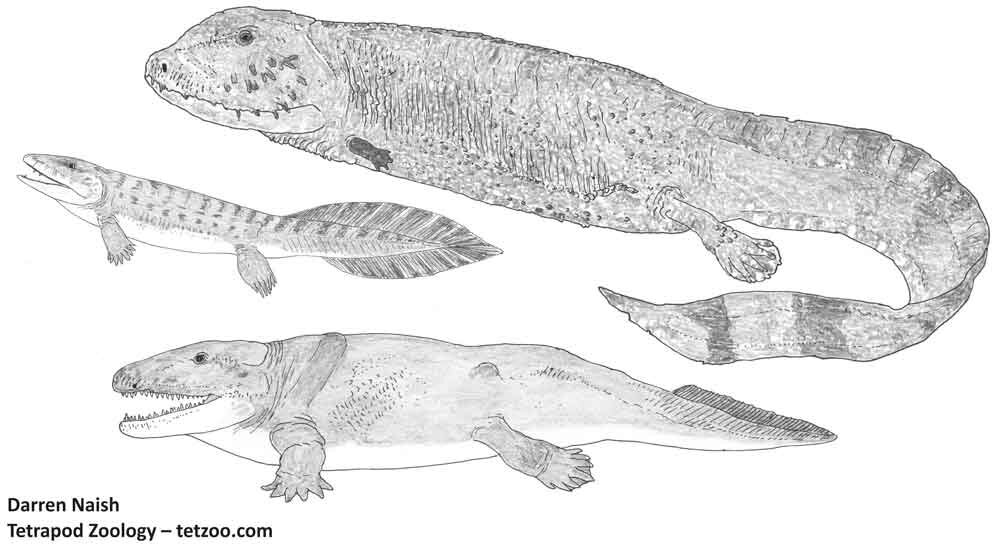

Was Jarvik right about these animals? Not really, no. The discovery of numerous aquatic specialisations in Ichthyostega and the smaller Acanthostega – published by Mike Coates and Jenny during the early 1990s (Coates & Clack 1990, 1991) – was a huge surprise. Tetrapods didn’t start their history as land-walking animals with pentadactyl hands and feet, as Jarvik (and just about everyone else) had thought, but were aquatic and polydactyl, with 8 fingers and 7 toes (or thereabouts)! Later work showed that Ichthyostega had an unusual ear perhaps specialised for aquatic hearing (Clack et al. 2003) and a remarkable regionalised vertebral column and other peculiarities (Ahlberg et al. 2005) suggesting that, when on land, it might have moved in mudskipper-like fashion (Ahlberg et al. 2005, Pierce et al. 2012, 2013).

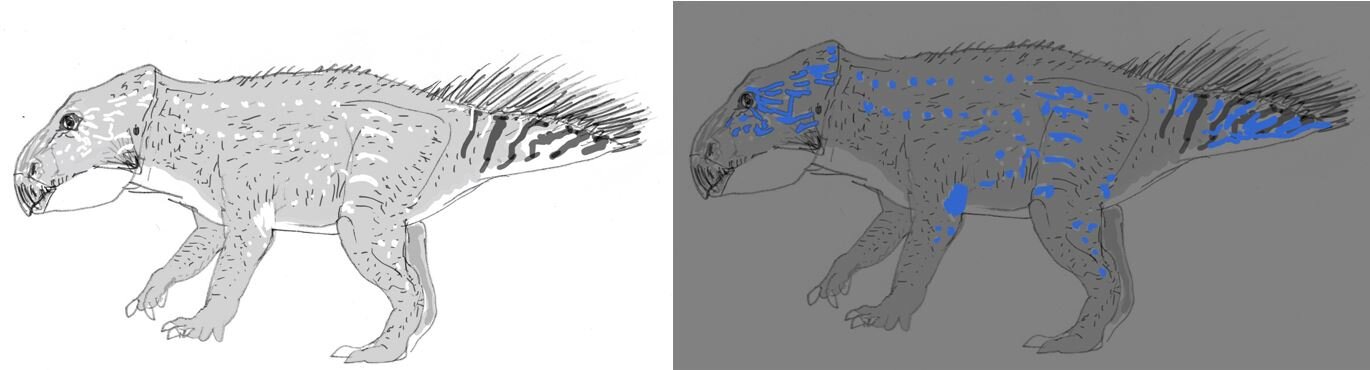

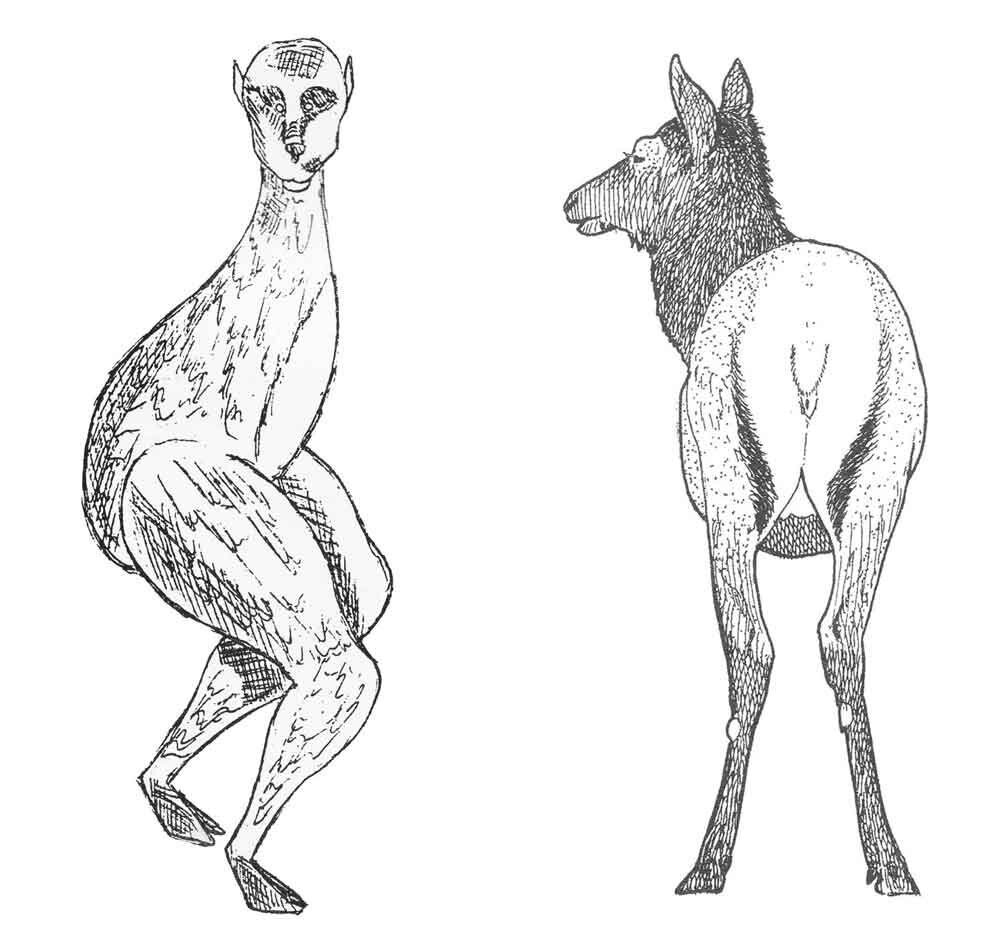

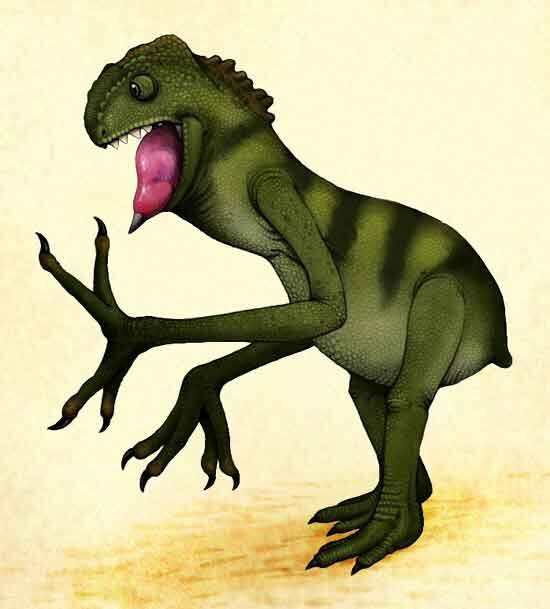

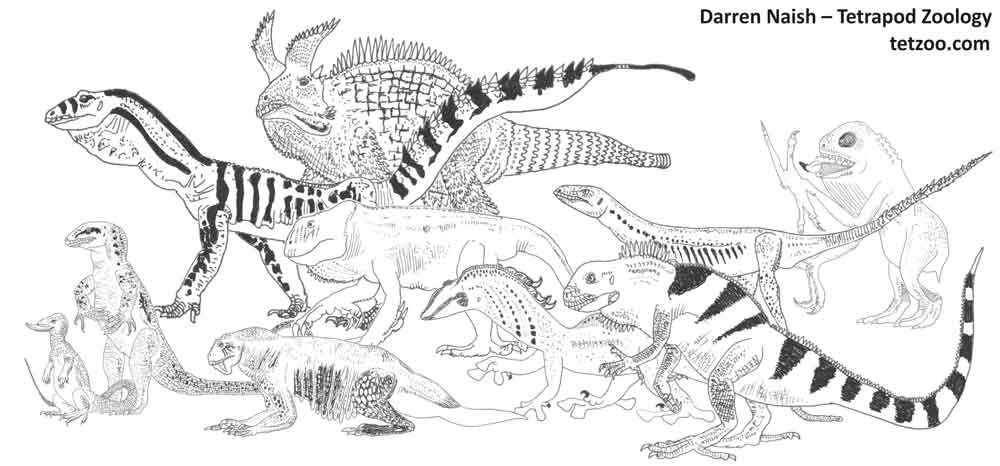

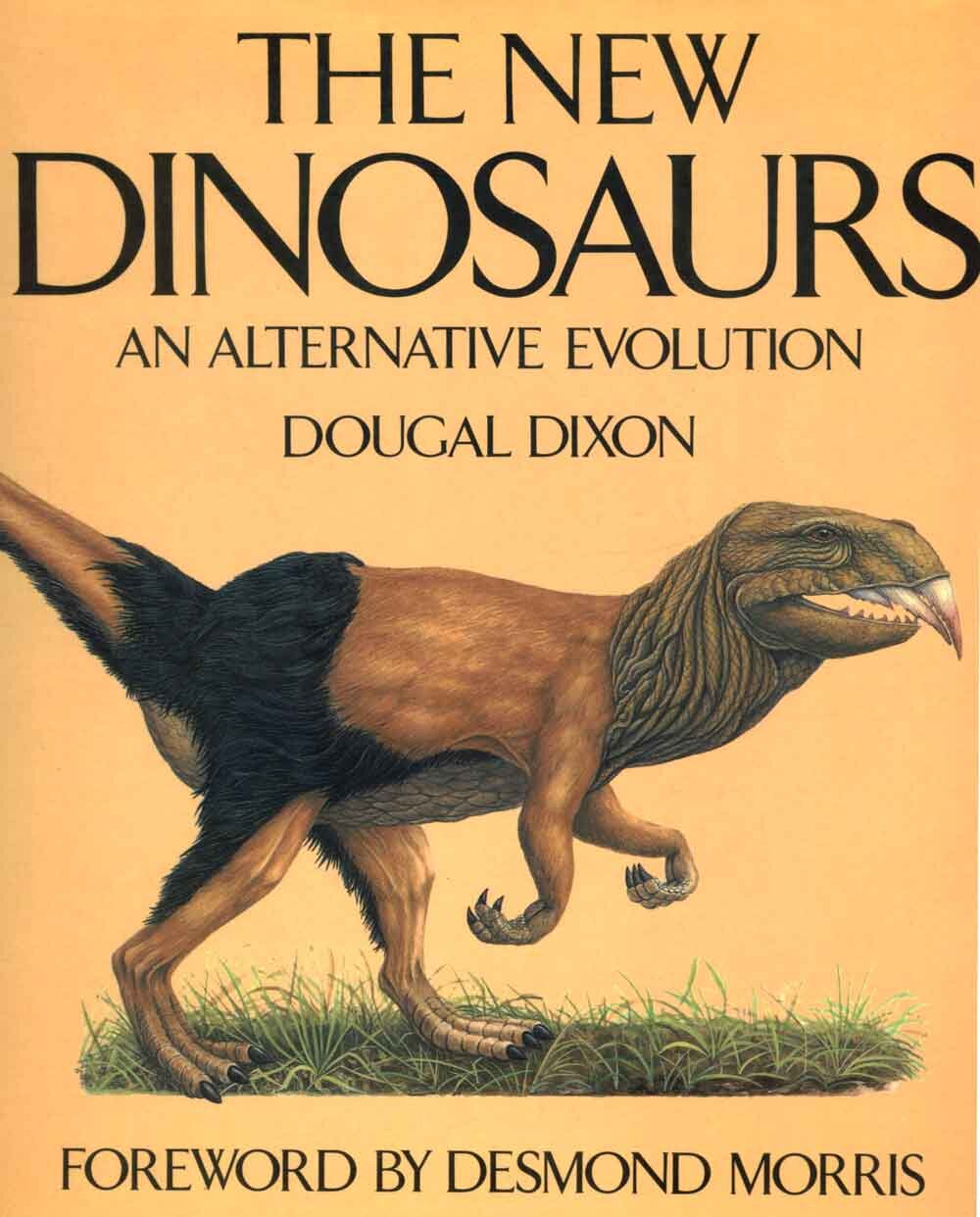

Caption: life reconstructions of three early tetrapods worked on by Clack: the big Crassigyrinus, the small, aquatic Acanthostega, and the big (c 1 m long) Ichthyostega. These images are among tens of archaic tetrapods reconstructed for my in-prep textbook. I’ve learnt recently that the Crassigyrinus will soon need revising. Image: Darren Naish.

Jenny’s work wasn’t limited to this fundamental reinterpretation of the earliest tetrapods, but also involved taxa from throughout the Devonian and Carboniferous. She revised knowledge of the remarkable aquatic Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus (Clack 1998a), described the new species Eucritta melanolimnetes (Clack 1998b), Pederpes finneyae (Clack 2002a, Clack & Finney 2005), Kyrinion martilli (Clack 2003) and others, reported entire new faunal assemblages (Clack et al. 2016) and published key interpretations of such groups as embolomeres (Clack 1987, Clack & Holmes 1988), chroniosuchians (Clack & Klembara 2009, Klembara et al. 2010) and microsaurs (Clack 2011). This extensive, substantial experience made her the right person to publish an authoritative and comprehensive book on Devonian and Carboniferous tetrapods: Gaining Ground: The Origin and Evolution of Tetrapods appeared in 2002 (Clack 2002). It went to second edition in 2012. It’s the best guide to early tetrapod evolution and fills a much-needed gap in the semi-technical literature, and I strongly recommend it to those interested in the subject.

Caption: covers of the first and second editions of Clack’s Gaining Ground. The cover images are, respectively, by Jenny Clack and Julia Molnar. The Clack image shows two individuals engaging in courtship: the green hump at the back left is the body of a second animal.

I never had the privilege of working with Jenny or of accompanying her in the field, but I did have reason to speak to her on several occasions, and to correspond with her. She was friendly and generous with her time and went to trouble to provide me with information and illustrations on an occasion when email wasn’t doing its job. It’s also obvious that she had a sense of humour. Of those new species listed above, Eucritta melanolimnetes translates roughly as ‘creature from the black lagoon’. Some – probably all – of the Ichthyostega and Acanthostega specimens she discovered in Greenland had nicknames: I’m pretty sure I recall seeing that one of them was called Grace Jones. Those who knew her so much better confirm that she was excellent fun, a great leader in the field, and a brilliant mentor.

Caption: several of the archaic Devonian tetrapods study by Clack and her colleagues are excellent, 3D and with very detailed preservation. This image shows an Acanthostega gunnari cast at Musee De L'Histoire Naturelle, Brussels. Image: Ghedoghedo. CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Jenny began her scientific career during the early 1970s and received her PhD at the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne in 1984 under Alec Panchen. Panchen initially offered her a PhD following anatomical discoveries she made while preparing the notoriously difficult holotype specimen of the Carboniferous embolomere Pholiderpeton, initially described by Thomas Huxley in 1869. She joined the University of Cambridge in 1981 and for more than ten years was Assistant Curator at the University’s Museum of Zoology, later being promoted to Senior Assistant Curator and then Curator. She supervised a number of people who went on to become well known in vertebrate palaeontology and evolutionary biology, among them Mike Lee (whose PhD was specifically on pareiasaurs), sauropod expert Paul Upchurch, and actinopterygian fish worker Matt Friedman.

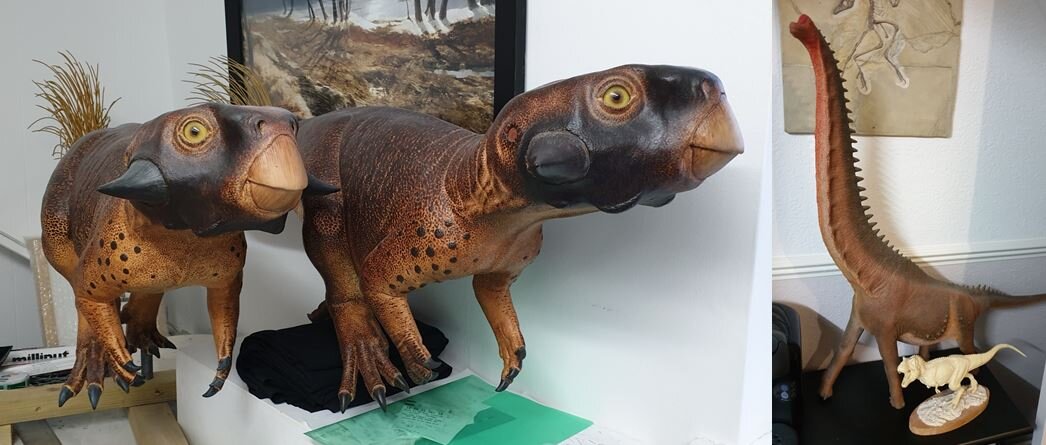

Caption: life-sized models of Ichthyostega and Acanthostega have been made a few times. Here’s the Acanthostega on show at the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge. I’ve photographed this model several times but none of my photos are that good - I stole this image from Christian Kammerer (source).

Jenny retired in 2015. As you might expect give her scientific achievements, she was highly decorated, holding several palaeontological medals, additional, honorary doctorates and other awards too. Such was mainstream interest in her work and ideas that a 2012 episode of the BBC series Beautiful Minds was devoted to her (it’s viewable here on youtube); among other interesting things, it reveals that she was inspired during her childhood years by newts and freshwater fishes, and that it was learning about Mary Anning which encouraged her to pursue palaeontology. She liked motorbikes and cats, and some of the documentaries that focus on her work show her riding around on her motorbike.

Caption: the Tournaisian rocks of Burnmouth, north of Berwick-upon-Tweed, have, within recent decades, proved an important new locality for tetrapods. As a consequence, Jenny and colleagues set up the TW:eed Project, the acronym standing for Tetrapod World: Early Evolution and Diversity. Jenny (in the green top) stands close to the middle. Image: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

My text here only touches on a few aspects of her achievements, life and technical contributions, and I know that much else could be said. I’m very saddened to hear of her passing, very much regarded her as an excellent scientist who published exciting research, and I’ll miss her as a regular attendee of palaeontological meetings. My sincere condolences to her husband Rob, and to those others who knew and loved her.

Some of the text here is adapted from my in-prep giant textbook on the vertebrate fossil record.

The University of Cambridge website on Professor Clack is here

An excellent website on Professor Clack’s research and expeditions is here

Refs - -

Ahlberg, P. E., Clack, J. A. & Blom, H. 2005. The axial skeleton of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 437, 137-140.

Clack, J. A. 1987. Two new specimens of Anthracosaurus (Amphibia: Anthracosauria) from the Northumberland coal measure. Palaeontology 30, 15-26.

Clack, J. A. 1988. Pioneers of the land in East Greenland. Geology Today 4 (6), 192-194.

Clack, J. A. 1998a. The Scottish Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus scoticus (Lydekker) – cranial anatomy and relationships. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences 88, 127-142.

Clack, J. A. 1998b. A new Early Carboniferous tetrapod with a mélange of crown-group characters. Nature 394, 66-69.

Clack, J. A. 2002a. An early tetrapod from 'Romer's Gap'. Nature 418, 72-76.

Clack, J. A. 2003. A new baphetid (stem tetrapod) from the Upper Carbinoferous of Tyne and Wear, U.K., and the evolution of the tetrapod occiput. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40, 483-498.

Clack, J. A. 2011. A new microsaur from the Early Carboniferous (Viséan) of East Kirkton, Scotland, showing soft tissue evidence. Special Papers in Palaeontology 86, 45-55.

Clack, J. A., Ahlberg, P. E., Finney, S. M., Dominguez Alonso, P., Robinson, J. & Ketcham, R. A. 2003. A uniquely specialized ear in a very early tetrapod. Nature 425, 65-69.

Clack, J. A., Bennett, C. E., Carpenter, D. K., Davies, S. J., Fraser, N. C., Kearsey, T. I., Marshall, J. E. A., Millward, D., Otoo, B. K. A., Reeves, E. J., Ross, A. J., Ruta, M., Smithson, K. Z., Smithson, T. R. & Walsh, S. A. 2016. Phylogenetic and environmental context of a Tournaisian tetrapod fauna. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1: 0002.

Clack, J. A. & Finney, S. M. 2005. Pederpes finneyae, an articulated tetrapod from the Tournaisian of western Scotland. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 2, 311-346.

Clack, J. A. & Holmes, R. 1988. The braincase of the anthracosaur Archeria crassidisca with comments on the interrelationships of primitive tetrapods. Palaeontology 31, 85-107.

Clack, J. A. & Klembara, J. 2009. An articulated specimen of Chroniosaurus dongusensis and the morphology and relationships of the chroniosuchids. Special Papers in Palaeontology 81, 15-42.

Coates, M. I. & Clack, J. A. 1990. Polydactyly in the earliest known tetrapod limbs. Nature 347, 66-69.

Coates, M. I. & Clack, J. A. 1991. Fish-like gills and breathing in the earliest known tetrapod. Nature 352, 234-236.

Klembara, J., Clack, J. A. & Čerňanský, A. 2010. The anatomy of palate of Chroniosuchus dongusensis (Chroniosuchia, Chroniosuchidae) from the Upper Permian of Russia. Palaeontology 53, 1147-1153.

Norman, D. 1996. [Review of] The Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Palaeontological Newsletter 31, 13-15.

Pierce, S. E., Ahlberg, P. E., Hutchinson, J. R., Molnar, J. L., Sanchez, S., Tafforeau, P. & Clack, J. A. 2013. Vertebral architecture in the earliest stem tetrapods. Nature 494, 226-229.

Pierce, S. E., Clack, J. A. & Hutchinson, J. R. 2012. Three-dimensional limb joint mobility in the early tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 486, 523-526.

Ries, C. J. 2007. Inventing ‘the four-legged fish’. The palaeontology, politics and popular interest of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega, 1931-1955. Ideas in History 2, 37-78.

![It’s well known in the theropod research community that the full description of this amazing fossil - the holotype of the Spanish ornithomimosaur Pelecanimimus - was done back in the 1990s [UPDATE: nope, 2004], but hasn’t seen print for a bunch of r…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/510be2c1e4b0b9ef3923f158/1585002681161-29JO3RG3SRL02I363HHH/Wealden-theropod-questions-Mar-2020-Pelecanimimus-holotype-skull-1274px-250kb-Mar-2020-Darren-Naish-Tetrapod-Zoology.JPG)