Regular readers of this blog should know that 2016 saw the publication of the Natural History Museum book Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, co-authored by this blog’s humble overlord… that might be an oxymoron… and the Natural History Museum’s Paul Barrett (Naish & Barrett 2016). Dinosaurs has been well received and pretty successful in terms of sales, and so it came to pass that there was the need for a modified, softback version that included updates and corrections. Officially, the new version is a ‘fully revised and updated’ version, but it’s very literally a second edition, and that’s what I’m calling it.

Naish and Barrett, second edition - with a new cover!

First off, the production of a second edition – we’ll call it Dinosaurs 2nd ed (Naish & Barrett 2018) from hereon – allowed the correction of assorted typos and poor word choices. It never ceases to amaze me how much stuff we miss even when a given piece of text is checked, double-checked and checked again. Big thanks to fan of the book Klinsman Hinjaya for noting a number of required corrections. More importantly, said second edition also allowed us to update or modify various aspects of the science covered in the book. New data and new interpretations mean that our ideas on the biology and evolutionary history of extinct animals are constantly changing, and this was a great opportunity to get some of the relevant changes incorporated.

Some of you – especially those in possession of the first edition – are keen to know what’s different about Dinosaurs 2nd ed, so – without giving too much away – let’s take a look…

Caption: some of Emma’s drawings feature in the book. No, I’m kidding - they don’t. Or do they. Credit: Darren Naish.

A new cover. Personally, I think that Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved is a pretty good book, and I hope you agree. But I never much liked the cover, and I know I’m not alone. Given that it portrays a roaring monster that’s showing us the inside of its mouth and what biiiig teeth it has, it might be construed as being contrary to the message otherwise promoted throughout the book: that non-bird dinosaurs were animals, and not the monsters of Hollywood and popular fiction.

Caption: new cover art by Bob Nicholls of Paleocreations. I own a full-sized print of this amazing piece. Damn… I own a lot of Bob Nicholls art now. Credit: Bob Nicholls.

The plan for Dinosaurs 2nd ed was thus to produce a brand-new cover that better represented modern thinking on dinosaurs. Paul and I opted to have either a feathered theropod, or an unusual ornithischian, and we ended up going with the latter for reasons I can’t recall (I think because it might look weirder and less familiar: feathered theropods are so passé, after all). Our chosen artist – Bob Nicholls – came up with a bunch of test sketches, all depicting the Chinese heterodontosaur Tianyulong in various poses and behavioural settings. We chose one, and Bob went to extraordinary trouble to get the contrast, lighting and composition right. There’s much more to it than that but… ladies and gentlemen, I give you… our new cover.

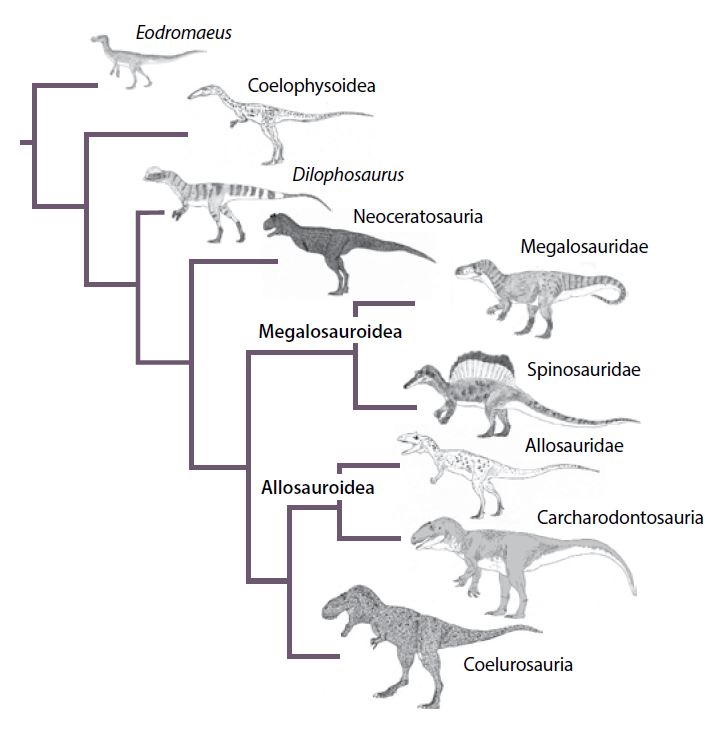

New artwork. Moving now to the insides of the book, we’ve also replaced a few other images that were used in the first edition. Bob has a few more of his excellent images in the book, we swapped out the (now defunct) diagrams on diplodocid jaw movement with a new reconstruction of a ground-feeding diplodocid (though illustrated without the keratinous beak recently proposed for this group), and Matt Martyniuk’s Anchiornis replaces a previous image with a problematic forelimb configuration. I also replaced a bunch of small images used in various of the cladograms.

Caption: some of the cladograms of Dinosaurs 2nd ed have been tweaked a little. This one depicts Theropoda, the predatory dinosaurs. Credit: Darren Naish.

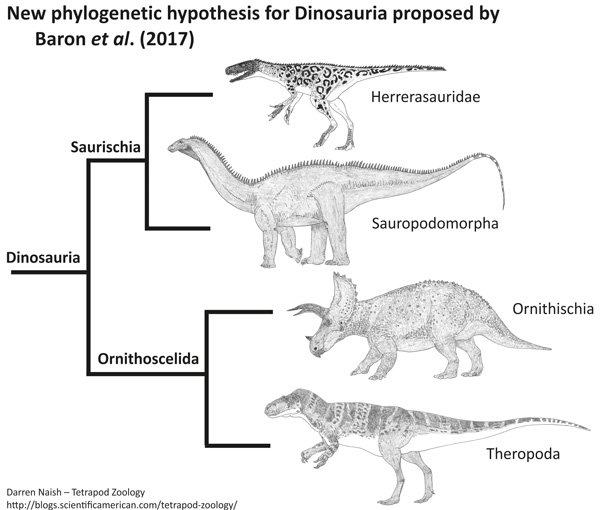

Necessary coverage of the Ornithoscelida thing. Currently, one of the most talked-about issues within the study of Mesozoic dinosaurs is Matt Baron et al.’s (2017) proposal that the main branches of the dinosaur family tree be rearranged, such that sauropodomorphs are outside a theropod + ornithischian clade termed Ornithoscelida. I wrote about this proposal when it was brand-new, back in March 2017. It has been hotly contested by several teams of authors and there are already a few publications saying how reanalysis does not support Baron et al.’s model, or at least does not support it preferentially above the others that are available.

Obviously, we just had to cover this issue for Dinosaurs 2nd ed – especially so given that Paul is one of the study’s authors – and a few new paragraphs of text and new diagrams summarise the area for our readers. Our coverage of the Ornithoscelida issue resulted in various knock-on changes elsewhere in the book. New phylogenetic positions, for example, have been favoured for herrerasaurids, Eoraptor and so on.

Caption: the Baron et al. model, as depicted in the 2017 article I wrote about it for TetZoo ver 2. Credit: Darren Naish.

New taxa, new names, new phylogenetic possibilities. The world of Mesozoic dinosaur phylogeny and systematics move fast – remember that an average year right now sees the naming of between 30 and 50 new non-bird dinosaur species. We’re at a stage where phylogenetic models are never really ‘overturned’, but they certainly undergo regular tweaking, modification and augmentation. In view of this, Dinosaurs 2nd ed includes references to Stenonychosaurus, Latenivenatrix (sorry, Troodon) and halszkaraptorines, and I subtly changed the wording on the megaraptorans…

Pisanosaurus is no longer bigged-up as a possible early ornithischian given data indicating that it’s a non-dinosaur.

Revising thoughts on the origins of flight. Those familiar with discussions on both bird and flight origins within dinosaurs will know all about the ‘trees down vs ground up’ argument, and also with the contention that it might be utterly wrong to polarise things in this way. Nevertheless, there remain – for all those attempts to point to shades of grey – extremes in the debate. My take on the earliest phases of maniraptoran flight has mostly involved a weird sort of hybrid whereby the animals concerned are deemed predominantly terrestrial but also capable of climbing, their leaping, fluttering and gliding in arboreal settings being antecedent to flight. Like many people, I was originally enthused enough by WAIR (wing-assisted incline running) to think that it might be a plausible explanation of how maniraptorans first came to exploit arboreal settings and, from there, evolve flight.

Caption: Dececchi et al. (2016) showed that at least some non-bird maniraptorans do not have the right combination of anatomical features to benefit from WAIR as originally envisioned. This work affected our thinking on flight origins in Dinosaurs 2nd ed. Credit: Dececchi et al. 2016, PeerJ

The diversity of non-bird maniraptorans is such that it looks likely that these animals practised all sorts of behaviours during the long time that they were around, and thus that various different acts and adventures could have contributed to their ability to leave the ground. Having said that, recent studies indicate that at least some of the relevant animals could likely leap into flight from a ground-based start (Dececchi et al. 2016), and – at the same time – that arboreal behaviour was unlikely in such species. The possibility that flight could well have evolved without any arboreal component is interesting (and even shocking to some), and sufficiently so that we’ve alluded to it (briefly) in Dinosaurs 2nd ed.

Caption: Dinosaurs, the Russian edition. Now I know what my name looks like in Russian. Yes, the title is not the same as the English one.

And that’s it. I should also add that Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved has also recently appeared in Australia (where it’s published by CSIRO), and that a Russian translation is now out as well. My thanks to everyone who’s bought this book, to those who commented on or said nice positive things about the first edition, and to everyone involved in its production and publication.

For those who haven’t purchased a copy, it’s available here from amazon, here from amazon.co.uk, and here from the publishers.

For previous articles relevant to this one, see…

Flight of the Microraptor, November 2013

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 1, May 2016

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 2: Meet the Maniraptorans, May 2016

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 3: Feathers Did Not Evolve in an Aerodynamic Context, May 2016

Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2016

Ornithoscelida Rises: A New Family Tree for Dinosaurs, March 2017

Refs - -

Baron, M. G., Norman, D. B. & Barrett, P. M. 2017. A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution. Nature 543, 501-506.

Naish, D. & Barrett, P. M. 2016. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. The Natural History Museum, London.