As we hurtle toward the end of the year – always a scary thing because you realise how much you didn’t get done in the year that’s passed – it’s time to look back at just a little of what happened in 2018. This article is not anything like a TetZoo review of 2018 (I’ll aim to produce something along those lines in early 2019), but, rather, a quick look at some of the year’s neatest and most exciting zoological (well, tetrapodological) discoveries. As per usual, I intended to write a whole lot more – there are so many things worthy of coverage – and what we have here is very much an abridged version of what I planned.

Animals we will meet below, a montage. Images: (c) Philippe Verbelen, (c) Kristen Grace, Florida Museum of Natural History, Graham et al. (2018), CC BY-SA 4.0.

Thanks as always to those supporting me at patreon. Time is the great constraint (and finance, of course), and the more support I have, the more time I can spend on producing blog content. Anyway, to business…

The Rote leaf warbler. New passerine bird species are still discovered on a fairly regular basis; in fact three were named in 2018*. One of these is especially remarkable. It’s a leaf warbler, or phylloscopid, endemic to Rote in the Lesser Sundas, and like most members of the group is a canopy-dwelling, insectivorous, greenish bird that gleans for prey among foliage. Leaf warblers are generally samey in profile and bill shape, so the big deal about the new Rote species – the Rote leaf warbler Phylloscopus rotiensis – is that its bill is proportionally long and curved, giving it a unique look within the group. It superficially recalls a tailorbird. Indeed, I think it’s likely that the species would be considered ‘distinct enough’ for its own genus if there weren’t compelling molecular data that nests it deeply within Phylloscopus (Ng et al. 2018).

* The others are the Cordillera Azul antbird Myrmoderus eowilsoni and the Western square-tailed drongo Dicrurus occidentalis.

A Common chiffchaff Phylloscopus collybita encountered in western Europe, a familiar Eurasian-African phylloscopid leaf warbler. Image: Darren Naish.

The story of the Rote leaf warbler’s discovery is interesting in that it’s yet another recently discovered species whose existence and novelty was suspected for a while. Colin Trainor reported leaf warblers on Rote in 2004 but never got a good look at them, Philippe Verbelen observed them in 2009 and realised how anatomically unusual they were, and it wasn’t until 2015 that a holotype specimen was procured (Ng et al. 2018). I’ve mentioned before the fact that documenting and eventually publishing a new species is rarely an instant see it catch it publish it event, but a drawn-out one that can take decades, and here we are again. Also worth noting is that the existence of a leaf warbler on Rote was not predicted based on our prior knowledge of leaf warbler distribution in view of the deep marine channel separating Rote from Timor and lack of any prior terrestrial connection. Yeah, birds can fly, but members of many groups prefer not to cross deep water channels. In this case, this did, however, happen and most likely at some point late in the Pliocene (Ng et al. 2018).

Rote leaf warbler in life, a novel member of an otherwise conservative group. Image: (c) Philippe Verbelen.

Rote has yielded other new passerines in recent years – the Rote myzomela Myzomela irianawidodoae (a honeyeater) was named in 2017 – and it’s possible that one or two others might still await discovery there.

Neanderthal cave art. Hominins don’t get covered much at TetZoo, which is weird given the amazing pace of relevant recent discoveries and the fact that they’re totally part of the remit. I mostly don’t cover them because I feel they’re sufficiently written about elsewhere in the science blogging universe, plus I tend to be preoccupied with other things. Nevertheless, I take notice, and of the many very interesting things published in 2018 was Hoffman et al.’s (2018) announcement of several different pieces of Spanish rock art, seemingly made by Neanderthals Homo neanderthalensis. The art concerned involves hand stencils, abstract lines, squares and amorphous patches of pigment, always marked in red.

Red abstract markings, discovered in several Spanish caves, are old, and in fact were seemingly made by hominins long before H. sapiens moved into Europe. The red sinuous marking and system of squares and lines near the middle of this photo are purported to have been made by Neanderthals (other images, depicting animals and present adjacent to these markings, were seemingly created more recently by H. sapiens individuals). Image: (c) P. Saura.

The main reason for the attribution of this art to Neanderthals is its age: uranium-thorium dating shows that it’s older than 64ka, which therefore makes it more than 20ka older than the time at which H. sapiens arrived in Europe (Hoffman et al. 2018). That seems compelling, and it’s consistent with a building quantity of evidence for Neanderthal cultural complexity which involves the use of shells, pigments, broken stalagmites and so on.

One of the most famous pieces of claimed Neanderthal rock art: the Gorham's Cave ‘hashtag’ from Gibraltar. Image: (c) Stewart Finlayson.

I should add here, however, that I’m slightly sceptical of the use of age as a guide to species-level identification. Why? Well, we have evidence from elsewhere in the fossil record that the range of a hominin species can be extended by around 100ka without serious issue (witness the 2017 announcement of H. sapiens remains from north Africa; a discovery which substantially increased the longevity of our species). In view of this, would a 20ka extension of H. sapiens’ presence in Europe be absolutely out of the question? Such a possibility is not supported by evidence yet, and I don’t mean to appear at all biased against Neanderthals.

A tiny Cretaceous anguimorph in amber, and other Mesozoic amber animals. As you’ll know if you follow fossil-themed news, recent years have seen the discovery of an impressive number of vertebrate fossils in Cretaceous amber, virtually all of which are from Myanmar and date to around 99 million years old. They include tiny enantiornithine birds, various feathers (most recently racquet-like ‘rachis dominated feathers’), the tiny snake Xiaophis, early members of the gecko and chameleon lineages and the small frog Electrorana. Many of these finds were published in 2018 and any one could count as an ‘amazing’ discovery.

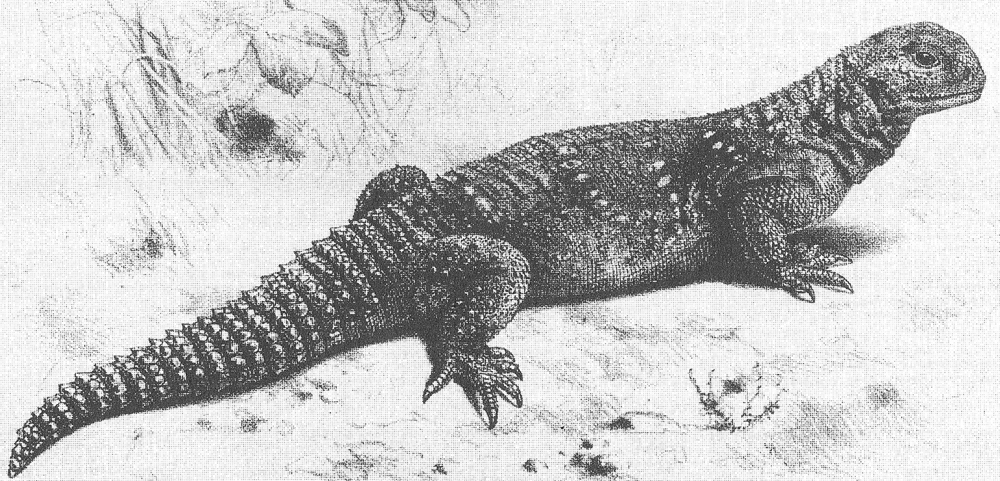

The Barlochersaurus winhtini holotype, from Daza et al. (2018).

However, there’s one fossil in particular that I find ‘amazing’, and it hasn’t received all that much coverage. It’s the tiny (SVL* 19.1 mm!), slim-bodied anguimorph Barlochersaurus winhtini, named for a single, near-complete specimen subjected to CT-scanning (Daza et al. 2018). Remarkable images of its anatomical details are included in Daza et al.’s (2018) paper. It has short limbs, pentadactyl hands and feet and a slim, shallow, bullet-shaped skull. Phylogenetic study finds it to be somewhere close to, or within, Platynota (the clade that includes gila monsters and kin, and monitors and kin), or perhaps a shinisaurian (Daza et al. 2018). It could be a specialised dwarf form, or somehow more reflective of the ancestral bauplan for these anguimorph groups. Either way, it’s exciting and interesting. What next from Burmese amber?

* snout to vent length

Barlochersaurus in life. It’s about the size of a paperclip. Image: (c) Kristen Grace, Florida Museum of Natural History (original here).

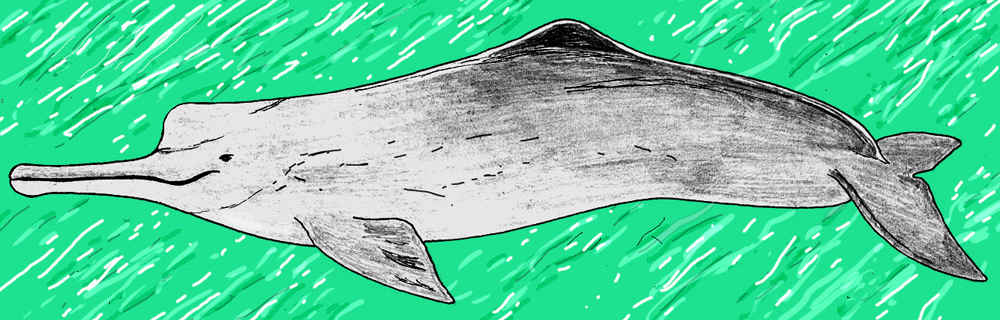

The Reticulated Siren. Sirens are very special, long-bodied aquatic salamanders with reduced limbs and bushy external gills. They’re very weird. They can reach 95 cm in length (and some fossil species were even larger), lack hindlimbs and a pelvis, have a horny beak and pavements of crushing teeth, and eat plants in addition to gastropods, bivalves and other animal prey. A longish article on siren biology and evolution can be found here at TetZoo ver 3.

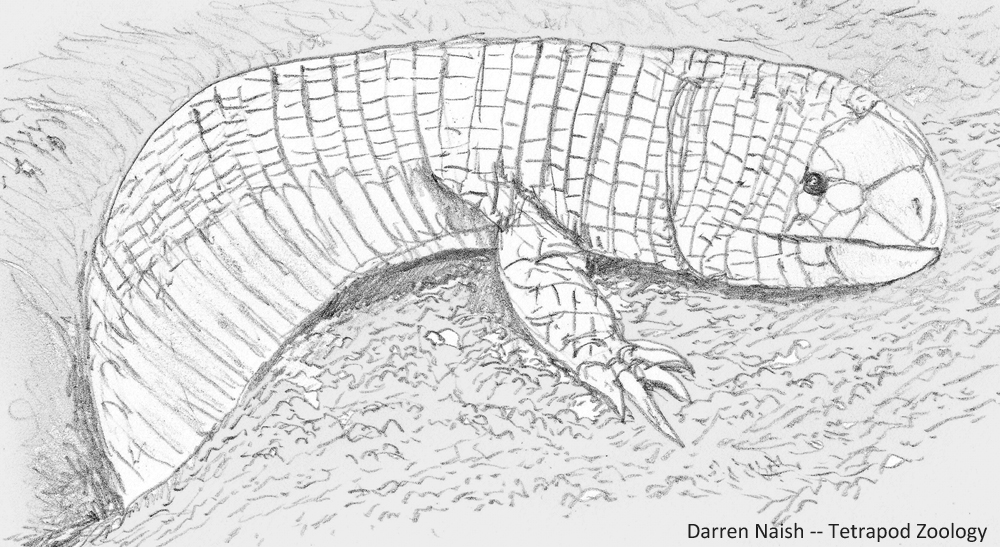

A life reconstruction of the Cretaceous siren Habrosaurus, showing features typical of the group. This animal could reach 1.5 m in total length. Image: Darren Naish (prepared for my in-prep texbook The Vertebrate Fossil Record, on which go here).

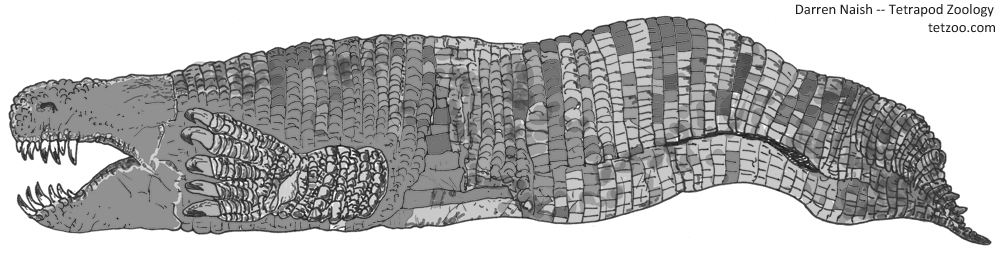

Until recently, just four living siren species were recognised. But it turns out that indications of a fifth – endemic to southern Alabama and the Florida panhandle – have been around since 1970 at least. Furthermore, they pertain to a big species, similar in size to the Great siren Siren lacertina. Known locally as the ‘leopard eel’ (a less than ideal moniker, given that there’s a real eel that already goes by this name), this animal has been published by Sean Graham and colleagues in the open-access journal PLoS ONE (Graham et al. 2018) wherein it’s formally christened the Reticulated siren S. reticulata. It reaches 60 cm in total length, has dark spots across its dorsal surface and a proportionally smaller head and longer tail than other Siren species.

A museum specimen of the species has been known since 1970 when its finder noted that it did “not conform” to descriptions of known species, and live specimens were collected by David Steen and colleagues in 2009 and 2014. Again, note that discovery and recognition was a drawn-out process. The discovery has, quite rightly, received a substantial amount of media coverage, and many interesting articles about the find are already online. Many of you will already know of David Steen due to his social media presence and Alongside Wild charity (which I’m proud to say I support via pledges at patreon).

The Reticulated siren paratype specimen, as described by Graham et al. (2018). Image: Graham et al. (2018), CC BY-SA 4.0. Original here.

The idea that a new living amphibian species 60 cm long might be discovered anew in North America in 2018 is pretty radical. I’m reminded of the 2009 TetZoo ver 2 article ‘The USA is still yielding lots of new extant tetrapod species’ (which is less fun to look at than it should be, since images aren’t currently showing at ver 2). Furthermore, Graham et al. (2018) discovered during their molecular phylogenetic work that some other siren species are not monophyletic but likely species complexes, in which case taxonomic revision is required and more new species will probably be named down the line.

And that’s where I must end things, even though there are easily another ten discoveries I’d like to write about. This is very likely the last article I’ll have time to deal with before Christmas. As I write, I’m preparing to leave for the Popularising Palaeontology conference which happens in London this week (more info here), and then there are Christmas parties and a ton of consultancy jobs to get done before the New Year. On that note, I’ll sign off with a festive message, as is tradition. Best wishes for the season, and here’s to a fruitful and action-packed 2019. Special thanks once again to those helping me out at patreon.

For previous TetZoo articles relevant to various of the subjects covered here, see…

The USA is still yielding lots of new extant tetrapod species, July 2009

THE AMAZING WORLD OF SALAMANDERS, October 2013

Chiffchaffs: a view of passerines from the peripheries (part I), August 2014

The Biology of Sirens, June 2016

Refs - -

Daza, J. D., Bauer, A. M., Stanley, E. L., Bolet, A., Dickson, B. & Losos, J. B. 2018. An enigmatic miniaturized and attenuate whole lizard from the mid-Cretaceous amber of Myanmar. Breviora 563, 1-18.

Hoffman, D. L., Standish, C. D., García-Diez, M., Pettitt, P. B., Milton, J. A., Zilhão, J., Alcolea-González, J. J., Cantelejo-Duarte, P., Collado, H., de Balbín, R., Lorblanchet, M., Ramos-Muñoz, J., Weniger, G.-Ch. & Pike, A. W. G. 2018. U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neandertal origin of Iberian cave art. Science 359, 912-915.

![Today, I’m the proud owner of a PalaeoPlushies thylacine - a Christmas 2017 gift from my mother-in-law, Sheila. He’s called Kid Cynoceph and I love him. Buy your own here! [UPDATE: currently sold out!] Image: Darren Naish.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/510be2c1e4b0b9ef3923f158/1544108376632-2UTKGZX7U96NM2YOIUQ6/Tet-Zoo-12th-birthday-palaeoplushies-thylacine-Dec-2017-600-px-tiny-May-2018-Darren-Naish-Tetrapod-Zoology.jpg)