Hello faithful and noble readers. Recall the unfinished series on EXTREME CETACEANS? Today we continue with the next episode in said series.

Caption: Stenella longirostris, Phocoena dioptrica and Sousa chinensis, three of the cetacean species covered in the previous parts of this series. Image: Darren Naish.

If you don’t know what the deal is here, it’s that I’m writing about those cetaceans which I consider ‘extreme’, this meaning that they’re “weird, possessing anatomical specialisations and peculiarities that are counter-intuitive and little discussed, and most likely related to an unusual ecology, physiological regime, feeding strategy or social or sexual life”, to quote the first article in the series. And thus we get on with it…

Right whale dolphins. Many dolphin species are aesthetically pleasing because they’re of a beautifully streamlined, attenuate shape, and because they have clean, tidy colour schemes where contrasting blocks of colour are neatly separated, and sometimes augmented or marked by parallel, sweeping lines. This combination – an attenuate, streamlined form and a tidy, well-demarcated colour scheme – is carried to an extreme in the two Lissodelphis species, or right whale dolphins.

Caption: Alcide Dessalines d'Orbigny’s 1847 illustration of the Southern right whale dolphin Lissodelphis peronii. The species is named for naturalist François Peron, the first European to report a sighting of this species. Image: public domain (original here).

Right whale dolphins are mid-sized as dolphins go (about 2-3 m long), short-beaked, and incredibly attenuate. Their pectoral flippers and tail flukes are small, a dorsal fin is absent, and the tailstock tapers to a ridiculous degree. They also have the flashiest, tidiest colour scheme of black and white. They look nothing like the enormous, super-bulky right whales, but do resemble them in lacking a dorsal fin. They’re also incredibly fast, among the fastest of all cetaceans,

Caption: a Southern right whale dolphin group, photographed in 2008. These dolphins are often seen in large groups of 100 individuals or more. Image: Lieutenant Elizabeth Crapo, NOAA Corp, public domain (original here).

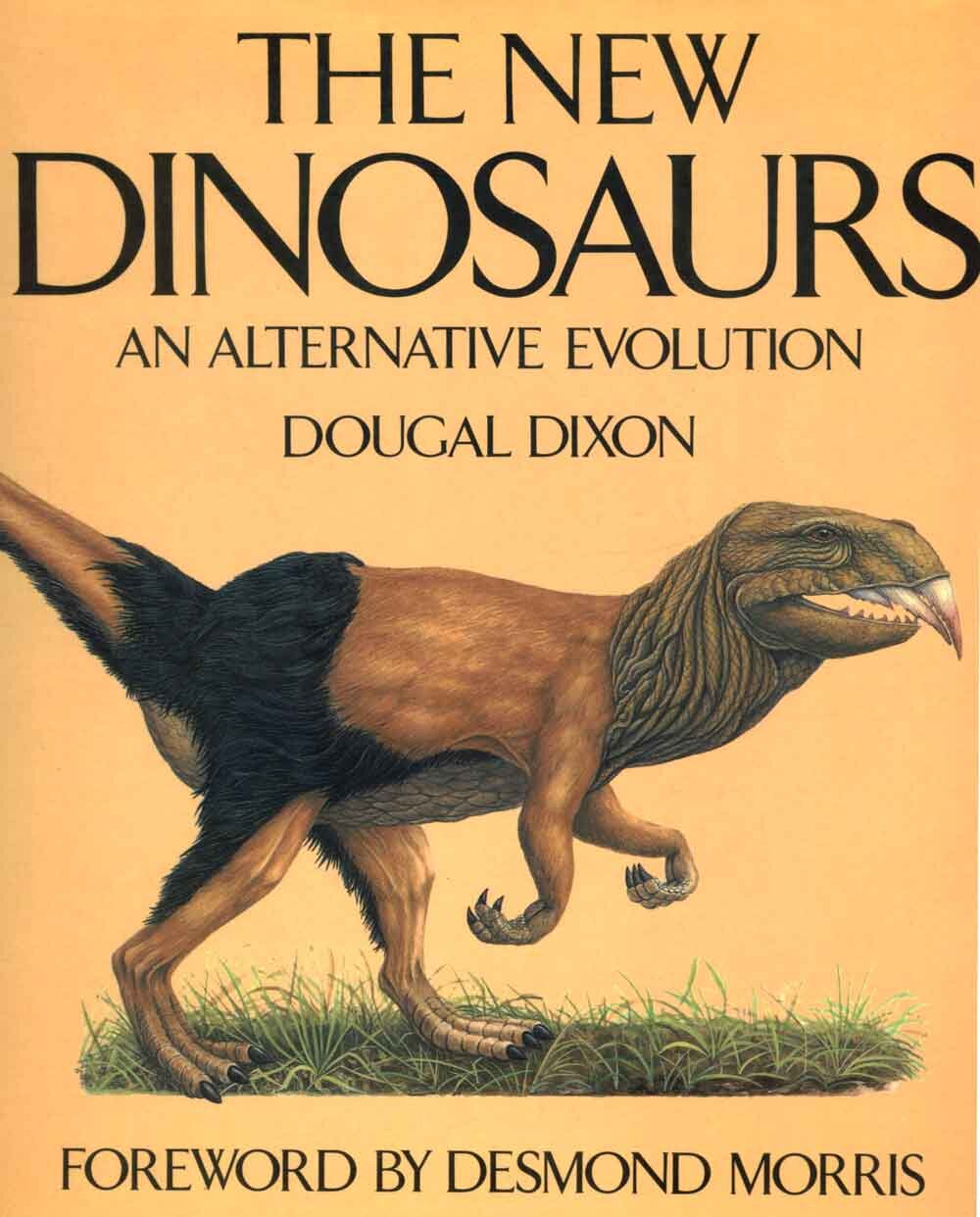

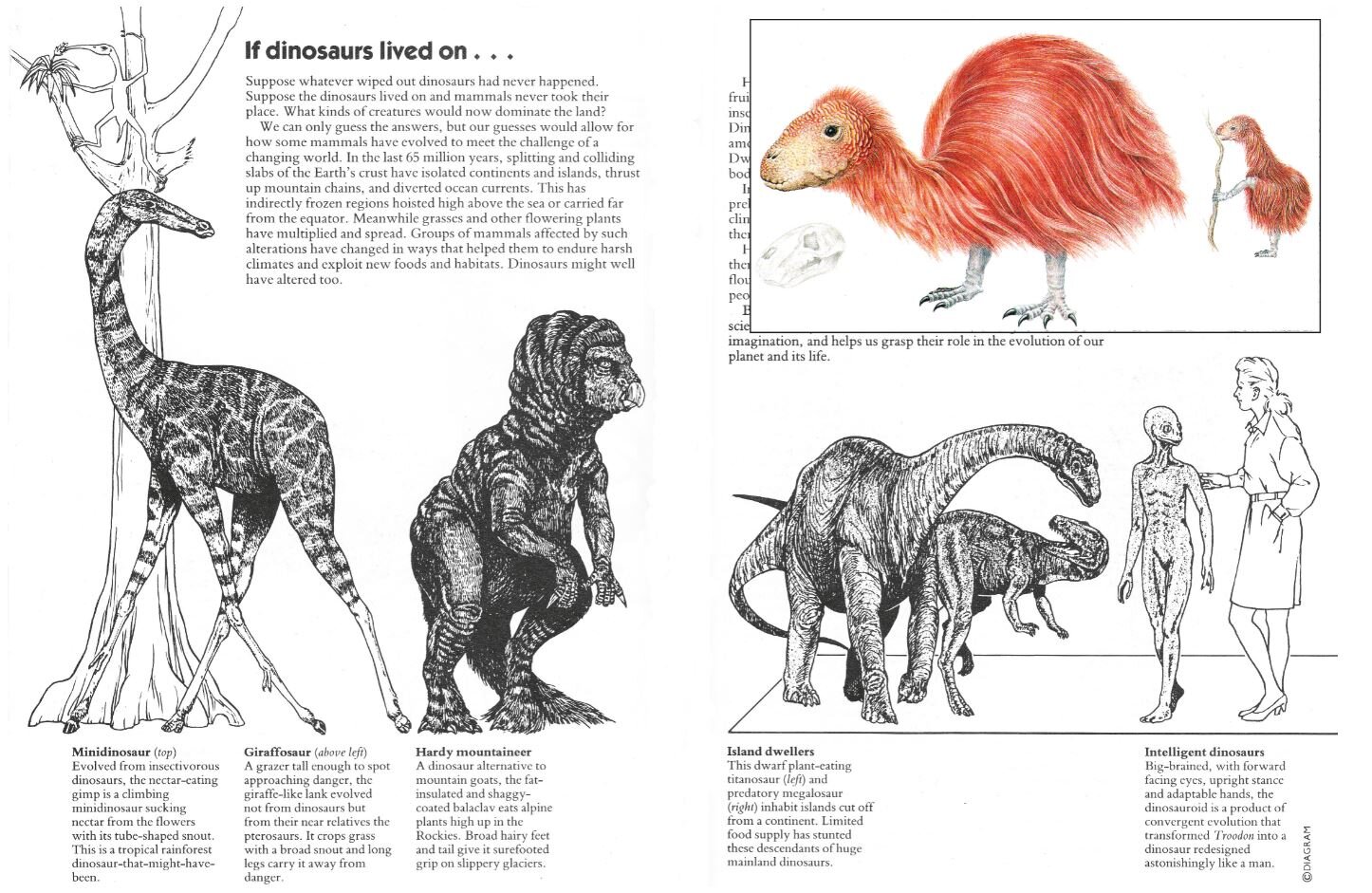

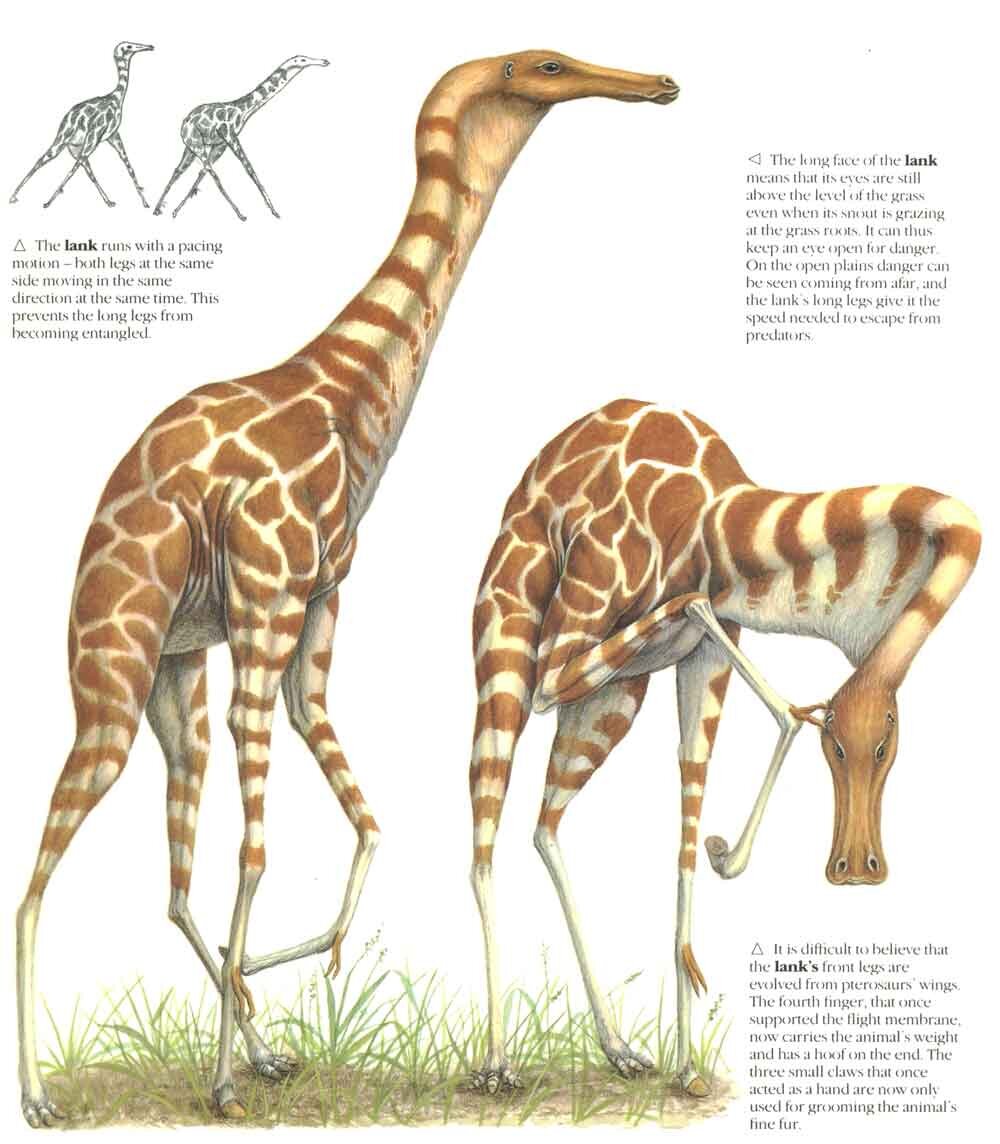

Right whale dolphins, incidentally, are close kin of lags (the Lagenorhynchus and Sagmatias dolphins) and probably of the small, short-beaked Cephalorhynchus dolphins (the most familiar of which is the piebald Commerson’s dolphin C. commersoni) (McGowen et al. 2009). But in my headcanon they’re either miniaturised, late-surviving basilosaurids, or whale-mimicking, fully aquatic penguins that have time-travelled from the Dixonian Era to the present. Look at the pictures here and you’ll see what I mean.

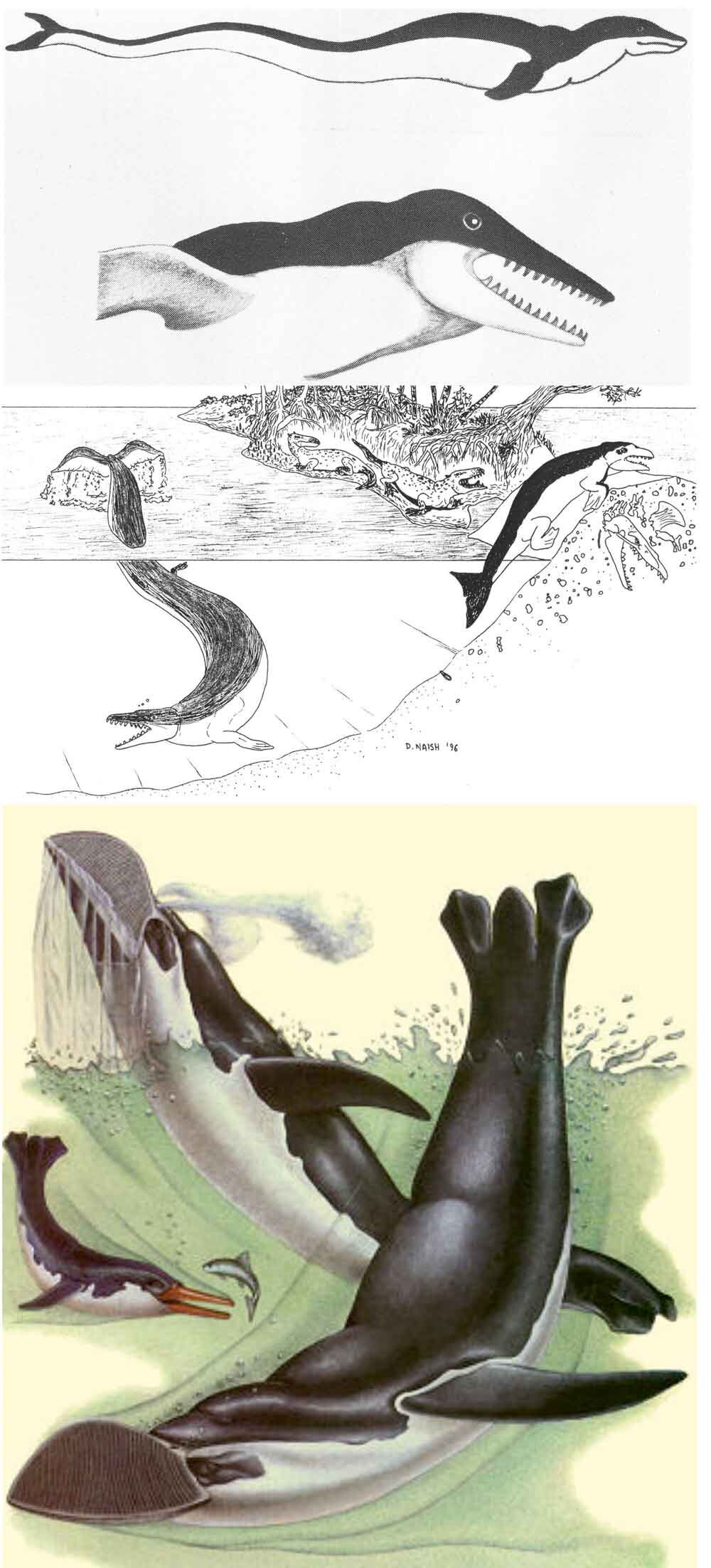

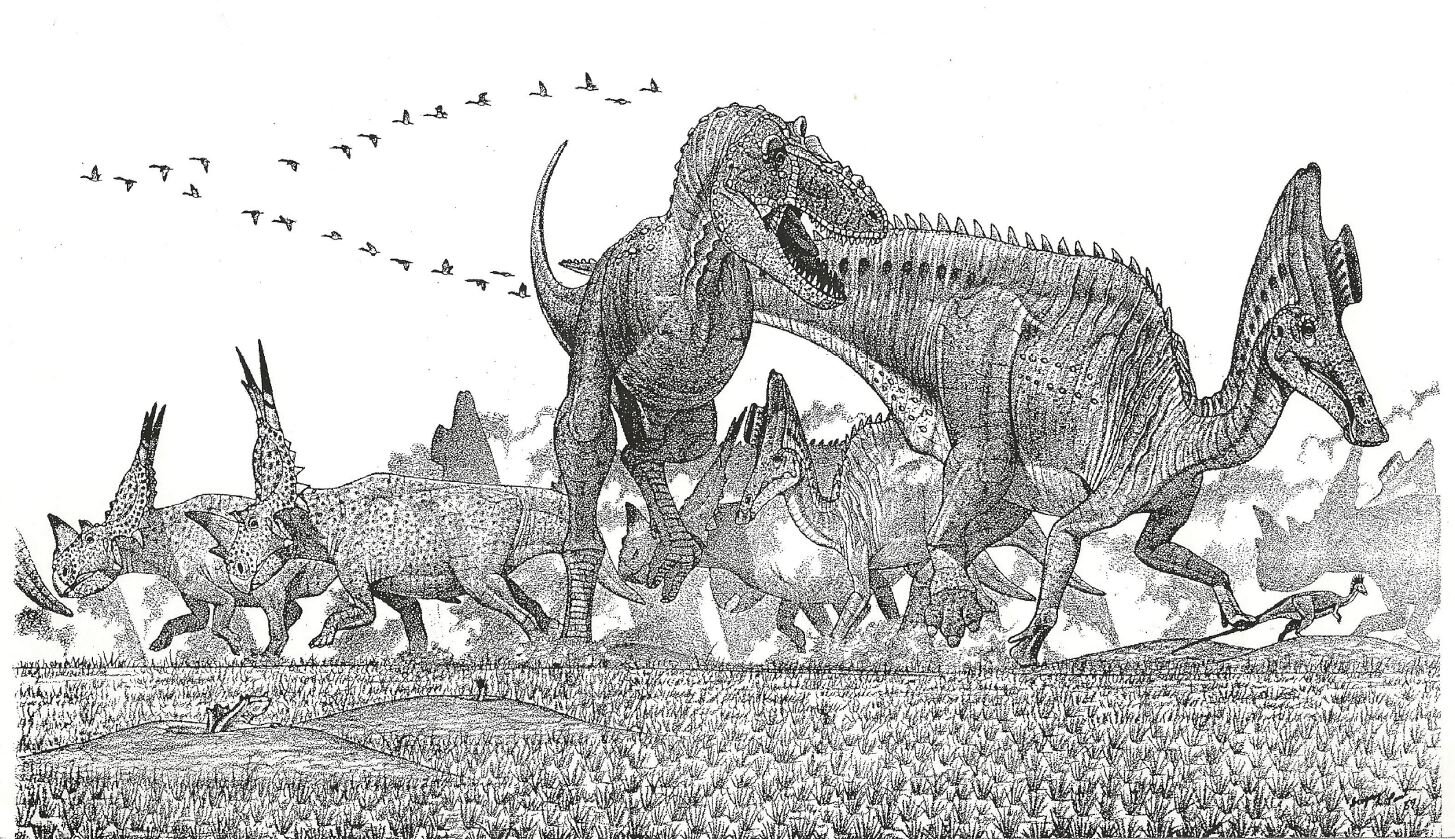

Caption: old depictions of basilosaurs and other archaeocetes – those at top are from McEwan (1978) and Naish (1996) – reveal that right whale dolphins are actually descendants of a lineage outside of Neoceti. Or perhaps they’re future penguins, like the Vortex (from Dixon 1981). Images: McEwan (1978) and Naish (1996), Dixon (1981).

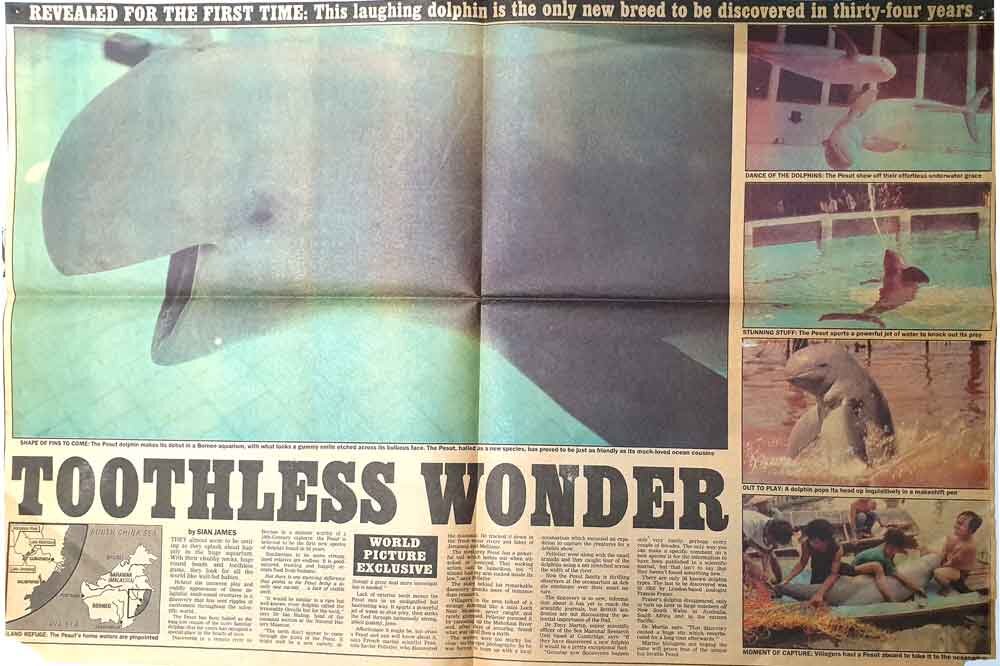

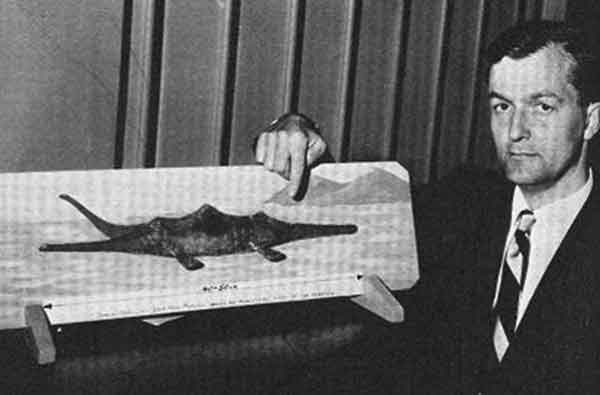

The Pesut. In 1989, I thought I knew all the extant cetacean species known to science at the time. So I was blown away when the Today newspaper, which I used to read, ran a two-page feature on a very odd cetacean which was touted as “the only new breed to be discovered in thirty-four years”, this being a reference to the number of years that had elapsed since the scientific naming of Fraser’s dolphin Lagenodelphis hosei in 1956. Evidently, the article was reporting a proposal – seemingly originating with Francois-Xavier Pelletier – in which the cetacean concerned was being considered a potential new species. Grey, toothless and prone to squirting jets of water for fun, it was said to be a freshwater inhabitant of Borneo’s Mahakam River, and was dubbed the Pesut. The what?

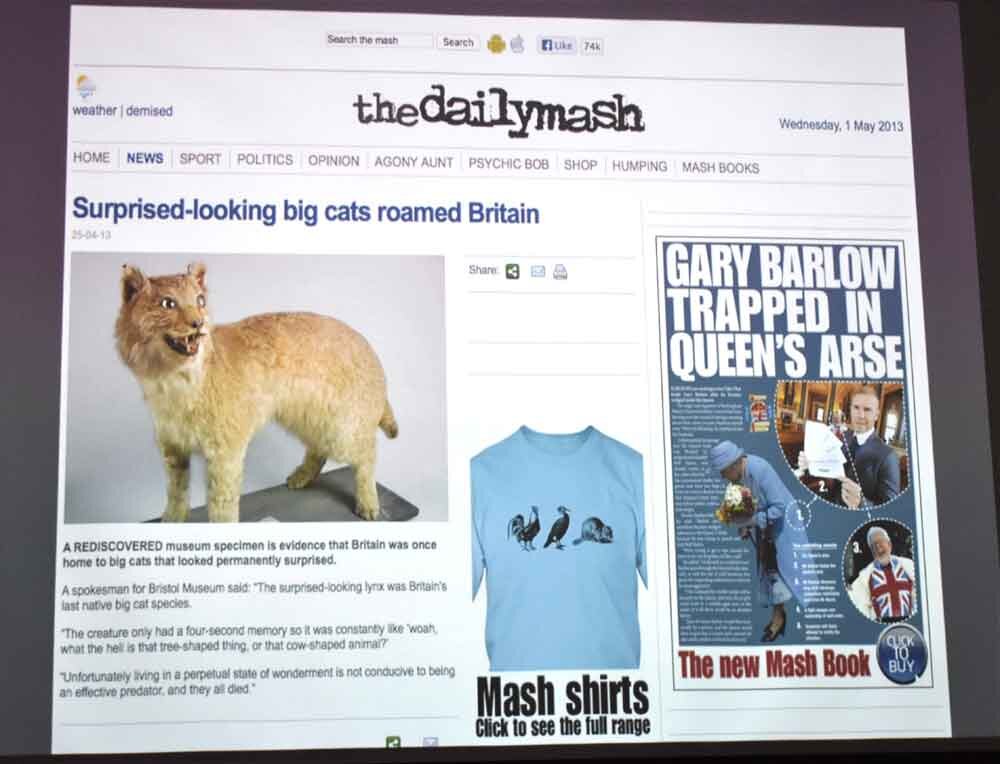

Caption: a Today newspaper article of 1989 reports ‘the Pesut’ as a new kind of dolphin. I regret that I don’t have the complete citation for this article; in my wisdom I clipped the date and other details at some point. Readers with exceptional memories might recognise the photo at upper right as the inspiration for a SpecZoo-themed piece of art…

Today, the Pesut isn’t regarded as a distinct species, but a local variant of the Irrawaddy dolphin Orcaella brevirostris. It’s known locally as the Pesut Mahakam, more formally as the Mahakam River dolphin, and is seemingly – with the rest of the Orcaella dolphins – an early-diverging member of the globicephaline clade (McGowen et al. 2009, Vilstrup et al. 2011), otherwise known for including killer whales, pilot whales and kin, the ‘blackfish’ [UPDATE: killer whales no longer appear to be part of Globicephalinae; see comments]. Pelletier’s proposal that the Mahakam River Orcaella population might be distinct is odd, since anyone familiar with the historical taxonomy of Orcaella knows (or should have known, even in 1989) that Pesut Mahakam is a local name for some riverine populatons of O. brevirostris (Marsh et al. 1989). Furthermore, there’s a long history of riverine Orcaella populations being considered distinct and of having their taxonomic status tested and re-evaluated.

Caption: an Irrawaddy dolphin photographed in Cambodia. Image: Stefan Brending, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

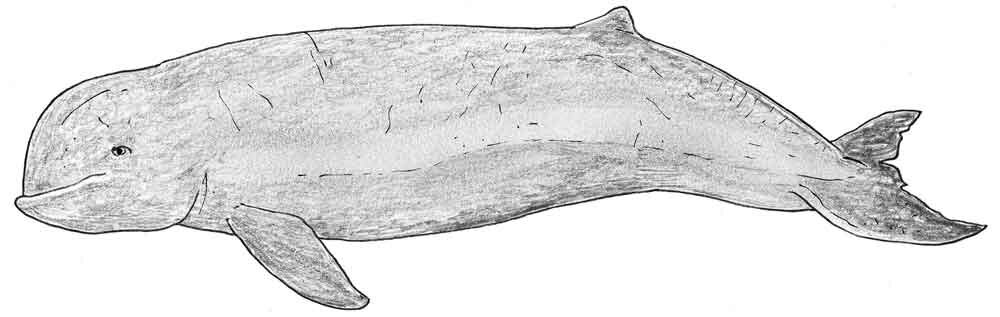

Whatever, the Pesut does look kinda unusual. Books on whales very often say or imply that the Boto or Amazon river dolphin Inia geoffrensis and Beluga Delphinapterus leucas are the only two living cetaceans with an especially mobile neck, but this very probably isn’t true and Pesuts are often shown with the head being held at an obvious angle relative to the body. Other weird features that make the Pesut ‘extreme’ are its globular, short-snouted face and smiling mouthline, and the crease that runs along part of its dorsal midline.

Caption: an effort to portray an Irrawaddy dolphin in life. This dolphin can reach 2.75 m in length, males being larger. Image: Darren Naish.

If you know anything about cetaceans you’ll be aware of the fact that the Irrawaddy dolphin is superficially similar to the Beluga, and it’s this similarity which has led to the occasional suggestion that Orcaella might not be a dolphin but a tropical member of the same family as the Beluga (Monodontidae). This isn’t a ridiculous idea, but it isn’t supported by the detailed anatomy of this animal, or by molecular data.

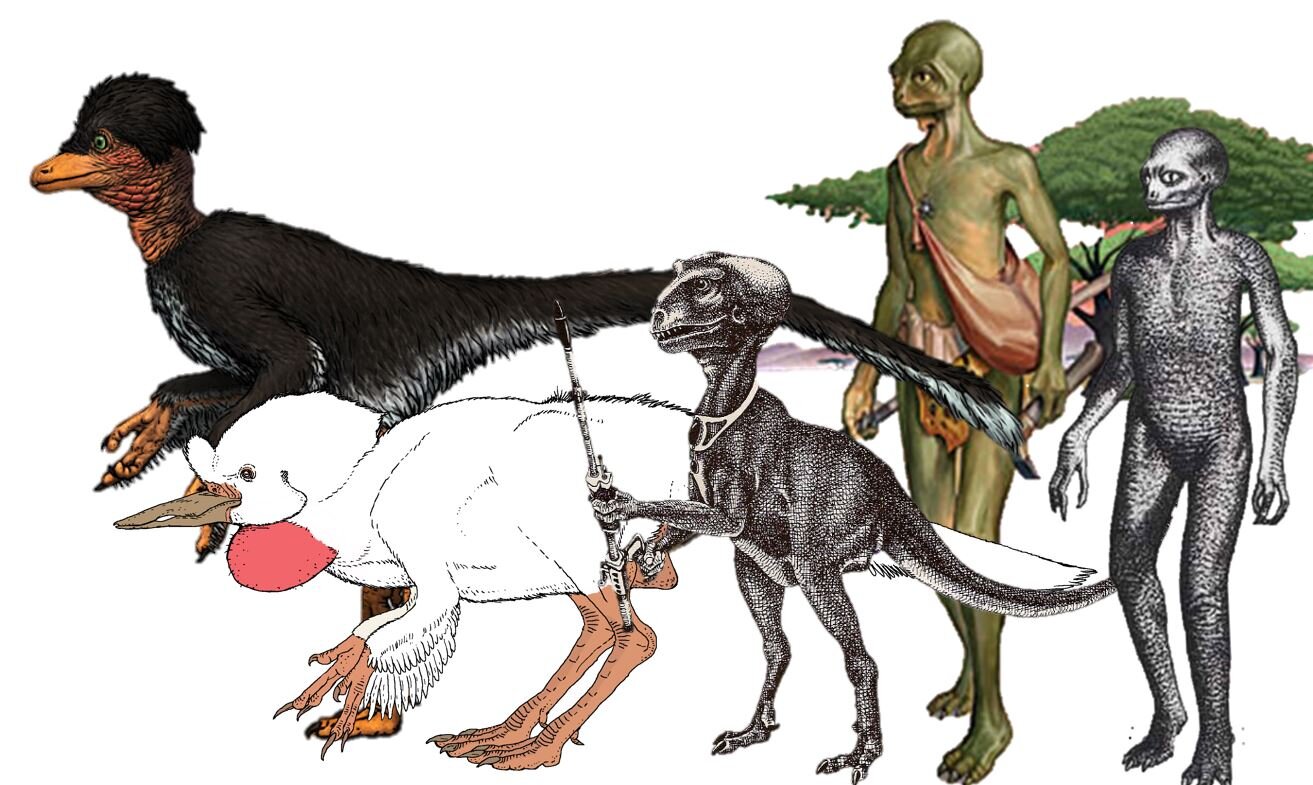

Caption: I said the montage would become increasingly cluttered. And we’re not done yet. Image: Darren Naish.

And that’s where we’ll end things for now; the next article in the series will appear soon. And I’ll publish a lot more on whales here in the future. Here’s some of the stuff that exists in the archives (as always, much of the material at TetZoo versions 2 and 3 has been ruined by the removal of images, so I’m linking to wayback machine versions)…

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008

Scaphokogia!, July 2008

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015

Whale Watching in the Bay of Biscay, August 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 1, September 2019

Extreme Cetaceans, Part 2, September 2019

Refs - -

Dixon, D. 1981. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Granada, London.

Marsh, H., Lloze, R., Heinsohn, G. E. & Kasuya, T. 1989. Irrawady dolphin Orcaella brevirostris (Gray, 1866). In Ridgway, S. H. & Harrison, R. (eds) Handbook of Marine Mammals Volume 4. Academic Press (London), pp. 101-118.

McGowen, M. R., Spaulding, M., Gatesy, J. 2009. Divergence date estimation and a comprehensive molecular tree of extant cetaceans. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 53, 891-906.

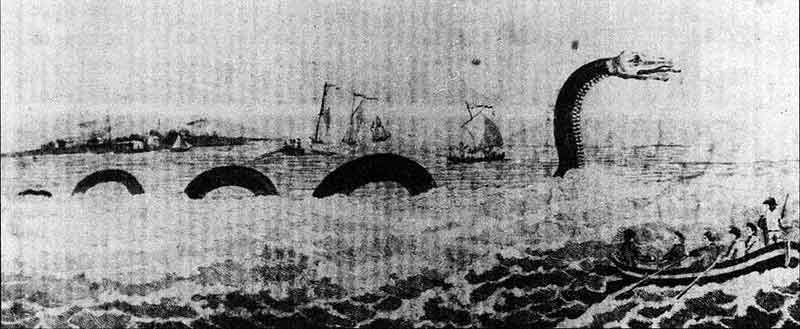

Naish, D. 1996. Ancient whales, sea serpents and nessies part 2: theorising on survival. Animals & Men 10, 13-21.

Vilstrup, J. T., Ho, S. Y., Foote, A. D., Morin, P. A., Kreb, D., Krützen, M., Parra, G. J., Robertson, K. M., de Stephanis, R., Verborgh, P., Willerslev, E., Orlando, L. & Gilbert, M. T. P. 2011. Mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses of the Delphinidae with an emphasis on the Globicephalinae. BMC Evolutionary Biology 11: 65.