Welcome to 2024! And we kick things off with frogs. What, I hear you ask, is a strabomantid?

Caption: a hyloid montage. What is that small creature in the red circle? It’s a terraranan, and it’s here to shake things up…

Strabomantids are a group of terrestrial South and Central American frogs, sometimes termed terrestrial-breeding frogs, landfrogs or cloud forest landfrogs. Just about all are small (20-50 mm SVL*), direct-developing animals associated with forests. They’re mostly animals of the forest floor, but some are arboreal. Some strabomantids (like the pristimantine Serranobatrachus) are cloud-forest animals that hide in leaf litter whereas others (like Yunganastes and Atopophrynus) have some association with moss-covered rocks. The term ‘direct-developing’ refers to the reproductive strategy where no tadpole phase exists, and where fully-formed miniature froglets emerge directly from eggs. Oh, before I continue, let me say that I thought I’d written about the group on Tet Zoo before, but I can’t find anything in the archives, ho hum.

* SVL = snout to vent length. Body length, basically.

Strabomantid anatomy. As is typical for animal groups whose members are mostly regarded as allies on the basis of molecular data (read on), it’s difficult at this point in history to point to anatomical traits that might be regarded as diagnostic for this group. We can at least make some generalisations about them though.

Caption: two representatives of Strabomantidae, demonstrating typical morphology for the group. At left, Two-lined robber frog Bahius bilineatus, a holoadenine that occurs across the Brazilian state of Bahia and is predicted to occur in Minas Gerais as well. At right, Savage’s goias frog Barycholos ternetzi of central Brazil. Barycholos is also a holoadenine. Images: Rafael O. Abreu, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here); Lucas Grandinetti, CC BY-SA 2.5 (original here).

Slightly expanded digital pads are typical for strabomantids, and these are expanded into proper discs in arboreal species (including those included in Pristimantis and Strabomantis). These discs are supported internally by hook-like lateral processes on the terminal phalanges, and T-shaped and knob-bearing phalanges are also present in the group (Hedges et al. 2008). The fingers are unwebbed, and the toes usually are too, though the toes do sometimes have webbing at their bases. The fourth finger is reduced and even absent in some taxa. A single, medially located vocal sac is generally present but some (like Holoaden) lack it.

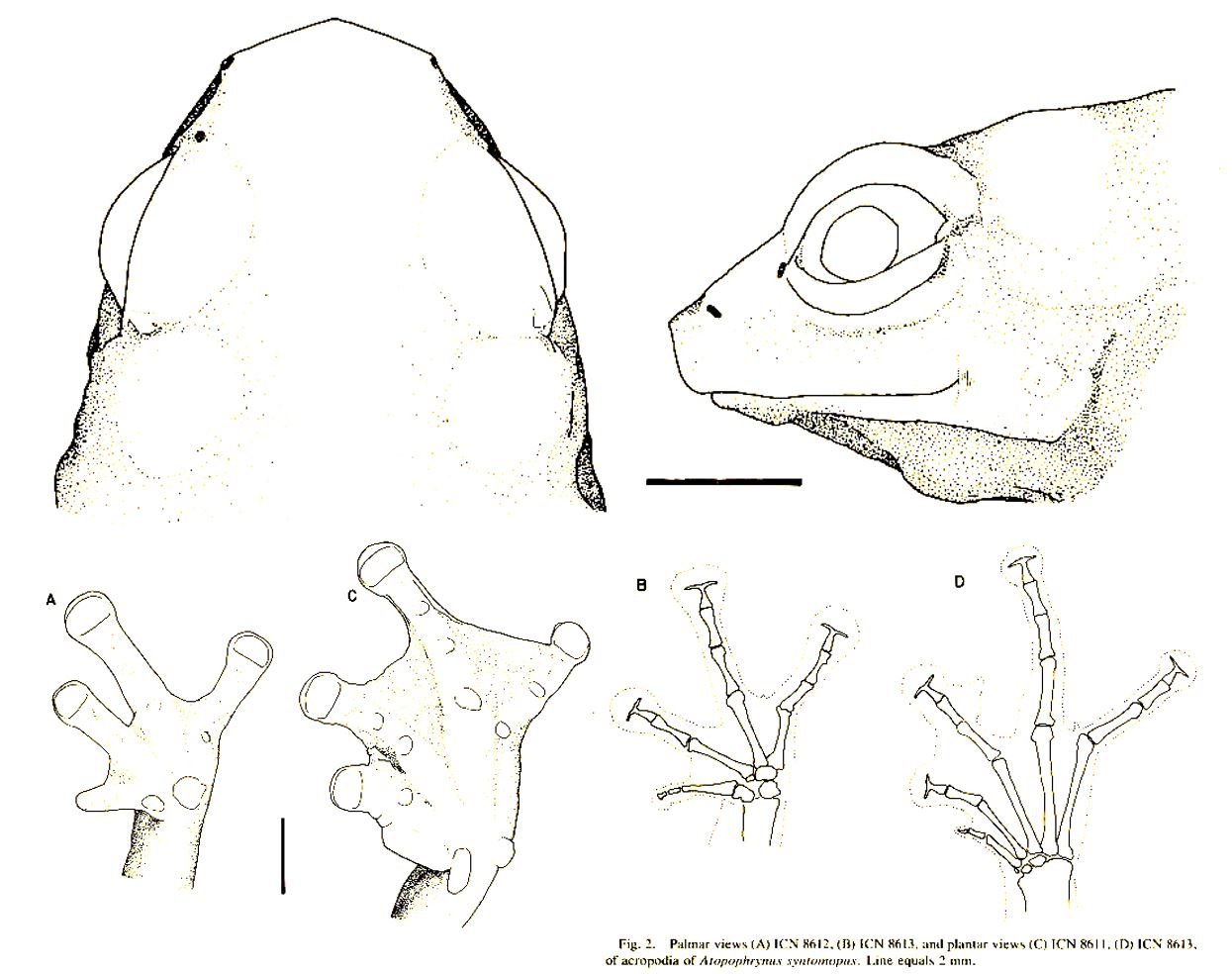

External ears are generally present in these frogs, but some (like the mostly Andean Bryophryne species and the possibly extinct Sonson frog Atopophrynus syntomopus of Colombia) lack them. Atopophrynus, incidentally, was originally described as a poison-dart frog (Lynch & Ruiz-Carranza 1982). I say that it’s possibly extinct because no specimens have been discovered since the type specimens were collected in 1981, and this is despite repeated searching at the type locality.

Caption: images of the Sonson frog Atopophrynus syntomopus from the original description. In the head, note the lack of features around the ear region. In the figures of the hands (A and B) and feet (C and D), note the strongly reduced first toe (C and D) and the T-shaped distal phalanges. This frog is tiny: the scale bars are 2 mm. Images: Lynch & Ruiz-Carranza (1982).

Pristimantis, final boss of tetrapod genera. Strabomantids might not be familiar, but they really should be, since one of the most noteworthy features of the group is that it includes the most speciose tetrapod genus of all time, this being Pristimantis, named by Spanish herpetologist Marcos Jiménez de la Espada back in 1870. As of the time of writing (January 2024), 602 species in this genus are recognized. As you might guess for such a speciose group, new species are named on a regular basis: 12 new Pristimantis species were named in 2023, for example. Pristimantis species tend to be large-eyed, slim-limbed little frogs marked with small spots or fine striping on their dorsal surfaces. There’s a fair amount of variation in snout shape and skin texture, some being smooth-skinned, others being bumpy or granular. Some are named rainfrogs (also written rain frogs), rubber frogs and robber frogs. These names are apparently all onomatopoeic references to their calls and nothing to do with anatomy or behaviour.

Caption: a very useful figure from Hedges et al. (2008), highlighting the continual rise over time in our knowledge of strabomantids and their kin, the terraranan frogs. This figure also makes the point that a small number of experts have driven this trend. It’s important to remember that this sort of thing (which is common across taxonomic groups) reflects actual discovery, not fashion or novel approaches to taxonomy (as is sometimes argued). Image: Hedges et al. (2008).

A good many Pristimantis species were originally included in Eleutherodactylus, a genus whose affinities actually lie elsewhere within Hyloidea. That is, it’s not a strabomantid. There always was a suspicion that the traditional version of Eleutherodactylus was what we in the trade term a taxonomic wastebasket – it was a dumping ground for small, anatomically nondescript Neotropical hyloids that couldn’t be tidily allocated to any of the familiar hyloid groups – and molecular data accrued during the 21st century has demonstrated that this is indeed the case (Frost et al. 2006, Hedges et al. 2008). There’s a lot to say on the dissolution of Eleutherodactylus and what’s happened to its constituent parts but this isn’t the place for that.

Caption: a montage of Pristimantis species. So pretty! The species shown here are (clockwise from upper left) P. orcesi, P. erythros, P. loujosti and P. pycnodermis. These species were figured together in the 2018 description of P. erythros of the Ecuadorian Andes, named therein the Blood rain frog! Image: Sánchez-Nivicela et al. (2018).

Some select strabomantids with unusual names. Including the Sonson frog, 20 currently recognized genera are included within Strabomantidae. In addition to those I’ve already mentioned, it’s worth making comments on a few of the others… though not all of them, or I’ll never get this article finished. I’ve opted here to discuss those taxa whose names catch my eye.

Caption: representative strabomantids showing some of the variation in head size and shape. At left, Noblella pygmaea, a tiny Peruvian species named in 2009. At right, the Common big-headed frog Oreobates quixensis, a relatively large and short-snouted member of its genus. Images: Alessandro Catenazzi, CC BY-SA 2.5 (original here); Pavel Kirillov, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

Euparkerella was named in 1959 in honour of British herpetologist H. W. Parker and contains small, narrow-headed, short-fingered frogs of the Brazilian Atlantic forest. Molecular studies indicate that substantial cryptic diversity exists within this genus and that much micro-endemism is present (Fusinatto et al. 2013), so more species are set to be named in coming years. Holoaden is another endemic Brazilian genus (named in 1920 by Brazilian herpetologist Alìpio de Miranda-Ribeiro), its species notable for their association with highland, mountainous environments and for a highly glandular dorsal surface.

Caption: Euparkerella brasiliensis, photographed in Rio de Janeiro State. Image: Fusinatto et al. (2013), CC BY 4.0 (original here).

Niceforonia, a close relative of Holoaden according to molecular data (Padial et al. 2014), is named for Colombian herpetologist Nicéforo María and includes 15 species endemic to northern South America. This is one of those taxa where the terminal phalanges (the bones at the tips of the digits) are T-shaped. Lynchius is another relative of Holoaden (according to some studies; see Pyron & Wiens 2011), and again its name commemorates a herpetologist noted for his work on tropical American amphibians, this time John D. Lynch. At least 11 frog and salamander taxa have been named in Lynch’s honour so far.

Finally, Qosqophryne was named in 2020 for species previously included in Bryophryne and is endemic to the Department of Cusco in Peru. Its generic name uses the Quechua spelling – Qosqo – of Cusco (combined with phryne, Greek for ‘frog’) (Catenazzi et al. 2020).

Where do strabomantids fit in the anuran family tree? There’s no doubt that strabomantids are hyloids: that is, part of the major clade that includes glassfrogs, treefrogs, true toads, poison-dart frogs and many others. Within that clade, molecular studies indicate that strabomantids are part of the clade that also includes the craugastorid fleshbelly frogs and kin, the eleutherodactylid New World rain frogs and the sometimes toxic brachycephalid toadlets and robber frogs. This massive clade – containing over 1000 species – is termed either Terrarana or Brachycephaloidea and a substantial amount of work has been published on its phylogeny, taxonomy and diversity since about 2008 (e.g., Hedges et al. 2008, Pyron & Wiens 2011, Canedo & Haddad 2012, Padial et al. 2014, Heinicke et al. 2018, Motta et al. 2021).

Caption: I’ve published hyloid cladograms several times here at Tetrapod Zoology, and this is the most recent version, dating to 2017 and produced to accompany an article on poison-dart frogs. It depicts a sort of consensus based on the cladograms of Frost et al. (2006), Grant et al. (2006) and Pyron & Wiens (2011), with the taxonomy proposed by Frost et al. (2006) superimposed on to the branches. Note that ceratophryids (horned frogs) are depicted as being close to bufonids (true toads) and dendrobatids (poison-dart frogs). And where are terraranans? I excluded them entirely. Image: Darren Naish, images produced for the textbook.

Caption: several new hyloid cladograms have been published since I produced the version shown above. They differ sufficiently in details that it’s hard to produce a consensus: this is a simplified version of the consensus featured at AmphibiaWeb. Note the unresolved polytomy that includes terraranans and kin. The topology shown here differs sufficiently from that of Frost et al. (2006) that the names they proposed (including Leptodactyliformes and Agastorophrynia) have, potentially, very different memberships from the ones they preferred, and for that reason I haven’t bothered applying them here. Image: Darren Naish, images produced for the textbook.

The taxonomic history of terraranans is hopelessly complicated and the hypothesis that they form a clade composed of multiple ‘family’-level groups is recent, effectively starting with a study published by S. Blair Hedges and colleagues in 2008. That 2008 study is also the one in which the group name Strabomantidae was first coined. Hedges et al. (2008) didn’t provide anything like a phylogenetic definition for Strabomantidae but did list 49 character states that they used to help define this group. Many of these are references to the absence of unusual features present in other terraranan groups (like the vertebral shields and fusion between the skull bones and overlying skin present in some brachycephalids), and working out which are truly diagnostic for strabomantids specifically would be a lot of work.

Caption: brachycephalid frogs – sometimes called three-toed toadlets – have been mentioned a few times in this article, and this is what they look like. Fairly hilarious. Also quite extreme in anatomical terms. The species shown here are (left) Brachycephalus izecksohni and B. olivaceus, both from Brazil and both named anew in 2017. Images: Ribeiro et al. (2017), CC BY-SA 4.0.

Within Terrarana/Brachycephaloidea*, some variation in results means that authors have disagreed on which taxonomy best reflects phylogeny. Things will become needlessly complicated if I recount all the to and fro that’s happened in the literature, but I’ll make my life easier by saying that I’m following those authors (e.g., Hedges et al. 2008, Blackburn & Wake 2011, Heinicke et al. 2018, Jetz & Pyron 2018, AmphibiaWeb 2024) who find a topology where Strabomantidae and the closely related Craugastoridae are separate groups. The key problem is that Strabomantis itself hops around, ha ha, within phylogeny, such that it (and kin) are sometimes outside of a clade that includes Craugastor and kin, and are sometimes within it. Those competing results lead to different taxonomic outcomes (Blackburn & Wake 2011, Pyron & Wiens 2011, Motta et al. 2021).

* Yeah, it’s irritating that both names are in current use, and both have effectively the same meaning. I can see it being useful that one is defined as more inclusive than the other, but I don’t think that anuran workers have done anything like this yet. An additional complication is that some authors have opted to go with the emended spelling Terraranae because this is, apparently, etymologically more correct. The latter point was made by Dubois (2009), and later by Duellman et al. (2016) in their naming of Arboranae, a hyloid clade that includes hylid treefrogs and kin.

Caption: several different topologies have been recovered for Terrarana, though the majority find eleutherodactylids and brachycephalids to be outside a craugastorid + strabomantid clade, with brachycephalids closest. This topology is from the graphical abstract of Heinicke et al. (2018).

The diversity within Strabomantidae has resulted in the naming of four subfamily-level divisions within the group: Strabomantinae, Pristimantinae, Holoadeninae and Hypodactylinae. Which of those is actually worth recognizing in view of the group’s phylogenetic structure obviously depends on which study you consult. Again, this article is not the place for a discussion of that complexity.

And that’s where we’ll end things. As is hopefully clear at this point, the name Strabomantidae is mostly (albeit not universally) applied to a clade of tropical American terraranan or brachycephaloid hyloids that are allied to craugastorids. An alternative view posits that the group’s constituent taxa are better placed within Craugastoridae, in which case a strabomantid clade might still exist but only as a ‘subfamily’. Either way, the lineages concerned are firmly placed within Terrarana/Terraranae/Brachycephaloidea.

It’s also important to note that many frogs relevant to this discussion are endangered or potentially extinct, since they’ve proved hard or even impossible to find since being first named. Degradation and loss of habitat, the impact of fungal infection, and climate change are all connected to strabomantid decline. Also worth noting is that quite a few species do not have agreed-upon conservation status, since data is currently deficient.

Caption: all frogs are great, but hyloids include some of my favourite groups. Clockwise from upper left: the poison-dart frog Phyllobates, the marsupial treefrog Hemiphractus, the white-lipped frog Leptodactylus, and the helmeted water frog Calyptocephalella! Check the links below for articles on most of these animals. Images (clockwise from upper left): Darren Naish; Santiago Ron, CC BY-ND 2.0 (original here); Darren Naish; José Grau de Puerto Montt, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

I like all the anurans, but hyloids are among my favourites and I’ve covered them quite a few times on Tet Zoo before. For previous articles, see…

Green-boned glass frogs, monkey frogs, toothless toads, November 2007

The toads series comes to SciAm: because Africa has toads too, September 2011

20-chromosome toads, September 2011

Glassfrogs: translucent skin, green bones, arm spines, January 2013

Everybody loves glassfrogs, February 2013

African tree toads, smalltongue toads, four-digit toads, red-backed toads: yes, a whole load of obscure African toads, December 2014

Gladiatorial glassfrogs, redux, January 2015

Frogs you may not have heard of: Brazil’s Cycloramphus ‘button frogs’, January 2015

It's the Helmeted water toad… this time, with information!, January 2015

The Terrible Leaf Walker Frog, March 2017

Refs - -

Blackburn, D. C. & Wake, D. B. 2011. Class Amphibia Gray, 1825. In Zhang, Z.-Q. (ed) Animal biodiversity: an outline of higher-level classification and survey of taxonomic richness. Zootaxa 3148, 39-55.

Canedo, C. & Haddad, C. F. B. 2012. Phylogenetic relationships within anuran clade Terrarana, with emphasis on the placement of Brazilian Atlantic rainforest frogs genus Ischnocnema (Anura: Brachycephalidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 65, 610-620.

Dubois, A. 2009. Miscellanea nomenclatorica batrachologica. Class-series nomina are nouns in the nominative plural: Terrarana Hedges, Duellman & Heinicke, 2008 must be emended. Alytes 26, 165-175.

Duellman, W., Marion, A. B. & Hedges, S. B. 2016. Phylogenetics, classification, and biogeography of the treefrogs (Amphibia: Anura: Arboranae). Zootaxa 4104, 1-109.

Frost, D. R., Grant, T., Faivovich, J., Bain, R. H., Haas, A., Haddad, C. F. B., De Sá, R. O., Channing, A., Wilkinson, M., Donnellan, S. C., Raxworthy, C. J., Campbell, J. A., Blotto, B. L., Moler, P., Drewes, R. C., Nussbaum, R. A., Lynch, J. D., Green, D. M. & Wheeler, W. C. 2006. The amphibian tree of life. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 297, 1-370.

Hedges, S. B., Duellman, W. E. & Heinicke, M. P. 2008. New World direct-developing frogs (Anura: Terrarana): molecular phylogeny, classification, biogeography, and conservation. Zootaxa 1737, 1-182.

Heinicke, M. P., Lemmon, A. R., Lemmon, E. M., McGrath, K., & Hedges, S. B. 2018. Phylogenomic support for evolutionary relationships of New World direct-developing frogs (Anura: Terraranae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 118, 145-155.

Jetz, W. & Pyron, R. A. 2018. The interplay of past diversification and evolutionary isolation with present imperilment across the amphibian tree of life. Nature Ecology and Evolution 2, 850-858.

Lynch, J. D. & Ruiz-Carranza, P. M. 1982. A new genus and species of poison-dart frog (Amphibia: Dendrobatidae) from the Andes of northern Colombia. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 95, 557-562.

Motta, A. P., Taucce, P. P. G., Haddad, C. F. B. & Canedo, C. 2021. A new terraranan genus from the Brazilian Atlantic Forest with comments on the systematics of Brachycephaloidea (Amphibia: Anura). Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research 59, 663-679.

Padial, J. M., Grant, T. & Frost, D. R. 2014. Molecular systematics of terraranas (Anura: Brachycephaloidea) with an assessment of the effects of alignment and optimality criteria. Zootaxa 3825, 1-132.