After a gestation that’s involved most of the current century, the long-awaited monographic description of the Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Eotyrannus lengi has finally appeared in print…

Caption: life reconstruction of Eotyrannus lengi by Loana Riboli; copyright, used with permission. Full version shown below.

The study – co-authored by myself and Andrea Cau – is out today in the open-access journal PeerJ. You can go get the paper yourself if you want to, but here’s a personal summary of what it features and the story behind it.

As regular readers might (or should) know, I’ve worked for a couple of decades now on the theropod dinosaurs of the Wealden Supergroup. This is a Lower Cretaceous sedimentary unit, formed of numerous subdivisions, that crops out in south-east England, most famously the Isle of Wight. It yields numerous dinosaurs and other Cretaceous animal groups. Theropods are rare in the Wealden and range from isolated and tantalising fragments all the way to excellent partial skeletons like those of the spinosaurid Baryonyx and the allosauroid Neovenator. Most Wealden dinosaurs are from the unit termed the Wessex Formation.

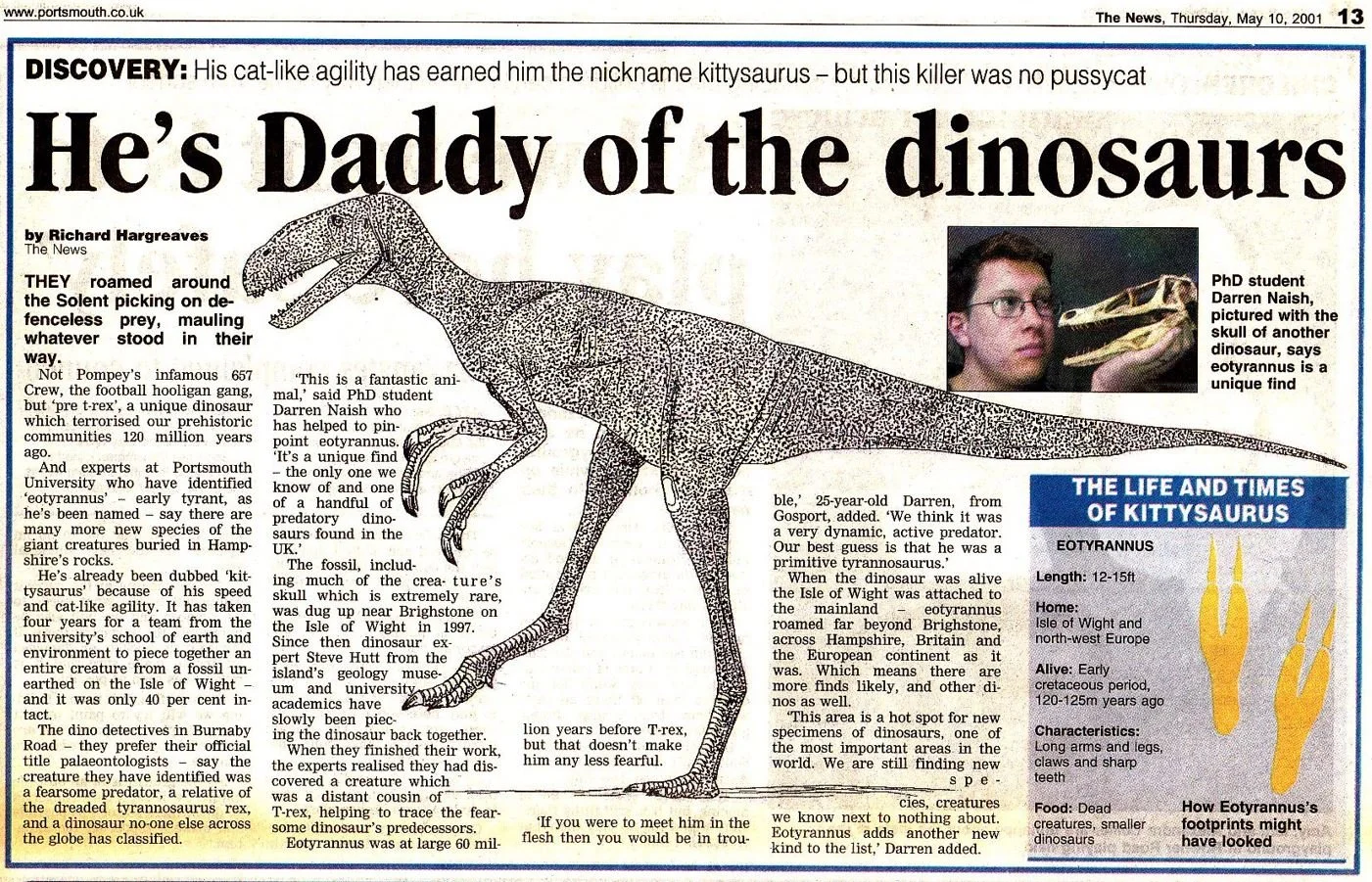

Caption: Eotyrannus goes to the press, round 1. Steve Hutt – theropod expert and Museum of Isle of Wight Geology curator – announced the discovery of Eotyrannus in 1998, and here are various of the somewhat amusing British newspaper pieces that appeared. The UK press is something else.

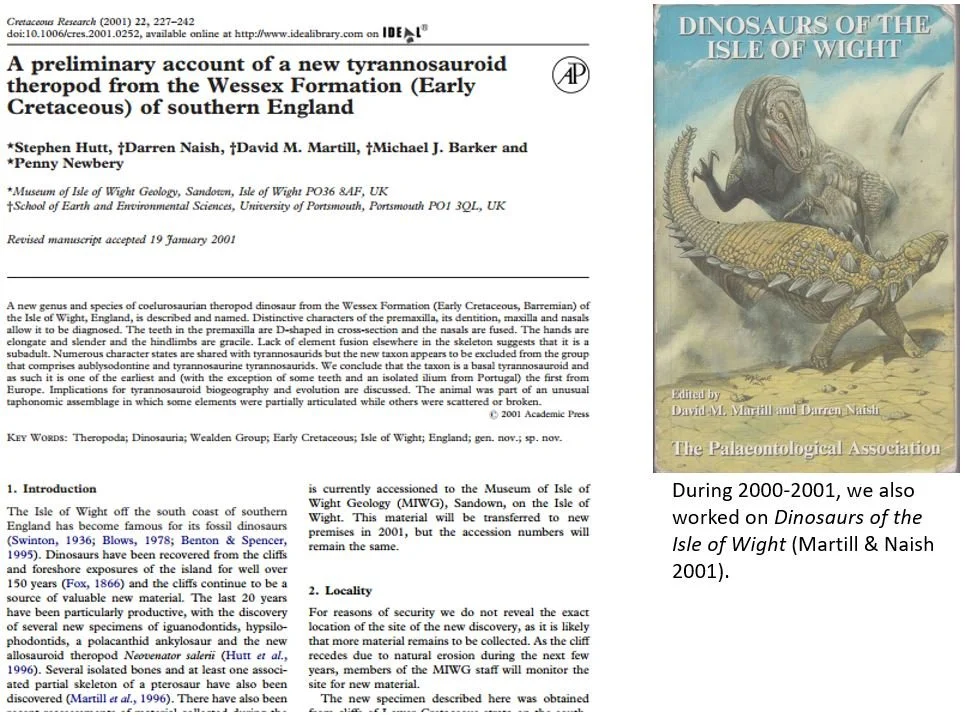

In 1997, a new Wealden theropod specimen was discovered in the Wessex Formation by amateur collector Gavin Leng. It was sensational, and the Museum of Isle of Wight’s then-curator Steve Hutt realised what a big deal it was. It looked tyrannosaur-like. A relationship with the University of Portsmouth’s School of Earth and Environmental Sciences (where I was based as an MPhil student) led to collaboration with the university’s Dave Martill and Mike Barker – both involved in Wealden research at the time – and ultimately to me too. A technical paper was hastily put together, the plan being that it really had to be in the system (if not published outright) prior to the completion of the in-prep book Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight (Martill & Naish 2001) and to the 2001 opening of Dinosaur Isle museum, the replacement for the cramped, tiny former museum. That’s a tall order (and no way to do science), but we managed it. A preliminary paper – Hutt et al. (2001), published in Cretaceous Research – appeared eventually, and the UK’s newest dinosaur – Eotyrannus lengi Hutt et al., 2001 – received its time in the limelight.

Caption: Hutt et al. (2001), Eotyrannus’s birth certificate… which we were working on at the exact same time as we were finishing Martill & Naish (2001), the Palaeontological Association’s Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight.

What I consider to be the main contentions of that 2001 paper have stood up pretty well. Our identification of Eotyrannus as a tyrannosauroid has been supported by all subsequent studies, and our characterisation of it as a ‘mid-sized’ member of the group with proportionally long limbs and a vaguely rectangular snout has stood the test of time as well. So has the idea that Eotyrannus is valid, diagnosable and distinct from the many already named Wealden Supergroup theropods (Hutt et al. 2001).

Caption: Eotyrannus goes to the press, round 2. The publication of the Cretaceous Research paper in 2001 resulted in another lot of coverage. This article – from Portsmouth’s The News newspaper – contains much weirdness, including the nomen nudum Kittysaurus.

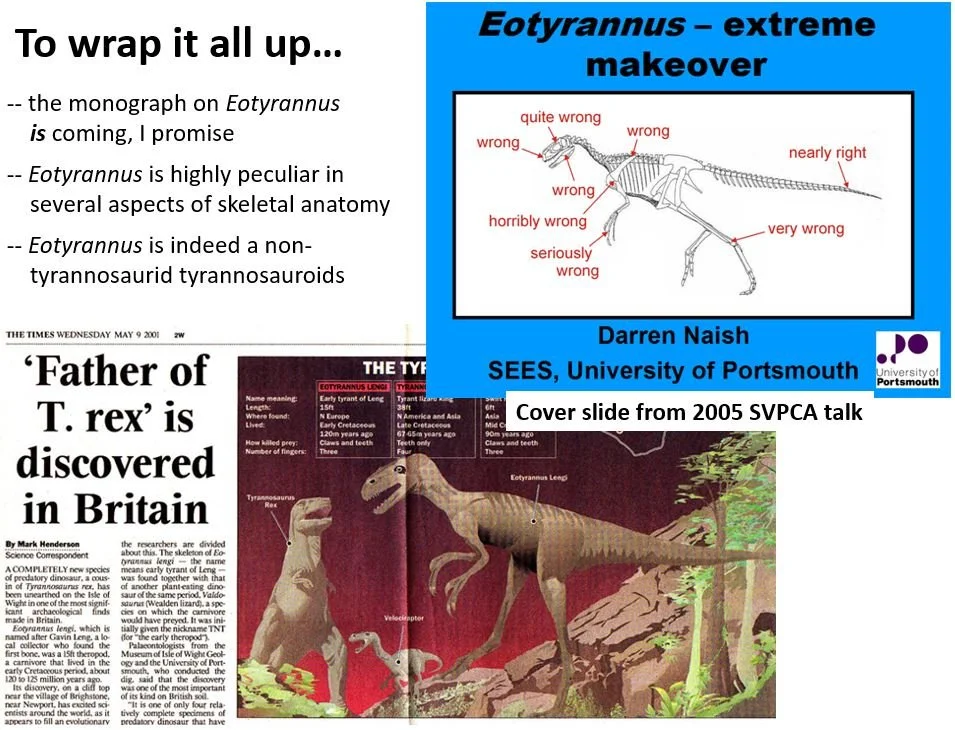

A brief prologue. My descriptive work on Eotyrannus started in the early 2000s when it was agreed that monographing the animal in detail would form the bulk of my PhD at the University of Portsmouth, completed when I was part of Professor Martill’s palaeobiology group. The PhD was completed in 2006. But to publish the thing, I wanted help with the phylogenetics and teamed up with Andrea Cau. The story of what happened next is long and complicated. The first version was submitted in 2012, and years of revision and delay followed. This is mostly down to me: as a freelance researcher who produces and publishes technical research in so-called ‘spare time’ (I’m not a salaried scientist and essentially never have been), I am phenomenally slow when it comes to completing academic works.

Caption: slide I used in an Eotyrannus-themed talk from 2013, which itself features a slide from a talk I gave in 2005, and promises the one-day appearance of the study that’s just appeared (Naish & Cau 2022).

My initial plan for the TetZoo article you’re reading here was to provide a bulletined list of the trials and tribulations the work went through on its way to publication. But I’ve opted not to do that, partly because it’s tedious and niche, partly because it’s under-the-hood stuff you don’t need to hear, and partly because it sounds like whining. All I’ll say for now is that I’ve hated every minute of it, considered giving up on many occasions, and now fully understand why many researchers take decades to complete monographic studies. Work of this sort simply isn’t consistent with life in general, unless you’re specifically employed to do it.

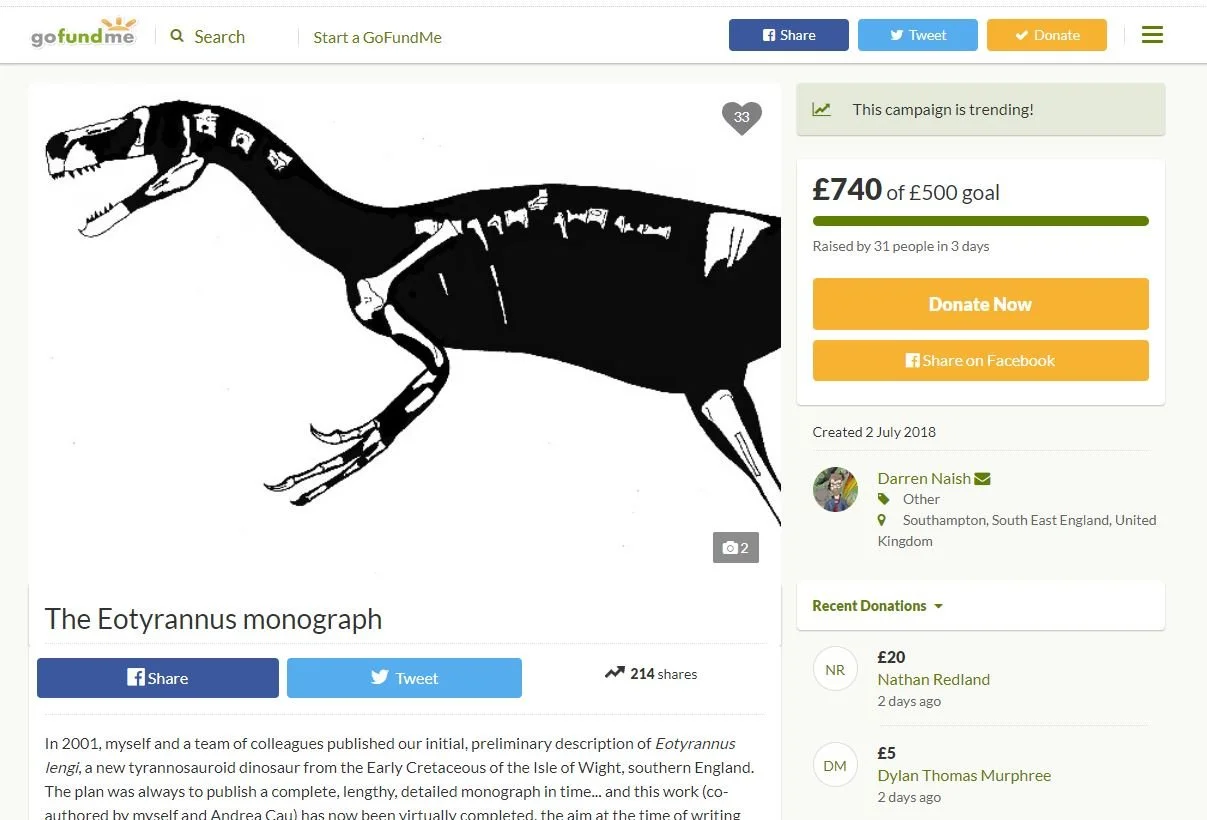

Whatever, I owe a massive debt of thanks to my former mentors, associates, advisors and colleagues at the University of Portsmouth (Dave Martill in particular), to the staff at the former Museum of Isle of Wight Geology and Dinosaur Isle (Steve Hutt, Martin Munt, Alex Peaker and others), and to Andrea for his assistance and co-operation. Finally, the publication of the work required the raising of funds, and I’m pleased to say that a list of friends, colleagues, associates and organisations helped with this, as did my own Patreon supporters. To those who helped: you’re listed in the acknowledgments (Naish & Cau 2022), and I hope I didn’t forget anyone.

Caption: massive heartfelt thanks to everyone who made the publication and Open Access status of this study possible. You’re thanked in the paper. I raised more than I needed; the additional amount has been spent on other academic projects.

Working on Eotyrannus. The Eotyrannus holotype specimen (IWCMS: 1997.550) – a partial skeleton representing an individual about 4.5 m long, recovered at a cliffside exposure of the Wessex Formation – forms part of the collection maintained in the public trust at Dinosaur Isle. This is probably the UK’s largest and most significant collection of dinosaur fossils after that of the Natural History Museum in London, and it’s globally important in terms of Early Cretaceous dinosaurs and other groups.

Caption: Dinosaur Isle Museum at Sandown, Isle of Wight; the repository for the fossils discussed in this article. Photo taken in February 2019. Image: Darren Naish.

Eotyrannus itself is not a pretty fossil. Many of the bones are dark and hard to photograph well, and I haven’t been able to do a good job with the equipment I have. The specimen is part of an extremely hard sideritic concretion that’s difficult to prepare. Substantial preparation has been done on the specimen over the years, but even today there hasn’t been the time or opportunity to do a complete job and we suspect that more information on Eotyrannus awaits recognition inside the concretion. In an ideal world, a large sum of money might be raised to do this work definitively. I wasn’t able to do that, alas, and more work will be done in the future.

Caption: some amount of the Eotyrannus specimen is not pretty. It’s also sometimes difficult to distinguish from the concrete-like matrix, and difficult to interpret. I have hundreds of Eotyrannus photos. Images: Darren Naish.

The main results. Monographs are, by their nature, in-depth and detail-oriented, and for that reason the bulk of the information the monograph (Naish & Cau 2022) contains – concerning the detailed osteology of Eotyrannus – is not all that gee-whiz for people who aren’t involved in technical work on theropod osteology or the diversity, taxonomy and distribution of Wealden dinosaurs. Nevertheless, there are a good number of things here that are of broader interest. Summarised, they’re as follows…

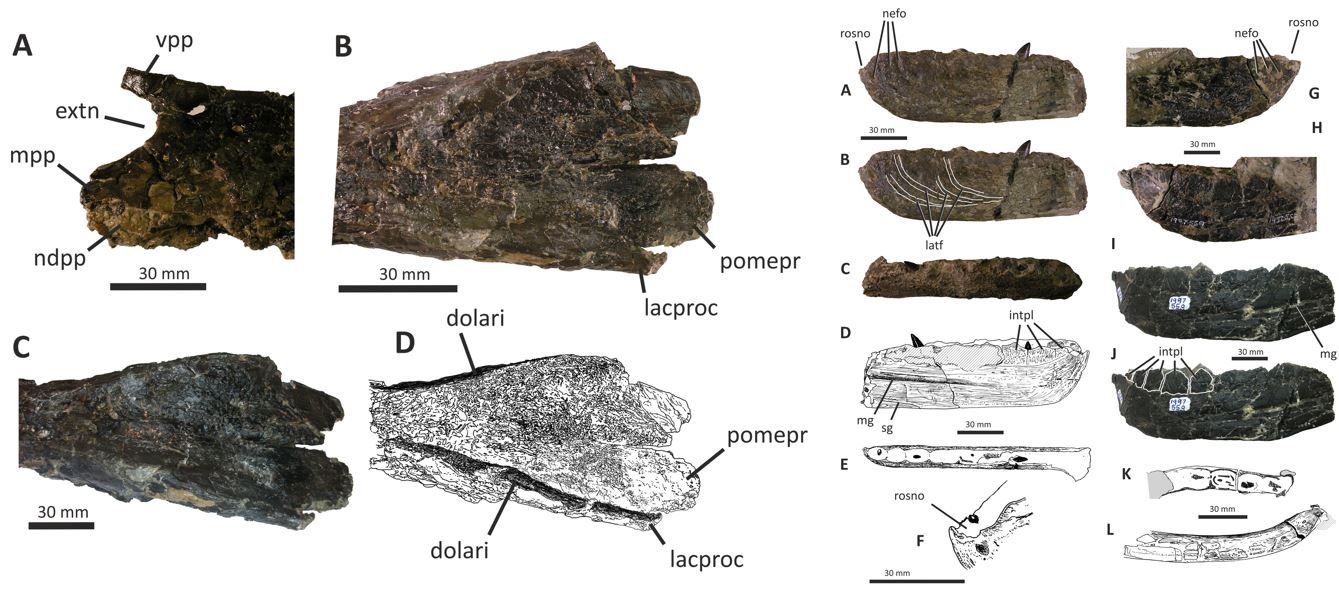

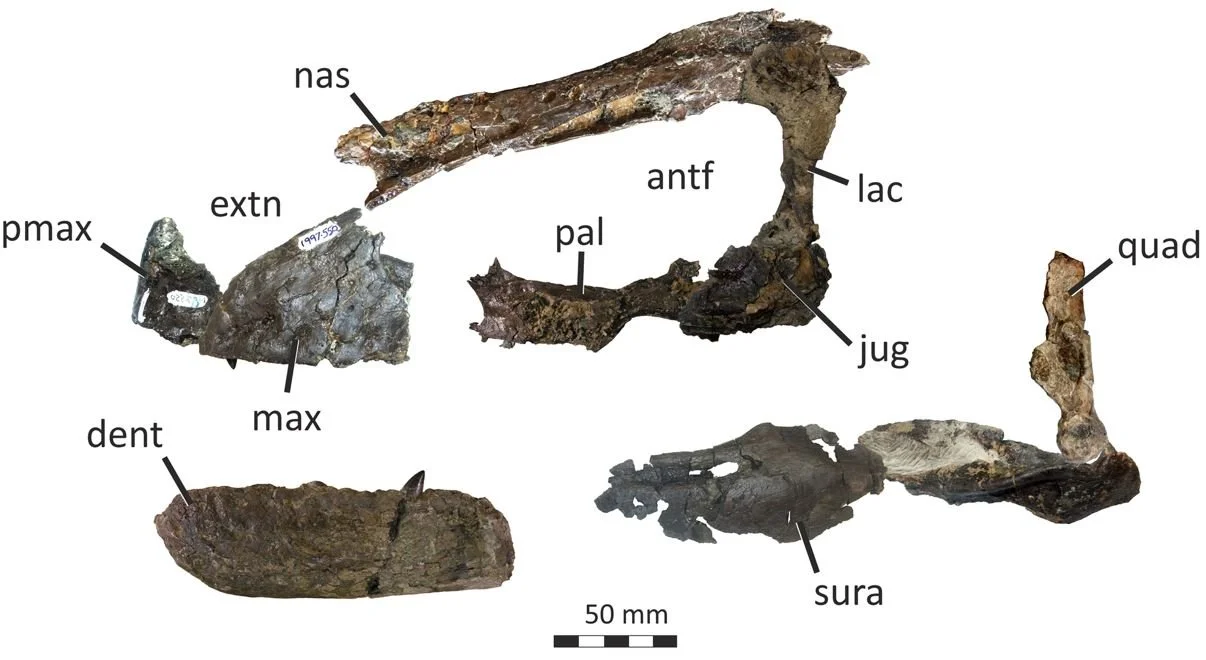

Eotyrannus is a bit more unusual in its proportions, and in certain anatomical details, than realised before. Furthermore, new preparation and analysis has revealed parts of the skeleton that were unknown or unidentified in 2001, including the palatine, part of the jugal, the surangular from the back of the lower jaw, the distal end of the tibia, and more of the ilium (Naish & Cau 2022). The shape of its maxilla show that Eotyrannus wasn’t longirostrine: that is, it didn’t have a long, lightly built snout as did various of its friends and relatives. This might mean that longirostry evolved several times independently in tyrannosauroids (Naish & Cau 2022).

Caption: a few of the many new images included in Naish & Cau (2022), these ones showing (at left) the anterior and posterior ends of the fused nasals, and (at right) the partial dentaries. Images: Naish & Cau (2022).

The fused nasals – one of the key bits of anatomy that first led us to think that we were dealing with a tyrannosauroid (Hutt et al. 2001) – are stranger than originally thought, with massive, triangular recesses on their sides, diverging ridges on the outer margins of the upper surface, and surprisingly large foramina scattered across the convex upper midline (Naish & Cau 2022). There’s a lot going on here and a follow-up study devoted to the nasals alone is in preparation. All I’ll say at this point is that they aren’t simply solid ‘stress conductors’ as implied in the past.

Caption: the known skull bones of Eotyrannus lengi shown in reconstructed life position, excluding isolated teeth and the possible vomer. Broken and missing areas mean that the exact nature of the articulations are unknown. Some elements (like the premaxilla) are reversed from the right side. Image: Naish & Cau (2022).

With respect to the other new bits, recognising a jugal segment is important since it helped establish the height of the skull (the jugal articulates with the lacrimal, which is also known for the animal), and the new data pertaining to the lower jaw was also crucial. A series of curving furrows on the outer surface of the dentary in the lower jaw are unique, and among the most distinctive features of this dinosaur (Naish & Cau 2022). It was also very satisfying to realise that a large ‘mystery bone’ – suggested in my thesis to be the ulna of a different theropod (!) – is actually the distal end of the tibia, meaning that we now have the whole of that bone (Naish & Cau 2022).

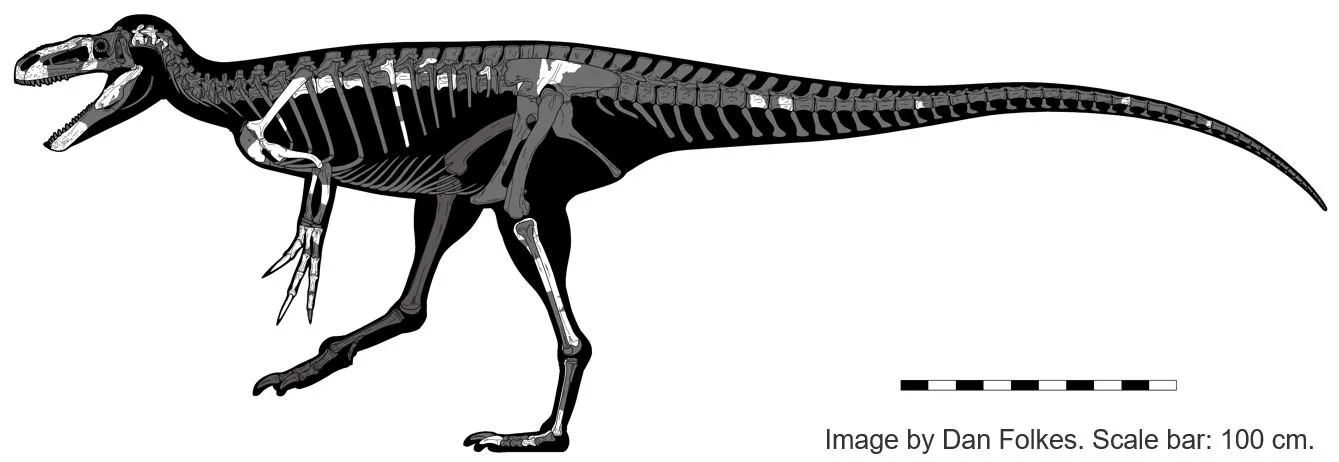

Caption: skeletal reconstruction of Eotyrannus lengi, depicting known elements in reconstructed life position. The positions shown for some of the isolated vertebrae and ribs are conjectural. Scale bar: 100 cm. Image: Naish & Cau (2022)

By combining all this new information, we were able to produce new skull and skeletal reconstructions, including a version constructed by Dan Folkes that extrapolates the appearance of the entire skeleton (Naish & Cau 2022). To my eye, Eotyrannus looks proportionally smaller-headed and thicker-armed that I’d thought before. It remains obvious that a lot of the skeleton is still unknown.

Caption: our new skeletal reconstruction of Eotyrannus lengi IWCMS: 1997.550 depicting the extrapolated appearance of the entire skeleton, with estimated soft tissue outline. The shapes and proportions of those elements unknown from Eotyrannus lengi are based on those of other non-tyrannosaurid tyrannosauroids. Image by Dan Folkes, from Naish & Cau (2022).

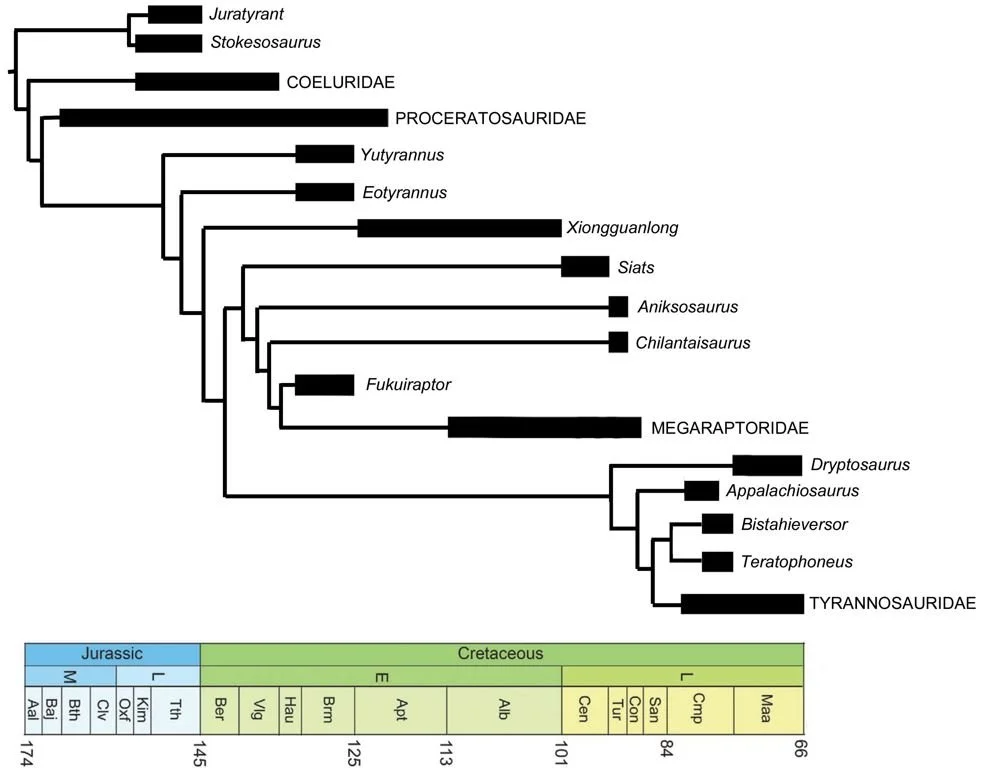

Tyrant phylogeny anew. This new data was also incorporated into a new phylogenetic analysis, and the results are exciting. We didn’t find Eotyrannus to group with the Jurassic taxa Stokesosaurus and Juratyrant, as has been suggested a few times before (Brusatte et al. 2010, Brusatte & Carr 2016, Zanno et al. 2019, Nesbitt et al. 2019), nor is Eotyrannus especially close to Dilong and other early-diverging tyrants (we find Dilong to be a proceratosaurid). Instead, we find Eotyrannus to be part of an ‘intermediate’ grade of mostly gracile, mid-sized tyrannosauroids that lack the key features of tyrannosaurid-like taxa but are more like them than are stokesosaurs, proceratosaurids and Yutyrannus (Naish & Cau 2022).

Caption: time-calibrated tyrannosauroid phylogeny from Naish & Cau (2022). We find stokesosaurs and coelurids to be early-diverging tyrannosauroids, Eotyrannus to be part of an ‘intermediate’ grade closer to tyrannosaurids than Yutyrannus, and megaraptorans to be part of Tyrannosauroidea too.

We also find megaraptorans to be part of this same grade, which is why I’ve been part of Team Tyrannosauroid for megaraptoran affinities for a while now (Naish 2021). This is not a new idea: it was put forward by Novas et al. (2013) and Porfiri et al. (2014), but I think it’s fair to say that it’s been less popular than the idea that megaraptorans are carcharodontosaurian allosauroids (Benson et al. 2010).

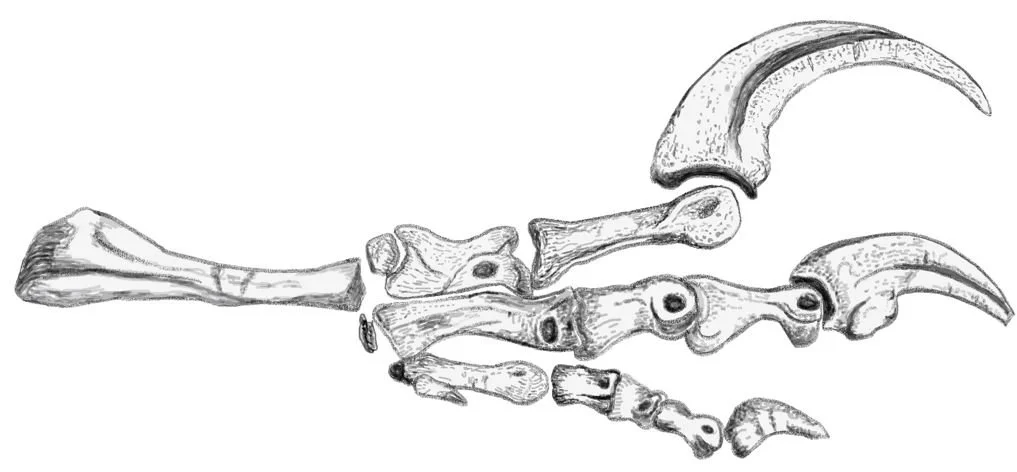

Caption: megaraptorans… it’s been a long, strange trip. This image (from my 2021 Dinopedia) depicts the left forelimb of Megaraptor itself. Image: Darren Naish.

Finding megaraptorans to be part of Tyrannosauroidea is interesting for a list of reasons. It increases the diversity and global significance of tyrannosauroids as a whole, and also means that tyrannosauroids were more important as mid-sized and large predators in North America, Asia, South America and Australia during the Early and ‘middle’ Cretaceous than generally thought (Naish & Cau 2022). It also suggests that a tyrannosauroid lineage (Megaraptora) was partly ‘responsible’ for slowing the diversification of the lineage that includes tyrannosaurids. A similar proposal was made by Zanno & Makovicky (2013), except they posited megaraptorans as allosauroids. Interpreting megaraptorans as tyrannosauroids makes the Cretaceous more ‘coelurosaur-dominated’ than it is where the relevant taxa are interpreted as allosauroids. Allosauroids are still there, just less diverse. Finally on megaraptorans, I want to reiterate that Eotyrannus itself is not part of this clade – as suggested by Porfiri et al. (2014) – and doesn’t possess the characters it was said to have in the study concerned.

Caption: life reconstruction of Eotyrannus lengi by Loana Riboli; copyright, and used with permission.

Team Wealden. Our study includes some reasonable discussion of how Eotyrannus compares to other Wealden theropods (Naish & Cau 2022). As I’ve said a few times (probably more in talks and popular articles than technical papers), an early expectation that Eotyrannus might prove synonymous with one (or more) of the named Wealden theropods proved unsupported. It’s different from all of them, which is good for Eotyrannus but not for those other taxa, since they still remain mostly enigmatic and known only from fragments (I’ll avoid discussing the Angeac material for now).

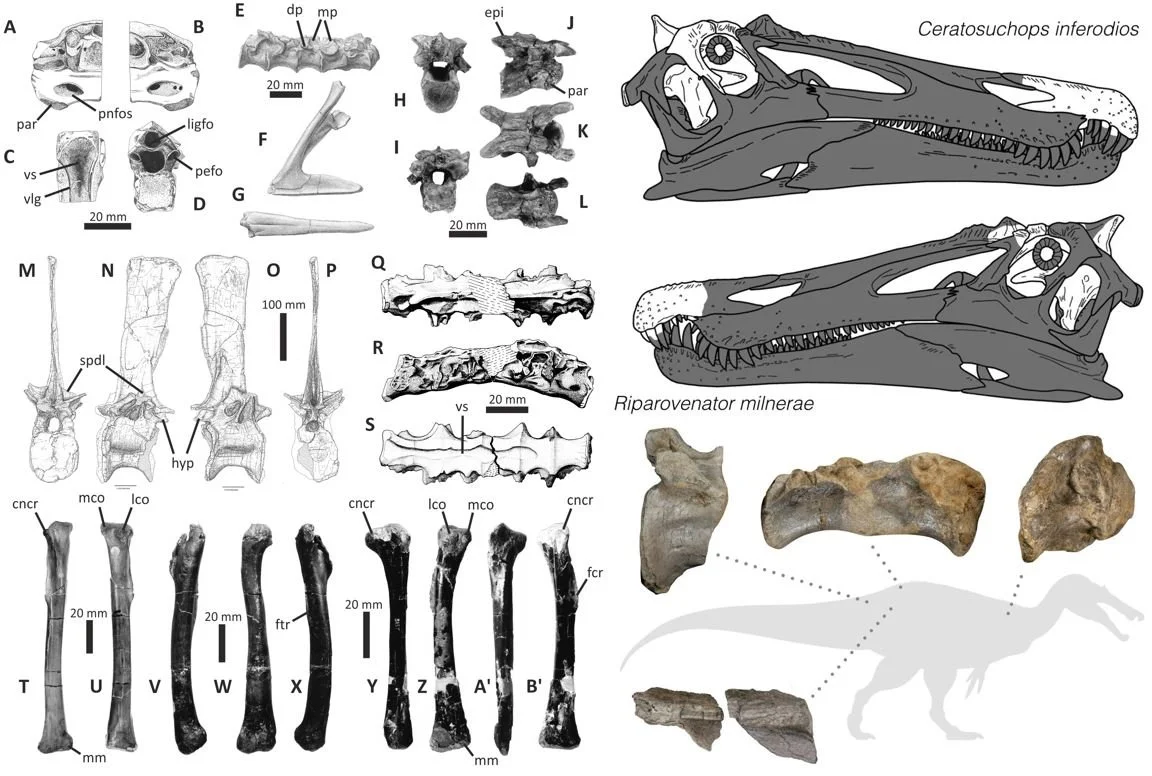

Caption: other Wealden theropods, some more relevant to Eotyrannus than others. At left is a montage of assorted Wessex Formation remains - as figured in Naish & Cau (2022) - and at right we see (at upper right) the reconstructed skulls of the two Wessex Formation baryonychines published in 2021 (Images by Dan Folkes, from Barker et al. (2021)) and (at lower right) elements of the White Rock spinosaurid and where we think they come from (silhouette by Dan Folkes).

The world of dinosaur science moves quickly, and various additional Wealden theropod studies appeared while the Eotyrannus monograph was in press. It was submitted some considerable time before the recent work on Wealden spinosaurids (Barker et al. 2021, 2022) was published, and as a consequence it’s out of date in its discussion of baryonychine taxonomy and distribution, instead following the taxonomy I suggested in Naish (2011). The new Wessex Formation dromaeosaurid Vectiraptor (Longrich et al. 2021) also fails to get mention, which is unfortunate but not much of a big deal since the peculiar vertebral features of Vectiraptor aren’t relevant to Eotyrannus anyway.

While there are more Wealden theropod studies to come (a fair amount of work is in preparation at the time of writing), seeing the known osteology of Eotyrannus properly described at last should be helpful. One thing I hope for is the realisation that various isolated or fragmentary remains already in collections might now be recognised as additional specimens, in which case they really should be put on record.

Caption: research on Eotyrannus started here. Or, more specifically, upstairs: what used to be the Museum of Isle of Wight Geology, Sandown, above Sandown Public Library. Photo taken in February 2019. Image: Darren Naish.

And that’s it for now. I cannot over-emphasise what a significant personal accomplishment the appearance of this work is. It’s certainly not perfect, and there’s more work to do, as is always the case in science. But getting it out and citeable is the battle I was fighting here.

My co-author Andrea has also blogged about the new paper: his article is here.

For previous TetZoo articles on Wealden theropods and associated issues (some links here are to wayback machine versions due to destruction or paywalling of everything at versions 2 and 3), see…

Of Becklespinax and Valdoraptor, October 2007

The world’s most amazing sauropod, November 2007

Oh no, not another new Wealden theropod!, June 2009

Concavenator: an incredible allosauroid with a weird sail (or hump)... and proto-feathers?, September 2010

The Wealden Bible: English Wealden Fossils, 2011, November 2011

Ostrich dinosaurs invade Europe! Or do they?, June 2014 (every archived version of this article lacks the original illustrations, sorry)

Theropod Dinosaurs of the English Wealden, Some Questions (Part 1), March 2020

Introducing ‘Unexpected Isle of Wight Air-Filled Hunter’, a New English Theropod Dinosaur, September 2020

Dr Angela Milner and the Discovery of Baryonyx, August 2021

Two New Spinosaurid Dinosaurs from the English Cretaceous, September 2021

A Giant Spinosaurid Dinosaur from the Cretaceous of the Isle of Wight, June 2022

Refs - -

Benson, R. B. J., Carrano, M. T. & Brusatte, S. L. 2010. A new clade of archaic large-bodied predatory dinosaurs (Theropoda: Allosauroidea) that survived to the latest Mesozoic. Naturwissenschaften 97, 71-78.

Brusatte, S. L., Norell, M. A., Carr, T. D., Erickson, G. M., Hutchinson, J. R., Balanoff, A. M., Bever, G. S., Choiniere, J. N., Makovicky, P. J. & Xu, X. 2010. Tyrannosaur paleobiology: new research on ancient exemplar organisms. Science 329:1481-1485.

Longrich, N. R., Martill, D. M. & Jacobs, M. L. 2021. A new dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Barremian) of the Isle of Wight, and implications for European palaeobiogeography. Cretaceous Research 105123.

Naish, D. 2011. Theropod dinosaurs. In Batten, D. J. (ed.) English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 526-559.

Nesbitt, S. J., Denton, R. K., Loewen, M. A., Brusatte, S. L., Smith, N. D., Turner A. H., Kirkland, J. I., McDonald, A. T. & Wolfe, D. G. 2019. A mid-Cretaceous tyrannosauroid and the origin of North American end-Cretaceous dinosaur assemblages. Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (6), 892-899.

Novas, F. A., Agnolín, F. L., Ezcurra, M. D., Porfiri, J. & Canale, J. I. 2013. Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: the evidence from Patagonia. Cretaceous Research 45:174-215.

Porfiri, J. D, Novas, F. E., Calvo, J. O., Agnolín, F. L., Ezcurra, M. D. & Cerda, I. A. 2014. Juvenile specimen of Megaraptor (Dinosauria, Theropoda) sheds light about tyrannosauroid radiation. Cretaceous Research 51, 35-55.