Have we discovered one of vertebrate palaeontology’s most famous ‘missing’ specimens? Well, read on…

If you’ve ever looked at a book or article that discusses the early history of dinosaur discoveries, chances are high that you’ve read about a large partial bone documented in 1677 by Dr Robert Plot (1640-1696) in his The Natural History of Oxford-shire. Plot – a naturalist, antiquarian and scientist – was both Professor of ‘Chymistry’ at Oxford University and first Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. In fact, he was the only person to ever hold both positions at the same time. He apparently did this as neither one paid well enough to provide a living wage… insert here appropriate quip about scientific and museum salaries.

Caption: at left, the best known portrait of Robert Plot of Oxford, naturalist, antiquarian and scientist. At right, his famed book of 1677.

It was in his aforementioned book that Plot chronicled various geological oddities discovered in the Oxfordshire countryside. Plot’s views on the origins and identities of these objects have to be seen within the context of the time: fossils and fossilisation were not understood, and it was suspected that objects dug from the earth were formed naturally by some sort of generative process, a “plastic virtue, latent in the earth” (Plot 1677, p. 112).

Our focus here is on a large, incomplete bone that Plot discussed and illustrated, given to him by “the ingenious Sir Thomas Pennyston”. It had been discovered in a quarry in the parish of Cornwell, Oxfordshire (not to be confused with Cornwall in England’s south-west). The specimen’s exact geological provenance isn’t known but it’s thought that it came from the Middle Jurassic (Bajocian or Bathonian) oolitic limestone of the region (Delair & Sarjeant 2002). Plot recognised – correctly – that the specimen looked like the distal end of a femur, or thigh bone, and wrote that it “has exactly the figure of the lowermost part of the thigh-bone of a man, or at least of some other animal” (Plot 1677, p. 132) before describing its detailed anatomy.

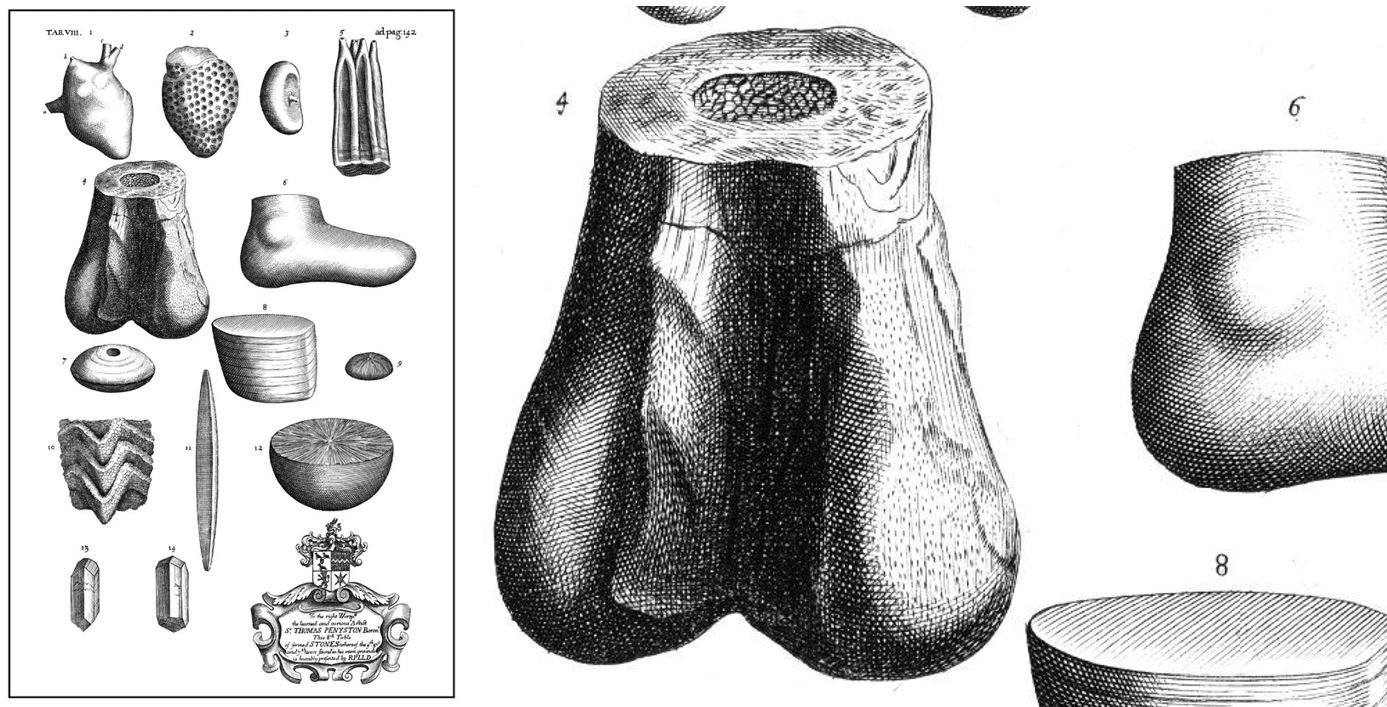

Caption: at left, the relevant plate from Plot’s 1677 book The Natural History of Oxford-shire. The famed specimen is shown alongside objects discovered in the ground, and thought to represent a petrified heart and human foot, as well as assorted rhomboidal and trapezoidal objects.

Because the bone was larger than that of a horse or ox, Plot wondered if it might have come from an elephant “brought hither during the Government of the Romans in Britain” (Plot 1677, p. 133), but noted that “this opinion too lies under so great difficulties, that it can hardly be admitted”. He was in fact sufficiently sceptical that he wanted to see this idea tested. Remarkably, he managed to examine actual elephant bones in 1676 and found them very different in shape and size from the Cornwell bone.

Plot was left with no option but to conclude that the bone was from a giant person, and he devoted a few pages of his text to chronicling those giant men and women discussed in antiquarian sources (Plot 1677, pp. 136-138). It’s impossible today to appreciate how Plot and other people of his time might have regarded the discovery of physical evidence for the existence of giant humans, some of whom were considered by Plot to be 17 ft tall (Plot 1677, p. 137). It requires a worldview we just can’t appreciate.

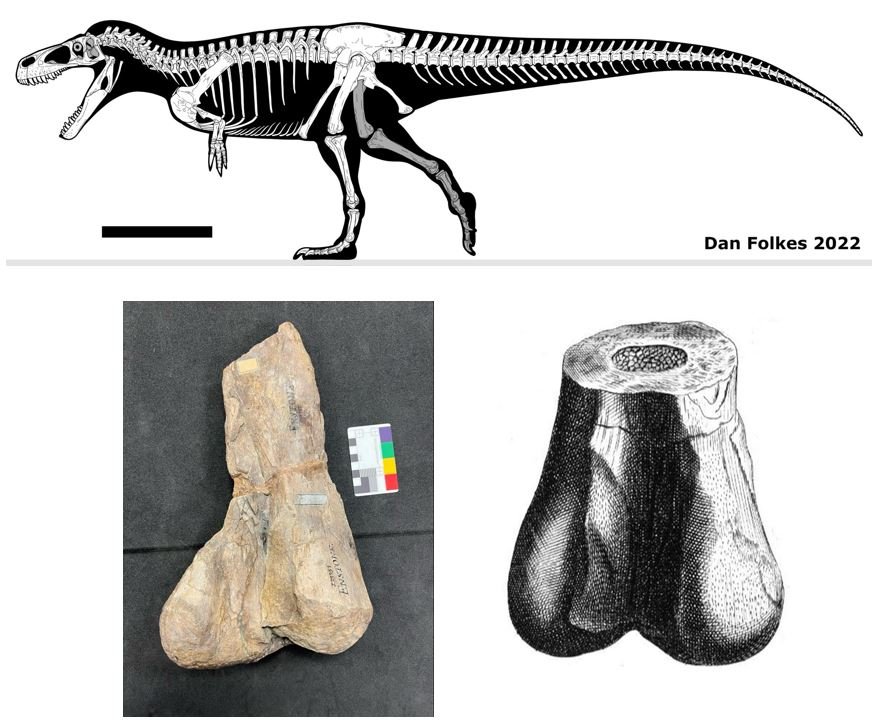

Caption: it’s been generally agreed for decades now that the Plot bone likely belonged to Megalosaurus, the large tetanuran theropod famously associated with the Middle Jurassic sediments of Oxfordshire. Whether this is justifiable is a complex issue, but I’ve essentially followed that assumption here. Megalosaurus skeletal reconstruction by Dan Folkes, used with permission.

Brookes and ‘Scrotum Humanum’. The Cornwell bone was written about again by Richard Brookes in his 1763 book The Natural History of Waters, Earths, Stones, Fossils, and Minerals, with their Virtues, Properties, and Medicinal Uses, to which is added the Methods by which Linnaeus has treated these subjects, Vol. 5 of A New and Accurate System of Natural History (Brookes 1763). Brookes’s writings and illustrations of fossils and supposed fossils were very similar to those of Plot and evidently based on them. He depicted the Cornwell bone again, albeit in more schematic fashion and inverted relative to the figure provided by Plot.

Brookes’s (1763) text makes it clear that, like Plot, he regarded the specimen as “the lowermost part of the thigh-bone of a man” (Brookes 1763, p. 317) but his plate (published opposite p. 318 of his book) labels it not as the lower-most part of a thigh bone, but as ‘Scrotum Humanum’. Why the book’s text and plate provide different, competing identifications isn’t obvious, but they do.

Caption: plate from Brookes (1763) showing the bone and other objects. It’s obvious that several of the objects illustrated here were redrawn directly from Plot’s plate of 1677. Note that the label ‘Scrotum Humanum’ is written in the same style as such obvious labels as ‘Kidney Stone’ and ‘Petrifaction’.

And here’s the origin of the idea that the object was misidentified as the scrotum of a giant human, and that the bone was awarded the scientific name Scrotum humanum (Halstead 1970, Delair & Sarjeant 1975, Norman 1992, Torrens 1995, Spalding & Sarjeant 2012).

At least a few writers after Brookes took this idea seriously, the French philosopher Jean-Baptiste Robinet going so far as to claim – in 1768 – that the specimen preserved visible traces of musculature and even a urethra (Buffetaut 1979). The late palaeontologist Beverley Halstead argued – apparently seriously – that Scrotum humanum should stand as the first technical name ever attached to a (non-bird) dinosaur, and that it should be considered technically admissible seeing as its publication post-dated the 1758 appearance of the 10th edition of Carl Linnaeus’s Systema Naturae (Halstead 1970), the work responsible for establishment of the binomial system. Halstead died in 1993 but his colleague William Sarjeant (who himself died in 2002) apparently tried petitioning the ICZN (International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature) to have the ‘name’ technically supressed so that it wouldn’t usurp those names it might be considered synonymous with, namely Megalosaurus bucklandii (Halstead & Sarjeant 1993). Spalding & Sarjeant (2012) noted that this “proposition has now been firmly rejected by the cognoscenti of zoological taxonomy” (p. 10).

Caption: the Megalosaurus display at Oxford University Museum of Natural History (photographed in 2016), showing most of the original bones as described by Buckland in 1824. Note that an illustration of the Plot bone occupies the centre. Image: Darren Naish.

This whole saga always was a silly waste of time and I don’t think Halstead was being serious in the first place. ‘Scrotum Humanum’ is transparently a label on the relevant plate, not an attempt to attach a scientific name to a species. It’s written alongside such other labels as ‘Kidney Stone’ and ‘Petrifaction’.

Where is the Plot bone today? That, then, is the required preamble on the specimen, which I’ll call ‘the Plot bone’ from hereon (the term ‘Cornwell bone’ has been used here and there too). Whatever became of the Plot bone? Where is it today? A certain cartoon notwithstanding (see below), popular history has it that the specimen is lost: that we simply have no idea, today, what happened to it or where it might be.

Caption: an illustration reproduced by Torrens (1995) wherein the caption reads “Little girl and Scrotum humanum, from the title page of Dinosaur Bones by ‘Aliki’, London : A. & C. Black, 1989”.

Over recent years I’ve worked closely (due to my role as scientific consultant for the BBC Studios/Apple TV+ series Prehistoric Planet) with Paul Stewart. Paul is a qualified zoologist (his PhD was on the behaviour of European badgers Meles meles, completed under Professor David Macdonald at the University of Oxford) and has a serious interest in palaeontological history, especially in early ideas about dinosaurs, marine reptiles and Pleistocene mammals.

Caption: Dr Paul Stewart and a taxiderm specimen of a European badger at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Image: Darren Naish.

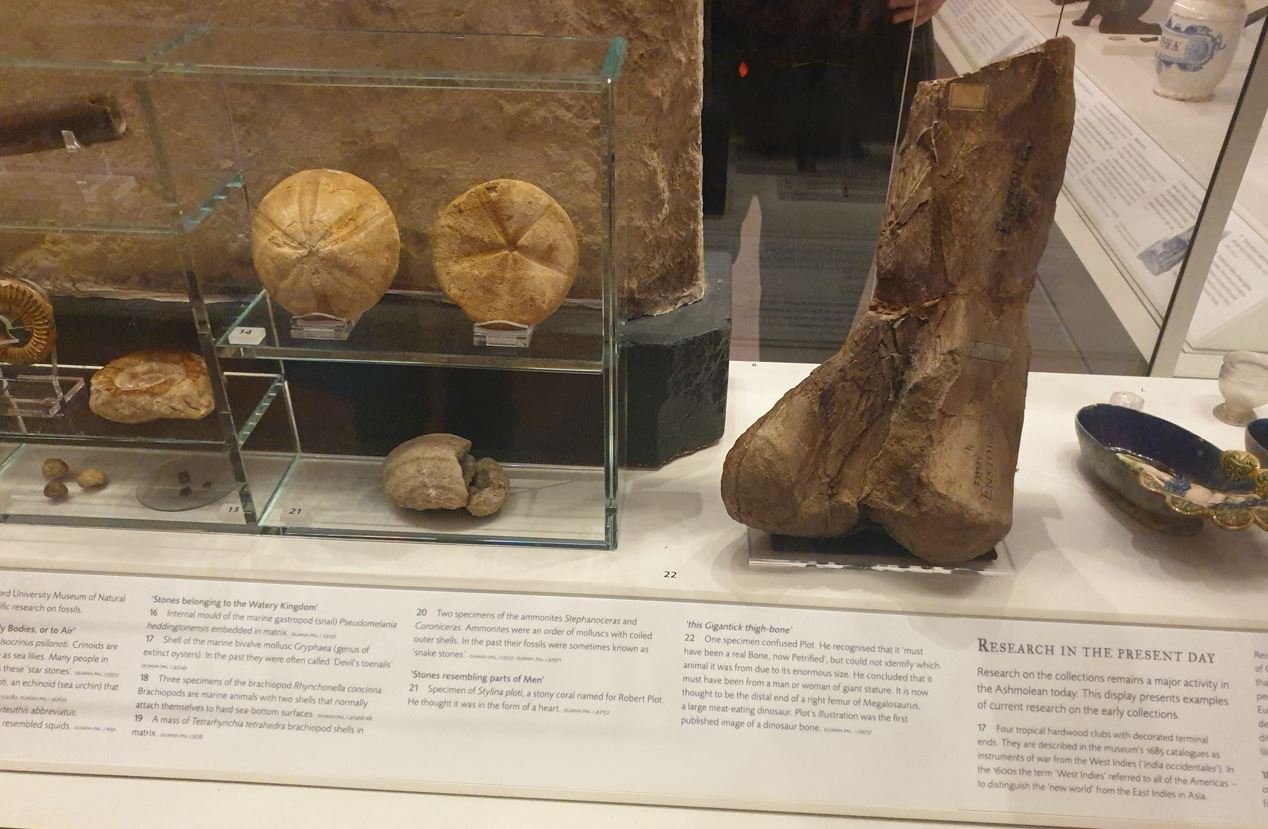

The Plot bone found, perhaps. While working with Paul one day, he dropped a bit of a bombshell. He’d noticed that what appeared to be the Plot bone was very much still in existence, and – furthermore – was on show in a museum; specifically, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. The Ashmolean is devoted to art and archaeology so it’s conceivable, I suppose, that a specimen as famous as the Plot bone might be on show there but not noticed by the staff (few of which are experts on fossils) nor by visitors. The specimen concerned did not belong to the Ashmolean but to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, where it’s accessioned as OUMNH PAL J29757. For ease of reading, I’ll call it the ‘Ashmolean bone’ from hereon.

Caption: OUMNH PAL J29757, as on display at the Ashmolean Museum in February 2020. At left, the specimen in posterior view. At right, anterior view. Images: Darren Naish.

The Ashmolean bone is obviously the distal end of a dinosaur femur, its prominent condyles and other structures showing that it belongs to a tetanuran theropod dinosaur, and perhaps to Megalosaurus or a close relative. Cracks and areas of damage much resemble features visible in Plot’s original illustration but it was obviously different from the Plot bone in that the hollow interior wasn’t visible. We reasoned that a section of shaft had been glued on to the distal, condyle-bearing end: a crack separating the two was in exactly the right position to make the distal end look like the Plot bone if imagined on its own, and the label on the shaft section suggested a history distinct from that of the distal end. Maybe, we surmised, they’d been discovered at different times and only connected sometime after Plot and Brookes had written about the specimen.

Also relevant is that Plot’s illustration of the specimen was a mirror-image of the real thing, meaning that direct comparison between it and the Ashmolean bone made them look quite different. If we flip Plot’s illustration back to how it ‘should’ look, we see some points of similarity between it and the Ashmolean bone.

Caption: a reasonable list of detailed similarities exist between the Ashmolean bone (at left) and the Plot bone (here, flipped back to its original orientation), enough that we became quite confident that the two might be the same thing. If my interpretation of anatomical features is correct, both illustrations here depict the distal end of a right femur.

Antique labelling reveal that the Ashmolean bone originated at Enstone, which is encouraging because this is the former location of a quarry within the parish of Cornwell (which, you’ll recall, is where the Plot bone came from).

Paul seemed moderately confident, but I wanted another opinion and so put all of this to Martin Simpson. Martin and I have worked together on Cretaceous pterosaurs and dinosaurs and he’s especially interested in historical palaeontology, owning a substantial amount of relevant material (original publications and so on) himself. By comparing the various cracks, areas of damage and detailed anatomical nuances of the Ashmolean bone with illustrations of the Plot bone, Martin also became confident that the two were indeed a good match. Between the three of us, we began working on a plan to write this up as a technical paper. If we were right, this was a pretty big deal: one of vertebrate palaeontology’s most famous, or infamous, early specimens wasn’t lost, but had been successful relocated.

Caption: OUMNH PAL J29757 within the Robert Plot display at the Ashmolean Museum in February 2020. Plot also obtained and wrote about crinoids, bivalves, brachiopods, ammonites and corals. The fossil coral immediately to the left of the theropod femur belongs to a sort suggested by Plot to be identifiable as petrified human hearts. Images: Darren Naish.

Paul, Martin and I met up at the Ashmolean early in 2020 and examined the bone as best as we could. It was (and currently still is) part of a display devoted to the museum’s early history and Plot’s role specifically. It ‘stands in’ for the Plot bone and there’s no clear indication from the labelling that that’s not what it is.

Caption: part of the Plot display at the Ashmolean Museum (in February 2020), with three of the primary investigators staring at it in loving fashion. Darren Naish at far left; Martin Simpson standing at right; Paul Stewart at lower right.

Hands-on with the Ashmolean bone. What tests might be possible in order that our suggested identification could be checked? Our knowledge of the Plot bone doesn’t just concern its external appearance: we also know something about its size. Plot (1677) wrote that it was about 15 inches in circumference around the shaft, about 24 inches in circumference around the bulbous distal end, and about 20 lbs in weight. Plot (1677) also provided details on its interior, since its hollow shaft was filled at its bottom with a sparry mineral, supposed by Plot to perhaps be petrified marrow. In order to check these things, we’d need to examine the specimen outside of a display case, and measure and weigh it appropriately.

We approached Hilary Ketchum, Collections Manager at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History. Hilary might not work at the Ashmolean, but her contacts in the Oxford museum world would be essential and she’d know how best to get access to the specimen in person. And she proved so important that we wanted her as part of the team.

Getting access to museum specimens that are on display can be complicated and slow, since it takes a while for the right people to be available at the right time. The Ashmolean is also an exceptionally busy museum, and we were requesting special access to a specimen right at the height of the covid pandemic. We got the ball rolling in February 2020, but any and all plans were thwarted as the museum effectively became closed to research visits for the rest of the year. Thanks to organisation work from Hilary and co-operation from collections staff at the Ashmolean, we finally got the required access to the specimen in December 2021.

Caption: OUMNH PAL J29757 on the day of reckoning, the images again emphasising how compressed it is at its preserved proximal end. Images: Paul Stewart.

Denouement. On the day of reckoning, Paul and Hilary met at the Ashmolean to examine, weigh and measure the bone in person. It proved to be a pretty good match for Plot’s bone in rough dimensions. But here’s where things essentially fell apart. The Ashmolean bone is a veritable lightweight relative to the Plot bone, weighing about half of what it ‘should’.

Could there still be an interior hollow filled with a sparry mineral ‘marrow’, as Plot had described in 1677? Well, maybe, but there would be no point in breaking the Ashmolean bone open to find out in view of the very different measurements already evident. The conclusion had to be that the specimen was not the Plot bone after all. And at this point our hope that we might have discovered the original Plot bone were dashed. We hadn’t. It remains of unknown whereabouts.

Caption: OUMNH PAL J29757 again on the day of reckoning, this time with Hilary’s hands providing useful indications of scale. From left to right, we see the specimen in posterior view, medial view, and proximal view. The size means that this can’t be the Plot bone after all. Images: Paul Stewart.

Most scientific stories that involve the suspected discovery of a given thing – whether it’s a new animal species, a fossil or a biological phenomenon or event – end with the thing being found: with positive results. But a major part of the scientific process involves negative results; we often fail to find or confirm what we hoped we would, an outcome that feels like failure.

However, scientific results are results however they pan out, and failing to confirm something, or confirming that something is not the thing you hoped or suspected it was, is still important. For that reason, we can feel good about the fact that we investigated a specimen and found that it was not the one we hoped it would be, even though that doesn’t result in the high-profile publication and undoubted fame and fortune we were aiming for. I kid, of course. But here ends our story.

Caption: the Plot bone - a mainstay of popular and academic books on dinosaurs - remains lost after all. This montage shows just a few of the many appearances the bone has enjoyed in the literature.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on historical palaeontology, see…

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

Up Close and Personal With the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, December 2018

Refs - -

Brookes, R. 1763. The Natural History of Waters, Earths, Stones, Fossils, and Minerals, With Their Virtues, Properties and Medicinal Uses, To Which Is Added, the Method in Which Linnaeus Has Treated These Subjects, Vol. 5 of A New and Accurate System of Natural History. Newbery, London.

Buffetaut, E. 1979. A propos du reste de dinosaurien le plus anciennement décrit: l’interprétation de J. B. Robinet (1768). Histoire et Nature 14, 79-84.

Delair, J. B. & Sarjeant, W. A. S. 1975. The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs. Isis 66, 5-25.

Delair, J. B. & Sarjeant, W. A. S. 2002. The earliest discoveries of dinosaurs: the records re-examined. Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association 113, 185-197.

Halstead, L. B. 1970. Scrotum humanum Brookes 1763 – the first named dinosaur. Journal of Insignificant Research 5, 14-15.

Halstead, L. B. & Sarjeant, W. A. S. 1993. Scrotum humanum Brookes – the earliest name for a dinosaur. Modern Geology 18, 221-224.

Norman, D. B. 1992. Dinosaurs past and present. Journal of Zoology 228, 173-181.

Plot, R. 1677. The Natural History of Oxfordshire, being an Essay toward the Natural History of England. Robert Plot, Oxford.

Spalding, D. A. E. & Sarjeant, W. A. S. 2012. Dinosaurs: the earliest discoveries. In Brett-Surman, M. K., Holtz, T. R. & Farlow, J. O. (eds) The Complete Dinosaur (Second Edition). Indiana University Press (Bloomington & Indianapolis), pp. 3-23.

Torrens, H. S. 1995. The dinosaurs and dinomania over 150 years. In Sarjeant, W. A. S. (ed) Vertebrate Fossils and the Evolution of Scientific Concepts. Gordon and Breach Publishers, pp. 255-284.