Yup, another new dinosaur from the Cretaceous of the UK…

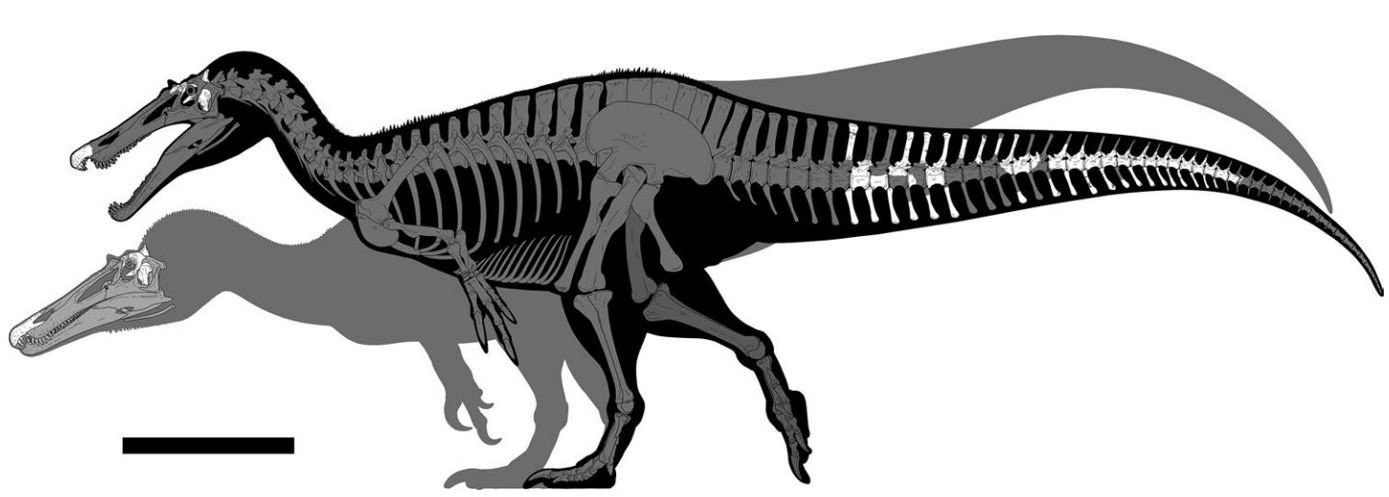

Caption: speculative reconstruction of our new animal, the White Rock spinosaurid. For full version, see below. Image by Anthony Hutchings.

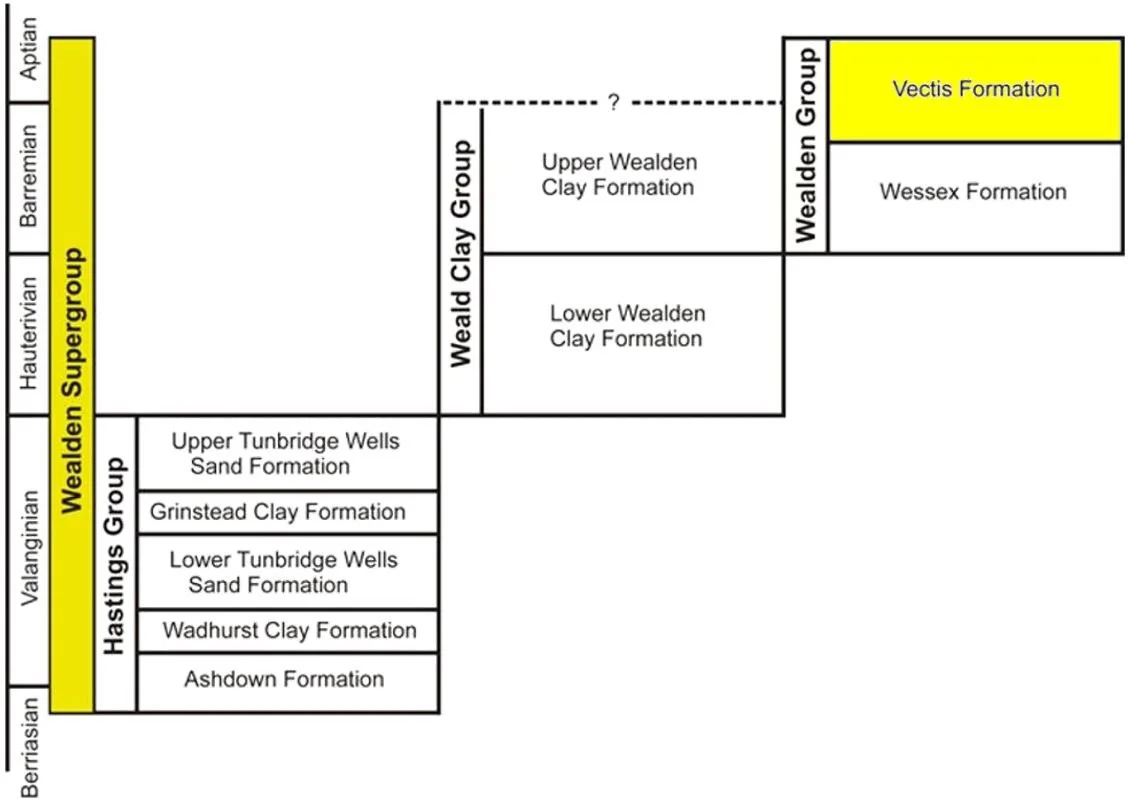

Regular readers of TetZoo will know that I often write about the dinosaurs and other fossil reptiles of the Wealden Supergroup. What’s the Wealden Supergroup? It’s a complex succession of Lower Cretaceous sediments that crops out in the south-east of England – most famously on the south-west and south-east shores of the Isle of Wight – and which preserves diverse environments and numerous fossils. New Wealden dinosaurs are reported on a regular basis (four new species were published last year alone), and we’re here right now because today sees the publication of yet another one…

Caption: last year – right after we’d published the baryonychine paper (Barker et al. 2021) – I teased the existence of additional Isle of Wight spinosaurid remains via the release of this image, but with the bones on the table blacked out. Here’s an uncensored version :) The replica skull at the back was borrowed courtesy of Dinosaur Isle Museum.

Last year, Phd student Chris Barker, Dr Jeremy Lockwood, Dr Neil Gostling, myself and a team of colleagues published two new spinosaurid dinosaur species from the Isle of Wight Wealden (Barker et al. 2021). These are Riparovenator milnerae (known from a partial skull and associated tail) and Ceratosuchops inferodias (known only from a partial skull).

Despite looking superficially similar to Baryonyx walkeri – a Wealden spinosaurid from the English mainland, published in 1986 and effectively a ‘Rosetta Stone’ in terms of shaping our understanding of spinosaurids (Charig & Milner 1986, 1997) – both proved more similar to Suchomimus from Africa and group with it in phylogenetic studies (Barker et al. 2021). Not only do Riparovenator and Ceratosuchops increase the number of spinosaurid taxa known from the Wealden and western Europe as a whole, they also provide support for the idea that spinosaurids originated in this region before giving rise to lineages that spread south and east (Barker et al. 2021).

Caption: known skeletal elements of Ceratosuchops (grey silhouette) and Riparovenator (black silhouette) to scale (scale bar = 100 cm). Image by Dan Folkes, from Barker et al. (2021).

Riparovenator and Ceratosuchops are both from the Wessex Formation, the Barremian-age (approximately 129-126 million years old) section of the Wealden that has yielded (and continues to yield) the majority of Isle of Wight dinosaurs (Martill & Naish 2001). Today, we’re mostly going to be talking about a dinosaur from that part of the Wealden that sits on top of the Wessex Formation: the Vectis Formation. The Vectis Formation has its base in the Barremian but is partly Aptian (Aptian: approximately 121-113 million years ago), this meaning that it’s the youngest part of the entire Wealden Supergroup.

Caption: my articles on Wealden dinosaurs (see the list of links below) are typically focused on the Wessex Formation. But today we’re in the Vectis Formation. Image: Darren Naish.

Vectis Formation dinosaurs have been known since the 1860s, the only dinosaurs of the unit known from bony remains being the ankylosaur Polacanthus foxii and the iguanodontian Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis (Martill & Naish 2001). Footprints demonstrate a more diverse fauna, but it’s fair to say that the dinosaurs of the Vectis Formation aren’t well known, and it can be stated with confidence that some reasonable number of new species await discovery in Vectis Formation sediments.

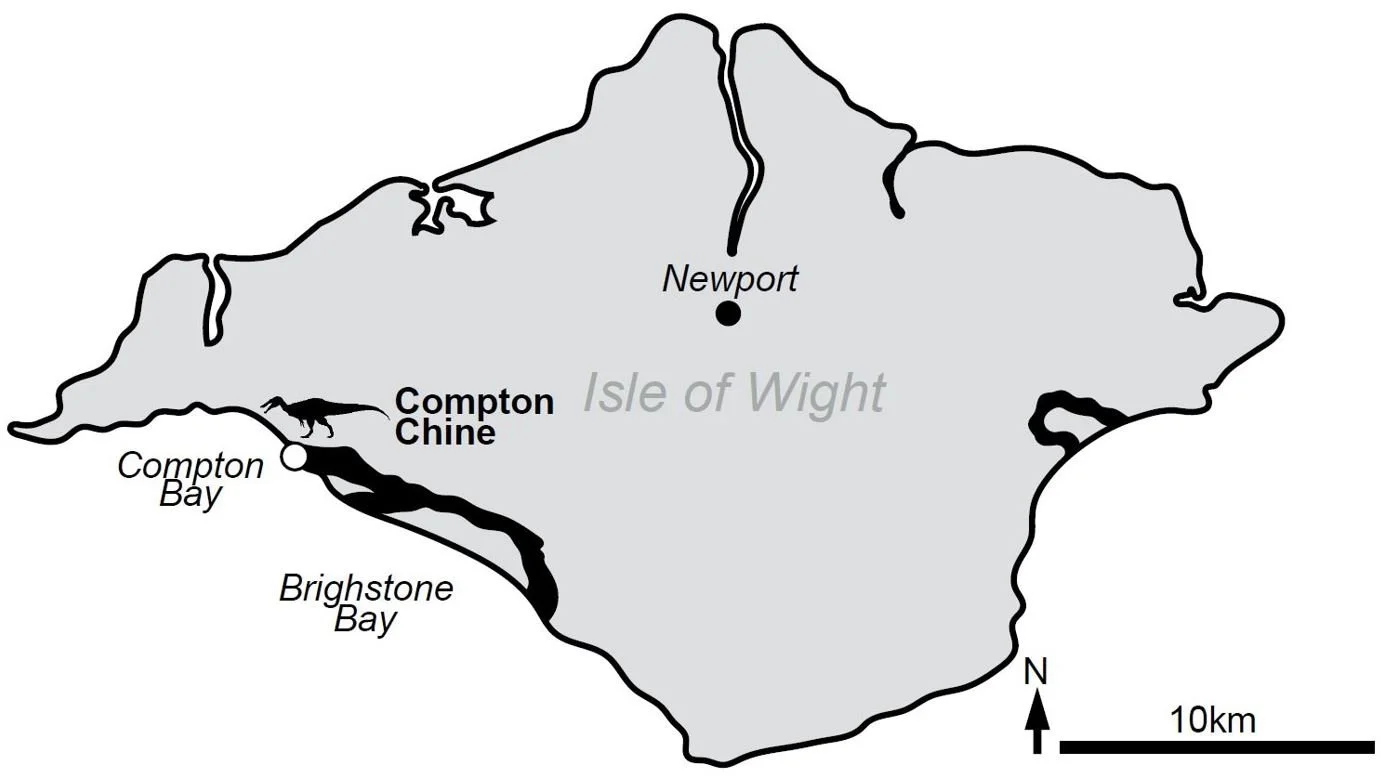

Caption: map from Barker et al. (2022) depicting the discovery location of the White Rock spinosaurid.

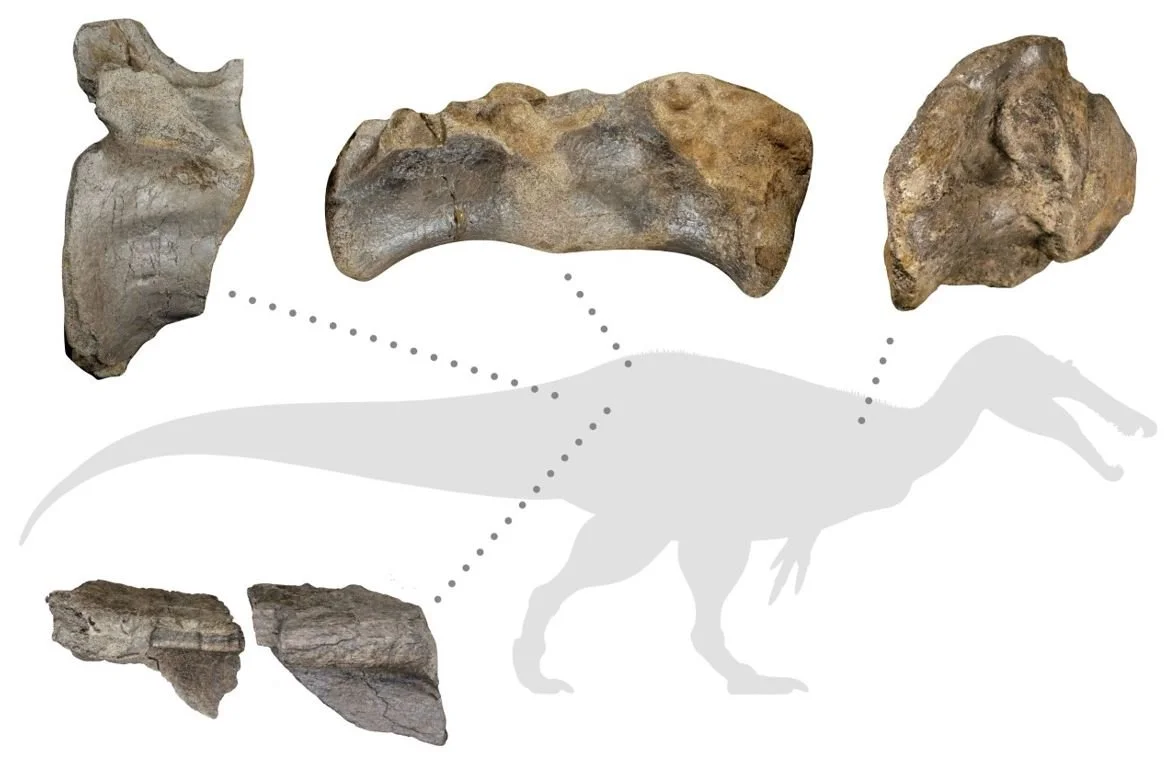

A new Vectis Formation theropod. Over the past several years, local collectors Nick Chase and Mark Penn and Wealden dinosaur specialist Jeremy Lockwood have discovered a number of large dinosaur bones – some near-complete, some fragmentary – along the rocky shore close to Compton Chine on the Isle of Wight’s south-west coast. The bones include an anterior dorsal vertebra, two fused sacral vertebrae, an anterior tail vertebra, rib fragments, sections of the pelvic girdle, fragments of long bone, and a few additional vertebral bits and pieces (Barker et al. 2022). The bones and bone fragments are all LARGE.

Caption: some of my very amateurish photos of the White Rock spinosaurid, included here to help give some idea of the size of these elements. At left, we see the anterior caudal vertebra IWCMS 2018.30.3 in slightly oblique right lateral view (the ‘webbing’ is visible on the side of the neural spine at the top of the image). At upper right (with my hand for scale) we see the two big pelvic fragments (one in its initial, unprepared condition). And at lower right we see the two fused sacral vertebrae IWCMS 2018.30.2 in right lateral view. Combined, their length is 29.8 cm. Images: Darren Naish.

I’m pleased to say that all of these fossils have been accessioned at Dinosaur Isle Museum, Isle of Wight. Here, they were subjected to study by Jeremy, and by myself and colleagues via our association as part of Neil Gostling’s group at the University of Southampton. The study was led by Chris and Neil.

The bones (discovered in approximately the same location) have features which indicate that they come from the same individual: they’re consistent in size, possess anatomical traits indicating that they’re from the same sort of dinosaur, and possess attached matrix showing that they originated (apparently from a single cliff-fall) from the same specific layer, this being an equivalent to the White Rock Sandstone, a unit that forms the base of the Cowleaze Chine Member of the Vectis Formation (Radley et al. 1998, Sweetman 2011, Barker et al. 2022). The White Rock Sandstone represents an environment where narrow river channels met with a lagoonal area.

Caption: image of the White Rock equivalent at Compton Chine, as photographed in June 2022. Image: Chris Barker.

Right away, it was obvious to us that these remains were from a very big tetanuran theropod dinosaur. The vertebrae have pneumatic openings and associated bony laminae typical of theropods (the placement of the foramina matches that of theropods, not sauropods), the anterior dorsal vertebra has the opisthocoelous form (meaning convex at the front, concave at the rear) of big theropods, and the fragment of pelvis – it seems to be the posterior part of the ilium – has the large concavity termed the brevis fossa on its underside. Numerous other theropod features are present across the remains too (Barker et al. 2022). They are not the remains of a sauropod, the only other group of animals that serve as alternative contenders for identification here.

Caption: composite showing the best of the White Rock spinosaurid bones and where we think they come from. Silhouette by Dan Folkes.

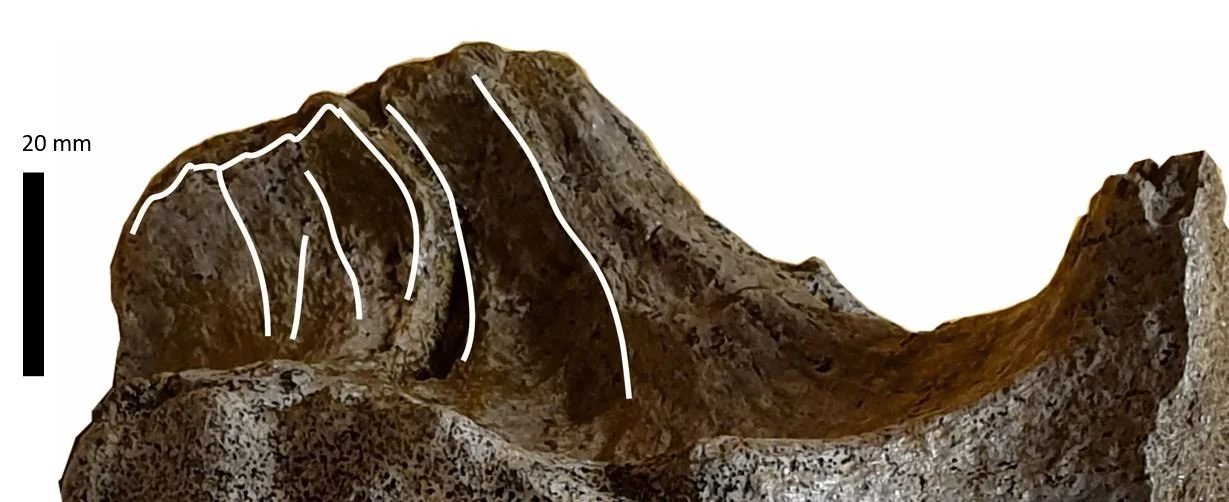

We were intrigued by a number of additional anatomical details in the vertebrae, in particular a flattened rim around the anterior articular face of the anterior dorsal vertebra and an unusual sort of bone ‘webbing’ present at the base of the neural spine on the tail vertebra. These features aren’t widespread in theropods: that flattened rim is a feature of Megalosauroidea (the clade that includes megalosaurids and spinosaurids), and the ‘webbing’ is a spinosaurid trait (a superficially similar feature is also seen in megaraptorans, but they lack various other traits present in the remains).

Caption: crude diagrammatic effort to depict the ‘webbing’ present on the side of the neural spine of the caudal vertebra of the White Rock spinosaurid. It’s an unusual, multi-grooved bone texture that seems to ‘grow on top’ of other bony structures. Image: Darren Naish.

Our conclusion is that these remains are from a spinosaurid, the first reported from the Vectis Formation. That’s significant if you’re especially interested in Wealden dinosaurs.

Do these remains represent a new species? Dinosaur species tend to be unique to specific geological formations, and – based on our knowledge of the entire Mesozoic rock record – tend to last something like one or two or three million years. In addition, there’s no indication from anatomy that these remains belong to any of the previously known Wealden spinosaurids (Charig & Milner 1986, 1997, Naish 2011, Barker et al. 2021, 2022). For these reasons, we can be mildly confident that this is a new animal, and we did at times consider the possibility of giving it a name (cough ‘Vectispinus’).

However, it’s generally a requirement that your animal possesses unique anatomical features – so-called autapomorphies or diagnostic traits – if you want to propose it as a new taxon. Our spinosaurid is extremely fragmentary and doesn’t have unique traits, so we opted to be conservative. For now, we’re calling it the White Rock spinosaurid and leaving it at that.

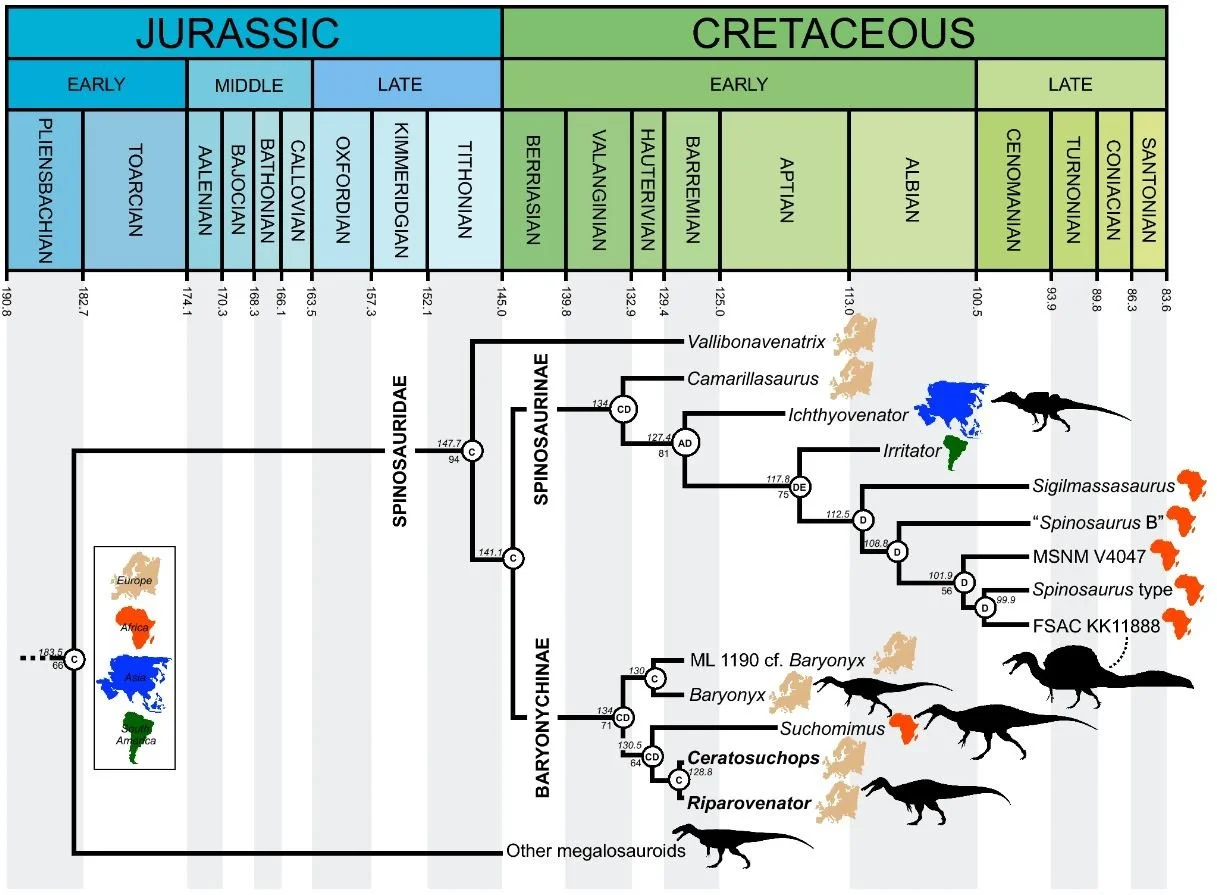

Can we go further in identifying the White Rock spinosaurid? As in: might it be possible to work out exactly what sort of spinosaurid it is? Spinosaurids appear to have diverged early in their history into a baryonychine lineage and a spinosaurine one (this tidy dichotomy is not supported across all studies, and it remains possible that baryonychines are a paraphyletic grade: Evers et al. 2015, Sales & Schultze 2017, Barker et al. 2021, 2022). Members of both lineages are known from the European record, but the European spinosaurines are only known from scrappy remains.

Caption: spinosaurid cladogram from Barker et al. (2021), showing a prominent divergence between Baryonychinae and Spinosaurinae. Image: Barker et al. (2021).

It is thus exciting that the White Rock spinosaurid possesses three details of vertebral anatomy that are seen specifically in spinosaurines (namely, a centrodiapophyseal lamina, prezygodiapophyseal lamina and deep prezygocentrodiapophyseal fossa… yes, vertebral nomenclature does get a little niche at times) (Barker et al. 2021, 2022). Could this animal be a European spinosaurine? That would be in keeping with its giant size, on par with that of Spinosaurus.

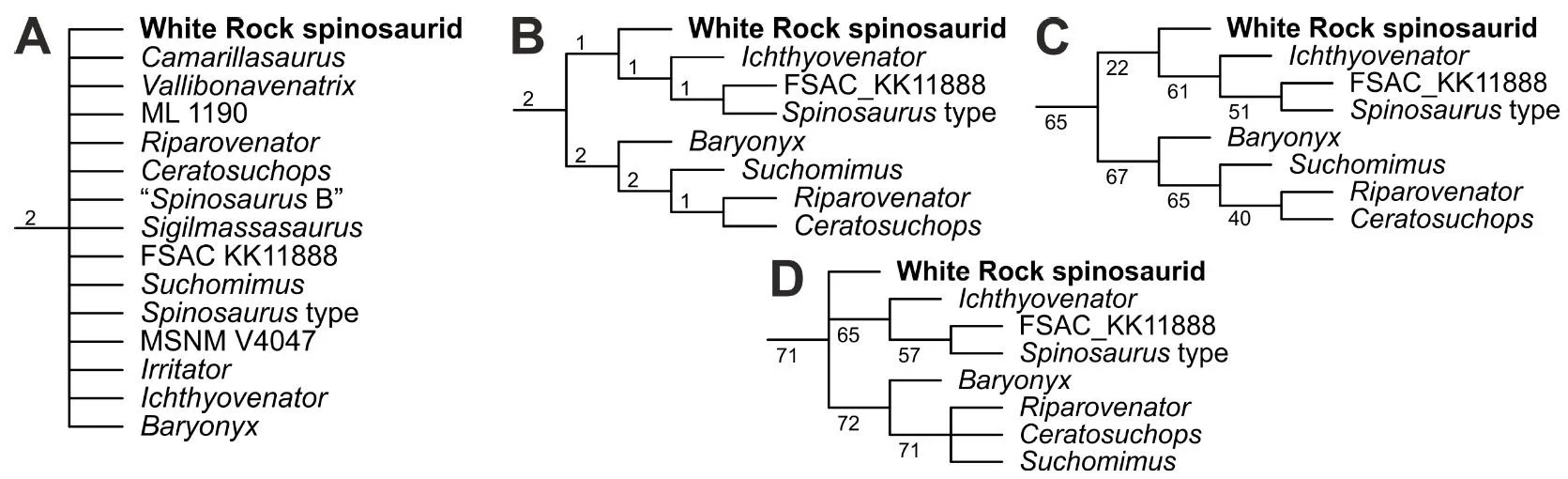

We coded the animal for inclusion in a slightly modified version of the theropod analysis we employed in our previous study (Barker et al. 2021). In some runs, the White Rock spinosaurid was indeed recovered as a spinosaurine. But in others, it occupied a position on the family tree outside of the baryonychine + spinosaurine clade, an equally interesting result (Barker et al. 2022). Ultimately, we again opted to be conservative. We’re not all that confident at the moment that the spinosaurine features present in the White Rock spinosaurid are really, definitely absent from other kinds of spinosaurids and they’re all features that crop up elsewhere in other tetanurans. Maybe the animal will prove to be a spinosaurine eventually, but more data is needed, sigh.

Caption: cladograms depicting the possible position of the White Rock spinosaurid, and the possible topology of Spinosauridae, when the specimen is included in the data set used by Barker et al. (2021). See Barker et al. (2022) for full discussion.

A European giant. I’ve mentioned the size of the White Rock spinosaurid throughout this article, and it’s an issue we discuss at appropriate length in the paper. Yes, this animal was a giant. Its vertebrae (which have centrum lengths of around 16 cm) are on par with (if not longer than) those of Spinosaurus, big specimens of which are thought to have reached or exceeded 15 m in length. The vertebrae are also taller at the posterior articular face than those of Spinosaurus and those of an indeterminate Late Jurassic megalosaurid from Spain previously considered Europe’s largest theropod (Rauhut et al. 2018, Barker et al. 2022). This is backed up by the size of the other White Rock elements.

We haven’t been bold enough to publish a precise length estimate, but the data show that this animal was a giant exceeding 10 m in length, and quite probably the largest theropod yet reported from the European record and among the largest of all time.

Caption: the full version of the image teased above. The White Rock spinosaurid – here depicted as an especially massive, heavily built spinosaurid that is neither clearly a baryonychine or a spinosaurine – is show foraging in a lagoonal, coastal setting, iguanodontians in the background. The carcass represents the Vectis Formation leptocleidid plesiosaur Vectocleidus (described by myself and colleagues in 2012) while the pterosaurs are the remarkable Istiodactylus. Image by Anthony Hutchings.

That just about sums up everything I wanted to say. As ever, we’re left hoping that more remains of this amazing animal come to light in time, hopefully something that exhibits diagnostic traits that allow it to be named and better understood phylogenetically. The animal not only improves our rudimentary knowledge of Vectis Formation dinosaur diversity, it also potentially bolsters previous conclusions on spinosaurid diversity in western Europe (Barker et al. 2022). And as an animal whose remains come from lagoonal sediments, the White Rock spinosaurid perhaps has some bearing on current arguments about spinosaurid ecology and lifestyle… a topic I have cleverly avoided here, ha ha.

As ever, it was a pleasure being part of such a great team, and what happened here is again a good example of what can happen when those who find interesting fossils ensure that they enter the public trust. Thanks to Chris, Neil, Jeremy and the other members of our group for their hard work on this. The White Rock spinosaurid is accessioned at Dinosaur Isle Museum at Sandown, Isle of Wight, who we once again thank for their co-operation and valuable work.

For previous TetZoo articles on spinosaurids, British theropods and associated issues (some links here are to wayback machine versions due to destruction or paywalling of everything at versions 2 and 3), see…

Of Becklespinax and Valdoraptor, October 2007

The world’s most amazing sauropod, November 2007

Oh no, not another new Wealden theropod!, June 2009

Concavenator: an incredible allosauroid with a weird sail (or hump)... and proto-feathers?, September 2010

The Wealden Bible: English Wealden Fossils, 2011, November 2011

Ostrich dinosaurs invade Europe! Or do they?, June 2014 (every archived version of this article lacks the original illustrations, sorry)

Theropod Dinosaurs of the English Wealden, Some Questions (Part 1), March 2020

Introducing ‘Unexpected Isle of Wight Air-Filled Hunter’, a New English Theropod Dinosaur, September 2020

Dr Angela Milner and the Discovery of Baryonyx, August 2021

Two New Spinosaurid Dinosaurs from the English Cretaceous, September 2021

You can support this blog – and my work in general – at patreon.

Refs - -

Charig, A. J. & Milner, A. C. 1986. Baryonyx, a remarkable new theropod dinosaur. Nature 324, 359-361.

Charig, A. J. & Milner, A. C. 1997. Baryonyx walkeri, a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum 53, 11-70.

Naish, D. 2011. Theropod dinosaurs. In Batten, D. J. (ed.) English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 526-559.

Radley, J. D., Barker, M. J. & Harding, I. C. 1998. Palaeoenvironment and taphonomy of dinosaur tracks in the Vectis Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of the Wessex Sub-basin, southern England. Cretaceous Research 19, 471-487.

Sweetman, S. C. 2011. The Wealden of the Isle of Wight. In Batten D. J. (ed). English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 52-78.