In the previous article, we looked at the European, scientific discovery of the Okapi Okapia johnstoni…

Caption: we shouldn’t take it for granted that one of the greatest zoological discoveries of the 20th century is now a relatively accessible animal to those of us able to visit zoological collections. I always take time to look at captive Okapis (here, at Marwell Wildlife, UK). Images: Darren Naish.

We finished with the official recognition of the Okapi as a new living giraffid species in 1901, culminating with the monographing of the species by E. Ray Lankester and others in the first decade of the 20th century. Many of the events in this tale are well known and often repeated in texts that discuss the Okapi’s discovery.

Less well known and far less frequently discussed is the fact that Europeans might actually have been aware of the Okapi’s existence – albeit in the vaguest sense – prior to Harry Johnston’s recovery of those initial strips of skin in 1900. And also poorly known is the fact that the Okapi’s species-level taxonomy has been slightly more controversial than is generally known. As we’ll see, Okapis are quite variable both anatomically and genetically, and it’s worth considering what implications this might have.

A ’pre-Johnston’ European Okapi specimen. Harry Johnston is credited with being the first European to obtain – and submit to scientific investigation – physical remains of the Okapi (see Part 1). But today we know that he was not, actually, ‘the first’. A different skin strip, about 1 m long, was obtained in June 1899 by the Belgian official Lieutenant Léon Vincart from a local chief, who (once back in Belgium) passed it to his brother Alphonse Vincart at the Maredsous Abbey, near Dinant in Belgium. That might seem like an odd place to deposit a strip of Okapi skin, but it held a natural history museum at the time. The specimen is still retained at the abbey today (Raynal 2023). George A. Boulenger – best known for his abundant pioneering publications on reptiles and amphibians – put the specimen on record in a brief note of 1902 (Boulenger 1902).

Caption: the Okapi skin strip collected by Lieutenant Léon Vincart in 1899. Had he succeeding in reporting this specimen in the literature during the year in which he’d found it, he might have won acclaim for its recognition. Image: Jean-Claude Genard, from Raynal (2023).

Incidentally, while Vincart’s Okapi skin specimen is mentioned here and there in literature on the Okapi (e.g., Spinage 1968), the most complete article on it appeared coincidentally within the past few weeks (Raynal 2023). My thanks to Michel Raynal for bringing it to my attention.

While Vincart’s specimen failed to have the same scientific impact that Johnston’s specimens – sent to the Zoological Society of London – most certainly did, it was definitely obtained by a European ‘pre-Johnston’.

Caption: there aren’t that many books that provide good, deep information on Okapis and other giraffids. Here are some that I’ve had reason to consult. Image: Darren Naish.

Other Okapi species. Another Belgian official – Lieutenant Leoni, based in the Haut-Ituri District in what’s now north-eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo – obtained the skin of an adult female and near-complete skeleton of an adult male in 1902, and sent both to Brussels. The local people in the region where Leoni was based knew the animal as the N’dumbe, this being another reminder that ‘Okapi’ was likely a specific term used in one small region and not necessarily the best choice of name for the species as a whole (other names mentioned in the literature of the time include M’Boote and Kenghe; Major 1902, p. 344). The Belgians invited Charles Forsyth Major from the British Museum to examine these specimens. He concluded that they represented a different species from the one identified by Johnston and named it Okapia liebrechtsi after a Commandant Liebrechts… though exactly who Commandant Liebrechts is or what contribution they had to the research wasn’t recorded (Major 1902, Spinage 1968).

A third Okapi species was named in 1902 for the skull and skin of a young adult female that was also deemed different from the original skin strips that Johnston had brought to England. E. Ray Lankester – responsible for publishing the generic name Okapia (Lankester 1902a) (see Part 1) – named this Okapia erikssoni after Lieutenant Karl Eriksson (Lankester 1902b), who had otherwise not been credited for his role in procuring the original specimens (again, see Part 1).

Caption: the Okapia erikssoni holotype as displayed at the British Museum and featured in Lankester (1910). This specimen is otherwise regarded as the first ‘complete’ specimen of O. johnstoni, and today is again treated as a member of that species.

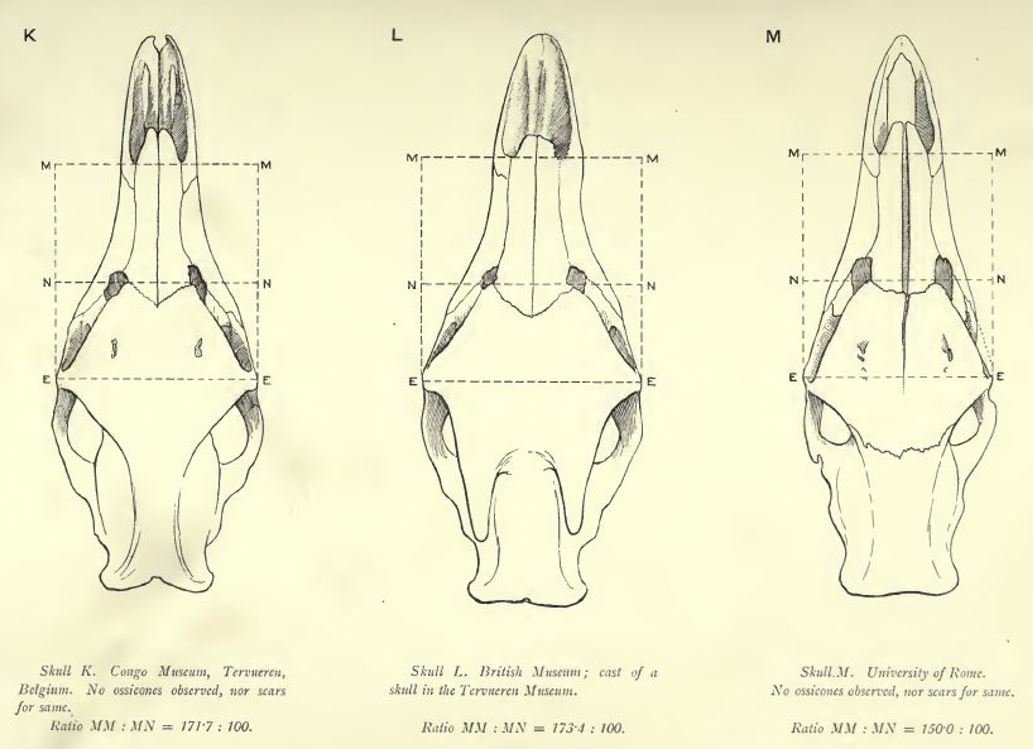

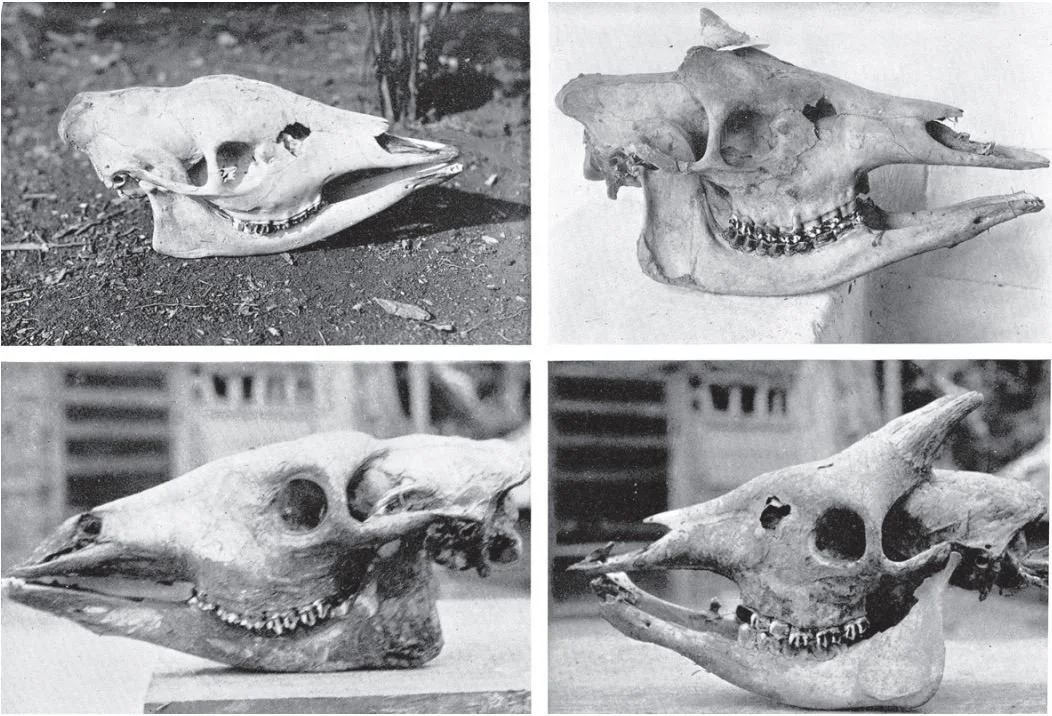

Lankester was seemingly still endorsing the existence of Eriksson’s Okapi when he compiled his 1910 atlas of Okapi anatomy, though it’s hard from that work to find any specific statement on how many Okapi species Lankester thought there might be. In the volume’s preface, Sidney Harmer (Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum) drew attention to Lankester’s figuring of distinct broad- and narrow-skulled forms, the implication being that they might belong to two distinct forms (Harmer said “races”). Lankester himself referred to the O. erikssoni holotype without commentary (Lankester 1910), the implication being that he was still regarding it as valid at that time.

Even as early as 1911, however, the idea that there might be more than one species of Okapi was doubted by others (e.g., Lucas 1911) and the concept was essentially abandoned before the 1920s.

Caption: Lankester (1910) included numerous diagrams of Okapi skulls and used different width : length ratios of various parts of the skull to demonstrate variation. It is difficult to determine from the images alone what this variation represents, since it could be ontogenetic or sexual rather than anything taxonomically significant. Skull L here (in the middle) is a cast of the holotype skull of Okapia liebrechti, named by Charles Forsyth Major in 1902.

The variable Okapi. An additional alleged species – the Kibali okapi Ocuapia kibalensis [sic] – was named in a 1936 book by the Italian explorer and author Attilio Gatti. This animal was said by Gatti (1936) to be especially big, robust and with shorter horns and a different skull shape from other Okapi, though all of this was based on superficial comparisons and there were no formal attempts to establish a type specimen or publish appropriate data. This means that the alleged species has no formal standing.

The generic name ‘Ocuapia’ was not intended as a new genus, since Gatti (1936) used the same spelling for O. johnstoni. I think that Gatti just got it wrong.

Caption: an Okapi skull montage provided by Gatti (1936), showing females at left and males at right, and with the supposedly new ‘Ocuapia kibalensis’ forming the upper row. This montage actually comes from Arment (2018); in the only copy of Gatti (1936) I’ve seen, the male skulls alone are featured.

Needless to say, neither O. liebrechti, O. erikssoni nor ‘Ocuapia kibalensis’ are recognised today. However, could it be that at least one of them might warrant taxonomic distinction after all? One of the points emphasised by Lankester in his 1910 atlas of Okapi anatomy is that the animals are surprisingly variable in skull proportions and pigmentation. Stanton et al. (2014) collected DNA from Okapi faeces, skin clippings, museum specimens and artefacts in Congolese villages and found substantial genetic variation within this animal.

Caption: phylogenetic tree from Stanton et al. (2014), showing genetic variation in Giraffa giraffes (where all eight clades shown here are conventionally recognised as subspecies, and sometimes as species) and Okapi. Note that Okapia consists of two main clades, both of which appear to be genetically diverse. Image: Stanton et al. (2014).

Two main lineages are present within living Okapis, both of which are estimated to have diverged around 1.7 million years ago, and several major divergences between younger lineages on the tree appear to have occurred more than 1 million years ago (Stanton et al. 2014). Other African artiodactyls with lineage divergence dates of this age are mostly (albeit not universally) thought to consist of several subspecies, or even deserve to be split into several or many species.

Stanton et al. (2014) compared Okapi phylogeny and divergence data with that of bushbuck and giraffe subspecies (or species, take your pick) and with duiker species too, the point being that Okapia johnstoni as currently recognised is more genetically variable than artiodactyls universally considered polytypic. Presumably this reflects a history of being split up into refugia during Pliocene and Pleistocene times, but does it mean that there might be some or many Okapi subspecies or even species? Does this genetic variation map well (or at all) with the anatomical variation?

A lot of difficult work would be required to properly sort this out. What this genetic work indicates is that certain Okapi populations require special emphasis in conservation and management. For an animal that’s already in a dire situation with respect to conservation requirements, this is not good news.

Caption: I became interested in seeing how much anatomical variation might exist in the captive Okapis I’ve seen and made a few comparisons. They prove very similar: but that’s expected, since zoo animals (especially within the same geographical area) tend to come from the same source stock, and be closely related. The female Okapi at left is currently on show at London Zoo, the male at right was photographed at Marwell Wildlife in 2022. Images: Darren Naish.

Other claimed early ‘discoveries’. As I mentioned in the previous article, the basics of the Okapi discovery story are well known and often recounted. Less well known is that a few other European people claimed to have encountered Okapis prior to Johnston’s findings of 1900 and 1901. If they’re genuine, they might demonstrate some European awareness of the animal one or two decades earlier. But… are they genuine? I owe my knowledge of these cases to Clive Spinage and his 1968 The Book of the Giraffe for discussion of these accounts.

In 1883, the Russian explorer Wilhelm Junker was in the Nepo Distinct of the Congo when he obtained the complete skin (albeit missing the head and feet) of a hoofed mammal said to be about similar in size to a dwarf antelope, known to some of the locals as the makapi, and suggested by Junker to be a new kind of chevrotain. Junker argued that this was an Okapi skin – surely that of a baby one – which, if true, means that Okapi remains were procured by a European 17 years prior to Johnston’s obtaining the skin bandoliers. Alas, I don’t think we have any way today of testing this claim.

What appears to be a fictitious early European ‘observation’ of the Okapi was provided by Captain James Baptiste Marchand, an officer in the French army, in 1905. Marchand was apparently in the vicinity of Bahr el Ghazel in South Sudan in June 1898 where he was sailing along a tributary of the White Nile in the direction of Kodok, known at the time as Fashoda.

Caption: in case you need help visualising the location of the Bahr el Ghazel region in South Sudan, these maps should help. At left: South Sudan (in green), located to the north-east of Democratic Republic of Congo. At right: the Bahr el Ghazel region (in red) within South Sudan. Images: Martin 23230, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); NordNordWest, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Within the broader context, Marchand’s presence in the region was due to British-French conflict and the colonial Scramble for Africa, and Marchand himself was a veteran of the conquest of both Senegal and what was then known as French Sudan (Mali). Here’s another powerful reminder – as if it were needed – that the European discovery of the Okapi is tightly linked with colonial exploitation and the subjugation of Africans.

Marchard was watching the shore from the deck of his vessel when he observed a remarkable and unusual, beautiful animal seen among a group of antelopes at the edge of a river. It had enormous drooping ears – first likened by Marchand to “horns like the mouflon of Kashmir” – and small horns, and Marchand recognised immediately that it represented a kind of animal as yet unknown to formal zoology. The animal ran away, and Marchand then decided to shoot it, but missed. On seeing a mounted specimen in Paris, he later realised that his mystery Sudanese ‘antelope’ had been one at the same.

But… an Okapi in South Sudan, seen at the edge of the river among a group of antelope? Spinage (1968, p. 144) said that the tale “is far too precise to have a ring of truth about it” and wrote it off as a hoax. I have to concur.

Caption: a very beautiful, very dark male Okapi at ZooParc de Beauval in France. Image: Daniel Jolivet, CC BY 2.0 (original here).

And that’s where we’ll end things. While some Europeans claim to have seen live Okapis, or even obtain physical remains, prior to Harry Johnston’s discovery of 1900, these are of dubious standing, the exception being Léon Vincart’s recovery of a skin segment in 1899. And while early arguments about Okapi species-level taxonomy have mostly been forgotten in recent decades, phylogenetic work on Okapi diversity implies that there may come a time when this issue needs revisiting.

Needless to say, much more could be said about Okapis: in particular, about their ecology, behaviour and conservation status. I would like to come back to those issues in time, so hold that thought.

For previous mentions of Okapis at Tet Zoo, and other giraffid-themed writings, see…

Giraffes: set for change, January 2006

More on what I saw at the zoo, June 2006

Stuffed megamammal week, day 3: Okapi, April 2009

Inside Nature’s Giants part IV: the incredible anatomy of the giraffe, July 2009

Because giraffes are heartless creatures, and other musings, January 2012

Burning Question for World Giraffe Day: Can They Swim?, June 2016

The Discovery of the Okapi, Part 1, April 2023

Refs - -

Arment, C. 2018. Profiles in cryptozoology: Commander Attilio Gatti. BioFortean Notes 6, unpaginated.

Boulenger, G. A. 1902. Fresh record of the okapi. The Field 99, 823.

Gatti, A. 1936. Great Mother Forest. Hodder and Stoughton, London.

Lankester, E. R. 1902a. On Okapia, a new genus of Giraffidae, from Central Africa. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 16, 279-307.

Lankester, E. R. 1902b. The specific name of the Okapi presented by Sir Harry Johnston to the British Museum. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, series 7, 10, 417-418.

Lankester, E. R. 1910. Monograph of the Okapi. Trustees of the British Museum, London.

Lucas, F. A. 1911. [Review of] Monograph of the Okapi. Science 33, 65-66.

Major, C. I. F. 1902. On the okapi. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1902, 73-79.

Raynal, M. 2023. Eine Okapi-Haut im Jahr 1899. Jahrbuch für Kryptozoologie 3 (3), 279-282.

Spinage, C. A. 1968. The Book of the Giraffe. Collins, London.