A group of passerine birds often framed as a bit boring and samey are no such thing…

Caption: the Eurasian skylark Alauda arvensis, the ‘classic lark’ for those of us in Europe. Image: Frebeck, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Among the many passerine groups of the world are the larks, known technically as alaudids. Larks are hugely widespread, occurring on all continents excepting South America* and the polar regions, and all are strongly associated with deserts, semi-deserts, steppes and savannahs. A few species – most famously the Eurasian Skylark Alauda arvensis – also exploit farmland, since monotone fields obviously have a strong similarity with the steppe-like environments these birds prefer.

* I had forgotten that the Horned lark occurs in northern South America; see comments.

The caveat on lark distribution is that it’s a little misleading to describe them as denizens of (nearly) all continents given that only a single species (the Horned or Shore lark Eremophila alpestris) occurs in North America, while another singleton (Horsfield’s bush lark or Australasian lark Mirafra javanica) is the sole representative of the group in Australia. The caveat to that caveat is that the Horned or Shore lark is likely a species complex, and the same might be true of the variable Horsfield’s bush lark as well. Another caveat on distribution is that the group is predominantly African, 80% or more of the c 100 extant species occurring on the continent.

Caption: a lark montage, showing members of groups that might be considered ‘typical’ within the family. Left to right: Horsfield’s bush lark or Australasian lark Mirafra javanica, Temminck’s lark Eremophila bilopha, Rufous-tailed Lark Ammomanes phoenicurus. Images: JJ Harison, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here); J. M. Garg, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here).

Having just written about ‘bush larks’ I have to note here the inconsistency that exists in the names of these birds. Certain species have common names that are often or usually concatenated. Examples include woodlark, skylark and bushlark. The same names, however, are sometimes written as two words: wood lark, bush lark and so on. Bird vernacular names are more standardised than the names of virtually all other animal groups (largely because bird experts are a very…. thorough lot). Even so, there’s frustrating inconsistency here.

Lark basics. Larks are generally brown, pale ventrally, highly cryptic and good at concealing themselves when on the ground. Head crests have evolved several times and take the form of elongate, erectile feathers on the top of the head (as in the Skylark and Galerida crested larks) or paired, horn-like structures on either side of the crown (as in the Eremophila horned larks, where the crests form part of a boldly patterned series of facial markings). Larks are generally long-legged and good at running and walking. A long hallux claw – an often prominent feature of ground-adapted passerines – is present in many, and the other claws are often long and fairly straight as well.

Caption: among my favourite larks is the Greater hoopoe-lark Alaemon alaudipes, and I’m lucky enough to have seen it in life. That explains the photo shown here on the left: it was taken by my friend Richard Hing while we were on a palaeontological expedition in Morocco (a region great for larks). At right, a sharper image of the same species (albeit a different subspecies), this time photographed in Gujarat, India. Images: Richard Hing; Sumeet Moghe, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Caption: I distinctly remember the few occasions in which I saw hoopoe-larks in the Sahara, and this photo is included because it gives some idea of the habitat in which our sightings mostly occurred. The birds were in flat, mostly open areas with scant nearby scrubby vegetation. This one was actually photographed about 10 m away from the tents of a group of nomadic people. Image: Richard Hing.

You might assume that larks are dull, samey, brown birds. But that’s not true or fair since the group include a list of really interesting, exotic species that rank among the most notable and unusual of passerines. My favourites include the large, leggy, tall, long-billed Greater hoopoe-lark Alaemon alaudipes of northern Africa, the Middle East and western Asia, and the fabulously thick-billed, cursorial, err, Thick-billed lark Ramphocoris clotbey of north-west Africa and the Middle East. A novice to passerine classification and diversity would be surprised that these finch-like and vaguely hoopoe-like birds are included in the same family as ‘classic’ larks like skylarks.

Caption: an artistic rendition of a Thick-billed lark Ramphocoris clotbey that doesn’t really do a good job of showing it in a natural posture. This image is from H. E. Dresser’s 1871 A History of the Birds of Europe, Volume 4. I really like Dresser’s books and just looked into the possibility of buying them. But I just learned that you can’t really buy them for less than £850. Guess I’ll stick with the pdfs then.

Here in the UK, larks like skylarks are famously associated with ‘the countryside’ and their melodious and energetic song-flights are characteristic of healthy farmland, meadows and heaths. It’s easy to hear them in such places but finding them in the sky can be hard. Unsurprisingly, skylarks are referenced in various old poems and rhymes, and they were formerly kept frequently as cage birds for their song (Greenoak 1997).

Caption: Alan Harris’s skylark painting from the cover of Paul Donald’s 2004 book The Skylark. Image: (c) Alan Harris.

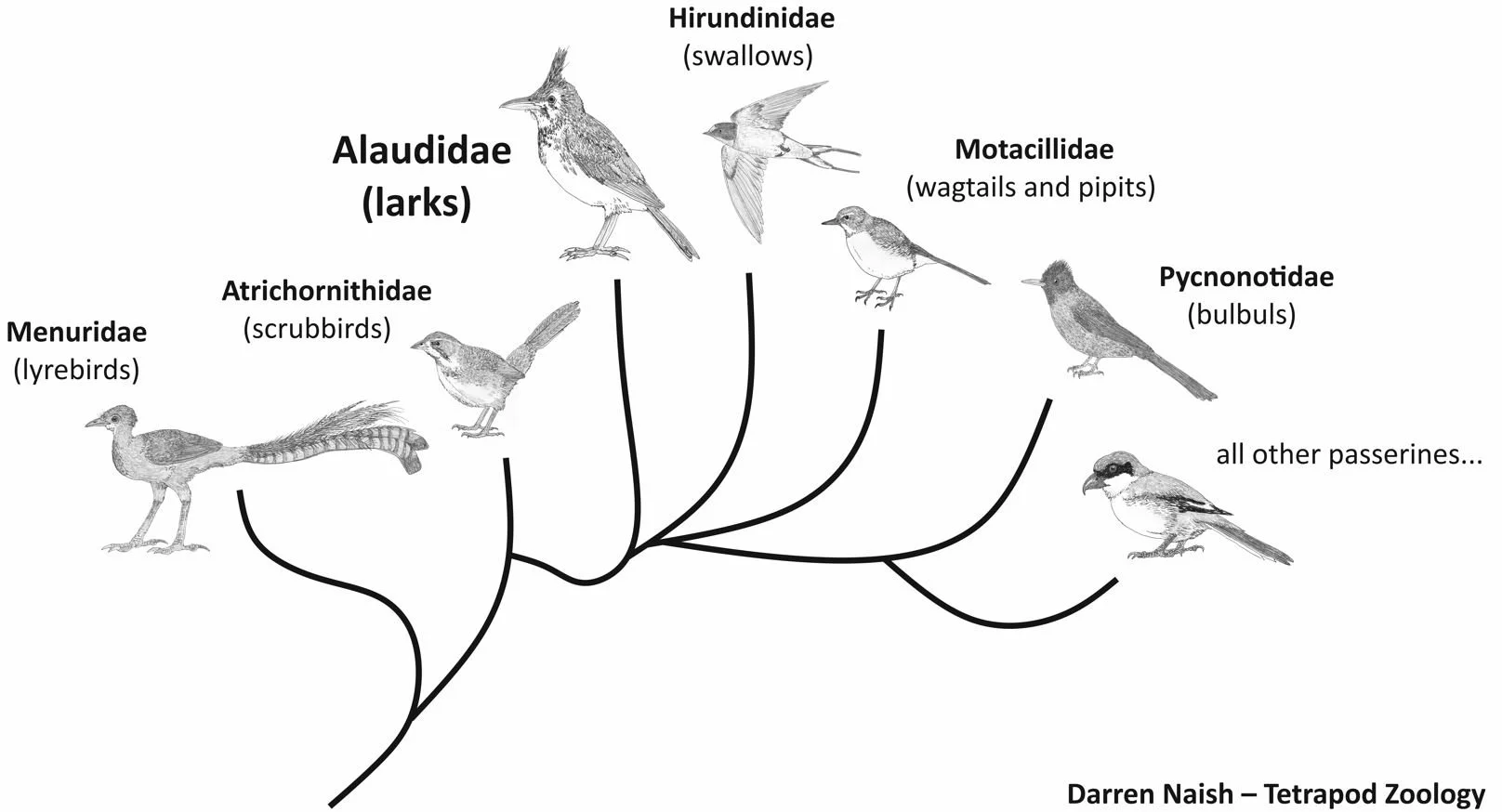

Placing larks in the oscine tree. It’s long been obvious that larks are oscines: part of the huge passerine clade that includes crows and their allies as well as Passerida, the warbler-sparrow-flycatcher group. The traditional view most familiar to me during my student years is that larks are anatomically nondescript, even ‘primitive’, relative to oscines as a whole, and potentially something like ‘living fossils’ within the group. This view is owed to the fact that larks look anatomically archaic relative to most other oscines: there’s only a single pneumatic opening in the humerus (as opposed to two or more), the tarsus is latiplantar (meaning rounded on its posterior surface, rather than acutiplantar) and with scutes on both its posterior and anterior surfaces, and the syrinx lacks – or possesses in only rudimentary form – the midline structure termed the pessulus otherwise common in oscines (Sibley & Ahlquist 1990).

It's for these reasons that larks have ‘conventionally’ been placed or listed outside the clade that contains all warbler-like, sparrow-like and flycatcher-like oscines. Alexander Wetmore promoted this view in his highly influential classification of birds published in 1960, and it explains why larks – sometimes together with hirundines (swallows and martins) and also motacillids (pipits and wagtails) – are virtually always placed first among oscines in books that arrange passerines by family. In those books that include the Australasian lyrebirds and scrubbirds, larks are listed after those two ‘more archaic’ families.

Caption: a representation of oscine phylogeny as it was generally imagined throughout most of the 20th century. Lyrebirds and scrubbirds were posited as the earliest of the oscine lineages to diverge (a position they still occupy today), while larks, swallows and wagtails were all considered close, close to the ancestry of all ‘more advanced’ passerines, and also as ‘early-diverging’ in the tree. Several bird books from the 1960s, 70s and 80s depict this sort of thing and it’s also reflected in the way families are listed in fieldguides. The images you see here were produced for my in-prep textbook, the completion of which can be supported via my patreon.

A number of contradictions always implied that this ‘archaic position’ was wrong. The finch-like bills of certain larks mean that a few authors once considered them allied to weavers or similar birds, and a reduced 10th primary led some to regard larks as close to the ‘nine-primaried oscine’ group, some members of which have finch-like bills. It has to be said that these proposals were themselves contradicted by a list of other anatomical features, however.

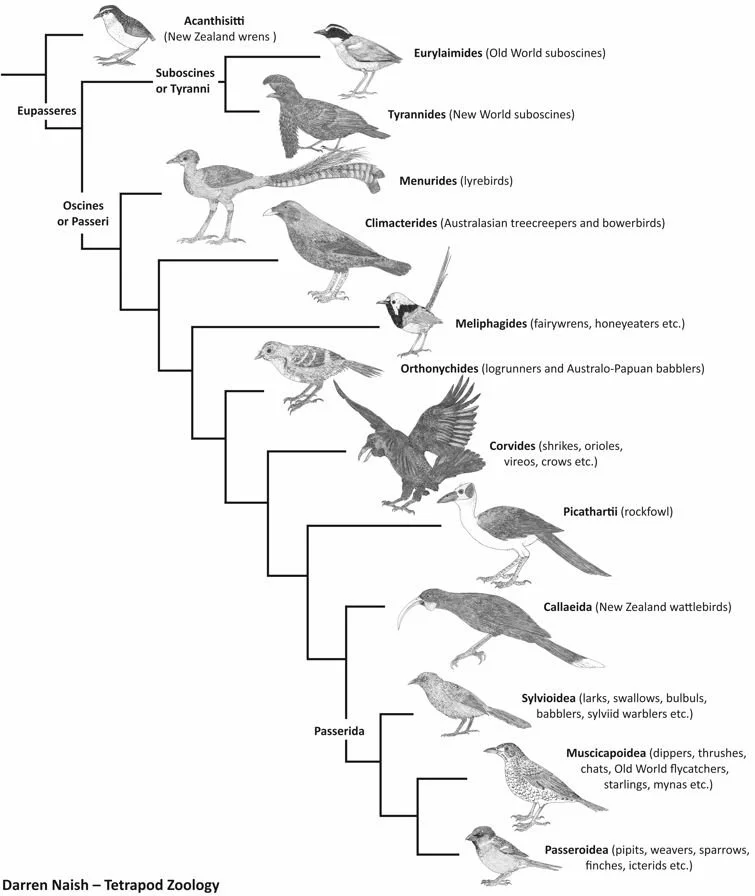

Today, molecular results show that larks are deeply embedded within oscines – not located at or close to its root – and part of the ‘flycatcher-like’ clade Sylvioidea or Sylviida (Cracraft 2014, Fregin et al. 2012, Selvatii et al. 2015). Within that clade, they’re close to, and surrounded by, groups like babblers, acrocephalid and locustellid warblers and – surprisingly – are close to reedlings (Panuridae) (Cracraft 2014, Fregin et al. 2012, Selvatii et al. 2015).

Caption: increasingly complex versions of my passerine phylogeny image have appeared at Tetrapod Zoology over the years, and here’s the latest iteration. The topology here is based on that of several recent studies (e.g., Selvatii et al. 2015) and the taxonomy partly follows that of Cracraft (2014). The images you see here were produced for my in-prep textbook, the completion of which can be supported via my patreon.

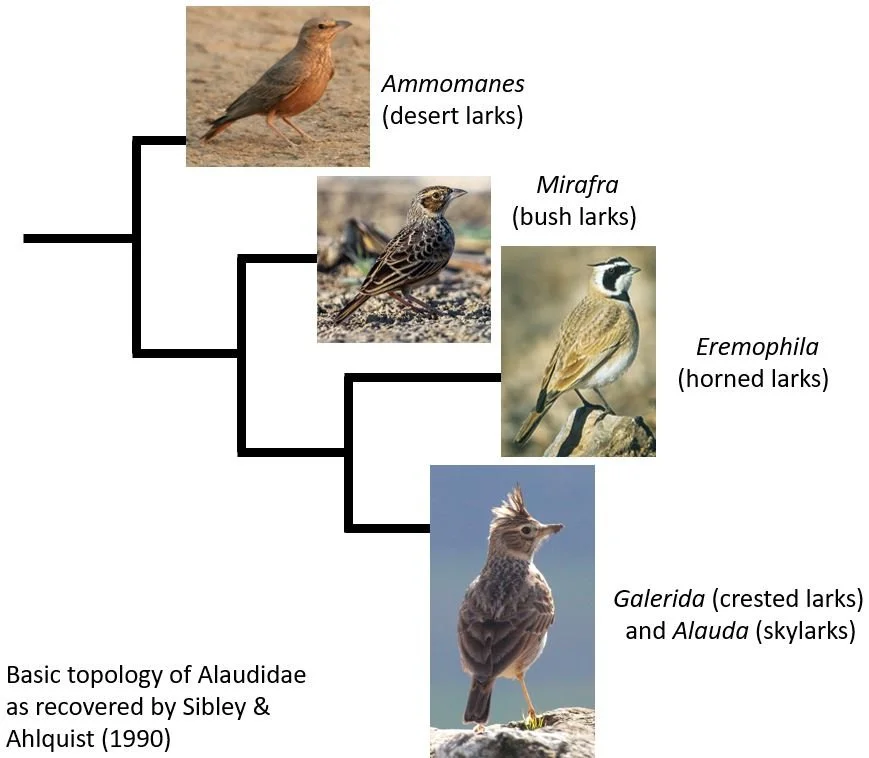

Abundant surprises in lark phylogeny. Moving now to phylogenetics within the lark family, it turns out that things are more complex, and more interesting, than conventionally thought. Few studies of lark phylogeny exist. Sibley & Ahlquist (1990) included data from a few taxa and found Ammomanes (desert larks), Certhilauda (long-billed larks) and Mirafra (bush larks) to be part of early-diverging lineages outside a clade that includes Eremophila (horned larks), Galerida (crested larks) and Alauda (skylarks). A far more comprehensive job of analysing larks was published by Alström et al. (2013); they recovered a phylogeny similar in approximate structure to that of Sibley & Ahlquist (1990) but reported the following novelties.

Caption: simplified lark phylogeny, based on that presented by Sibley & Ahlquist (1990). Images (in branching order): J. M. Garg, CC BY-SA 4.0 (original here); JJ Harison, CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here); Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here); Bob Loveridge, used with permission.

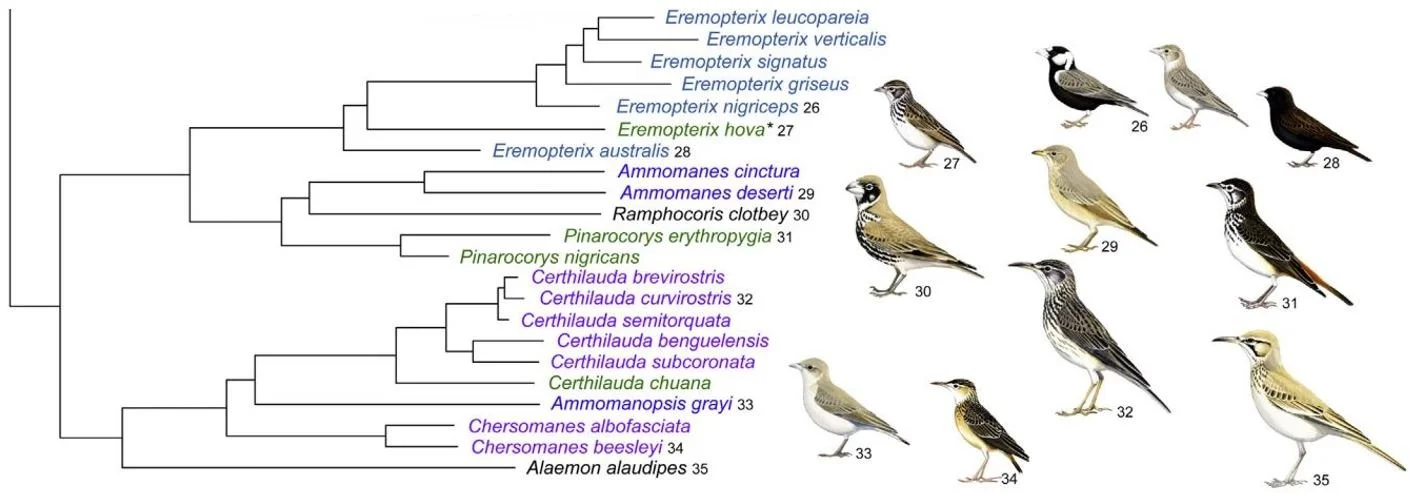

Firstly, several genera proved non-monophyletic, Ammomanes and Mirafra among them. Clades considered good honest genera are located in ‘between’ the newly separated segments of the respective former genera, meaning that new (or resurrected) genus-level names are needed. For Ammomanes, this has meant resurrection of Ammomanopsis (originally coined in 1905) for Gray’s lark A. grayi from south-west Africa; for Mirafra, it’s meant that some species are best considered to belong to other genera, like Eremopterix (Alström et al. 2013). Here, it’s worth making the point that many (dare I say… most?) polytypic passerine genera have proved non-monophyletic when sufficiently well sampled, which isn’t a surprise given that most passerine genera have spent the bulk of their lives in the literature as ill-defined dumping grounds for species that look only approximately alike.

Caption: Gray’s lark might look like it should be included in Ammomanes, but genetics shows that it’s not. It’s not close to the Ammomanes species at all, but is instead part of the clade that otherwise includes the slender-billed Chersomanes and Certhilauda larks. Image: J. G. Keulemans, in public domain.

Secondly, certain taxa previously considered close allies based on morphology proved to be distant relatives. A good example is provided by the African Spizocorys larks and the mostly Asian Calandrella short-toed larks, two genera that are incredibly similar and have mostly been considered congeneric over the past several decades. But Spizocorys isn’t close to Calandrella at all: the former is part of the same clade as crested larks and skylarks, while short-toed larks are close kin of horned larks and the Bimaculated lark Melanocorypha bimaculata and kin (Alström et al. 2013). This discovery is pretty disturbing if you think that the external look of an animal is a good guide to its affinities.

What this means is that highly similar species classified within these disparate genera occur as geographically distinct ‘species pairs’. Alström et al. (2013) pointed to Dunn’s lark Eremalauda dunni (of northern Africa and western Asia) and Stark’s lark S. starki (of south-west Africa) as one such convergently similar, disjunct yet distantly related pair, and a similar situation exists for Dupont’s lark Chersophilus duponti of the Iberian Peninsula and northern Africa and the Certhilauda larks of southern Africa. We’re familiar with the idea of surprising convergence explaining the similar appearance of well-separated distant cousins – marsupial possums and squirrely rodents, say – yet here’s surprising convergence happening in the same family-level group.

Caption: Eremalauda and Spizocorys species look sufficiently alike that they’ve mostly been considered congeneric. But molecular data indicates that they’re not especially closely related. Images: Opisska, OA (original here); Alastair Rae, CC BY-SA 2.0 (original here).

Thirdly (and finally), taxa that do seem to be close relatives are very different in anatomy. Spizocorys might not be close to Calandrella, but it is close to the Woodlark Lullula arborea, which is a surprise given the slim, straight form of the Woodlark bill relative to the far stouter, deeper, Calandrella-like bill of Spizocorys. Meanwhile, Ramphocoris – the uberthickbill we looked at earlier – is close to the skylark-like Pinarocorys and Ammomanes desert larks, which is again not what you’d expect. I’d previously imagined an affinity with the Melanocorypha larks given a few similarities, and indeed Ramphocoris was originally included in Melanocorypha when first scientifically named in 1850.

Caption: one of the several lark clades identified by Alström et al. (2013). Note that Ramphocoris is close to desert larks and to superficially skylark-like taxa. Meanwhile, hoopoe-larks and other slender-billed taxa form a sub-clade within the same clade... as is Ammomanopsis. Image: Alström et al. (2013).

Rather than being predictable and conforming to guesses based on gross morphology, it turns out that lark phylogeny is complex, with unexpected groupings and convergences aplenty. In fact, the study that’s most responsible for establishing this – Alström et al. (2013) – has made larks into potential poster-kids for ‘cryptic complexity’ (if I may), and one of the best examples of this sort of thing in bird history. Which is a fine turn-up for the books in a group so often considered samey and conservative.

And that’s not all. More on larks coming soon.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on passerines, see…

Great tits: still murderous, rapacious, flesh-rending predators!, February 2013

For The Love of Crows, October 2015

Thoughts on the Passerine Tree, 2016, October 2016

A Battle Among Blue Tits, February 2018

Cocks-of-the-Rock, Extreme Cotingas, April 2019

Birdwatching in Suburban China, May 2019

Tell Me Something Interesting About Dunnocks, July 2019

Suburban Birdwatching in Queensland, Australia, November 2019

Kirk W. Johnson’s 2018 The Feather Thief, a Review, February 2021

The Locustella Warblers, May 2021

Chiffchaffs and What Are 'Old World Warblers' Anyway?, February 2022

Surprising Diet of the House Sparrow, August 2022

Refs - -

Alström, P., Barnes, K. N., Olsson, U. Barker, F. K., Bloomer, P., Khan, A. A., Qureshi, M. A., Guillaumet, A., Crochet, P. A. & Ryan, P. G. 2013. Multilocus phylogeny of the avian family Alaudidae (larks) reveals complex morphological evolution, non-monophyletic genera and hidden species diversity. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 69, 1043-1056.

Cracraft, J. 2014. Avian higher-level relationships and classification: Passeriformes. In Dickinson, E.C. & Christidis, L. (eds) The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World (fourth edition), Volume 2: Passerines. Aves Press, Eastbourne, pp. xvii-xlv.

Fregin, S., Haase, M., Olsson, U. & Alström, P. 2012. New insights into family relationships within the avian superfamily Sylvioidea (Passeriformes) based on seven molecular markers. BMC Evolutionary Biology 12, 157.

Greenoak, F. 1997. British Birds: their Folklore, Names and Literature. Christopher Helm/A & C Black, London.

Selvatti, A. P., Gonzaga, L. P. & Russo, C. A. M. 2015. A Paleogene origin for crown passerines and the diversification of the Oscines in the New World. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 88, 1-15.

Sibley & Ahlquist 1990. Phylogeny and Classification of Birds: a Study in Molecular Evolution. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.