For something like four decades, Dr Alan Feduccia of the University of North Carolina has been arguing that everyone is wrong about dinosaurs….

Feduccia’s primary contention – expressed in technical papers and opinion pieces but mostly in his books The Origin and Evolution of Birds (Feduccia 1996) and Riddle of the Feathered Dragons (Feduccia 2012) – has been, and remains, that birds cannot have evolved from theropod dinosaurs but instead have their origins in non-dinosaurian, climbing quadrupedal reptiles of the Triassic. He holds this view because he regards theropods as too specialized for terrestrial, cursorial life and because he contends that birds, bird flight and feathers can only have evolved in an arboreal, ‘trees down’ setting.

Caption: the Feduccian oeuvre, these books being (left to right) from 1996, 2012 and 2020. The more recent works have a fringe, contrarian taint.

Unfortunately for Feduccia, the ‘birds are theropods’ paradigm is well supported and firmly embedded within the modern view of what dinosaurs are. Not only is the origination of birds regarded as a significant event within dinosaurian history, worse is that aspects of avian anatomy, behaviour and biology have been identified in, and extrapolated for, dinosaur groups of all sorts. Put another way, the view that non-bird dinosaurs were near-avian is very much part of mainstream thinking.

Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs: Forays in Postmodern Paleontology (RTBAD from hereon) is not an instruction manual for palaeozoophiles, nor does it include homage or reference to the 1984 movie Romancing the Stone. Rather, it’s composed of 23 essays on the state of dinosaur science as Feduccia sees it today. The title is inspired by Feduccia’s idea that he’s responding to John Ostrom’s 1987 ‘Romancing the dinosaurs’, an odd choice given that Ostrom’s article can’t be considered familiar or influential. Discussions on bird origins are in the book but this might not be obvious, since about a third of its content (chapters 1-7) is devoted to criticism of work on dinosaurian physiology, on what dinosaurs are, and on the popularization of dinosaurs that has occurred since the Dinosaur Renaissance of the 1960s through to the 90s. Chapters 8-11 are mostly devoted to contentious issues in bird evolution, like palaeognath biogeography and paedomorphism, and avian digit homology.

Caption: alas, Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs does not include dating advice, no matter how alluring those sexy dinosaurs might be. Image: Lyn Joyce, used with permission.

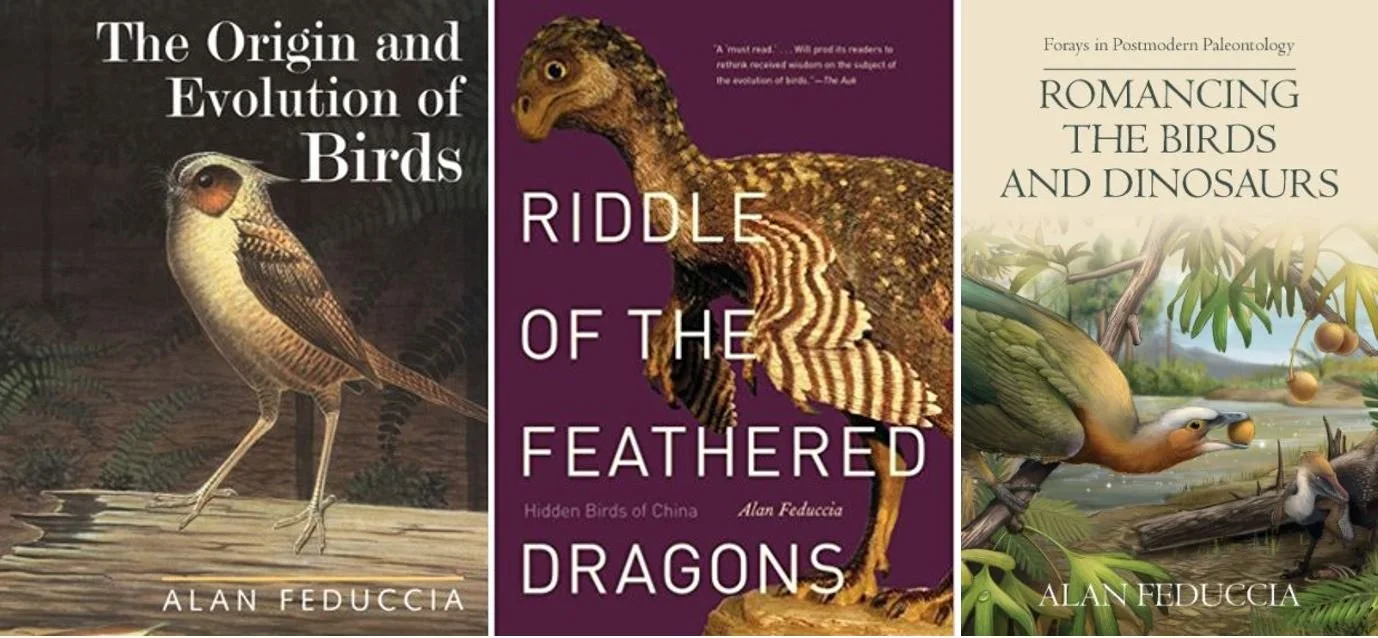

Finally, chapters 12-21 reinterpret the feathered theropods of the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Those with hair-like filaments (like little Sinosauropteryx) do not really have a filamentous pelt, Feduccia argues, but are covered in misidentified collagen fibres. Those regarded as bird-like non-birds (the turkey-like Caudipteryx, four-winged Microraptor and so on) are, Feduccia contends, misidentified members of the avian radiation, or (in the case of the small scansoriopterygids) not theropods at all. The last two chapters include thoughts on the end-Cretaceous extinction event, and a summary and call to arms.

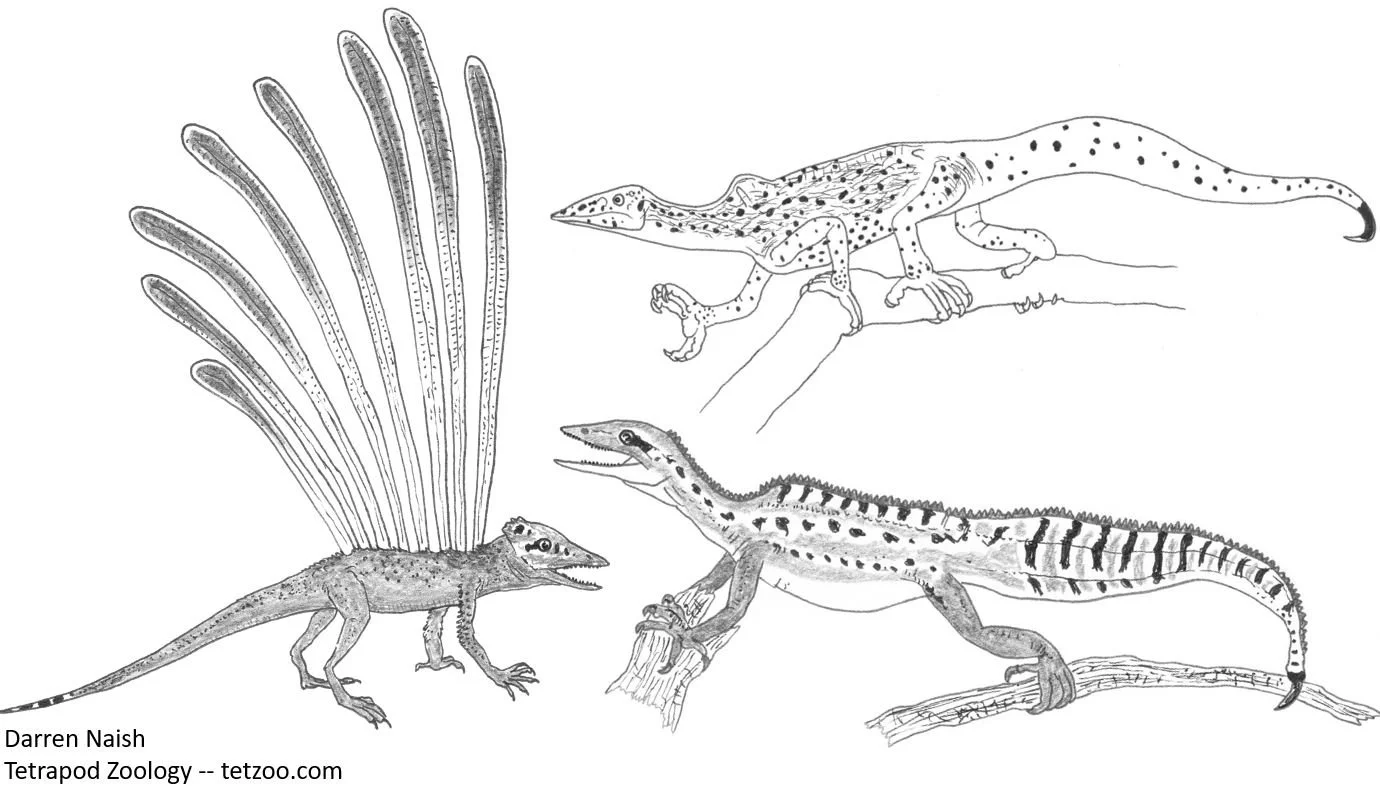

Caption: a few of the main theropod taxa that get extensive mention in RTBAD. All belong to the theropod group Coelurosauria. Caudipteryx and Microraptor belong to the coelurosaurian group Maniraptora. Image: Darren Naish.

What is RTBAD all about, exactly? RTBAD can best be summarized as an effort to show that the view of dinosaurs promoted by specialists is chaotic, shallow and unthinking, and driven by a quest for popularity and an adherence to cult cladism.

Most modern books on fossil animals celebrate the current golden age of palaeontological discovery. RTBAD, in contrast, is infused with negativity and devoted to the idea that palaeontologists are mostly wrong about everything. Said palaeontologists are part of a cabal where essentially all work being done on bird-like dinosaurs and dinosaur-like birds is driven by an extreme form of confirmation bias: Feduccia accuses palaeontologists of practising a ‘theory-laden’, ‘monolithic’ science, and states repeatedly that conclusions are made to “accommodate the cladogram”, to fit predetermined narratives that are based on phylogenetic hypotheses. Feduccia misses the irony that his own research is transparently driven by an even more targeted form of confirmation bias than the one he erroneously identifies in others. In his efforts to show that the avian hand is not homologous with the theropod one, that integumentary filaments on theropods must be collagen fibres, and that Caudipteryx and other feathered dinosaurs are members of the avian radiation, Feduccia’s research programme has been devoted to verifying his ‘birds are not dinosaurs’ position. To this end, he has been unsuccessful, as he admits himself, at one point lamenting that his previous book “never gained popularity among paleontologists” (p. 311).

Caption: I will say this for Alan Feduccia… his books do feature some nice artwork (thinking in particular of the pieces by John P. O’Neill). The cover of RTBAD features this excellent image by Qiuyang Zheng, showing a fruit-eating jeholornithid bird while a terrestrial dromaeosaurid forages nearby. Image: (c) Qiuyang Zheng.

Because science and scientists welcome and celebrate scepticism, error-correction and out-of-the-box thinking, an argument can be made that Feduccia’s role is valuable, perhaps necessary. Throughout the book, Feduccia opines that he and a select band of colleagues are the true scientists here, the ones with a proper methodology, the ones practising true, honest scepticism, and the ones who work independently of trends in popular culture. They alone can guide the reader through the fickle, shallow, chaotic mess of claims made about dinosaurs and archaic birds by the scientifically naïve, power-hungry, juvenile popularists of our age. Why, some of these people “have Twitter accounts with large followers [sic], dealing with everything from paleontological discoveries to sports and politics!” (p. 21). Take that, Steve Brusatte!

The preface and early chapters of RTBAD are devoted to the admonishing of modern palaeontology and palaeontologists (Chapter 1: ‘Burning dim: the new theory-laden study of fossils’; Chapter 2: ‘The road to paleontological postmodernism’; Chapter 3: ‘Make it new! The dinosaur renaissance’). I’m among the terrible people that Feduccia has in mind here and receive appropriate excoriation. I especially enjoy Feduccia’s inability to apply due diligence to an article I published on April 1st (‘Mass Survival of Multitudinous Dinosaur Lineages across the K–Pg Boundary’).

Caption: there are several reasons for the cessation of my April 1st articles, and one of them is that some people were and are unable to recognise them as parody. Tricking mokele-mbembe truthers is one thing, but catching a Distinguished Professor Emeritus hook, line and sinker is another. I feel so guilty.

Alan Feduccia, j’accuse. But try as I might to think of the author as a wise sage and friend of the reader, the fact is that RTBAD is cartoonishly overloaded with bias and dirty tricks. Whataboutism, intellectual dishonesty, erroneous repetition, strawmanning and naïve falsification appear throughout as the author aims to diminish positions he dislikes, the most vehement of his arguments representing nothing more than personal incredulity.

‘Whataboutism’ is the arguing tactic whereby facts and issues tangential to the matter at hand are mentioned in an effort to weaken an opponent’s position. The composite ‘Archaeoraptor’ and the misidentified Oculudentavis (pp. xii-xv) represent crass errors it’s true, and it’s also true that some theropod fossils have been reinterpreted, sometimes many times (pp. 5-6). Feduccia’s point in discussing these is to show that the scientists behind them are trying to install themselves as “new authority figures” (p. xii), and that a sort of cladistic fundamentalism has taken over. All I see is scientists trying to do science, and sometimes making mistakes. It’s not fair to say that Feduccia behaves like a creationist, but it’s difficult to avoid this comparison given that those repeat references to ‘Archaeoraptor’ look awfully similar to that eternal creationist trick of never failing to mention Piltdown man.

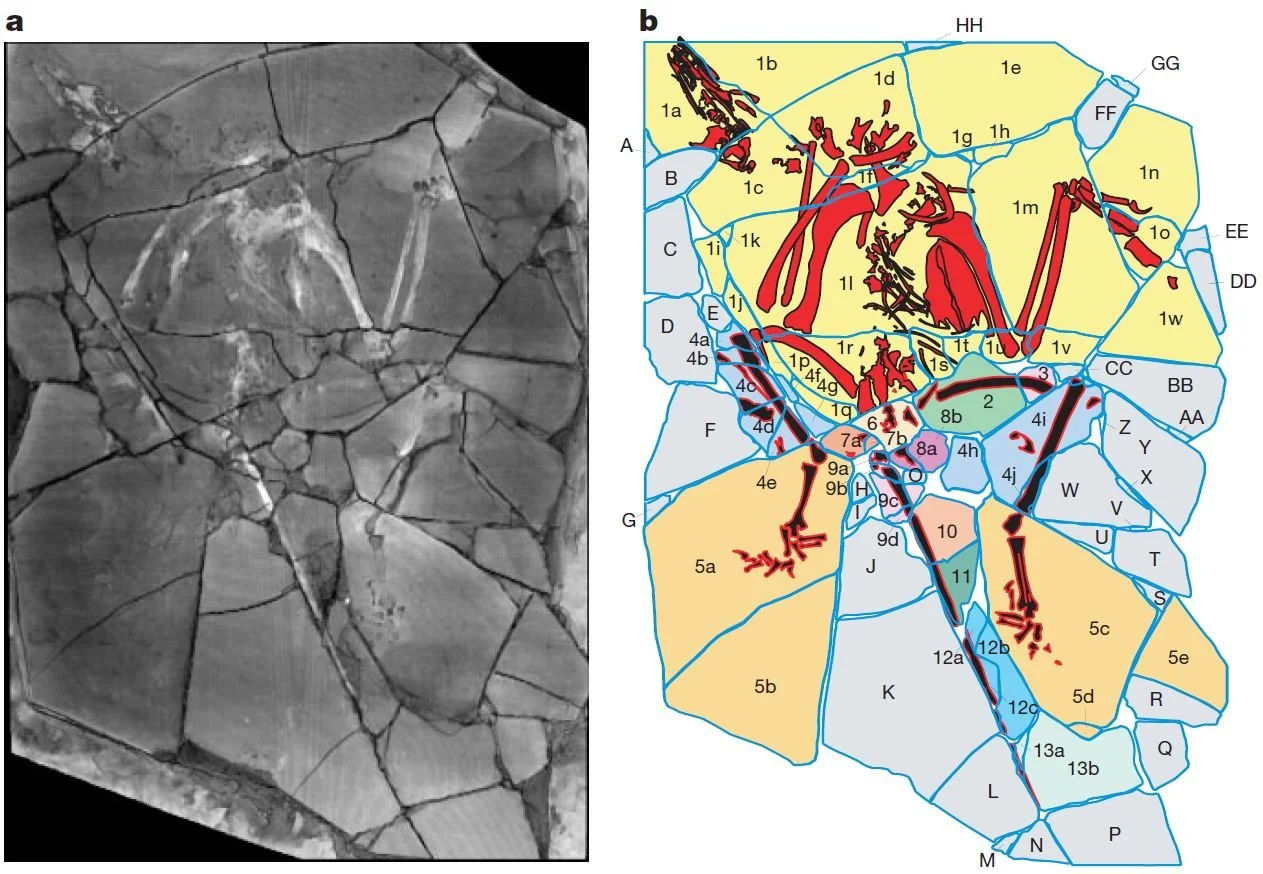

Caption: the ‘Archaeoraptor’ specimen – outed in the popular media (National Geographic magazine) as important in our developing ideas on bird-dinosaur evolution – proved to be a composite, or a hoax if you want, as demonstrated by Rowe et al. (2001). What specific relevance does this embarrassing mistake have for studies on archaic birds and allied dinosaurs at large? Well, none, and the only people who might return to it as some sort of faux dog whistle are creationists. Oh, and Alan Feduccia. Image: Rowe et al. (2001).

The repetition that Feduccia uses is especially telling. If you want someone to accept something that’s (at best) arguable and (at worst) wrong, keep repeating it in the hopes that they’ll accept it. Feduccia desperately wants readers to accept that the ‘plumed’ Triassic Longisquama had aerial capabilities and is relevant to avian origins, so every mention of it in RTBAD works in the idea that it was a ‘parachutist’. We even get “… the Triassic arboreal parachutist Longisquama, a small arboreal archosaur parachutist…” (p. 87). The hypothesis that Longisquama might have used its plumes in gliding is interesting, but that’s not the same as saying that it’s well supported… by which I mean that it’s not supported at all.

Caption: Longisquama (at left) and the drepanosaurids (like the two animals shown at right) are small, quadrupedal, climbing Triassic diapsid reptiles. They aren’t archosaurs or close kin of archosaurs, and there’s no good reason to think that they’re relevant to the ancestry of birds. Feduccia and his colleagues have repeatedly emphasized the possibility that these animals are closer to birds than are (non-bird) theropod dinosaurs. Image: Darren Naish.

Feduccia and the sauropod neck pose debate. Arguably the most insightful chapter in the book is that on neck posture in sauropods, and by ‘insightful’ I mean with respect to Feduccia’s vision of vertebrate palaeontology, not the debate in question. Two teams of specialists disagree on sauropod neck pose. Team 1 used digital modelling to argue that sauropods were constrained to semi-horizontal neck poses and that neck mobility was relatively restricted due to the nature of the overlapping facets between the vertebrae. Team 2 argued that x-ray data from living animals indicates that elevated neck poses should be assumed, that experimental evidence demonstrates that the overlapping facets allowed more mobility than was assumed by Team 1’s digital models, and that Team 1’s digital modelling has created an impression of certitude about neck anatomy that’s not supported by the specimens (all of which are deformed). Disclosure: I’m a member of Team 2.

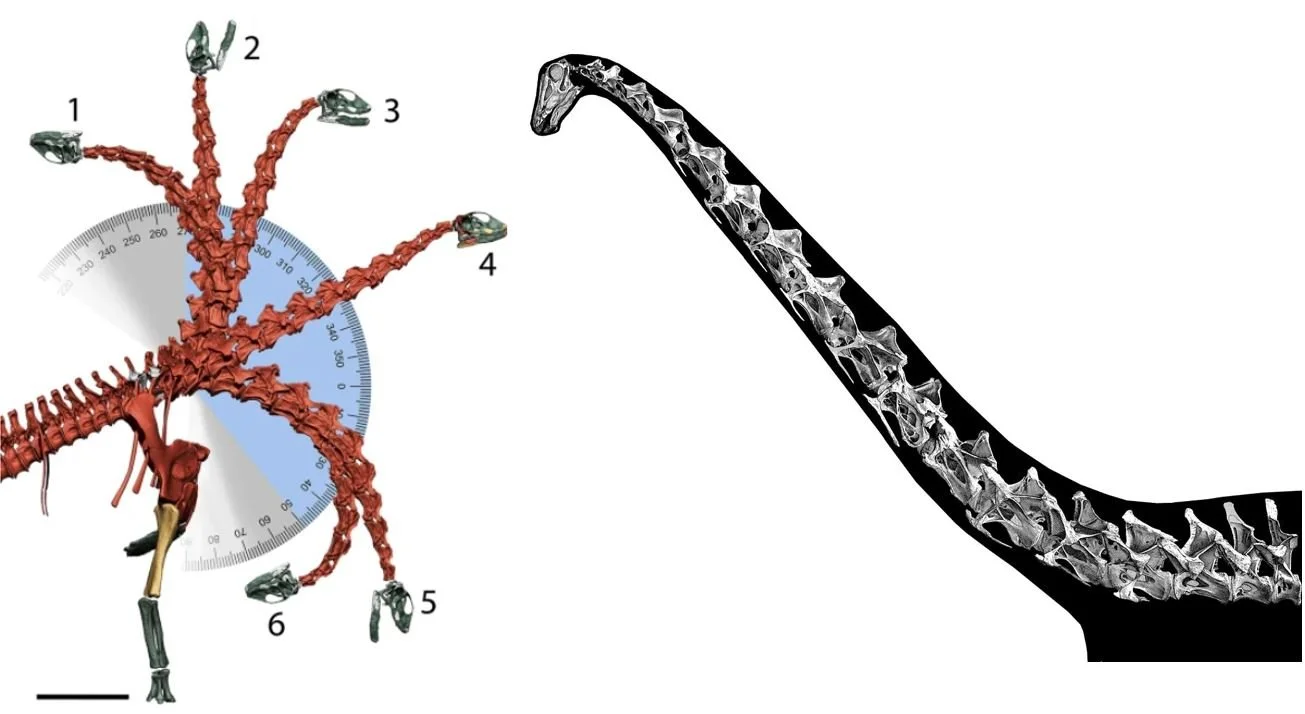

Caption: Taylor et al. (2009) argued that data from living tetrapods – including amphibians, mammals, squamates, crocodylians and birds – show how an elevated neck posture should be assumed as the default for extinct members of the group, in the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary.

Feduccia expresses strong preference for Team 1’s position and is dismissive of Team 2’s, labelling the authors “antagonists” (p. 37). Is this because he knows of methodological reasons why Team 2’s arguments should be dismissed? No, it’s because he argues that Team 2’s conclusions are based on emotional attachment to artwork in which sauropods were depicted as swan-necked (pp. 32-33). In discussing Team 2’s position, Feduccia only cites one of the relevant papers (Taylor et al. 2009) and incorrectly dismisses the data it contains as if it comes only from domestic mammals. He also points out that sauropods wouldn’t have been swan-like in neck flexibility, but no-one promotes that anyway. It’s strawmanning.

Why is this example ‘insightful’? Feduccia appears to regard the argument for semi-horizontal neck poses as the conservative, biologically more sensible view. But arguments over matters like sauropod neck pose are complex, and numerous authors have applied different approaches to this issue. To imply that a given view on the subject can be framed as reactionary, promoted for aesthetic preference, and favoured because it’s radical is dishonest and Feduccia is, again, guilty of using strawmanning and personal incredulity as his primary weapons.

Caption: Feduccia’s discussion of sauropods would have the reader believe that the ‘erect neck’ hypothesis is poorly founded, and promoted by radicals aiming to upset a more conventional view. It’s interesting that Feduccia does such a bad job of discussing the work that’s actually been published on this topic. The image at left shows postulated neck mobility in Spinophorosaurus, from Vidal et al. (2020a). The image at right shows Diplodocus in the habitual neck pose inferred by Taylor et al. (2009) on the basis of data from living tetrapods.

Of interest is that a lot has happened since Team 1 and Team 2 published their opening volleys. Studies of stress dissipation (Christian & Dzemski 2011), orientation of the vertebral column as a whole (Vidal et al. 2020a) and comparative studies between giraffe and sauropod ranges of vertebral motion (Vidal et al. 2020b) have been published. They conclude that sauropods held their necks in elevated poses. Feduccia doesn’t cite or mention any of this work of course, which is in line with his habit of ignoring evidence that contradicts the positions he prefers.

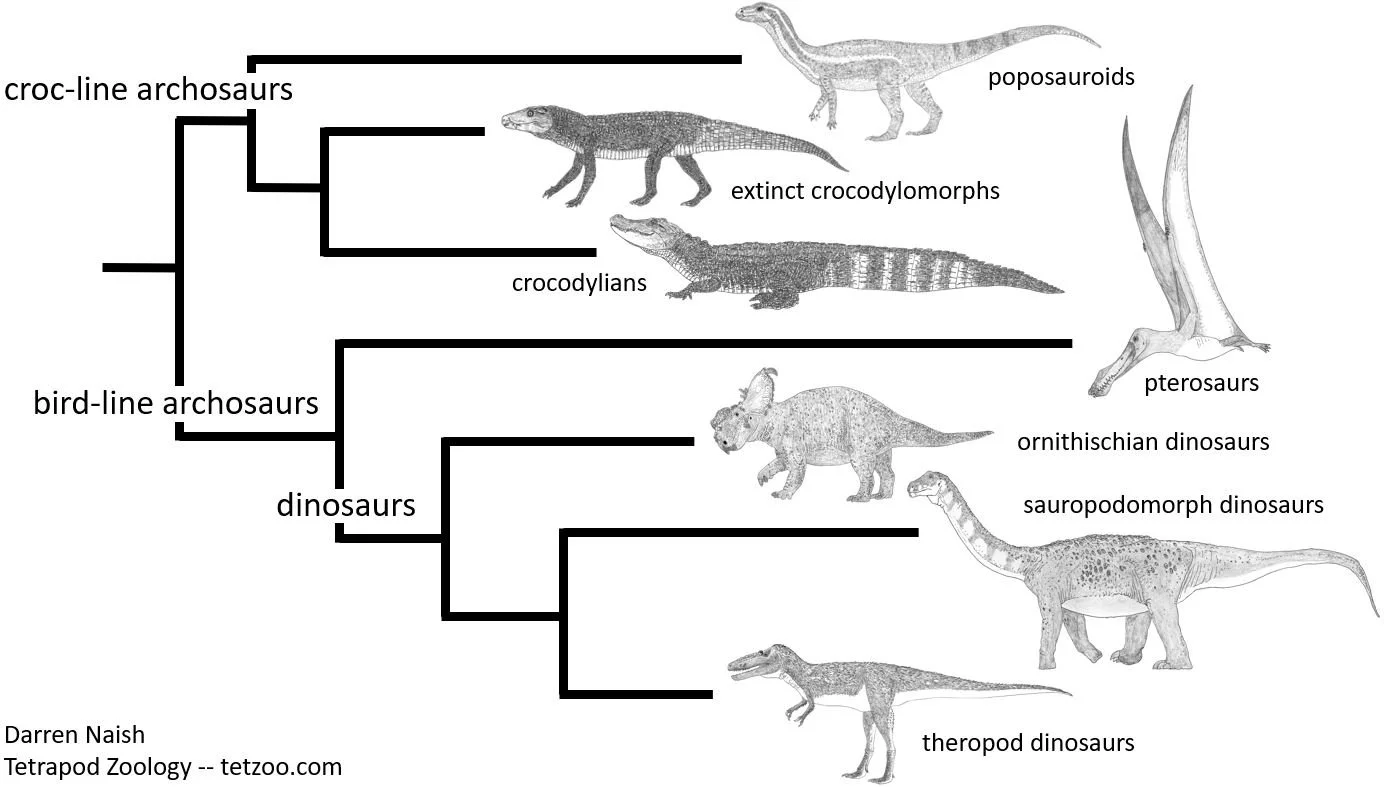

Feduccia and phylogenetics. Intellectual dishonesty or naïve falsification (or both) are at play where Feduccia discusses archosaur phylogeny, his aim being to show that the entire field is chaotic and uncertain, and that groups are artificial and poorly defined. Chapter 7 (‘Dinosaur: What’s That?’) opens with an anecdote whereby Feduccia asked an unnamed colleague to define Theropoda. Said unnamed colleague stated that “It’s whatever they say it is!” (p. 93); Feduccia goes on to note that Dinosauria is diagnosed by “hardly any morphological features other than large size and gait” (p. 94) and that those characters used to define Theropoda might be the consequence of convergent evolution to bipedality. After all, he states, we know that certain non-dinosaurian archosaurs of the Triassic were superficially theropod-like. He notes in passing that certain theropod characters are not present in all theropods, the implication being that this is a problem. This is either naïve or another dirty trick, since the phenomenon termed evolution means that not all members of a group have features present in the group’s early members.

Caption: a highly simplified depiction of archosaur phylogeny as we currently understand it. A number of superficially dinosaur-like members of the ‘crocodile line’ within Archosauria are known (like the poposauroid Effigia, shown here at the top of the diagram) and a substantial amount of anatomical data shows that they are indeed part of the croc-line clade, not the bird-line clade. The hypothesis shown here is based on a substantial number of studies that cite and discuss an enormous number of anatomical observations and discoveries. Image: Darren Naish.

A philosophical problem that Feduccia keeps bumping into here is his insistence that group membership within phylogenetics should be demonstrated by a few obvious anatomical traits. But animals are complicated objects, and if phylogenetics has taught us anything it’s that substantial amounts of data need to be analyzed if we want to recover something approaching ‘true’ phylogeny. The quest for two or three ‘key characters’ is a forlorn prospect, and pointing to a superficially dinosaur-like archosaur as if its possession of a deep snout and pointy teeth are enough to make it a dinosaur is woefully naïve given the tens of anatomical details that place it elsewhere in the archosaur tree.

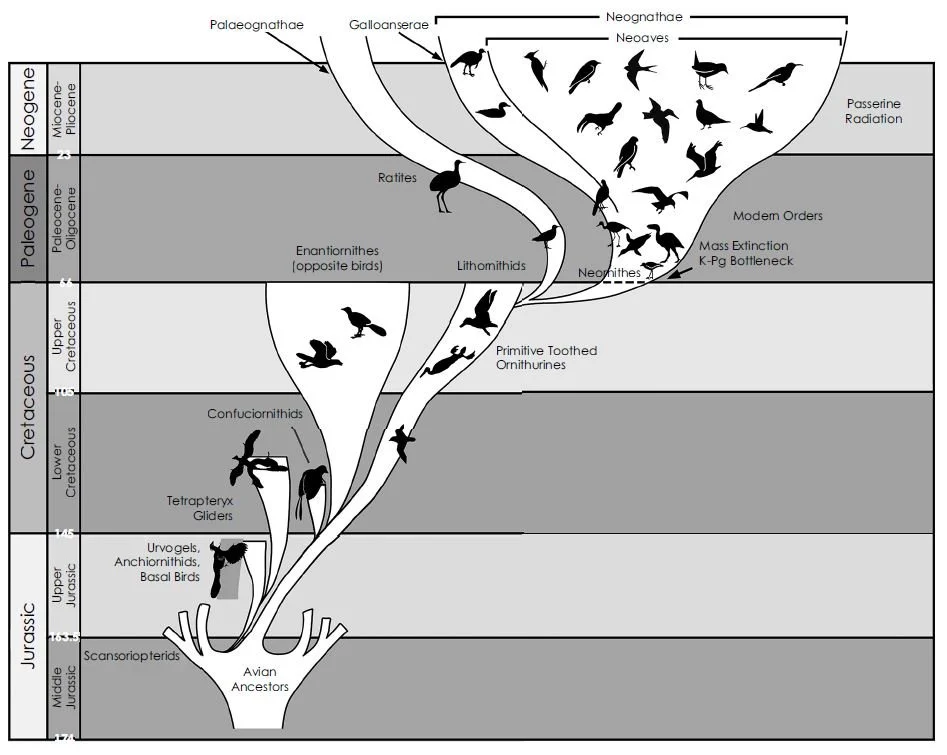

Feduccia and neornithine birds. We move now to Feduccia’s content on the evolution of neornithine birds, an area that those critical of Feduccia have tended to avoid. Feduccia tries to score points in RTBAD by arguing that modern findings justify his proposal of a post-Cretaceous ‘big bang’ in neornithine evolution, the implication being that this model was, and remains, smart and innovative. I don’t understand. Feduccia may well be right that neornithines did not originate as deep in the Cretaceous as some workers have argued, but that view is hardly novel to him. Furthermore, evidence does show that the bulk of the neornithine radiation occurred just after the end-Cretaceous event: again, this is a consensus view, not one that we only accept because of his work.

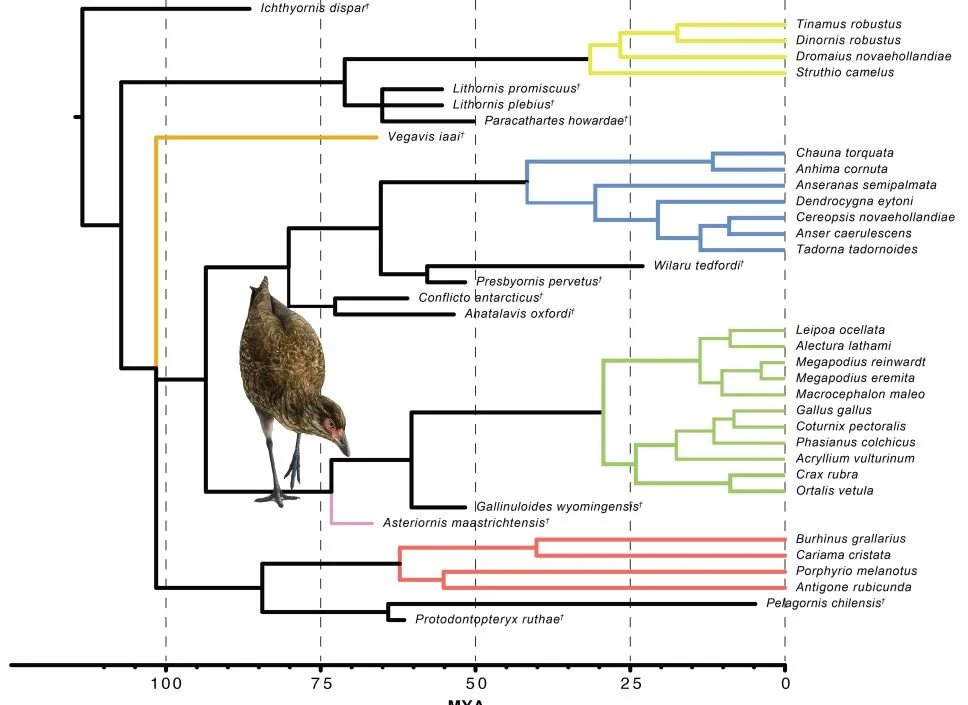

Caption: today, both the fossil record and time-calibrated molecular phylogenies converge on a similar answer…. neornithine birds originated during the Late Cretaceous but not right at its end. This cladogram from Field et al. (2020) shows how the main neornithine clades had perhaps diverged by 100 million years ago. It’s still the case that the vast bulk of neornithine lineages originated after the Cretaceous, however. Image: Field et al. (2020).

However, evidence (example: the recently described galloanserine Asteriornis) shows that this radiation was well underway long prior to the very end of the Cretaceous, the latest work showing that the main neornithine clades (palaeognaths, galloanserines and neoavians) had diverged somewhere between 100 and 75 million years ago (e.g., Field et al. 2020). Feduccia’s own diagrams show a Late Cretaceous origination for neornithines (Feduccia 2020, p. 297), yet he contests the existence of Late Cretaceous neornithines throughout his text. It’s a confusing picture and I find it dishonest that Feduccia claims to have introduced something valuable.

Caption: the version of the neornithine ‘big bang’ portrayed in RTBAD. This version differs from ones that Feduccia has published before in that they show the neornithine radiation originating in the Late Cretaceous. Image: Feduccia (2020).

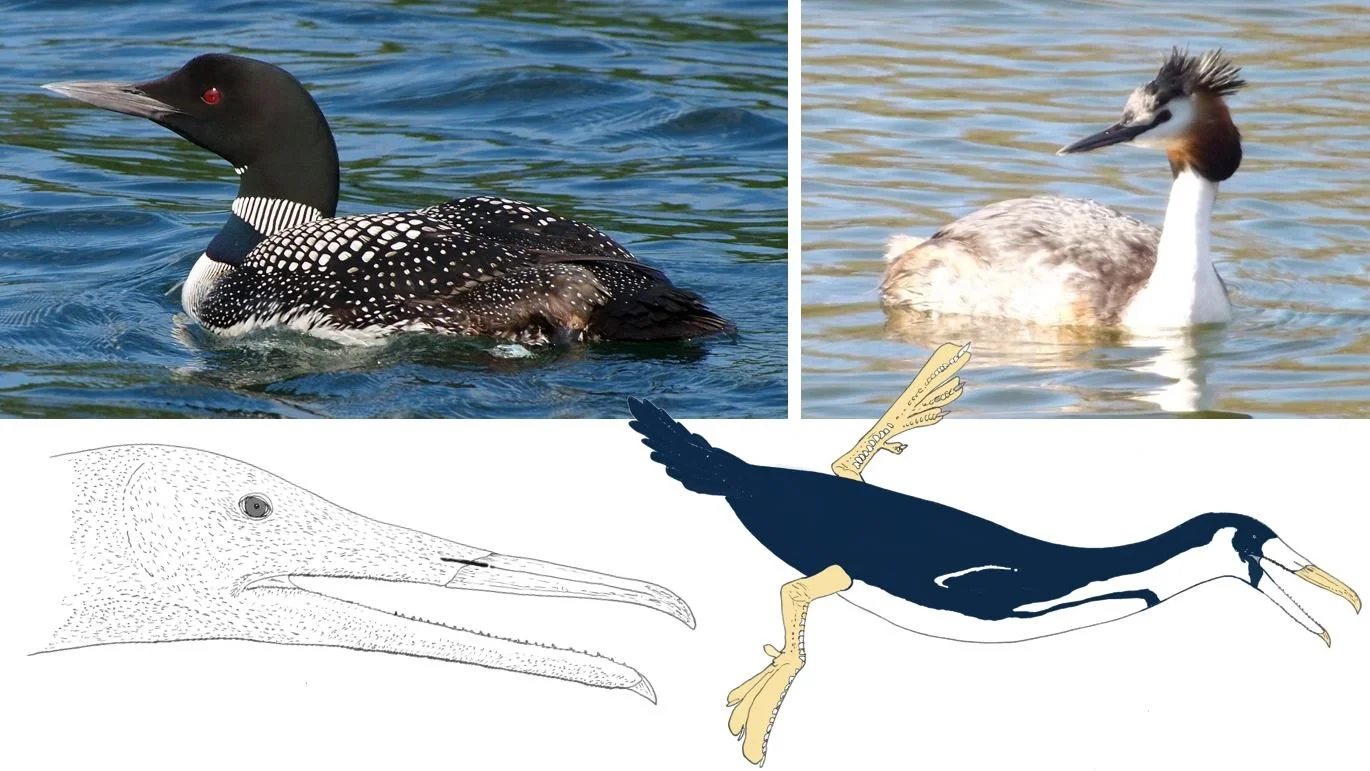

In an additional example of strawmanning, Feduccia attempts to diminish efforts to use phylogenetic systematics by saying that the recovery of a grebe-loon clade demonstrates how such efforts are doomed to failure. Yet again: yes, people make mistakes in science, and the claimed recovery of a grebe-loon clade can be put down to the inclusion of insufficient data. It’s unfair to use this as some kind of excuse to throw up your hands and stop doing science. And, hey, it’s not as if more qualitative efforts to determine the relationships between organisms are somehow superior, as is demonstrated by the wrong phylogenetic hypotheses endorsed aplenty in Feduccia’s own research (Feduccia 1977a, b, 1978, Feduccia & Olson 1980a, b).

Caption: it’s true, Joel Cracraft once argued that divers/loons (upper left), grebes (upper right) and hesperornithines (below) were close kin within a group termed Gaviomorphae. Other authors have found a diver + grebe clade more recently. Is this proof that efforts to determine avian phylogeny via cladistics are a waste of time, doomed to failure? No, it’s proof that scientists sometimes get things wrong. Images: diver by John Picken, CC BY 2.0 (original here); others by Darren Naish.

In similar vein, Feduccia attempts to mislead the reader by reeling off a list of phylogenetic hypotheses no longer regarded as correct. The examples he uses include the once-popular linking of whales with mesonychians, the suggested placing of dromornithids within ratites, and a proposed affinity between stiff-tailed ducks and the big, unusual, musk ducks. Feduccia’s point here is that phylogenetics as practiced by cladists is fatally flawed. But – again – that’s not what these examples show. They show that phylogeneticists make mistakes by failing to incorporate relevant data or, even better, data that was unknown when the hypothesis in question was proposed. This is hardly a fatal flaw but an inevitable consequence of progress.

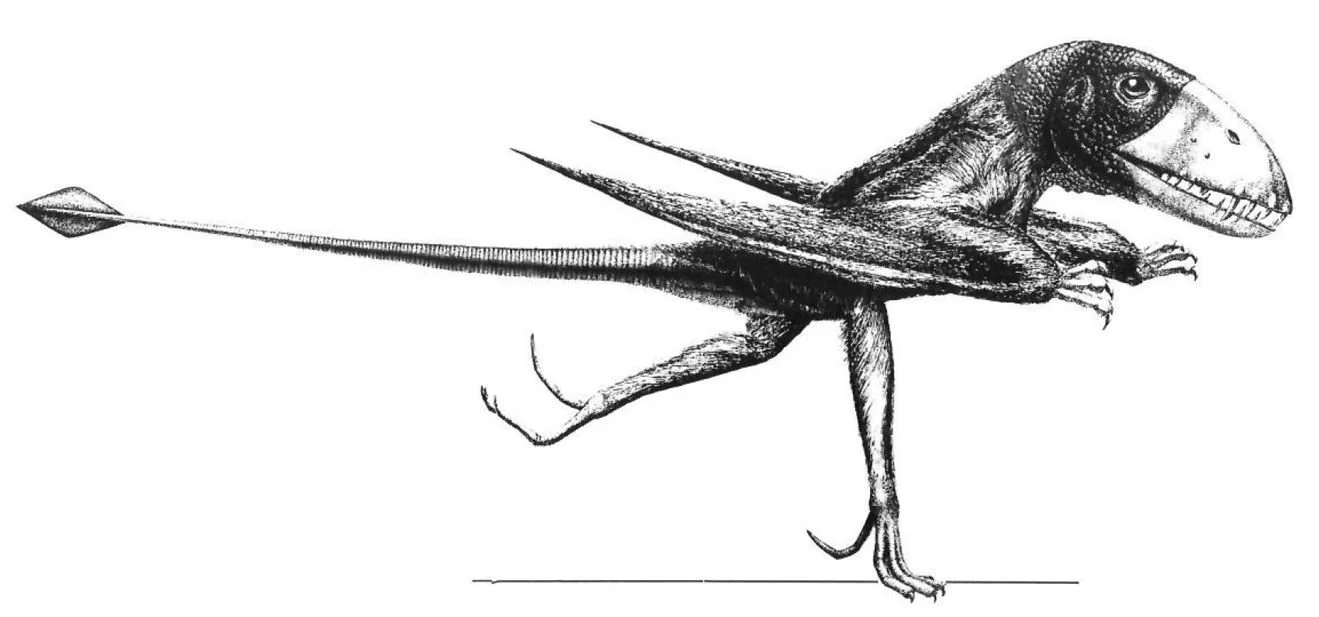

Feduccia also includes here a claim that pterosaurs were once regarded as a sister-group of theropods. No: the claim was that pterosaurs are close kin of dinosaurs, something that still appears to be the case. Feduccia mixes this up with the claim that pterosaurs were regarded as “obligatorily bipedal” and took to flight from the ground up. While connected to the argument that pterosaurs are close kin of dinosaurs, this was presented as an argument from functional anatomy, and it’s out of place in a list of contested phylogenetic hypotheses.

Caption: an iconic image of the Jurassic pterosaur Dimorphodon, by J. Kevin Ramos, used in several of Kevin Padian’s papers and articles published during the 1980s. Feduccia is fixated on this work, since he’s frequently drawn attention to this specific view of pterosaurs (which is not endorsed by anyone other than Padian). Image: J. Kevin Ramos.

Yet another strawman is set up in Feduccia’s claim that ornithologists widely and uncritically accept the old-fashioned view that ratites owe their distribution to vicariance. This view was promoted during the 1980s by Joel Cracraft, and – yes – it’s been promoted by science writers (Feduccia quotes Richard Dawkins). But is it accepted today? A substantial amount of work has replaced it, and it’s misleading to argue that it has sway now.

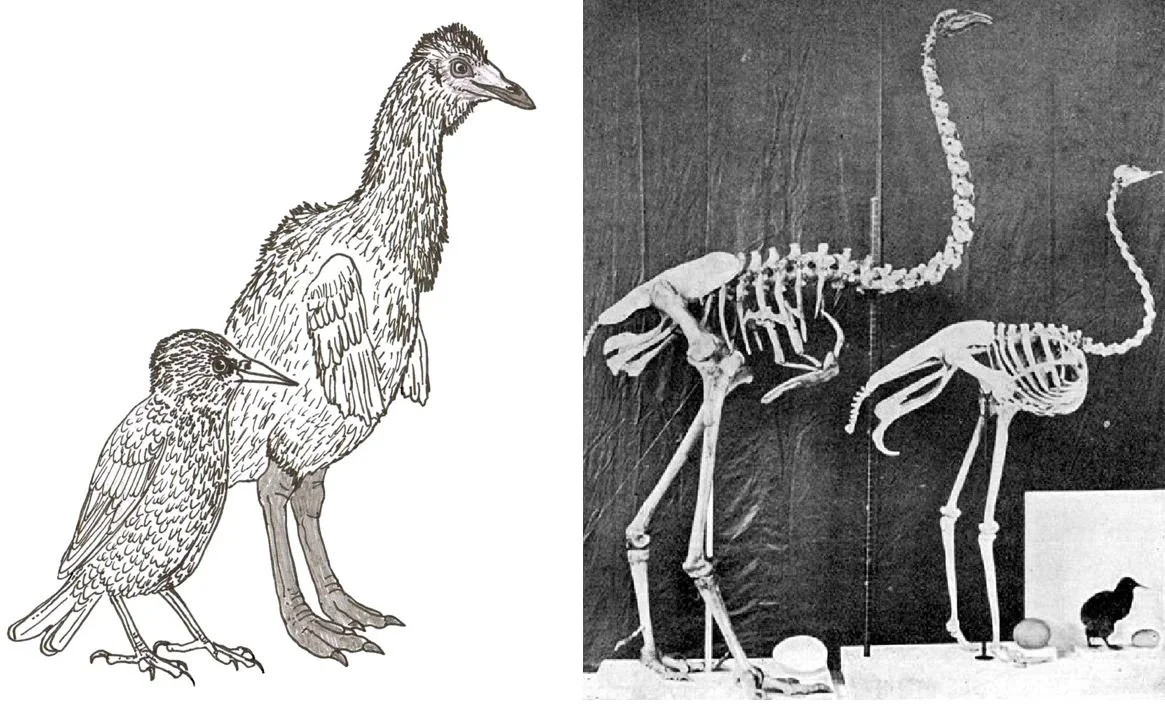

Also on ratites and kin, Feduccia once again promotes the view that these birds owe their anatomy to paedomorphosis. This is a historically popular hypothesis, to be sure, but it has a lot counting against it and may be wrong: see the Tetrapod Zoology article Controversies in Ratite and Tinamou Evolution (Part I). You wouldn’t know this from Feduccia’s perspective, since he presents an entrenched position that a paedomorphic explanation for ratite morphology is so self-evident that it shouldn’t be challenged. Time and time again, Feduccia’s coverage of an issue comes across as misleading and misrepresentative of the position favoured by those working in the field.

Caption: the hypothesis that ratites are paedomorphic has been popular. We don’t know that it’s true; it’s a hypothesis, and not one that matches the data all that well. Images: Darren Naish; public domain.

That never-ending debate on avian digit homology. Over recent years, Feduccia has devoted time to the homology of the avian hand, his argument being that avian and theropod digital complements are different, and – ergo – birds can’t be theropods. He argues that his work was done “to shed light” (p. 138) on the issue. I’m cynical. I think that it was specifically pursued in an effort to erode the bird-dinosaur link (you’ll recall the comment about targeted confirmation bias). Claims that identification of avian hand digits as I-II-III “accommodate the cladogram” (p. 142) are not fair; the suggested pattern is based on homology observed across phylogeny, and this exists whether one uses cladograms or not.

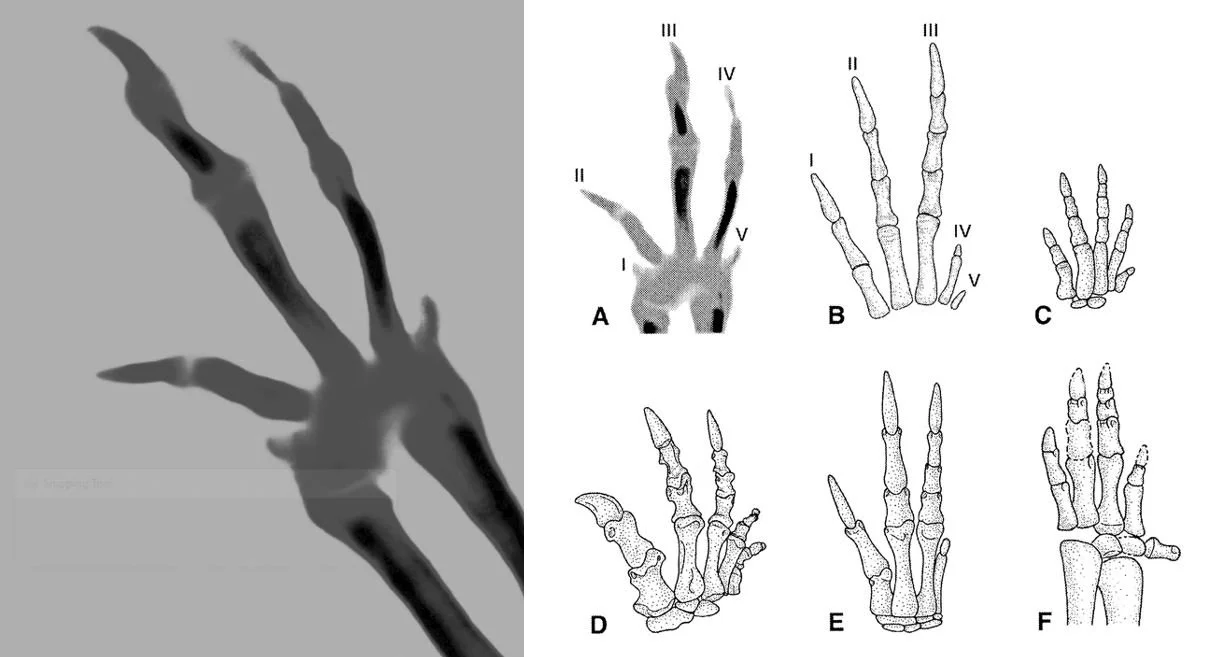

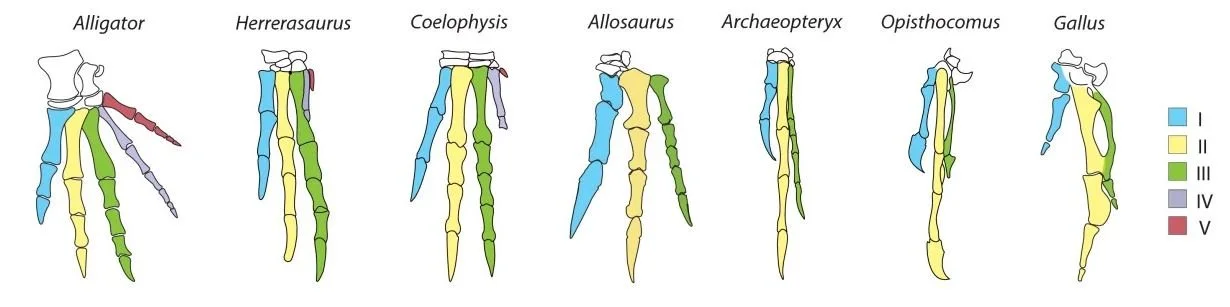

Caption: at left, ostrich embryo right hand in dorsal view. At right, the same hand (A) compared to that of (B-F) non-bird dinosaurs. Integral to Feduccia’s identification of digits in the avian hand is the argument that ostrich embryos are pentadactyl, with those little spurs at the base being digits I and V. But is that so? Vargas & Fallon (2005, pp. 241-215) noted that these “condensations of the wing appear at a much later stage than the digital condensations of the functional digits, are very small sized, and only transiently detectable. Therefore, these mesenchymal condensations cannot be compared with much certainty to specific digits that were lost in the adult”. Feduccia (2020, p. 151) quotes the following from Henry Gee: “I can’t make much of this image; it reminds me of a Rorschach Test”. Images: left, Feduccia (2020); right, Feduccia (2002).

Any effort to understand what consensus might exist on the development of the avian hand will reveal that different, distinct models have recently been considered, and – importantly, given Feduccia’s bias – that even those finding a II-III-IV configuration (e.g., Čapek et al. 2013, de Bakker et al. 2021) are not deemed inconsistent by their authors with theropod ancestry. Some studies on gene expression show Hox genes supporting the I-II-III pattern (Vargas & Fallon 2005, Salinas-Saavedra et al. 2014), though not all do (Stewart et al. 2019, de Bakker et al. 2021). It is, nevertheless, amusing to see Feduccia bend over backwards to explain the genetic studies away, noting that “[just] because something can be shown experimentally does not mean it happened in nature” (p. 144).

In an effort to reconcile an avian II-III-IV pattern with the I-II-III generally thought correct for tridactyl theropods, some authors have proposed a ‘frame shift’: an event where the pattern of digit formation ‘shifted’ to a different location in the hand (embryonic hand formation is supposed to start with digit IV). Feduccia is dismissive, asking “what’s the point?” (p. 144), later arguing that a frame shift is nonsensical since it wouldn’t serve any function. It should be obvious why the frame shift hypothesis is worth considering, since it provides a potential explanation for otherwise surprising results. While Feduccia might be more interested in birds than other theropods, the fact is that non-bird theropods have remarkable hands too, the presence of didactyl and even monodactyl lineages meaning that we might well be talking about frame shifts within theropod manual evolution even if birds didn’t exist.

Caption: based on the pattern of hand anatomy as seen across evolutionary history, it looks obvious that the bird hand is formed of digits I, II and III. However, looks can be deceiving… what does molecular data say? By looking at the expression of HoxD genes in the developing hand, some studies report molecular support for the I-II-III configuration. Image: Salinas-Saavedra et al. (2014).

As for ‘function’, we don’t know why these events occur. The fact that they’ve been reported for the hands of certain salamanders and skinks (Feduccia implies that they’re unknown outside the proposed theropod/bird example) is no more significant for the function and structure of these animals than it theoretically is for birds and other theropods.

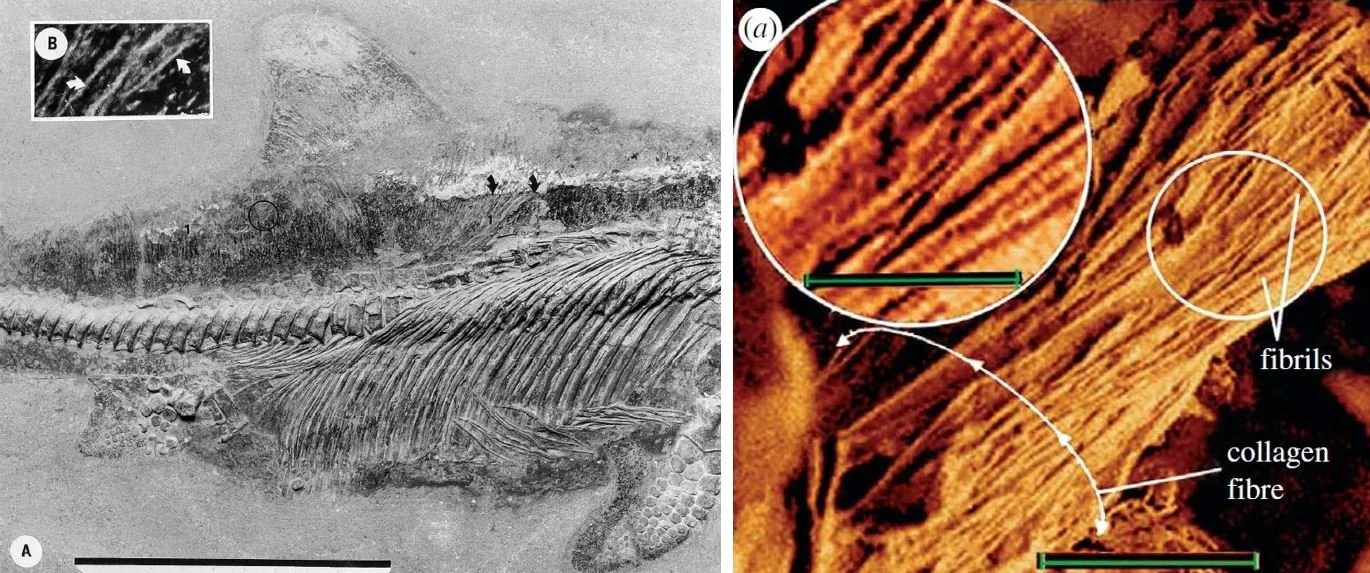

The ‘collagen model’ for dinofuzz: bad science, not good. Another debate in which Feduccia seemingly holds a fixed, contrarian position is that concerning the integumentary filaments known from various dinosaur and pterosaur fossils. Feduccia tries hard to make the reader believe that these have been debunked as collagen fibres. This hypothesis was proposed early in the modern wave of (mostly Chinese) dinosaur and pterosaur finds and it’s hard to escape the inference that Feduccia wants these filaments to be collagenous because, again, it helps derail the idea that dinosaurs and pterosaurs might have been bird-like.

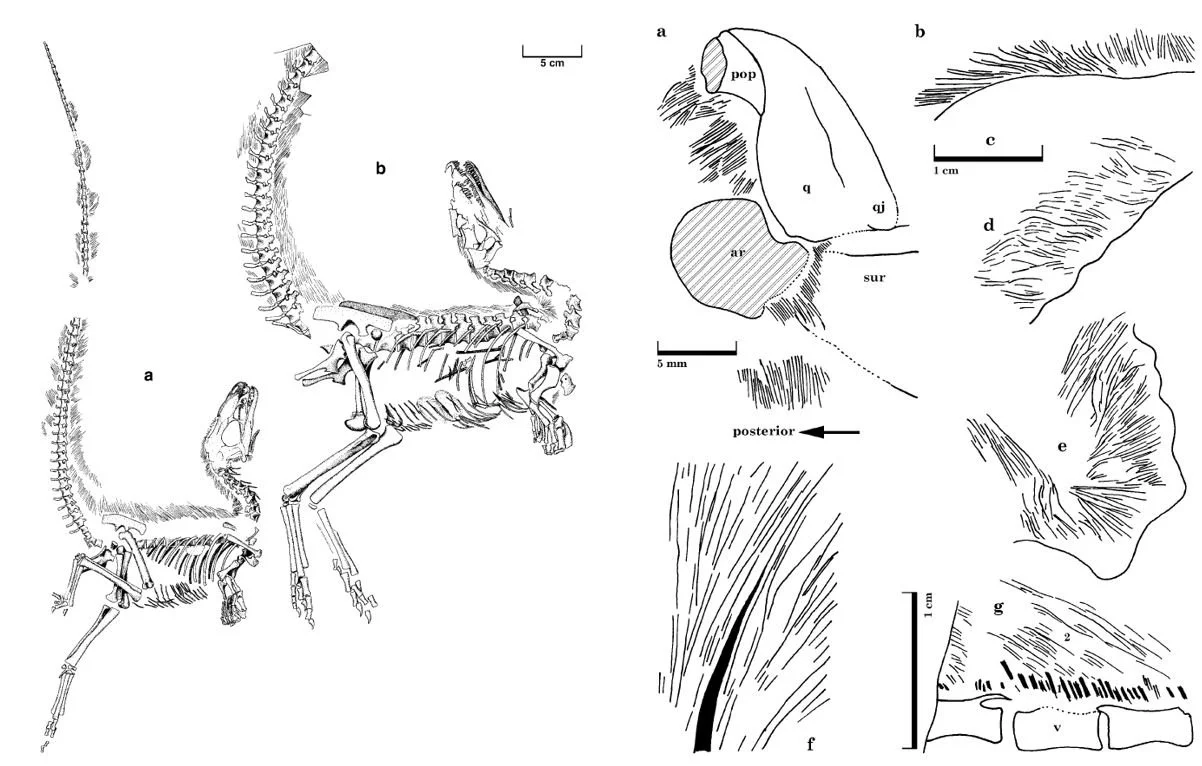

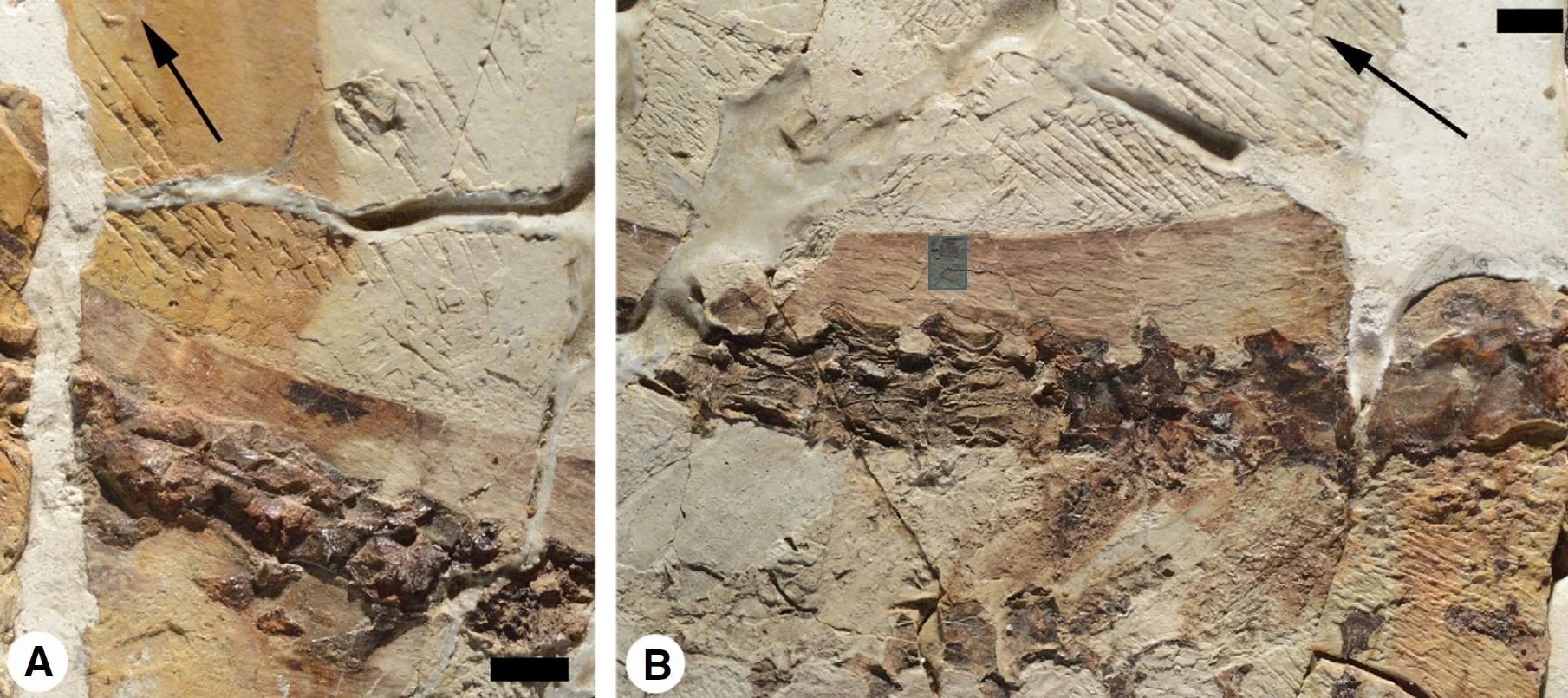

Caption: an opinion promoted by some in the discussion on bird origins is that being highly sceptical of dinosaur ‘fuzz’ represents a good, honest stance. And scepticism on this issue is, obviously, not ‘bad’. But immediately casting aspersions (which is what Feduccia did: Morell 1997, p. 38) was and is a sign of massive bias. These images (from Currie & Chen 2001) show two of the Sinosauropteryx specimens that exhibit integumentary filaments ((a) NIGP 127586 and (b) NIGP 127587), plus close-ups of the filaments preserved across their bodies (and not just on their dorsal midlines, as Feduccia and colleagues have stated). Images: Currie & Chen (2001).

Feduccia’s inference in RTBAD is that good, solid science has demonstrated a collagenous identification for the filaments. Even the most generous evaluation reveals that this is inaccurate. At best, it’s a hypothesis. “Why have paleontologists refused to consider the possibility that these filaments represent collagen fibres?” (p. 184), Feduccia asks. Because the two don’t look alike, because dinosaur filaments possess features showing that they’re keratinous, not collagenous, and because those aiming to convince others that the filaments are collagenous have either screwed up or pushed really hard – cheated, you might say – in their efforts to make collagen fibres resemble dinosaur filaments. I say ‘cheated’ because Feduccia figures anatomical preparations where collagen fibres have been teased out of bone in an effort to create objects that look like filaments. You’d be justified in asking what relevance a laboratory preparation has for fossils of fuzzy-coated dinosaurs and pterosaurs. After all, “[just] because something can be shown experimentally does not mean it happened in nature” (p. 144).

Caption: integral to Feduccia’s argument that filaments on Sinosauropteryx are collagen fibres is the interpretation of said filaments as “beneath the skin outline” (p. 185), internal to the “clearly demarcated body outline” (p. 165). In the Sinosauropteryx specimen (IVPP V12415) you see here (this image shows part of its tail), said ‘skin outline’ or ‘body outline’ is marked with red arrows. It’s no ‘outline’, but the demarcation between an area where the matrix has been broken off by preparation tools versus that where the matrix remains. This is the case for all the specimens concerned. Most observations used to support the collagen fibre hypothesis are of this calibre. Image: Darren Naish.

Feduccia also figures slender, multi-branched ligaments carefully extracted from modern birds and tidily photographed to show how similar they are to dinosaurian and pterosaurian filaments. Superficially similar in external appearance they might be, but where do ligaments occur? Do they project in pelage-like orientation from the outside of the body, as they do in the relevant dinosaurs and pterosaurs? No, they are unique to specific regions, like the digits and neural spines.

The only worker beside Feduccia who has properly argued for the collagenous interpretation is the late Theagarten Lingham-Soliar. Lingham-Soliar is discussed on numerous occasions throughout RTBAD, mostly because he was Feduccia’s only supporter on the issues at hand. A brief digression on Lingham-Soliar – Solly to his friends and correspondents (of which I was one) – is worthwhile.

Caption: at left, one of Lingham-Soliar’s ichthyosaur skin fibre images, showing the fibres very much internal to the external body outline and thus deeply embedded within the skin. At right, a close-up of ichthyosaur skin fibres as provided by Lingham-Soliar & Wesley-Smith (2008). Note that the numerous tiny fibrils do not taper toward their ends and are united in thick, rope-like structures. They don’t resemble dinosaur filaments in detail. Images: left, from Lingham-Soliar (2001), scale bar = 10 cm; right, Lingham-Soliar & Wesley-Smith (2008), scale bars = 2 microns, 1 micron in insets.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, Lingham-Soliar published papers on the skin of ichthyosaurs, his primary interest being their complex, multi-layered networks of collagen. These are embedded within the skin and consist of overlapping, grid-like fibre arrays. They don’t look like the integumentary filaments of dinosaurs and pterosaurs. Alas, Lingham-Soliar did not hold this view himself, and between 2007 and 2015 published papers and books in which, like Feduccia, he aimed to show that the filaments on dinosaurs are misidentified collagen fibres. I’ve often wondered if Lingham-Soliar only began considering ichthyosaur collagen fibres relevant to the dinosaurian and pterosaurian data after being approached on this matter by Feduccia.

Outside of Feduccia’s writings, how were Lingham-Soliar’s arguments received? The primary response was rejection, since better and more thorough tests on the dinosaur filaments found them to be non-collagenous, external, and possessing a microscopic anatomy unique to integumentary filaments (Mayr 2010, Zhang et al. 2010, Godefroit et al. 2014, 2020, Mayr et al. 2016, Smithwick et al. 2017). Some of the features integral to Lingham-Soliar’s argument – that is, that the filaments in dinosaurs like Sinosauropteryx are misinterpreted collagen fibres – are mistakes caused by the low magnification he was using, or are misidentified preparation marks or holes in the matrix. Feduccia avoids mentioning any of this, but in discussing Smithwick et al.’s (2017) rejection of Lingham-Soliar’s proposals, he write that their study is “not based on confirmable evidence” (p. 186). As per the Hox gene example noted above, that sure sounds like a way of dodging a conclusion you don’t like.

Caption: Lingham-Soliar argued that several long, straight, non-tapering ‘fibres’ surrounding the fossils of the theropod Sinosauropteryx can be identified as collagen fibres. The features he had in mind were preparation marks made by tools, like those shown here (from Smithwick et al. 2017). Scale bars = 10 mm. Images: Smithwick et al. (2017).

The bottom line on this whole issue is that the ‘collagen camp’ that Feduccia promotes is based on superficial similarity and assertion, and the taphonomic and microstructural work published so far does not support Feduccia’s claim that there is “collagen, collagen, everywhere!” (p. 190).

An immobile position on the flight origins debate. Feduccia’s chapter on WAIR (the ‘wing-assisted incline running’ model of flight origins) is yet another section packed with personal incredulity and strawmanning. Another of Feduccia’s immobile positions is that flight (and feathers, and birds) originated in the trees, ergo any model positing a ground-up origin can only be dismissed. WAIR – published by Ken Dial and colleagues in and around 2003 – enjoyed time in the limelight in providing a seemingly good explanation for how maniraptorans perhaps made their first forays into flight. Things began to become undone once it became clear how specialised for flight a bird has to be in order for WAIR to work, and today WAIR is not popular as an explanation for the beginnings of avian flight. Feduccia knows us better than we know ourselves though, and insists that WAIR is alive and well.

Feduccia also contends that models positing wings as providing propulsion from the ground “have come and gone” (p. 224), but that isn’t accurate either as such views have been incorporated into modern hypotheses of flight origins (Dececchi et al. 2016, Naish & Barrett 2018, Larsson et al. 2020). As for Feduccia’s statement that “no vertebrate has [evolved flight] from the ground up” (p. 225; his use of italics), maybe this explains why birds are so different from other volant vertebrate groups, all of which have hindlimbs incorporated into a wing membrane.

Caption: Dececchi et al. (2016) showed that at least some non-bird maniraptorans do not have the right combination of anatomical features to benefit from WAIR as originally envisioned. Image: Dececchi et al. (2016).

A position encountered throughout the book is that a given area of contention has been settled thanks to a new discovery or study: that science there is finished, always in the direction of Feduccia's preferred perspective. What Feduccia fails to note, or perhaps is unable to perceive, is that he’s guilty of promoting specific arguments and conclusions consistent with his preferred view as if they represent the ‘last word’ on the specific issue. This is tone-deaf given the view promoted elsewhere in the book (namely, that the relationships between archaic birds and bird-like maniraptorans are difficult to disentangle). One example comes from his criticism of work on the Romanian Balaur. Feduccia doesn’t like studies that regarded it as a dromaeosaurid but is happy with one (Cau et al. 2014) that shows it to be “little more than a secondarily flightless bird”. But the study concerned – I’m one of its authors – can’t be considered a ‘last word’ on this matter given the labile nature of Balaur in phylogenetic studies.

Caption: interpreted as a jeholornithid-grade member of Avialae, as per Cau et al. (2015), Balaur might have looked less ‘Velociraptor-like’ than depicted in some recontructions. But would it be fair to then describe it as “little more than a secondarily flightless bird”, as Feduccia suggests? Image: Jaime Headden, used with permission.

Physiology. Feduccia’s arguments about dinosaur physiology are also dishonest. The majority of scientists working on non-bird dinosaurs think that these animals had an ‘elevated metabolism’ of some sort. It’s likely that dinosaurs of most or all sorts were endothermic, but at least some work promotes mesothermy or heterothermy, and it could be that dinosaurs used diverse strategies. This is more in step with our understanding of living animals than a simple dichotomous view, since we know that heterothermy and even ectothermy is present in some mammals, that true endothermy has evolved in cartilaginous and ray-finned fishes, that partial endothermy is present in some lizards, and so on. It’s shades of grey, as are so many things in the world of biology.

Caption: modern big reptiles, like pythons and alligators, are not dinosaur-like at all. But a point made several times in Feduccia’s writings is that the existence of such animals is really very much relevant to the fact that there are (or were) non-bird dinosaurs. Images: Darren Naish.

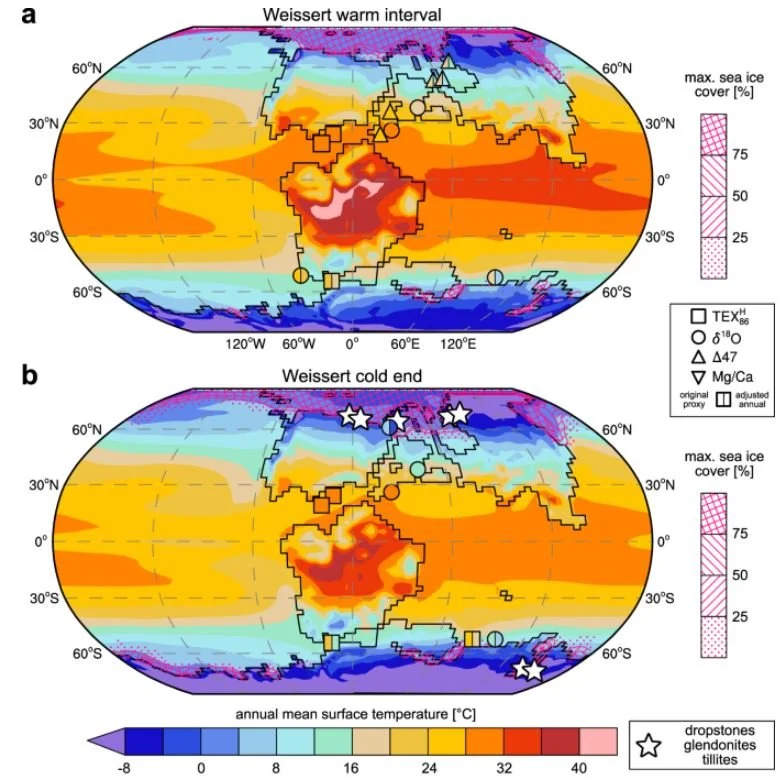

Feduccia argues that non-bird dinosaurs were assuredly ‘cold-blooded’, and he mentions several reasons for favouring this view. One is that pythons and alligators are capable of fantastic feats of behaviour despite their physiology, therefore dinosaurs. Another is that the Mesozoic was a perpetual global hothouse. He states this with lamentable regularity, describing the Cretaceous as “monotonously hot” numerous times. It’s true that long sections of the Mesozoic were very warm. But this was not true for the entirety of Mesozoic time: dinosaurs and their contemporaries were alive when conditions were temperate, cool or even cold (Cavalheiro et al. 2021, Wang et al. 2023). The Lower Cretaceous deposits of Liaoning Province – famous for their filamentous small theropods and pterosaurs, and numerous feathered non-bird maniraptorans and archaic birds – appear to have been deposited in cool, Alpine habitats, to take one example. He mentions ‘ectothermic growth rings’ as if they’re a slam-dunk for a non-endothermic physiology, despite the fact that the old black-white view on these structures is known to be wrong. In short, Feduccia’s entire chapter on physiology is rambling and chaotic, ending with what reads like a stream of consciousness on zoological miscellanea.

Caption: these global temperature maps for the Valanginian in the Early Cretaceous, from Cavalheiro et al. (2021), show projected temperatures of less than 12 degrees C across large areas of North America and Eurasia. Numerous dinosaur fossils are known from this timeframe, from the cool and cold areas. Note the sea ice projected for the polar regions too. Yes, there were long warm spells across the Mesozoic but we’re long past the time where the whole of the Mesozoic (or even whole of the Cretaceous) can be framed as a perpetual hothouse. Image: Cavalheiro et al. (2021).

For the love of Greg Paul. Some reasonable section of RTBAD is devoted to the idea that maniraptoran theropods are misidentified birds, and that these animals are not related to other theropods, instead representing a lineage that emerged from among ‘avimorph thecodonts’ of the Triassic. After arguing for decades that animals like Deinonychus, Velociraptor and Oviraptor do not have any important similarity to archaic birds, Feduccia is now of the opinion that these dinosaurs and their kin are part of the bird clade… but are somehow not dinosaurs.

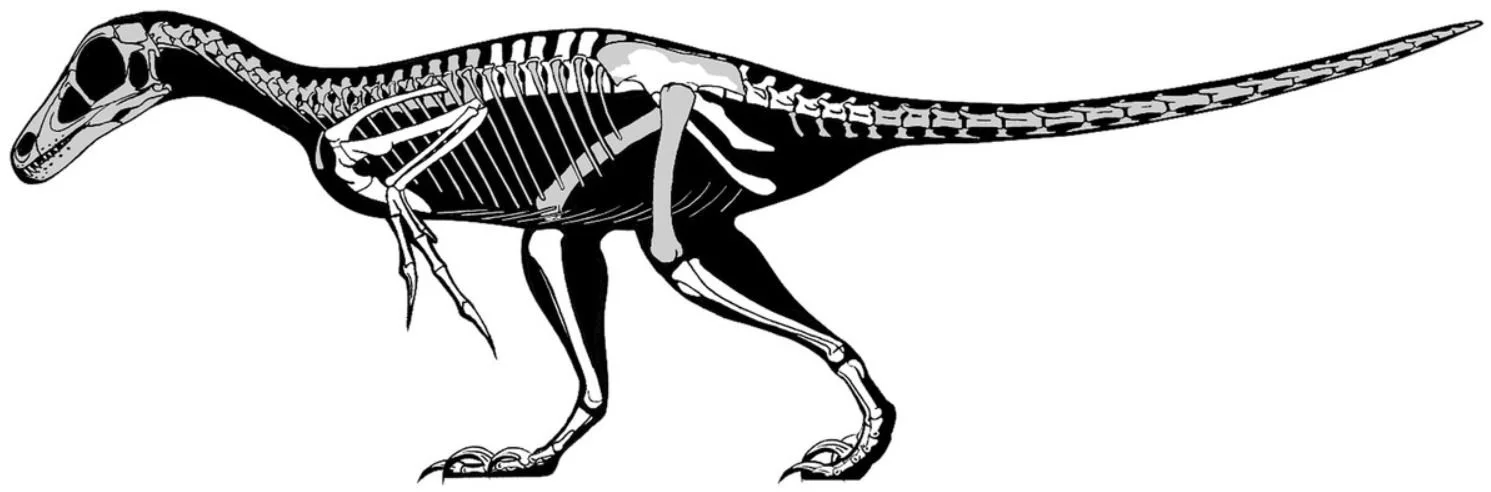

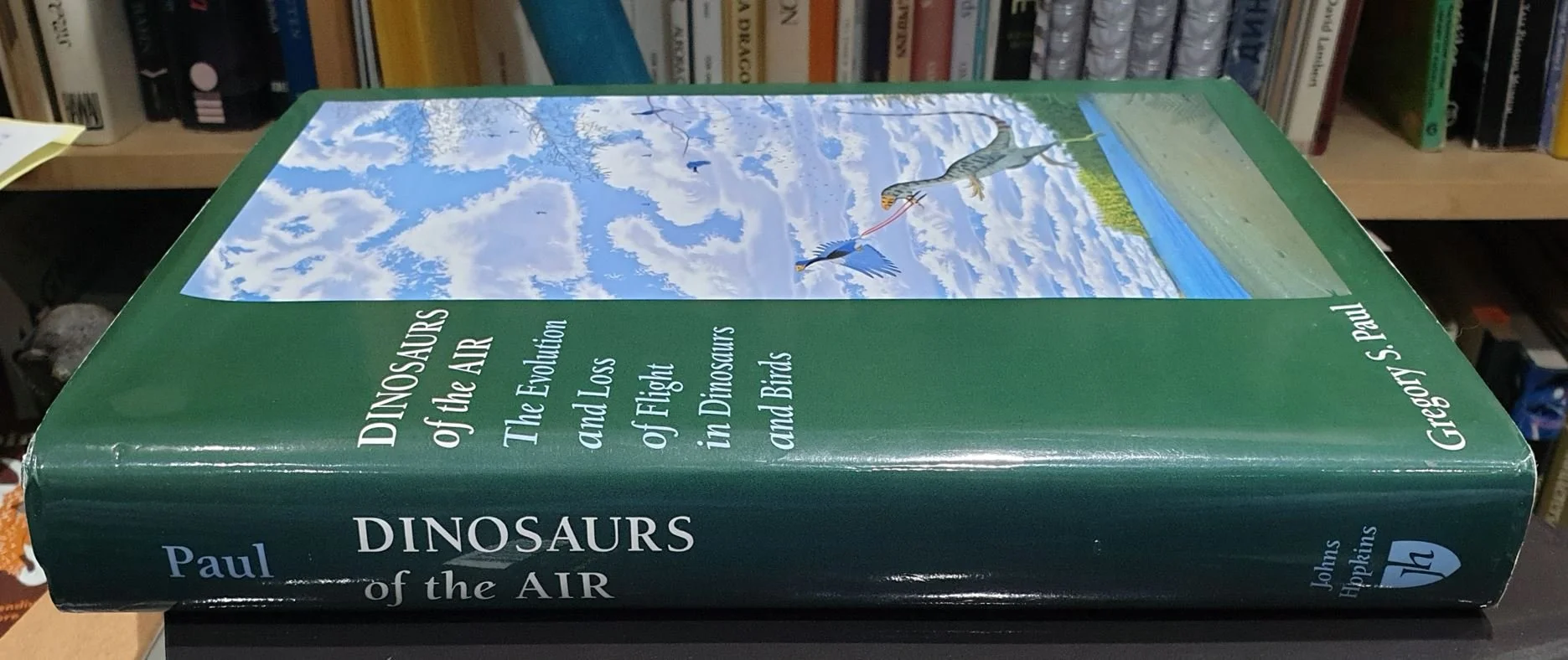

The notion that maniraptorans like Velociraptor might be the flightless descendants of Archaeopteryx-like forms is the brainchild of Greg Paul, who explained it most cogently in his 2002 Dinosaurs of the Air: the Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinosaurs and Birds. Combine the indisputable evidence for the existence of feathers on maniraptorans with Feduccia’s hardline insistence that feathers maketh the bird, and we have Feduccia cosying up to Paul and adopting a broken version of Paul’s ‘all maniraptorans are birds’ hypothesis (broken, because Paul, unlike Feduccia, still regards maniraptorans as coelurosaurian theropods). That’s amusing given the utter disdain Feduccia has expressed for Paul in the past.

Caption: the late Larry Martin was first to use the term ‘Paulian School of Bird Origins’ to describe endorsement of Paul’s ‘neoflightless’ hypothesis. RTBAD confirms Feduccia’s endorsement of Paul, and Dinosaurs of the Air is the sacred text.

In order to divorce maniraptorans from other coelurosaurs and theropods, you must explain away the existence of maniraptoran-like non-maniraptorans. Feduccia attempts this by claiming that all non-maniraptoran theropods are an utterly different class of animal life from maniraptorans seeing as they have “short, stubby hands” (p. 132, p. 163); they had, he opines, so reduced their forelimbs that evolving long, maniraptoran-like ones would be in contradiction of Dollo’s Law. He makes this argument with a straight face, devoting an entire chapter (Chapter 10: ‘You Can’t Go Home Again; Dollo’s Law’, pp. 129-135) to this claim.

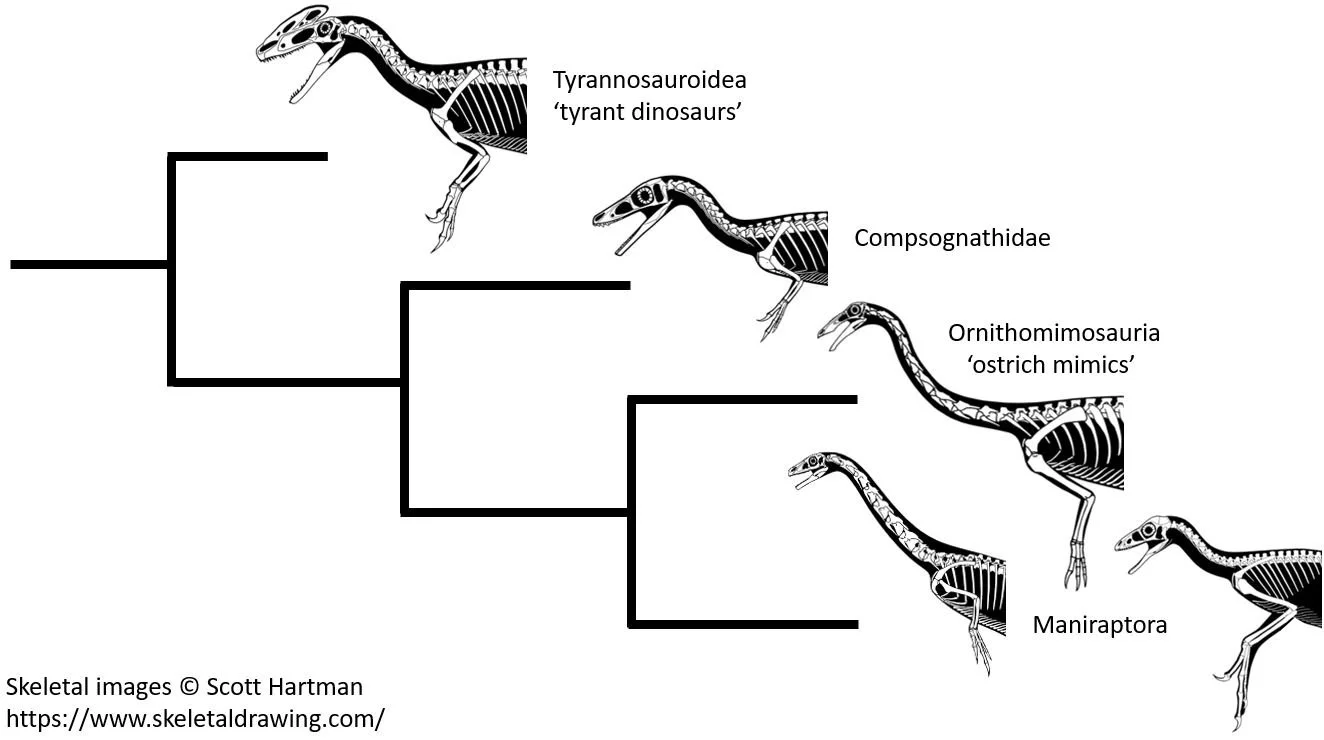

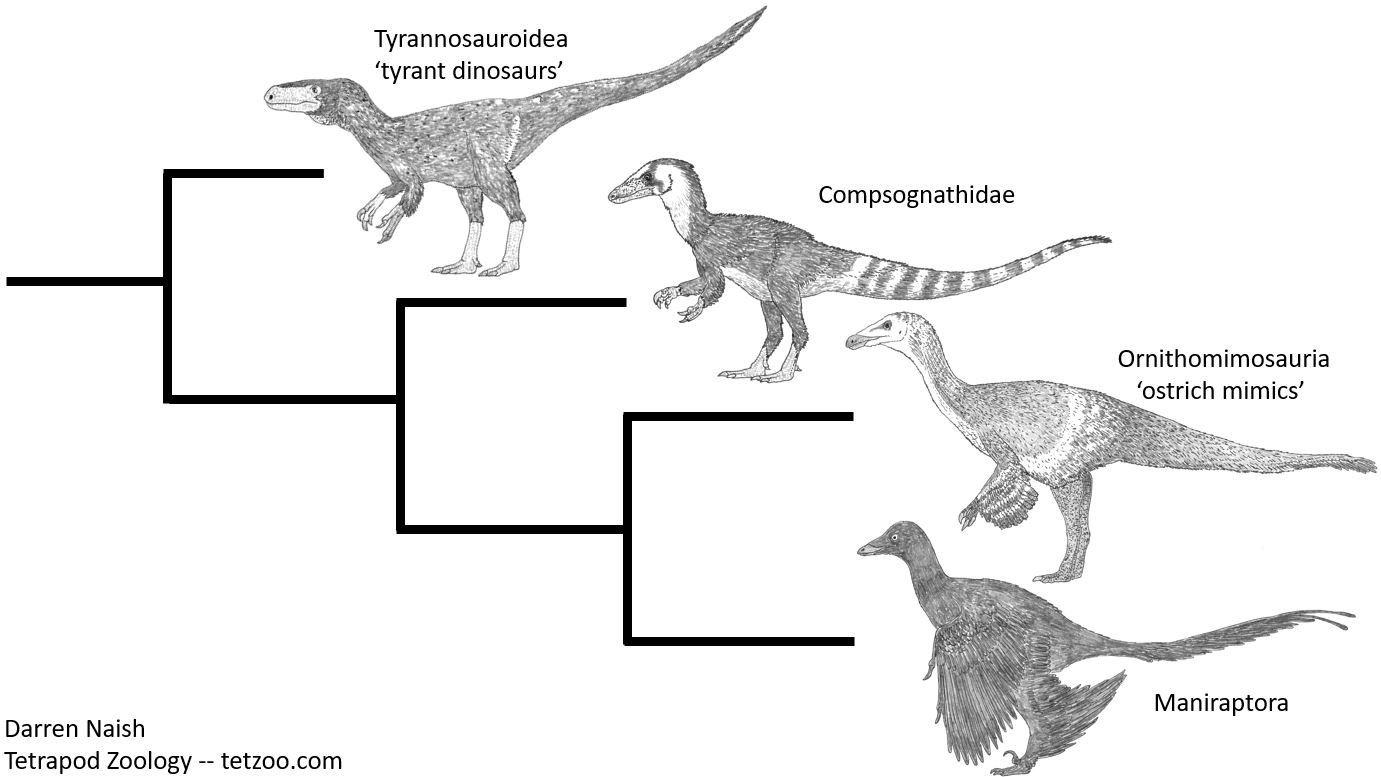

In reality, those coelurosaurs that are not maniraptorans – they include tyrannosauroids, compsognathids and ornithomimosaurs – have elongate, slender hands and limb proportions indicative of a trend in forelimb elongation within the group. They appear, if you’re prepared to admit it, very much like the animals you’d expect to be ancestral to maniraptorans. We know that Feduccia is aware of these animals since he has reason to mention them here and there in his writings (including in RTBAD), so the argumentation here can’t represent naivety; it can only be intellectual dishonesty.

Caption: contra Feduccia, it simply isn’t true that there’s a trend of forelimb reduction across those theropods surrounding maniraptorans in the family tree. As implied by the simplified phylogenetic hypothesis shown here, tyrannosauroids and ornithomimosaurs are both long-armed, like maniraptorans, and indeed are proportionally long-armed relative to theropods less close to birds. I’ve included two icons for Maniraptora because archaic maniraptorans (like therizinosaurs) are proportionally shorter-armed than the more bird-like ones. Images: (c) Scott Hartman, used with permission.

Among the newest of Mesozoic maniraptoran groups to be recognised are the unusual scansoriopterygids, and Feduccia devotes some attention to this group, often (but not always) wrongly referring to them as ‘scansoriopterids’ [sic].

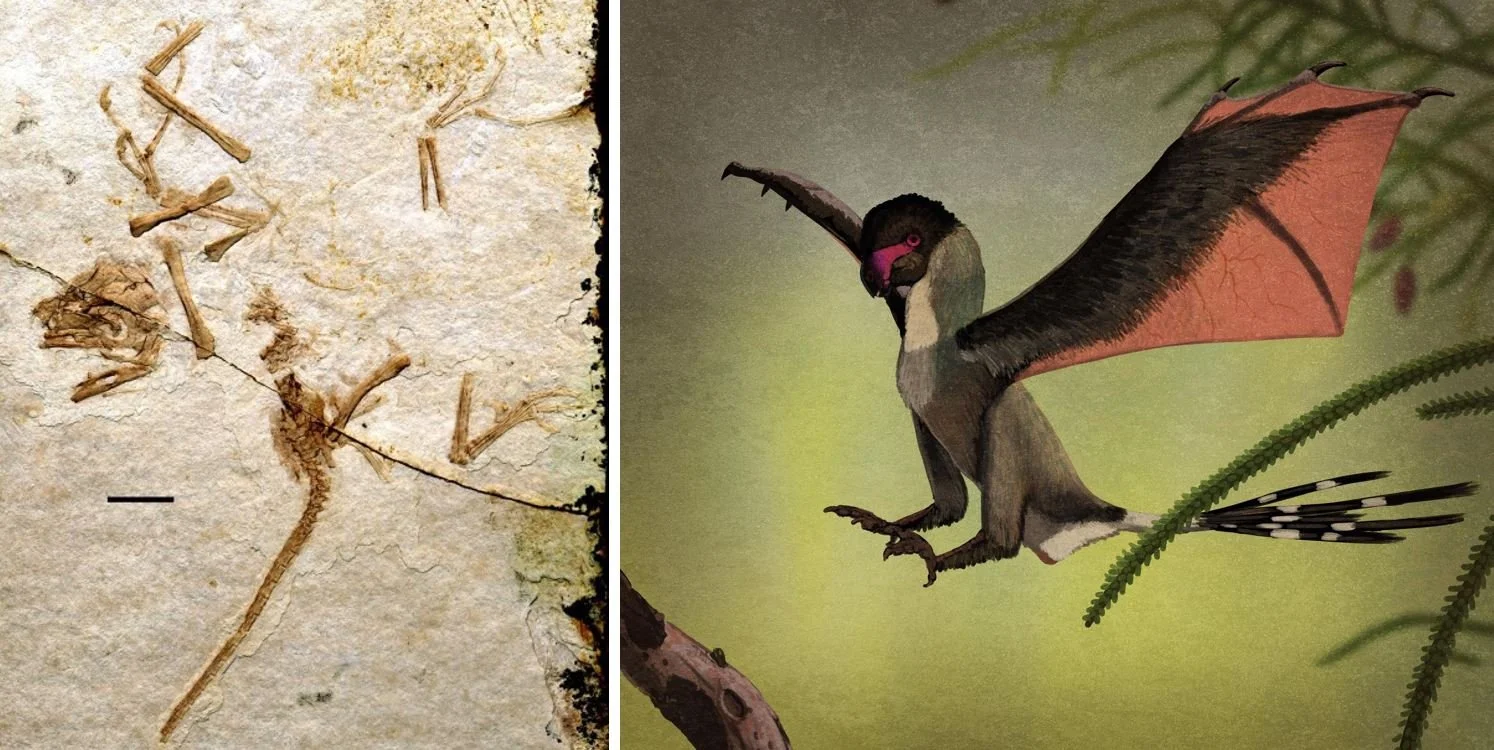

Scansoriopterygids are fascinating animals, combining small size with a short-snouted skull, probable climbing adaptations in the hindlimb and long-fingered forelimbs equipped (in some taxa, not all) with flight membranes. They look like bird ancestors of a sort if you want (note those words) birds to have evolved from small tree-climbers, and it’s not surprising that they’re of interest to Feduccia. The problem for Feduccia is that scansoriopterygids are – like other maniraptorans – part of Theropoda, allied either to oviraptorosaurs or located within the dromaeosaurid-bird clade. Feduccia’s schtick – it’s not novel to RTBAD but was published previously by Stephen Czerkas and Chongxi Yuan, and by Czerkas and Feduccia – is that scansoriopterygids “lack salient dinosaurian features” (p. 243) and “lack definite theropod characters” (p. 247).

Caption: scansoriopterygids are really fascinating animals. All are small, ranging from sparrow-sized to pigeon-sized. At left, we see the Scansoriopteryx holotype as figured by Stephen Czerkas and Feduccia. The scale bar is 10 mm! At right, a life reconstruction of Yi qi, a member of the group with membranous wings supported by a long, spur-like additional forelimb element. Images: Czerkas & Feduccia; John Conway (original here).

The hypothesis here, clearly, is that scansoriopterygids are relevant to bird ancestry but are not theropods or dinosaurs. Again, we’re seeing what Feduccia would like us to think is supported, rather than what is supported. The claim that scansoriopterygids are so different from theropods (and other dinosaurs) that they might not belong to this group is false, since theropod features are present throughout their skeletons. Furthermore, the scansoriopterygid features that Feduccia regards as making them ‘different’ from other theropods (like an especially long third finger, a propubic pelvis, partially closed acetabulum and lack of a supra-acetabular crest on the ilium) are not a problem for their theropod identity: it’s just that scansoriopterygids are weird, and most of these features evolved elsewhere within theropods anyway.

Consilience, not consensus. RTBAD’s final chapter claims to represent ‘A search for consilience, not consensus’. Feduccia uses it as a reminder of the fixed nature of his position, all while admonishing those who support a dinosaurian ancestry for birds as making extraordinary claims – predictably, he cites Sagan; p. 313 – that haven’t been subjected to appropriate scepticism. Waitaminute. The feathered maniraptorans are clearly close kin of compsognathids, tyrannosauroids and so on, which are themselves clearly close kin of allosauroids and so on. To argue at this point that maniraptorans descend from quadrupedal, arboreal non-dinosaurian reptiles is an extraordinary claim that should be subjected to appropriate scepticism. It has, and has been found not just wanting, but inconsistent with all the data we have.

Caption: maniraptorans (the theropod dinosaur group that includes birds) do not exist within a phylogenetic vacuum. That is, they are not somehow unlike all other theropods, and share numerous anatomical features with ornithomimosaurs, compsognathids and tyrannosauroids: so many, that any phylogenetic position favoured for maniraptorans has to ‘pull’ those other groups along too. This image shows a highly simplified phylogenetic hypothesis for these groups. Image: Darren Naish.

Further irony is evident from Feduccia’s reiteration of his mantra that “if it has feathers and avian flight wings, it’s a bird” (p. 312). Given the fact of evolution, what about an animal with ‘prototype’ or incipient versions of avian flight wings, and what about animals with integumentary structures that look like incipient feathers? Such animals are predicted to exist – even better, we’ve found them in the form of non-maniraptoran coelurosaurian dinosaurs – but Feduccia is here reminding us that they cannot exist within the paradigm he wants us to accept. That’s not just unscientific, it’s anti-scientific. You’re supposed to favour hypotheses and theories that are built on data, not the opposite!

All of which leads me to my final point. As might be obvious, I did not enjoy this book. I was perpetually frustrated by the author’s cherry-picking of data points and citations, his dismissal and attempting rubbishing of contemporary views of the Mesozoic world, and his persistent promotion of the idea that scientists working on dinosaurs are desperate self-popularists and megalomaniacs operating within a cult. As discussed above, his use of whataboutism, strawmanning, naïve falsification, repetition and more are obvious throughout and make RTBAD frustrating, biased and intellectually problematic.

Caption: for decades, Alan Feduccia has promoted the view that he and his colleagues “know birds”, and that those who promote the ‘birds are dinosaurs’ hypothesis do not. This has never been true, and it’s becoming increasingly less true over time. Whatever, we can turn it around and say that Feduccia certainly doesn’t “know” non-bird dinosaurs. Images: Darren Naish.

But for all this, I say from the point of view of someone fascinated by contrarian and unorthodox views in science that I cannot help but be glad that this book exists. Yes, it is a great irony that I enjoy the fact that this book has been published, and that Alan Feduccia continues to pen his contrarian, intellectually problematic, scientifically dishonest and technically misleading, wayward thoughts on the evolution and biology of dinosaurs and their kin. Do we benefit from the existence of Feduccia’s efforts to invalidate and rebuff scientific consensus, as some argue? I think the opposite is true, but I admit a guilty pleasure in enjoying the weird.

Alan Feduccia, 2020. Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs: Forays in Postmodern Paleontology. BrownWalker Press, Irvine, Boca Raton. ISBN 978-1-59942-606-8. Softback.

Acknowledgements

This review happened thanks to the generosity of Martin Neukamm of AG EvoBio. Martin has recently written a long article on Feduccia and the use of his writings by creationists: How do we know that birds are living dinosaurs? A critical analysis of creationist argumentation. I also thank colleagues who provided commentary and checked sections of the text, namely Albert Chen, John Harshman, Gerald Mayr, Mike P. Taylor and Mathew Wedel.

For previous Tetrapod Zoology article relevant to the topics covered here, see…

A quick history of tree-climbing dinosaurs, July 2008

The skin of ichthyosaurs, September 2008

Epidexipteryx: bizarre little strap-feathered maniraptoran, October 2008

Yi qi Is Neat But Might Not Have Been the Black Screaming Dino-Dragon of Death, May 2015

The Climbing, Flying Babies of Deinonychus, June 2015

The Romanian Dinosaur Balaur Seems to Be a Flightless Bird, June 2015

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 1, May 2016

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 2: Meet the Maniraptorans, May 2016

The Integrated Maniraptoran, Part 3: Feathers Did Not Evolve in an Aerodynamic Context, May 2016

The “Birds Are Not Dinosaurs” Movement, November 2017

Controversies in Ratite and Tinamou Evolution (Part I), July 2023

Refs - -

de Bakker, M. A. G., van der Vos, W., de Jager, K., Chung, W. Y., Fowler, D. A., Dondorp, E., Spiekman, S. N. F., Chew, K. Y., Xie, B., Jiménez, R., Bickelmann, C., Kuratani, S., Blazek, R., Kondrashov, P., Renfree, M. B., Richardson, M. K. 2021. Selection on phalanx development in the evolution of the bird wing. Molecular Biology and Evolution 38, 4222-4237.

Čapek, D., Metscher, B. D. & Müller, G. B. 2013. Thumbs down: a molecular‐morphogenetic approach to avian digit homology. Journal of Experimental Zoology (Molecular and Developmental Evolution) 9999B, 1-12.

Christian, A. & Dzemski, G. 2011. Neck posture in sauropods. In Klein, N., Remes, K., Gee, C. T. & Sander. P. M. (eds) Biology of the Sauropod Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis, pp. 251-260.

Currie, P. J. & Chen, P.-j. 2001. Anatomy of Sinosauropteryx prima from Liaoning, northeastern China. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 38, 1705-1727.

Feduccia, A. 1977a. The whalebill is a stork. Nature 266, 719-720.

Feduccia, A. 1977b. Hypothetical stages in the evolution of modern ducks and flamingos. Journal of Theoretical Biology 67, 715-721.

Feduccia, A. 1978. Presbyornis and the evolution of ducks and flamingos. American Scientist 66, 298-304.

Feduccia, A. 1996. The Origin and Evolution of Birds. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

Feduccia, A. 2002. Birds are dinosaurs: simple answer to a complex problem. The Auk 119, 1187-1201.

Feduccia, A. 2012. Riddle of the Feathered Dragons: Hidden Birds of China. Yale University Press, New Haven & London.

Feduccia, F. 2020. Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs: Forays in Postmodern Paleontology. BrownWalker Press, Irvine, Boca Raton.

Field, D. J., Benito, J., Chen, A., Jagt, J. W. M. & Ksepka, D. T. 2020. Late Cretaceous neornithine from Europe illuminates the origins of crown birds. Nature 579, 397–401.

Godefroit, P., Sinitsa, S. M., Cincotta, A., McNamara, M. E., Reshetova, S. A. & Dhouailly, D. 2020. Integumentary structures in Kulindadromeus zabaikalicus, a basal neornithischian dinosaur from the Jurassic of Siberia. In Foth, C. & Rauhut, O. W. M. (eds) The Evolution of Feathers. Springer Nature, Berlin, pp. 48-65.

Godefroit, P., Sinitsa, S. M., Dhouailly, D., Bolotsjy, Y. L., Sizov, A. V., McNamara, M. E., Benton, M. J. & Spagna, P. 2014. Response to Comment on ‘A Jurassic ornithischian dinosaur from Siberia with both feathers and scales’. Science 346, 434.

Larsson, H. C. E., Dececchi, T. A. & Habib, M. B. 2020. Navigating functional landscapes: a bird’s eye view of the evolution of avialan flight. In Pittman, M. & Xu, X. (eds) Pennaraptoran Theropod Dinosaurs: Past Progress and New Frontiers. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 440, American Museum of Natural History, New York, pp. 321-332.

Lingham-Soliar, T. 2001. The ichthyosaur integument: skin fibers, a means for a strong, flexible and smooth skin. Lethaia 34, 287-302.

Lingham-Soliar, T. & Wesley-Smith, J. 2008. First investigation of the collagen D-band ultrastructure in fossilized vertebrate integument. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275, 2207-2212,

Mayr, G. 2010. Response to Lingham-Soliar: dinosaur protofeathers: pushing back the origin of feathers into the Middle Triassic? Journal of Ornithology 151, 523-524.

Mayr, G., Pittman, M., Saitta, E. T., Kaye, T. G. & Vinther, J. 2016. Structure and homology of Psittacosaurus tail bristles. Palaeontology 59, 793-802.

Morell, V. 1997. The origin of birds: the dinosaur debate. Audubon 99 (2), 36-45.

Naish, D. & Barrett, P. M. 2018. Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved. The Natural History Museum, London.

Olson, S. L. & Feduccia, A. 1980a. Relationships and evolution of flamingos (Aves: Phoenicopteridae). Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 316, 1-73.

Olson, S. L. & Feduccia, A. 1980b. Presbyornis and the origin of the Anseriformes (Aves: Charadriomorphae). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 323, 1-24.

Rowe, T., Ketcham, R. A., Denison, C., Colbert, M., Xu, X. & Currie, P. J. 2001. Forensic palaeontology: the Archaeoraptor forgery. Nature 410, 539-540.

Vargas, A. O. & Fallon, J. F. 2005. The digits of the wing of birds are 1, 2 and 3. A review. Journal of Experimental Zoology (Molecular and Developmental Evolution) 304B, 206-219.

Zhang, F., Kearns, S. L., Orr, P. J., Benton M. J., Zhou, Z., Johnson, D., Xu, X. & Wang, X. 2010. Fossilized melanosomes and the colour of Cretaceous dinosaurs and birds. Nature 463, 1075-1078.