This article is too late to be at all useful when it comes to Christmas gift recommendations…

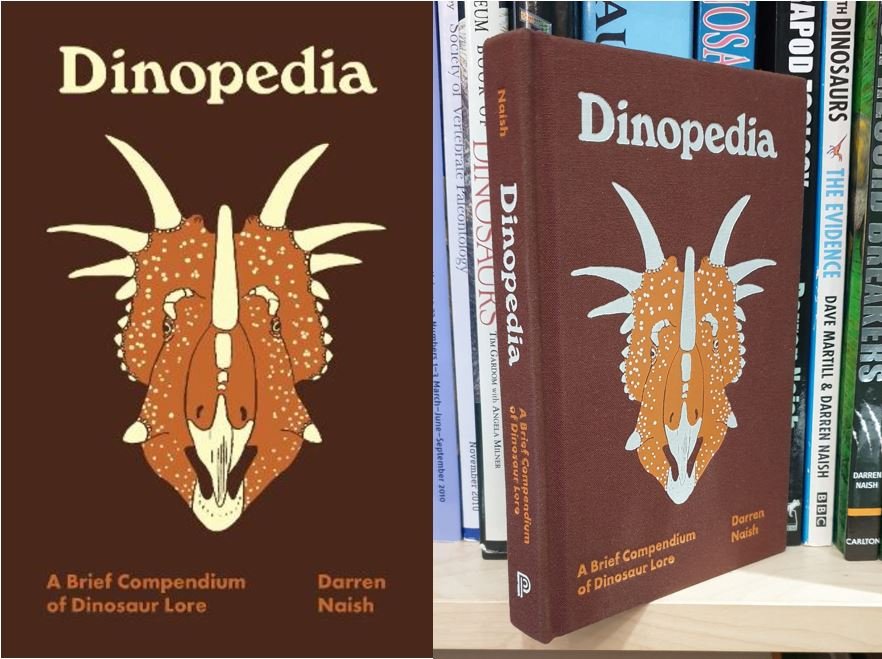

…. but I haven’t been able to act any sooner. So, yes, Dinopedia (Naish 2021) is now out and in the shops. It’s small, compact, attractive and highly affordable, and if you enjoy reading the sort of material I share here at Tetrapod Zoology you should totally get it. Here’s a brief summary of the book’s contents and the angle it takes. My primary aim in writing Dinopedia wasn’t necessarily to produce a dinosaur encyclopedia (I knew I wouldn’t be able to fit in everything I would want to cover) but, instead, to provide a personal view on ‘how we got to where we are now’.

The Renaissance, the Enlightenment, and Jurassic Park. One of my contentions is that the view of dinosaurs we have today was mostly compiled during the 1970s, 80s and 90s, partly during the so-called Dinosaur Renaissance. The dinosaurian origin of birds was confirmed during the Renaissance, the idea that non-bird dinosaurs were feathered became mainstream, the Alvarez Hypothesis on dinosaur extinction was proposed and bolstered by new data, rigorous phylogenetics was applied to hypotheses of dinosaur evolution, and the view that dinosaurs were anatomically sophisticated and behaviourally complex became mainstream too.

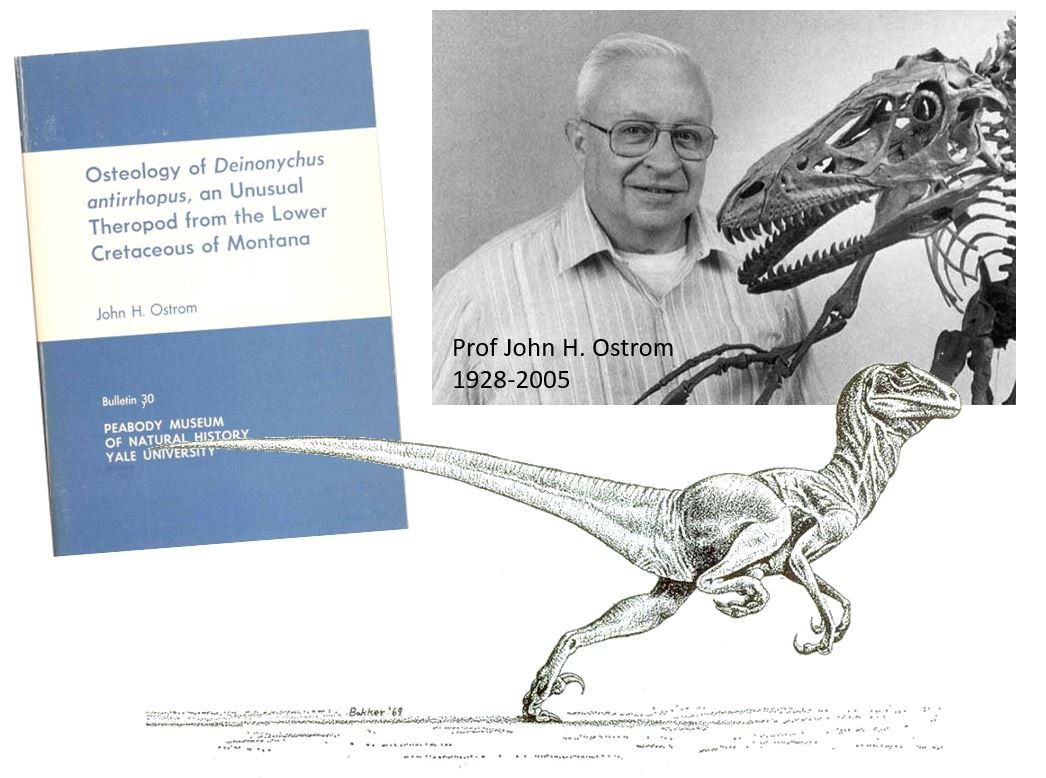

Caption: John Ostrom’s studies on Archaeopteryx, Deinonychus, hadrosaur biology and much else were mostly published between the early 1960s and late 90s. The iconic Deinonychus reconstruction is (c) Robert Bakker.

A huge number of new species and an enormous amount of hypothesis testing and detailed technical work has of course been published since those days of the 70s, 80s and 90s, but it’s that ‘late 20th century work’ that formed the intellectual bedrock of our modern view. With this in mind, the publications of such workers as Jack Horner, Halszka Osmólska, John Ostrom, Paul Sereno and others were crucial (I would have written about many other scientists if space allowed) and these people get covered in Dinopedia, as do the more ‘public-facing’ contributions of Robert Bakker and Greg Paul, both of whom are linked to what Michael Crichton wrote about in the book Jurassic Park, and to what ultimately appeared in the film.

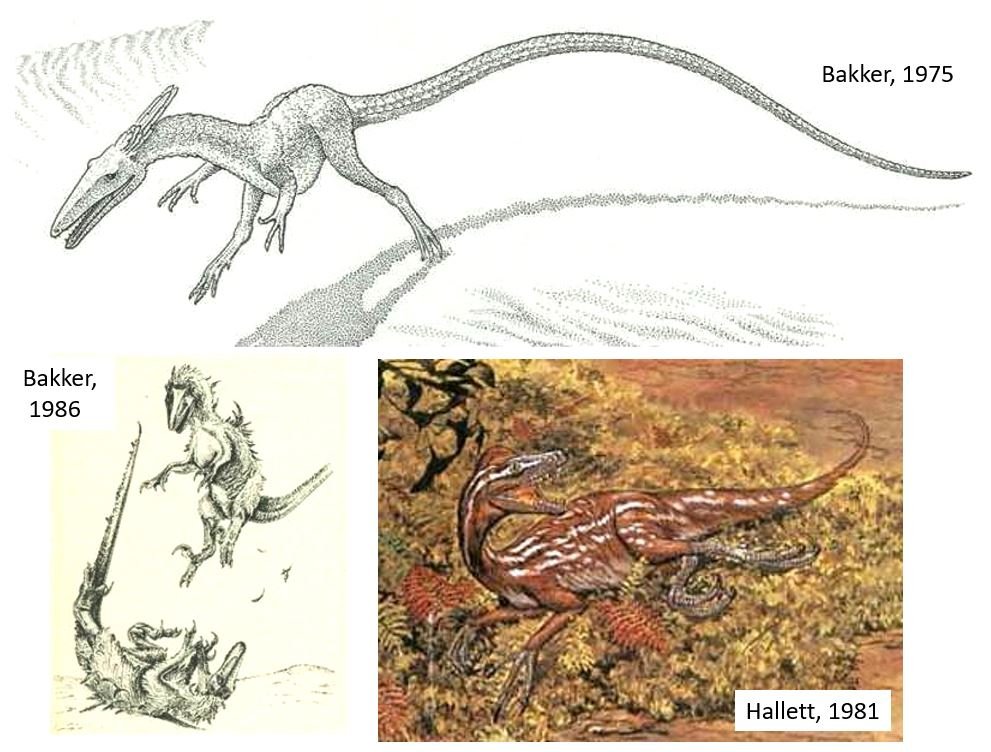

Caption: Greg Paul’s detailed anatomical studies of dinosaurs have been integral to our view of Mesozoic dinosaurs. Robert Bakker’s writings and other published works were crucial in bringing new arguments about dinosaur biology to broader attention.

Yes, the 1993 film Jurassic Park is covered at length as it’s a significant cultural milestone: the Dinosaur Renaissance was brought to the public at large, this being so important that we can speak of being in a ‘Dinosaur Enlightenment’ in the years after 1993. I do touch on Jurassic World but in less sympathetic terms, since it opted to stick with a conservative 1993 vision of dinosaurs rather than provide anything new.

People and places. The fossils integral to the Dinosaur Renaissance of course come from specific localities and geological units, including the Morrison Formation in the USA, Tendaguru in Tanzania, and the Wealden in the UK. The foundational 19th century writings and ideas of scientists like Edward Cope, Gideon Mantell, Othniel Marsh, Henry Osborn and Richard Owen were unavoidably emphasised in the Renaissance and are perpetually discussed even today.

Caption: Gideon Mantell is rightfully credited for the hard work he did on palaeontology and geology, and is forever associated with the discovery of Iguanodon (… even though the animal he found is no longer actually Iguanodon, since that name is now officially fixed on I. bernissartensis from the younger sediments of Belgium). However, the conventional heroic narrative on Mantell ignores the contributions of others, which he downplayed or sought to see expunged.

I cover all of these subjects and people in Dinopedia but the time is right to see them re-framed, partly because we have new data but also because the traditional narratives are likely wrong. Gideon Mantell, for example, wasn’t a saint and eternal philanthropist as so often implied (especially by those seeking to frame Richard Owen as an enemy of righteousness) but a desperate social climber who deliberately excluded others (most especially but not only his wife) from the narrative (I did a Twitter thread on this; it’s here). Edward Cope was an unashamed racist and sexist and not afraid to state these views in print. And the conventional story about the discovery of dinosaurs at Tendaguru is a colonial European one that deliberately excludes Tanzanian people.

Dinosaur diversity and phylogeny. Many sections of Dinopedia are devoted to the dinosaur groups themselves since a key area of interest to me is dinosaur diversity and how we’ve pieced together – or, tried to piece together! – the dinosaur family tree. Hence sections on abelisaurs, allosauroids, alvarezsaurs, megaraptorans, spinosaurids, titanosaurs, turiasaurs, tyrannosauroids and many others.

Caption: a resting Spinosaurus and the skull of the tyranosauroid Guanlong. Images: Darren Naish.

The idea that dinosaurs are a clade (a group where all species share a single ancestor) became well supported between the 70s and 90s. Previously, the dominant view was that dinosaurs were a vague collection of big archosaurs with different ancestors, this being the ‘dinosaur polyphyly’ model that was still being promoted by workers like the UK’s Alan Charig well into Renaissance times. The idea that dinosaurs split early in their history into Ornithischia and Saurischia also became supported in increasingly rigorous phylogenetic studies (e.g., Bakker & Galton 1974, Gauthier 1986, Novas 1996).

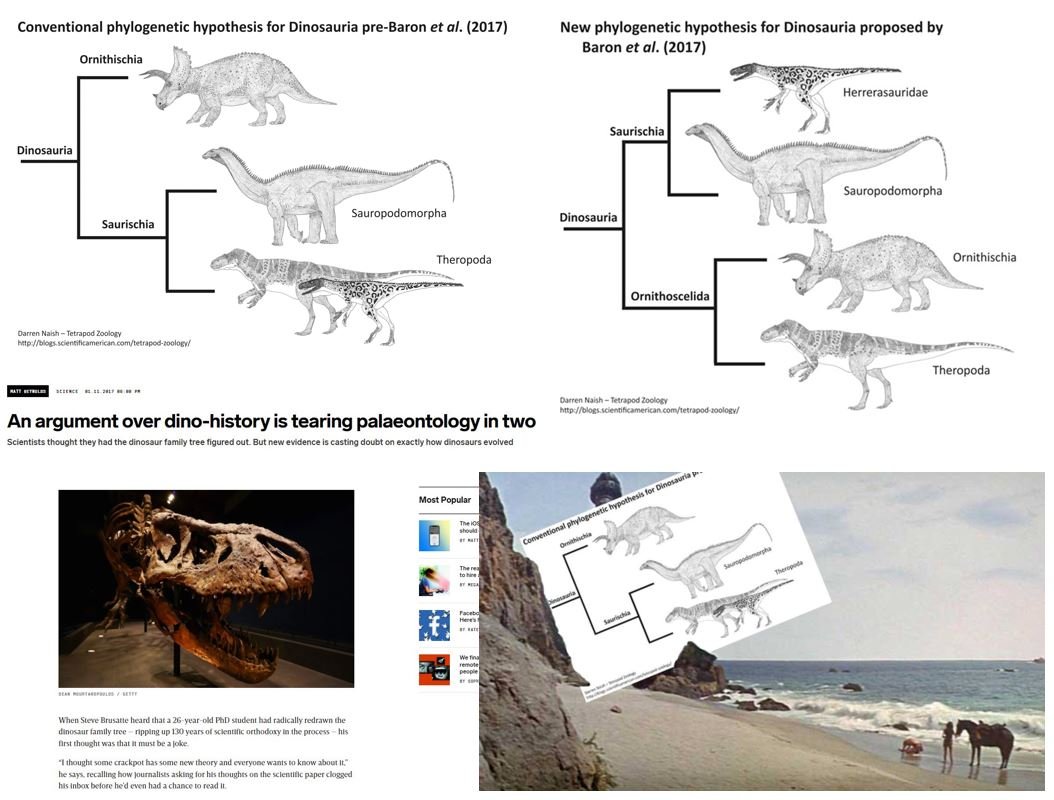

An alternative model – suggesting a sauropodomorph + ornithischian clade termed Phytodinosauria – was proposed in the 80s (Bakker 1986). Though obscure, I opted to include a discussion of it because it has recently become relevant again. The Ornithischia vs Saurischia split, you see, was challenged in 2017 when a new model for dinosaur evolution, positing the existence of the clade Ornithoscelida, was proposed (Baron et al. 2017). Numerous papers since published on the validity (or otherwise) of Ornithoscelida have resulted in an airing of several models for dinosaur relatedness. It’s among THE most-discussed issues in early 21st century dinosaur science, and it thus seemed right to cover this discussion at reasonable length.

Caption: an Ornithoscelida montage, featuring cladograms from my 2017 article on the initial Baron et al. (2017) paper.

Extinction, extrapolation, and birds. Part of our interest in dinosaurs comes from their famous extinction 66 million years ago, a topic made especially exciting by the suggestion that it had an extraterrestrial cause. I cover the KPg (Cretaceous/Paleogene) Extinction Event, one of my points being that we might have downplayed how horrible it really was (HT to those palaeoartists going out of their way today to reconstruct the relevant horrific scenes that must have occurred).

Combine an ‘extraterrestrial link’ with ever-present speculation on the idea that things might have been very different had the event not occurred, and you can’t ignore the dinosauroid (Russell & Séguin 1982, Naish & Tattersdill 2021), an imaginary humanoid dinosaur that has also been a mainstay in popular dinosaur texts since the 80s.

Caption: your regular reminder that the idea of feathers on non-bird dinosaurs was around for some time prior to the discoveries of the 1990s. It always was a good idea.

The fact that some dinosaur groups did survive the extinction – we call them birds – is an important part of the dinosaur story. Bakker and Paul (and others) were putting feathers on Velociraptor-type dinosaurs during the 80s but it was Chinese finds from the 1990s that made ‘feathered dinosaurs’ an unarguable part of the canon. They made Liaoning Province in China world-famous for its dinosaur fossils.

The evidence that birds are theropod dinosaurs is about as good as it possibly could be, but massively well-represented in popular media from the 70s to today is the contrary view – mostly promoted by Alan Feduccia – that birds simply can’t be dinosaurs and must come from elsewhere. My view as a writer interested in the history of science is that we cannot and should not ‘pretend away’ bad or wrong ideas as if they didn’t exist.

Caption: Alan Feduccia has made a career from proclaiming that ‘birds are NOT dinosaurs’ and is still at it, as demonstrated by the 2020 publication of the hilariously titled Romancing the Birds and Dinosaurs (kinky!). We shouldn’t ignore this view as anti-scientific rhetoric (even if it is): this stuff has been faithfully reported in the popular press and has had a major influence on public and scientific thought.

Birds themselves, incidentally, are given reasonable coverage in Dinopedia. Scientists who specialise on Mesozoic dinosaurs have usually not been that interested in summarising our knowledge of bird evolution and diversity after the Mesozoic (after all, we can’t all be experts on everything), meaning that the people who’ve covered Cenozoic bird history the most are the same ones who promote the ‘birds are not dinosaurs’ stuff, Feduccia in particular. That’s not good: it’s been under-appreciated how misleading Feduccia’s writings on birds are. A growing number of scientists have expertise in both Mesozoic and Cenozoic dinosaurs, and things are set to improve.

Finally, studies on functional morphology, taphonomy, ecology, histology and much else have substantially improved our understanding of dinosaur behaviour and biology in recent decades. All of this stuff goes hand-in-hand with what I’ve described above. The problem is that these ideas are hard to summarise for a book of this format. I mostly worked them into the entries on the individual dinosaur groups. However, Dinopedia entries on hadrosaur nesting colonies, on ‘Nanotyrannus’ (and its implications for dinosaur growth strategies) and pneumaticity are relevant to biology and behaviour.

And that about sums things up. As should be clear, it’s inevitable that my main emphasis in the book is on dinosaur diversity and how the groups are related (so, expect lots of clade names – sorry, they are impossible to avoid). The book should, however, otherwise serve as an introduction to the dinosaur world as it stands in 2021.

Caption: in case it isn’t obvious yet, I did all the illustrations in Dinopedia myself, including the cover art. Here’s a montage of most of the images put together. Image: Darren Naish.

Thanks to those who’ve bought copies and shared their thoughts, or shared images of their own copies. You can buy Dinopedia yourself here. It’s cheap and compact.

And that’s that. This will almost certainly be the last article here before the start of 2022, so have a great Christmas and New Year!

For articles on various of the topics mentioned here, see…

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014

Ornithoscelida Rises: A New Family Tree for Dinosaurs, March 2017

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 1, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 2, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 3, June 2018

Announcing Dinopedia, Out September 2021, March 2021

Humanoid Dinosaurs Revisited Again: Russell and Séguin’s Dinosauroid at (Nearly) 40 Years Old, August 2021

Please consider supporting this blog - and the other stuff I do - at patreon! Thank you :)

Refs - -

Bakker, R. T. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. Penguin Books, London.

Bakker, R. T. & Galton, P. M. 1974. Dinosaur monophyly and a new class of vertebrates. Nature 248, 168-172.

Baron, M. G., Norman, D. B. & Barrett, P. M. 2017. A new hypothesis of dinosaur relationships and early dinosaur evolution. Nature doi:10.1038/nature21700

Gauthier, J. 1986. Saurischian monophyly and the origin of birds. Memoirs of the California Academy of Science 8, 1-55.

Naish, D. & Tattersdill, W. 2021. Art, anatomy and the stars: Russell and Séguin’s dinosauroid. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences https://doi.org/10.1139/cjes-2020-0172

Novas, F. E. 1996. Dinosaur monophyly. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16, 723-741.

Russell, D. A. & Séguin, R. 1982. Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid. Syllogeus 37, 1-43.