Today brings the sad news that British palaeontologist Dr Angela Milner has died following a short illness. I’ve heard this news from several friends and colleagues, in particular from the Natural History Museum’s Dr Paul Barrett….

Caption: Dr Angela Milner with various of the fossils she worked on; these images come from this article; it includes some interesting recollections from Dr Milner herself.

Dr Milner, formerly Head of the Fossil Vertebrates Division in the Department of Palaeontology at London’s Natural History Museum, was predominantly an expert on Paleozoic amphibians. However, her research interests and experience were broad and she also published on lizards, plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, Archaeopteryx, ornithischian and theropod dinosaurs, and more. She is perhaps most prominently remembered for co-describing the remarkable Early Cretaceous theropod Baryonyx walkeri with Alan Charig (Charig & Milner 1986, 1990, 1997), a seminal event in late 20th century dinosaur history. She coauthored the Natural History Museum’s official book on dinosaurs: the very successful The Natural History Museum Book of Dinosaurs (Gardom & Milner 1993), itself the direct ancestor of Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved (Naish & Barrett 2018), the NHM’s main current dinosaur-themed work.

Like many people involved in British vertebrate palaeontology, I knew Angela and was assisted by her on numerous occasions over the years, and I’m saddened to hear of her passing. My condolences to her husband Andrew (also a palaeontologist), and to her friends, colleagues and the others who knew her.

There’s little doubt that some extensive and lengthy reviews of Dr Milner’s life and work will appear in time. I’m not in a position today to produce anything like a biographical article on Dr Milner’s work, but in the event of this sad news it feels appropriate to share the following text on the discovery of Baryonyx walkeri: this was originally published in my 2008 book The Great Dinosaur Discoveries (Naish 2008)…

“Heavy Claw” and the spinosaurs. England is the scientific ‘home’ of the dinosaurs, and continues to yield new dinosaur species. One of the most surprising is a new large theropod discovered in Lower Cretaceous Wealden sediments at Ockley, Surrey, in 1983, by amateur collector William Walker. He discovered parts of a giant claw, a small claw bone, and a tail bone.

Caption: a now very familiar image of William Walker, holding the original Baryonyx claw while visiting the NHM in London. I like that - entirely coincidentally - Peter Snowball’s artistic depiction of a Wealden scene is behind him, and I believe that that’s Alan Charig in the background. I’m pleased that I was able to get this image used in Naish (2008).

After repairing the broken tip of the large claw, Walker realized that these fossils belonged to something quite unusual. He took them to the British Museum (Natural History) in London, which today is called the Natural History Museum. Here they were examined by fossil reptile experts Alan Charig and Angela Milner. This was clearly an important discovery, and a visit to the clay pit revealed other bones that seemed to belong to the same animal.

A full excavation. The resulting excavation and preparation revealed much of the skull and a partial skeleton belonging to an animal perhaps 9 m (30 ft) long. The huge claw, which measures over 30 cm (12 in) along its curve, belonged to the hand, and the skull is narrow and crocodile-like, with an expanded snout tip. The animal appeared to be a highly unusual theropod. However, some palaeontologists suggested that it might be a crocodilian or even a late-surviving rauisuchian (a group of crurotarsan archosaurs otherwise restricted to the Triassic).

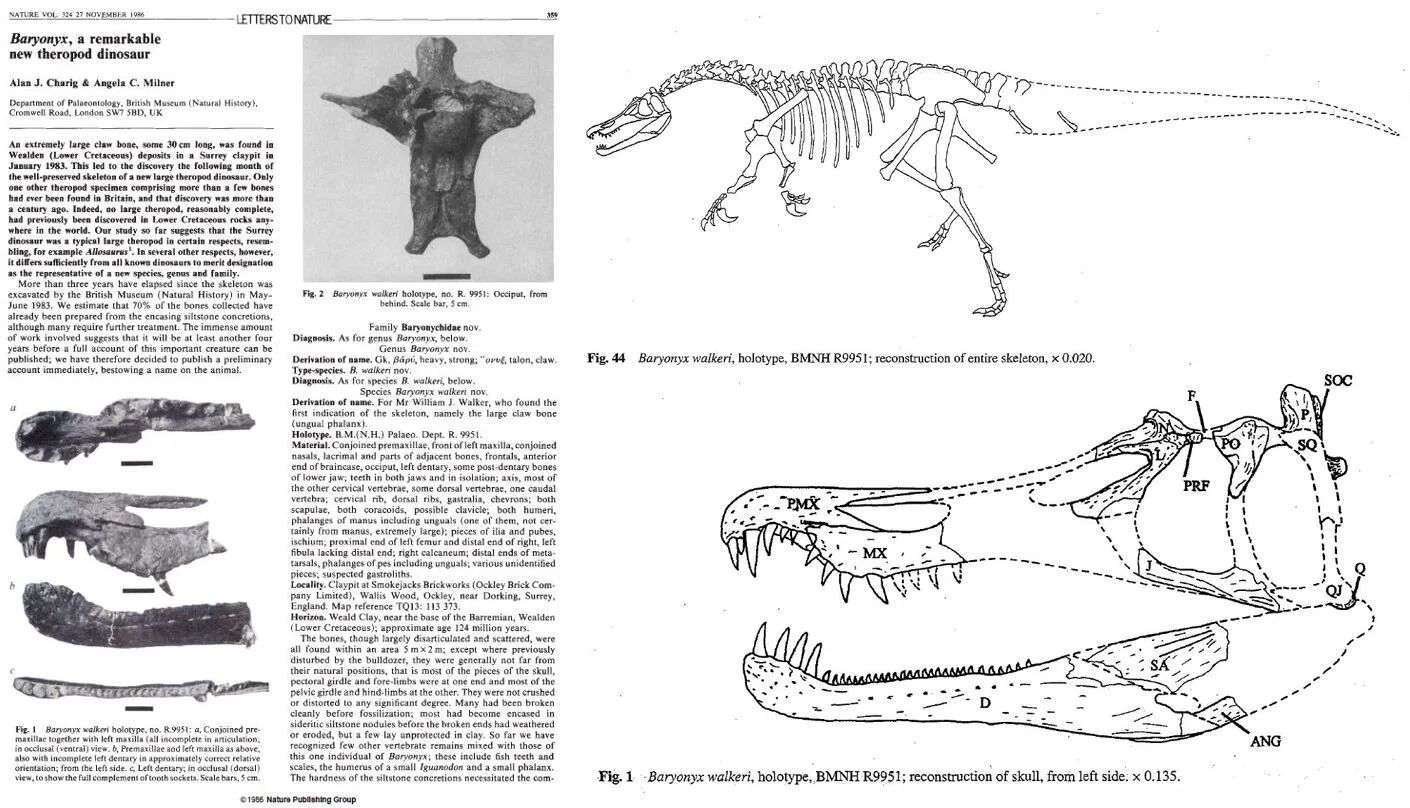

Caption: at left, the front page of Charig & Milner’s (1986) initial descriptive paper on Baryonyx. At right, the skeletal reconstruction and skull reconstruction provided in the 1997 monograph (Charig & Milner 1997).

In 1986, Charig and Milner published a preliminary description. The new dinosaur was definitely a theropod after all, and they named it Baryonyx walkeri, meaning ‘Walker’s heavy claw’. It was regarded as so unique that it was worthy of its own family, which they named Baryonychidae. The rocks of the Wealden have been studied and collected from for over 150 years, so the discovery of a completely new kind of large predatory dinosaur in the English Wealden was nothing short of amazing. The media soon nicknamed Baryonyx ‘Claws’ in a punning reference to the popular film Jaws, and the dinosaur became an international sensation.

Caption: the notion of the quadrupedal Baryonyx has mostly died out today, since we now know that the robust upper arm bones of baryonychines and other spinosaurids likely weren’t used in weight support. I don’t know what role Angela Milner had in the look of the Invicta Baryonyx figure - shown here - but its quadrupedal pose might be a holdover from the view Charig and Milner favoured during the mid-1980s. Image: Darren Naish.

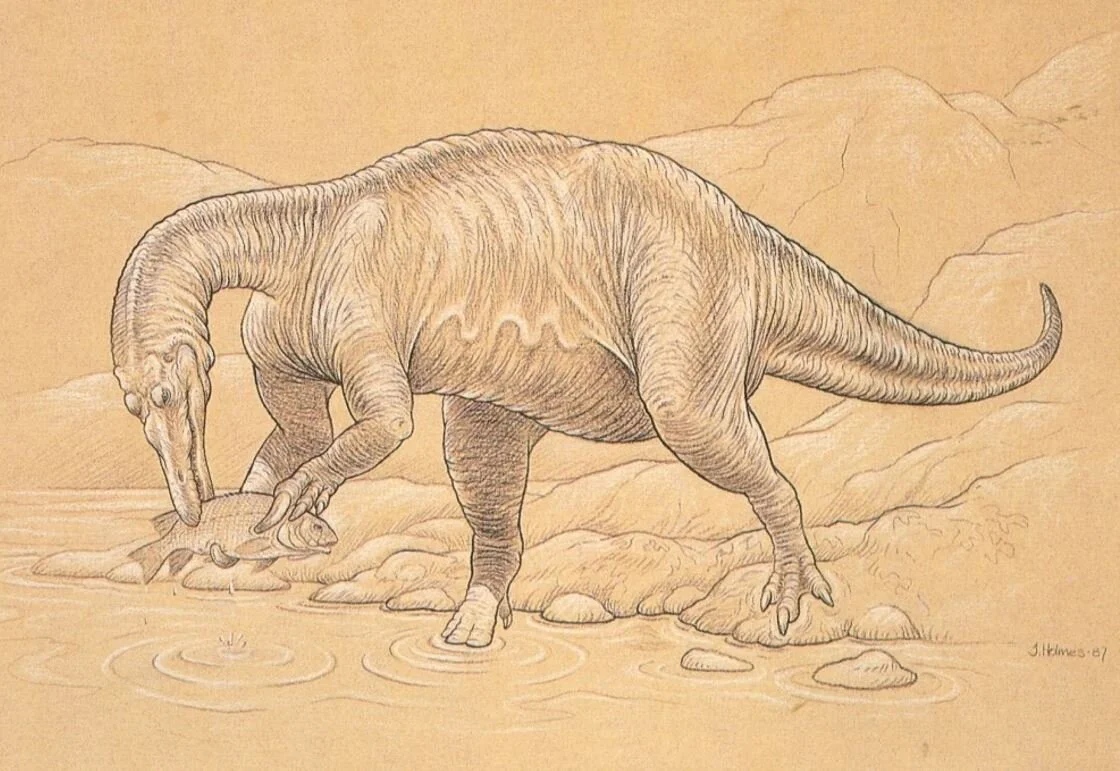

Massive arms. Baryonyx had a massively muscled upper arm bone, and this caused Charig and Milner to suggest that it crouched or walked quadrupedally, making the species unique among theropods. Its crocodile-like skull, large thumb claws, and finely serrated teeth indicate that it might have been a fish eater, and this was confirmed by the discovery of fossil fish scales preserved in its stomach region.

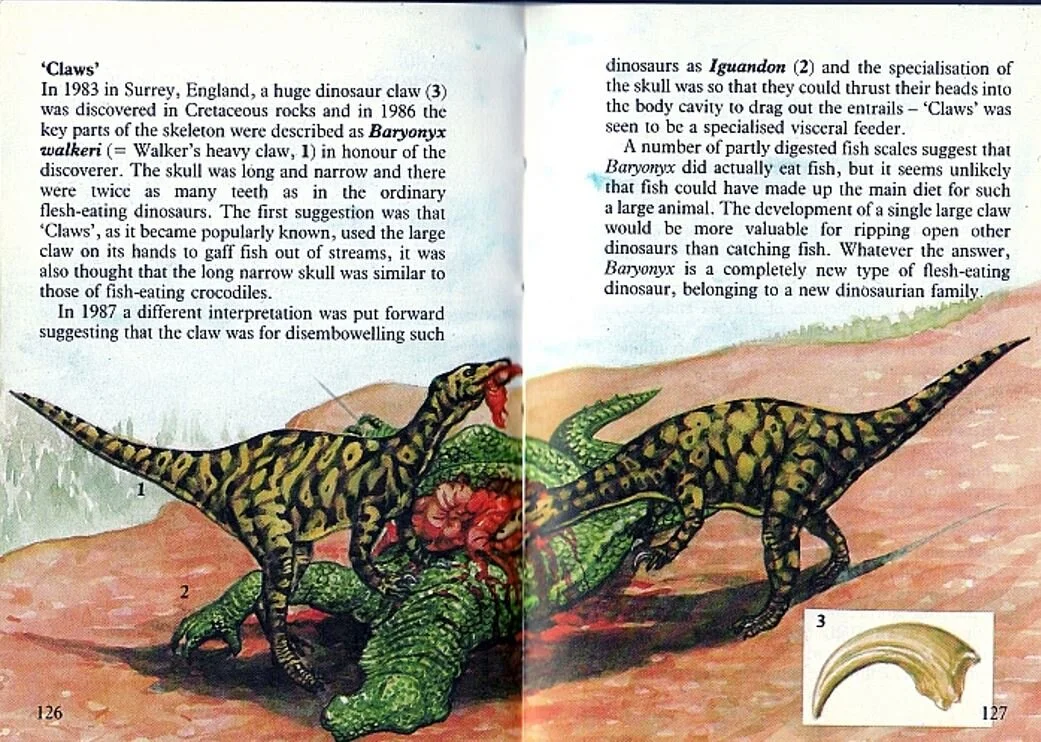

An alternative hypothesis, proposed in 1987, was that Baryonyx might be a specialized scavenger that used its huge claw to rip carcasses open and its long snout to probe into them. Although this behaviour is plausible, the idea that a giant terrestrial carnivore could find enough carcasses to survive is unlikely.

Caption: the ‘scavenging Baryonyx’ hypothesis (put forward by mammalogist Andrew Kitchener) will, for me, always be associated with this piece of art by Jenny Halstead from Beverly Halstead’s 1989 Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life. I stole this scan of the image from here at Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs.

Solving the enigma. The affinities of Baryonyx proved controversial. Charig and Milner stated that too little was known to come to any conclusions, but they did note that details of the snout bones vaguely recalled those of Dilophosaurus and similar Early Jurassic theropods. However, during the late 1980s, French palaeontologist Eric Buffetaut and American writer and illustrator Greg Paul noted that the remains of Baryonyx seemed to be quite similar to those of the enigmatic African theropod Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Both dinosaurs have an unusual upturned tip to the lower jaw, and also share features of the teeth and tooth sockets. Accordingly, Baryonyx was not such an enigma after all, but a member of Spinosauridae.

Caption: among the first artistic reconstructions depicting Baryonyx are those produced by John Holmes, who produced numerous works for the NHM over the years. This illustration is one of several produced by Holmes; it was available as a postcard from the NHM shop. I have one in my own collection.

New fossils and analysis have demonstrated that this theory is correct. A close relative of Baryonyx, Suchomimus, was named from Niger in 1998, a Brazilian spinosaurid (Irritator challengeri) was named in 1994, and numerous fragmentary fossils of Baryonyx (mostly teeth) have been reported from England, Germany, Spain and Portugal. All spinosaurids seem to have been long-jawed predators that behaved quite differently from deep-skulled theropods like megalosaurs and allosaurs. Rather than providing evidence for quadrupedality, the robust arm bones of these theropods may have helped them to tackle or pick up prey.

In memory of Dr Angela Milner.

Refs - -

Charig, A. J. & Milner, A. C. 1986. Baryonyx, a remarkable new theropod dinosaur. Nature 324, 359-361. [T7]

Charig, A. J. & Milner, A. C. 1990. The systematic position of Baryonyx walkeri in the light of Gauthier’s reclassification of the theropoda. In Carpenter, K. & Currie, P. J. (eds), Dinosaur Systematics: Approaches and Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, pp. 127-140.

Charig, A. J. & Milner, A. C. 1997. Baryonyx walkeri, a fish-eating dinosaur from the Wealden of Surrey. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum 53, 11-70.

Naish, D. 2008. The Great Dinosaur Discoveries. A & C Black, London.