Well, here we are the final part in this long-running series. Thanks for sticking with it, and thanks for all the brilliant insight and annotation so many of you have provided in the comments. The series has been a real winner in terms of attracting visitors, and commenters especially.

If you’re new here, you need to see the first part in the series to know what the deal is: who pitched the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) contention, and why? Links to the other parts in the series – which variously cover Cenozoic mammal taxonomy and its relevance to the TMDD contention, Morrison Formation stratigraphy and extent, sauropod taxonomy and species boundaries, sauropod population density and possible endemism, and Jurassic plants and their nutritional value – are included at the bottom of this article as well as in the sidebar. The previous three articles looked at several assumptions specific to the TMDD contention. Here, we look at the fourth and final of those assumptions. And we then wrap things up! Hey, it’s been fun.

Caption: a montage of things relevant to previous parts of this series. Upper left: Cenozoic megamammals relevant to the TMDD contention. Upper right: a Bakker (1993) depiction of Morrison stratigraphy and dinosaurs. Bottom: Maraapunisaurus, as reconstructed by Slate Weasel. Images: Darren Naish, Bakker (1993), Slate Weasel, CC0 (original here).

Assumption 4: most – if not all – specialists on the relevant dinosaur groups are wrong, and not really expert at all. Inherent to the TMDD contention is the idea, or at least the strong inference, that specialists on the animals concerned have screwed up, and have failed to get a good handle on species-, genus- and family-level variation in Morrison Formation sauropods. These experts, so the story goes, have mistaken juveniles, subadults, adults, old adults and perhaps even the sexes of the same species as distinct species, and even as members of wholly distinct family-level lineages! In short, the view that sauropod specialists hold, and have held, on these animals is woefully and hideously wrong. This goes for the Grand Old Men of the field (Charles Gilmore, John Hatcher, Werner Janensch, Othniel Marsh, Charles Mook, Henry F. Osborn, Elmer Riggs, Alfred Romer and so on), those who published their work throughout recent decades (Robert Bakker, David Berman, John McIntosh, Peter Dodson and so on) and the vast majority of contemporary, active specialists (Paul Barrett, Matthew Bonnan, Kenneth Carpenter, John Foster, Jerry Harris, Mike Taylor, Virginia Tidwell, Emanuel Tschopp, Paul Upchurch, Mathew Wedel, John Whitlock, Jeff Wilson and so on and on). Could the TMDD contention be right? Could all of these experienced (and mostly scientifically careful, thorough and often brilliant) workers all be dead wrong on such basic things?

Caption: Charles Whitney Gilmore (1874-1945), former curator of the Division of Vertebrate Paleontology at the United States National Museum (USNM), successful monographer of stegosaurs, ornithopods and theropods, and prolific describer of ceratopsians, crocodilians, ichthyosaurs… and sauropods. Image: public domain, original here.

Here I very much have ringing in my ears the bogus call to ‘arguments from authority’, in addition to Sagan’s mantra “there are no authorities, only experts”. Nevertheless, my strong feeling is that… no, these many people were and are not wrong, and we are not set for some grand implosion of sauropod diversity whereby, say, all 16 or so Morrison Formation diplodocids can be absorbed into a supposedly more acceptable lower number.

The relevant experts didn’t and don’t hold the views they did and do just… because. Rather, they’ve stated and demonstrated in their technical publications how actual evidence supports the ‘many species’ model, and a great many of them have a track record of publishing good work, and of demonstrating what we might term appropriate expertise. Even better, the idea that some or many of the sauropods in question might be considered ontogenetic or sexual morphs of one another has already been thrashed out in the literature (and in blogs, in particular at SV-POW!) (Taylor et al. 2011, Wedel & Taylor 2013, Hedrick et al. 2014). The conclusions overwhelmingly support the many species model.

Caption: a (now somewhat dated) montage by Scott Hartman, showing three diplodocines compared. AMNH 223 (the one in the middle) is labelled here as Diplodocus longus, whereas recent study (Tschopp et al. 2015) indicates that it’s likely the same species as the animal previously called Seismosaurus hallorum, but now included in Diplodocus. Here’s your evidence right there that experts have already vetted and tested the possibility of synonymising these animals. Image: (c) Scott Hartman.

Conclusion: no, Barosaurus, Diplodocus and other diplodocine diplodocids cannot be lumped together into one or two species; there are several apatosaurine species which can’t be lumped together either; rebbachisaurids and dicraeosaurids are separate groups from diplodocids; Suuwassea is not the juvenile of some previously named diplodocoid; the haplocanthosaurs are something else again, as of course are the various camarasaurs and brachiosaurs and so on. In other words, both species- and genus-level diversity was high in the sauropod assemblages concerned, and the multi-species model is valid. Your personal incredulity, which I think is misplaced anyway, is not sufficient to demolish it.

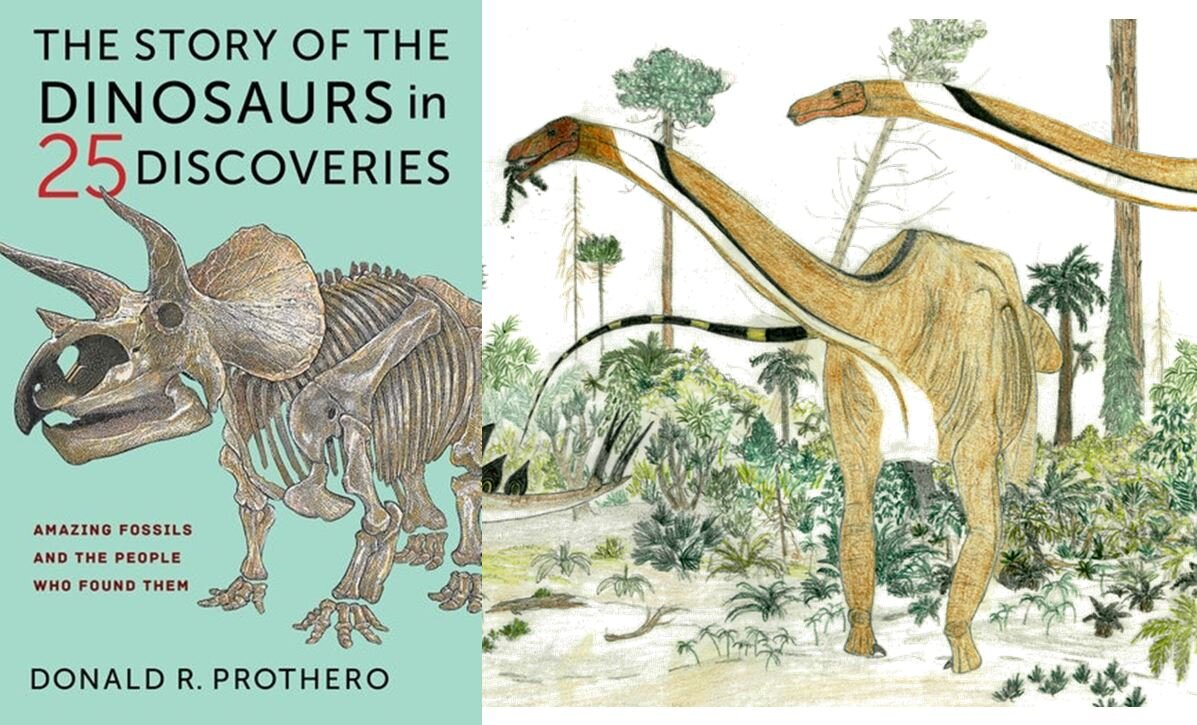

Caption: in case you didn’t know, this series of articles was mostly written in response to contentions made in Don Prothero’s 2019 book The Story of the Dinosaurs in 25 Discoveries (Prothero 2019). Images: Darren Naish.

No, there are not too many damn dinosaurs. To wrap-up, the idea that there are too many damn dinosaurs – and Late Jurassic sauropods in particular – is misplaced, and based on a naïve understanding of the science that’s been done on these animals and their ecosystems. It’s also based on arm-waving and intuition more than anything else. To repeat the various points (made across this series) in summarised form…

Several fossil megamammal groups have proved oversplit: brontotheres, North American rhinos and indricotheres among them. This was widely recognised by specialists and (relatively) easily resolved once it was tested. This situation is not at all similar to the fact that there are multiple species of Morrison Formation sauropod. See Part 2 for more on this issue.

The idea that we can reduce the number of relevant species by synonymising them is countered by work which has already discussed and evaluated these sorts of proposals and found them wanting. See Part 3 for more on this issue.

The view that Morrison environments were packed with sauropods, and that five, six, seven or more species were living in the same place, at the same time, is not accurate. The species concerned lived across a vast area, across a timespan of at least 7 million years, and most specific areas were – at any one time – inhabited by just two or three species. See Part 4 for more on this issue.

Giant adult sauropods quite probably did not occur at high populations, meaning that their impact on ecosystems and potential for co-occurrence was different from expectations. Abundant babies and juveniles may have formed the bulk of the population. The total adult sauropod population of the Morrison Formation – of all species combined – was likely much lower than we would predict based on community structure in mammals. See Part 5 for more on this issue.

The mammal faunas that people sometimes point to when saying TMDD! are not appropriate as analogues, because they’re Holocene and hence depauperate. Pre-Holocene megamammals existed at diversities more comparable to those of sauropods. But sauropods aren’t mammals anyway, on which read on. See Part 6 for more on this issue.

The assumption that sauropods (and other big dinosaurs) were mammal-like in having continent-wide ranges might be wrong. For reasons that are still not well understood, the relevant dinosaur species and genera may have been endemic to smaller areas than those expected on the basis of megamammal distribution. It was a different world, with a different community structure. There really were places where several species and genera inhabited the same area. See Part 6 for more on this issue.

The idea that sauropod-dominated ecosystems were energy-poor and unable to support populations of large animals is wrong. See Part 7 for more on this issue.

The people who have supported the multi-species model are a noble bunch who’ve done a lot of sterling, high-quality work. Sure, they’re only human and have no doubt got things wrong, but it’s a big ask to imply that all of these people are wrong about the taxonomic and phylogenetic models they’ve supported and still do support.

And that about sums things up. There are not too many damn dinosaurs.

For the previous article in this series, see…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 1, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 2, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 3, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 4, April 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 5, May 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 6, May 2020

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 7, May 2020

For previous TetZoo articles on sauropods, brontotheres, giraffes and related issues (linking where possible to wayback machine versions), see…

Giraffes: set for change, January 2006

Biggest…. sauropod…. ever (part…. I), January 2007

Biggest sauropod ever (part…. II), January 2007

The hands of sauropods: horseshoes, spiky columns, stumps and banana shapes, October 2008

Thunder beasts in pictures, March 2009

Thunder beasts of New York, March 2009

Sauropod dinosaurs held their necks in high, raised postures, May 2009

Inside Nature’s Giants part IV: the incredible anatomy of the giraffe, July 2009

Testing the flotation dynamics and swimming abilities of giraffes by way of computational analysis, June 2010

Paul Brinkman’s The Second Jurassic Dinosaur Rush, March 2011

The sauropod viviparity meme, May 2011

Necks for sex? No thank you, we’re sauropod dinosaurs, May 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part I), December 2011

The Second International Workshop on the Biology of Sauropod Dinosaurs (part II), January 2012

Greg Paul’s Dinosaurs: A Field Guide, February 2012

Junk in the trunk: why sauropod dinosaurs did not possess trunks (redux, 2012), November 2012

That Brontosaurus Thing, April 2015

Unusual Giraffe Deaths, November 2015

Burning Question for World Giraffe Day: Can They Swim?, June 2016

10 Long, Happy Years of Xenoposeidon, November 2017

The Life Appearance of Sauropod Dinosaurs, January 2019

Refs - -

Bakker, R. T. 1993. The dinosaur renaissance. In Calhoun, D. (ed) 1993 Yearbook of Science and the Future. Encyclopaedia Brittanica (University of Chicago), pp. 28-40.

Wedel, M. J., & Taylor, M. P. 2013. Neural spine bifurcation in sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation: ontogenetic and phylogenetic implications. Palarch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 10 (1): 1-34.