Many of us interested in the more arcane side of natural history will be aware of that body of literature that seeks to explain the biology, behaviour and history of living things within the words of a complex, multi-authored work known as The Bible. I refer of course to the creationist literature; to that number of books and articles whose authors contend that animals known from fossils simply must accord with the stories and descriptions of the Bible, and whose authors furthermore contend that the Earth and its inhabitants must have come into being within the last few thousand years.

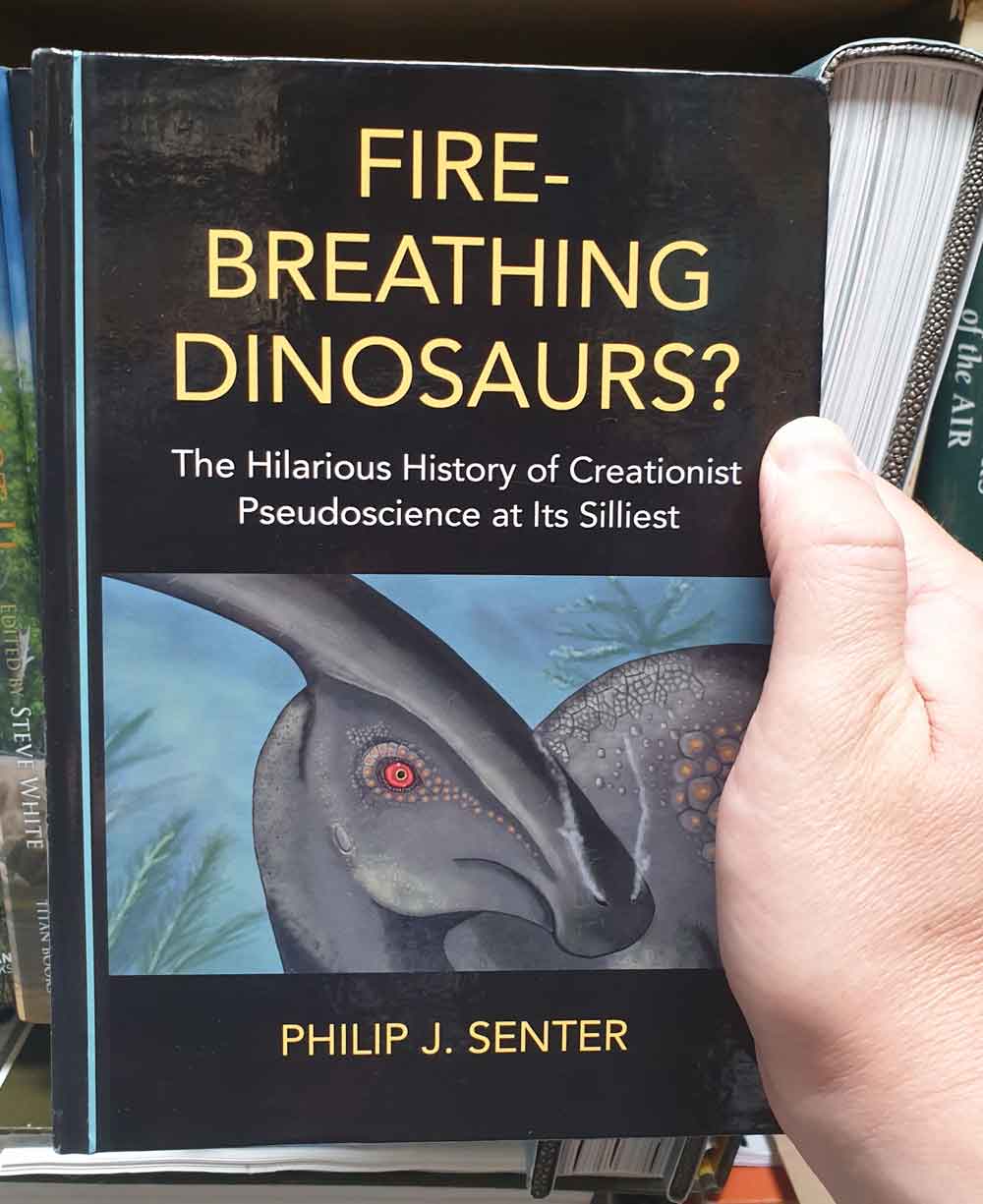

Caption: a smouldering Parasaurolophus: the cover art for the book, by Leandra Walters. Image: (c) Leandra Walters/Senter (2019).

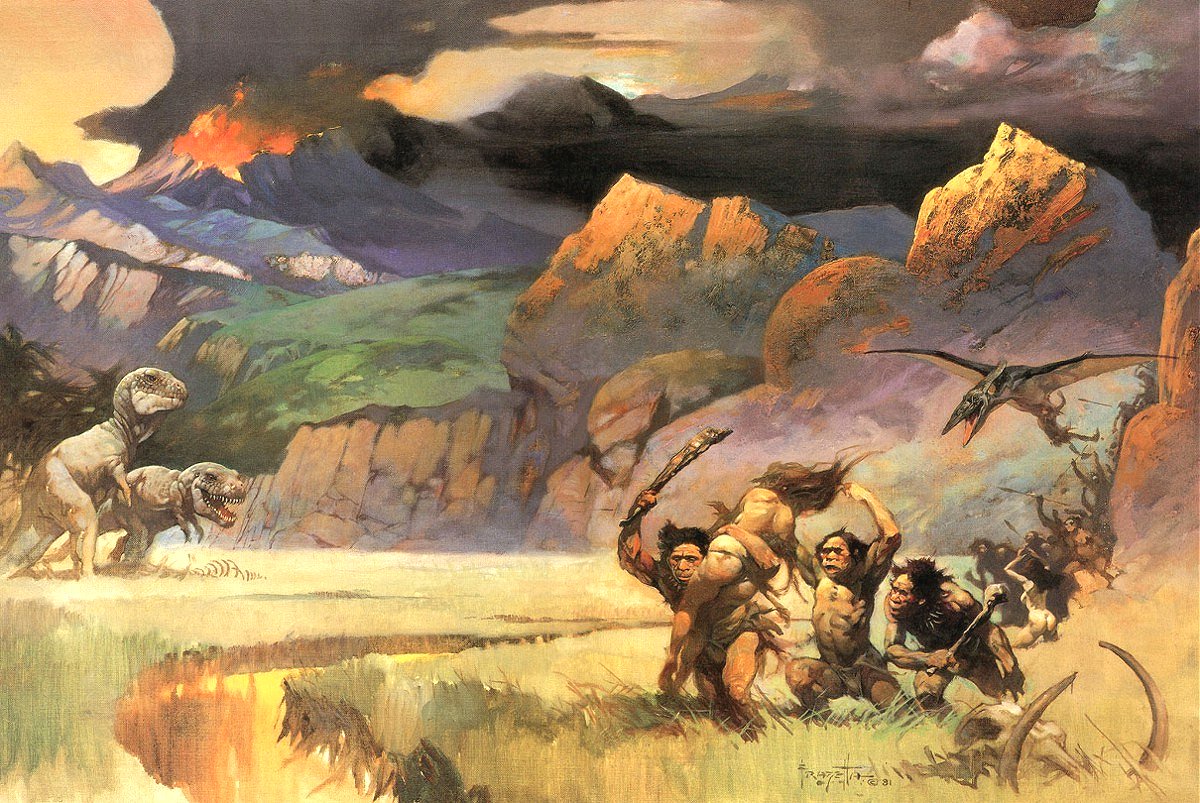

Creationist authors – the most familiar include Ken Ham, Kent Hovind and Duane Gish – have argued that non-bird dinosaurs and other fossil animals were inhabitants of the Garden of Eden, that predatory species like Tyrannosaurus rex ate water melons and sugarcane before The Fall, that humans and animals like Tyrannosaurus lived alongside one another during the early days of the Earth’s creation, that evolution cannot have happened, except when it did as species emerged from their different ancestral kind (or baramins), and that animals like Tanystropheus, tyrannosaurs and pterosaurs were seen and written about by people, and are responsible for the mythological creatures mentioned or described in the Bible and other ancient texts. Leviathan and Behemoth of The Bible, Grendel of the medieval epic Beowolf, the fire-breathing dragons of the Middle Ages and so on must – creationist authors contend – be descriptions of human encounters with giant reptiles otherwise known as fossils. And, yes: you read that right… creationist authors have argued, apparently seriously, that fire-breathing dragons must be descriptions of encounters with animals like dinosaurs and pterosaurs. So… they… breathed fire, then.

Caption: the Bible specifically states that the first few books of the Old Testament are not meant to be taken literally. Despite this, a number of Young Earth creationists promote a view of the ancient world where people lived alongside allosaurs and pterosaurs and so on. If you’ve seen a version of this page mentioning lemonade and homosexuality, it’s a spoof (the original text does not include that section of text). Image: (c) Ken Ham, Dinosaurs of Eden.

Over the past several years, Fayetteville State University biologist and palaeontologist Philip J. Senter has published a great many technical scientific articles evaluating the various claims and models of creationist authors; some of his articles are short-form versions of the text included in this new book (cf Senter 2017). His approach is to accept their proposals as valid scientific hypotheses, and not to knock, mock or discount them out of hand from the start. Remember that point; we’ll be coming back to it. This approach means that creationist claims can be considered tested in the empirical sense. It should also be noted that Senter is an Orthodox Christian with qualifications in theology, so his sympathetic and scientifically ‘honest’ approach to creationist claims should not and cannot reasonably be taken as any sort of attack on the Christian faith that the relevant creationists are part of. The fact that Senter is himself religious mean that he can make the argument (should he wish to) that the bad calls and bs put out by creationists is not just ‘bad science’ but ‘bad religion’, too. I’ve heard the same argument from other scientists who maintain an active religious life.

Caption: the book reviewed here is not the first time Senter has written about the ‘fire-breathing dinosaurs’ idea. Image: (c) Skeptical Inquirer.

For completion, and for those who don’t know, I should add that Senter is also an experienced and prolific author of studies devoted to more conventional palaeontological fare: descriptions of new dinosaur species, analyses of phylogenetic patterns, interpretations of functional morphology, and so on. The technical papers of his that I’ve found most useful and interesting include Senter et al. (2004) and Senter (2007) on dinosaur phylogeny, Senter (2006, 2009) on palaeobiology, and Senter (2005), Senter & Robins (2005), Senter & Parrish (2005) and Bonnan & Senter (2007) on dinosaur functional morphology.

Caption: the handsome cover of Senter (2019).

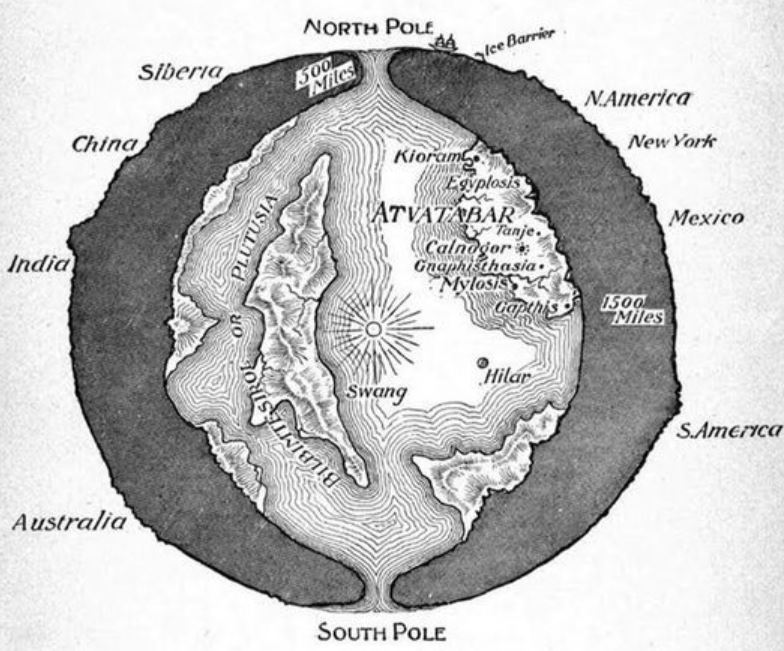

The early chapters of this book evaluate and discuss the creationist contention in general and the relatively young history of the entire movement. The impact of John Whitcomb and Henry Morris’s 1961 book The Genesis Flood is obvious, as is the fact that their arguments fail evaluation (Senter 2019). Nevertheless, their influence was such that – from the early 1970s onwards – a number of like-minded individuals were promoting Whitcomb and Morris’s vision, and were in particular arguing that ancient and medieval writings and works of art make explicit reference to dinosaurs and other long-extinct animals. Senter (2019) uses the term apnotheriopia (meaning ‘dead beast vision’) to describe the tendency of creationist author to interpret monsters in literature and art as long-extinct reptiles.

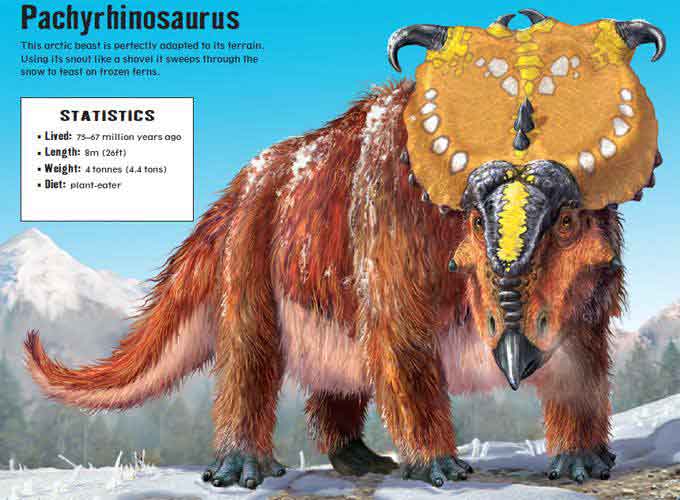

If apnotheriopia is one of your guiding principles, it ‘follows’ that the fire-breathing dragons canonical to Eurocentric, Christian mythology should be interpreted as dinosaurs or similar reptiles, and that such creatures were dragonesque fire-breathers. So integral has the whole fire-breathing thing been to these authors that they’ve proposed fire-breathing for dinosaurs of several sorts (most frequently hadrosaurs) as well as for pterosaurs and the giant Cretaceous crocodyliform Sarcosuchus (Senter 2019). You might know of one or two cases in which this idea has been mooted. Senter’s book shows that numerous authors have engaged with this vision and written about it. The sheer quantity of this literature is daunting – I was going to say ‘impressive’ but this absolutely seems like the wrong word – and Senter has clearly gone to some considerable trouble to obtain it. He must own a pretty hefty personal library of creationist volumes, and I’m reminded of a statement he makes in one of his papers, wherein he notes that collecting and reading creationist literature on dinosaurs and other extinct animals is one of his “guilty pleasures”.

Caption: some creationist authors have argued that certain dinosaurs could have functioned just like the living bombadier beetles AND SPEWED FIRE!!!!1! One minor issue: bombadier beetles don’t spew fire, they eject hot liquid. Image: Patrick Coin, CC BY-SA 2.5 (original here).

Indeed, the bulk of this book – the long section that runs from chapters 5 through 15 – is a chapter by chapter analysis of the different fire-breathing claims made by creationist authors. These people have, I’ve been surprised to learn, come up with six different mechanisms for fire production in extinct archosaurs. Senter (2019) goes through each in turn, in appropriate detail. In some cases, the proposed mechanisms are total non-starters (no, dear creationists, pterosaurs couldn’t house flammable gases inside their head crests) and can be brushed aside quite swiftly. But in other cases, Senter (2019) has to go down the rabbit-hole of gas chemistry, anatomy and biochemistry, and the history of burns and gaseous explosions in human medicine. All fascinating and well-argued stuff, and full of amazing nuggets of information.

Caption: Parasaurolophus - beloved posterchild of the fire-breathing dinosaurs movement - flames an anachronistic Ceratosaurus, a familiar image from the creationist literature. I believe that this is from one of Ken Ham’s books.

The conclusion, overwhelmingly, is that creationists have been spouting ill-informed (or uninformed) nonsense in coming up with their various fire-breathing fantasies. The proposals concerned are inconsistent with biology, chemistry and physics, and cannot have been present in animals governed by the rules that apply to the living things of planet Earth.

Caption: it’s well known that the crests of lambeosaurine hadrosaurs were hollow, and contained connected internal tubes and chambers. Were these used in the production of fire? No. Image: Sullivan & Williamson (1999).

The book’s final two chapters are connected to the fire-breathing creationist movement, but tackle rather different topics: the origin of dragons as a whole, and the true identity of the biblical Behemoth (Leviathan is covered too), often said by creationists to be a description of a sauropod or similar dinosaur. These two chapters are among the most interesting and valuable in the book.

Caption: why have creationists been so big on the ‘dragons were fire-breathing dinosaurs’ thing? I think it’s partly an effort to attract children to their cult. It isn’t coincidental that most illustrations of fire-breathing dinosaurs appear in books written for children, like this one by Duane Gish.

Even today, the notion that dragons must surely have been based on giant reptiles or reptile-like animals still unknown to science is not unpopular, and is occasionally promoted in the cryptozoological and conspiracy literature. But it’s wrong: the whole idea of dragons as we mostly imagine them (winged, fire-breathing, horned monsters, clad in armour-like scales and equipped with massive limbs and talons) is a mistake, and one that emerged, incrementally, from more mundane origins.

Senter (2019) shows, via statements made in antiquarian literature and by cross-referencing their use of terms, that the term dragon was used – unambiguously, consistently and repeatedly – for snakes, especially for large kinds like pythons. Yes, dragons were snakes. But how does this explain the limbs, wings, fire-breathing and other embellishments? These were added over time, mostly by medieval European authors who were no longer familiar with giant snakes and had heard rumours that dragons could fly (Senter puts this unfamiliarity down to the rise of Christianity and the closing of pagan temples). Feathered wings were added during the 8th century, which then became membranous wings thanks to inventive artists. By the 13th century, dragons were being depicted as quadrupeds (Senter 2019). What about the fire-breathing thing? If dragons were snakes, then some dragons were venomous, and capable of creating a burning sensation in human tissue. Embellish and augment this idea sufficiently, and the concept of fire-breathing winged mega-snakes has emerged. Chinese dragons, by the way, have an entirely independent origin and were mostly based on mammals; Senter (2019) even says that they shouldn’t be called dragons.

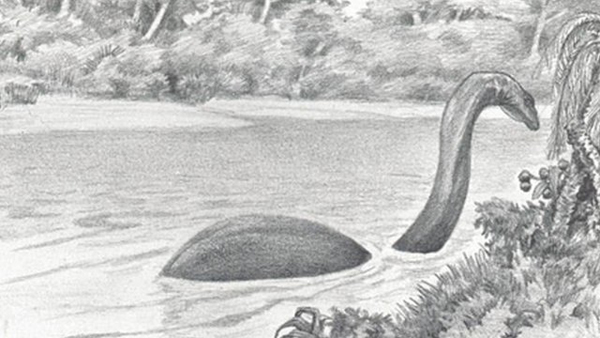

Caption: in this most famous depiction of Leviathan - that by Gustave Doré, dating to 1865 - Leviathan is depicted as a monstrous winged serpent of the seas. Image: public domain (original here).

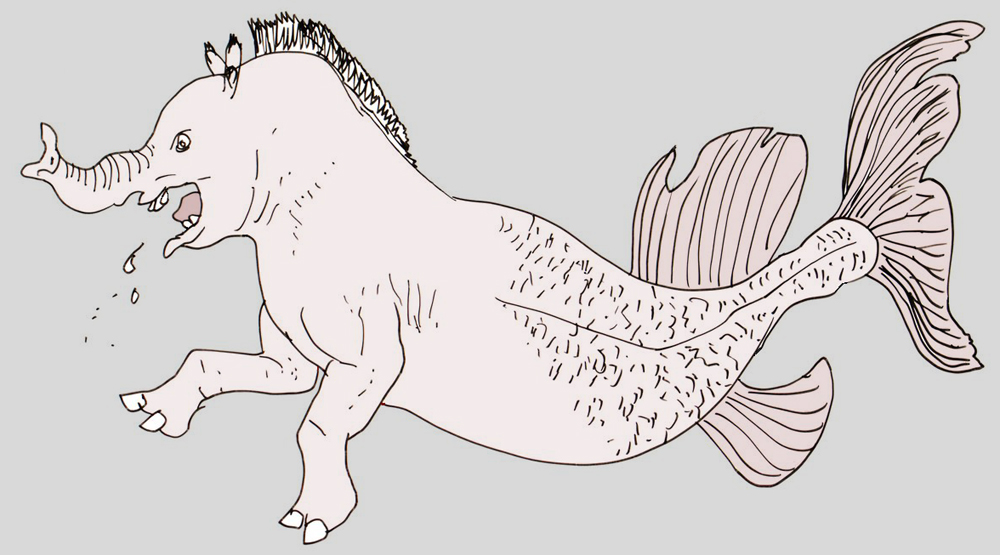

Finally, Senter (2019) also shows – I think convincingly – that the creationist interpretations of both Leviathan and Behemoth of the book of Job are entirely erroneous, but so are the interpretations favoured by the majority of sceptical and ‘mainstream’ authors. I don’t want to steal all of Senter’s thunder, but… Leviathan and Behemoth were both gargantuan mythical serpents, and those authors who have interpreted these creatures as dinosaurs, crocodiles, or big mammals have misunderstood key descriptive phrases, or have been led astray by mistranslations or misinterpretations of the original Hebrew (Senter 2019).

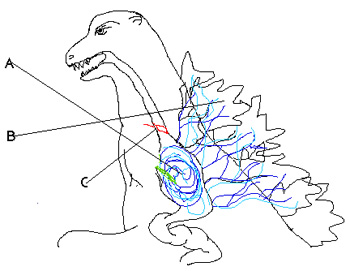

Caption: Senter (2019) uses cartoons like this one to emphasise that Behemoth never was a dinosaur, elephant or hippopotamus, but “a demonic entity that the ancient Hebrews envisioned as a serpent” (Senter 2019, p. 142). The caption to this illustration is “Will be real Behemoth please stand up?”. Image: Senter (2019).

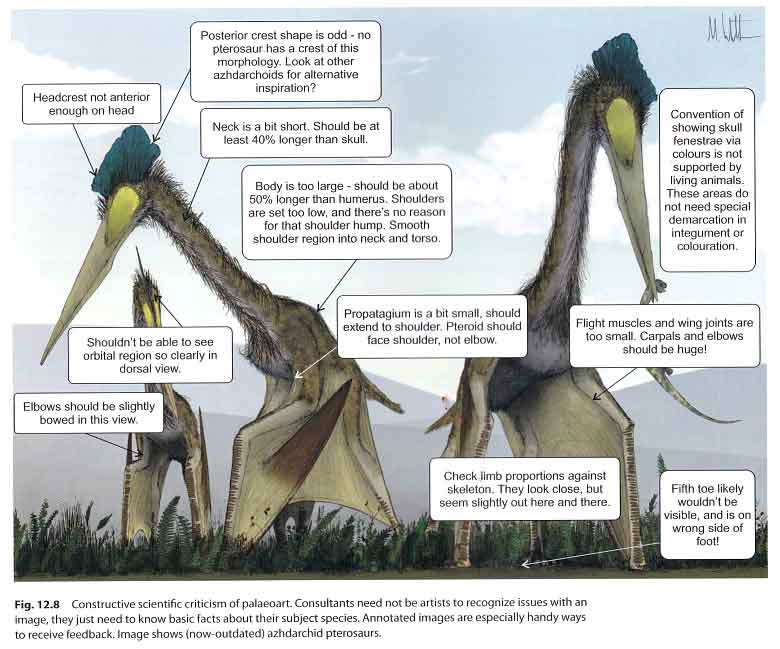

This book is not that lengthy. There are 201 pages, but 45 of them are occupied by a very voluminous bibliography. Plus the book is hardback (or, this edition is, anyway), so appears bulkier than it would do with soft covers. It’s well illustrated and includes numerous colour photos, diagrams of many sorts, and colour cartoons explaining and depicting Senter’s responses to creationist proposals and arguments. There are two things about the images that I dislike. Firstly, some of the colour photos chosen to depict given extinct taxa are quite anachronistic: things would be improved, I feel, if more contemporary reconstructions took their place. Secondly, the colouring used for many of the cartoons is less than great. I mean, the cartoons themselves – which I assume Senter penned himself (he’s a pretty good and competent artist) – are great, but it looks like they’ve been coloured-in with colouring pencils.

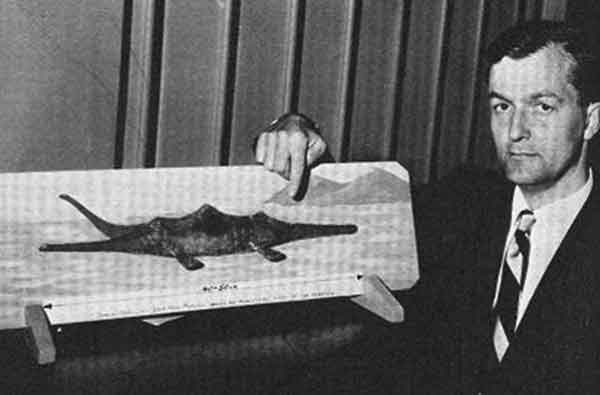

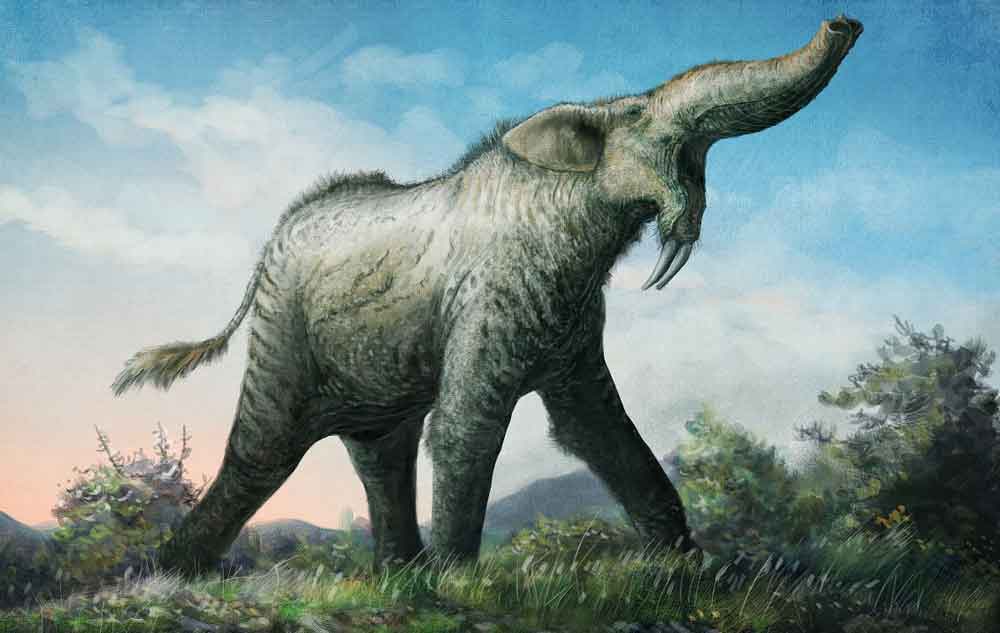

Caption: need to feature a depiction of an extinct animal? I, personally, would prefer it if a more up-to-date and aesthetically pleasing image were used in place of this one. Senter (2019) uses several images of models similar to this one when discussing extinct taxa. Image: I’ve been unable to find a source for this picture; it comes from that bottomless pit of hell called pinterest.

So far I’ve been kind to this book. I enjoyed reading it and think it’s a worthy addition to the literature. But I’m afraid that, by the time I’d finished reading it, I’d taken quite a disliking to it, for three reasons.

The first thing I dislike is the way in which creationist claims and proposals are framed. I’m not exactly a fan of creationism, creationist arguments or creationists themselves and I certainly agree with Senter (2019) that the authors who’ve pushed creationist agendas have been scientifically clueless, and/or have sought to wilfully promote anti-scientific gas-lighting. Senter (2019) even finishes the book with a prayer, praising creationist authors for their dogged promotion and energy but wishing and praying that they might make the world a better place by re-directing their energies to something good or constructive. Fair enough.

I do think, however, that Senter (2019) overdoes it in framing creationists and their ideas as ‘silly’ and ‘ridiculous’; Senter (2019) does this throughout the whole of the book such that its entire approach is “let’s all laugh at those whacky creationists” (the subtitle, I’ll remind you, is The Hilarious History of Creationist Pseudoscience at its Silliest). In my opinion (I’d be interested to know if others agree), the book would have worked better if Senter’s approach throughout was neutral and without the mocking. I’ve mocked creationists myself, for sure (Naish 2017), but I’m not about to write an academic book on the subject of their writings. Indeed, given that I’m familiar with Senter’s many papers where he tests creationist claims (all are written in scholarly fashion and use language and phrasing typical for peer-reviewed science), I was surprised to see him follow this path, and I had the impression throughout that it was done in an effort to make the text lighter, more fun, and more appealing. I understand the need for that but I’m saying that – surely – there must have been another way.

Caption: Senter (2019) compares creationist decisions to those made by a character called ‘Silly Chef’ (the muppet-like individual in the middle) who features in a series of cartoons that appear throughout the book. Image: Senter (2019).

Finally on this point, it might be doubtful that the creationists and would-be creationists who are the focus of Senter’s (2019) discussion will ever read this book (it’s abundantly clear that they don’t, or haven’t, read any of the other literature criticising or demolishing their arguments; if they have, they do a good job of making it appear that they haven’t). But by framing the entire book as a “let’s all laugh at those whacky creationists” exercise, the people who might benefit most by reading it will (I assume) be thoroughly put off. Admittedly, this is a moot point anyway in view of my third negative point, but hang on, we’ll get to that in a minute.

The second thing I dislike concerns Senter’s use of humour. This book is well written, and well edited too (I didn’t spot a single typo). But the prose is ruined by Senter’s repeated, very weird forays into simile and metaphor. They are, I’m sorry to say, not just bad, but among the worst examples of writing I can recall. Not only did I not ever find his quips funny, I mostly found them tortuous and daft and I winced every time the text introduced yet another one. I feel bad for saying this and apologise for seeming like a miserable bastard. I disliked this stuff so much that I feel the book would be much improved if all of it was stripped out. And if you’re thinking that – surely – the relevant sections of text can’t be all that bad. Well, here’s one example…

“The misunderstandings and mistranslations necessary to force such an interpretation are almost as bad as those that would be required to infer that the story of David killing Goliath is about a vampire grapefruit preparing a pleasant pile of purple petunias as a fluffy pillow for the happily napping saber-toothed tiger that it keeps as a pet and is convinced for no apparent reason that it is a gigantic German bunny with adorable tiny little ears that wiggle ever so preciously when you gently blow into them” (Senter 2019, p. 144).

There are many other examples of this sort of thing. They ruin the book.

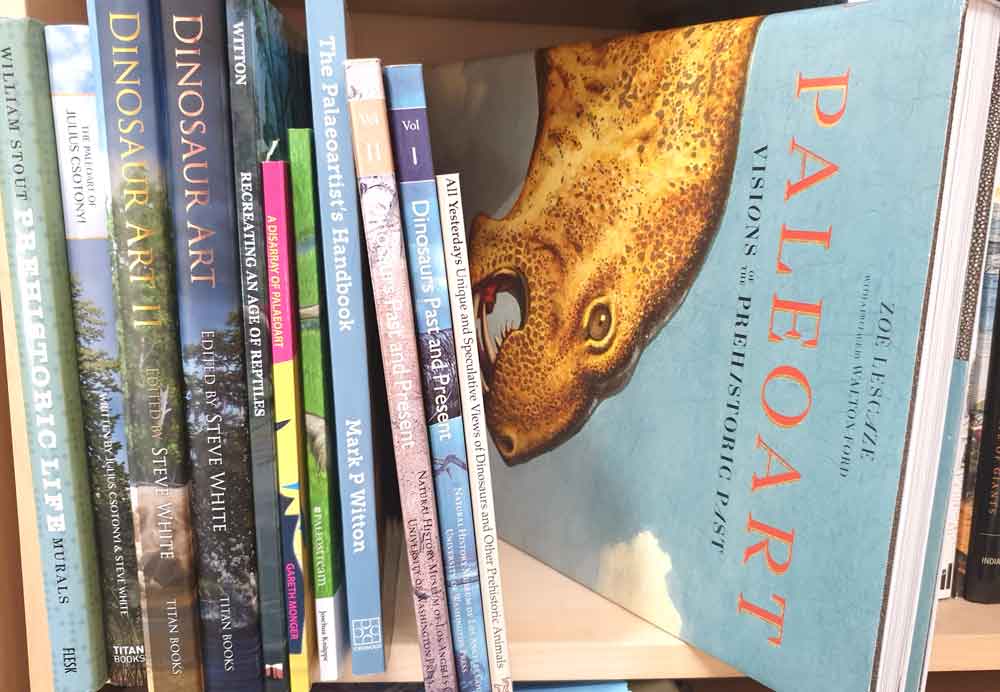

Finally, the third thing I dislike is that great bane of book-buyers from impoverished backgrounds: the price. This book is absurdly expensive; ridiculously so. It’s £69.99 in the UK, $119.95 in the USA (though Amazon is currently selling it at a mere $71.89). As per usual, I appreciate that publishers have to sell books at a given price to cover production costs and to compensate for a sometimes distressingly low number of sales, but I still don’t understand why a slim volume has to cost as much as this one does. Given the price, I fully expected this to be some thick, extremely heavy textbook of perhaps 700 pages or so. But no, it’s a small book of no greater size, production value, academic quality or paper thickness than a great many books half its price or less. I’m extremely pleased to have obtained a review copy but that’s the only way I could ever have obtained it. There is no way I would have purchased it. If a paperback version appears and is reasonably and affordably priced, I apologise for this complaint and may even come back to this review and remove this entire paragraph, but let’s see.

Caption: Senter (2019) is not a big book. Here’s a copy with my hand for scale. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: I was expecting a much, much larger book. Image: Darren Naish.

I apologise for ending on such a downer.

Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs is certainly a unique book, and – as someone familiar with Senter’s writings on the creationist literature – it does have a magnum opus, end-of-the-road feel about it. As I’ve stated in this review, it’s well-written, has very high production values, and is of significant interest to those who follow the esoteric literature on Mesozoic archosaurs, and on the history of religiously motivated pseudoscience. But it has issues.

Senter, P. J. 2019. Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs? The Hilarious History of Creationist Pseudoscience at Its Silliest. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle Upon Tyne. pp. 201. ISBN 978-1-5275-3042-3. Hardback, refs, index. Here at amazon, here at amazon.co.uk, here from the publishers.

A few other reviews of Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs? are online. I deliberately didn’t read them until completing my own review. Having now read them, I see that they make similar points to my own…

Refs - -

Bonnan, M.F. & Senter, P. 2007. Were the basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs Plateosaurus and Massospondylus habitual quadrupeds. Special Papers in Palaeontology 77, 139-155.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Senter, P. 2005. Function in the stunted forelimbs of Mononykus olecranus (Theropoda), a dinosaurian anteater. Paleobiology 31, 373-381.

Senter, P. 2006. Necks for sex: sexual selection as an explanation for sauropod dinosaur neck elongation. Journal of Zoology 271, 45-53.

Senter, P. 2007. A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5, 429-463.

Senter, P. 2009. Voices of the past: a review of Paleozoic and Mesozoic animal sounds. Historical Biology 20, 255-287.

Senter, P. 2017. Fire-breathing dinosaurs? Physics, fossils and functional morphology versus pseudoscience. Skeptical Inquirer 41 (4), 26-33.

Senter, P., Barsbold, R., Brtii, B. B. & Burnham, D. A. 2004. Systematics and evolution of Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History 8, 1-20.

Senter, P. & Parrish, J. M. 2005. Functional analysis of the hands of the theropod dinosaur Chirostenotes pergracilis: evidence for an unusual palaeoecological role. PaleoBios 25, 9-19.

Senter, P. & Robins, J. H. 2005. Range of motion in the forelimb of the theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, and implications for predatory behaviour. Journal of Zoology 266, 307-318.

Sullivan, R. M. & Williamson, T. E. 1999. A new skull of Parasaurolophus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus. New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin 15, 1-52.