I’ve written before about some of the books that had an undue influence on me during my formative years. Such books tend to be well illustrated, they mostly contain attractive, colourful, detailed pieces of art, and they usually showcase weird and surprising proposals and arguments that later proved erroneous, questionable or wrong. The fact that I’ve always considered such books especially interesting and/or influential surely says a lot about me and how my brain works, but whatever.

Caption: the somewhat worn cover of my copy of Watson’s Whales of the World (the 1988 softback edition). Image: Darren Naish.

Today I’d like to discuss another of these fondly remembered books, and if you know it as well as I do you may well understand where I’m coming from. If you don’t know the book at all, (1) what have you been doing with your life?, and (2) obtain the book for yourself, it’s worth it. I’m here to discuss the weird, wonderful Whales of the World (also published as Sea Guide to Whales of the World) by the late Lyall Watson, illustrated by Tom Ritchie, and subtitled ‘A Complete Guide to the World’s Living Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises’ (Watson 1981).

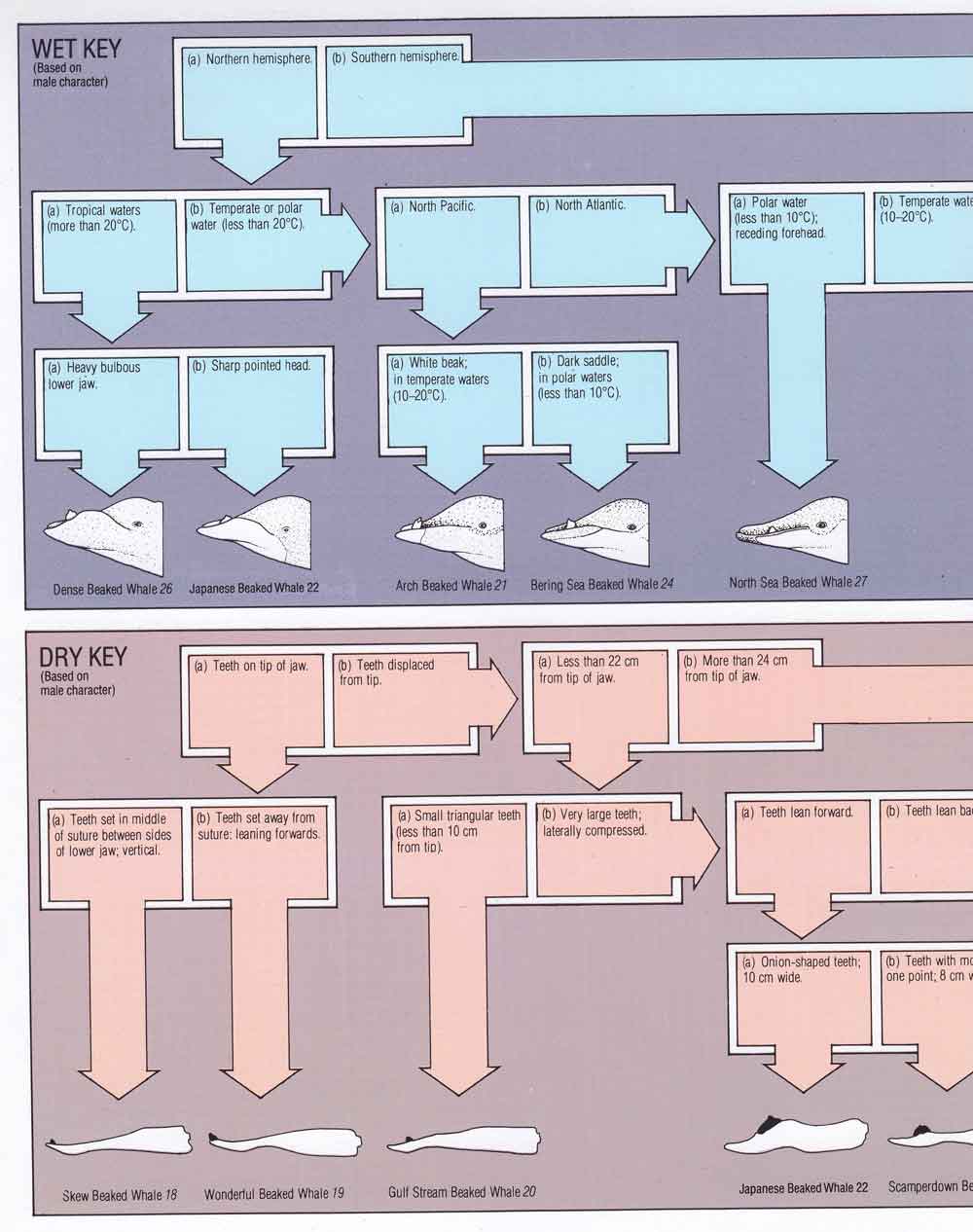

Watson (1981) is a robust, attractively designed volume of 302 pages that goes through all the cetacean species thought valid by the author at the time of writing. It saw at least three reprintings, the first edition being hardback with a dustjacket, the 1985 and 1988 editions being softbacks. The book is arranged taxonomically and groups the cetaceans together by family, each family section including an introduction that has a key and a guide to the family’s respective anatomical traits. The family-level taxonomy Watson used is a little idiosyncratic, on which more later. Each species gets its own two pages. These include a distribution map, colour illustration (sometimes showing variants and juveniles where appropriate), an image of the skull where possible, and text sections on Classification (read: taxonomic history and discovery), Local Names, Description, Stranding, Natural History, Status, Distribution, and Sources (there’s a good bibliography).

Caption: Watson (1981) includes both ‘wet keys’ (providing information on the life appearance of cetaceans, and intended to be used in the field) and ‘dry keys’ (providing information on skeletal material meant to be used to identify stranded animals or carcasses). Image: Watson 1981.

Who was Lyall Watson? Before we move on to the things that make the book unusual, we must ask: who was Lyall Watson? I recall being surprised on first learning of the existence of this book given that Watson was, and still is, best known for his 1973 Supernature: The Natural History of the Supernatural, a book on inexplicable phenomena and how they might be connected and explained. Supernature reads much like woo today, and it’s not surprising that Watson was regarded as embarrassingly credulous and even dishonest by some, and as refreshingly open-minded by others. I knew Watson for these reasons before discovering (by chance, in a bookshop… pre-internet days, kids) that he’d published a book on whales.

Caption: at left: Dr Lyall Watson. At right: 1973’s Supernature, Watson’s most famous book. Images: list of quotations of Lyall Watson (here), goodreads.com (here).

A look at the titles of his more than 20 published works reveals a remarkable and eclectic interest in all of natural history, in sport, culture and ritual (witness the 1989 Sumo: A Guide to Sumo Wrestling), in biology, anatomy and evolution, in the elements and physical geography, in the paranormal and spiritual, and in the human experience and everything about it. Many of us are interested in most or even all of these things, but scarcely any have the skill and knowledge that might allow us to write books on them. In keeping with his diverse interests and writing abilities, he was tremendously qualified, holding degrees in botany, zoology, ecology and anthropology. He even studied palaeontology under the great Raymond Dart. Watson completed his PhD on animal behaviour at the University of London under Desmond Morris, another scientist and author well known for a diverse skillset and ability to write engagingly about remarkable and controversial subjects. Unsurprisingly, Watson moved into the world of TV and also worked as a consultant for zoo and safari park design. Watson died in 2008 and there are some very good obituaries available online.

Anyway, back to the book. What makes it unusual?

Caption: several of Ritchie’s whales, composited together (it might be obvious that I especially like beaked whales). Clockwise from upper left, we’re seeing Fraser’s dolphin Lagenodelphis hosei, Peale’s dolphin Lagenorhynchus australis, Strap-toothed whale Mesoplodon layardii, Rough-toothed dolphin Steno bredanensis and Blainville’s beaked whale M. densirostris; Baird’s beaked whale Berardius bairdii is the big animal in the background. Images: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

Whales of many hues. A key aspect of this book concerns its fantastic artwork. The whales look accurately proportioned and each illustration is nicely detailed. They’re not by Watson, but by artist Tom Ritchie. Watson states in a foreword how he and Ritchie travelled far – both north and south, he says – aboard the MS Lindblad Explorer in search of cetaceans. When describing the field sign, appearance and behaviour of cetaceans, he often describes things from the point of personal experience. Watson also states that he and Ritchie looked at numerous specimens in museum collections and also that they had access to new data never before published: the image of the Vaquita Phocoena sinus – named Gulf porpoise in the book (more on taxonomy in a minute) – “is taken from life and is the first ever printed which shows what the animal looks like” (Watson 1981, p. 8).

Caption: Ritchie’s Vaquita - at top - is apparently the first published full-body depiction of this animal’s life appearance. Below, a photo of a Vaquita in life. Extinction looms for this small cetacean. Images: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981, Paula Olson/NOAA, in public domain (original here).

In view of all this, I find it fascinating that Ritchie’s cetaceans are often more boldly and brightly marked than those illustrated in other works, and depicted in hues that look surprising in view of more typical reconstructions (yes, it might be justifiable to term some depictions of living cetaceans reconstructions, since they’ve been cobbled together from diverse lines of evidence). The classic example is Stejneger’s beaked whale Mesoplodon stejnegeri (termed the Bering Sea beaked whale in the book). Photos and comments on this whale in living state show that it’s greyish brown, pale ventrally, and with off-white around the mouth and eyes. Ritchie’s version is warm brown dorsally, blue on its sides, white ventrally, and with a dark mask across the forehead and eyes (Watson 1981, p. 139). It’s an enhanced, technicolor version of the whale, and so different from other takes on this species that you’re left wondering how accurate it is. This sort of thing occurs throughout the book. The illustrations and wonderful and really attractive, but it’s difficult to be sure that they’re trustworthy.

Caption: Ritchie’s depiction of Stejneger’s beaked whale Mesoplodon stejnegeri. The hues and pattern depicted here are very different from other takes on the appearance of this animal. Image: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

Caption: I once wrote an April Fool’s article whereby a newly designed machine was said to have revealed the true life appearance of whales (it’s here at TetZoo ver 3). The imaginary multi-coloured whales devised for that spoof article were in part inspired by Tom Ritchie’s illustrations. Images: Gareth Monger and Darren Naish.

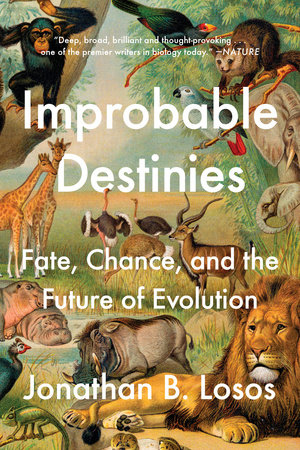

A heterodox phylogeny and taxonomy. A great strength of Watson (1981) is that it includes a fairly decent exposition on cetacean evolutionary history (now very dated of course) and copious discussion throughout of how anatomical characters group species together. What makes the book look odd today, however, is that Watson’s ideas are often heterodox and discordant with consensus views on these issues. We might expect no less of Watson given his other writings, but we might also wonder if the urge to shake things up a bit and promote new or minority opinions was a product of the time in which Watson was working (the late 1970s).

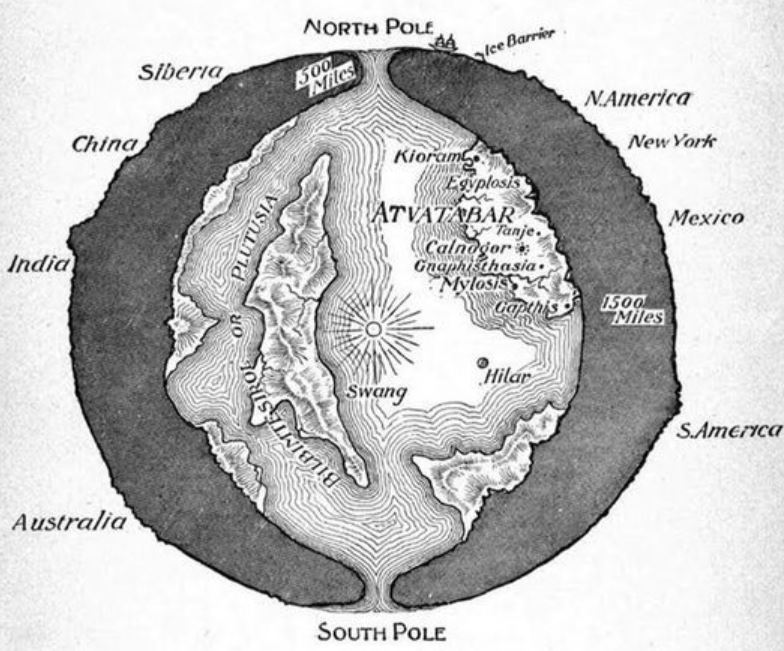

An early section in the book explains how the two great cetacean groups – mysticetes (baleen whales) and odontocetes (or toothed whales) – can’t definitely be said to share a recent common ancestor and might have emerged independently, and it’s even implied that this might also be true of ‘archaeocetes’, the archaic cetaceans otherwise regarded as the ancestors of mysticetes and odontocetes. Cetacean polyphyly is a weird idea in view of how many details mysticetes and odontocetes share to the exclusion of other mammals, but it would have seemed new and exciting during the 1970s given that it had come to the fore in papers of the mid and late 60s (Yablokov 1964, Van Valen 1968). Watson (1981) opted to support it. It isn’t taken seriously today, the anatomical, fossil and molecular evidence supporting cetacean monophyly being overwhelmingly good.

It gets better. Watson (1981) also opted to follow some (otherwise mostly ignored or forgotten) taxonomic proposals for delphinoids, and recognised a distinct Stenidae for ‘coastal dolphins’ (Steno, Sousa and Sotalia) and Globicephalidae for pilot and killer whales and their close kin. Those familiar with the technical literature on delphinoid evolution will know that both names originated elsewhere and have complex histories (which I must avoid discussing here), but their use in a field guide was unusual and heterodox given the tradition of including all of these animals within Delphinidae.

Caption: Watson (1981) wasn’t the only popular volume of the late 20th century to adopt some aspects of ‘non-traditional’ taxonomy. Anthony Martin et al.’s 1990 Whales and Dolphins also includes a globicephalid section (Martin 1990), which opens with this fantastic artwork (by Bruce Pearson). Image: Bruce Pearson/Martin 1990.

I should add that, in other respects, Watson (1981) seems conservative. Caperea is included within Balaenidae, the Kogia whales are included within Physeteridae (rather than their own Kogiidae; in this instance Watson states a preference to stick with consensus) and all river dolphins are lumped into Platanistidae, as was tradition at the time (though he noted that “There ought to perhaps be at least 3 separate families”, p. 148).

Caption: Watson’s Whales of the World includes various montage illustrations like this, which depict the field signs and characteristic markings of groups of species. The pictures look great. However, it has been argued that some of the details shown here are not wholly reliable (read on). Images: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

Smash the patronymy. On the subject of taxonomy – this time on common names rather than scientific ones – another bold move is the assertion that an overhaul is needed in naming conventions, and that biologists and naturalists should absolutely move away from the time-honoured tactic of naming animals after people. After all, calling a given animal – say – ‘Smith’s mouse’ tells you nothing at all about the mouse, does nothing to honour the remarkable features of said mouse, and is positively unhelpful should you see said mouse in the field and wish to remember its name. No, it should be the Epic blue mouse, or the Great spectacled forest mouse, Watson opined. I agree with this idea and also think that names should honour organisms. With this approach in mind, you won’t, then, find True’s beaked whale, Commerson’s dolphin or Bryde’s whale in Watson’s Whales of the World, but the Wonderful beaked whale, Piebald dolphin and Tropical whale, respectively (Watson 1981). Many new names of this sort are proposed in the book.

Caption: close-up of Ritchie’s illustration of Shepherd’s beaked whale Tasmacetus shepherdi, one of my favourite living cetaceans. But it isn’t called Shepherd’s beaked whale in Watson (1981). Instead, it’s the Tasman whale. Image: Tom Ritchie/Watson 1981.

However… language works best when we understand what other people are saying. When a word or name or turn of phrase is established and used throughout a community, it makes sense to stick with it, even if it’s misleading, technically inaccurate, or downright ‘wrong’. We can change it, but – I’d argue – we need to do so democratically, with input from as many relevant players as possible. I suppose a counter-argument is that someone has to get the ball rolling, and that proposing a new set of names in a book designed to function as a fieldguide is a good place to start.

Whatever the argument. Watson’s proposals didn’t win any accolade and his new names never became adopted by the cetological community. Maybe this was because he was an ‘outsider’ and lacked an established reputation as a whale expert or field biologist, but my main feeling is that most workers have wanted to stick with convention and continue to use the names that are otherwise entrenched.

Caption: my own whale illustrations - these were produced for various articles published back in the 1990s - were heavily inspired by those of Tom Ritchie. The originals of these illustrations appear to be lost today, so I have to draw them all anew for my in-prep textbook. Image: Darren Naish.

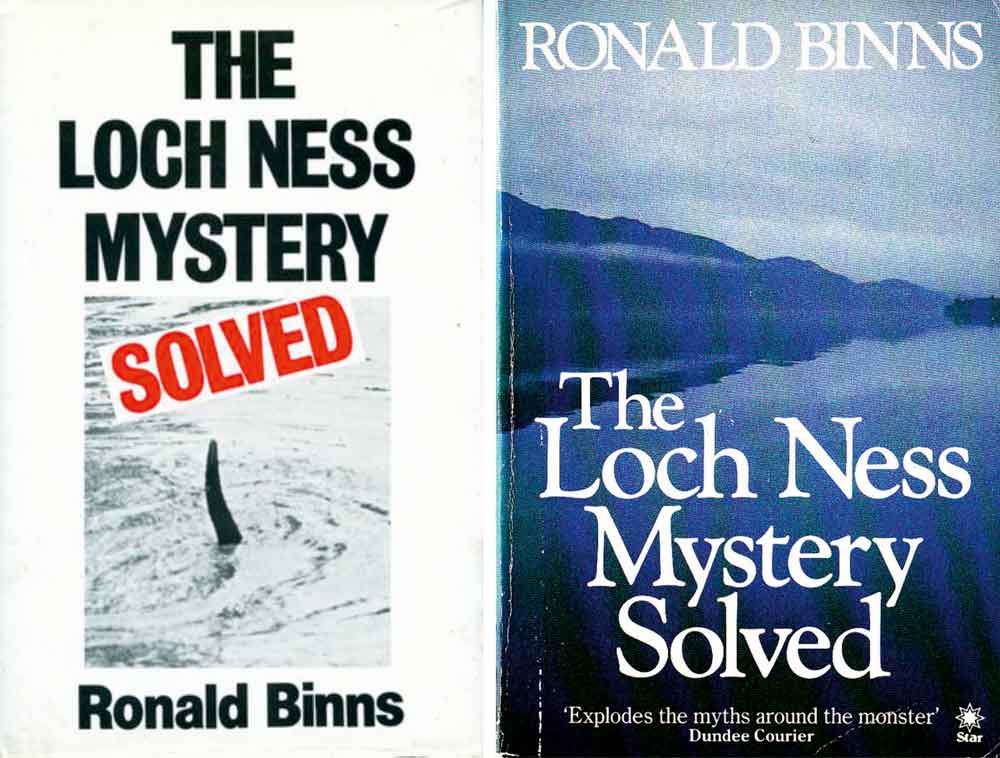

The reception to Whales of the World. Having just noticed that Watson was seen as “an outsider”, it’s worth finishing this article by wondering how Whales of the World was received and perceived by specialists. Among whale researchers in general, the book was mostly ignored and generally regarded as problematic. Typical comments were provided by marine mammal specialist Niger Bonner (who wrote several excellent volumes on pinnipeds and cetaceans himself). Bonner noted that the book had noble aims but was marred by errors and erroneously gave the impression that many of the species were far better known than they really were (Bonner 1983). He criticised the maps, thought that the new naming system was arbitrary, confusing and annoying, and noted that the colours given to the animals in the artwork didn’t always match what was stated in the text (Bonner 1983).

So far as I can tell, these comments were and are typical, and what was – and remains – a popular and much-read book by amateurs and enthusiasts was never endorsed or recommended by those who know whales best.

Caption: of all the popular and semi-technical books on cetaceans and other marine mammals, Watson (1981) remains one of the most interesting and attractive. This photo is from 2015 and I’ve acquired quite a few additional relevant volumes since. Image: Darren Naish.

I’m not a whale specialist, but I love the book, the caveat being – as should be obvious by now – that I love it for its weirdness and its design and artwork, not because I’ve ever found it an indispensable go-to work or a definitive take on the whales of the world. I’d say you should definitely get hold of it if you want a somewhat quirky, exciting take on the subject, or if you’re a completist or want to see Watson’s take on phylogeny, taxonomy and cetacean life appearance.

Cetaceans have been covered at length on TetZoo before - mostly at ver 2 and ver 3 - but these articles are now all but useless since all their images have been removed (and/or they’re paywalled, thanks SciAm). Here are just a few of them…

A 6 ton model, and a baby that puts on 90 kg a day: rorquals part I, October 2006

From cigar to elongated, bloated tadpole: rorquals part II, October 2006

Lunging is expensive, jaws can be noisy, and what’s with the asymmetry? Rorquals part III, October 2006

On identifying a dolphin skull, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Seriously frickin' weird cetacean skulls: Kogia, shark-mouthed horror, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Scaphokogia!, July 2008 (all images now missing)

Cetacean Heresies: How the Chromatic Truthometer Busts the Monochromatic Paradigm, April 2015 (but now lacking all images)

Refs - -

Bonner, N. 1983. [Review of] Sea Guide to Whales of the World. Oryx 17, 49.

Martin, A. R. 1990. Whales and Dolphins. Salamander Books Ltd, London and New York.

Van Valen, L. 1968. Monophyly or diphyly in the origin of whales. Evolution 22, 37-41.

Watson, L. 1981. Whales of the World. Hutchinson, London.

Yablokov, A. V. 1964. Convergence or parallelism in the evolution of cetaceans. Paleontological Journal 1964, 97-106.