Among the most successful of books I’ve been involved in are those devoted to palaeoart. In particular, I’m thinking here of 2022’s Mesozoic Art, edited by Steve White and myself and published by Bloomsbury UK…

Announcing Mesozoic Art, a Lavish New Volume on Modern Palaeoart

The giant, fantastically illustrated new volume Mesozoic Art: Dinosaurs and Other Ancient Animals in Art, edited and written by Steve White and myself and published by Bloomsbury Wildlife, is now on sale…

Reminiscing About Walking With Dinosaurs, Part 1

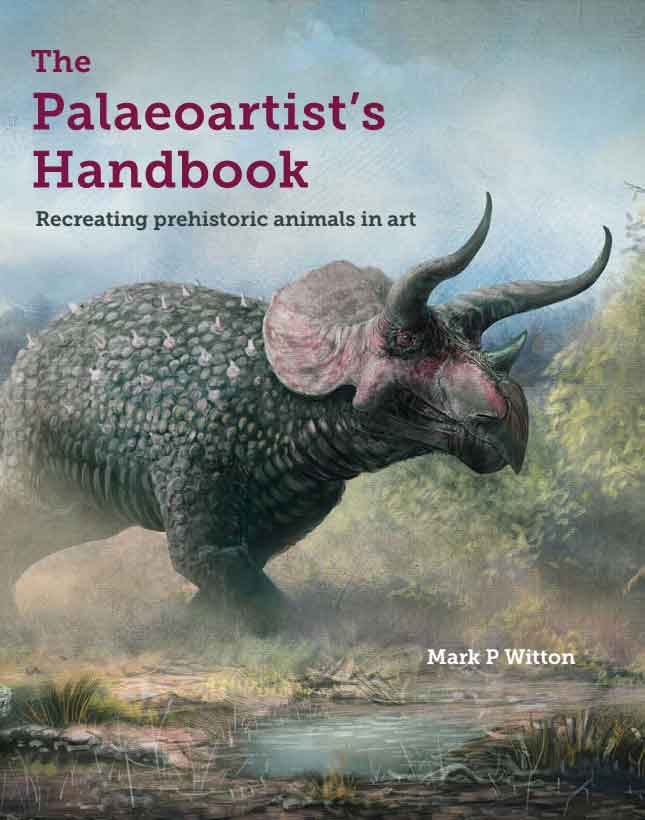

Mark Witton’s The Palaeoartist’s Handbook

It’s probably – no, surely – true to say that palaeoart (aka paleoart) is more popular right now that it ever has been, a fact due in equal part to a vibrant, active community of people worldwide, to the instant, ubiquitous reach of the internet and the connectedness we feel via social media, to self-publishing and on-demand printing services, and to the excitement and discussion generated by what seems to be a never-ending stream of amazing fossil and anatomical discoveries relevant to ancient animals.

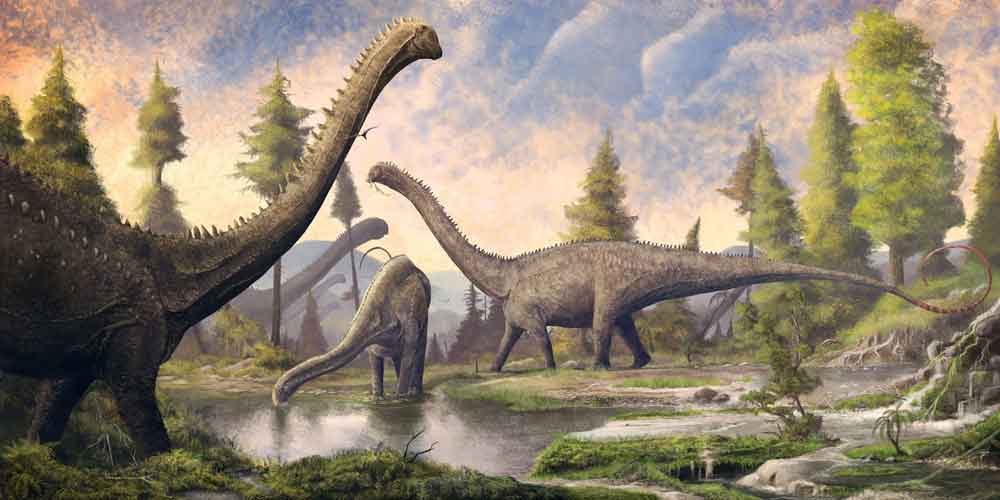

Caption: today, Mark Witton is well known for generating large-scale artworks like this one - depicting the sauropod Diplodocus, and produced to accompanying the NHM’s Dippy specimen as it tours the UK - in addition to work done to accompany press releases. Image: (c) Mark Witton.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Dr Mark P. Witton is, right now, one of the world’s best known and most visible of palaeoartists; his articles and artwork are abundant online, and his work appears in many contemporary published works on prehistoric life, and in various museum installations and other displays. Combine this with the fact that he’s published a long-sought holy grail of the palaeoart canon – a palaeoart handbook – and we surely have one of the most important and worthy palaeoart-themed volumes of all time. Right? Does it deliver?

I refer to 2018’s The Palaeoartist’s Handbook, a slick, extremely affordable softback of 224 pages and extremely high production values. In response to my question above: yes, this book does deliver, and functions extremely well as a ‘handbook’ for those interested in producing palaeoart. Buy it right now if you haven’t done so already. Even those not needing or interested in Dr Witton’s advice should obtain it if they’re interested in palaeoart, since it contains stacks of invaluable review and commentary, does a great job of stating where we are with respect to what we think we know about the appearance of ancient animals, and is really well designed and densely illustrated. It’s probably the most important volume yet published on palaeoart*, and that remains true even if you dislike or disagree with the author’s contentions.

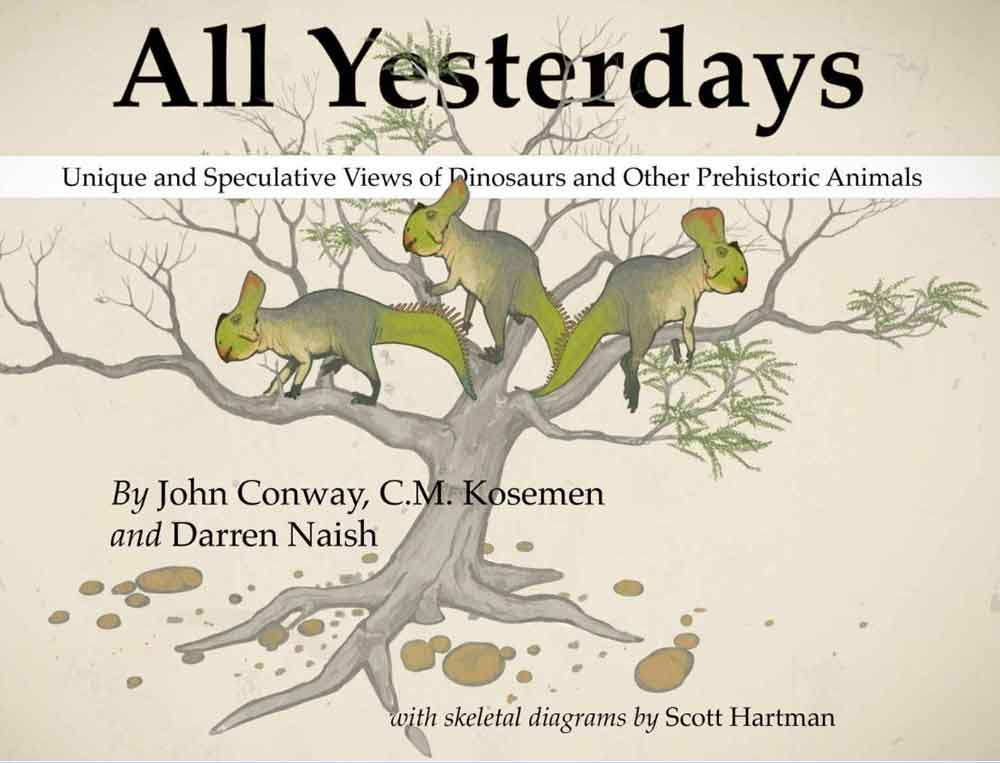

* ‘Importance’ is subjective, but the volume vies – I predict – with 2012’s All Yesterdays and volumes I and II of Dinosaurs Past and Present.

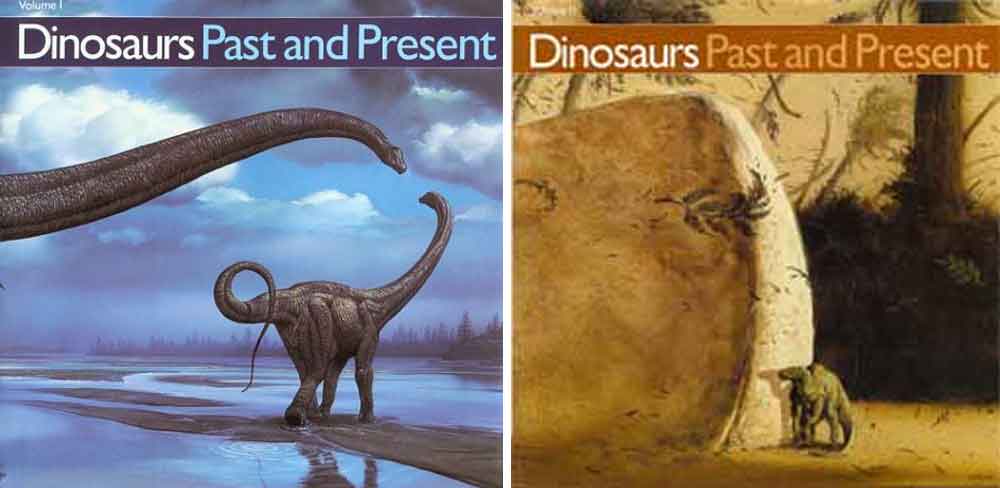

Caption: there aren’t many ‘crucial’/’must have’ volumes on palaeoart, but the Dinosaurs Past and Present volumes are among them, volume II in particular because of Greg Paul’s article (Paul 1987). Images: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press.

A disclaimer I should mention upfront is that Mark and I are long-standing friends and colleagues. I lectured to Mark when he was an undergrad, we’ve been on fieldwork together, and we’ve published several works together on pterosaurs (Witton & Naish 2008, 2015, Dyke et al. 2014, Vremir et al. 2015, Naish & Witton 2017) and palaeoart (Witton et al. 2014). These things might, in theory, mean that I’m positively biased towards his work, but in reality I think they help make me more neutral, since our good relationship means that I can say negative things (where fair and appropriate) and not be worried about being offensive. But let’s see.

Witton (2018) is extremely well designed and very attractive. It’s glossy, full colour throughout, and absolutely packed full of diagrams, photos and art. The art is not just by Mark Witton but also features images by Raven Amos, Rebecca Groom, Johan Egerkrans, Bob Nicholls, John Conway, Emily Willoughby, Julius Csotonyi and Scott Hartman. Holy crap, it’s a virtual who’s who of Early 21st Century palaeoart.

Caption: Witton (2018) includes artwork by several artists, sometimes included to depict diverse styles, compositions and approaches. This is ‘Nemegt Sunrise’ by the amazing Raven Amos (website here), and depicts the oviraptorosaur Conchoraptor with a hermit crab. Image: (c) R. Amos.

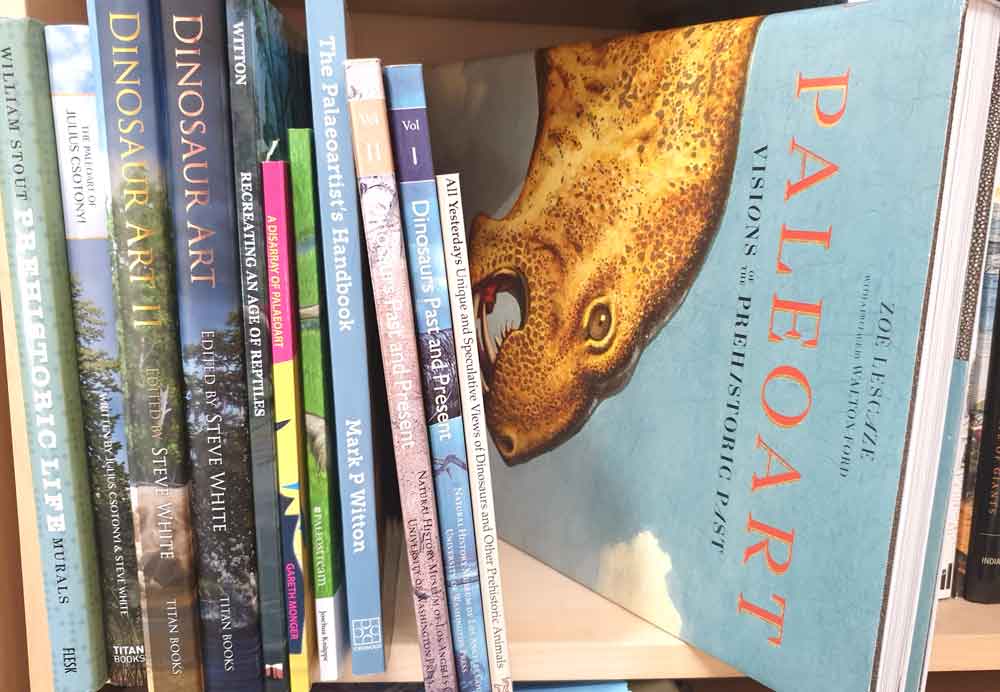

What sort of book is this? A ‘palaeoart book’ can be one of several things. It could be a compendium of historical images (like Zoë Lescaze’s gigantic, deeply idiosyncratic but invaluable 2017 Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past), it could be a bunch of new, daring stuff that makes a point of some sort (cf All Yesterdays), it could be an artist’s porfoilio or a series of portfolios (like the Dinosaur Art volumes, or The Paleoart of Julius Csotonyi), or it could be a technical volume that provides some theoretical or technical background to the field… I’m sure we’re all still waiting for ‘The Grand Handbook to Illustrating Prehistoric Life, a Rigorous How-To Guide’, hint hint.

Caption: the number of books devoted to palaeoart is growing. I think I’ve managed to keep up so far. Image: Darren Naish.

Witton (2018) is partly all of these things: the volume is fundamentally devoted to the techniques, practices and scientific processes and conventions behind the creation of palaeoart, and the case studies and targeted discussions mean that we effectively see much of Witton’s work showcased. But there’s more.

Witton (2018) begins with introductory sections on what palaeoart is and on its history. The historical chapter is quite complete and inclusive, and I’m a big fan of Witton’s take on the work of Cuvier, Hawkins at Crystal Palace and other early efforts. He’s also fair to the artists who produced work during what he terms ‘The Reformation’, some of whom (Greg Paul in particular) have had a major, lasting impact on how we imagine ancient life. The ‘palaeoart meme’ story that I’ve drawn attention to through my own research and the All Yesterdays movement bring a close to this section alongside comments on some of the amazing, exciting new developments being made in the world of soft tissues and palaeo-colour.

Caption: the Crystal Palace animals remain among the most accurate renditions of prehistoric life ever made (like all palaeoartistic reconstructions, they have to be seen as being of their time), and Mark Witton’s take on them is one I absolutely agree with. This photo of the Iguanodon pair was taken in September 2018. Image: Darren Naish.

The meat and potatoes. We then move on to the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the book: a group of chapters that discuss in great detail the process of creating palaeoart. Sections here cover how research is important and how a worker might go about doing it, how knowledge of phylogeny is integral to understanding an organism, and how artists should at least be aware of tropes and stereotypes. This book is fundamentally not a ‘rigorous how-to guide’ to all the prehistoric animals (every time I use this term I’m riffing on the title Greg Paul gave his seminal 1987 article on archosaur reconstruction), but this middle section of the book does include copious discussion of anatomy, the shapes of animals in 3D and cross-section, of musculature and posture, the importance of integument, fat and other external tissue, and so on. I should add that Chapter 9 (‘The Life Appearance of Some Fossil Animal Groups) is devoted to the probable life appearances of key tetrapod groups. Ha, take that fishes.

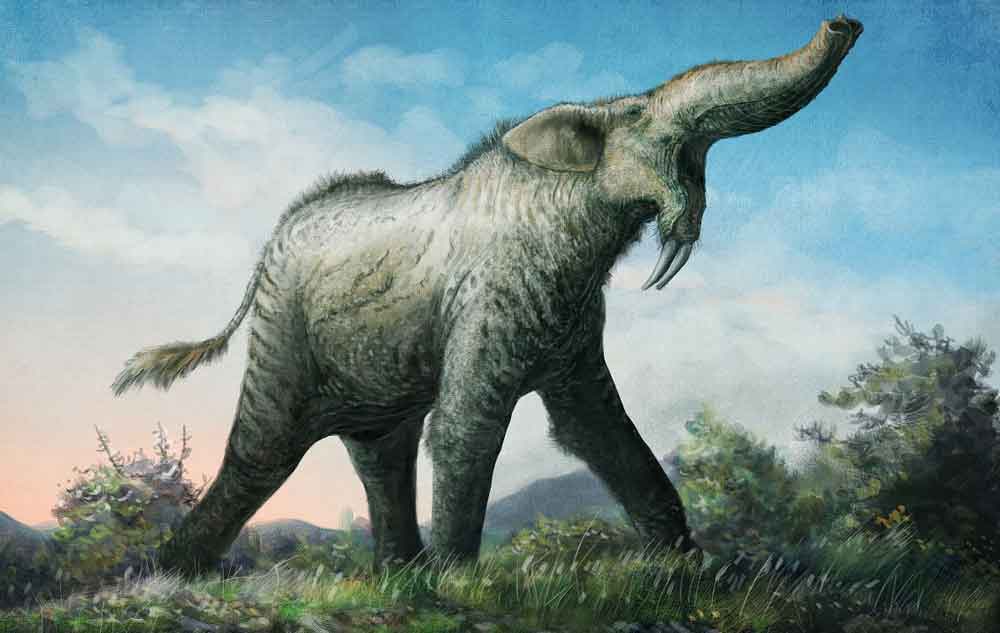

Caption: in many cases, the favoured, traditional look for a given prehistoric animal is not necessarily the one we might favour. Here’s an example: Mark has argued that a new look for the proboscidean Deinotherium - shown here - should be considered. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

These central chapters are probably the most important part of the book and will be those used most by the largest number of people. There’s a ton of information and discussion, and Mark describes in detail how he’s arrived at the conclusions he has. Readers of Mark’s blog will be familiar with some of the arguments here and might also know that much of it has never been properly published (as in, in technical papers or articles). The book is therefore especially significant as a source of primary data, though I know that efforts are underway to get at least some of it into the primary literature.

Caption: extensive sections of Witton (2018) discuss osteological correlates for external texture and other features. In some cases - like ceratopsian dinosaurs - there are many such correlates. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

How confident can we be that Mark is ‘right’ when it comes to his arguments about lips, cornified facial tissue, scalation or fuzziness on the body and so on? I think that a strong response would be that he has at least described, explained and illustrated his reasoning and it’s difficult to think that he’s ‘wrong’, two caveats being that there is – as Mark states quite clearly – still some considerable slop as goes determining the relative size of keratinous coverings (like the pads, scales and sheaths covering horns, claws and so on), and that the vagaries of taphonomy might still be cheating us out of valuable information on which archosaurs had filaments, fuzz or feathers. Yes, I still think that big tyrannosaurs could have been fuzzy and that we aren’t picking this up because the fossils concerned aren’t preserved in the ideal sedimentological regimes.

Speculation and the All Yesterdays Movement. The main message here is that while some speculation always has to be included in palaeoartistic reconstructions, there’s a lot of stuff that’s knowable, or potentially knowable, and informed by actual anatomical data. This is increasingly the case even for colour and pattern (caveat: we still only have data on some infinitesimally tiny percentage of extinct animals). The door is not open for any possibility, and artists who wish to be seen as doing work that’s scientifically credible have to take into account data derived from fossils as well as ‘rules’ (or guidelines) gleaned from living animals. However…

Caption: Conway et al.’s 2012 All Yesterdays has changed the way many people approach palaeoart… but is this for better, or for worse? Image: Conway et al. (2012).

A valid, controversial and timely point concerns just how much speculation is permissible in palaeoart. This is something I feel especially connected to given the impact of my 2012 book – co-authored with John Conway and C. M. Kosemen – All Yesterdays (Conway et al. 2012) and the subsequent ‘All Yesterdays Movement’, which is hated by some but loved by others. Mark’s take on what happened post-AY is that a lot of AY-inspired artwork has failed to appreciate the nuance of the original work, and that AY was (wrongly) taken by some as a green light to go nuts and do whatever, the results being misguided and likely wrong.

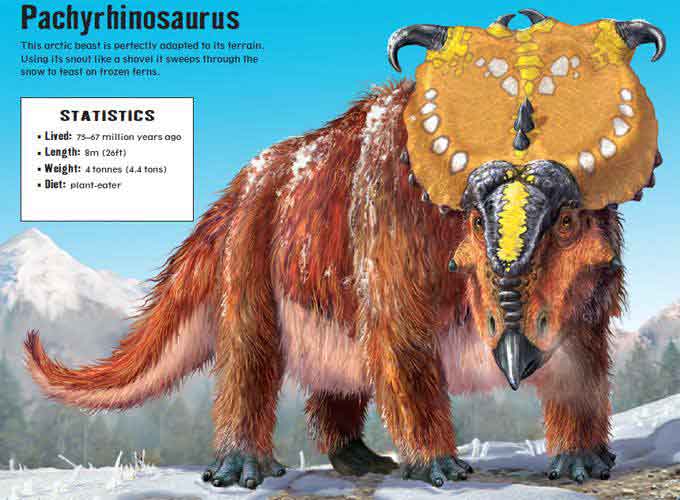

Caption: Mark has indulged in some speculation himself (here: shaggy-coated pachyrhinosaurs), and it’s down to opinion as to whether this is as extreme as anything depicted in All Yesterdays. Image: Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

Caption: it would be wrong to avoid bringing attention to Franco Tempesta’s woolly, cold-adapted pachyrhinosaur, very obviously inspired by Mark Witton’s, and appearing in the 2016 Usborne book Build Your Own DInosaurs Sticker Book. I was consultant, but I’m sure that that’s coincidental. Image: (c) Franco Tempesta/Usborne.

I agree… if we’re talking about artworks that aim to reflect possible realities. A nuance to the nuance of AY is that there exists a small contradiction in the aims of its creators. Yes, we argued that there are many potentially valid, scientifically defensible possibilities that hadn’t or haven’t been sufficiently explored in pre-AY palaeoart, but we did also promote the idea that people might explore other possibilities – even those weird or dumb or wrong – purely for the sake of artistic expression. That this view is canonical in the AYverse is demonstrated by the inclusion in the sequential All Your Yesterdays of retrosaurs that are absolutely contradicted by data but still fun from an artistic take. In other words, not all AY-inspired art is meant to be scientifically defensible. The takehome – post-AY – is that people need to say what they’re aiming to depict: a random fancy or a serious proposal?

Caption: not all AY-inspired art is meant to be scientifically responsible and potentially realistic, some of it is deliberately whimsical and fanciful. Exhibit A: the wonder that is Spinofaaras vulgaris, a creature that now has an internet life of its own. Image: (c) Chris Masna (original here).

Anyway, returning to the contents of Witton (2018), this main section wraps up with some thoughts on how landscapes are created, and how composition and mood can be formed. Discussing environments and landscapes involves science – geology, geomorphology and palaeoclimate, among other things – and this is Witton’s main strength, but I also found his take on composition, stylistic choices and other matters of artistic style compelling…. speaking as someone who lacks artistic training and expertise, that is. The volume ends with a chapter on the professional side of palaeoart.

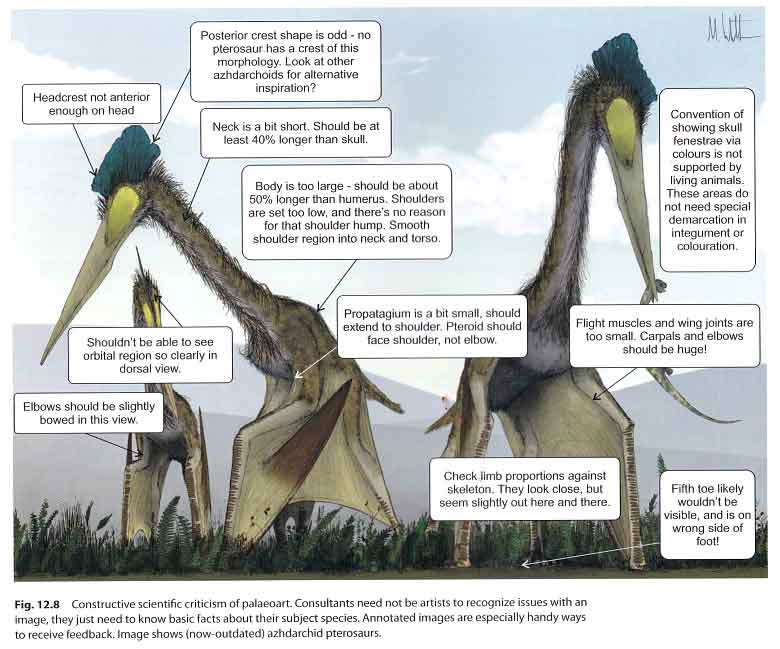

Caption: feedback and criticism is crucial, but it can be difficult to know what to say to artists when you aren’t one yourself. In this section of the book, Mark provides advice, using his 2008 azhdarchid image as a piece that might benefit from constructive criticism. This piece accompanied the Witton & Naish (2008) PLoS paper on azhdarchids. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

On the negative side of things… I find the editing sloppy in places and think that the prose could have been tightened here and there. There are also a few turns of phrase that I found awkward, weird or (sorry) terrible, top of the list being the reference to “palaeontologists with the mightiest beards” (p. 38). On technical aspects, I’m a bit confused by Mark’s use of ‘reptile’ in the old, paraphyletic sense (in a volume otherwise using modern phylogenetic nomenclature, wouldn’t it make sense to use Reptilia for the lizard + turtle + croc clade, and not to use it for a paraphyletic assemblage that excludes birds?). Panoplosaurus is wrongly called an ankylosaurid (p. 125), and isn’t Deinotherium a deinotheriid, not a deinotherid? These are minor, piffling, trivial things that I only state here because I have nowhere else to put them.

Caption: the book is just full of spectacular imagery like this, much of which hasn’t appeared in print before. This image depicts the azhdarchoid pterosaur Thalassodromeus. Image: (c) Mark Witton/Witton (2018).

All in all, The Palaeoartist’s Handbook is an excellent, beautifully produced, well crafted book which contains a wealth of information on the life appearance of extinct animals and how we might imagine them as living things, and it’s phenomenally good on the workings of palaeoart more generally. It should have broader appeal than to the palaeoart fraternity alone, and I think that anyone seriously interested in prehistoric animals or even in the history of art or the way people have imagined the past should obtain it too. For now, Witton (2018) is – mission fulfilled – THE palaeoartist’s handbook indeed.

Mark P. Witton. 2018. The Palaeoartist’s Handbook: Recreating Prehistoric Animals in Art. The Crowood Press, Marlborough (UK), 224 pp, softback, index, refs, ISBN 978-1-78500-461-2. Here on amazon. Here on amazon.co.uk.

For previous TetZoo articles on palaeoart and Wittoniana (the ver 2 and ver 3 ones have been ruined by removal of images), see…

The Great Dinosaur Art Event of 2012, November 2012 (but all images now missing)

All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals - the book and the launch event, December 2012 (but all images now missing)

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014 (but all images now missing)

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

The Natural History Museum at South Kensington, November 2016

Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2016

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 1, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 2, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 3, June 2018

Dinosaurs in the Wild: An Inside View, July 2018

Recollections of Dinosaurs Past and Present, the 1980s Exhibition, February 2019

Refs - -

Paul, G. S. 1987. The science and art of restoring the life appearance of dinosaurs and their relatives - a rigorous how-to guide. In Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present Vol. II. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and London), pp. 4-49.

Recollections of Dinosaurs Past and Present, the 1980s Exhibition

As a regular reader here, you should be familiar with my interest in the portrayal of dinosaur life appearance, and indeed in palaeoart in general….

Caption: a relevant montage, showing (left to right) Charles Knight’s Dryptosaurus painting of 1897 (in public domain); entrance to the exhibition at NHM London (photo by Spike Ekins, used with permission); Allosaurus model by Stephen Czerkas (photo by Darren Naish).

It’s now trite to explain how the iconic, well-drafted, anatomically rigorous illustrations of Robert Bakker, Greg Paul, Mark Hallett and others were integral to the popularisation and dissemination of the ‘dinosaur renaissance’ that occurred between the late 1960s and 1990s, and few interested in prehistoric life will have failed to notice how quickly and frequently reconstructions of extinct species – often good, accurate and innovative – appear today, typically in the digital medium. Palaeoart remains relevant, essential, and with a huge fanbase.

Caption: Robert Bakker’s 1969 sprinting Deinonychus, produced to accompany John Ostrom’s seminal article on this amazing dinosaur. Artistic depictions like this one cement the idea that art has conveyed scientific concepts to the public... but you’ve heard all that before. This is one of several Bakker images included within the exhibition discussed in this article. Image: (c) Robert Bakker.

During the late 1980s and early 90s, a remarkable thing happened. A team at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, assisted by funding from the Natural History Museum Foundation and fronted by guest curator Sylvia J. Czerkas, created a travelling palaeoart exhibition titled Dinosaurs Past and Present. Opening in Los Angeles in February 1986, and accompanied by a symposium that featured talks on dinosaur science and artwork, the exhibition featured a selection of historical illustrations, paintings and sculptures as well as the very best of contemporary work.

Caption: the entrance to what might have been the best palaeoart-themed exhibition of all time, as seen at London’s Natural History Museum in late 1990 and early 1991. A better quality version of this photo will be uploaded to TetZoo in the near future (thanks to Spike Ekins for permission). Image: Spike Ekins.

Accompanying literature does little to shed light on the backstory of the project and how it all came together – maybe this information is out there and I just haven’t seen it – but the final exhibition essentially functioned as a ‘who’s who’ of late 1980s palaeoart. Credits and acknowledgements show that work was loaned from museums and publishers, but overwhelmingly from private collections, mostly those of the artists themselves. This is interesting for several reasons, one being that the curators and organisers clearly had good relations with the artists, another being that the vast majority of iconic 1980s palaeoart was – as of 1986 at least – owned by its creators and not by the sort of wealthy socialites often associated with niche art. Alas poor palaeoart and its lack of reliable patrons (can someone get that printed on a t-shirt please).

After its Los Angeles opening in 1986, the exhibition toured North America, stops including the Smithsonian, the AMNH, the Tyrrell and the Field. It then crossed the Atlantic for showings in Edinburgh, Cardiff and London, where it finished its run in the January of 1991. Sorry, non-English-speaking nations.

Caption: London’s Natural History Museum is an amazing building, decorated inside and out with images of plants and animals. The pterosaur at left is one of several visible on the outside of the museum. Images: Darren Naish.

I didn’t visit London’s Natural History Museum all that often during my teenage years, but I did get to go there several times as special birthday trips. It was on one of these that – in 1990 – I got to see Dinosaurs Past and Present. This was a total accident, by the way, and not due to clever planning. I didn’t even know about the exhibition beforehand, or that it would be on show during my visit.

Two accompanying volumes – edited by Sylvia J. Czerkas and Everett C. Olson – were produced for the exhibition (Czerkas & Olson 1987a, b). They’re must-haves for serious students of palaeoart, containing many articles that provide invaluable background, discussion and commentary. Those by Mark Hallett, Greg Paul and Dale Russell are especially good. They also, it has to be said, contain several articles that are less valuable, are not especially relevant to palaeoart, and could well have appeared elsewhere.

Caption: the covers of volumes I and II of Dinosaurs Past and Present. Both were initially published (in 1987) in hardback, and later (1989) released as softback. My copies are softbacks. Images: Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press.

An introduction by John M. Harris (1987) provides some background to the exhibition and its accompanying symposium. Harris’s article, incidentally, includes that specific statement where ‘reconstruction’ and ‘restoration’ are explained to mean different things (p. 4), so it might be this article – rather than the one by Mark Hallett in the same volume – that is best cited as the origin of this concept.

As one of the few people who (a) is of the right age and (b) writes regularly about palaeoart, I’ve been feeling increasingly duty-bound to discuss my recollections of seeing Dinosaurs Past and Present in London in 1990. What, then, do I remember?

First things first: photos were not allowed. You might like to decide among yourselves whether this is a good thing or not. So, despite having a camera with me (a Canon 35 mm of some sort, I think) I didn’t take any photos, except a few sneaky, illegal shots of Stephen Czerkas’s Allosaurus model. More on that model below.

Caption: here’s the only photo I’ve seen that shows what the exhibition looked like. Behind the Czerkas Allosaurus, framed illustrations on the wall include pieces by Ken Carpenter (at left) and Greg Paul (at right). I can definitely see Paul’s Styracosaurus vs Albertosaurus image. A better quality version of this photo will be uploaded to TetZoo in the near future (thanks to Spike Ekins for permission). Image: Spike Ekins.

As goes the exhibition as a whole, I recall it being in one of the galleries that are perpendicular to the marine reptiles corridor (though I could be wrong). The illustrations were hung on white panelling erected to cover the walls (as confirmed by the photos here, by Spike Ekins), there also being a white partitioning wall, reaching to chest- or shoulder-height, erected along the middle of the gallery. Illustrations were hung from either side of this partition as well. There must have been a shop somewhere, since I distinctly recall the two volumes of Dinosaurs Past and Present being on sale. I was able to buy one of them during my visit (I went for Volume II), eventually obtaining Volume I some years later on a separate trip. I recall these books as being cripplingly expensive and my buying of Volume I consuming essentially all of my Natural History Museum trip budget, so it’s embarrassing now to see how (relatively) inexpensive they actually were.

Caption: my copies of the Dinosaurs Past and Present books still contain their original price labels. Oh, not as expensive as I remembered, then. Whatever. Image: Darren Naish.

Volume I of Dinosaurs Past and Present includes a checklist of all the art featured in the exhibition. No less than 144 pieces were included, the majority being paintings and drawings. They were arranged chronologically, pieces by the likes of Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, Charles Knight and Richard Swan Lull being nearest the entrance and the more contemporary work of Mark Hallett, Ely Kish, William Stout, Greg Paul and so on being encountered later on.

Caption: Charles Knight’s Dryptosaurus painting of 1897 was included in the exhibition and was loaned from the American Museum of Natural History. It’s 58 cm long, 40 cm tall. Image: public domain, wikipedia (original here).

Among the older works, I recall seeing the 1879/1880 ‘Pleasures of Science’ piece by Arthur Lakes, and the Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins depictions of Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus and Megalosaurus. Weirdly, I have no firm recollection of seeing the works of Charles Knight, Rudolph Zallinger or Peter Zallinger, which is distressing given how influential they’ve been.

Caption: Rudolph Zallinger’s incredible mural at Yale’s Peabody Museum is virtually never shown in published photos, and most of the images you’ve seen - like this one - are from the prototype ‘Study’, in which the animals look quite different. Image: (c) Rudolph Zallinger/Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University.

In fact, most of what I remember is decidedly contemporary. Of the Mark Hallett originals on show, I remember the montage images that show representative members of assorted clades. My strongest memory is of the ornithopod group, partly because I recall noticing that a hadrosaur originally meant to be a Tsintaosaurus (and shown with the classic, erroneous ‘unicorn’ crest*) had been ‘corrected’ such that it was now an Edmontosaurus. Hallett’s ‘Iguanodon studies’ is also allotted to memory (perhaps because I always liked his idea that iguanodontian beak tissue might have a serrated, pseudotoothed look), as well as his large Morrison Formation panorama of 1975.

* Tsintaosaurus, it turns out, was neither unicorn-crested, nor flat-headed (as has been argued), but instead equipped with a tall, bulbous crest (Prieto-Márquez & Wagner 2013). No more phallic jokes then.

Caption: Mark Hallett’s ‘Crossing the Flats’ was at the exhibition. It’s a big piece, more than 1.2 m long. Today we don’t think that Mamenchisaurus looked quite like this (Mark was basing his reconstruction on the idea that Mamenchisaurus was a diplodocid). This painting always interested me because of the bipedal, narrow-chord pterosaurs as much as the sauropods. Image: (c) Mark Hallett.

I also recall Ken Carpenter’s illustrations of Sauropelta and ‘Velociraptor’ (proof that Ken was following Greg Paul’s nomenclature; the ‘Velociraptor’ here actually being Deinonychus).

The Greg Paul Years. I make no secret of the fact – it’s mentioned in most books and articles I’ve written or contributed to on dinosaurs and palaeoart (Naish 2009, Conway et al. 2012, Naish & Barrett 2018) – that I consider Greg Paul one of the most influential and important of palaeoartists, and this is true even if you disagree with various of his contentions. Indeed, Greg’s significance in palaeoart is demonstrated by the fact that a full 24 of his pieces were included within the exhibition, more than any other artist.

Caption: Greg Paul’s 1987 article from Dinosaurs Past and Present, Volume II remains one of the best guides to the life appearance of extinct archosaurs, even though it’s now substantially dated. John Conway and I aim to produce a volume that ‘replaces’ it at some point; meanwhile there’s Mark Witton’s excellent The Palaeoartist’s Handbook (which will be reviewed here at TetZoo soon). Image: Darren Naish.

Unsurprisingly, then, my main recollections concern his pieces. His black and white artwork is mostly small (say, 40 x 40 cm or so), numerous corrections and edits being visible where they were made either with paper whitener (we tend to call it tipex in the UK due to one specific brand) or with pieces of card that have been stuck over the relevant areas. I distinctly recall the tail of one of the tyrannosaurs in his ‘Monoclonius albertensis Fending Off Albertosaurus libratus’ (“Monoclonius albertensis” = Styracosaurus) revealing obvious signs of having its angle corrected (a familiar issue to those who’ve drawn dinosaurs). His ‘What Happens When Apatosaurus ajax Seeks Aquatic Refuge from Allosaurus fragilis’ originally had the riverbed too high, a correctional piece of card allowing him to position it further down the canvas, thereby allowing more space for the swimming sauropod’s feet.

I’m pretty sure I also recall looking at his iconic Giraffitan scene, at his G. brancai muscle study, and at the scene showing Iguanodon and Mantellisaurus (I. atherfieldensis at the time) foraging alongside one another.

Caption: Greg Paul’s art is among the most influential dinosaur-themed palaeoart ever produced. Today we know that his feathered non-bird theropods aren’t feathery enough but, hey, you have to start somewhere. This painting was featured in the exhibition. Image (c) Greg Paul.

I also recall a few colour Greg Paul paintings. I definitely remember the ‘Resting Velociraptor antirrhopus Pair’ painting, perhaps in part because Greg’s ideas on feathered dinosaurs, and his taxonomic argument that Deinonychus should be considered a species of Velociraptor (which he’s since abandoned), were novel to me at the time. I think that the Allosaurus vs Diplodocus scene was there but my recollection is hazy. I’m far more confident about seeing Paul’s painting of the Pentaceratops herd. I remember it being pretty big, a metre or so in width. To, again, my disappointment, I have no recollection whatsoever of seeing the ‘Tyrannosaurus torosus in a Fast Run’ (for “Tyrannosaurus torosus” read Daspletosaurus). Shocking, because this is another iconic image of the Dinosaur Renaissance.

Caption: Greg Paul’s running Daspletosaurus - here on the cover of Lauber (1989) - is one of his most famous paintings, yet I don’t remember seeing it. Oh well. Image: Darren Naish.

Enough with the Greg Paul. What else do I remember? I do distinctly remember seeing colour pieces by John Gurche. Gurche has the most incredible style, his colour pieces looking like photos and very often including a marked contrast between a brightly lit, extremely sunny portion and a pitch-black area of deep shadow.

Some of Gurche’s paintings are surprisingly small. On seeing the 1982 Archaeopteryx piece, I was struck by its small size (around 20 x 30 cm). I don’t remember seeing his 1985 Daspletosaurus vs Styracosaurus piece, but it was definitely there. Again, what is wrong with my memory?

Caption: a John Gurche painting of 1985 appeared on the cover of an especially famous and influential book (Bakker 1986). Image: Penguin Books.

On that note: bizarrely, I don’t remember seeing pieces by Doug Henderson, Robert Bakker or Ely Kish, even though they were definitely there too. Weird. Swiss cheese memory. Nor do I remember seeing the original egg tempera study of Zallinger’s Yale mural, Hallett’s ‘Crossing the Flats’, or a hundred other significant pieces that were there. The more I think about this, the angrier I become. Maybe all that drinking and recreational drug use is to blame. Ha ha, kidding, kidding, kidding.

Caption: for its stint at the Royal Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, publicity for Dinosaurs Past and Present included this photo-shoot, involving the late palaeontologist Beverly Halstead and Ron Seguin’s troodontid and dinosauroid models. Halstead is at far right. I don’t know if Halstead is goofing around (he has his arm around the dinosauroid’s shoulders), but it looks like he is. Image: (c) New Scientist.

Finally, what about models? Yes, the dinosauroid and the accompanying Stenonychosaurus were both there, and oh does it hurt to not have any photos of them. You’ve surely seen colour photos of both of these models (created by Ron Seguin in co-operation with Dr Dale Russell): they’re reproduced in many books. Large potted plants (including parlour palms and cycads) were arranged around the models to create a slightly greener vibe. You can see all of this in the black and white photo reproduced above, taken to show the late Beverly Halstead with the models while Dinosaurs Past and Present was on show in Edinburgh.

Caption: one of several books that were highly inspirational if you encountered them at the right time. Wallace (1989) includes both exciting artwork as well as cutting-edge news (Protoavis?! Wtf!, I thought). And on the cover? Yes, it’s Czerkas’s allosaur, portrayed as a dark and sinister predator: “the Darth Vader of animals”, to quote John Conway. Image: Darren Naish.

Nearby, Stephen Czerkas’s half-life-size Allosaurus model was on show. As mentioned above, this is the one exhibit I have photos of (though I can only find one of my photos today, dammit). At half life-size, it stands perhaps 1.5 m at the top of the head. It was browner than I always imagined: based on the cover of Joseph Wallace’s 1989 The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaur* – an influential book for the young Darren Naish – I always thought it was dark grey or black. Like all of Czerkas’s models, it included a spectacular and really impressive amount of detail and was a joy to look at.

* I find it a bit annoying that Steve Brusatte’s new book has essentially the same title. Steve didn’t know of Wallace’s book until I told him about it, so not his fault. Did no-one think to say anything?

Caption: Stephen Czerkas’s brilliant Allosaurus model at the Natural History Museum, London (as demonstrated by the accompanying stonework) in 1990. Note that the model is in a different position relative to where it is in Spike’s photos shown above. Image: Darren Naish.

Several smaller models, made by Stephen and his wife Sylvia Czerkas, were also on show and on top of white, rectangular display stands. I remember Sylvia’s hatching Protoceratops and, I think, Stephen’s 1986 Stegosaurus, controversially constructed with the single row of plates that Stephen thought correct (Czerkas 1987).

For completist reasons I should note that I did get to meet Stephen, once, at the Denver 1999 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting. We spoke briefly about ‘Archaeoraptor’, later unveiled as a composite but thought by Czerkas at the time to be a long-tailed early bird, but I never did get to talk to him about his art.

Anyway, that about wraps things up. Clearly, my memory of a truly momentous and significant exhibition is alarmingly deficient, and the fact that I don’t really have any photographic record of what I saw just makes it worse. What I do remember was, however, thrilling. There have, of course, been a good number of palaeoart-themed exhibitions since 1991, but I think it’s fair to say that none have been as grand, culturally significant or momentous as Dinosaurs Past and Present. Could its like ever occur again? Maybe time will tell, or maybe I’m nostalgic for a Golden Age which has long since passed.

Caption: what has happened in the world of palaeoart since the days of Dinosaurs Past and Present? Quite a lot… Image: Darren Naish.

Palaeoart and changing ideas on the life appearance of Mesozoic dinosaurs have been covered at TetZoo many times over the years. Many of the older articles are now useless because malfunction at the hosting sites has removed their illustrations. Anyway, see…

The Great Dinosaur Art Event of 2012, November 2012 (but all images now missing)

All Yesterdays: Unique and Speculative Views of Dinosaurs and Other Prehistoric Animals - the book and the launch event, December 2012 (but all images now missing)

Artistic Depictions of Dinosaurs Have Undergone Two Revolutions, September 2014 (but all images now missing)

The Dinosaurs of Crystal Palace: Among the Most Accurate Renditions of Prehistoric Life Ever Made, August 2016

The Natural History Museum at South Kensington, November 2016

Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2016

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 1, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 2, June 2018

25 Years after Jurassic Park, Part 3, June 2018

Dinosaurs in the Wild: An Inside View, July 2018

Refs - -

Bakker, R. T. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. Penguin Books, London.

Czerkas, S. A. 1987. A reevaluation of the plate arrangement on Stegosaurus stenops. In Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present, Volume II. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and Washington), pp. 82-99.

Harris, J. M. 1987. Introduction. In Czerkas, S. J. & Olson, E. C. (eds) Dinosaurs Past and Present, Volume I. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County/University of Washington Press (Seattle and Washington), pp. 1-6.

Lauber, P. 1989. The News About Dinosaurs. Bradbury Press, New York.

Wallace, J. 1989. The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaur. David & Charles, Newton Abbot, London.