Time for more Spec Zoo at Tet Zoo!

The Tet Zoo Guide to the Creatures of Avatar, Updated for 2022

Humanoid Dinosaurs Revisited Again: Russell and Séguin’s Dinosauroid at (Nearly) 40 Years Old

Dougal Dixon’s After Man, the Initial Pitch Document

There can’t be many visitors here who are unaware of Dougal Dixon and his 1981 book After Man (Dixon 1981), the work which effectively started the entire Speculative Zoology (or SpecZoo) movement.

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 3): the Dinosauroid and its Chums

Welcome to another article on alternative timeline dinosaurs.

Caption: what’s this? It’s an unfinished sculpt of the head of Paranthropoharpax, by Mette Aumala. Read on for more. Image: (c) Mette Aumala.

The previous two articles looked at recent and current ideas on those non-bird dinosaurs that might have evolved in alternative timelines where the end-Cretaceous extinction event never happened, and where the modern world is occupied by the descendants of groups that otherwise went extinct about 66 million years ago. You can see those articles here and here. And the most recent of those two articles looked at the ‘would there be humans anyway?’ argument, always a mainstay of alternative timeline dinosaur discussion.

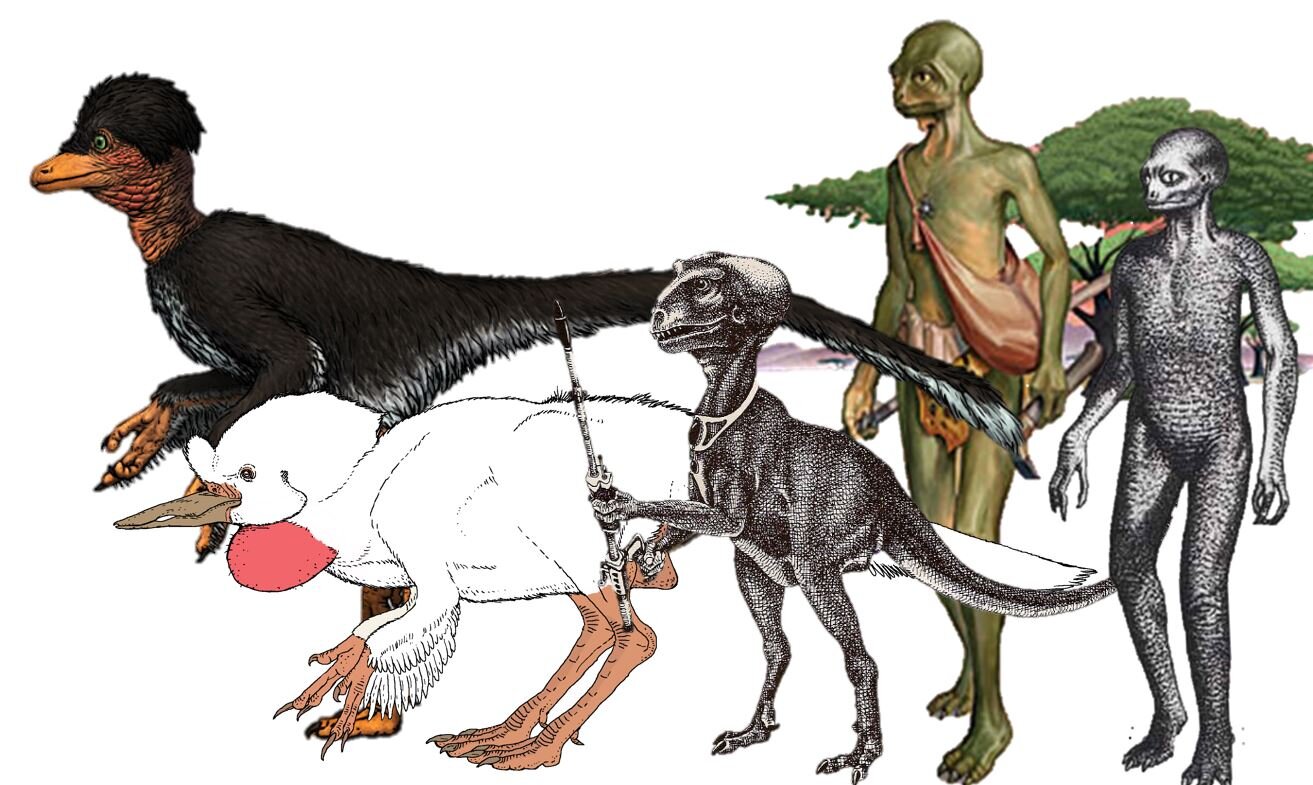

Caption: a whole bunch of dinosauroids, variously by (left to right) Mette Aumala, C. M. Kösemen, John McLoughlin, Matt Collins, John Sibbick.

The other big question that everyone asks about post-Cretaceous, alternative timeline dinosaurs is also about the evolution of intelligence, but this time of a non-human sort. If non-bird dinosaurs didn’t go extinct, surely they’d give rise to animals of primate-like, if not human-like, intelligence… right? The ‘intelligent dinosaur’ meme has been covered quite a bit here on TetZoo before (see links below), the problem as always being that my older articles on this subject are today plagued by hosting issues. For this reason I’ve linked below to the wayback machine versions of the articles concerned.

Caption: if you’ve ever opened a post-1980s dinosaur book, chances are high that you’ve seen photos of Dale Russell and Ron Séguin’s troodontid and dinosauroid models. This is the commonest set of images, as reproduced in Russell (1987, 1989) and other sources.

Conversations about big-brained dinosaurs invariably revolve – as well they should – around Dale Russell’s ‘dinosauroid’ of the 1980s, an imaginary humanoid theropod which Russell posited as a possible evolutionary descendant of troodontid theropods had they continued to evolve beyond the end of the Cretaceous. I’m keen to avoid saying too much about the dinosauroid here for fear of repeating content, but it’s worth noting that Russell’s vision of the dinosauroid was more fleshed out and detailed than many assume, and that its anatomy was more complex and nuanced than might first appear (Russell & Séguin 1982). Anyway, please read the older TetZoo articles if you want to dig deeper.

Caption: a rare photo of Dale Russell (at left) and Ron Séguin in the company of the dinosauroid; this photo belongs to the archives of the Canadian Museum of Nature and was shared in September 2019 by Jordan Mallon. Image: (c) CMN.

The dinosauroid’s infamy was and is due to the construction of an amazingly good life-sized model by sculptor Ron Séguin, who collaborated with Russell on the project (Russell & Séguin 1982). I saw the model in person in 1990 when it came to the UK for the Dinosaurs Past & Present exhibition, but failed to take the illegal photos I now so wish I had. You can read about my recollections of that amazing exhibition here (and be sure to read the comments).

Caption: Ely Kish’s dinosauroid models, used as the basis for a large painting which she finished; it remains in storage and has never seen print. These images were shared on Michael Ryan’s blog (here). Images: (c) Michael Ryan.

Séguin’s construction is well known, but a revelation new(ish) to some of us is that the late Ely Kish – another artist who collaborated with Russell (Russell 1987, 1989) – produced several amazing pieces of art that depict dinosauroids in assorted novel settings. One (a clay sculpture) shows a parent playing with a baby-faced youngster, and another – a large painting – shows a 1980s-era dinosauroid drawing attention to a reconstruction of an artistic scene. That scene is a piece of palaeoart, produced by the dinosauroids, and depicting their own kind during its cave-dwelling, ‘Palaeolithic’ phase of evolution. To my knowledge, the painting has never been published, perhaps because Dale Russell gave up on any dinosauroid-themed projects following the negative response the idea received after appearing in print during the early 80s. It was apparently produced for Russell’s 1989 book An Odyssey in Time: the Dinosaurs of North America (Russell 1989) but eventually excluded.

Caption: some post-Russell versions of the dinosauroid. At far left: a life-sized model on display at Dorchester’s Dinosaur Museum; at centre, two views of the suit made by Peter Minister for the 1991 TV series Dinosaur!; at far right, John Sibbick’s take on the dinosauroid, from David Norman’s 1985 book The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Images: Jim Limwood, CC BY 2.0 (original here), Norman (1991), John Sibbick/Norman (1985).

The dinosauroid has proved such a mainstay of post-1980s dinosaur pop-culture that it’s mentioned and discussed in a vast number of popular books on dinosaurs and prehistoric life, and has often been redrawn (often incorrectly); models and even suits worn by actors have been constructed too. One day I should compile a bibliography. And dinosauroid-like animals have been invented by several writers and authors beyond Dale Russell, among them John McLoughlin’s big-brained dromaeosaur (McLoughlin 1984), Magee’s Anthroposaurus (Magee 1993), the hadrosaurian Voth of Star Trek: Voyager, and Mette Aumala’s Paranthropoharpax naishi.

Caption: at left, John McLoughlin’s dinosauroid (which I opted to name Bioparaptor). At right: the cover of Magee’s unusual book on big-brained dinosaurs (which Amazon now values at about £200). Images: McLoughlin 1984, Magee 1993.

I still say that the dinosauroid sucks. Its entire look is dependent on the idea that the human shape is the ‘best’ one for an intelligent, big-brained animal, an idea that Russell appears to find palatable if not preferable (Russell 1987, p. 130; Psihoyos & Knoebber 1994, p. 252). But this doesn’t mean that the entire concept of big-brained smart dinosaurs is a bad one. As has now been said many times, birds (parrots and corvids, at least) overlap with primates in relative brain size and cognitive abilities, meaning not only that big-brained smart dinosaurs evolved for real in our own timeline, but also that it could happen again in a timeline where other bird-like lineages exist.

And if big-brained, smart non-bird theropods really evolved, they would – I think – more likely be shaped like birds and other theropods: not erect-bodied and humanoid, but horizontal-bodied, feathery, and with the long-snouted faces and inward-facing, clawed hands more typical of the group. This argument is old hat now since it got a lot of coverage back in 2006 when C. M. Kösemen (aka Memo) – inspired, I think, by my writings on alternative timeline smart dinosaurs – invented Avisapiens saurotheos.

Caption: for a change, I’m not going to share Memo’s Avisapiens (well, it’s already visible in the montage at top), but Mette Aumala’s Paranthropoharpax naishi. For an article on this creature go here. Mette has recently been working on a CG portraits of this species (go here on Twitter). Image (c) Mette Aumala.

In the years since 2006, Memo has invented additional big-brained hypothetical dinosaurs and – via collaboration with Simon Roy – has devised a parallel world where big-brained dinosaurs of more than one species possess their own culture, technology and art, and are depicted alongside beasts of burden and other contemporaries. Post-2006, we’ve also seen the coming and going of the 2007 kid’s TV series Dinosapien, the appearance of some surprisingly pro-dinosauroid commentary from Richard Dawkins (I wrote about that event here), and the coverage of the dinosauroid in numerous articles and books (e.g., Hecht 2007, Naish 2008, Socha 2008, Switek 2010, Losos 2017).

Caption: screengrabs of pages from two recent-ish articles discussing the dinosauroid: Hecht (2008) and Socha (2008).

And the big-brained dinosaur trope continues to raise its head in the popular and semi-technical sphere, often from people who seemingly aren’t aware of Russell’s dinosauroid and appear to be discovering it for the first time. The increasing popularity of ideas about humanoid reptilian aliens and a cryptic elite of shape-shifting lizard-people (good work, David Icke) mean that people whose idea of research starts and ends with Google are discovering dinosauroids and somehow working them into a world view that involves the Illuminati and high-level One World Government conspiracies. In short, it’s an idea that isn’t going away, and Jonathan Losos was right in saying that “… to my surprise … The dinosauroid hypothesis was alive and thriving in cyberspace” (Losos 2017, p. 323).

And that, effectively, brings us up to date…. for now. What might happen next in the world of Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs?

For previous TetZoo articles on alternative timeline dinosaurs and related issues of SpecZoo, see…

Dinosauroids revisited, November 2006

Dinosauroid cave art discovered, March 2007

How intelligent dinosaurs conquered the world, March 2008

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Belatedly, Nemoramjetia (= Avisapiens), November 2008

Richard Dawkins and the crappy 'humanoid dinosaurs' that just won't die, November 2009

Dinosauroids revisited, revisited, October 2012

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, June 2018

Could We Domesticate (Non-Bird) Dinosaurs?, August 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

TetZoo Bookshelf, February 2019, Part 1, February 2019

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 1), December 2019

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 2), December 2019

Refs - -

Hecht, J. 2007. Smartasaurus. Cosmos 15, 40-41.

McLoughlin, J. 1984. Evolutionary bioparanoia. Animal Kingdom April/May 1984, 24-30.

Naish, D. 2008. Intelligent dinosaurs. Fortean Times 239, 52-53.

Norman, D. 1991. Dinosaur! Boxtree, London.

Psihoyos, L. & Knoebber, J. 1994. Hunting Dinosaurs. Cassell, London.

Russell, D.A. & Séguin, R. 1982. Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid. Syllogeus 37, 1-43.

Socha, V. 2008. Dinosauři: hlupáci, nebo géniové? Svĕt 3/2008, 14-16.

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 2)

In the previous article we looked at alternative timeline dinosaurs, and in particular at Dougal Dixon’s The New Dinosaurs, at the Speculative Dinosaur project, and at a few things that connect these two endeavours.

We finished that article by introducing an idea mentioned or discussed several times in discussions about SpecZoo: given that mammal evolution would surely continue in a dinosaur-dominated, post-Cretaceous world, could big-bodied mammals evolve, and could they give rise to humans... or, at least, to human-like primates?

Before I continue, I should add that this issue is especially topical at the time of writing (early December 2019) since a BBC World Service radio programme featuring this very issue has just appeared. It’s part of the CrowdScience series, is titled ‘Would humans exist if dinosaurs were still alive?’ and can be found here. It features me, Memo Kosemen, Elsa Panciroli, Anjali Goswami and Nicola Clayton.

Caption: a whole radio show on speculative dinosaurs! You need a BBC account to access it. Image: BBC (from here).

Could there be humans? Well, this would require the (mostly) terrestrial evolution of a big-bodied primate group, and I said in the previous article (where I called it the no megamammals rule) that that might not be possible in a dinosaur-dominated world (and I mean because dinosaurs and other archosaur groups were filling up the available niche space, not because predatory species were perpetual eliminators of animals that dared set foot on the ground or anything like that). Could, then, we have hypothetical ‘human-level’ apes (thinking here of cultural and technological sophistication, and/or relative intelligence) evolve in an arboreal setting?

Here it’s worth saying that the existence of hypothetical climbing and flying predatory archosaurs might not be an evolutionary obstacle to the existence of relatively big arboreal mammals. I say this because large, scansorial and arboreal mammals have already evolved in a world where they’re predated upon by large, predatory flying theropods, some of which can reach into cavities with flexible legs and feet, or pull relatively big prey items (like sloths and big monkeys) from treetops and branches.

But… if I let my archosaur bias run away with me, I might propose that the existence of arboreal mammals in a dinosaur-dominated world could encourage the evolution of specialised scansorial or arboreal archosaurs (presumably theropods) that have somehow influenced primate evolution, and ultimately derailed any potential evolution of proto-humans. I like this idea, and it isn’t entirely without precedent in our own timeline, since it’s been formally suggested that the predation pressure exerted upon primates by large predatory reptiles – snakes, specifically – has indeed shaped primate evolution (Isbell 2006).

Caption: a speculative arboreal maniraptoran from an alternative timeline. It runs and leaps about in tropical tree-tops, has extremely powerful, prehensile feet, and predates on primate-like mammals. Image: Darren Naish.

Here’s another possibility: could human-like apes evolve on an island refugium where archosaurs weren’t dominant? The idea that ‘unusual’ animals can evolve and persist on islands is already a mainstay of island biogeography theory and verified by many real-world examples. A dinosaur-dominated post-Cretaceous world must be allowed to include similar diversity, and maybe this is where you find your big, atypical mammals (and perhaps big tortoises, arthropods and whatever else).

Could human-like primates evolve on islands? Well, this would require that your ancestral primates occurred in such places in the first place, and that the relevant selection pressures would have led to the evolution of human-like animals. While this isn’t impossible, it seems unlikely: there are good reasons for thinking that the ecological conditions specific to certain regions of Neogene continental Africa are what ultimately resulted in the emergence of hominins and hence humans (Kingdon 2003). My conclusion here is that an alternative evolutionary pathway for primates doesn’t give you humans as one of its ‘products’.

Finally, if we have an alternative timeline where apes evolve, is it conceivable that human-like primates, and, ultimately, alternative timeline humans, evolve anyway, dinosaurs or not? After all, humans and human ancestors spent their entire history living alongside formidable predators and competitors which either had to be avoided, defeated or out-smarted, and we might argue that the technological and other behavioural sophistications of hominids could make them exempt from the ‘no megamammal rule’ introduced above. The result would be what I’m going to call a Flintstones Universe.

Caption: non-bird dinosaurs and humans live alongside one another in the episode In Dino Veritas (season 2, ep 7) of the TV series Sliders, which aired in April 1996.

As appealing as this model might be for the purposes of human-oriented drama and adventure (it’s been done before, in Sliders - a TV series about travel between alternative timeline versions of Earth - and I’m sure elsewhere), I’m worried, since it also sounds a lot like the ‘inevitable humans’ model promoted by those who seem to regard humans as The Best Animals. Some of you might have seen the 2010 episode of the BBC TV series Horizon (it’s here) where Simon Conway Morris – who’s well known, these days, as something of an opponent to the late Stephen Jay Gould’s argument that nothing in evolution is inevitable and that events wouldn’t have run the way they did if we were to “replay life’s tape”* (Gould 1990, p. 48) – proposed both that humans could well have evolved in a dinosaur-dominated world and that smart humanoid dinosaurs could well have evolved as well. Even better, Conway Morris suggests in the same TV show that humans and big-brained dinosaurs could have forged an alliance. True, true, symbiosis is not uncommon in the living world – ants and aphids, cleaner fishes and big reef fishes, Godzilla and Mothra – but the real-world history of humans shows either that we smashed competitors into bloody fragments or absorbed them into our collective via sexy, sexy ways. The latter option is unlikely to play out in a world where humans and humanoid dinosaurs live together, but the former suggests a less than happy outcome for one of the players.

Caption: some of the key books relevant to the discussion here.

So, excuse me if I’m a little sceptical of any proposed human-dinosauroid buddy-flick partnership. And am I sceptical of the idea that hominids, hominines and hominins were indeed exempt of the ‘no megamammals rule’? Yes. Incidentally, Conway Morris’s inevitability vs Gould’s contingency formed the subject of a long-running dispute: Riley Black wrote about this discussion here.

* Does this analogy still work given that hardly anyone uses recording tape anymore?

Caption: Simon Conway Morris talks about the evolution of intelligence while a dinosauroid reads a newspaper in the background. This is a screengrab from the 2007 episode of BBC Horizon titled My Pet Dinosaur.

Other, more recent alternative timeline dinosaur thoughts. As should be clear from this article and its predecessor, interest in alternative timeline dinosaurs is at an all-time high. The current resurgence of monster movies that feature King Kong, Godzilla and the like also means that such creatures have appeared in big-budget, mainstream movies. Peter Jackson’s 2005 movie King Kong featured several post-Cretaceous dinosaurs (among them Vastatosaurus rex, Brontosaurus baxteri and Venatosaurus saevidicus), the design and backstory of which makes at least some sense on the basis of things that happened in the real timeline… though the idea of a dinosaur genus persisting relatively unchanged for 150 million years or so can’t be considered sensible in view of what we know.

Caption: I don’t especially like the dinosaurs of Jackson’s King Kong (they’re too conservative), but a lot of the artwork is neat. This concept art depicts Vastatosaurus rex, a giant Holocene tyrannosaurid that evolved from Tyrannosaurus. Image: The World of Kong (here).

Pixar’s 2015 The Good Dinosaur also has to be mentioned, but I wish it didn’t because I think it’s a terrible film and an abhorrent waste of an opportunity. It’s supposed to be an alternative timeline movie but instead it just seems like a Flintstones reboot without the Flintstones.

Caption: opening spread from Pickrell (2017), art by James Gilleard. Some of the creatures here are based on those of TND and the Speculative Dinosaur Project. Image: BBC Focus magazine.

A 2017 article by John Pickrell is one of the newest published pieces on alternative timeline dinosaurs, and it’s well worth tracking down for those seriously interested in this stuff (Pickrell 2017: there’s an online version here which includes some extra stuff relative to the printed one). It features some fairly outré artwork (by James Gilleard; it’s not included in the online version) depicting creatures inspired by those of The New Dinosaurs, and include quotes from Steve Brusatte, Tom Holtz, Andrew Farke, Matthew Bonnan and Victoria Arbour (and Paul Barrett and me, but in the online version only) (Pickrell 2017).

Caption: the Gourmand Ganeosaurus tardus, a carrion-feeding tyrannosaur whose ancestors migrated to South America during an alt-timeline version of the Great American Biotic Interchange. I’ve never been able to figure out what it’s eating. Image: art by Steve Holden, from Dixon (1988).

A few interesting, specific speculations are made in John’s article. Tom notes that the Gourmand of TND is maybe not so ridiculous given recent discoveries concerning abelisaurs (rather than tyrannosaurs), Matthew suggests that arboreal (non-bird) dinosaurs might have co-evolved with flowering plants, and Victoria proposes that the neornithine bird radiation might not have been as bushy and explosive if pterosaurs had never died out (Pickrell 2017). Other ideas mooted in the article are that climbing, monkey-like theropods might evolve, and that there might be shaggy-coated Arctic specialists, speedy grassland herbivores and whale-like descendants of spinosaurs; in part, they’re seemingly inspired by the Dixonian creatures of TND.

Caption: more art from Pickrell (2017), by James Gilleard. Image: BBC Focus magazine.

The online version of the article includes comments on some of the events of post-Cretaceous times that – if they happened in an alternative timeline – would likely have some impact on the evolution of dinosaurs, pterosaurs and so on. Examples: what would the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum mean for dinosaurs, how might dinosaurs and pterosaurs respond to the cooling and drying of the Miocene, the spread of grasslands and so on, and what might happen in the cool, dry conditions of the Pleistocene? There’s vast scope for speculation here and even for some actual science, since we have enough data to show that organisms evolve in predictable directions when faced with increasing or decreasing temperatures and other such changes.

It's at this point that I have to stop – but there’s more to come. The next article (last in this series) covers ‘dinosauroids’ and other hypothetical big-brained dinosaurs.

For previous TetZoo articles on alternative timeline dinosaurs and related issues of SpecZoo, see…

Dinosauroids revisited, November 2006

Dinosauroid cave art discovered, March 2007

How intelligent dinosaurs conquered the world, March 2008

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Belatedly, Nemoramjetia (= Avisapiens), November 2008

Richard Dawkins and the crappy 'humanoid dinosaurs' that just won't die, November 2009

Dinosauroids revisited, revisited, October 2012

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, June 2018

Could We Domesticate (Non-Bird) Dinosaurs?, August 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

TetZoo Bookshelf, February 2019, Part 1, February 2019

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 1), December 2019

Refs - -

Dixon, D. 1988. The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution. Salem House Publishers, Topsfield, MA.

Isbell, L. A. 2006. Snakes as agents of evolutionary change in primate brain. Journal of Human Evolution 51, 1-35.

Pickrell, J. 2017. What if the dinosaurs had survived? In Bennett, D. (ed) Dinosaurs: the Ultimate Guide to the Prehistoric Beasts. Immediate Media, Bristol, pp. 74-83.

Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs, the View From 2019 (Part 1)

Speculative Biology, Speculation Zoology and Speculative Evolution (technically speaking, they’re not all the same one thing) have been perennially popular here at TetZoo, and I think it’s fair to say that interest in these issues is currently at an all-time high. And among the various branches of the SpecVerse that enjoy the most attention and interest is that concerning Alternative Timeline Dinosaurs… and pterosaurs, and marine reptiles, and their contemporaries. These being those hypothetical animal lineages that might have evolved in a timeline where the end-Cretaceous extinction event (properly the KPg Event) didn’t occur.

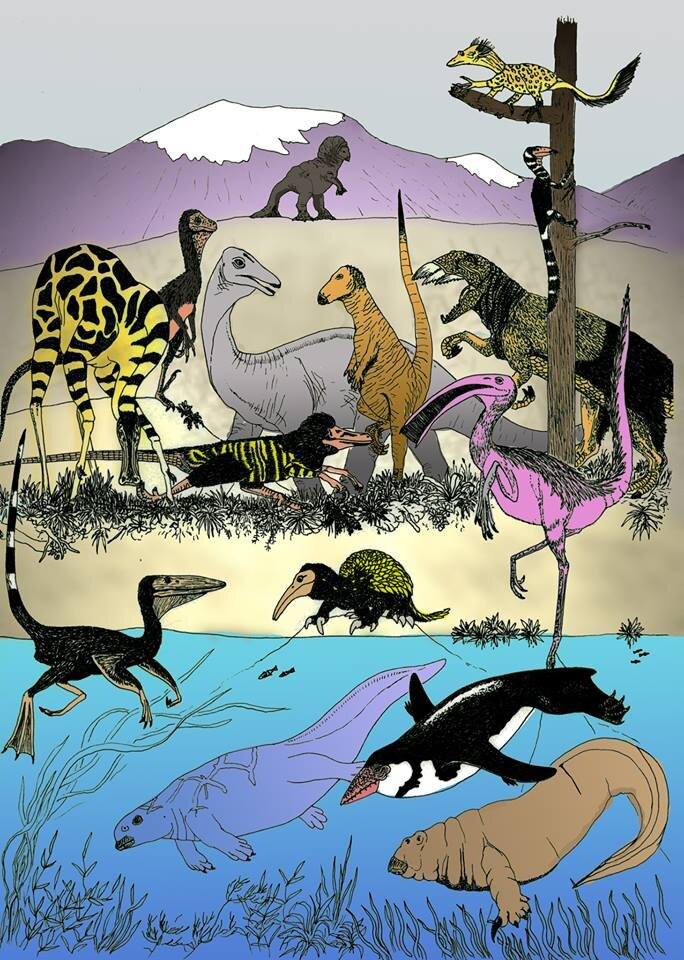

Caption: a montage of speculative dinosaurs, and one pterosaur. From left to right: McLoughlin’s Bioparaptor, Dixon’s Lank (at back), Kosemen’s Avisapiens, Dixon’s Balaclav, and a tree maniraptoran from Pickrell’s 2019 article. Some of these animals will be discussed in future TetZoo articles.

Such is the popularity of alternative timeline dinosaurs that new articles, opinions, ideas and artworks devoted to them are published on a fairly regular basis. At least some of these projects tend not – in my opinion – to give appropriate credit or mention to what’s happened before, but others certainly do. My aim in this article here (and its successors, to be published later this year) is to discuss most of the key ideas that have been covered in takes on alternative timeline dinosaurs, and to review and cite relevant literature old and new. To work.

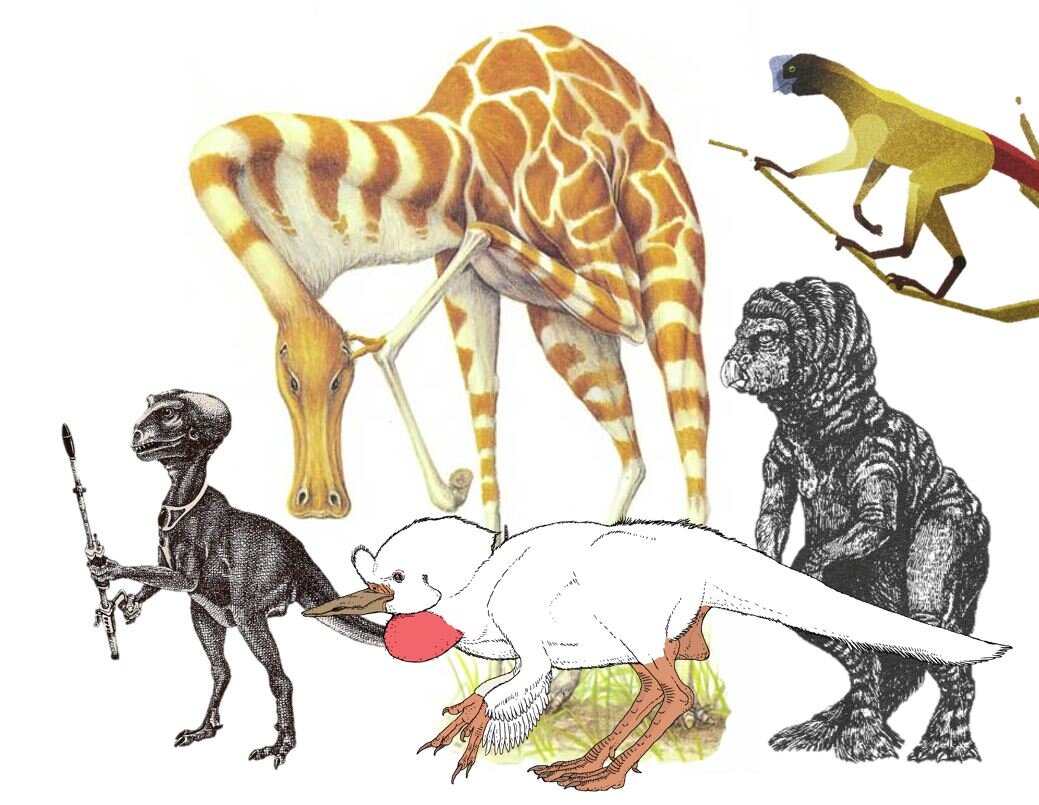

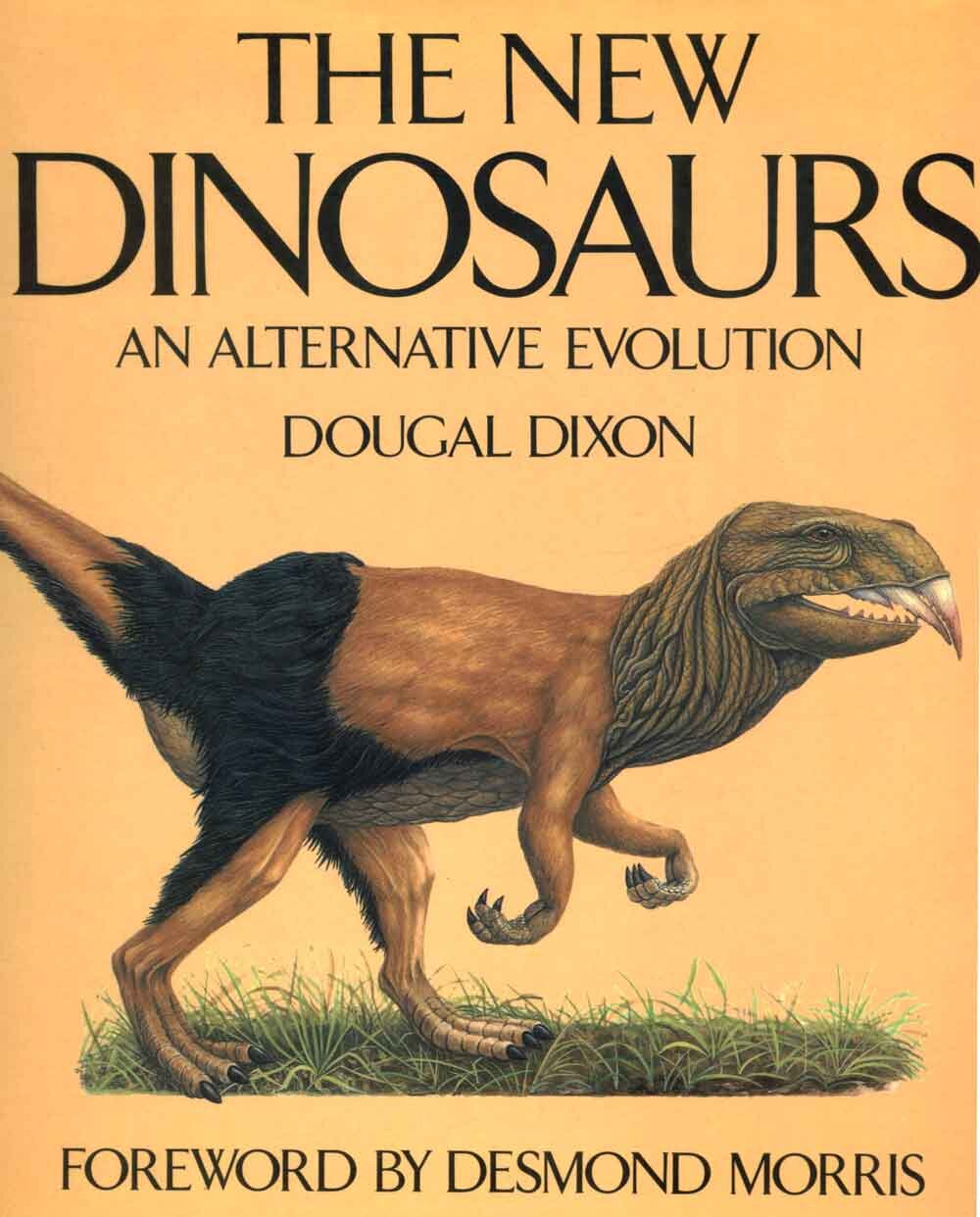

Caption: the benchmark in the world of alternative timeline dinosaurs is this book, appearing in 1988… the same year that one or two other influential books on dinosaurs appeared in print (looking at you, Predatory Dinosaurs of the World). Image: Darren Naish.

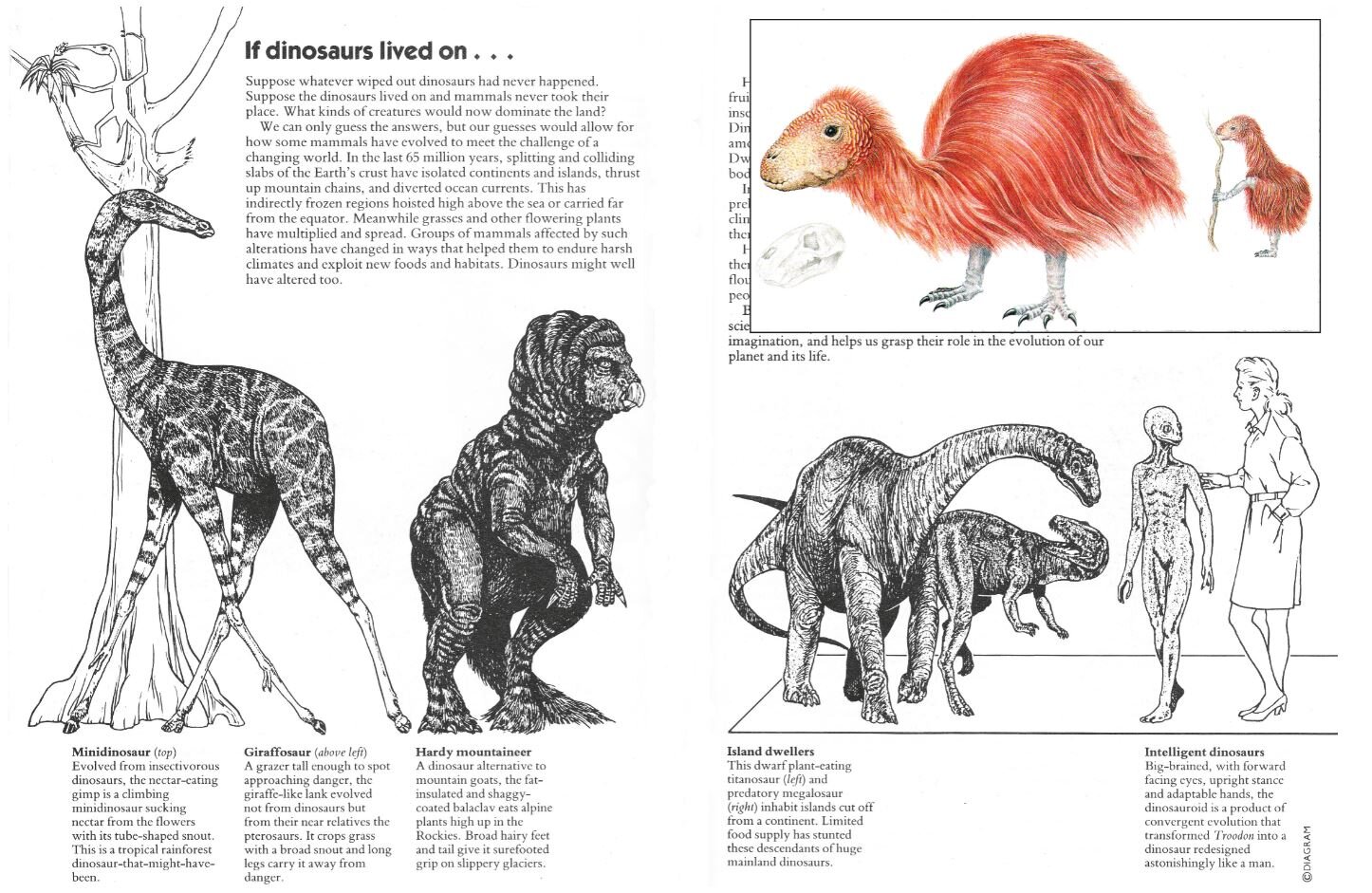

It’s fair to say that hypothetical post-Cretaceous non-bird dinosaurs have featured in fictional scenarios for almost as long as non-bird dinosaurs have been known to science, such that they star in the works of Arthur Conan Doyle, Edgar Rice Burroughs and others since well prior to the dinosaur renaissance. As significant as these works are, however, they mostly don’t get classed as SpecZoo given that they aren’t contingent on the idea that the animals have changed since Mesozoic times. With that in mind, we mostly owe the genesis of the alternative timeline dinosaur trope to two pieces of literature: Dougal Dixon’s The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution of 1988, and Dale Russell and Ron Séguin’s 1982 Syllogeus article on hypothetical big-brained theropods.

Caption: my introduction to alternative timeline speculative dinosaurs was in part thanks to David Lambert’s Dinosaur Data Book (Lambert 1990), which features this really nice montage: there are Dixonian dinosaurs from The New Dinosaurs, and Russell and Séguin’s dinosauroid at far right. The brief BBC Wildlife magazine ad on The New Dinosaurs - featuring the Kloon (top right) - also caught my imagination. For all kinds of reasons, I never saw The New Dinosaurs in bookshops. Images: Dixon 1988, Lambert 1990.

Dixon (1988) – the sequel to Dougal’s hugely successful and highly popular After Man of 1981 – portrays a modern world where dinosaurs, pterosaurs, plesiosaurs and other groups occupy the roles taken today by placental and marsupial mammals, as well as by various snakes, birds and so on. I won’t start reviewing the pantheon of creatures covered in the book here, but the illustrations below gives some idea of what we get.

Caption: a montage that depicts various of the creatures of Dougal Dixon’s TND. We see here a combination of flightless pterosaurs, climbing and terrestrial, predatory theropods, aquatic ornithischians, amphibious pterosaurs and theropods, and others. These illustrations are redrawn from those featured in Dixon (1988). Image: Darren Naish, colouring by Ethan Kocak.

I think it’s fair to say that The New Dinosaurs (TND) enjoyed a mixed response, with some reviewers hating it and others praising it (e.g., Gee 1988, Tudge 1988, Unwin 1992). The most interesting and detailed review (and, for a long time, the most difficult to obtain) is that by Greg Paul (1990). Paul was highly critical (perhaps ironically, given that his own writings and illustrations were partly inspirational) and made the interesting point that some of the most embracing of Dougal Dixon’s colleagues – Desmond Morris was one of them (he wrote the foreword) – were neither palaeontologists nor especially connected to studies of Mesozoic life. A bonus feature of Paul’s review is that it includes a novel illustration depicting his own take on alternative timeline dinosaurs, his ideas (Paul 1990) being interesting and innovative enough that they’ve inspired more recent views, on which read on.

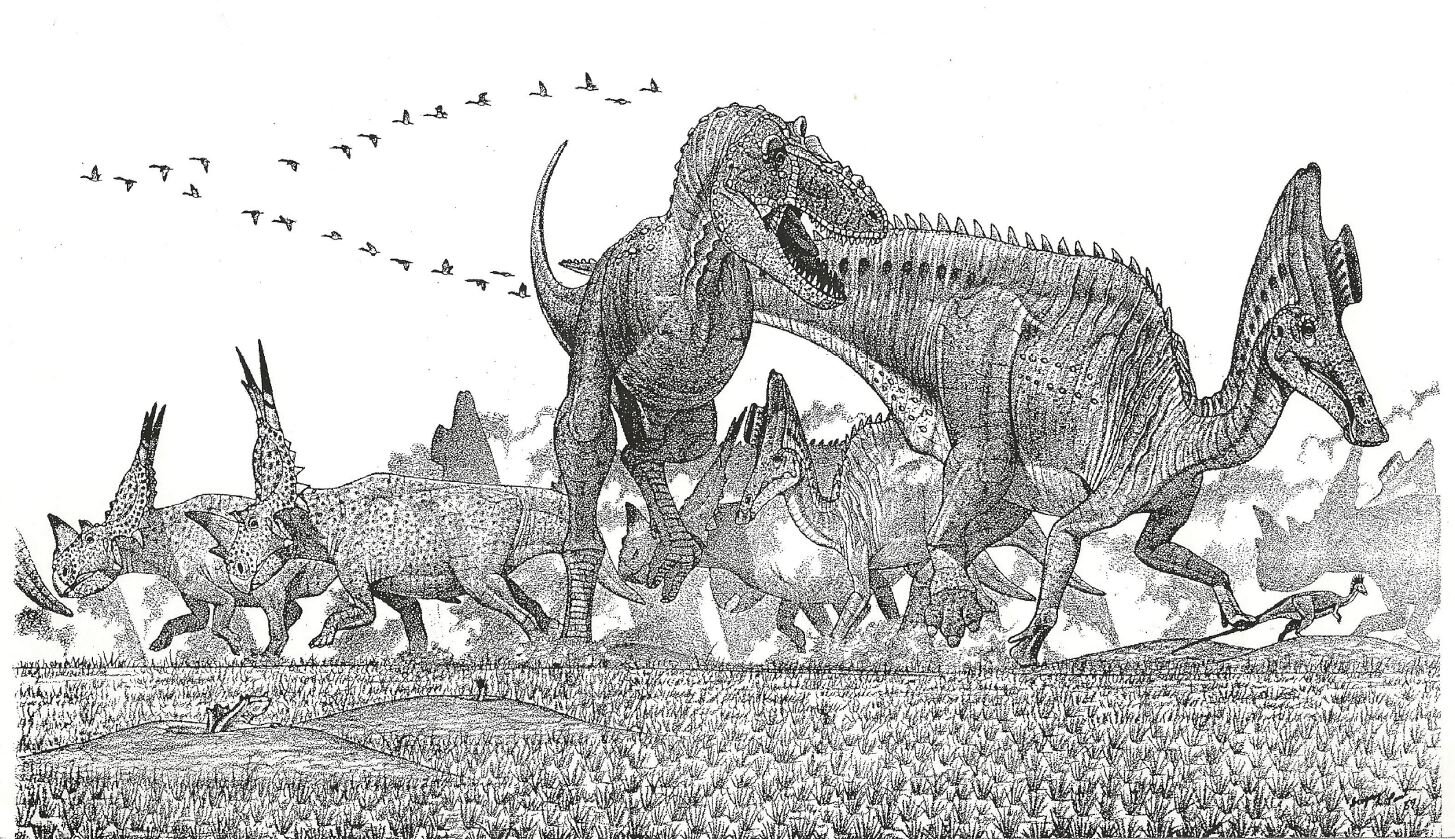

Caption: alternative timeline dinosaurs of the modern era, as imagined by Greg Paul (1990). Plains-dwelling hadrosaurs and ceratopsians are hunted by cursorial tyrannosaurs. They live alongside small, cud-chewing bipedal ornithischians, burrowing mammals and geese. Image: (c) Greg Paul.

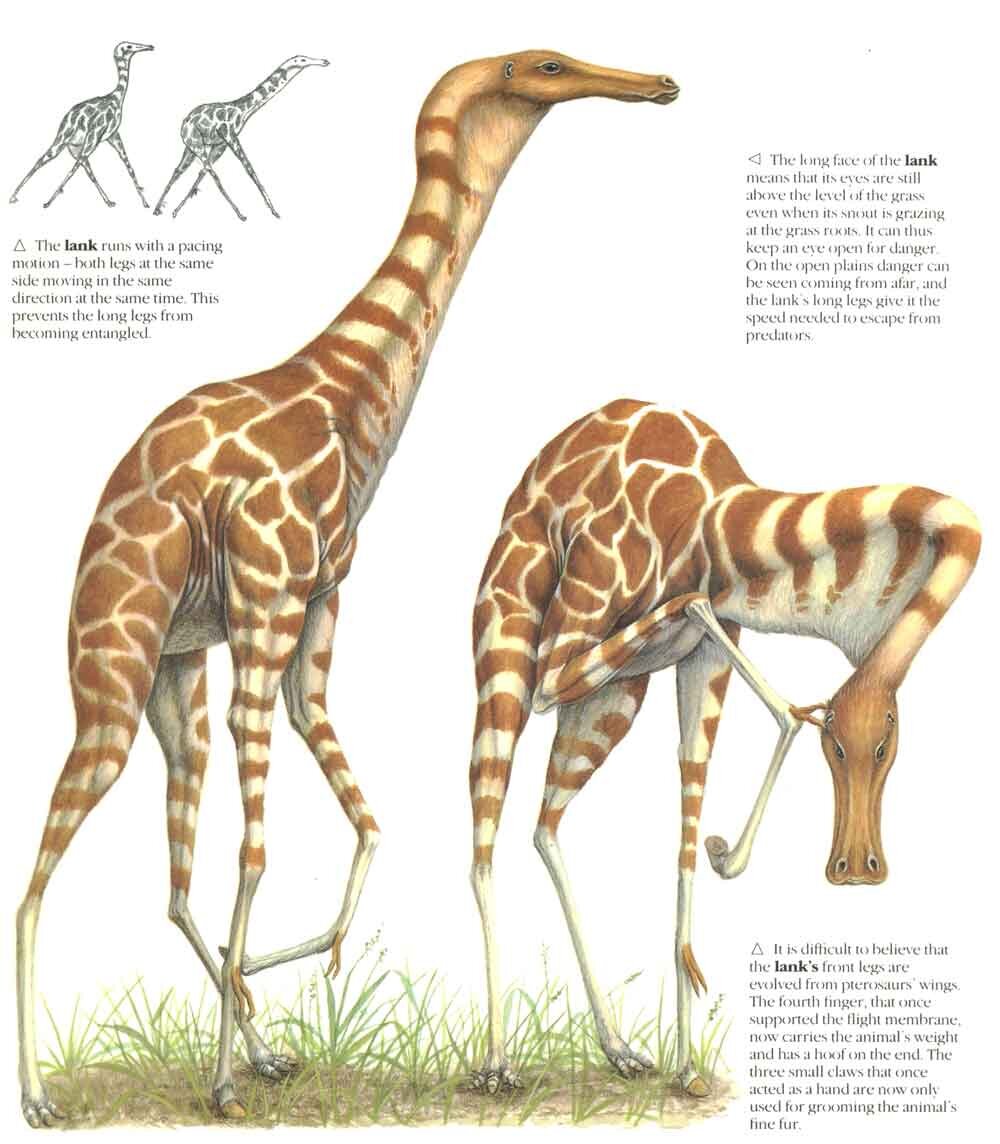

But enough on the critical reception. If anything, the pendulum has swung the other way in recent years, it being increasingly recognised that at least some of the creatures invented for TND were actually insightful and predictive. The Lank – a flightless, giraffe-like, striding pterosaur adapted to life on the grasslands – now appears oddly prescient in view of our thoughts on the ecology and lifestyle of the long-limbed, terrestrially competent azhdarchids (Witton & Naish 2008), and I wrote a 2008 article making this point. The well insulated, cool climate maniraptoran theropods and chubby, insulated ornithischians of TND also no longer look as weird as they might have in 1988 given recent fossil finds, and real-world discoveries like alvarezsaurids, scansoriopterygids, Halszkaraptor and Liaoningosaurus certainly have a Dixonian vibe to them. This was Riley Black’s point, made in this 2011 article at Laelaps.

Caption: the Lank has sometimes been criticised as one of the worst creatures of TND. But maybe this isn’t at all fair… Image: (c) Dixon 1988/Steve Holden.

Of Manga and SpecWorld. There are two other things worth saying about TND before we move on. One is that several of the species in the book appeared in a 2006 Manga volume, illustrated by Takaaki Ogawa (Dixon & Ogawa 2009). I tweeted about the book here; it’s hard to get but is a must-have if you’re a serious SpecZoo aficionado.

Caption: at left, the cover of Dixon & Ogawa (2009). At right, one of the several colour pieces included within. Images: (c) Dixon & Ogawa (2009).

The stories in the book are great fun (and you don’t need to read Japanese to follow them), but often very odd because they show the animals of the book living alongside, and interacting with, real-world animals, including crows, arapaima and Passenger pigeons Ectopistes migratorius! That’s a no-no if we’re keeping to canon, since TND actually describes a world where ‘Mesozoic’ animals have evolved to fill the niches occupied in our timeline by other animals. The second thing worth saying is that Dougal’s visions of alternative timeline dinosaurs inspired others to do the same, but in different fashion.

Caption: scenes from Dixon & Ogawa (2009), one from a Harridan-themed story (the Harridan is a raptor-like, mountain-dwelling pterosaur), and one from an Amazon-themed story involving a Pangaloon and a Watergulp. Images: (c) Dixon & Ogawa (2009).

The Speculative Dinosaur Project kicked off in 2001 and involved the invention of a substantial number of speculative animals. The website is impressive and well designed, and it’s clear that a lot of thought and discussion went into the various animals. They include long-legged, often shaggy-coated tyrannosaurs, the artiodactyl-esque ungulapedes, the sometimes gigantic cenoceratopsians (which, like Greg Paul’s alt-timeline ceratopsians, descend from non-ceratopsid ceratopsians) and many others. There’s always been talk of a Speculative Dinosaur Project book, interest in the site remains high, and there are indications right now from various minor tweaks and updates that it might be undergoing an upgrade or something sometime soon.

Caption: brilliant artwork appears throughout the Speculative Dinosaur Project. This illustration depicts a group of Eastern balundaurs, with mulongs, perfects and jaubs in attendance. Image: CC BY-SA 2.5, Speculative Dinosaur Project (original here).

A nice thing about the Speculative Dinosaur Project is that it never was devoted to non-bird dinosaurs alone, but also covered birds, crocodylomorphs, squamates and mammals in appropriate detail too. In fact, the pages on those groups were among the best parts of the site. This leads us nicely to the next area I want to discuss.

Don’t Ignore the Mammals. Of the several questions always asked in discussions about alternative timeline dinosaurs, one is ‘would humans have evolved, even in a world still dominated by non-bird dinosaurs?’. This is a good question, even if its motivation is that we might get to imagine medieval knights using dinosaurs as mounts, a line of armour-plated war ceratopsians at the Battle of Ipsus, or wonder about the role of giant dinosaurs as beasts of burden or quarry hunted by intrepid human bands equipped with specialised weapons.

The human/dinosaur coexistence thing formed the focus of a 2019 Italian magazine article by Giovanni Camardo (Camardo 2019) – titled ‘If they hadn’t died out, who would have won: us or them?’ – for which I was interviewed (the full text of my interview – in Italian – is here).

Caption: opening pages of Camardo (2019). By now, James Keuther’s CG dinosaurs might be somewhat familiar (I’ve worked with James on several projects, most notably various recent Dorling Kindersley books). UPDATE: thanks to Caleb W. (see comments), I now know that the the model was created by Raul Lunia, but then used by others. Image: (c) Focus magazine.

My suggestion – which was inspired by the Greg Paul article discussed above – is that the Cretaceous record of fossil mammals shows us both that interesting things were happening in mammal evolution late in the Mesozoic, and that at least some of the major mammal lineages were already in existence before the end of the Cretaceous. Ergo, at least some of the things that happened for real in our own timeline might still have happened in a dinosaur-dominated post-Cretaceous world. Because non-bird dinosaurs would have occupied most terrestrial niches in post-Cretaceous world, it might – I suggest, with caveats – have been difficult or impossible for mammals to get an evolutionary toehold at large body size (say, above 30-40kg or so). I’m going to call this the no megamammals rule (we’ll come back to it in the next article).

Caption: the Speculative Dinosaur Project was and is particularly good on mammals. Here are two I chose at random: the Amazonian Nekopossum (left) and the apocryphal Drop-bear, also native to South America (unlike our own timeline’s Drop-bear). Image: Speculative Dinosaur Project.

Lineages producing species below this size, however, could still have evolved pretty much as they did in our own timeline. Which means that burrowing, swimming, climbing, gliding and flying mammals – monotremes, placentals and marsupials – might still have evolved in a dinosaur-dominated world, and that a post-Cretaceous world dominated by dinosaurs might still have pangolins, shrews, moles, bats…. and primates. And if there are primates, there might still be tarsiers, lemurs, monkeys and even apes. And if there are apes, could there be the apes we call humans?

This is where we’ll pick up next. Come back soon for Part II.

For previous TetZoo articles on alternative timeline dinosaurs and related issues of SpecZoo, see…

Dinosauroids revisited, November 2006

Dinosauroid cave art discovered, March 2007

How intelligent dinosaurs conquered the world, March 2008

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

Belatedly, Nemoramjetia (= Avisapiens), November 2008

Richard Dawkins and the crappy 'humanoid dinosaurs' that just won't die, November 2009

Dinosauroids revisited, revisited, October 2012

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, June 2018

Could We Domesticate (Non-Bird) Dinosaurs?, August 2018

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018, September 2018

TetZoo Bookshelf, February 2019, Part 1, February 2019

Refs - -

Camardo, G. 2019. Se non si fossero estinti, avremmo vinto noi o loro? Focus 317, 51-55.

Dixon, D. 1988. The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution. Salem House Publishers, Topsfield, MA.

Dixon, D. & Ogawa, T. 2009. The New Dinosaurs. Futanasha, Tokyo.

Gee, H. 1988. Tales of future past. Nature 335, 505-506.

Lambert, D. 1990. Dinosaur Data Book. Facts on File, New York.

Paul, G. S. 1990. An improbable view of Tertiary dinosaurs. Evolutionary Theory 9, 309-315.

Tudge, C. 1988. End points of an alternative evolution. New Scientist 120 (1641), 65-66.

Unwin, D. M. 1992. The New Dinosaurs: An Alternative Evolution (review). Historical Biology 6, 61-71.

The Dougal Dixon After Man Event of September 2018

“Speculative biology, or speculative evolution, is a term that refers to a very hypothetical field of science that makes predictions and hypotheses on the evolution of life in a wide variety of scenarios and is also a form of fiction to an extent. It uses scientific principles and laws and applies them to a "what if" question” — the Speculative Evolution Wiki

Caption: Dixon 1981; Dixon 2018.

On September 11th 2018, I had the extraordinary privilege of appearing on stage with author, artist, editor, model-maker and visionary Dougal Dixon to discuss his famous book of 1981 After Man: A Zoology of the Future (Dixon 1981). We were joined by more than 215 interested members of the public, effectively filling the venue (Conway Hall in London).

Caption: at Conway Hall once again, such a noble venue. Image: Will Naish.

As you might have gathered if you’re a regular Tet Zoo reader, After Man has just been republished, and our on-stage event – hosted by New Lands London, and arranged by Scott Wood – also served as the launch for the new, 2018 edition (Dixon 2018). This was on sale and available for signing at the meeting.

As you can see from these photos, Dougal brought along a treasure trove of material relevant to the genesis of After Man, including his original sketches, text, draft spreads and the original page plan for the entire work. The latter consisted of large card mock-ups with small, rectangular vignettes depicting the planned look for each page. Dougal explained how he took these documents along to two – yes, just two – publishers and immediately got the green light from both. Evidently, he knew exactly what he was doing.

Caption: Dougal on stage, showing the original page plan for After Man. Small vignettes, showing the planned look of all the pages, are arranged in sequence. Image: Darren Naish.

The original sketches are excellent and a testament to Dougal’s skill and planning. The quality of these illustrations also leave you wondering why it isn’t Dougal’s art that we see in the final book, and I impressed upon him during our discussion how fantastic it would be to one day see these unpublished illustrations in another book: a ‘The Making of After Man’ or something along those lines. We’ll see.

Caption: foreign language translations of After Man, a Vortex and Raboon model, and relevant magazine issues (like the October 1981 ish of BBC Wildlife). (c) Dougal Dixon. Image: Darren Naish.

Several of the creatures pictured on the draft spreads were obvious prototypes of versions that made it into the final book but others were evidently abandoned at some point. A few of those ‘prototypes’ showed how the original animals had a different look relative to the published descendants: the bone-cracking Ghole Pallidogale nudicollum, to take one example, looked a lot more like a big mongoose in its original guise than is obvious in the book.

Caption: original text and original draft double-page spread for After Man, showing creatures inhabiting tropical grasslands. You’ll recognise some (but not all!) of the creatures as the prototypes of versions that made it to final publication. (c) Dougal Dixon. Image: Darren Naish.

Dougal also brought foreign-language editions of After Man and a few models of After Man’s creatures with him, including a resin model of the Vortex Balenornis vivipara (a reasonable number were made, but it may be that this is the only one still in existence) and a wonderfully detailed Desert leaper Aquator adepsicautus. Alas, the Night stalker Manambulus perhorridus model pictured on the dustjacket of Dixon 1981 – the model I most wanted to see – is not in Dougal’s possession so was a no-show.

Caption: Desert leaper model. For the handful of you that haven’t read After Man, the Desert leaper is a giant, desert-dwelling muroid rodent (in cases more than 3 m long) that undergoes significant fluctuation in fat deposition (and hence mass) according to season. (c) Dougal Dixon. Image: Darren Naish.

As goes our actual discussion, we covered the backstory to After Man (some of which will be familiar if you know the interview I published at ver 3 back in 2014), the response from critics and reviewers and the many overseas trips Dougal got to enjoy as a consequence of the book’s success, the substantial interest from Japanese markets and the Japanese stop-motion and animated movies (we watched a short segment from the stop-motion movie, copies of which were given away on DVD to people buying the book), the various efforts by studios in Hollywood to get an After Man movie off the ground, and the connection between After Man and Dougal’s more recent project Green World (thus far only published in Japanese).

Caption: original sketches, by Dougal, of creatures illustrated for After Man. The animals were then re-illustrated by various other artists. (c) Dougal Dixon. Image: Darren Naish.

We finished with a Q&A session and audience participation. Questions included the ‘new look’ Night stalker (yup… I shall say no more), Dougal’s thoughts on the future of humanity, how and which fossil species had influenced the creatures of After Man, and what might be different in After Man if Dougal were to write the book today.

Caption: the Vortex model that Dougal brought along. It’s about 60 cm long. (c) Dougal Dixon. Image: Darren Naish.

For a lifelong fan of After Man and Dougal’s connected writings, this event was an absolute thrill and I’m tremendously happy to have been involved. And judging by our audience’s response, it was enjoyed by everyone who attended too: thanks so much to everyone who came along and participated.

Two final things are worth saying. Firstly, I was asked innumerable times whether the event was going to be recorded. Alas, I was simply unable to organise this or even remember it given all the other stuff I had to worry about, though I think (and hope) than an audio recording exists. Secondly, this is not the only Dougal Dixon-themed event of 2018! Dougal is also on stage at this year’s TetZooCon when he will be joined by Gert van Dijk (of Furahan Biology and Allied Matters) in a discussion on speculative biology. TetZooCon happens on Oct 6th and 7th in London and tickets are still available. Dougal will also be bringing archive material to that meeting as well!

Caption: Darren Naish (l) and Dougal Dixon (r) on stage at Conway Hall, September 2018. Image: Will Naish.

My thanks to Dougal for being such a brilliant person to talk to and for all the material he brought along, to Scott and everyone else at Conway Hall and New Lands for organising things and setting it all up, to the Breakdown Press people for the book selling, and to our brilliant audience for their interest, enthusiasm and participation.

For previous articles on speculative biology, see…

Speculative Zoology: Wedel throws down the gauntlet, February 2007

Oh no, not another giant predatory flightless bat from the future, March 2007

Come back Lank, (nearly) all is forgiven, September 2008

The Tet Zoo guide to the creatures of Avatar, January 2010

The science of Godzilla, 2010, November 2010

The anatomy of Zilla, the TriStar ‘Godzilla’, November 2010

Giant flightless bats from the future, November 2010

Welcome to the Squamozoic!, April 2013

Of After Man, The New Dinosaurs and Greenworld: an interview with Dougal Dixon, April 2014

The LonCon3 Speculative Biology event, August 2014

Summer 2018 at Tet Zoo Towers, July 2018

Speculative Zoology, a Discussion, July 2018

Could We Domesticate (Non-Bird) Dinosaurs?, August 2018

Refs - -

Dixon, D. 1981. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Granada, London.

Dixon, D. 2018. After Man: A Zoology of the Future. Breakdown Press, London.