Another belated book review! Yes, let’s look at…

Five Famous Palaeolithic Rock Art Enigmas

I’m fascinated by ancient rock art and have written about it a few times here at TetZoo…

… in part because it often gives us a great deal of useful information on the life appearance of extinct Pleistocene animals. My article on the life appearance of the Woolly rhino is here, the one on Pleistocene horses is here, and the one on Megaloceros is here. As per usual, at least some of these articles have been ruined by hosting issues (if you’re patient, they’ll eventually appear in one of the Tetrapod Zoology books – which are a thing, I promise).

Today I want to talk about a few examples of Palaeolithic art that have caused controversy and uncertainty as goes what they depict. I’ve been unashamedly hokey and sensational with regard to which I’ve chosen, and have deliberately picked cases where especially odd things have been said about them, often in decidedly grey literature. This doesn’t mean that I endorse said odd things, but they’re certainly relevant and inspirational to my interests. Furthermore, they aren’t so much ‘enigmas’ as ‘ambiguous cases open to interpretation’.

I should also emphasise that I’m concentrating here on European rock art. Australian, African, Asian and North American rock art also has its fair share of intriguing images that have been the topic of contention.

Caption: the famous Lascaux ‘unicorn’ or ‘licorne’. Pretty weird that an animal with two horns ever became a ‘unicorn’, but whatevs. Credit: New Cryptozoology Tarmola Wiki (original here).

1. The Unicorn of Lascaux. Among the most famous of enigmatic rock art animal depictions is the bovid-like, horned quadruped from the ‘Hall of the Bulls’ at Lascaux, Dordogne, France, sometimes called the licorne. It’s 1.65 metres long and combines a dark, rectangular muzzle and shoulder hump with a sway back, rotund belly (leading some to suggest that it might be pregnant), short tail and dark legs. Large dark reddish blotches with pale centres cover its sides. Its most memorable feature is its two long, parallel, straight horns, which project forwards and upwards from its forehead in a manner that doesn’t really match any known animal. The fact that there are clearly two horns means that ‘unicorn’ is a total misnomer, but I guess we’re stuck with it.

Caption: the ‘unicorn’ (at far left) in the Hall of the Bulls, Lascaux Cave. Image: N. Aujoulat © MCC-CNP, from Martin-Sanchez et al. (2015).

The animal is standing at the far left of a frieze that features horses, aurochs and deer – among the best examples of their kind, in fact. The realism of the two aurochs in the same frieze is intriguing, since this somehow adds credence to the ‘unicorn’: surely it must be a realistic depiction of something real as well? Needless to say, it doesn’t match anything known to science. Is this a representation of a species otherwise unknown, it is a ‘bad’ depiction of a known species, or is it a fictional, symbolic or representational animal of some sort? Well, people have suggested a bunch of ideas.

Caption: could the ‘unicorn’ be a Chiru? I dunno, it doesn’t seem like a good match. Image: Philip Sclater, public domain (original here).

A few informal suggestions have drawn attention to the supposed cat-like form of this animal (err, not sure I see that myself… what would this mean – that it’s a bovid-mimicking horned cat? Bwahahaaaha), or the possibility that it might depict people wearing a skin as a hunting disguise (nice idea, but no way to be at all confident about it) (Eberhart 2002). The best known idea – “best known” because it was mentioned in Björn Kurtén’s Pleistocene Mammals of Europe – is probably Dorothea Bate’s that it depicts a Chiru Panthalops hodgsoni (Kurtén 1968). While there’s a really vague superficial resemblance, the spotted body and forward-canted horns of the ‘unicorn’ aren’t at all Chiru-like. The suggestion that it might be saiga is out there too, but this suffers from the same problems: the horns are the wrong shape, what’s with the spotting, and why are the key features of saiga (most notably the distinctive snout) missing?

Caption: Björn Kurtén’s Pleistocene Mammals of Europe features this composite, showing the ‘unicorn’ next to a Chiru, the idea being that they look quite similar. But I think the picture is a bit of a cheat since Chiru horns point upwards and backwards, not forwards. Image: Kurtén (1968).

2. The Sorcerer of Trois Frères. I can’t not talk about the famous ‘deer man’ of Trois Frères, Ariège, France, even though it almost certainly isn’t a depiction of a non-human (reminder: TetZoo isn’t just about non-human tetrapods). This image is 75 cm long, and is most typically imagined as an illustration (it combines both engraving and paint) of a bipedal male humanoid, standing with partly folded, short forelimbs, and with a low shoulder hump, short neck, small-eyed, bearded face, erect, deer-like ears and stout branched antlers. A curving tail and dangling male genitals are supposed to be visible as well, and prominent dark stripes run the length of the body and hindlimbs. Could this be a god-like creature believed in as a protector or object of worship? Or does it show that the artist was part of a group who believed in human-non-human transmogrification or transmutation? Is it a therianthrope (a mashup of human and non-human body parts of the sort illustrated elsewhere in the ancient world)? Or is it a semi-abstract take on a non-human bipedal creature of some sort… something unknown to science!!

Caption: a redrawing of Breuil’s interpretation of the ‘Sorcerer’, from Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams’s 1998 book The Shamans of Prehistory. As discussed in the text, this may be too generous relative to the original. Image: Clottes & Lewis-Williams (1996).

At the time of writing I’ve recently watched the 2017 movie The Ritual, and - while watching it - I couldn’t help but wonder if the creature in that movie – I’ll say no more because spoilers, but it’s called the Jōtunn – was in some way inspired by the Trois Frères sorcerer. But it wasn’t.

Caption: a scene from The Ritual, a great movie I really liked. Image: Netflix/Collider (taken from here).

Anyway, we owe this view of the figure to Abbé Henri Breuil (1877-1961), priest, archaeologist and master of French cave art. Breuil did a lot of good work and came up with many influential ideas on why, when and how cave art was produced (most famously in Breuil (1952)), but he wasn’t ashamed to speculate way beyond the confines of the data and at least some of his thoughts on the art involve a lot of interpretation that’s difficult to be at all confident about. Indeed, photos of the image show that a substantial amount of imagination is required to turn the fuzzy, partly indistinct humanoid figure visible today into the antlered novelty that Breuil depicted, and it simply isn’t possible to be confident that his take on the image is valid. Some people say that this is because photos typically don’t capture the subtleties of the images (which are often formed of cracks and lumps on the rock and hence don’t transfer well to flash photography), and others that the image may have faded or degraded since Breuil drew his take on it during the 1920s.

Caption: a post-Breuil photograph of the image. As you can see, it doesn’t definitely show the many details he thought it did. But were they present originally and later lost, or not captured in photos? Image: strangehistory.net (from here).

Whatever’s going on, there’s clearly something unusual in the original art. We’re seeing an interesting image of some kind.

3. The Lion Statuette of Isturitz. Big cats are depicted in several European caves and are most usually images of cave lions (and a whole article could be written on what that cave art tells us about life appearance and behaviour in Pleistocene European lions). A few depictions, however, show other cat species (like leopards). The Isturitz cave in Pyrénées-Atlantiques, France, yields some of Europe’s most interesting Palaeolithic art, and among this is a 16 cm long statuette of a big cat, seemingly shown with a short tail, rectangular face, prominent chin, and sparse array of spots across its upper surface. Conventionally identified as a lion, it was argued by Vratislav Mazak (1970) to instead be a depiction of the sabretooth Homotherium. This would be pretty radical for several reasons: not only would it be the only known human-made image of a sabretooth on record (though read on), it would also require that Homotherium persisted in Europe much later than anyone had previously thought (to 30,000 years ago, rather than to 300,000 years ago). The statuette is lost today (sigh), but there is at least one photo of it.

Caption: a drawing of the Isturitz statuette, borrowed from Michel Raynal’s now defunct webpage (a newer drawing of the image has since been produced by Mauricio Antón; see Antón et al. 2009). Lion or scimitar-toothed cat?

Mazak’s idea was accepted by several other authors, most notably Michel Rousseau (1971a, b), who argued that several other European Palaeolithic illustrations could depict Homotherium as well. The idea was made better known thanks to the coverage it received from Shuker (1989) and Guthrie (2005). And in 2000 it received what looked like support from the discovery of a geologically young Homotherium fossil (a lower jaw from the North Sea), dated to c 28,000 years ago (Reumer et al. 2003). So far, so good – maybe the Isturitz statuette gives us an unparalleled insight into the life appearance of an iconic sabretooth.

But… no. In a detailed re-examination of the case, Mauricio Antón and colleagues argued that it isn’t a depiction of Homotherium at all, but a Cave lion Panthera leo spelaea (Antón et al. 2009). They argued (following rigorous and detailed anatomical assessment of the life appearance of Homotherium) that the statuette lacks the longish neck, level (rather than convex) dorsal outline to the head, protruding canine tips, and sloping back that would be evident if this really was a depiction of Homotherium. I find these arguments pretty compelling and think that the statuette is a lion after all. Probably.

Caption: Antón et al. (2009) argued that Homotherium (A, B) would differ noticeably from Cave lion (C, D) in proportions. The homothere has taller shoulders, a longer neck, a flatter head, and a more sloping back than a pantherine like a lion. Image: Antón et al. 2009.

Long-time readers might recall this as something I covered way back at TetZoo ver 1. That article (with about half of all the other TetZoo ver 1 articles) is included in my 2010 book Tetrapod Zoology Book One (Naish 2010). Book Two will be published this year or in 2020, incidentally.

4. The Beast-Women of Isturitz. Isturitz is also the discovery site of an engraved piece of bone that features a bison on one side, and two humanoids on the other. The humanoids are depicted in side view, as if swimming past the viewer, and they appear to be women. But they’re very unusual women.

Caption: one of several photos showing the famous Isturitz ‘bison and two women’ engraved bone shard. This is a replica on display at Musée d'Archeologie Nationale et Domaine, St-Germain-en-Laye. Image: Don Hitchcock, from donsmaps.com.

For one thing, while they’re certainly human-like, they aren’t as human-like as regular humans. The one breast we see is shown hanging from the armpit region, rather than at the front of the chest, the profile of the face is not especially human-like and features an unusual protruding nose, and the body is unusually massive and stocky, exceeding the proportions of a human with substantial body fat. Additionally, the figures have collars or binding around their necks and wrists, and one of them has a barbed harpoon symbol on its thigh – the exact same symbol elsewhere shown on prey animals, like the bison on the other side of the engraving.

Caption: drawings of the same piece, this time showing both the bison side and the ‘two women’ side. Image: this version appeared in Heuvelmans & Porchnev, but is taken here from donsmaps.com.

The most likely explanation is that these are stylized or badly drawn figures, and that we’d be silly to over-interpret them and think that they’re meant to be anatomically accurate in all their details. Perhaps the harpoon symbols show the images represent one or more particularly unpopular members of the tribe (maybe this is even a deliberate parody or cartoon), or perhaps this is a sort of Palaeolithic ‘most wanted’ poster (Bahn & Vertut 1997) and maybe the collars and wrist bindings are just ornaments or jewellery.

I can’t resist mentioning, however, the far more out-there idea that these aren’t depictions of Homo sapiens, but of another hominin species, and one that differs from ours in being more massive, different in head and nose shape, and in being regarded by us as an enemy or prey species, or even a beast of burden. The idea has been seriously proposed in the cryptozoology literature wherein it’s argued that ancient humans knew, and sometimes depicted in art, a more bestial, snub-nosed hominin that was perhaps part of H. neanderthalensis (Loofs-Wissowa 1994, Raynal 2001, Heuvelmans 2016). Regular readers will recall me covering this very niche take on prehistoric hominins in my 2016 review of Bernard Heuvelmans’s book Neanderthal: the Strange Saga of the Minnesota Iceman. I don’t think it’s a valid take on these illustrations, but… come on, it’s such a fun idea.

Caption: Heuvelmans and a few other authors argued that Neanderthals were bestial creatures with an enlarged upturned nose. I covered this whole take on Neanderthals in my review of Heuvelmans (2016), here. Image: Heuvelmans 2016.

5. Great auk… or Long-Necked Sea Monster? Finally, birds are not especially abundant in ancient rock art, but nevertheless such species as owls, swans, geese, duck and herons were all depicted on occasion. Among the most interesting of ancient birds in rock art are those at Cosquer Cave in Marseille, France, an amazing cave – discovered in 1985 and only announced in 1991 – with a submerged undersea entrance. The birds here are big-bodied, short-legged, and with flipper-like wings and a small head, and the most popular identification is that they’re Great auk Pinguinus impennis*. That would be a big deal since it would be the first rock art of that species; it would also be consistent with fossil evidence showing that this species occurred in the Mediterranean during prehistoric times.

* An error meant that these birds were initially announced as ‘penguins’. As many as you will know, the term penguin was originally applied to the Great auk, and only later applied to the sphenisciforms of the south.

Caption: the Cosquer Cave ‘penguins’. I don’t know who to credit this image to but will add info when I get it.

However, the Cosquer Cave illustrations don’t look much like Great auks at all – this suggestion could be completely wrong, or it could be that they’re schematic or abstract depictions of this species. Indeed, some experts think that providing a specific identification like this is going too far and that it might be better to just identify them as generic seabirds (Bahn & Vertut 1997).

Caption: is the Cosquer Cave animal really a depiction of a Great auk? Hmm, maybe… but the similarity isn’t actually convincing. Images: auk by Darren Naish; Cosquer Cave animal from Mysterious Universe (here).

An even more exotic suggestion is that the massive body, stumpy tail, flippers and small head of these animals makes them look like…. the long-necked sea monster – a sort of enormous seal with a long neck and a humped back – endorsed by some cryptozoologists (most famously Bernard Heuvelmans, who proposed the name Megalotaria longicollis for this creature).

Caption: one of the most familiar depictions of Megalotaria is this painting from Janet and Colin Bord’s article on sea monsters from the partwork series The Unexplained (and latterly included in the book Creatures From Elsewhere). Not sure who the artist was. Image: (c) Orbis Publishing.

Yes, the idea that these might be depictions of a sea monster are out there in the cryptozoology literature, specifically in a 1994 article by François de Sarre*. Given that this idea requires Megalotaria to be real (something I don’t endorse, regretfully: see Woodley et al. 2008), I don’t think that this is an especially good idea, though I do agree that there’s a superficial similarity.

In the end, the idea that these images can be precisely identified to a species is probably erroneous, as it is in many similar cases. People must surely have drawn things badly, or in abstract fashion, or perhaps with only partial or second-hand knowledge of the animal concerned. And sometimes they might have made things up, or mashed things together.

* I’ve misplaced my copy of this article and can’t provide the full citation. But an online version is here, and an article inspired by de Sarre’s is here.

And that’s a good point to end on. Prehistoric rock art – produced over tens of thousands of years, by all manner of different groups of people with all kinds of influences, motivations, beliefs, experiences, artistic techniques, materials and technologies – no more performs the same function as human-made images do in the modern world. Some depictions were meant to be true to life, and to be educational, practical or naturalistic; others were abstract, symbolic, whimsical or even satirical; and surely others were practise pieces, or the work of individuals less skilled than others. We must not, I think, assume that everything can be identified to a known animal species with certainty or confidence.

For previous TetZoo articles on ancient rock art and related issues, see…

The late survival of Homotherium confirmed, and the Piltdown cats, March 2006

Tet Zoo picture of the day # 3 (Elasmotherium), May 2007

The remarkable life appearance of the Woolly rhino, November 2013

Spots, Stripes and Spreading Hooves in the Horses of the Ice Age, February 2015

The Life Appearance of the Giant Deer Megaloceros, September 2018

Refs - -

Antón, M, Salesa, M. J., Turner, A., Galobart, Á. & Pastor, J. F. 2009. Soft tissue reconstruction of Homotherium latidens (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae). Implications for the possibility of representations in Palaeolithic art. Geobios 42, 541-551.

Bahn, P. G. & Vertut, J. 1997. Journey Through the Ice Age. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

Breuil, H. 1952. Four Hundred Centuries of Cave Art. Hacker Art Books.

Kurtén, B. 1968. Pleistocene Mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London.

Loofs-Wissowa, H. 1994. The penis rectus as a marker in human palaeontology? Human Evolution 9, 343-356.

Martin-Sanchez, P. M., Miller, A. Z. & Saiz-Jimenez, C. 2015. Lascaux Cave: an example of fragile ecological balance in subterranean environments. In Engel, A. S. (ed) Microbial Life of Cave Systems, De Gruyter, pp. 279–302.

Mazak, V. 1970. On a supposed prehistoric representation of the Pleistocene scimitar cat, Homotherium Farbrini, 1890 (Mammalia; Machairodontinae). Zeitschrift fur Saugertierkunde 35, 359-362.

Naish, D. 2010. Tetrapod Zoology Book One. CFZ Press, Bideford.

Raynal, M. 2001. Jordi Magraner’s field research on the bar-manu: evidence for the authenticity of Heuvelmans’ Homo pongoides. In Heinselman, C. (ed) Hominology Special Number 1. Craig Heinselman (Francestown, New Hampshire), unpaginated.

Reumer, J. W. F., Rook, L., Van Der Borg, K., Post, K., Mol, D. & De Vos, J. 2003. Late Pleistocene survival of the saber-toothed cat Homotherium in northwestern Europe. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23, 260-262.

Rousseau, M. 1971a. Un félin à canine-poignard dans l’art paléolithique? Archéologia 40, 81-82.

Rousseau, M. 1971b. Un machairodonte dans l’art aurignacien? Mammalia 35, 648-657.

Shuker, K. P. N. 1989. Mystery Cats of the World. Robert Hale, London.

The Life Appearance of the Giant Deer Megaloceros

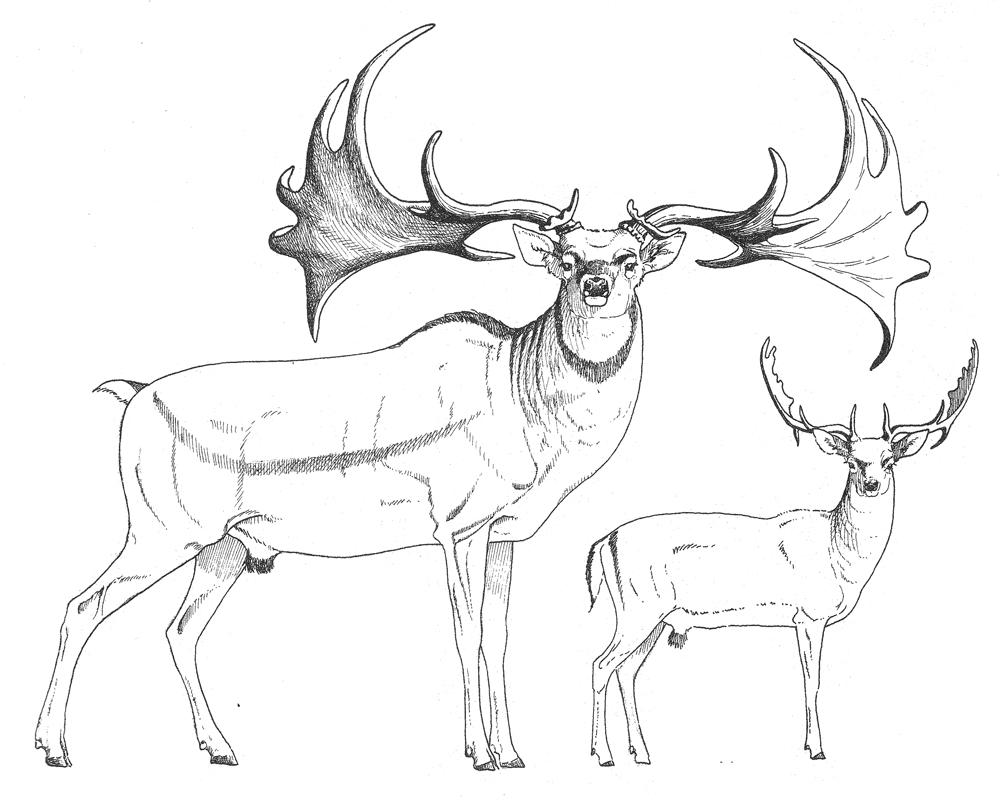

Eurasian Pleistocene megafauna are among the most familiar and oft-depicted of prehistoric animals. And among these grand, charismatic and imposing animals is the giant deer Megaloceros giganteus, an Ice Age giant that occurred from Ireland and Iberia in the west to southern Siberia in the east. It persisted beyond the end of the Pleistocene, surviving into the Early Holocene on the Isle of Man (Gonzalez et al. 2000) and western Siberia (Stuart et al. 2004)*. It is often erroneously termed the Irish elk, though it certainly wasn’t restricted to Ireland, nor should it really be termed an ‘elk’ (ugh… we’ll avoid that whole hornet’s nest for the time being). It’s been termed the Shelk by others [UPDATE: but see comments!!]. It could be 1.8 m tall at the shoulder and weigh somewhere around 600 kg, the antlers spanning 3.5 m in cases and weighing 35-45 kg (Geist 1999).

Caption: a very conventional, traditional image of Megaloceros giganteus: it's depicted looking like a giant red deer, basically. Males and females are not that different in size, but males are often shown as maned. Most interest in this deer has, of course, concerned the spectacularly antlered males. This image is from Hutchinson's Extinct Monsters (published several times over the 1890s). Image: Hutchinson (1892).

* In a previous edit of this article, I said that M. giganteus also survived into the Holocene in central Europe, as demonstrated by Immel et al. (2015). I missed the fact that this research concerns specimens dated to the Upper Pleistocene, not the Holocene. Furthermore, I’ve also been told that the Isle of Man data proved incorrectly dated. Am chasing confirmation on this.

While big, M. giganteus was not the biggest deer ever, since it seems that the extinct, moose-like Cervalces latifrons was even bigger. I promise to talk more about that species when I get round to discussing moose and kin at length. And while the antlers of M. giganteus were obviously very big, they weren’t especially big relative to its body size: proportionally, they were about similar in size to those of large Fallow deer Dama dama, and well exceeded in proportional size by the antlers of reindeer and caribou.

Caption: a fine Megaloceros skull on show at London's Grant Museum. I seem to recall hearing or reading - possibly in one of Stephen J. Gould's papers - that this is one of the largest specimens in existence. Image: Darren Naish.

I should add that M. giganteus was not the only Megaloceros species. Several others are known, differing in how palmate or slender and branching their antlers were, and not all were as large as M. giganteus (some were island-dwelling dwarves). There are other genera within this deer lineage (Megacerini) as well. Also of relevance to our discussion here is the position of these deer within the cervid family tree. Some experts have argued that megacerines are close to deer like the Red deer Cervus elaphus (Kuehn et al. 2005), while others point to genetic and morphological data indicating a close relationship with the Fallow deer Dama dama (Lister et al. 2005, Hughes et al. 2006, Immel et al. 2015, Mennecart et al. 2017). I have a definite preference for the latter idea, and right now it's a far better supported relationship than the alternative.

Caption: male M. giganteus skulls in the collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, examined in 2008. Yes, there is indeed a preponderance of males. Image: Darren Naish.

Like most European people who’ve been lucky enough to visit museums and other such institutions, I’ve seen Megaloceros specimens on a great many occasions – there are a many of them on display. I’ve also seen and handled a reasonable number of the Irish bog specimens during time spent in Dublin. There does appear to be a preponderance of big, mature males. Maybe this reflects collecting bias (in that people were more inclined to extract the skulls and skeletons of big, prominently antlered males), but it also seems to be a valid biological signal: it has been argued that the calcium-hungry males were likely attracted to calcium-rich plants like willow at the edges of lakes and ponds, and were thus more prone to drowning, miring or falling through ice in such places than females (Geist 1999). Oh, we also know that male mammals across many species are more inclined to take stupid risks, be reckless, and even display deliberate bravado more than their female counterparts.

Here we come to the main reason for this article: what, exactly, did M. giganteus look like when alive? I’ve surely mentioned this topic on several occasions over the years here; I’m pretty sure I threatened to write about it after producing similar articles on the life appearance of the Woolly rhino and Ice Age horses. M. giganteus has been illustrated a great many times in works on prehistoric life, and the vast majority of reconstructions show it a near-monotone dark brown or reddish-brown. It’s very often depicted with a shaggy neck mane. In short, it’s usually made to look like a big, shaggy Red deer, and the tradition whereby this is done – it extends back to Zdenek Burian, Charles Knight and other founding palaeoartists – seems to me to be another of those palaeoart memes I’ve written about before. I’ve taken to calling this one the ‘Monarch of the Glen’ meme (see my palaeoart meme talk here). I will add here that we're generally talking about males of the species (since people mostly want to see depictions of specimens with those awesome antlers), though virtually all that I say below applies to females too.

Alas, this view of M. giganteus is almost certainly very wrong. Why do I say this?

Caption: note the many obvious external features of this male Fallow deer: a throat bulge corresponding with the larynx - an 'Adam's apple' - is obvious, and this is a boldly marked deer overall, with prominent spots (including some that have coalesced into stripes), a white rump patch, and pale ventral regions. If megacerines are close kin of Dama deer, we might predict a similar ancestral condition for Megaloceros and its relatives. Image: Dave Hone.

Firstly, if we look at the colours and patterns present across cervine deer as a whole, we see quite a bit of variation and no strong and obvious reason why a ‘Red deer look’ should be favoured. Secondly, we have that data indicating that M. giganteus is phylogenetically closer to Dama deer than to Cervus, in which case we would predict that it descended from ancestors with prominent spotting, pale flank stripes, and dark markings on the tail, all features typical of modern Dama populations. If the ‘Dama hypothesis’ is correct, there is again no reason to favour a ‘Red deer look’ for M. giganteus. Thirdly, body size, limb proportions, antler size and habitat choice all indicate that M. giganteus was an open-country (Clutton-Brock et al. 1980), cursorial specialist, and in fact the most cursorial of all deer (Geist 1999). Cursorial, open-country artiodactyls are often pale, with large white areas across the rump, legs and belly (examples include addax, some Arctic caribou and some argali). Again, no reason here to suspect that ‘Red deer look’.

And... fourthly, we have direct eyewitness data on the life appearance of this animal. Members of our own species saw it in life and drew it, seemingly to a very high degree of accuracy. What did they show?

Caption: the famous panel at Cougnac, southwest France, showing M. giganteus males and females. This part of the cave is also interesting in depicting a short-horned bovid (at upper right) sometimes interpreted as a tahr. There are also ibex here too. I'm uncertain of the exact origin of the photo shown here: I took it from Fabio Manucci's blog Agathaumus. Numerous additional photos of the same cave can be seen at Don's Maps.

Virtually all cave art depicting M. giganteus shows a rounded, tall shoulder hump that’s sometimes shown as if it had a crest of raised hairs. Guthrie (2005) termed this a ‘hackle tuft’. There’s no obvious indication from the skeleton that a hump like this was present (indeed, fatty humps in mammals very often do not have an underlying skeletal correlate), so this is a neat thing that we wouldn’t know from skeletons alone. A protruding lump on the throat that seems to correspond to the larynx is also shown in images at Lascaux, Roucadour and elsewhere (Guthrie 2005). This feature is very reminiscent of Fallow deer.

Caption: cave art depicting M. giganteus is not all that numerous (most ancient depictions of deer are of reindeer or red deer), but what does exist shows several details worthy of note, here emphasised in illustrations produced by R. Dale Guthrie. The shoulder hump is a consistent feature. Image: Guthrie (2005).

Some of the art provides information on pigmentation. A collar-like band is depicted encircling the neck in images from Chauvet and Cougnac, the shoulder hump is shown as being dark in images from Cougnac and elsewhere (Lister 1994), and some of the Chauvet and Roucadour images show a dark diagonal line that extends across the side of the body from the shoulder to the edge of the groin, and sometimes across the leg as far as the hock (ankle). An especially detailed image at Cougnac, partially illustrated on a stalactite, shows what looks like a dark vertical stripe descending from the shoulder hump and forming a division between the deep neck and the rest of the body. The same image also shows dark near-vertical markings around what might be a pale rump patch (Guthrie 2005).

Caption: other people have taken the same evidence I've discussed here and produced very similar reconstructions. This piece - which I hadn't seen until after producing my own illustrations (on which, see below) - is by Pavel Riha. Image: Pavel Riha, CC BY-SA 3.0.

If these details have been interpreted correctly, M. giganteus was boldly marked, with obvious dark striping across its neck, shoulders and torso, and on its rump too. R. Dale Guthrie proposed that the vertical shoulder stripe formed a boundary between a near-white neck and head region and the rest of the body, with the latter being pale just posterior to the stripe but darker across the legs, rump and flank (Guthrie 2005). I’m not absolutely convinced by the evidence from cave art for a near-white neck and head or for a white rump patch but these things are consistent with what I said above about the open-country lifestyle and cursoriality of this deer. Geist (1999) was a fan of this idea, and his reconstruction of M. giganteus – shown here – is meant to show the animal as being quite pale apart from its obvious striping and other dark markings.

Caption: M. giganteus as reconstructed by Valerius Geist, and shown to scale with the extant Dama dama. Geist was (and presumably is) a strong advocate of the idea that megacerines (yes: megacerines, not 'megalocerines') are part of the same lineage as Dama. Image: Geist (1999).

Guthrie produced a very striking illustration depicting all of these details, but his drawing, as reproduced in his book (Guthrie 2005), is less than 4 cm long. Here it is (below), but note that I’ve produced a larger illustration here (scroll down) that shows the same details.

Caption: at left, the best of the M. giganteus images from Cougnac in France, as re-drawn by Guthrie (2005). At right, Guthrie's reconstruction of the animal's life appearance. Image: Guthrie (2005).

And that just about brings us to a close. Over the years, I’ve been perpetually dismayed by the fact that most people illustrating this animal aren’t aware of the information I’ve discussed here – I mean, we have direct eyewitness data that should be pretty much the first thing we take account of when reconstructing this animal. Alas, the usual problem here is that the people who provide advice on reconstructions of fossil animals to artists are virtually never that interested in or knowledgeable about the life appearance of the animals concerned (sorry, palaeontologists). That’s an unfair generalisation though, and there are of course exceptions. Indeed, I should note that accurate, informed reconstructions of M. giganteus have appeared here and there over the years: the Megaloceros depicted in the Impossible Pictures TV series Walking With Beasts, for example, includes most of the features I’ve discussed here and obviously benefitted from the input of an informed consultant.

Anyway, my hope for the article you’re reading now is that it will inspire the current generation of palaeoartists to start illustrating Megaloceros in a way that’s more in accord with the data from prehistoric art, all of which has been out there in the literature for years now (Lister 1994, Guthrie 2005).

I have further articles of this sort in mind and hope to get them published here eventually. On that note, here’s your reminder that I rely on your kind support at patreon, and that the more such support I receive, the more time and effort I can devote to Tet Zoo, and to my various book projects.

For previous Tet Zoo articles on Pleistocene megafauna, see...

Tet Zoo picture of the day # 3 (Elasmotherium), May 2007

The remarkable life appearance of the Woolly rhino, November 2013

Spots, Stripes and Spreading Hooves in the Horses of the Ice Age, February 2015

And for articles on deer, see...

Oh deer oh deer oh deer, October 2006

Deer oh deer, this joke gets worse every time I use it, November 2007

Britain: wildlife theme-park, December 2007

At the 56th SVPCA - hello Dublin! (Megaloceros), September 2008

The plasticity of deer, October 2008

Pouches, pockets and sacs in the heads, necks and chests of mammals, part IV: reindeer and a whole slew of others, October 2010

The seemingly endless weirdosity of the Milu, October 2011

South America's Many Remarkable Deer, November 2014

Confrontational behaviour and bipedality in deer, December 2014

Refs - -

Clutton-Brock, T. H., Albon, S. D. & Harvey, P. H. 1980. Antlers, body size and breeding group size in the Cervidae. Nature 285, 565-567.

Geist, V. 1999. Deer of the World. Swan Hill Press, Shrewsbury.

Gonzalez, S., Kitchener, A. C. & Lister, A. M. 2000. Survival of the Irish elk into the Holocene. Nature 405, 753-754.

Hughes, S., Hayden, Th. J., Douady, Ch. J., Tougard, Ch., Germonpré, M., Stuart, A., Lbova, L., Garden, R. F., Hänni, C. & Say, L. 2006. Molecular phylogeny of the extinct giant deer, Megaloceros giganteus. Molecular Phylogeny and Evolution 40, 285-291.

Hutchinson, H. N. 1892. Extinct Monsters, 2nd edition. London: Chapman & Hall.

Immel, A., Drucker, D. G., Bonazzi, M., Jahnke, T. K., Münzel, S. C., Schuenemann, V. J., Herbig, A., Kind, C.-J. & Krause, J. 2015. Mitochondrial genomes of giant deers suggest their late survival in Central Europe. Scientific Reports 5: 10853.

Kuehn, R., Ludt, C. J., Schroeder, W. & Rottmann, O. 2005. Molecular phylogeny of Megaloceros giganteus - the Giant deer or just a giant red deer? Zoological Science 22, 1031-1044.

Lister, A. M. 1994. The evolution of the giant deer, Megaloceros giganteus (Blumenbach). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 112, 65-100.

Lister, A. M., Edwards, C. J., Nock, D. A. W., Bunce, M., van Pijlen, I. A., Bradley, D. G., Thomas, M. G. & Barnes, I. 2005. The phylogenetic position of the ‘giant deer’ Megaloceros giganteus. Nature 438, 850-853.

Mennecart, B., deMiguel, D., Bibi, F., Rössner, G. E., Métais, G., Neenan, J. M., Wang, S., Schulz, G., Müller, B. & Costeur, L. 2017. Bony labyrinth morphology clarifies the origin and evolution of deer. Scientific Reports 7: 13176.

Stuart, A. J., Kosintsev, P. A., Higham, T. F. G. & Lister, A. M. 2004. Pleistocene to Holocene extinction dynamics in giant deer and woolly mammoth. Nature 431, 684-689.