Welcome to the second article in this short series on recently(ish) published books on the Loch Ness Monster (or LNM) (the first article is here).

Caption: the most impressive and interesting of the several Nessie paintings produced by Peter Scott - here, depicted on the back of my battered copy of the PG Tips 1987 Unexplained Mysteries of the World, written by Robert J. M. Rickard. Image: Darren Naish.

This time round, we look at the 2015 volume A Monstrous Commotion: the Mysteries of Loch Ness, a dense, thick, attractively designed volume of 365 pages that might be the only LNM-themed book that could be classed as an airport novel (Williams 2015). I confess to being unaware of Gareth Williams prior to hearing about the publication of this book. But maybe that’s understandable, since a brief biography tells us that he’s an internationally recognised expert on diabetes and obesity affiliated with the University of Bristol, has penned over 200 papers on medical topics, and has previously published books on smallpox and polio.

Caption: front cover of Williams (2015).

The volume begins with a timeline, a few pages providing potted biographies of the many human characters, a list of illustrations and some maps. The book also includes two plate sections and a smattering of black and white drawings.

The primary value of this book – its main selling point to an audience familiar with the LNM – is that it tells the backstory to the 1975 Nature paper by Sir Peter Scott and Robert Rines, a promise made in both the preface and the blurb on the back. This is the infamous paper – I’ll make the point again: published in the world’s most prestigious scientific journal – in which Scott and Rines argued not only that Nessie is real and that they had evidence proving it, but that it needed a scientific name. And thus we have Nessiteras rhombopteryx Scott and Rines, 1975 (and: no, it wasn’t a deliberately constructed anagram of ‘Monster Hoax by Sir Peter S’; to state such ignores Scott’s long-running, highly active investment and commitment to belief in the monster and his many published statements on it). The run-up to the publication of this paper, the fallout, and the alliances that were attempted, formed and broken is a fascinating story never told before in such depth, and it’s Williams’s use of Peter Scott’s correspondence that has allowed him to tell the tale. Excellent. This should be good.

Caption: Loch Ness is a beautiful and sublime place, monster or not. Image: Darren Naish.

Alas, I was immediately disappointed on finding that the book starts – as do so many books on the Loch Ness Monster – with that oh so familiar stuff about the Great Glen Fault, St Columba, kelpie legends and the stories and events of the 1930s. Clearly, we aren’t getting the Scott story alone, but the whole shebang, and while Williams writes well, I’m not sure that there’s anything in the early chapters that hasn’t been covered before.

Caption: I’ve said before that there are awful lot of books on the Loch Ness Monster… even this is far from a complete selection of what’s out there (I’m still collecting). Image: Darren Naish.

His take on Rupert Gould is admittedly interesting though. Gould – typically portrayed by authors of LNM-themed books as a bold and daring adventurer, a physical and metaphorical ex-military giant of a man who covered great distances on his motorbike and was a wise and indefatigable collector of interviews and facts, and a pioneering investigator of the unknown – is portrayed as a troubled oddball deeply affected by the frightening events of warfare. And yes, Williams does cover Gould’s eventual conclusion (about-turn, if you like) that the Spicers didn’t see a giant scientifically unrecognised (semi)aquatic vertebrate species, but “a huddle of deer crossing the road” (p. 227). Incidentally, Williams states that Gould made this private admonition in the marked proofs of his book The Loch Ness Monster and Others, but that’s not right. The annotation concerned was hand-written in a published copy and not connected at all to the manuscript during its proof stage (Binns 2017, p. 150). This is one of many minor but arguably important errors made throughout the book.

Caption: Peter Macnab’s photo of 1955. This is the version lacking the vegetation in the foreground. Regarded by some Nessie proponents as depicting two monsters swimming in close proximity, it is most likely part of a boat wake, as suggested by the lines in the water about parallel to the ‘monster(s)’. This is a scan of the original photo, provided by Dick Raynor (and available here). Image: (c) P. A. Macnab.

Post-Gould, Williams discusses Constance Whyte’s More Than a Legend and the way LNM news was received at the time before going on to discuss the pop-culture backdrop to the events of the 1960s and 70s, somehow weaving in David Attenborough and Zoo Quest for a Dragon, Jacques Cousteau and Hans Hass. After a brief skip through the adventures of Torquil MacLeod and Peter Macnab (both are among those ‘classic’ eyewitnesses who claimed, respectively, a remarkable sighting and a remarkable photo… of a boat wake), we’re introduced to one of the pivotal and most influential characters in LNMology: Tim Dinsdale, aeronautical engineer, charismatic good-guy and near-professional monster believer. Dinsdale is especially relevant to the story Williams tells because it was he – not Constance Whyte, not the preponderance of evidence, not the rash of 1930s sightings – who roped Peter Scott into the saga. I don’t want to say too much about Dinsdale here since he’ll form the focus of my third LNM-themed book review.

Caption: Torquil MacLeod’s Nessie of February 1960, observed through binoculars and estimated to be 13-15 m long, as drawn by Alan Jones for Witchell (1975). Image: Alan Jones/Witchell (1975).

What I will say for now is that Williams is by far too sympathetic to Dinsdale, failing to remark on Dinsdale’s sudden and, frankly, remarkable commitment to belief in the monster, nor is he appropriately critical of Dinsdale’s sightings or claims. Take Williams’s statement (p. 70) that Dinsdale was “catapulted into the limelight and would never escape from it”, or that “he found himself on Panorama, the BBC’s flagship news and current affairs programme” (p. 70). More accurate segments of text might read that Dinsdale “clamoured for and gained the limelight, and successfully managed to hold it upon himself for years to come”, and that “finally, he received the attention he had sought via a campaign of sending letters and telegrams, and succeeded in winning a spot on Panorama”.

Caption: Dinsdale (standing, at right) with Robert Rines (l) and Martin Klein in 1970. Image: Dinsdale (1976).

Dinsdale arrives. On reaching the part of the book that discusses Dinsdale and his Loch Ness adventures, I was finally feeling that I’d gotten through the preamble and reached the good stuff. To be clear, Williams does deliver the goods, providing a discussion and review novel enough and interesting enough to make the book a worthy addition to the LNM literature.

As noted above, it was Dinsdale who – through writing to Scott in a possibly desperate yet optimistic and bold gamble – brought Scott into the fold, his initial letter (addressed to ‘Mr Peter Scott, Naturalist, c/o BBC Television, London W1’) promising the support of a noted and reputable scientist (almost certainly Maurice Burton, then of the British Museum (Natural History)). Dinsdale’s several later letters discussed his mathematical analysis which basically consisted of calculating averages from the various eyewitness accounts that contained measurements.

Caption: Tim Dinsdale and his identikit-style view of what the Loch Ness Monster looked like. He reached this view by bundling all eyewitness accounts together and taking averages. Image: (c) Tim Dinsdale.

Why was Scott prepared to let himself be involved in the Loch Ness story? While Scott certainly stated that his belief in the monster was based on sheer preponderance of evidence (Scott 1976), Williams notes (p. xxxiii) that Scott’s interest in Nessie was quite plausibly motivated by his feeling that it could serve as a flagship species, in the same ballpark as the tiger and giant panda, for the fledgling World Willdlife Fund. Scott’s own drawings support this idea.

Caption: here’s another of the big, spectacular, Nessie-themed works of art produced by Peter Scott (this is only a section of the whole thing). Image: (c) Peter Scott.

Scott and Dinsdale met in person in 1960, but not before Dinsdale explained his plan. He would need Scott as an ally in convincing her majesty Queen Elizabeth II that Nessie was real and in need of protection. Scott knew the Royal Family, moved in the right circles, and was sufficiently impressed by Dinsdale’s argumentation to consider this an appropriate course of action, even making the suggestion that Nessie might be given the scientific name Elizabethia nessiae* (Williams 2015). Alas, Dinsdale had already written to the Royal Family by this time and his impetuousness on this front – he was to write to them several more times – partly derailed efforts to carefully, thoughtfully build a case for the monster’s existence, one that might be sufficiently interesting and carefully stated to keep sceptics, the scientific community, the media and people like the Royal Family on board.

* Incidentally, another proposed binomial – Nessiesaurus o’connori (sic: the specific name should have been written ‘oconnori’) – is also outed in this book. It was proposed by Peter O’Connor, author of the almost certainly hoaxed ‘inverted kayak’ photo of 1960, in his correspondence to Scott (Williams 2015).

Caption: by the mid 1970s, Peter Scott was happy to publicly state a belief in the Loch Ness Monster, and there are even photographs of him wearing an ‘I Believe in Nessie’ t-shirt. Here’s the cover of a magazine issue that features a key Scott article on the subject. Image: Darren Naish.

Over the months and years that followed, Scott worked to build a case, Tim Dinsdale’s film of 1960 being one of several pieces of evidence deemed crucial. The many ups and downs, false-starts, setbacks, and input and involvement of others make for a complex story that I’m not about to summarise. The eventual outcome, which had emerged by 1970, was the involvement of Americans including Chicago’s Roy Mackal and patent lawyer Robert H. Rines, the rise and fall of the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau, and a gradual parting of the ways between Scott and Dinsdale.

There’s a definite undercurrent in the book of Scott and Dinsdale working to somewhat different ends. The Dinsdale plan was to announce and promote the monster’s existence and reality as loudly and frequently as possible. The Scott plan was to form a solid portfolio of good evidence, hold formal meetings where this evidence could be presented to and digested by the right parties, and to ultimately gain legal protection for a neglected and remarkable new species honestly thought by Scott to be, most probably, a living plesiosaur (Scott 1976).

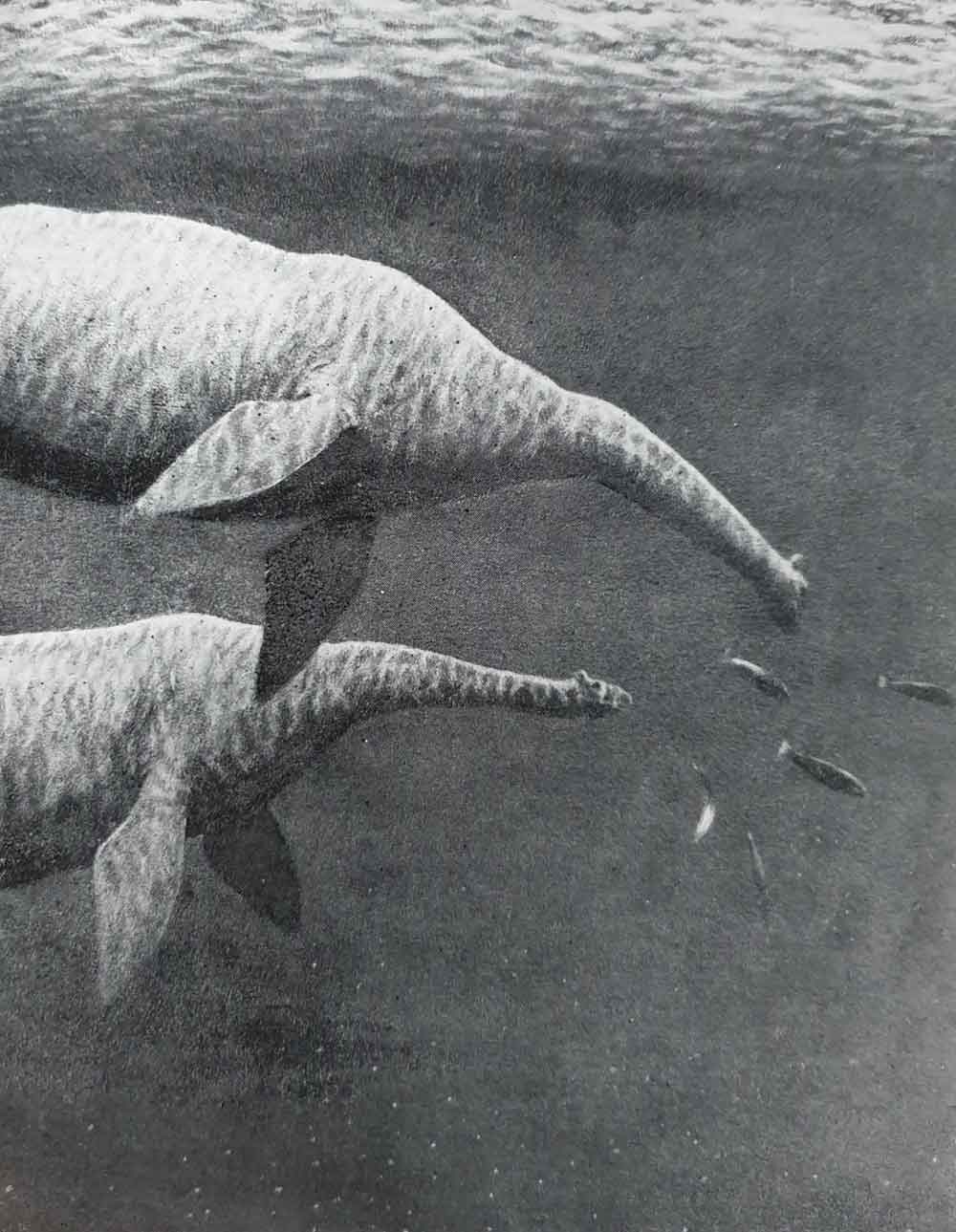

Caption: palaeontologists specialising on plesiosaurs have near universally been very hostile to the idea that the Loch Ness Monster might be a living plesiosaur. But it’s also a very familiar idea that plesiosaur experts have sometimes toyed with. This diagram is from Big Mouths and Long Necks, a short book devoted to plesiosaurs. Image: Taylor & Martin (1990).

Scott and Rines 1975, and the ‘flipper’ photos. As anyone familiar with the Loch Ness story knows, the turning point was the use of sonar detection and strobe photography in the loch, the eventual result being the presentation of photos said by Rines and his colleagues to be proof of the monster’s existence and to give insight on its form (Scott & Rines 1975, Rines et al. 1976, Scott 1976, Sitwell 1976, Rines 1982).

Caption: my own take on one of the Rines/Egerton ‘flipper photos’, drawn when I was about 14. Like many people in those years (this would’ve been drawn in the late 1980s), I had been led to believe that the photos really show the giant, diamond-shaped flippers of a very big animal. They don’t. Image: Darren Naish.

Initial claims that the flipper photos showed a pentadactyl anatomy (thereby confirming a tetrapod identity for the creature), that two diving animals, moving synchronously and close together, had been captured in a single frame and that a close-up view of the animal’s external surface revealed details of skin texture and even its parasites (Witchell 1975, p. 150), all proved embellished or inaccurate, to use the kindest words possible. We think today that the flipper photos were physically modified, that the ‘gargoyle head’ photo (which had been rotated by 90° relative to its original orientation) doesn’t depict an animal’s head but a tree stump on the floor of the loch, and that an alleged shot of the body and neck cannot be of a large animal but a small object close to the camera, most likely a submerged branch (Naish 2017).

Caption: the weird and ugly ‘gargoyle head’, interpreted as the snorkelled, horned, short-faced creature depicted at right in this painting by Peter Scott. Read on for another version of that Scott painting. Images: Rines et al. (1976), Peter Scott.

Nevertheless, it’s obvious from some of the things written at the time that these developments must have been extraordinarily exciting. I’m always struck by the following breathless words from Nicholas Witchell…

“This paper edition of The Loch Ness Story is being rushed out in the autumn of 1975 at a time when the world is about to witness one of the greatest and most dramatic discoveries of the twentieth century: the discovery and probable identification of a semi-mythical creature known throughout the world as the ‘Monster’ of Scotland’s Loch Ness.

“As the final chapter describes, a set of detailed colour photographs of the head and body of the ‘Monster’ have been taken by a highly respected American scientific team. They have set the zoological world, and will very shortly set the whole scientific and lay world, ablaze with excitement. After nearly fifty years of legend and mystery, the saga of the Loch Ness ‘Monster’ is about to end with the addition of a remarkable new (or possibly very ancient) species to the world’s animal kingdom” (Witchell 1975, unpaginated author’s preface).

Dinsdale, despite the rift that would then have existed between himself and Scott, announced his great confidence in the photos (Dinsdale 1973), and such was their apparent significance that they were reported not just in the Nature paper, but on the journal’s cover too. Here is another of Williams’s gaffs, since he describes the paper as an “anonymous item” (p. 175). In fact, Scott and Rines are clearly noted as authors in the article’s abstract (Scott & Rines 1975).

Caption: the first part of the Scott & Rines (1975) article. Image: Nature Publishing Group.

The publication of this paper is definitely one of the weirder decisions ever made by Nature and one that attracted immediate and strong criticism. Importantly, it makes a mockery of the notion, beloved of cryptozoologists, that ‘the establishment’ has forever shunned or deliberately ignored such things as Nessie. Bullshit, dudes; you had a freakin’ paper in Nature.

Caption: the Peter Scott books I own. Image: Darren Naish.

On that note, one thing that should strike you while reading this book is the extremely high number of working scientists, academic institutions and official societies that, at some time or another since the 1930s, were embroiled in the Loch Ness saga. In, again, massive and hilarious contrast to the idea that academics shun or ignore cryptozoological subjects like the Loch Ness Monster, such qualified workers as Richard Harrison and Leo Harrison Matthews (both well known for their work on marine mammals), marine biologist Sir Alister Hardy, primatologist Sir Solly Zuckerman, palaeontologist Alan Charig*, ethologist, artist, author and TV personality Desmond Morris and many others were all involved or solicited opinion at some point. Hardy, incidentally, stated his belief in the monster (Wiliams 2015, p. 94).

* I wish I’d known this when writing a biography on Charig (Moody & Naish 2010).

Caption: Robert Rines has been a mildly controversial figure, and there have been occasions in which his credentials and qualifications were called into question. Here are two letters from the pages of New Scientist, both from 1982 (vol 95, issues 1315 and 1320, respectively). Image: New Scientist.

On science and scientists, and anti-scientific statements. All in all, A Monstrous Commotion is useful in providing a great deal of novel discussion pertaining to the Scott correspondence, so far so good. But the book is somewhat ruined by a soft pro-Nessie stance that shines through in some places, the author’s insinuation being that Nessie is real and deserving of study and that those scientists and commentators who have rejected its existence and failed to take it seriously are the ones in error.

In places, he appears to unquestionably accept a few notions that, while beloved of Nessie supporters, have been so effectively countered that they shouldn’t ever be used as ‘supporting’ arguments ever again. Examples? That “the Monster [has] a pedigree that [goes] back … over 1,300 years” (p. 9) (see Magin 2001), or that coelacanths can be used to support the idea that the fossil record may as well be disregarded (p. 61).

Caption: the idea that Latimeria, the extant coelacanth, provides support for the view that Mesozoic-grade vertebrate taxa might persist to the present without leaving a fossil record is very naive. In case you hadn’t noticed, we’ve now known of Holocene coelacanths for more than 80 years. This model was on display at the Natural History Museum (London, UK) in 2013. Image: Darren Naish.

Williams notes the sometimes irksome statements made by Nessie supporters about scientists and the scientific process. Constance Whyte, describes Williams, might have seen the scientists of the day as “[a]rrogant and tunnel-visioned”, and that “they could not even be bothered to get out of their armchairs and visit Loch Ness to review the evidence for themselves. Of course, the Monster appeared to flout some basic rules of zoology, and pursuing it could be a waste of time. However, rules were made to be broken, and open-mindedness was supposed to be the hallmark of a good scientist” (p. 63). Williams continues: “All the prejudices and inflexibility of the scientific establishment had been neatly summed up by one of the leading biologists of the 1930s, Sir Arthur Keith FRS” who, Williams tells us, spoke “from the ivory tower of the Royal College of Surgeons” and went on to dismiss the beast “as a problem for psychologists, not zoologists” (p. 63). There are, of course, good reasons for thinking that Keith’s idea of a psychological explanation for monsters is a good one, not the opposite. William’s goes on to refer to the “scientific mafia” when describing the scientific response to Whyte’s 1957 book (p. 63).

Caption: The Cryptozoologicon Volume I sometimes mocks the aggressive tone used by some cryptozoologists. At right, part of John Conway’s scene of a Himalayan yeti group. Image: John Conway/Conway et al. (2013).

This sort of wording will be familiar if you’ve read my 2013 book (co-authored with John Conway and C. M. Kosemen) The Cryptozoologicon. Therein we deliberately mocked the vitriolic, vituperative, frothing-at-the-mouth-with-anger tone aimed at sceptics and working scientists by a certain cadre of cryptozoological believers (Conway et al. 2013). Fact is, the history of research on all the subjects beloved of cryptozoologists – Nessie, bigfoot, the yeti – shows that working scientists never shunned, ignored, dismissed or rejected these things but, on the contrary, spent time considering them, writing about them and even investigating them, only to get their fingers burnt when the subjects proved to mostly be a waste of time (cf Regal 2011). Look again at the list of scientists mentioned above: it’s absolutely farcical to state that scientists haven’t been interested, or haven’t bothered to investigate this stuff. To be clear: Williams isn’t guilty of painting science and scientists in this way, but he’s saying that Whyte was.

Caption: your author (on the right) with Nessie. Image: Darren Naish.

Indeed, this sort of thing – championed and given the thumbs up by at least some cryptozoologists (and their allies, the paranormalists) – only makes its proponents look naïve and clueless. Caricaturing scientists critical of the Loch Ness Monster as a ‘mafia’ implies that they work together as a band when confronted with a problem. The inner workings and politics of science involve very much the opposite, a fact often destructive and detrimental to those involved. Dear cryptozoologists critical of ‘the scientific establishment’ or of scientific sceptics in general: why do you insist on remaining so clueless with respect to what science is and how it works? There isn’t a gang or club of conspiring scientists who elect to take a given stance on a topic, but a community of competing individuals, all of whom are complex human beings.

Caption: the idea that Nessie might have retractable snorkels on its head - an odd idea, to be sure - has long been fairly popular in the LNM literature. The ‘gargoyle head’ photo has to be interpreted within this context. Image: Randall & Keane (1978).

Finally, a complaint I wish to make about A Monstrous Commotion is that it is, in places, oddly deficient in giving credit. I suppose I shouldn’t expect my own critical comments on various of the LNM photos to warrant mention since (outside of 2016/2017’s Hunting Monsters) they were only ever published here at TetZoo, not in print, but the complete and total absence of Ronald Binns – he isn’t mentioned or even cited once – is odd. Suspiciously so, given that a few sections of the book read much as if they took data or conclusions from Binns (1983). The lack of reference to the many discussions which have occurred within the various ‘parish magazines’ of cryptozoology – Fortean Times, Animals & Men, The Cryptozoology Review, Strange Magazine, Fortean Studies and so on – is also a bit odd.

Caption: more evidence for the snorkel-headed Nessie meme: this is the brilliant Kaiyodo toy. Mine was specially shipped from Japan, and oh do I love it. Image: Darren Naish.

A Monstrous Commotion is an entertaining book that I much enjoyed reading. After a slow start that I would have been happy to go without, it tells a fascinating story and does it well. Those seriously interested in the history of research and ideas on lake monsters should definitely read it, and it might even be said to be one of the best and most professional of books on the Loch Ness Monster yet published. However, it sometimes appears too sympathetic to those who supported the existence of the Loch Ness Monster, doesn’t appropriately cite all relevant sources, and has enough small, technical errors that it shouldn’t be relied on for factual accuracy.

Caption: the only versions of Peter Scott’s renditions of the ‘gargoyle head’ illustration I’ve seen online have been tiny and very low-res, so here’s my best effort at reproducing the best version I have to hand (it’s from the 1981 Reader’s Digest book Into the Unknown). Image: Peter Scott/Bradbury (1981).

Williams, G. 2015. A Monstrous Commotion: the Mysteries of Loch Ness. Orion Books, London. pp. 365. ISBN 978-1-4091-5874-5. Softback, refs. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

Nessie and related issues have been covered on TetZoo a fair bit before, though many of the older images now lack ALL of the many images they originally included…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013 (now stripped of all images, so completely useless)

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014 (now stripped of all images)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Refs - -

Bradbury, W. 1981. Into the Unknown. Reader’s Digest Association, Pleasantville, New York/Montreal.

Binns, R. 1983. The Loch Ness Mystery Solved. Open Books, London.

Binns, R. 2017. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. Zoilus Press.

Conway, J., Kosemen, C. M. & Naish, D. 2013. Cryptozoologicon Volume I. Irregular Books.

Dinsdale, T. 1973. The Rines/Egerton picture. The Photographic Journal April 1973, 162-165.

Dinsdale, T. 1976. Loch Ness Monster, Revised Edition. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London.

Magin, U. 2001. Waves without wind and a floating island – historical accounts of the Loch Ness monster. In Simmons, I. & Quin, M. (eds) Fortean Studies Volume 7. John Brown Publishing (London), pp. 95-115.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Randall, N. & Keane, G. 1978. Focus on Fact. No. 5 Unsolved Mysteries. W. H. Allen & Co, London.

Rines, R. H. 1982. Summarizing a decade of underwater studies at Loch Ness. Cryptozoology 1, 24-32.

Rines, R. H., Edgerton, H. E., Wyckoff, C. W. & Klein, M. 1976. Search for the Loch Ness Monster. Technology Review March/April 1976, 25-40.

Scott, P. 1976. Why I believe in the Loch Ness Monster. Wildlife 18, 110-111.

Scott, P. & Rines, R. 1975. Naming the Loch Ness monster. Nature 258, 466-468.

Sitwell, N. 1976. The Loch Ness Monster evidence. Wildlife 18, 102-109.

Taylor, M. A. & Martin, J. G. 1990. Big Mouths and Long Necks. Leicestershire Museums, Arts and Records Service, Leicester.

Williams, G. 2015. A Monstrous Commotion: the Mysteries of Loch Ness. Orion Books, London.

Witchell, N. 1975. The Loch Ness Story. Penguins Books, Harmondsworth, Middlesex.

![I've only had one up-close encounter with a Bigfoot myself (it happened in California); I didn't have opportunity at the time to do any checking as goes any details of anatomy, but here's the proof. Image: [safely anonymous source]/Darren Naish.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/510be2c1e4b0b9ef3923f158/1533161346909-MMK41T4JOD99AEY17TJ4/Bigfoot-in-LA-572-px-tiny-Aug-2018-Darren-Naish-Tetrapod-Zoology.jpg)