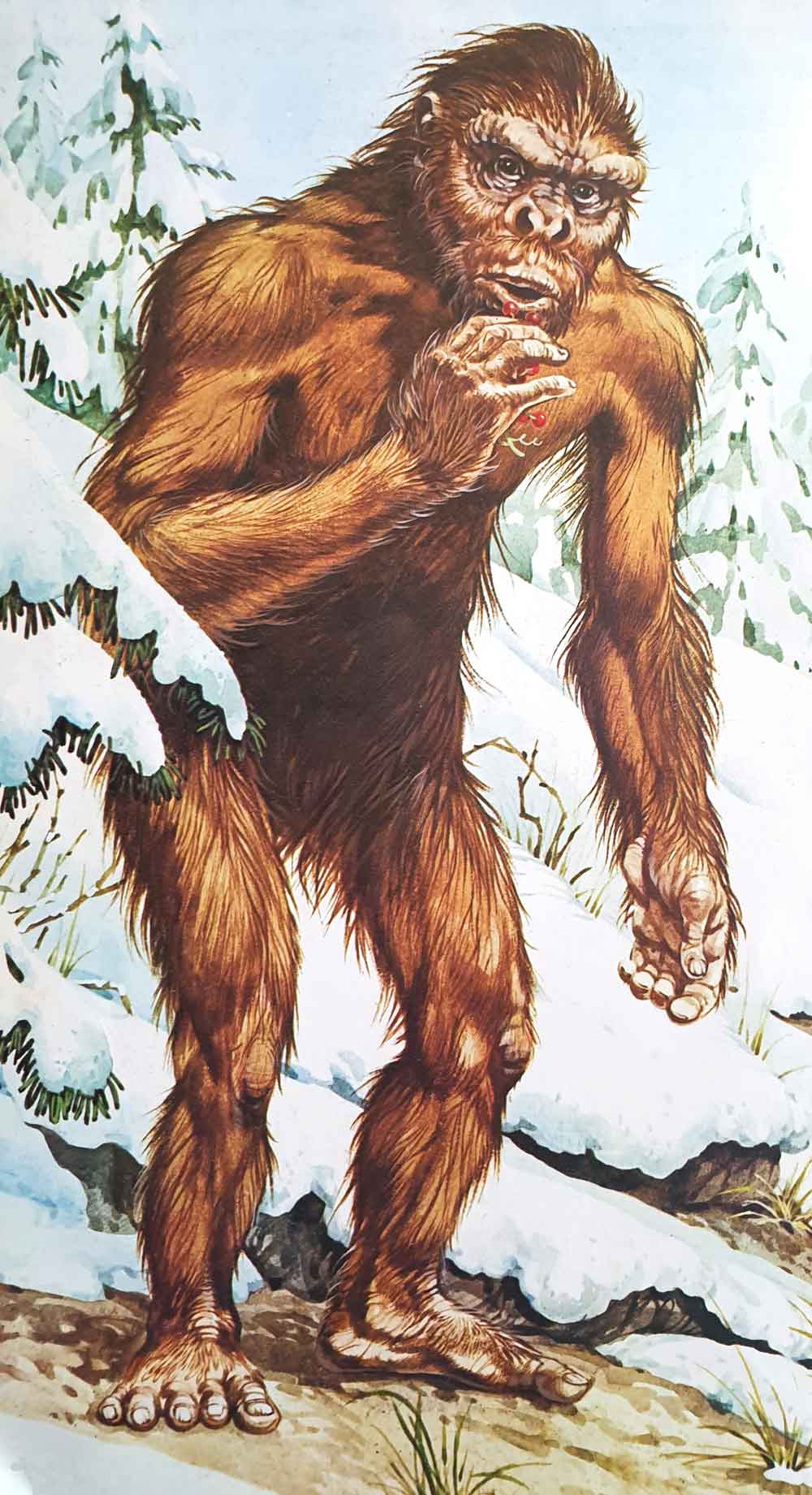

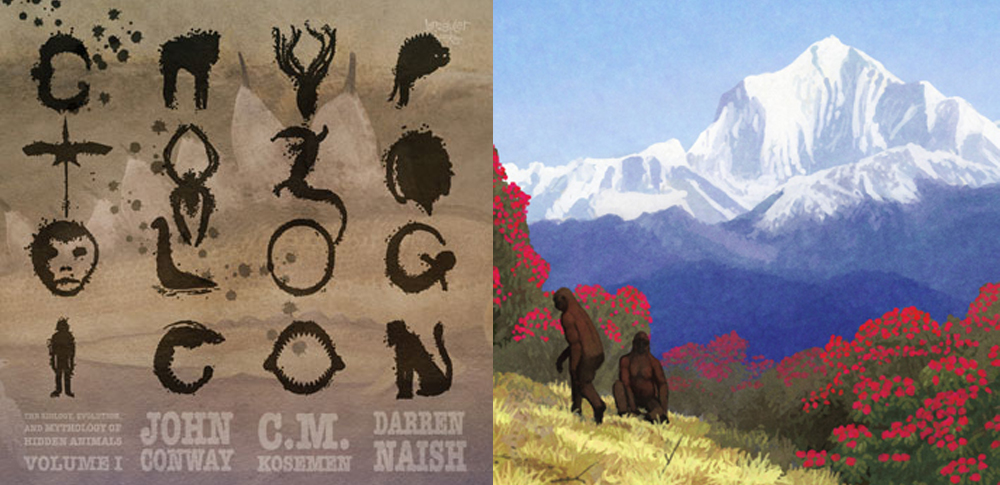

It’s been said that the present is a Golden Age for cryptozoology books, cryptozoology being the ostensible study of creatures known from legend, account or anecdote but not accepted as valid by science...

The Third Edition of Naish and Barrett's Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved

Among the proudest of my achievements is the publication of Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, DHTLE for short, co-authored with Professor Paul Barrett and published by the Natural History Museum, London. I think it’s fair to say that it’s the flagship ‘dinosaur book’ of the museum. It’s also one of only a handful of dinosaur-themed books written at ‘adult level’. “Finally, a modern, intelligent, trade book on dinosaurs for thoughtful readers”, to quote a reviewer at Quarterly Journal of Biology.

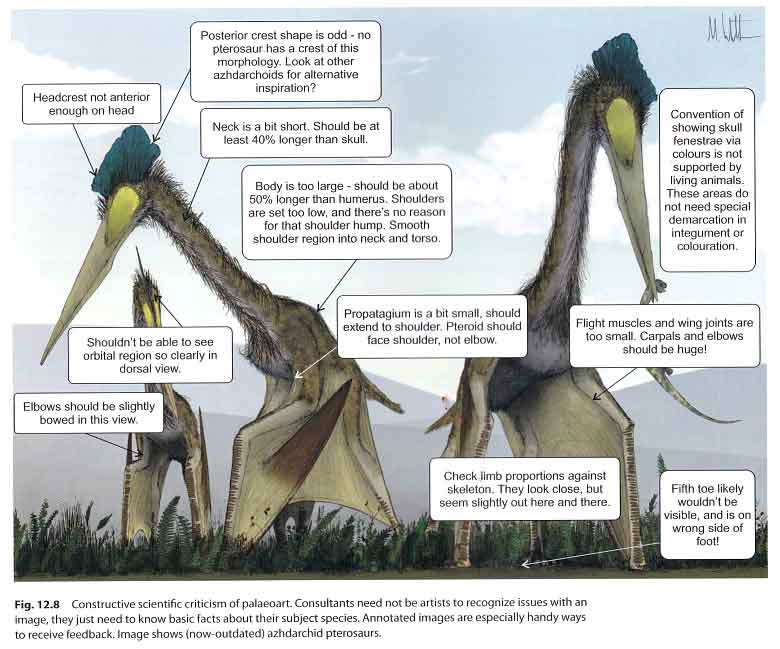

Announcing Mesozoic Art, a Lavish New Volume on Modern Palaeoart

The giant, fantastically illustrated new volume Mesozoic Art: Dinosaurs and Other Ancient Animals in Art, edited and written by Steve White and myself and published by Bloomsbury Wildlife, is now on sale…

A Look Back at Dorling Kindersley’s 2001 Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs & Prehistoric Life

My New Book: Dinopedia from Princeton University Press

Pete Dunne and Kevin T. Karlson’s Gulls Simplified: A Comparative Approach to Identification

Announcing Dinopedia, Out September 2021

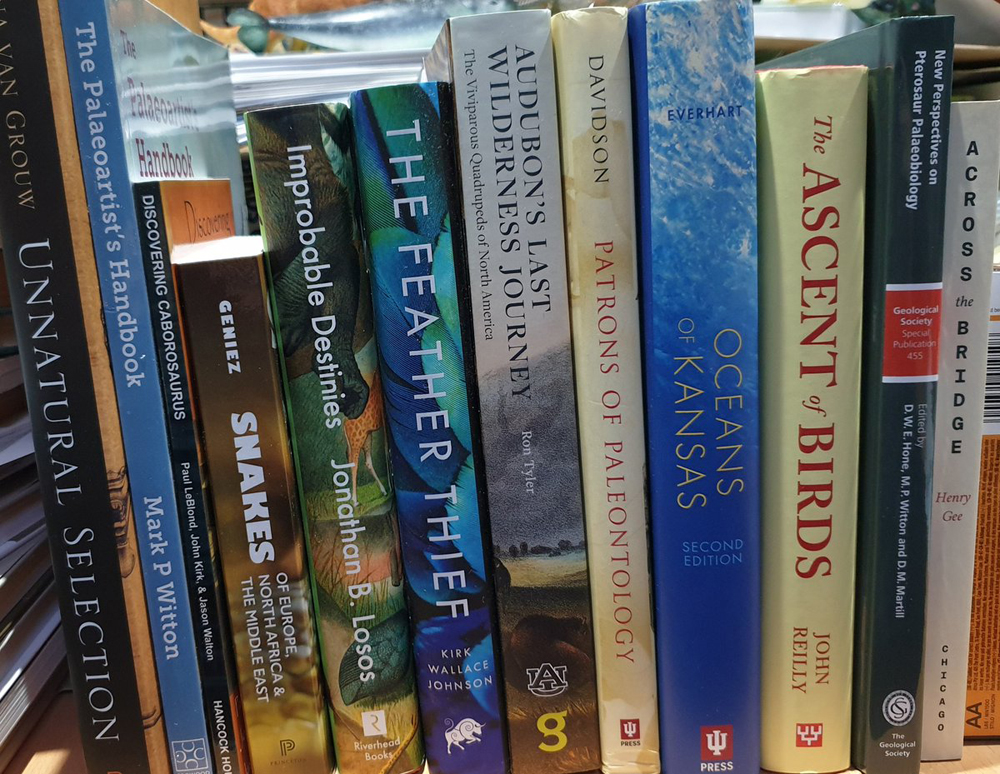

Kirk W. Johnson’s 2018 The Feather Thief, a Review

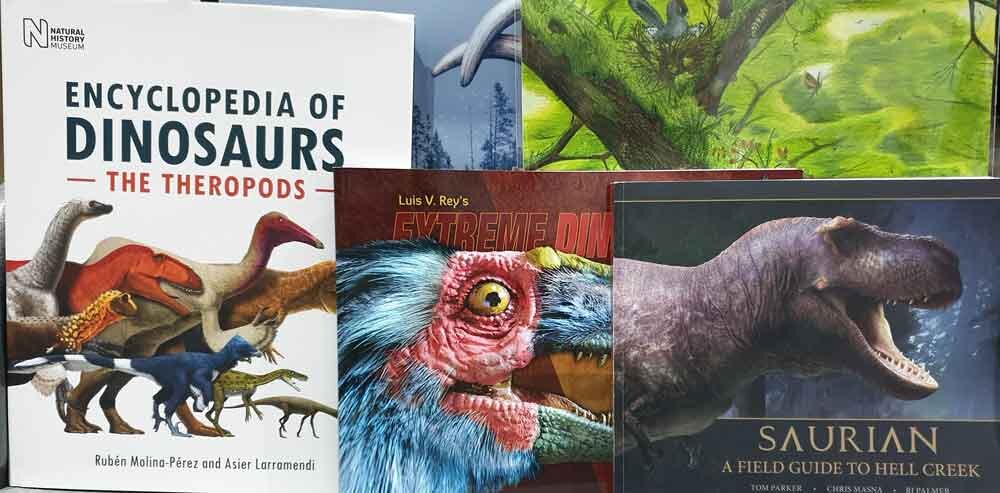

Beautiful, Big, Bold Dinosaur Books: of Molina-Pérez and Larramendi’s Theropods, Rey’s Extreme Dinosaurs 2, and Parker et al.’s Saurian

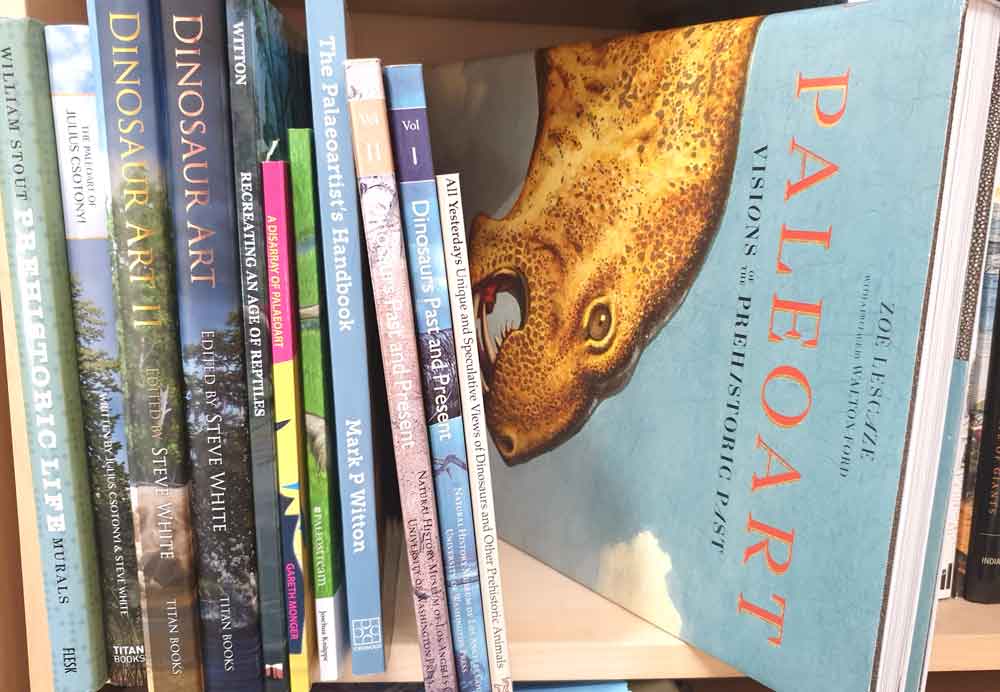

One of the reasons you read TetZoo is because of the dinosaurs, and among the dinosaur-themed things I write about on fairly regular basis are new(ish) dinosaur-themed books.

Partly because I’m way overdue on the book reviews I planned to write during 2019, I’m here going to talk about some recently-ish published dinosaur-themed books that you’d do well to buy and read, if you wish, or can. I’ve written about recently-ish published dinosaur-themed books on quite a few recent occasions; see the links below for more. Let’s get to it.

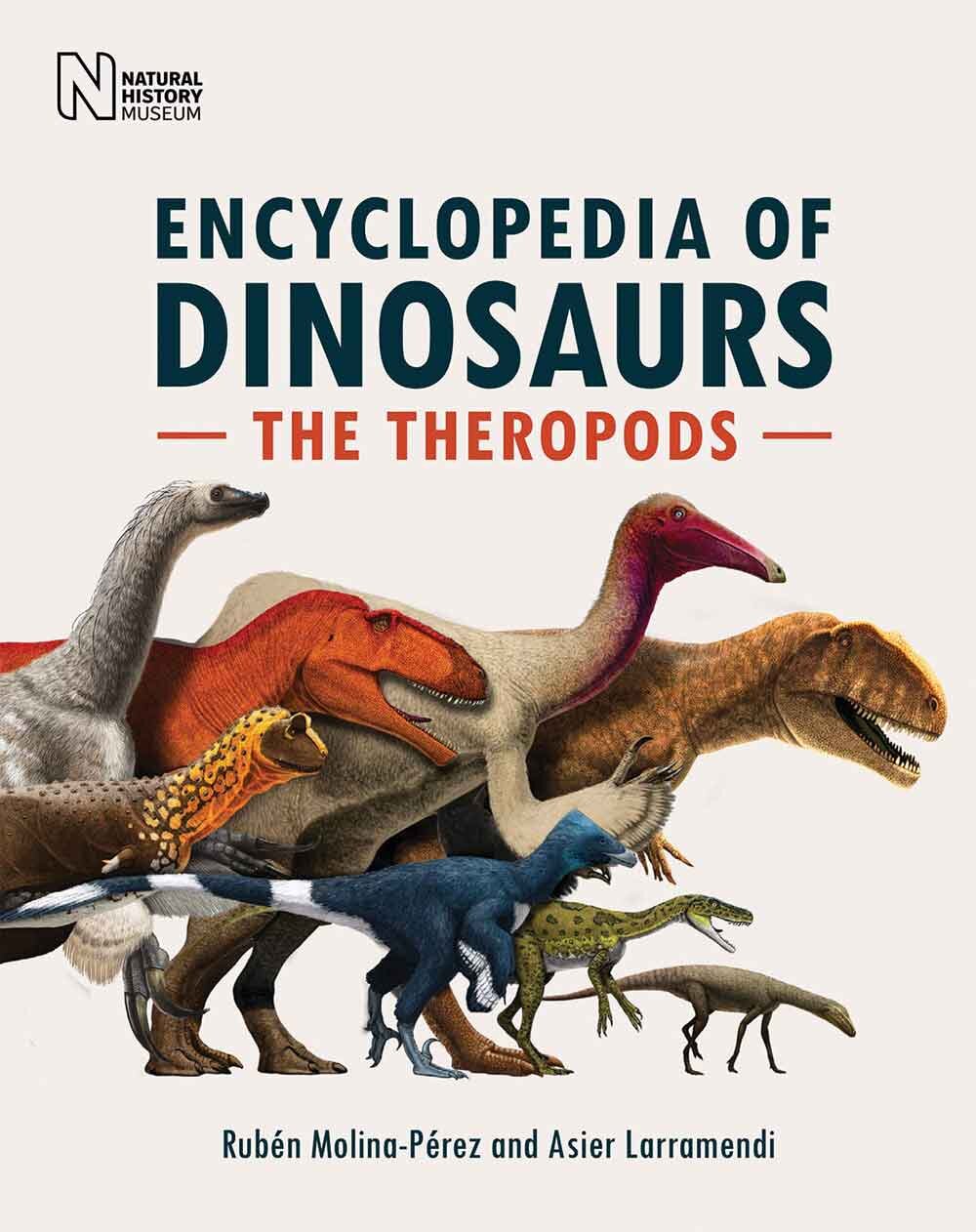

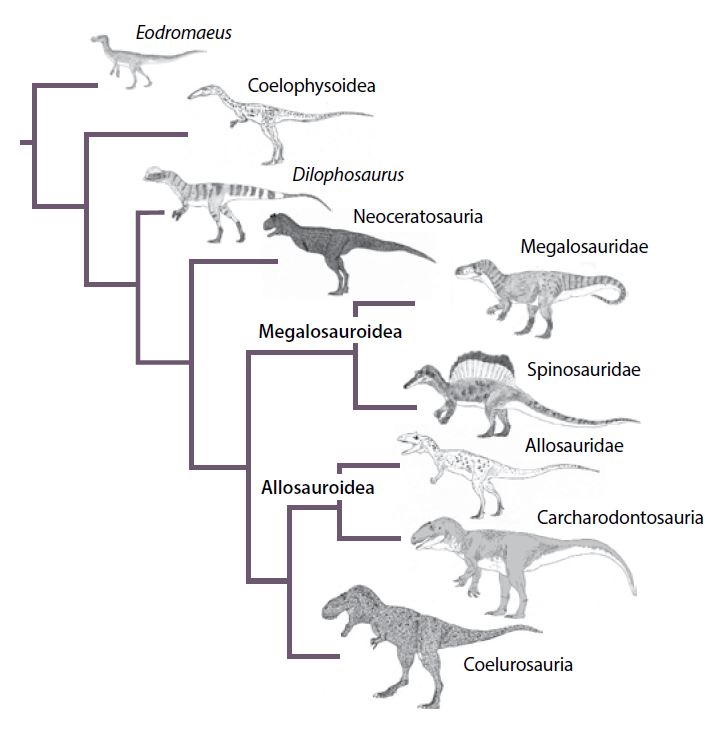

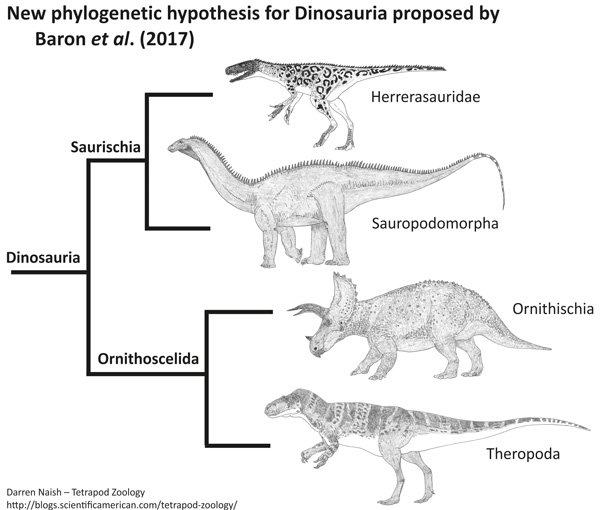

Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: the Theropods, by Rubén Molina-Pérez and Asier Larramendi

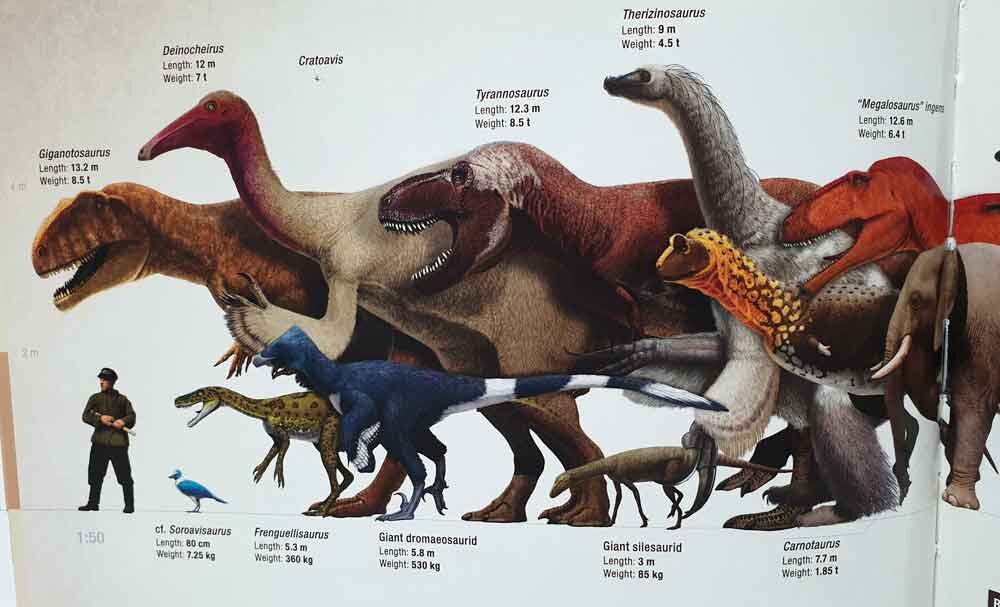

I can say right out of the gate that this 2019 work is one of the most spectacular dinosaur-themed works that has ever seen print. Think about that for a minute, since it’s a pretty grand claim. Yes. This book is spectacular: big (288 pages, and 24.5 cm x 30 cm), of extremely high standard, packed with information, and containing a vast number of excellent and highly accurate colour life reconstructions. Originally published in Spanish, it has now been translated (by David Connolly and Gonzalo Ángel Ramírez Cruz) and published in English by London’s Natural History Museum. The book consists of eight sections, which variously go through the theropod cladogram, discuss geographical regions and the theropods associated with them, and review theropod anatomy, eggs, footprints and so on. And it’s packed with excellent illustrations… hundreds of them.

A selection of pages from Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019). At left, eggs depicted to scale (with a basketball). At right, just two of the many pages that feature theropod skeletal elements. Images: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

The art is great – the majority of colour images being by the phenomenally good and reliable Andrey Atuchin – and I’d recommend that anyone interested in the life appearance of dinosaurs obtain the book for its art alone. I have one criticism of the art though, which is that the colour schemes and patterns used for some of the animals are occasionally based on those of living animals (most typically birds).

Just two of the many UNNAMED theropod species reconstructed in the book. Exciting stuff! The humans that feature in the book are an interesting lot. Images: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

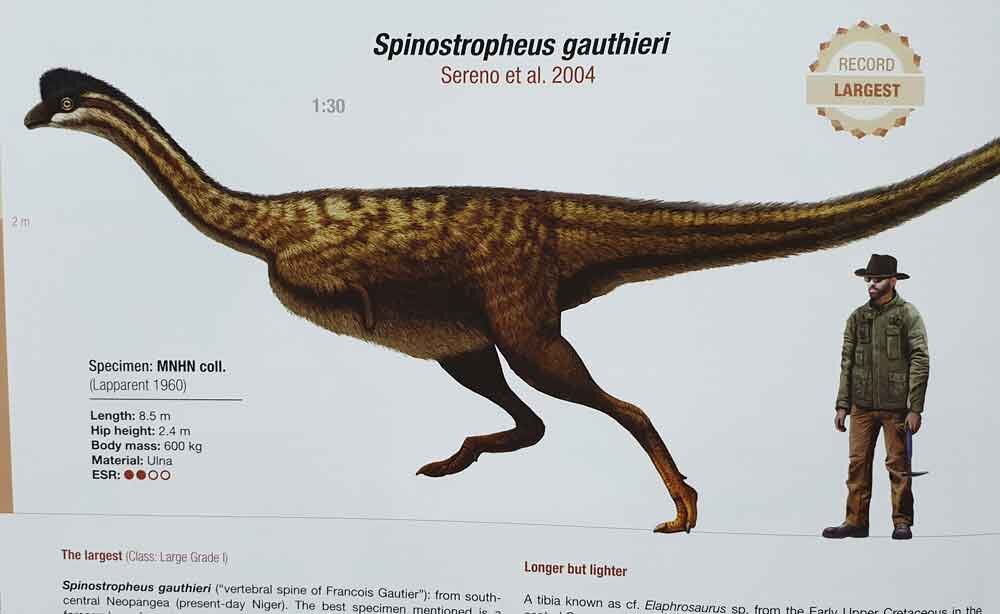

Familiar theropods of many sorts are illustrated, but a major plus point is that many of the animals depicted are either obscure and mostly new to the world of palaeoartistic depictions (examples: Spinostropheus, Dryptosauroides, Bonapartenykus, Nanantius, Gargantuavis) or are as-yet-unnamed species: animals which clearly represent something new (since they’re the only member of their group known from the relevant geographical region and segment of geological time) but have only been referred to by their specimen numbers or by a ‘cf’ attribution (a theropod called, for example ‘cf Velociraptor mongoliensis’ is being compared by its describers to V. mongoliensis and is clearly very much like V. mongoliensis, but quite possibly not part of the species and perhaps something new. The ‘cf’ is short for ‘confere’, as in: compare with).

If the reconstructions in the book are anything to go by, Spinostropheus - according to one specimen (an ulna) it could reach huge sizes - was among the most remarkable of theropods. Just look at it. Image: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

Two issues strike me as problematic though. One is that the arrangement is really difficult to get to grips with, and it’s taken me numerous attempts to understand and appreciate why the book is arranged the way it is. The second issue concerns what appears to be a suspiciously high degree of taxonomic precision for footprints. The authors depict footprints, said to be representative of the different theropod groups covered in the taxonomy section at the start of the book, and seem confident that the tracks concerned (which are often fairly nondescript) were made by species belonging to the relevant group. It’s hard to be convinced that this is reliable, except in a very few cases: I’m happy to agree that the giant Tyrannosauripus pillmorei track, for example, really was made by a member of Tyrannosauridae. Then again, maybe the authors have devised a new track identification method that isn’t yet known to the rest of us.

The several montages in the book are truly things of beauty. Image: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

And on that note, it’s obvious that a vast quantity of novel science was performed as part of the background research for this book. The methods and data used by the authors are explained up front. Impressive stuff, and stuff which should be published in the technical literature at some point. Are their results always ‘good’? Well, I have my misgivings about the idea that Dinornis the moa was the fastest (non-flying) theropod ever and capable of sprinting at a phenomenal 81 km/h…

So, so many diagrams of tracks and trackways. Image: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

Despite my minor misgivings, this book is attractive enough and interesting enough that it’s a must-have for those seriously interested in dinosaurs and in artistic depictions of them. Buy it if you can. This volume promises to be the first in a series. At the time of writing, the second of these – devoted to sauropods – is being advertised and is due to appear soon. Given that there’s every reason to assume that its artwork and overall quality will be similar to that of the theropod volume reviewed here, I have very high hopes and look forward to seeing it.

Molina-Pérez, R. & Larramendi, A. 2019. Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: the Theropods. The Natural History Museum, London. pp. 288. ISBN 9780565094973. Hardback. Here at publishers. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

Luis Rey’s Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects

Luis Rey (who blogs here) has been active in the palaeoart world for a few decades now, and most people interested in the portrayal of dinosaurs in art will be familiar with his vibrant, bold and dynamic style. Luis’s work has appeared in museum installations, exhibitions, and in numerous publications, including books. Most notable among these are his own Extreme Dinosaurs (Rey 2001) and The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs, by Robert Bakker (Bakker 2013). I feel it would be wrong at this point to avoid mentioning the fact that Luis and I were regular correspondents back when the first of those books appeared, but that my dislike of the 2013 book – which I made clear in a TetZoo review – coincided with a cessation in any contact we used to have. But things have moved on; Luis’s art has continued to evolve and let’s put all of that behind us.

A collection of Rey works at TetZoo Towers. Image: Darren Naish.

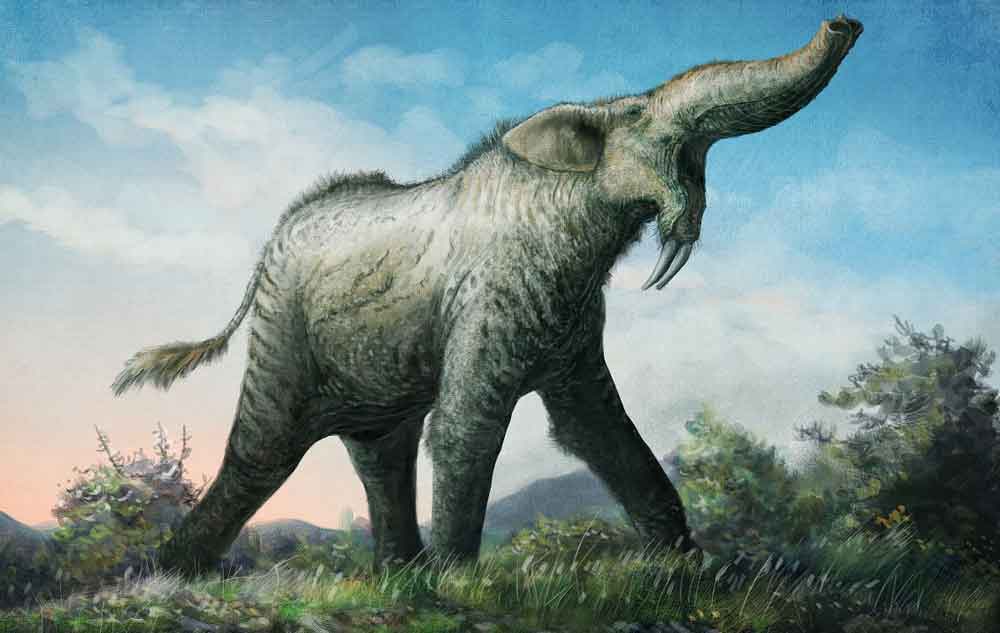

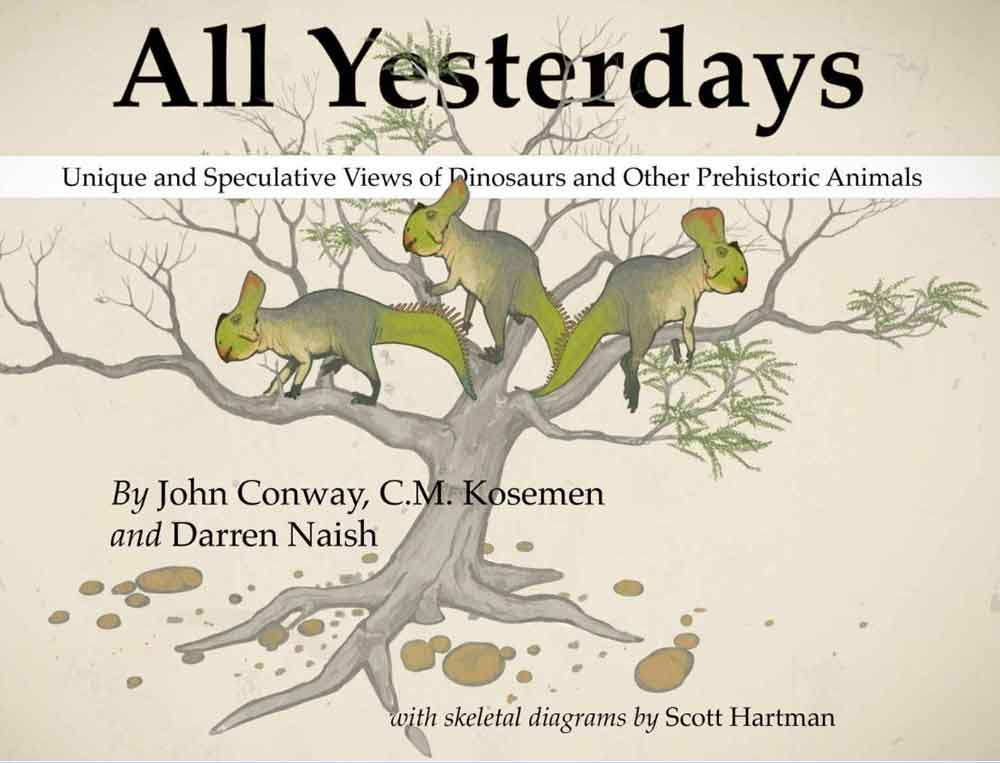

Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects discusses the intellectual and artistic background to several dinosaur-themed museum installations which Luis has created, but does so in an evolutionary fashion such that they’re used to describe our improving knowledge of the Mesozoic world. Luis was illustrating colourful, fully feathered dromaeosaurs, oviraptorosaurs and so on at a time when the majority of relevant academics were dead against this, so it would be fair to see him as one of several artists who were predicting things that would prove correct in the end. I was on side too, and consequently was a vociferous Rey advocate in the early part of my academic career, deliberately using his reconstructions of dromaeosaurs – even the turkey-wattled, shaggily feathered ones – in conference presentations and publications. And for all the success of All Yesterdays and its associated movement, we have never forgotten that Luis was saying many of the same things already.

Some representative pages from Extreme Dinosaurs 2. At right, note the person wearing an oviraptorosaur costume while sat in a nest.

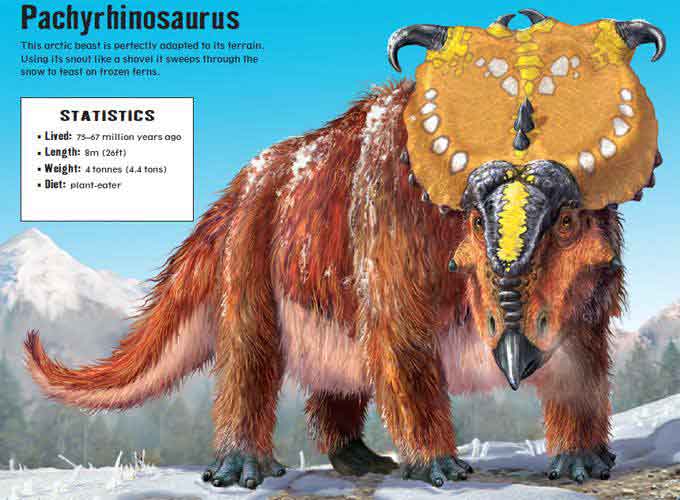

Maniraptorans, thyreophorans, ceratopsians, dinosaur eggs and nesting and the dinosaurs (and other Mesozoic reptiles) of Mexico all get coverage here as Luis explains the thinking behind new pieces of art and also how and why he’s modified older ones. Our understanding of feather arrangements in non-bird maniraptorans have improved a lot in recent years, plus we have so much new data on ankylosaur armour, ceratopsian skin and so on. If you haven’t been keeping up, this book would be a good primer. The text is concise and written in a friendly, informal style.

More representative pages, this time depicting therizinosaurs. Brightly coloured faces, bold patterns on the feathering, inflatable throat structures… what’s not to love? Image: Rey (2019).

I’m still not keen on the photo-bashing that’s now integral to the Rey style and don’t find it effective or successful. A few pieces included in the book don’t, therefore, work for me (examples: Santonian hadrosaur hassled by theropods on pp. 104-5, the Labocania scene on pp. 106-7). But can I please emphasise that I still find this a valuable book, and I very much recommend it as an interesting addition to the palaeoart stable, the autobiographical angle in particular being useful. My copy of Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects is an advance softback version but I understand that a hardback is available too.

Rey, L. 2019. Extreme Dinosaurs 2: the Projects. Imagine Publishing, London/Metepec. pp. 139. ISBN 978-0-9933866-2-6. Softback/Hardback. Here at amazon.co.uk.

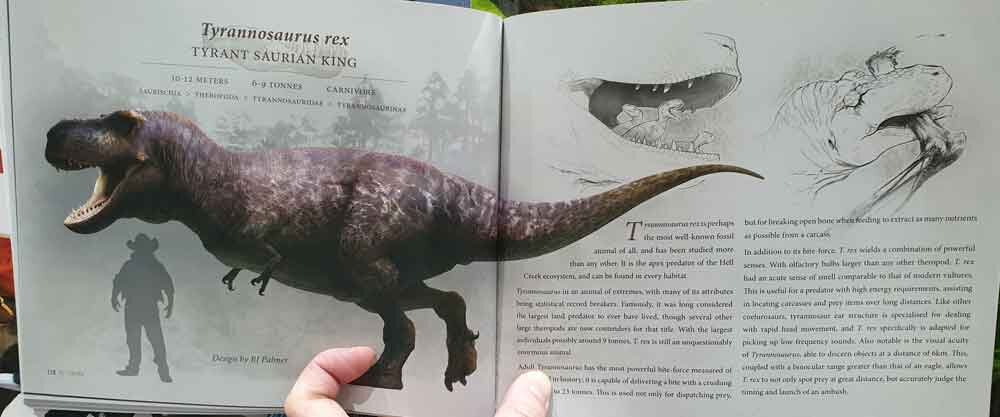

Parker et al.’s Saurian: A Field Guide to Hell Creek

Even if – like me – you’re not a video game buff and have little interest in video games or the playing of them, chances are high that you’ve heard about Saurian, a role-playing, survival simulation experience in which you play the role of a dinosaur negotiating a Maastrichtian environment modelled on that of the Hell Creek Formation. You have to avoid predators, find and procure food, raise babies, and live as long as possible. I’ve played The Simms, back in the day, and recall the urge to sink hours of time into living a virtual tiny life, so I can understand the appeal.

Representative pages, here showing the raptor prey restraint model in action. Poor pachycephalosaur. Image: Parker et al. (2019).

The relevance of Saurian to the TetZooniverse is that the game has been designed and built according to an incredibly high scientific standard, the team behind it having done a vast quantity of research on everything relevant to the Hell Creek world. And the good news is that this work hasn’t been wasted. This book – written by Tom Parker, featuring the artwork of Chris Masna and RJ Palmer (of Detective Pikachu fame and much else), and produced following consultation with a long list of relevant palaeontologists – is the result: it includes a vast quantity of amazing concept art, detailed vignettes and scaled artwork of the organisms and environments that feature in the game, and is simply a joy to look at. The text is brief but functions well. The book is a sturdy softback (20 x 24 cm) of 182 pages, printed to excellent, glossy standard.

RJ Palmer’s T. rex is one of the stars of the show. Some of you will know that the Saurian team abandoned an earlier, more feathery version. Assorted humans function as scale bars; you can likely guess who this one is based on. Image: Parker et al. (2019).

As should be clear by now, the thoroughness of the project’s world-building means that there’s more information here on Maastrichtian North American trees, rainfall patterns, swamps, beaches, amphibians, lizards, crocodyliforms, fishes and so on than you’ve ever seen before. The result is one of the most interesting, detailed and attractive volumes dedicated to Late Cretaceous life. This book is a must-have for those seriously interested in palaeoart and in seeing prehistoric animals and environments depicted in detail, but it’s also good enough that those with a scientific or technical interest in Late Cretaceous life should obtain it too.

Oh wow, so much of the art in this book is just phenomenal. This scene depicts competition among scavengers at a carcass. You might just be able to see the anguimorph lizard inside the body cavity. Image: Parker et al. (2019).

Parker, T., Masna, C. & Palmer, R. J. 2019. Saurian: A Field Guide to Hell Creek. Urvogel Games. pp. 182. Softback. Here at publishers [BUT CURRENTLY OUT OF STOCK].

That’s where we’ll end for now. A few more dinosaur-themed book review are due to appear here soon, including of Donald Prothero’s The History of Dinosaurs in 25 Fossils and Michael Benton’s The Dinosaurs Discovered: How a Scientific Revolution is Rewriting Their Story.

For previous TetZoo dinosaur-themed book reviews, see… (linking here to wayback machine versions due to paywalling and vandalism of TetZoo ver 2 and 3 articles)…

Long and Schouten's Feathered Dinosaurs, a review, January 2008

Luis Chiappe's Glorified Dinosaurs: The Origin and Early Evolution of Birds, January 2011

What they’re saying about The Great Dinosaur Discoveries, November 2011

Greg Paul’s Dinosaurs: A Field Guide, August 2012

New Dinosaur Books, Part 1: Barrett on Stegosaurs, August 2018

New Dinosaur Books, Part 2: Ben Garrod’s ‘So You Think You Know About… Dinosaurs’ Series, August 2018

The Second Edition of Naish and Barrett’s Dinosaurs: How They Lived and Evolved, November 2011

Refs - -

Bakker, R. T. 2013. The Big Golden Book of Dinosaurs. Random House, New York.

Rey, L. 2001. Extreme Dinosaurs. Chronicle Books, San Francisco.

A Review of Robert L. France’s Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent

Among the most famous sea monster cases of all time is that of the Gloucester Sea Serpent of New England, USA. This giant, serpentine creature was seen on numerous occasions between 1817 and 1824, often at relatively close range by large numbers of people, and often by people of respectable standing. Many drawings of the creatures were produced, but physical evidence of its existence was never obtained, the one relevant incident being the 1817 recovery of a small snake with a peculiar lumpy dorsal outline. This was very obviously a Black or Eastern racer Coluber constrictor afflicted with a spinal deformity.

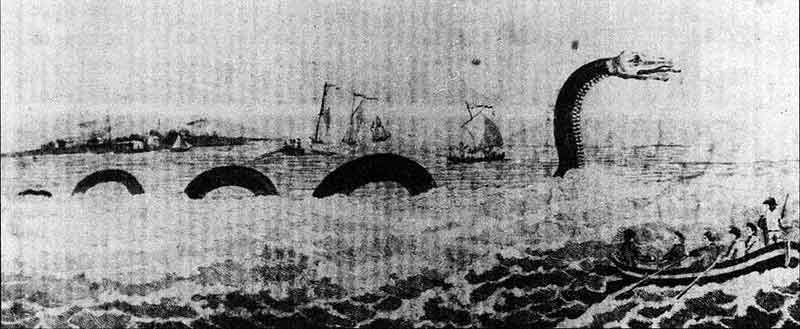

Caption: the most famous depiction of the Gloucester Sea Serpent is this fanciful one dating to August 1817, said to have been drawn from life. I don’t think the name of the artist is on record. Image: public domain.

The case of the Gloucester Sea Serpent is familiar enough that it’s covered in most works that review sea monsters and their claimed existence (e.g., Heuvelmans 1968), and indeed a few books are dedicated entirely to the creature itself (O’Neill 1999 [republished by Paraview in 2003], Soini 2010). How has the monster been identified? The opinion promoted most frequently by writers specialising in cryptozoology has been that it was a scientifically unrecognised, serpentine mammal with a series of dorsal humps arranged along its length (Heuvelmans 1968, Woodley 2008) or perhaps a giant sea reptile of the sort otherwise known only from the fossil record (O’Neill 1999).

Caption: two books dedicated to the Gloucester Sea Serpent - written for adults - are in existence, and both are worth reading. June O’Neill’s book of 1999 (though this is the cover of the 2003 Paraview edition), and Wayne Soini’s of 2010.

Robert France’s Disentangled is yet another volume dedicated to the Gloucester Sea Serpent, but it’s unlike any other. For all the popular and sensationalist interest in sea monsters, academic treatments of the subject are rare, making this book a significant addition to the literature; more so given that it was written by a qualified scientist with a substantial number of technical, peer-reviewed publications to his name. At this point I must spoil the surprise and reveal France’s primary hypothesis: that the appearance and occurrence of the Gloucester Sea Serpent was intimately tied to the economic and social history of the New England coast, and that sightings of this creature were actually of large vertebrate animals entangled in fishing gear (France 2019).

Caption: this is another especially famous depiction of the Gloucester Sea Serpent from 1817, and again it’s by an anonymous artist. The idea that the monster was seen at relatively close range is again emphasised. Image: public domain.

France on cryptozoology and cryptozoologists. What does France (2019) make of those authors who have gone before him, most of whom have been rather kind to the possible existence of sea monsters as valid zoological entities (that is, as giant marine animal species awaiting scientific recognition)? He is overwhelmingly critical of such writers, I think rightly dismissing their efforts as unscientific or, at least, as ‘bad science’. LeBlond and Bousfield’s infamous work on ‘Cadborosaurus’ (much written about here at TetZoo; see the links below) is not viewed favourably, nor is Michael Woodley’s 2008 book In the Wake of Bernard Heuvelmans (Woodley 2008). Michael (who no longer publishes cryptozoological articles; he and I co-authored some works between 2008 and 2012) has indeed promoted some unusual ideas that cannot be correct, these including that the ‘super otter’ and ‘many-humped’ sea monsters of Heuvelmans (1968) might actually be literal super-sized otters. France (2019) sees red, and describes Woodley’s writings here as “one of the most blatant displays of cryptozoological fancy” and a “ridiculous bit of science fiction” (p. 169).

Caption: books that discuss sea monster reports - here are some (albeit not all) of them - mostly interpret the relevant encounters as descriptions of giant, scientifically unrecognised animal species. Image: Darren Naish.

Henry Bauer has argued that sea monsters and lake monsters are based on reliable evidence supported by trustworthy experts, and that critics of cryptozoology are misguided and unscientific (e.g., Bauer 1982, 2002). But watch his public speaking and read enough of his articles and you’ll find that he endorses research denying a link between HIV and AIDS, and regards homosexuality as an illness. France has noticed this too and regards Bauer as a “fringe scientist” (p. 16).

As for the ‘Father of Cryptozoology’ Bernard Heuvelmans, France is highly critical, accusing him of sloppy scholarship, selective bias, manipulation of facts, an inability to identify hoaxes and misinterpretations of natural phenomena, of being “delusional at best, or outright dishonest at worst”, and of compiling “a house of cards assembled from a Trumpian world of ‘alternative facts’” (p. 30). Meurger (1988) is cited here as providing inspiration (it should really be cited as Meurger & Gagnon (1988)) but this takedown of Heuvelmans much more recalls Ulrich Magin’s critique (Magin 1996), paraphrased in Hunting Monsters (Naish 2017). I’ve even specifically likened the cryptozoological literalism of Heuvelmans and his followers to a house of cards, but I don’t doubt that this use of allegory could be coincidental. Cryptozoological classification schemes – the meat-and-potatoes of works by Heuvelmans, Coleman and Huyghe, Woodley and others – are described as a ‘nomenclature of nonsense’ by France (2019, p. 165).

Caption: the most influential sea monster book of them all is Heuvelmans (1968). Therein, he argued for the existence of nine distinct sea monster types, illustrated at left by Cameron McCormick. Their purported existence hasn’t exactly been embraced by biologists at large. Images: Cameron McCormick, Heuvelmans (1968).

When it comes to those who’ve been critical of cryptozoological literalism, France is quite the fan. Konar (2009) – an article I cannot claim to know – is cited and discussed since its author argues that cryptozoology is a pseudoscience. France writes favourably of Michel Meurger’s argument – promoted most famously in Meurger & Gagnon (1988) – that efforts to interpret the creatures of myth, folklore and anecdote as valid undiscovered animal species miss the point (“aquatic cryptids are ‘real’ only in the sense that they are mental constructs that have their origin in folklore and exist within a mythological landscape”; France 2019, p. 33), and he likes Daniel Loxton and Don Prothero’s Abominable Science (Loxton & Prothero 2015) and cites it frequently.

My own writings on sea monsters and cryptozoology in general are abundantly cited and fairly credited but mostly in a single paragraph on page 32 rather than scattered throughout the text as might seem appropriate. This (perhaps falsely) creates the impression that France only discovered my writings late in his project and opted to crowbar them in somewhere, but no matter.

After all this, what does France make of cryptozoology overall? Does it have value, has it been mis-framed, or is it just a pile of shit? I found France’s take on this issue difficult to parse and inconsistent. Despite strong agreement with those who argue that the study of cryptids is more to do with a sociocultural interpretation of the world, France argues in part of the book that it should be regarded as “an anachronistic form of natural history” (p. 35). He takes time to dismiss the notion that cryptozoology might be considered part of ecology. Which is odd, because surely the identification of entities reported via anecdote and observation is very obviously not ecology (assuming that ‘ecology’ relates to the study of how organisms relate to their physical surroundings) but instead more to do with systematics, biodiversity monitoring and/or social anthropology and folklore. Indeed, if the bulk of the cryptozoological literature involves the collecting of anecdotes about things implied or believed to be animals, and the evaluation of these anecdotes such that flesh and blood animals can be ‘shown’ to be at the bottom of the reports, we’re not talking about natural history or ecology but ethnozoology. France ends Chapter 1 with a hearty endorsement for the value of ethnozoology as a valid field of study, the takehome being that what people have been calling cryptozoology is ethnozoology.

The entanglement hypothesis. Introduction out of the way, France devotes the next section of the book to the 19th century ‘eco-cultural seascape’ of the North American eastern seaboard, covering the region’s geography, economy and cultural history. A classical and biblical background gave the region’s European colonists a belief system whereby elongate, unidentified marine objects (France uses the acronym UMO throughout the book) might be interpreted as gargantuan marine serpents, and some appropriate section of text is devoted to 19th century fishing methods and the technology employed. This looks on initial reading like an aside but is crucial for the argument that France (2019) later compiles, this being that entanglement explains the sea monster sightings.

But waitaminute – isn’t entanglement with marine debris (‘ghost gear’ and so on) a modern issue, linked to the use of modern fishing materials? No. It turns out that fishing gear has been lost or dumped at sea for as long as people have been making such things, that animals large and small have been becoming entangled in lost or dumped fishing gear since forever, and that seafaring people have been aware of this issue but have not had cause to report it, or have wilfully under- or unreported it, since time immemorial. Entanglement is a pretty horrible thing. Individual animals can remain bound in or connected to debris for literally years, and both old and modern materials used in fishing are made of materials that persist for decades and, potentially, centuries. As France (2019) shows via his analysis of Gloucester Sea Serpent reports, people’s descriptions of the UMOs concerned pertain to animals entangled in ropes, or swimming while connected to floats, buoys, barrels, kegs or netting. I found his case compelling.

Caption: some, perhaps many, of the sea monsters endorsed at times by cryptozoologists now need to be reinterpreted as observations of known animal species entangled with marine debris. Among them is the supposedly tadpole-like ‘yellow belly’ of Heuvelmans (1968). This imagined creature has been discussed at TetZoo on several occasions over the years. Images: Heuvelmans (1968), Darren Naish, Tim Morris.

By now it will be obvious why the book has the title that it does. Disentangled refers not only to the fact that entanglement with fishing gear explains many, most or all of the sea monster accounts relevant to the Gloucester case, but also that France (2019) has succeeded in disentangling the strands of a story that hasn’t previously been understood. Is this definitely so, though?

In view of the drubbing that cryptozoological literalists receive throughout France’s book, it’s ironic that Heuvelmans (1968) was the first to propose the entanglement hypothesis. In attempting to interpret a sea monster seen in Cape Town Harbour in 1857, and reported by a Dr François Biccard and seven other observers, Heuvelmans (1968) wrote that “This so-called body is so unlike any part of an animal that one cannot help thinking that it may have been a net or rope towed by a shark or [France has ‘of’ here] porpoise which had got caught in it and whose wounded body appeared to be what the doctor called the head” (Heuvelmans 1968, p. 242). But, alas, poor Bernard, here “Demonstrating a degree of perceptive reasoning markedly absent from the rest of his tome…” (France 2019, p. 194). Damned with faint praise. Incidentally, France (2018) has written a whole paper on the Cape Town Harbour case and its significance.

Caption: Biccard’s illustration of the 1857 sea monster (or UMO) seen from Table Bay, Cape Town. There weren’t two monsters - the picture shows two views of the same object. Heuvelmans (1968) was unable to place this creature within any one of his nine sea monster categories. Image: public domain.

But if the Gloucester Sea Serpent (and at least some other sea monsters too) really was an animal entangled in lost or discarded fishing gear, what specific animal are we talking about? France (2019) eliminates whales for various reasons and favours the view – in part based on the swimming speed of the monster, its ability to make extremely tight turns and its propensity to frequent very shallow water – that the most likely candidate was the Bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus. “Most likely”? Is that the best we can do? The fact that the monster’s true identity can’t be precisely determined and remains unresolved is slightly awkward given France’s (2019) determination earlier in the book that cryptozoology is unsatisfyingly unspecific, and France readily admits this. But as a committed advocate of the notion that providing a provisional or ad hoc scientific conclusion is by no means problematic, I don’t see an issue.

Caption: tuna are remarkable fishes, and France (2019) emphasises how incredible they are. Strong, fast, and surprisingly big (this life-sized model - formerly on show at London’s NHM - is about 2 m long), they might help explain the Gloucester Sea Serpent UMO. Image: Darren Naish.

Yes, I agree with Robert France that entangled marine vertebrates are the real explanation behind some, if not many, sea monster sightings… or UMOs, if you prefer… and specifically those associated with Gloucester Harbour, Massachusetts. I’m slightly embarrassed not to have noticed this earlier. But, then, to reach this conclusion and write authoritatively about it requires not only a familiarity with the sea monster literature and cryptozoological lore but also with the anthropology, economy and industry of North America’s eastern seaboard, and few of us have been focused enough, or expert enough, to do that. Professor France, I raise my glass.

Caption: the entanglement hypothesis doesn’t mean that all ‘sea monster’ reports describe animals that can be interpreted in the same way: some accounts are, more likely, just misidentifications. One example mentioned by France is that of the ‘baby Cadborosaurus’, reinterpreted by myself and colleagues in 2011 (Woodley et al. 2011). Image: Woodley et al. (2011).

A few statements and proposals made in the book are objectionable and might be deemed wrong by a reader with specialised knowledge. The idea that the Spicer land sighting of the Loch Ness Monster was inspired by a scene in King Kong (mentioned favourably by France on p. 32) has experienced something of a pushback recently and should not be mentioned as if we know that it actually happened. France also refers to the kraken as if it’s the same thing as Architeuthis, the giant squid. This notion, while still popular, is not consistent with evidence (Paxton 2004, Naish 2017). Tim Dinsdale’s famous Loch Ness film of 1960 is not “waves plus a little imagination”, as France states (p. 181), but a boat. It is also wrong to state that lake monsters (like the Loch Ness Monster) are “known to [be] misidentified natural phenomena” (p. 173) and to cite ‘Binns 2017’ as if this is what Binns (2017) is all about: sure, misidentified natural phenomena have contributed to belief in lake monsters, but they don’t provide ‘the’ explanation given that there are lake monster sightings that involve known animal species, boats and so on. Binns (2017), incidentally, was reviewed here at TetZoo.

A curious aside concerns a case irrelevant to France’s entanglement hypothesis, this being Captain Hanna’s mystery fish of 1880. Hanna’s fish has variously been considered a mysterious long-bodied chondrichthyan (Heuvelmans 1968), a possible new species of long-bodied teleost (Roesch 1997; though note that a modern Ben Speers-Roesch does not support this idea) or an oarfish. France (2019) considers the last of these suggestions correct, the fish being “clearly recognizable” as a member of this species (p. 241). In the same section of text, France also notes that Frilled sharks Chlamydoselachus anguineus are sufficiently monster-like that a sighting of a live one near the sea surface “would be all that it would take to raise the cry of ‘sea serpent!’” (p. 242). More exciting is that France (2019) takes seriously the suggestion (made in an online 2015 National Geographic article) that “an 8 metre-long related animal was caught in 1880” (p. 242), the implication being that giant frilled sharks might be out there and awaiting discovery. That’s not altogether ridiculous given the recent discovery that Goblin sharks Mitsukurina owstoni - long assumed to not exceed 1.5 metres in total length - have been shown to sometimes exceed 6 metres in total length (Parsons et al. 2002). But there’s some confusion here: the 1880 ‘related animal’ is one and the same as Captain Hanna’s mystery fish!

Caption: S. W. Hanna’s sketch of the giant mystery fish - 7.6 m long - captured in a net off New Harbor, Maine, in 1880. Most books on sea monsters mention or discuss this animal, most frequently with the (frankly very silly) idea that it might have been a giant serpentine shark. Image: public domain.

My biggest gripe concerns the book’s editing. Alas, this otherwise fine and well-designed book does not appear to have been thoroughly proofed, for conspicuous and often amusing typos abound. Among those I spotted are ‘Huevelmans’ (p. 30, for Heuvelmans), ‘by his by living’ (p. 34, for ‘by his living’), ‘gapping mouth’ (p. 63, for ‘gaping mouth’), ‘sheds her objectively’ (p. 90, for ‘sheds her objectivity’), ‘as to creature’s identity’ (p. 92, missing ‘the’), ‘crypotozoologists’ (p. 141), ‘flour legs’ (p. 161, for ‘four legs’!), ‘pinnepeds’ (p. 169, for ‘pinnipeds’), ‘in in 1809’ (p. 184), ‘Prionace glavca’ (p. 227, it should be P. glauca), ‘more than a three hundred m’ (p. 227), ‘odentocetes’ (p. 228, for ‘odontocetes’), ‘merebeing’ (p. 265, for ‘merbeing’), and ‘preciously here’ (p. 246, for ‘precisely here’). I have to add that the lack of an index is a major and surprising weakness.

Oh, one final complaint, and it’s one that, regretfully, I so often voice in my book reviews: this book is phenomenally expensive. It’s £50 in the UK, €68 in continental Europe, and $77 in the USA. As per usual, the argument here - I suppose - is that it’s meant for institutions and their libraries, and not for individual researchers. Huh.

Caption: France (2019), one of the most important volumes now published on sea monsters, and certainly the most technical. Image: Darren Naish.

These issues aside, Disentangled, then, is a thoroughly worthy and interesting book, and those seriously interested in sea monsters, anthropological use of the sea, marine folklore and marine ecology and pollution should read it. The book itself is dense, with small print and copious black and white illustrations, and I like its design. With the publication of this book, we have entered a new era in our understanding of sea monsters and every subsequent work on the subject will have to cite and mention it. And it is a sad indictment on our species, on our impact on the planet and its other animal species, that the solution to what was long deemed one of nature’s greatest mysteries is resolved as but a deleterious consequence of our unthinking, wasteful and harmful ways.

France, R. L. 2019. Disentangled: Ethnozoology and Environmental Explanation of the Gloucester Sea Serpent. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, The Netherlands. pp. 289. ISBN 978-90-8686-335-8. Softback. Refs. Here at publishers. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

For previous TetZoo articles on sea monsters (and lake monsters too), see… (reminder: articles at ver 2 and 3 are mostly ruined by hosting issues)…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

A baby sea-serpent no more: reinterpreting Hagelund’s juvenile Cadborosaurus, September 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

The Cadborosaurus Wars, April 2012 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013 (now stripped of all images, so completely useless)

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014 (now stripped of all images)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Usborne’s All About Monsters, April 2019

Sea Monster Sightings and the ‘Plesiosaur Effect’, April 2019

Refs - -

Bauer, H. H. 1982. The Loch Ness monster: public perception and the evidence. Cryptozoology 1, 40-45.

Bauer, H. H. 2002. The case for the Loch Ness “monster”: the scientific evidence. Journal of Scientific Exploration 16, 225-246.

Binns, R. 2017. The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded. Zoilus Press.

France, R. L. 2018. Illustration of an 1857 “sea-serpent” sighting re-interpreted as an early depiction of cetacean entanglement in maritime debris. Archives of Natural History 45, 111-117.

Heuvelmans, B. 1968. In the Wake of the Sea-Serpents. Hill and Wang, New York.

Konar, G. 2009. Not your everyday animals: applying Occam’s Razor to cryptozoology. The Scienta Review, MIT.

Loxton, D. & Prothero, D. R. 2013. Abominable Science! Columbia University Press, New York.

Magin, U. 1996. St George without a dragon: Bernard Heuvelmans and the sea serpent. In Moore, S. (ed) Fortean Studies Volume 3. John Brown Publishing (London), pp. 223-234.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters. Arcturus, London.

Parsons, G., Ingram, G. W. & Havard, R. 2002. First record of the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni, Jordan (Family Mitsukurinidae) in the Gulf of Mexico. Southeastern Naturalist 1 (2) 189-192.

Paxton, C. G. M. 2004. Giant squids are red herrings: why Architeuthis is an unlikely source of sea monster sightings. The Cryptozoology Review 4 (2), 10-16.

Roesch, B. S. 1997. A review of alleged sea serpent carcasses worldwide (part one – 1648-1880). The Cryptozoology Review 2 (2), 6-27.

Soini, W. 2010. Gloucester’s Sea Serpent. The History Press, Salem, Massachusetts.

Woodley, M. A. 2008. In the Wake of Bernard Heuvelmans. CFZ Press, Bideford.

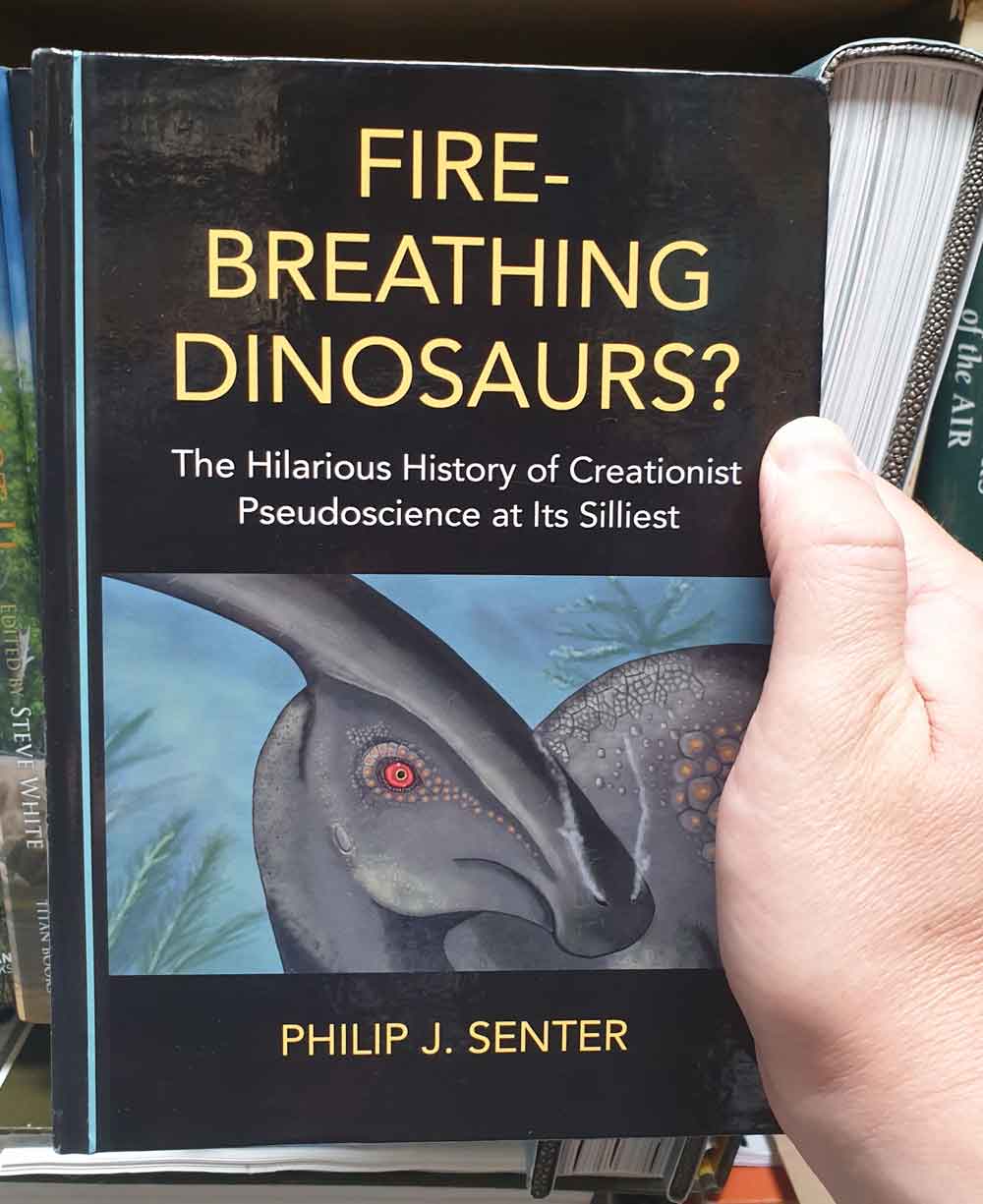

Philip J. Senter’s Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs?, the TetZoo Review

Many of us interested in the more arcane side of natural history will be aware of that body of literature that seeks to explain the biology, behaviour and history of living things within the words of a complex, multi-authored work known as The Bible. I refer of course to the creationist literature; to that number of books and articles whose authors contend that animals known from fossils simply must accord with the stories and descriptions of the Bible, and whose authors furthermore contend that the Earth and its inhabitants must have come into being within the last few thousand years.

Caption: a smouldering Parasaurolophus: the cover art for the book, by Leandra Walters. Image: (c) Leandra Walters/Senter (2019).

Creationist authors – the most familiar include Ken Ham, Kent Hovind and Duane Gish – have argued that non-bird dinosaurs and other fossil animals were inhabitants of the Garden of Eden, that predatory species like Tyrannosaurus rex ate water melons and sugarcane before The Fall, that humans and animals like Tyrannosaurus lived alongside one another during the early days of the Earth’s creation, that evolution cannot have happened, except when it did as species emerged from their different ancestral kind (or baramins), and that animals like Tanystropheus, tyrannosaurs and pterosaurs were seen and written about by people, and are responsible for the mythological creatures mentioned or described in the Bible and other ancient texts. Leviathan and Behemoth of The Bible, Grendel of the medieval epic Beowolf, the fire-breathing dragons of the Middle Ages and so on must – creationist authors contend – be descriptions of human encounters with giant reptiles otherwise known as fossils. And, yes: you read that right… creationist authors have argued, apparently seriously, that fire-breathing dragons must be descriptions of encounters with animals like dinosaurs and pterosaurs. So… they… breathed fire, then.

Caption: the Bible specifically states that the first few books of the Old Testament are not meant to be taken literally. Despite this, a number of Young Earth creationists promote a view of the ancient world where people lived alongside allosaurs and pterosaurs and so on. If you’ve seen a version of this page mentioning lemonade and homosexuality, it’s a spoof (the original text does not include that section of text). Image: (c) Ken Ham, Dinosaurs of Eden.

Over the past several years, Fayetteville State University biologist and palaeontologist Philip J. Senter has published a great many technical scientific articles evaluating the various claims and models of creationist authors; some of his articles are short-form versions of the text included in this new book (cf Senter 2017). His approach is to accept their proposals as valid scientific hypotheses, and not to knock, mock or discount them out of hand from the start. Remember that point; we’ll be coming back to it. This approach means that creationist claims can be considered tested in the empirical sense. It should also be noted that Senter is an Orthodox Christian with qualifications in theology, so his sympathetic and scientifically ‘honest’ approach to creationist claims should not and cannot reasonably be taken as any sort of attack on the Christian faith that the relevant creationists are part of. The fact that Senter is himself religious mean that he can make the argument (should he wish to) that the bad calls and bs put out by creationists is not just ‘bad science’ but ‘bad religion’, too. I’ve heard the same argument from other scientists who maintain an active religious life.

Caption: the book reviewed here is not the first time Senter has written about the ‘fire-breathing dinosaurs’ idea. Image: (c) Skeptical Inquirer.

For completion, and for those who don’t know, I should add that Senter is also an experienced and prolific author of studies devoted to more conventional palaeontological fare: descriptions of new dinosaur species, analyses of phylogenetic patterns, interpretations of functional morphology, and so on. The technical papers of his that I’ve found most useful and interesting include Senter et al. (2004) and Senter (2007) on dinosaur phylogeny, Senter (2006, 2009) on palaeobiology, and Senter (2005), Senter & Robins (2005), Senter & Parrish (2005) and Bonnan & Senter (2007) on dinosaur functional morphology.

Caption: the handsome cover of Senter (2019).

The early chapters of this book evaluate and discuss the creationist contention in general and the relatively young history of the entire movement. The impact of John Whitcomb and Henry Morris’s 1961 book The Genesis Flood is obvious, as is the fact that their arguments fail evaluation (Senter 2019). Nevertheless, their influence was such that – from the early 1970s onwards – a number of like-minded individuals were promoting Whitcomb and Morris’s vision, and were in particular arguing that ancient and medieval writings and works of art make explicit reference to dinosaurs and other long-extinct animals. Senter (2019) uses the term apnotheriopia (meaning ‘dead beast vision’) to describe the tendency of creationist author to interpret monsters in literature and art as long-extinct reptiles.

If apnotheriopia is one of your guiding principles, it ‘follows’ that the fire-breathing dragons canonical to Eurocentric, Christian mythology should be interpreted as dinosaurs or similar reptiles, and that such creatures were dragonesque fire-breathers. So integral has the whole fire-breathing thing been to these authors that they’ve proposed fire-breathing for dinosaurs of several sorts (most frequently hadrosaurs) as well as for pterosaurs and the giant Cretaceous crocodyliform Sarcosuchus (Senter 2019). You might know of one or two cases in which this idea has been mooted. Senter’s book shows that numerous authors have engaged with this vision and written about it. The sheer quantity of this literature is daunting – I was going to say ‘impressive’ but this absolutely seems like the wrong word – and Senter has clearly gone to some considerable trouble to obtain it. He must own a pretty hefty personal library of creationist volumes, and I’m reminded of a statement he makes in one of his papers, wherein he notes that collecting and reading creationist literature on dinosaurs and other extinct animals is one of his “guilty pleasures”.

Caption: some creationist authors have argued that certain dinosaurs could have functioned just like the living bombadier beetles AND SPEWED FIRE!!!!1! One minor issue: bombadier beetles don’t spew fire, they eject hot liquid. Image: Patrick Coin, CC BY-SA 2.5 (original here).

Indeed, the bulk of this book – the long section that runs from chapters 5 through 15 – is a chapter by chapter analysis of the different fire-breathing claims made by creationist authors. These people have, I’ve been surprised to learn, come up with six different mechanisms for fire production in extinct archosaurs. Senter (2019) goes through each in turn, in appropriate detail. In some cases, the proposed mechanisms are total non-starters (no, dear creationists, pterosaurs couldn’t house flammable gases inside their head crests) and can be brushed aside quite swiftly. But in other cases, Senter (2019) has to go down the rabbit-hole of gas chemistry, anatomy and biochemistry, and the history of burns and gaseous explosions in human medicine. All fascinating and well-argued stuff, and full of amazing nuggets of information.

Caption: Parasaurolophus - beloved posterchild of the fire-breathing dinosaurs movement - flames an anachronistic Ceratosaurus, a familiar image from the creationist literature. I believe that this is from one of Ken Ham’s books.

The conclusion, overwhelmingly, is that creationists have been spouting ill-informed (or uninformed) nonsense in coming up with their various fire-breathing fantasies. The proposals concerned are inconsistent with biology, chemistry and physics, and cannot have been present in animals governed by the rules that apply to the living things of planet Earth.

Caption: it’s well known that the crests of lambeosaurine hadrosaurs were hollow, and contained connected internal tubes and chambers. Were these used in the production of fire? No. Image: Sullivan & Williamson (1999).

The book’s final two chapters are connected to the fire-breathing creationist movement, but tackle rather different topics: the origin of dragons as a whole, and the true identity of the biblical Behemoth (Leviathan is covered too), often said by creationists to be a description of a sauropod or similar dinosaur. These two chapters are among the most interesting and valuable in the book.

Caption: why have creationists been so big on the ‘dragons were fire-breathing dinosaurs’ thing? I think it’s partly an effort to attract children to their cult. It isn’t coincidental that most illustrations of fire-breathing dinosaurs appear in books written for children, like this one by Duane Gish.

Even today, the notion that dragons must surely have been based on giant reptiles or reptile-like animals still unknown to science is not unpopular, and is occasionally promoted in the cryptozoological and conspiracy literature. But it’s wrong: the whole idea of dragons as we mostly imagine them (winged, fire-breathing, horned monsters, clad in armour-like scales and equipped with massive limbs and talons) is a mistake, and one that emerged, incrementally, from more mundane origins.

Senter (2019) shows, via statements made in antiquarian literature and by cross-referencing their use of terms, that the term dragon was used – unambiguously, consistently and repeatedly – for snakes, especially for large kinds like pythons. Yes, dragons were snakes. But how does this explain the limbs, wings, fire-breathing and other embellishments? These were added over time, mostly by medieval European authors who were no longer familiar with giant snakes and had heard rumours that dragons could fly (Senter puts this unfamiliarity down to the rise of Christianity and the closing of pagan temples). Feathered wings were added during the 8th century, which then became membranous wings thanks to inventive artists. By the 13th century, dragons were being depicted as quadrupeds (Senter 2019). What about the fire-breathing thing? If dragons were snakes, then some dragons were venomous, and capable of creating a burning sensation in human tissue. Embellish and augment this idea sufficiently, and the concept of fire-breathing winged mega-snakes has emerged. Chinese dragons, by the way, have an entirely independent origin and were mostly based on mammals; Senter (2019) even says that they shouldn’t be called dragons.

Caption: in this most famous depiction of Leviathan - that by Gustave Doré, dating to 1865 - Leviathan is depicted as a monstrous winged serpent of the seas. Image: public domain (original here).

Finally, Senter (2019) also shows – I think convincingly – that the creationist interpretations of both Leviathan and Behemoth of the book of Job are entirely erroneous, but so are the interpretations favoured by the majority of sceptical and ‘mainstream’ authors. I don’t want to steal all of Senter’s thunder, but… Leviathan and Behemoth were both gargantuan mythical serpents, and those authors who have interpreted these creatures as dinosaurs, crocodiles, or big mammals have misunderstood key descriptive phrases, or have been led astray by mistranslations or misinterpretations of the original Hebrew (Senter 2019).

Caption: Senter (2019) uses cartoons like this one to emphasise that Behemoth never was a dinosaur, elephant or hippopotamus, but “a demonic entity that the ancient Hebrews envisioned as a serpent” (Senter 2019, p. 142). The caption to this illustration is “Will be real Behemoth please stand up?”. Image: Senter (2019).

This book is not that lengthy. There are 201 pages, but 45 of them are occupied by a very voluminous bibliography. Plus the book is hardback (or, this edition is, anyway), so appears bulkier than it would do with soft covers. It’s well illustrated and includes numerous colour photos, diagrams of many sorts, and colour cartoons explaining and depicting Senter’s responses to creationist proposals and arguments. There are two things about the images that I dislike. Firstly, some of the colour photos chosen to depict given extinct taxa are quite anachronistic: things would be improved, I feel, if more contemporary reconstructions took their place. Secondly, the colouring used for many of the cartoons is less than great. I mean, the cartoons themselves – which I assume Senter penned himself (he’s a pretty good and competent artist) – are great, but it looks like they’ve been coloured-in with colouring pencils.

Caption: need to feature a depiction of an extinct animal? I, personally, would prefer it if a more up-to-date and aesthetically pleasing image were used in place of this one. Senter (2019) uses several images of models similar to this one when discussing extinct taxa. Image: I’ve been unable to find a source for this picture; it comes from that bottomless pit of hell called pinterest.

So far I’ve been kind to this book. I enjoyed reading it and think it’s a worthy addition to the literature. But I’m afraid that, by the time I’d finished reading it, I’d taken quite a disliking to it, for three reasons.

The first thing I dislike is the way in which creationist claims and proposals are framed. I’m not exactly a fan of creationism, creationist arguments or creationists themselves and I certainly agree with Senter (2019) that the authors who’ve pushed creationist agendas have been scientifically clueless, and/or have sought to wilfully promote anti-scientific gas-lighting. Senter (2019) even finishes the book with a prayer, praising creationist authors for their dogged promotion and energy but wishing and praying that they might make the world a better place by re-directing their energies to something good or constructive. Fair enough.

I do think, however, that Senter (2019) overdoes it in framing creationists and their ideas as ‘silly’ and ‘ridiculous’; Senter (2019) does this throughout the whole of the book such that its entire approach is “let’s all laugh at those whacky creationists” (the subtitle, I’ll remind you, is The Hilarious History of Creationist Pseudoscience at its Silliest). In my opinion (I’d be interested to know if others agree), the book would have worked better if Senter’s approach throughout was neutral and without the mocking. I’ve mocked creationists myself, for sure (Naish 2017), but I’m not about to write an academic book on the subject of their writings. Indeed, given that I’m familiar with Senter’s many papers where he tests creationist claims (all are written in scholarly fashion and use language and phrasing typical for peer-reviewed science), I was surprised to see him follow this path, and I had the impression throughout that it was done in an effort to make the text lighter, more fun, and more appealing. I understand the need for that but I’m saying that – surely – there must have been another way.

Caption: Senter (2019) compares creationist decisions to those made by a character called ‘Silly Chef’ (the muppet-like individual in the middle) who features in a series of cartoons that appear throughout the book. Image: Senter (2019).

Finally on this point, it might be doubtful that the creationists and would-be creationists who are the focus of Senter’s (2019) discussion will ever read this book (it’s abundantly clear that they don’t, or haven’t, read any of the other literature criticising or demolishing their arguments; if they have, they do a good job of making it appear that they haven’t). But by framing the entire book as a “let’s all laugh at those whacky creationists” exercise, the people who might benefit most by reading it will (I assume) be thoroughly put off. Admittedly, this is a moot point anyway in view of my third negative point, but hang on, we’ll get to that in a minute.

The second thing I dislike concerns Senter’s use of humour. This book is well written, and well edited too (I didn’t spot a single typo). But the prose is ruined by Senter’s repeated, very weird forays into simile and metaphor. They are, I’m sorry to say, not just bad, but among the worst examples of writing I can recall. Not only did I not ever find his quips funny, I mostly found them tortuous and daft and I winced every time the text introduced yet another one. I feel bad for saying this and apologise for seeming like a miserable bastard. I disliked this stuff so much that I feel the book would be much improved if all of it was stripped out. And if you’re thinking that – surely – the relevant sections of text can’t be all that bad. Well, here’s one example…

“The misunderstandings and mistranslations necessary to force such an interpretation are almost as bad as those that would be required to infer that the story of David killing Goliath is about a vampire grapefruit preparing a pleasant pile of purple petunias as a fluffy pillow for the happily napping saber-toothed tiger that it keeps as a pet and is convinced for no apparent reason that it is a gigantic German bunny with adorable tiny little ears that wiggle ever so preciously when you gently blow into them” (Senter 2019, p. 144).

There are many other examples of this sort of thing. They ruin the book.

Finally, the third thing I dislike is that great bane of book-buyers from impoverished backgrounds: the price. This book is absurdly expensive; ridiculously so. It’s £69.99 in the UK, $119.95 in the USA (though Amazon is currently selling it at a mere $71.89). As per usual, I appreciate that publishers have to sell books at a given price to cover production costs and to compensate for a sometimes distressingly low number of sales, but I still don’t understand why a slim volume has to cost as much as this one does. Given the price, I fully expected this to be some thick, extremely heavy textbook of perhaps 700 pages or so. But no, it’s a small book of no greater size, production value, academic quality or paper thickness than a great many books half its price or less. I’m extremely pleased to have obtained a review copy but that’s the only way I could ever have obtained it. There is no way I would have purchased it. If a paperback version appears and is reasonably and affordably priced, I apologise for this complaint and may even come back to this review and remove this entire paragraph, but let’s see.

Caption: Senter (2019) is not a big book. Here’s a copy with my hand for scale. Image: Darren Naish.

Caption: I was expecting a much, much larger book. Image: Darren Naish.

I apologise for ending on such a downer.

Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs is certainly a unique book, and – as someone familiar with Senter’s writings on the creationist literature – it does have a magnum opus, end-of-the-road feel about it. As I’ve stated in this review, it’s well-written, has very high production values, and is of significant interest to those who follow the esoteric literature on Mesozoic archosaurs, and on the history of religiously motivated pseudoscience. But it has issues.

Senter, P. J. 2019. Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs? The Hilarious History of Creationist Pseudoscience at Its Silliest. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle Upon Tyne. pp. 201. ISBN 978-1-5275-3042-3. Hardback, refs, index. Here at amazon, here at amazon.co.uk, here from the publishers.

A few other reviews of Fire-Breathing Dinosaurs? are online. I deliberately didn’t read them until completing my own review. Having now read them, I see that they make similar points to my own…

Refs - -

Bonnan, M.F. & Senter, P. 2007. Were the basal sauropodomorph dinosaurs Plateosaurus and Massospondylus habitual quadrupeds. Special Papers in Palaeontology 77, 139-155.

Naish, D. 2017. Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths. Arcturus, London.

Senter, P. 2005. Function in the stunted forelimbs of Mononykus olecranus (Theropoda), a dinosaurian anteater. Paleobiology 31, 373-381.

Senter, P. 2006. Necks for sex: sexual selection as an explanation for sauropod dinosaur neck elongation. Journal of Zoology 271, 45-53.

Senter, P. 2007. A new look at the phylogeny of Coelurosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 5, 429-463.

Senter, P. 2009. Voices of the past: a review of Paleozoic and Mesozoic animal sounds. Historical Biology 20, 255-287.

Senter, P. 2017. Fire-breathing dinosaurs? Physics, fossils and functional morphology versus pseudoscience. Skeptical Inquirer 41 (4), 26-33.

Senter, P., Barsbold, R., Brtii, B. B. & Burnham, D. A. 2004. Systematics and evolution of Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda). Bulletin of the Gunma Museum of Natural History 8, 1-20.

Senter, P. & Parrish, J. M. 2005. Functional analysis of the hands of the theropod dinosaur Chirostenotes pergracilis: evidence for an unusual palaeoecological role. PaleoBios 25, 9-19.

Senter, P. & Robins, J. H. 2005. Range of motion in the forelimb of the theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, and implications for predatory behaviour. Journal of Zoology 266, 307-318.

Sullivan, R. M. & Williamson, T. E. 1999. A new skull of Parasaurolophus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus. New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science Bulletin 15, 1-52.

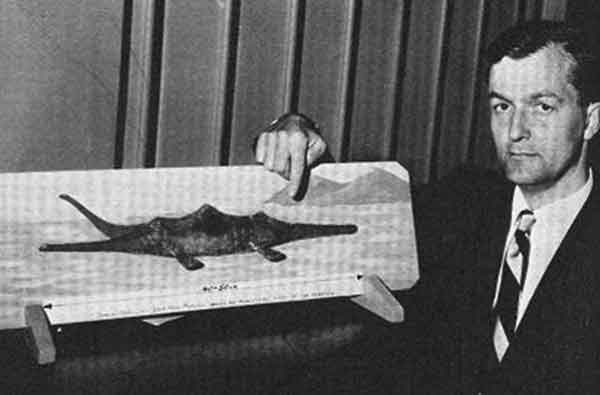

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 3: The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness

The story of the Loch Ness Monster is not a zoological one, no matter how desperately those who support the alleged existence of the monster wish it were. It is, instead, the story of people. Of people who tricked others into thinking that they saw or believed in a monster, of people who really thought they had seen a monster, and of people who wrote about, and theorised about, the thoughts, beliefs and adventures of others who’d thought or claimed they’d seen a monster.

Caption: Tim Dinsdale with his own reconstruction of the Loch Ness Monster (a clay model, held in place on a painted wooden board). I presume this photo was taken on the set of the BBC Panorama studio. Image: (c) Tim Dinsdale.

One of the most important characters as goes popularisation of the monster and promotion of its ostensible reality remains aeronautical engineer Tim Dinsdale (1924-1987). Over the three decades in which he was involved in the Loch Ness Monster story, he wrote four Nessie-themed books (Dinsdale 1961, 1966, 1973, 1975; not counting later editions), produced the text for a map (Dinsdale 1977), procured what remains the most famous piece of Nessie-based camera footage, and was deeply and closely involved in several campaigns and schemes to have the Loch Ness Monster formally recognised as a genuine animal species deserving legal protection.

Caption: covers of Dinsdale’s Loch Ness books - though not depicting all editions. Image: Darren Naish.

Those familiar with Dinsdale’s writings will already know the basics as goes his involvement in the Nessie saga. However, a lengthy work dedicated to his life and adventures was always needed, and I’m pleased to say that this gap in the literature was filled in 2013 by Angus Dinsdale’s The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness (A. Dinsdale 2013). This second Dinsdale is Tim Dinsdale’s son, who has written an affectionate but never overly sentimental review of his father’s life.

Caption: cover of A. Dinsdale’s 2013 book The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness.

My review here is the third and final part of the connected series on recently published books about the Loch Ness Monster (the other parts are here and here), though rest assured that it certainly won’t be the last thing I say on the subject since there are several other recently published works that warrant review as well (Ronald Binn’s 2019 The Decline of the Loch Ness Monster will likely be next). I appreciate that it might seem a bit odd to review a book published more than six years ago, but better late than never.

Caption: Dinsdale’s 1977 map is meant to be about Loch Ness in general. It is, of course, quite heavy on monster promotion (Dinsdale 1977). Image: Darren Naish.

The Man Who Filmed Nessie begins with several biographical chapters on Tim Dinsdale’s family background and early adult life. It is partly autobiographical, discussing the Dinsdale adventure as seen through the eyes of his son, but also includes long quoted sections from Dinsdale’s writings. In the text that follows, any mention of or reference to ‘Dinsdale’ should be assumed to refer to Tim Dinsdale, not Angus.

The story of how Dinsdale became seduced by the allure of the Loch Ness Monster is familiar to those who’ve read his books (Dinsdale 1961, 1975) and those written about him (e.g., Witchell 1975, Binns 1983, 2017, Campbell 1986, Williams 2015). For a level-headed person with a ‘practical’ background as an engineer, it’s remarkable how quickly Dinsdale became essentially convinced by the monster’s reality. This revelation wasn’t achieved after a personal encounter with the beast, nor after he’d spoken to some number of sincere witnesses. No: he read a single article in a popular magazine (Everybody’s magazine), titled ‘The Day I Saw the Loch Ness Monster’ (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 42).

Caption: Dinsdale’s identikit rendition of what the Loch Ness Monster must look like, reconstructed by taking averages from the various eyewitness encounters he’d read. Image: Dinsdale (1960).

Inspired and excited, he decided that he had to go to Scotland to see the beast for himself, so off he went. Aaaand… immediately saw Nessie! Yes, on the very first day of his arrival at Loch Ness (16th April 1960), Dinsdale thought that he’d seen Nessie. It turned out to be a floating tree trunk (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 51). On 21st April 1960 (the fourth day of his scheduled expedition at the loch) – shortly after spending time with water bailiff and Nessie oracle Alex Campbell – he again saw, and this time filmed, Nessie: “a churning ring of rough water, centring about what appeared to be two long black shadows, or shapes, rising and falling in the water!” (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 62). And on the final and sixth day of his expedition (23rd April 1960) he again saw and filmed Nessie, this time procuring the famous Foyers Bay footage, featuring a humped object – Dinsdale likened it to the “back of an African buffalo” – moving across the loch. After obtaining control footage of a boat (albeit at a different time of day, in different lighting conditions, and with a white-hulled boat obviously different from the mahogany ‘monster’), Dinsdale immediately messaged the British Museum, his reasoning being that the leading zoological institution of the country should hear about it first. After having the film developed, he waited, honestly expecting an excited cadre of professional biologists to beat a path to his door. After about seven weeks of silence, he gave up waiting and went to the press, his ultimately successful plan being to have the footage screened on the flagship BBC news programme Panorama.

Caption: a screengrab from the approximately 1 minute long Dinsdale film of April 1960. The dark object was thought by Dinsdale to be the mahogany brown, ‘peaked’ back of a massive aquatic animal. Image: (c) Tim Dinsdale.

He brought along a clay monster model he had made, the fact that it had been kitted out with three humps now appearing inconsistent with the monster shown in the footage. Alex Campbell also featured on the same TV show. To Dinsdale’s eyes, the Panorama experience was not merely crucial as goes the promotion of his case, but valuable in the scientific sense since the “increase in definition and contrast” made to the film by the TV people improved its clarity and shed additional information on the appearance of the Loch Ness animal.

Caption: a key character in the Loch Ness saga is water bailiff and journalist Alex Campbell. While at Fort Augustus, I got to see his waterside home, Inverawe. It’s the building at far right here. Dinsdale spent time with Campbell immediately before seeing and filming his ‘monster’ of April 1960. Image: Darren Naish.

Our view of Dinsdale’s film today is that it isn’t impressive and almost certainly doesn’t depict a monster. There were surely viewers at the time who must have been equally unimpressed and Dinsdale’s view that the scientists and specialists who viewed the film in secrecy displayed nothing but apathy (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 73) is, of course, a biased take since he simply expected them to agree with his interpretation. The object he filmed was no giant unknown aquatic animal, but a boat (Binns 1983, Campbell 1986, Harmsworth 2010, Naish 2017; and see Dick Raynor’s page on the footage here).

Caption: Loch Ness is often a beautiful and serene body of water, but I can’t help feeling that it must seem remote and lonely at times of the year. This photo was taken in the Spring of 2016. Image: Darren Naish.

Prior to reading this book, my feelings about Tim Dinsdale were tempered by the fact that I thought him odd for abandoning his family for long stretches while engaging in the esoteric pursuit of an alleged mystery beast in a part of the country far from home. Furthermore, my idiosyncrasies mean that I’m automatically jealous or resentful of anyone who gets to engage in an expensive hobby at what appears to be infinite leisure.

Caption: few people seriously interested in the Loch Ness Monster can claim to have spent as much time on, or close to, the waters of the loch as Dinsdale did. But many people familiar with Dinsdale’s writings have sought to follow his footsteps, at least in part. Image: Darren Naish.

It turns out that none of these things are true. Dinsdale’s monster-hunting came at great personal expense and involved some degree of hardship. Furthermore, he deliberately included his family in his monster-hunting expeditions. I particularly liked Angus’s description of the childhood tradition in which he would procure the largest available carrot from the supermarket; this was to accompany his father on an expedition, the plan being that it would be fed to Nessie once she and Angus’s dad had made friends (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 86). Whatever Dinsdale’s legacy, the lives of his children were surely enriched by their regular trips to Scotland and their involvement in something as unusual as the pursuit of the Loch Ness Monster, though I have to admit that my personal circumstances while reading this book – I was working in China and missing my family – probably influenced my sentimental feelings on this issue.

Caption: you’ve probably read that the water of Loch Ness is tea-coloured. This is what it looks like when the bottom is less than 1 m away. Get to a depth of 10 m, and there’s essentially no light and nothing but darkness - at least, as far as the human eye is concerned. Image: Darren Naish.

While monster hunting, Dinsdale occasionally checked the shoreline. He was aware of the land sightings of Nessie and kept in mind the possibility that he might see the beast on land himself. I should mention here that refractory Nessie fan and blogger Roland Watson has recently published an entire book on the subject of land sightings, titled When Monsters Come Ashore. It’s written in extremely large font and in the bombastic and childish style characteristic of True Believers and is surely not a fair continuation of the level-headed and restrained, respectful tone of Dinsdale’s writings. In other words, poor Tim would not be happy with the state of Nessie promotion occurring among those few who might consider themselves his modern disciples.

One of the most interesting sections of the Nessie story concerns the arrival of the Americans and the use of assorted high-end bits of mechanical and photographic kit. While it might have seemed that Dinsdale and other British Nessie-hunters could have been gradually edged out of the quest, Robert Rines and his colleagues were on good terms with Dinsdale and even helped win him a lecture tour of the US, and ultimately to appear on big-hitting TV shows like The David Frost Show and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (A. Dinsdale 2013).

Caption: a Loch Ness scene, fortuitously featuring a waterbird (in this case, a Mute swan Cygnus olor) and a boat. Both objects have undoubtedly contributed in no small part to the phenomenon known as the Loch Ness Monster. Image: Darren Naish.

Indeed, Dinsdale’s fame reached its peak during the early and mid 1970s, as did the quest for Nessie in general. The mounting excitement that something was surely there and due to be confirmed – a belief fuelled by all that fancy American technology – inspired the idea that Nessie-like animals might lurk in other, nearby bodies of water. The book recounts Dinsdale’s expedition to Loch Morar, a place very different from Loch Ness but also said to have its own monster, called Morag. The main point of interest here to monster nerds is that the Dinsdales happen to meet a Mrs Parks, sister to one of two men who claimed a close Morag encounter.

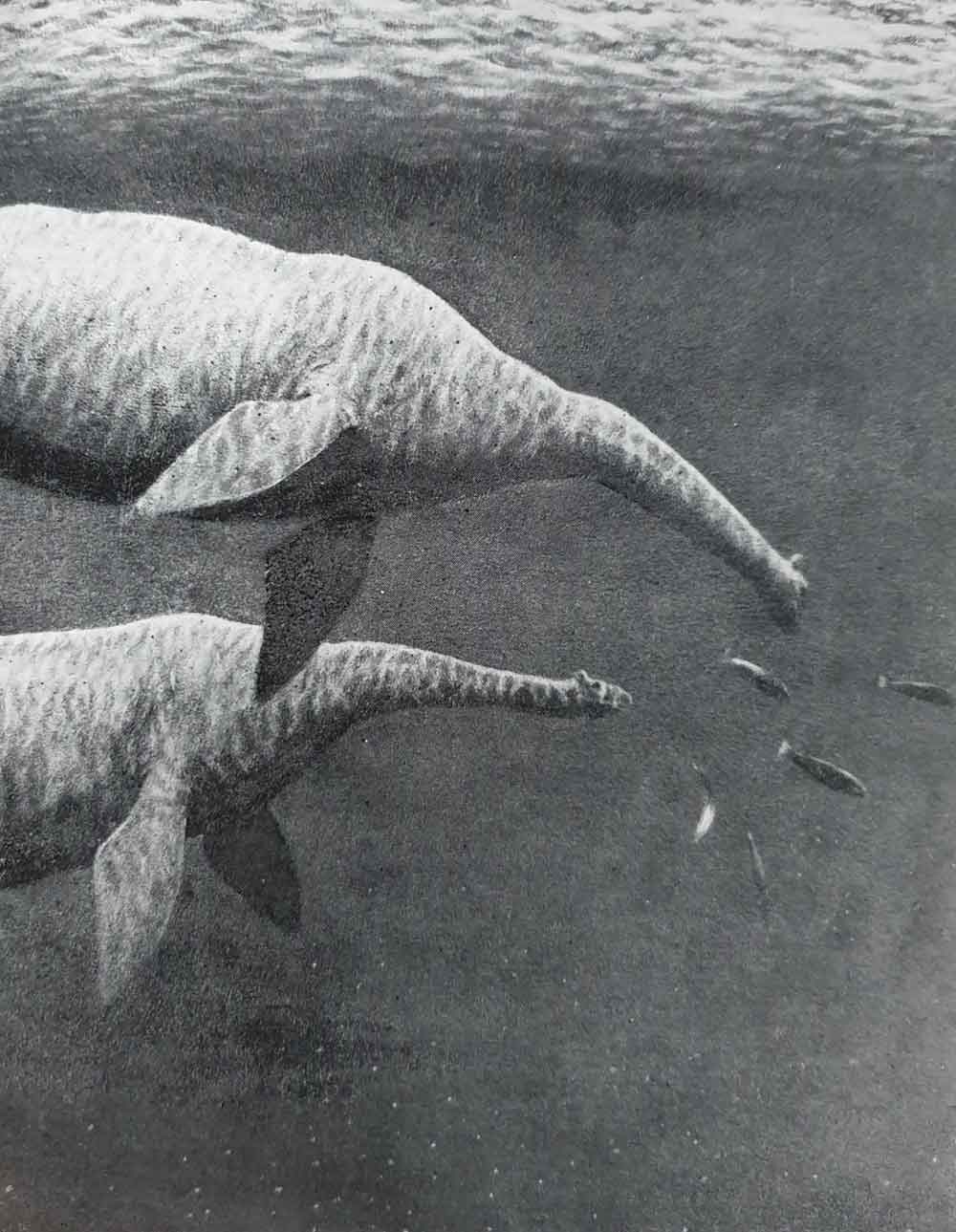

Caption: Dinsdale was never explicit about the zoological identity he favoured for the Loch Ness Monster, but he clearly favoured the idea that it was a living plesiosaur, albeit one that had undergone a fair amount of change since the end of the Cretaceous. The legend of the late-surviving plesiosaur - reflected in this model, made for a TV show and photographed at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History in 2005 - owes something to Dinsdale’s writing. Image: Darren Naish.

The story – recounted in several monster books – is famous because the two men (Duncan McDonell and William Simpson) apparently had to use an oar to fend Morag away from their boat, and so vigorous was the interaction that the oar snapped. The story usually ends there. Another Nessie-themed book, however, explains how the individuals concerned had been poaching deer and were trying to discard an unwanted skin which, despite being filled with stones, refused to sink. Eventually it had to be whacked with an oar, and here we find what is claimed to be the actual explanation for the oar-breaking event (Harmsworth 2010, p. 218).

Caption: the ‘two people in a lake come so close to a monster that they have to hit it with an oar’ trope has been taken seriously enough to inspire this re-enactment, this time involving the Lake Storsjö monster of Sweden. The man with the oar is Ragner Björks. Image: Bord & Bord (1980).

In places, Dinsdale’s story arc is a melancholy one. He wrote of his realisation, years after his initial forays in boats on Loch Ness, that he had become an experienced and confident boatman, his long, quiet stretches involving grey water, and rain. He never was to experience anything again as thrilling as his 1960 filming of the ‘monster’s hump’, nor did this footage receive the accolade he hoped it would. The decline and demise of the Loch Ness Investigation Bureau during the early 1970s marked “the end of an era” (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 200), and even the 1975 scientific symposium – the high water mark of Nessie’s scientific respectability, convened to discuss the sonar traces and photos obtained by Rines and his colleagues – was regarded as a disappointment (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 217). As scientific interest in Nessie waned during the 1980s, Dinsdale complained in 1987 that scepticism had taken over, that “Nessie in the 80s has, if anything, been going backwards” (Williams 2015, p. 202). A planned sequel to 1975’s Project Water Horse, intriguingly titled Loch Ness and the Water Unicorn, and said in the 1982 edition of Loch Ness Monster to be partly written, never appeared in print (Binns 2019).

Caption: scientific interest in Nessie might have waned during the 1980s, but this was the decade that gave us this fantastic book cover. You might doubt that encounters as close and thrilling as this ever occurred. It belongs to the sixth edition of this book, published in 1982.

Some authors, especially those championing the Loch Ness Monster’s existence, have framed Tim Dinsdale as the most brilliant, wise and relevant authority on the Loch Ness Monster (pro-Nessie author Henry Bauer is an example). It’s easy to be convinced from Dinsdale’s writings, and his son’s, that he was indeed sincere, honest, and trying as best he might to stir scientific and mainstream interest in something that he regarded as unquestionably real. And his underlying methodology was scientific. But he seemed never to grasp why the official response was one of apparent disinterest and apathy. It wasn’t down to “stubbornness … indifference … [and] arrogance” (A. Dinsdale 2013, p. 232), but to the fact that the evidence just wasn’t good enough, and that there never was a good reason to believe in a monster. That Dinsdale became almost fixated on the monster’s existence after reading a single popular magazine article does not – I have to say it, forgive me – seem consistent with someone who might be deemed wise, level-headed and of the most sceptical, rational approach.

Caption: the Peter O’Connor photo of 1960 - this is a low-res, cropped version - has appeared several times at TetZoo over the years and is almost certainly a hoax, most likely an overturned kayak and a model head and neck (Naish 2017). Dinsdale included it in early editions of his book Loch Ness Monster but it - and any accompanying prose devoted by Mr O’Connor - is absent from the fourth edition and those that appeared afterwards. Image (c) Peter O’Connor.

On that note, and while it again shames me to say it, I’m impressed – if that’s the right word – by Dinsdale’s naivety when we look at specific parts of his Loch Ness experience. Take his interaction with Tony Shiels, the self-proclaimed Wizard of the Western World. In 1977 Shiels claimed to capture on film the most remarkable colour photos of Nessie ever taken, an object affectionately known today as the Loch Ness Muppet. Any familiarity with Shiels and his adventures quickly reveals that he has, and seemingly always has had, a tongue-in-cheek, jovial take on monsters and how they might be seen. They’re not really meant to be undiscovered animals lurking in remote places, but interactive pieces of quasi-surreal art akin to open-air theatre, the ensuing cultural response in literature and news being as much a part of the event, if not more, as the claimed sighting and photo. While I undoubtedly write with the benefit of hindsight (and, dare I say it, some quantity of insider information), Dinsdale was seemingly unable to perceive this. And thus the muppet photo appears – as a legit image of the Loch Ness animal – on the cover of the fourth edition of Dinsdale’s The Loch Ness Monster, a decision that speaks volumes.

Caption: the infamous 1977 Shiels muppet photo. Exactly what it depicts (a plasticine model superimposed on a scene showing water? A floating model posed in the loch?) remains uncertain. Image: (c) Tony Shiels.

The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness is an essential read for those seriously interested in the history of monster searching and the people who engage in it. The book has very high production values and impressive design and editorial standards, and includes an excellent colour plate section. I enjoyed reading it and think that Angus Dinsdale has produced a book that his late father would have been proud of, and moved by. Many interesting people have contributed to the lore of the Loch Ness Monster, and Dinsdale was without doubt one of the most important and influential. I leave you to judge whether this was time wasted, or a life enriched and made remarkable.

Dinsdale, A. 2013. The Man Who Filmed Nessie: Tim Dinsdale and the Enigma of Loch Ness. Hancock House, Surrey, BC Canada. pp. 256. ISBN 978-0-88839-727-0. Softback, refs, index. Here at amazon. Here at amazon.co.uk.

Nessie and related issues have been covered on TetZoo a fair bit before, though many of the older images now lack ALL of the many images they originally included…

The Loch Ness monster seen on land, October 2009 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Dear Telegraph: no, I did not say that about the Loch Ness monster, July 2011 (now missing all images due to hosting issues)

Photos of the Loch Ness Monster, revisited, July 2013 (now stripped of all images, so completely useless)

Is Cryptozoology Good or Bad for Science? (review of Loxton & Prothero 2013), September 2014 (now stripped of all images)

My New Book Hunting Monsters: Cryptozoology and the Reality Behind the Myths, February 2016

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 1: Ronald Binns’s The Loch Ness Mystery Reloaded, March 2019

Books on the Loch Ness Monster 2: Gareth Williams’s A Monstrous Commotion, March 2019

Refs - -